Published online Feb 28, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.115654

Revised: December 11, 2025

Accepted: December 31, 2025

Published online: February 28, 2026

Processing time: 112 Days and 21.3 Hours

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease involving multiple organ systems. Lupus enteritis is a rare but potentially life-threatening gastrointestinal manifestation characterized by immune complex-mediated in

A 47-year-old female with a known history of SLE and membranous glomerulonephritis presented with acute epigastric pain. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed venous-type ischemia involving the second portion of the duodenum and proximal jejunum. Despite intensive medical management, pro

Prompt recognition and multidisciplinary management are essential for favorable outcomes in patients with severe lupus enteritis and duodenal involvement.

Core Tip: Duodenal involvement in lupus enteritis is exceptionally rare and may progress to ischemia requiring surgery. Early recognition is critical, as delayed diagnosis can be life-threatening. Because it is often difficult to predict whether lupus enteritis will respond to steroids or instead progress to ischemia, a multidisciplinary approach and timely decision-making are essential. In this case, early duodenal resection and duodenojejunostomy prevented further deterioration, and post

- Citation: Kim YK, Jung HI, Kim H, Bae SH. Ischemic duodenal injury due to systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(8): 115654

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i8/115654.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.115654

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disorder that can affect virtually any organ system, including the nervous system, skin, joints, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointestinal symptoms occur in up to 50% of patients with SLE, but are most often related to medications or infection rather than lupus enteritis itself[1]. Lupus enteritis is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication, characterized by immune complex vasculitis and complement activation within mesenteric vessels leading to submucosal edema, hemorrhage, or ischemic necrosis[2,3].

Failure to recognize or treat this condition promptly can result in bowel infarction or perforation. We present a rare case of duodenal lupus enteritis complicated by ischemic necrosis that required surgical resection, followed by post

The patient began to experience epigastric pain the previous day.

A 47-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with sudden worsening epigastric pain that began the previous day and was squeezing in nature. She did not experience nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea.

Her past medical history included SLE and membranous glomerulonephritis diagnosed five years earlier at another hospital; at that time, she had presented with photosensitive cutaneous eruptions. She had not received immunosuppressive therapy since diagnosis and had been managing intermittent skin symptoms only with antihistamines and moi

She reported no prior abdominal surgery and no family history of autoimmune or gastrointestinal disease.

On physical examination, marked epigastric tenderness was observed without rebound tenderness or rigidity. No malar or discoid rash was present, but urticarial facial lesions, subconjunctival hemorrhage, palpable purpura on both hands, and petechiae on both lower legs were observed, suggesting active vasculitic involvement (Figure 1).

Initial laboratory values were: White blood cell was 7600/μL (normal 4000-10000/μL), C-reactive protein (CRP) was 1.41 mg/dL (normal < 0.5 mg/dL), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 51 mm/hour (normal < 20 mm/hour), fibrin degradation product (FDP) was 17.96 μg/mL (normal 0-2.0 μg/mL), and D-dimer was 5.35 μg/mL (normal 0-0.48 μg/mL). Complement levels were low, with C3 at 52 mg/dL (normal 90-180 mg/dL) and C4 at 7.08 mg/dL (normal 10-40 mg/dL). Anti-dsDNA IgG was negative (0.7 IU/mL; normal < 10 IU/mL). Urinalysis demonstrated marked proteinuria (+4, approximately 1000 mg/dL) and microscopic hematuria [10-19 red blood cells per high-power field (RBC/HPF)]. Taken together, these findings yielded a Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI)-2000 score of 18 points (vasculitis +8, proteinuria +4, hematuria +4, low complement +2), indicating high disease activity. Elevated ESR and SLEDAI with relatively normal CRP suggested active lupus inflammation rather than infection, while markedly increased FDP and D-dimer implied ongoing microthrombus formation due to vasculitis[4,5]. Given these findings and the computed tomography (CT) features of non-occlusive ischemia, the rheumatology team considered lupus enteritis as the primary diagnosis.

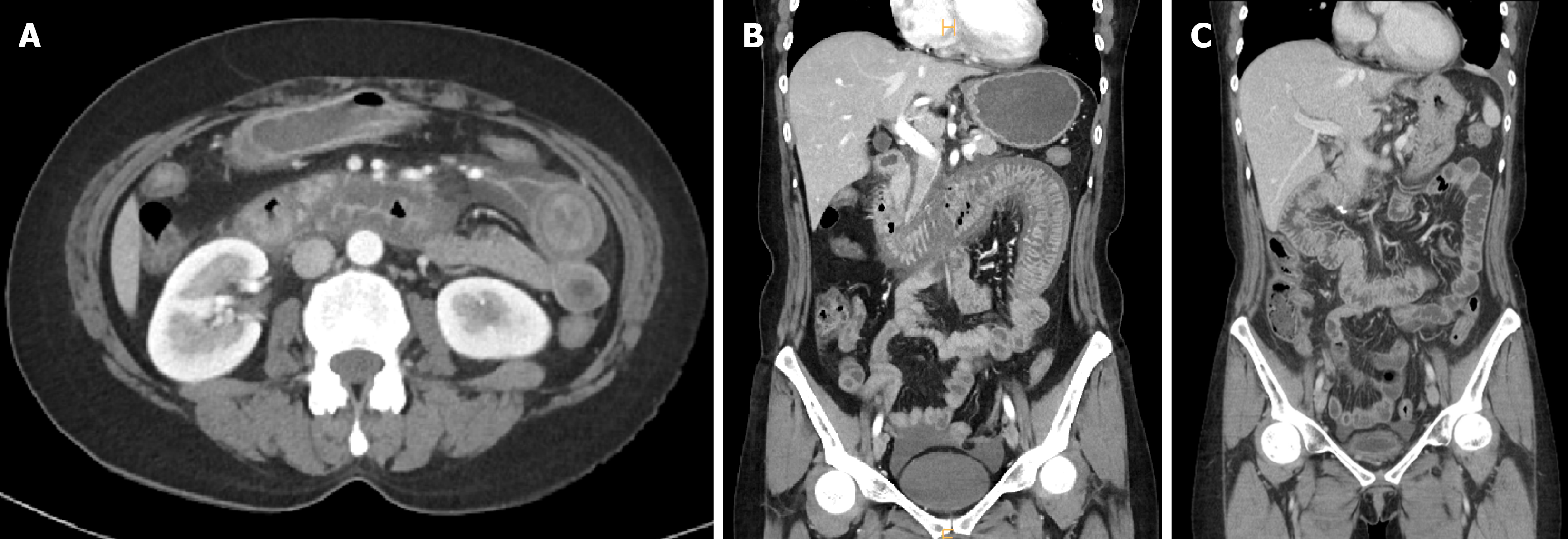

Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT demonstrated circumferential wall thickening and mucosal hyperenhancement involving approximately 50 cm of small bowel from the second portion of the duodenum to the proximal jejunum, with surrounding mesenteric fluid and engorged mesenteric veins (Figure 2A and B).

No occlusive lesion was detected in the superior mesenteric artery or vein, suggesting venous ischemia rather than arterial obstruction. These findings are consistent with previously described radiologic features of lupus enteritis, where venous congestion and submucosal edema predominate[6-8].

Considering the patient’s acute deterioration and radiological evidence of bowel ischemia, the surgical team carefully balanced conservative steroid therapy with exploratory laparotomy. Corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may obscure peritoneal signs and delay the detection of necrosis; conversely, delayed surgery increases the risk of transmural infarction and sepsis. Assessment of bowel viability in lupus enteritis is challenging because reperfusion may transiently restore color despite persistent microvascular occlusion[9]. Considering the rapid progression of pain and high SLEDAI scores, exploratory laparotomy was performed to evaluate the irreversible ischemic injury.

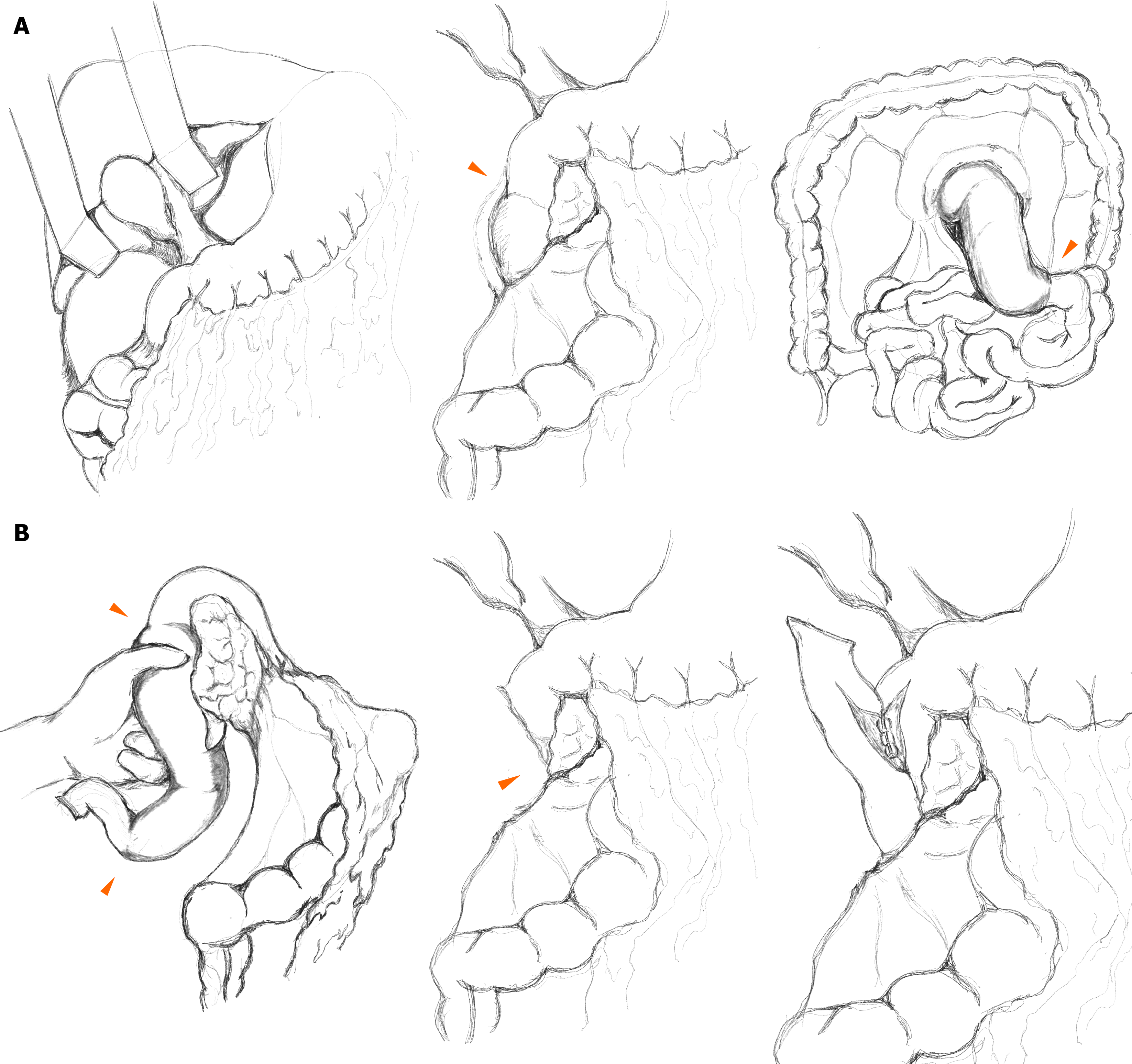

Exploration revealed segmental edema and induration from the second portion of the duodenum to the proximal jejunum. The bowel was pink, but thickened and firm, consistent with venous infarction rather than arterial occlusion. Mesenteric fat was edematous with lymphatic-like fluid extending retroperitoneally along the Toldt fascia. After the Kocher maneuver and right colon mobilization, distal transection was performed at the proximal jejunum using a linear stapler (TLC 55-mm stapler, Covidien®) at the point where the edema subsided. The mesentery was divided using an energy device. The resected jejunal limb was passed posterior to the superior mesenteric vessels and careful dissection was performed near the pancreatic uncinate process to preserve the ampulla of Vater. Proximal transection of the second portion of the duodenum was performed diagonally using a stapler (TLC 75-mm stapler, Covidien®), sparing a small edematous segment to avoid ampullary injury. A side-to-side duodenojejunostomy was performed with vertical incisions and hand-sewn closures (full-thickness continuous sutures with PDS 4-0, Ethicon®; and seromuscular continuous Lambert sutures with Pronova 5-0, Ethicon®; Figure 3).

Grossly, the resected specimen showed transmural edema and localized mucosal hemorrhage without perforation (Figure 4). Histopathological examination later confirmed ischemic necrosis with small-vessel vasculitis and fibrinoid necrosis, which are typical of lupus enteritis[8,10].

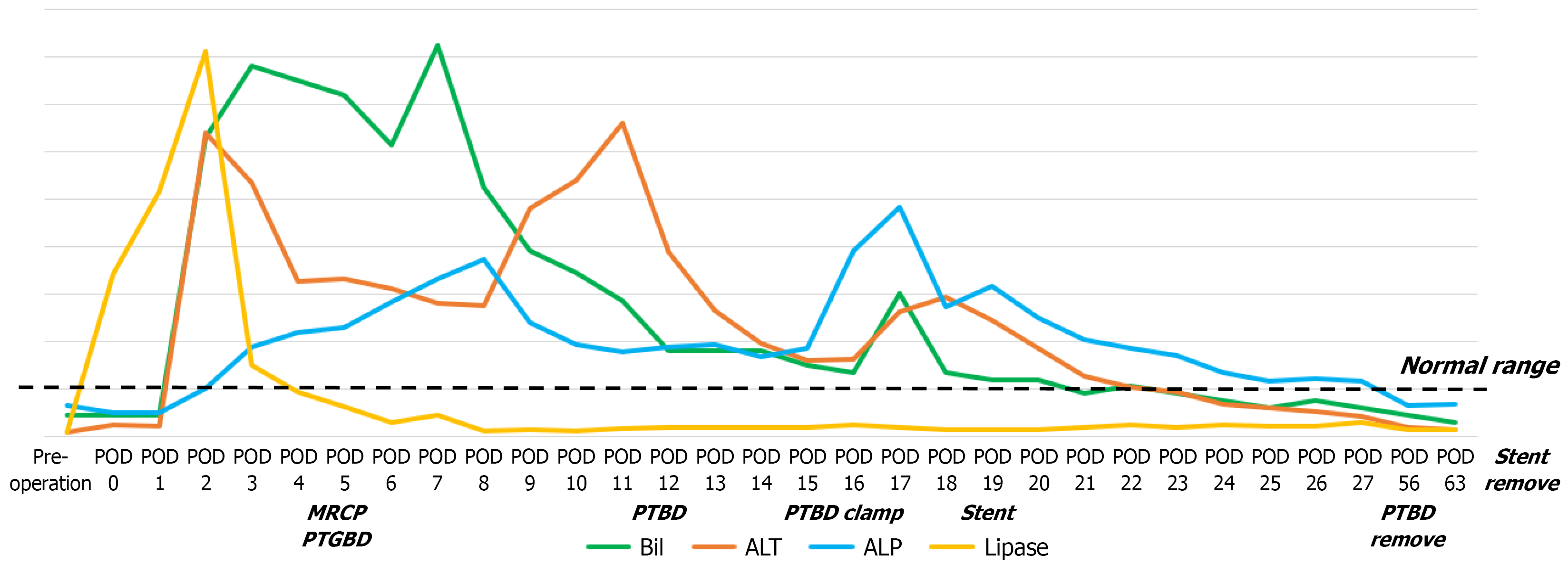

High-dose intravenous hydrocortisone (100 mg every 12 hours) was initiated on postoperative day (POD) 2, and continued for 6 days until POD 7. The regimen was transitioned to oral methylprednisolone on POD 8 (10 mg twice daily). No additional immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, or rituximab were admi

On POD 1, the serum amylase and lipase levels rose, indicating mild pancreatitis. On POD 2, total and direct bilirubin levels also rose, suggesting possible ampullary edema or obstruction caused by postoperative inflammation. On POD 3, pancreatic enzyme levels began to normalize; however, bilirubin and liver function test results continued to worsen. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography on POD 5 revealed dilation of both the common bile duct and pancreatic duct, while the ampulla of Vater could not be clearly identified because of the stapling line near the duodenojejunal anastomosis.

Initial biliary decompression was accomplished via percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) because the peripheral ducts were too narrow for direct percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) access. On POD 12, the PTGBD catheter was converted to a PTBD by advancing the tube through the cystic duct. Gastroduodenoscopy on POD 14 revealed persistent mucosal edema obscuring the ampulla and precluding endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-guided stenting. Between PODs 14 and 18, PTBD clamping provoked recurrent epigastric pain, vasculitic skin rash, and subconjunctival hemorrhage, which are findings consistent with an SLE flare triggered by cholestasis. During this period, the dose of oral methylprednisolone was temporarily increased to 20 mg twice daily. On POD 19, a metallic stent was successfully deployed through the PTBD tract across the ampulla and duodenojejunal anastomosis to restore bile flow. Laboratory indices normalized thereafter, and the patient was discharged on POD 30 with both the PTBD catheter and the internal stent remaining in place.

During outpatient follow-up, the internal biliary stent was removed endoscopically approximately 6 months postoperatively. Immediate cholangiography performed through the existing PTBD tract confirmed smooth bile drainage without residual obstruction. The PTBD catheter was removed shortly thereafter without complications. Under rheumatologic su

At the 1-year follow-up, laboratory evaluation demonstrated normalized inflammatory markers (ESR = 15 mm/hour; normal < 20 mm/hour), negative anti-dsDNA IgG, and improved complement levels (C3 = 65.4 mg/dL, normal 90-180 mg/dL; C4 = 12.1 mg/dL, normal 10-40 mg/dL). Urinalysis showed only trace proteinuria (10 mg/dL) without hema

Lupus enteritis results from immune complex-mediated vasculitis of the mesenteric vessels, leading to bowel wall edema, venous congestion, and occasionally, ischemic necrosis[2,3]. Duodenal involvement is extremely rare, likely because the proximal intestine has rich collateral circulation from the pancreaticoduodenal arcade[10,11]. Despite its rarity, the cli

Radiologically, lupus enteritis typically shows the “target sign” (concentric mural enhancement due to submucosal edema) and the “comb sign” (engorged mesenteric vessels)[7,10]. However, in severely ischemic forms, mucosal en

Rheumatological parameters such as elevated SLEDAI, high anti-dsDNA titers, and hypocomplementemia are often associated with lupus enteritis activity[4]. The patient’s high SLEDAI score (18) and elevated FDP/D-dimer levels in

Surgical management is generally reserved for irreversible complications such as perforation or bowel infarction, as delayed intervention increases mortality in lupus enteritis[18]. In this patient, ischemia progressed despite high-dose corticosteroids and further delay would have increased the extent of necrosis and more complex reconstruction; therefore, early surgery was performed. Recent comparative data suggest that E-style (end-to-end) duodenojejunostomy may decrease delayed gastric emptying and intraperitoneal infection compared to S-style (side-to-side) configurations[19]. However, in our case, the ischemic segment extended along the second posterior portion of the duodenum near the ampulla of Vater. To avoid pancreaticoduodenectomy, our priority was to preserve the ampullary region, even if a small portion of the marginally perfused duodenum remained. Diagonal proximal transection was performed to maximally remove the devitalized segment, as illustrated in the operative schema (Figure 3B). Areas of edematous and poorly perfused tissue were left as short stapled stumps, and a hand-sewn side-to-side duodenojejunostomy was chosen because it allowed tension-free anastomosis of well-vascularized tissue and represented the most anatomically feasible configuration.

From a pathological perspective, histopathological examination in this case revealed small-vessel vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis and luminal thrombosis, confirming ischemic injury secondary to lupus activity rather than an atherosclerotic or embolic etiology[2,20]. The presence of transmural necrosis with fibrinoid vascular injury and immune com

The postoperative pancreatitis and biliary obstruction in this patient can be explained by several plausible mechanisms. First, duodenal resection adjacent to the ampulla of Vater may induce reactive edema, resulting in transient mechanical obstruction of pancreaticobiliary outflow. Second, ischemic injury from mesenteric vasculitis may impair papillary function even if the ampulla is anatomically preserved. Finally, lupus-related microvascular inflammation may involve the pancreaticobiliary ducts and contribute to functional obstruction. Prompt radiological evaluation and timely drainage are essential because cholestasis can precipitate SLE exacerbation through inflammatory cytokine release[23].

This case highlights the need for a multidisciplinary approach. Radiologists play a key role in distinguishing between ischemic and inflammatory patterns; rheumatologists direct the intensity of immunosuppressive therapy; pathologists confirm vasculitic injury; and surgeons intervene when irreversible ischemia develops. Early recognition of duodenal involvement, appropriate immunotherapy, and vigilant postoperative monitoring of biliary complications are critical for achieving favorable outcomes. The patient reported marked relief of abdominal symptoms and expressed satisfaction with her recovery and the overall treatment process.

Severe lupus enteritis with duodenal ischemic necrosis is rare. The combination of radiologic venous ischemia, histologic vasculitis, and SLE flares supported an autoimmune etiology. Although corticosteroids remain the cornerstone of therapy, clinicians should be vigilant for ischemic transformation requiring surgical intervention. Close multidisciplinary collaboration and meticulous postoperative management of biliary complications are essential for long-term recovery.

The authors thank the Departments of Rheumatology, Departments of Radiology, and Departments of Pathology at the Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital for their valuable collaboration in the diagnosis and management of this case.

| 1. | Alharbi S. Gastrointestinal Manifestations in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Open Access Rheumatol. 2022;14:243-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Amouei M, Momtazmanesh S, Kavosi H, Davarpanah AH, Shirkhoda A, Radmard AR. Imaging of intestinal vasculitis focusing on MR and CT enterography: a two-way street between radiologic findings and clinical data. Insights Imaging. 2022;13:143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chen L, He Q, Luo M, Gou Y, Jiang D, Zheng X, Yan G, He F. Clinical features of lupus enteritis: a single-center retrospective study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:448-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4404] [Cited by in RCA: 4715] [Article Influence: 174.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Cui M, Wang Q, Xin AW, Che D, Lu Z, Zhou L, Xin W. Vascular thrombosis and vasculitis in the gastrointestinal tract are associated with poor prognosis in patients with COVID-19. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2021;14:1069-1079. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Smith LW, Petri M. Lupus enteritis: an uncommon manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19:84-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Muñoz-Urbano M, Sanchez-Bautista J, Ramírez A, Santamaría-Alza Y, Quintero-González DC, Vanegas-García AL, Vásquez G, González LA. Lupus enteritis: A 10-year experience in a single Latin American center. Lupus. 2023;32:910-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Janssens P, Arnaud L, Galicier L, Mathian A, Hie M, Sene D, Haroche J, Veyssier-Belot C, Huynh-Charlier I, Grenier PA, Piette JC, Amoura Z. Lupus enteritis: from clinical findings to therapeutic management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brandt LJ, Boley SJ. AGA technical review on intestinal ischemia. American Gastrointestinal Association. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:954-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tian XP, Zhang X. Gastrointestinal involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: insight into pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2971-2977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Triantafyllou G, Lyros O, Arkadopoulos N, Kokoropoulos P, Demetriou F, Samolis A, Olewnik Ł, Landfald IC, Piagkou M. The Blood Supply of the Human Pancreas: Anatomical and Surgical Considerations. J Clin Med. 2025;14:5625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M, Amoura Z, Cervera R, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Cuadrado MJ, Dörner T, Ferrer-Oliveras R, Hambly K, Khamashta MA, King J, Marchiori F, Meroni PL, Mosca M, Pengo V, Raio L, Ruiz-Irastorza G, Shoenfeld Y, Stojanovich L, Svenungsson E, Wahl D, Tincani A, Ward MM. EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1296-1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 785] [Cited by in RCA: 796] [Article Influence: 113.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wiesner W, Khurana B, Ji H, Ros PR. CT of acute bowel ischemia. Radiology. 2003;226:635-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kenar G, Atay K, Yüksek GE, Öz B, Koca SS. Gastrointestinal vasculitis due to systemic lupus erythematosus treated with rituximab: a case report. Lupus. 2020;29:640-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gan H, Wang F, Gan Y, Wen L. Rare case of lupus enteritis presenting as colorectum involvement: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:8176-8183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Williamson L, Hao Y, Basnayake C, Oon S, Nikpour M. Systematic review of treatments for the gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2024;69:152567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Andersen J, Aringer M, Arnaud L, Bae SC, Boletis J, Bruce IN, Cervera R, Doria A, Dörner T, Furie RA, Gladman DD, Houssiau FA, Inês LS, Jayne D, Kouloumas M, Kovács L, Mok CC, Morand EF, Moroni G, Mosca M, Mucke J, Mukhtyar CB, Nagy G, Navarra S, Parodis I, Pego-Reigosa JM, Petri M, Pons-Estel BA, Schneider M, Smolen JS, Svenungsson E, Tanaka Y, Tektonidou MG, Teng YO, Tincani A, Vital EM, van Vollenhoven RF, Wincup C, Bertsias G, Boumpas DT. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus: 2023 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83:15-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 586] [Article Influence: 293.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lin HP, Wang YM, Huo AP. Severe, recurrent lupus enteritis as the initial and only presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in a middle-aged woman. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2011;44:152-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liu W, Wang J, Ma L, Zhuang A, Xu J, He J, Yang H, Fang Y, Lu W, Zhang Y, Tong H. Which style of duodenojejunostomy is better after resection of distal duodenum. BMC Surg. 2022;22:409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sultan SM, Ioannou Y, Isenberg DA. A review of gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38:917-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Leone P, Prete M, Malerba E, Bray A, Susca N, Ingravallo G, Racanelli V. Lupus Vasculitis: An Overview. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tsokos GC, Lo MS, Costa Reis P, Sullivan KE. New insights into the immunopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:716-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 587] [Cited by in RCA: 906] [Article Influence: 100.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ohl K, Tenbrock K. Inflammatory cytokines in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:432595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/