Published online Feb 28, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.115675

Revised: December 13, 2025

Accepted: January 4, 2026

Published online: February 28, 2026

Processing time: 112 Days and 7 Hours

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer and ranks as the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are predomi

Core Tip: As a predominant population of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) play an important role in the initiation and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). TAM-derived factors, including but not limited to cytokines, chemokines, and exosomes, regulate angiogenesis, immunosuppression, and therapeutic resistance in HCC. Strategies such as reprogramming TAM polarization, suppressing immunosuppressive cell recruitment, and inhibiting immunosuppressive signaling pathways can decrease tumor-promoting immune cell recruitment, reinforce the cytotoxicity of T cells, and retard tumor cell proliferation, ultimately slowing or delaying tumor growth.

- Citation: Yang M, Zhang CY. Molecular mechanisms of tumor-associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma development and therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(8): 115675

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i8/115675.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.115675

Globally, about 905700 people were diagnosed with liver cancer, and 830200 people died from it in 2020[1]. The number of new liver cancer cases is predicted to increase to 1.4 million in 2040, resulting in an estimated 1.3 million deaths[1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for 80%-90% of primary liver cancers. The epidemiology of HCC is changing due to the increasing prevalence of obesity and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), alcoholic consumption, and improved treatments of hepatitis virus-induced HCC[2,3].

Surgical ablation is a curative therapy for early-stage HCC. However, most HCC cases are diagnosed at the later stages, which are not suitable for surgical intervention or ablation[4,5]. The approval of immunotherapies, such as nivolumab [an anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) antibody], durvalumab [an anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody], and ipilimumab (an anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 antibody), offers a promising approach to extend the survival of HCC patients. Nonetheless, the benefits of immune checkpoint inhibitors, whether used alone or in combination, remain limited due to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME)[6].

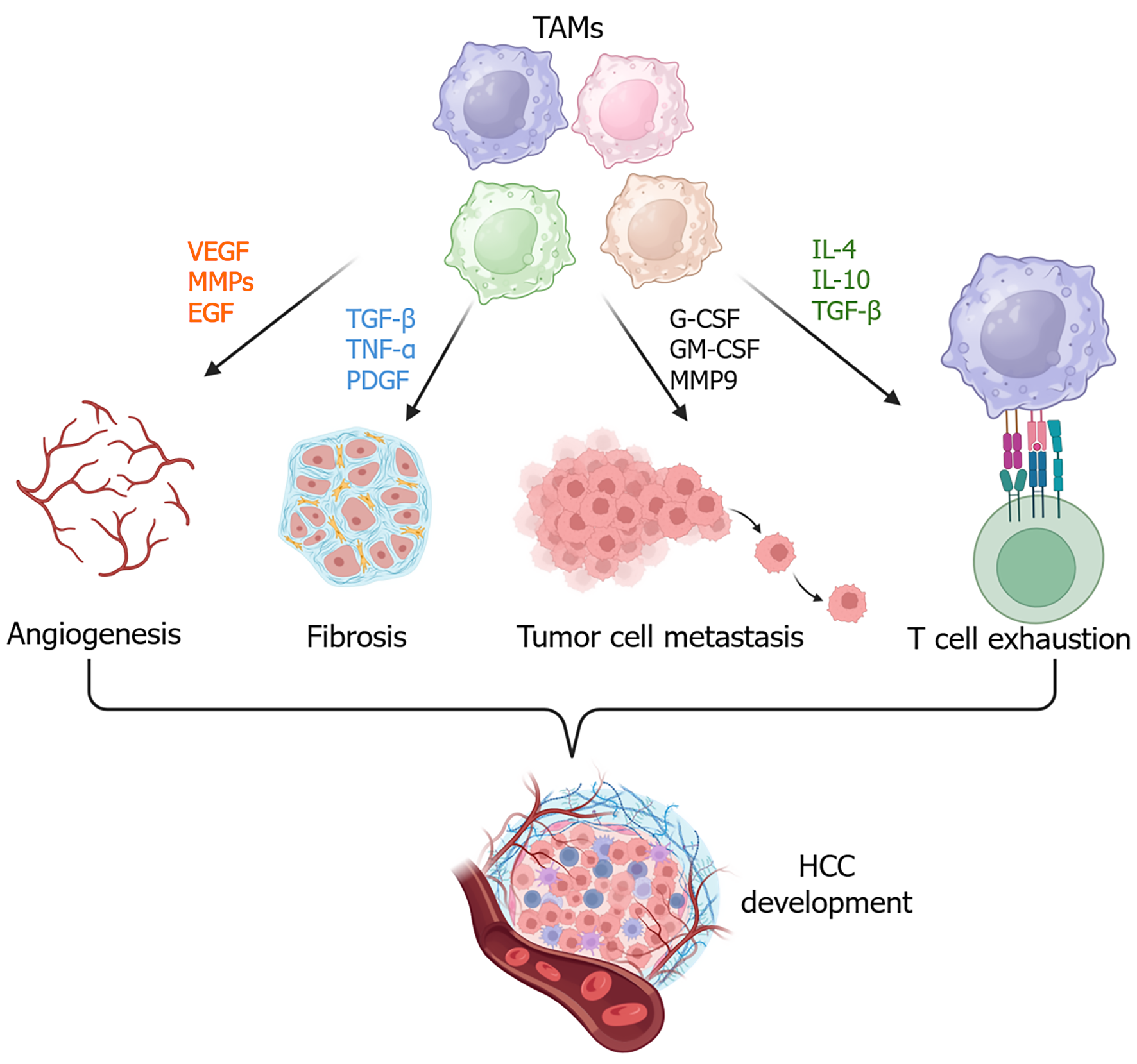

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are predominant immune cells in the TME of HCC[7,8], playing a pivotal role in the initiation and progression of HCC. TAMs can secrete various cytokines and chemokines, which contribute to an immunosuppressive TME by increasing myeloid cell infiltration, promoting fibrosis, and facilitating angiogenesis[9], and enhancing the attraction, differentiation, or proliferation of regulatory T cells (Tregs)[10,11]. Additionally, TAMs can promote HCC cell invasion and stemness[12-14].

Modulation of TAMs can improve the therapeutic efficacy of HCC treatments. For example, Cheng et al[15] reported that short-term starvation enhanced the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 in HCC[15]. Cellular and molecular studies revealed that reshaping TAMs from a pro-tumoral phenotype to an anti-tumoral phenotype improved macrophage phagocytic activity against tumor cells by regulating the fructose diphosphatase 1, decreasing exosomal PD-L1 expression, and increasing cluster of differentiation (CD) 8+ T cell cytotoxicity as evidenced by increased production of granzyme B and interferon (IFN)-γ[15].

In this review, we discuss the origins and functions of TAMs, as well as the molecular signaling pathways involved in HCC development and progression. We also summarize potential therapeutic strategies targeting TAMs for HCC treatment.

The population of TAMs is closely associated with the initiation and progression of HCC. TAM-like macrophages can also present during the chronic liver disease stage. In metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) livers, TAM-like macrophages have been found to be associated with the exhaustion of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells[16], which can promote HCC development. During the development and progression of HCC, chemokines/chemokine receptors axes regulate the infiltration of macrophages in the TME. The upregulation of C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) in HCC cells attracts macrophages expressing C-C motif chemokine receptor (CCR) 2 to infiltrate into the TME[17]. The expression of mitochondrial fission key regulator dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) in HCC cells is positively correlated with the infiltration of TAMs in tumor tissues. Drp1-regulated mitochondrial fission induces cytosolic mitochondrial DNA stress, which activates Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9/nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling pathway, thereby promoting CCL2 expression in HCC cells and promoting the recruitment of TAMs into tumor tissues[18].

Different subsets of TAMs in HCC exhibit distinct functions. For example, the number of apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-expressing TAMs was found to be increased in tumors that were resistant to immunotherapy[19]. Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis has helped to delineate the immunosuppressive landscape and heterogeneity of TAMs in HCC[20]. For example, secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1)+ TAMs are enriched in cytokeratin 19-positive HCC, where they promote tumor invasion and metastasis and are associated with poor prognosis[21]. Here, we summarize several subpopulations of TAMs[7,22,23] in HCC and briefly discuss their expression markers, spatial distribution, main functions, and mechanisms of action (Table 1). In the following sections, we discuss the functions of TAMs and the key signaling pathways that regulate their functions in HCC.

| TAM subpopulation | Key markers | Main functions | Mechanisms of action | Ref. |

| M0 (FCGR1A) | CD86, TNFRSF14, SIGLEC10 | Interacting with tumor cells or other immune cells through their ligands or receptors | Ligand/receptor interaction to impact anti-tumor immunity | Ye et al[22] |

| M1(FCGR1A) | CD86, TNFRSF14, SIGLEC10 | |||

| M2 (MSR1, CD163, and CD209) | CD86, SIGLEC10, TNFRSF14, LGALS9, HAVCR2, ITGB2 | |||

| TAMs | C1QA, APOE, C1QB, TREM2, ID3, MITF, RUNX2, MAF | High TAMs were associated with poor prognosis | Expression of SLC40A1 and GPNMB | Zhang et al[7] |

| Myeloid-derived suppressor cell-like macrophage | THBS1, BCL3, NR4A1, RXRA, TCF25 | |||

| SPP1+BCL2A1+ TAMs | SPP1 BCL2A1 | HCC patients with high SPP1+BCL2A1+ TAM expression further exhibited significantly poorer responses to anti-PD-1 therapy | Suppression of T cell function | Lai et al[23] |

TAMs contribute to an immunosuppressive TME in HCC and promote therapeutic resistance. In this section, we review the major functions of TAMs in HCC.

The population of CD163-expressing M2 macrophages in human patients is significantly and positively associated with HCC metastasis and poor prognosis[24]. Exosomes derived from M2 macrophages express cytokines including granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (also known as CCL-2), and interleukin (IL)-4, which can promote the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and angiogenesis and attract more macrophages[24]. G-CSF, particularly, can inhibit M1 macrophage polarization by suppressing inducible nitric oxide synthase expression, thereby supporting tumor growth. Mechanistically, G-CSF enhances the secretion of angiogenic factors such as VEGF, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)[25]. In addition, TAMs interact with tumor vascular endothelial cells through different ligand-receptor pairs, further contributing to angiogenesis in HCC[26]. Moreover, tumor endothelial cells drive M2 macrophage polarization via the secretion of IL-4, inducing immunosuppression in HCC[27].

Liver fibrosis is commonly associated with MASLD and CCL4-induced liver injury during HCC development[28,29]. Secreted macrophage markers, such as soluble CD163 (sCD163), chitinase-3-like protein 1 (CHI3 L1, also known as YKL-40), and soluble Siglec-7, can predict the progression of liver fibrosis in patients with MASLD[29,30]. TAMs advance liver fibrosis by secreting profibrogenic cytokines, including TGF-β, platelet-derived growth factors (PDGF), oncostatin M (OSM), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1β, and chemokines[31]. For example, TGF-β activates intracellular suppressor of mother against decapentaplegic signaling pathways to promote the activation and trans-differentiation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) to myofibroblasts, consequently advancing fibrosis[32]. PDGF-β can promote liver fibrosis by upregulating TGF-β expression and also increases the expression of VEGF and platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1, all these factors playing important roles in HCC[33]. OSM can upregulate the TGF-β and PDGF in liver macrophages and induce tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 expression in HSCs, thereby driving liver fibrosis and collagen deposition[34]. Finally, proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, are secreted from macrophages during liver injury and inflammation to promote the activation of HSCs and other hepatic cells, advancing extracellular matrix protein deposition[35,36].

TAMs are closely associated with tumor metastasis and poor prognosis in HCC. Macrophage-secreted IL-6 in the HCC microenvironment can promote tumor cell migration by activating the Janus kinase-1/ARF6-GTPase-activating protein/ARF6 signaling pathway[37]. SPP1+ TAMs shown in hepatitis B virus-related HCC displayed M2-like macrophage features. These TAMs had the activation of the VEGFA/MMP9 angiogenic signaling pathway, driving the invasion and metastasis of HCC stem cells and correlating with poor prognosis[21]. Exosomes derived from M2-like TAMs enhance EMT, angiogenesis, and vascular permeability by secreting cytokines G-CSF, GM-CSF, and VEGF, promoting tumor cell metastasis[24].

Mitochondrial DNA released from tumor cells promotes M2 polarization of TAMs in HCC by activating the TLR9/NF-κB signaling pathway. M2-like TAMs cause an immunosuppressive microenvironment, resulting in HCC cell resistance to sorafenib[38]. The stress of mitochondrial DNA can also increase CCL2 expression in tumor cells to recruit more TAMs[18]. These TAMs can induce T cell exhaustion to suppress immunotherapy. In contrast, targeting TAMs (e.g., CX3CR1+ TAMs driven by prostaglandin E2 from HCC cells) can improve the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy against HCC[39].

TAMs play a key role in contributing to immune evasion and resistance to immunotherapy. In a Cre-loxP system knockout model, depletion of xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) in monocyte-derived macrophages or Kupffer cells in orthotopic HCC-bearing mice led to M2 macrophage polarization and cytotoxic CD8+ T cell exhaustion, thereby inducing immunosuppressive TME[40]. Mechanistically, XOR deficiency enhanced the activity of isocitrate dehydrogenase 3α in monocyte-derived macrophages, increasing the activity of α-ketoglutarate production and driving M2 polarization. Conversely, loss of ketone metabolic enzyme 3-oxoacid CoA-transferase 1 in TAMs increased CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity and suppressed arginase 1 expression and M2 polarization[41]. PD-L1+ TAMs enriched in HCC can drive CD8+ T cell exhaustion[42]. In vitro assay illustrated that GM-CSF can induce PD-L1 expression in macrophages to induce CD8+ T cell dysfunction, characterized by an increased expression of T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 and a decreased expression of granzyme B[42]. Overall, TAMs in HCC promote cancer cell proliferation, invasion, EMT, and metastasis, fostering an immunosuppressive microenvironment to induce HCC progression and drive therapeutic resistance (Figure 1).

In this section, several molecular signaling pathways are reviewed based on recently published studies.

Tumor cell-derived lactate promotes acetate production in TAMs by activating the lipid peroxidation-ALDH2 pathway in HCC. Acetate uptake in HCC cells can induce their metastasis in vitro and in vivo. Genetic ablation of ALDH2 in TAMs can decrease the accumulation of acetate in HCC cells and inhibit their lung metastases[43].

The expression of ApoE is positively associated with poor overall survival in HCC patients[19]. The proportion of ApoE+ macrophages is negatively correlated with CD8+ T cell infiltration, which is notably increased in tumors of non-responding HCC patients undergoing immune checkpoint blockade therapy[19]. ApoE deficiency in macrophages can increase CD8+ T cell infiltration, leading to the retardation of tumor growth. Furthermore, blockade of ApoE exhibits a synergistic effect with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in suppressing tumor growth in mice[19].

Intrinsic expression of osteopontin (OPN) in HCC tumor cells enhances M2 macrophage polarization and recruitment by activating the colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF1)/CSF1 receptor (CSF1R) signaling pathway. Moreover, OPN expression level is positively associated with PD-L1 expression in the TME[44]. Inhibiting the expression of CSF1R in TAMs promotes M1 macrophage polarization and enhances the phagocytic function of macrophages to HCC cells[45].

Inhibition or depletion of fatty acid binding protein 5 (FABP5) suppresses obesity-associated HCC in mice by promoting tumor cell ferroptosis[46]. Pharmacological inhibition of FABP5 enhances CD8+ T cell activation and M1 macrophage polarization, as evidenced by increased expression of CD80 and CD86[46]. FABP5-expressing exosomes from HCC cells reprogram lipid metabolism in macrophages by activating the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) signaling pathway and inhibiting the PPARα signaling pathway, thereby inducing M2 macrophage polarization and contributing to HCC progression[47]. Additionally, FABP5 regulates unsaturated fatty acid metabolism in TAMs by activating the PPARγ signaling pathway, leading to elevated expression of PD-L1, PD-L2, and galectins. These factors suppress T cell activation and proliferation, inducing an immunosuppressive microenvironment and advancing HCC progression[48].

Patients with a high proportion of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1)+ macrophages have longer overall survival and recurrence-free survival compared to those with a low percentage of GPER1+ macrophages[49]. GPER1 activation negatively regulates TAM proliferation in HCC by suppressing the mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathway. In addition, GPER1 activation induces PD-L1 suppression on macrophages. Treatment with a GPER1 agonist successfully retarded tumor growth in mice[49].

Hypoxia increases the expression of RE1 silencing transcription factor corepressor 2 (RCOR2) in HCC via activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha, which is linked to poor prognosis[50]. RCOR2 promotes HCC cell proliferation and metastasis. Moreover, sumoylation of RCOR2 increases M2 macrophage polarization and CD8+ T cell exhaustion by upregulating leukemia inhibitory factor transcription in tumor cells, thereby facilitating immune evasion[50].

Patients with lower expression of NLRP6 in macrophages within HCC tissues have better survival outcomes[51]. Global knockout of Nlpr6 or macrophage-specific knockout of Nlpr6 in mice results in delayed tumor growth compared to wild-type controls. Additionally, adoptive transfer of Nlpr6-deficient macrophages inhibits HCC progression in vivo[51]. Further molecular mechanistic studies show that NLRP6 suppresses macrophage phagocytosis by interacting with extended synaptotagmin protein 1[51].

Sirtuin 4 (SIRT4), a tumor suppressor gene, is expressed at lower levels in HCC tumor tissues compared to adjacent peritumor tissues, and its downregulation is associated with increased macrophage infiltration. Reduced SIRT4 expression is also observed in M2 macrophages in peritumor tissues, which is correlated with poorer survival outcomes in HCC patients[52].

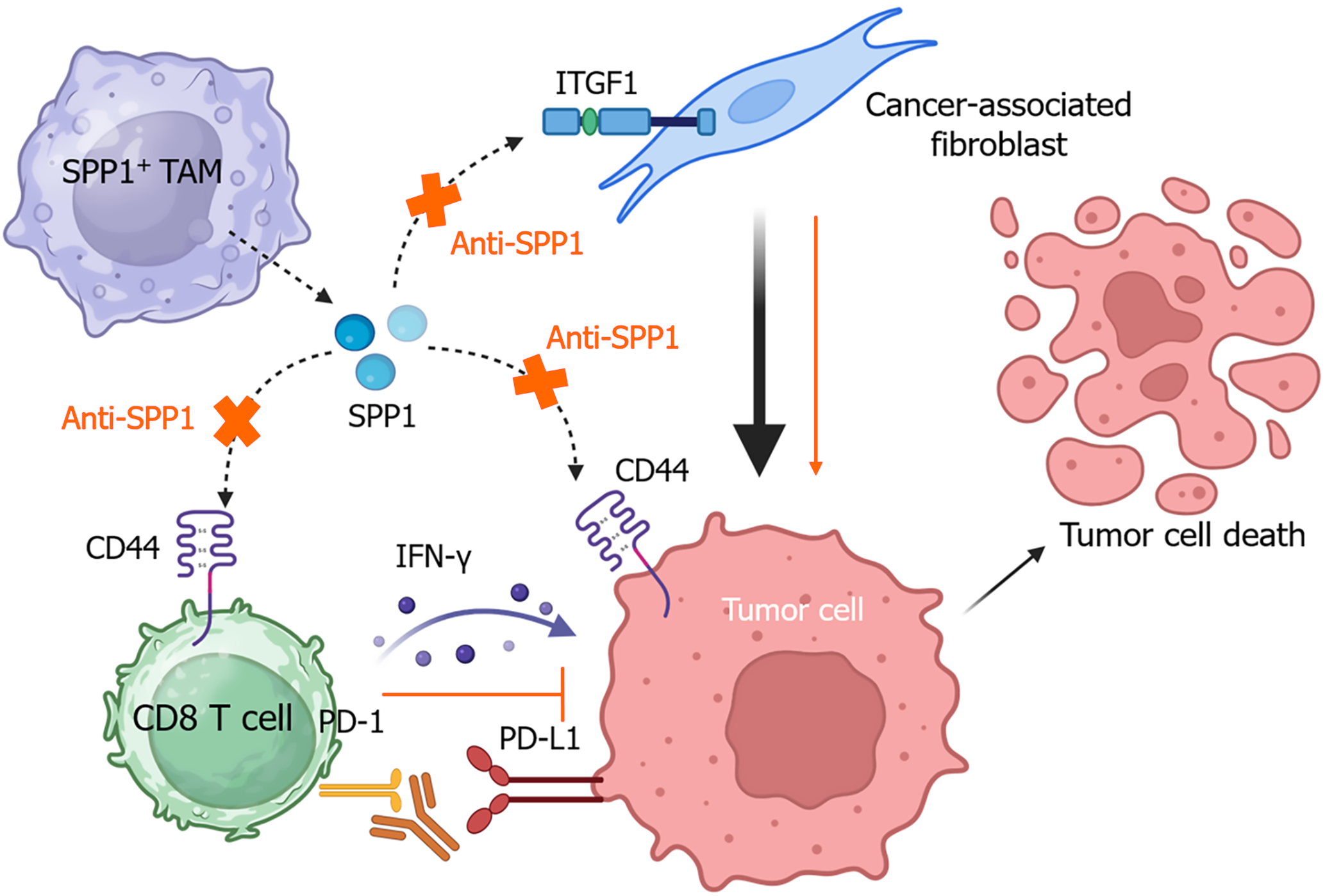

Single-cell RNA sequencing has demonstrated that SPP1+ TAMs, as a distinct cluster of TAMs in HCC, contribute to metabolic dysregulation and immunosuppression by suppressing CD8+ T cell infiltration[53]. SPP1+ TAMs are enriched in the immunosuppressive TME enriched with Tregs and exhausted CD8+ T cells[54]. Another study reports that SPP1+ TAMs are highly enriched around alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)-positive HCC cells[55]. SPP1 facilitates communication between TAMs, tumor cells, and T cells via CD44 and regulates their interactions with cancer-associated fibroblasts through integrin subunit beta 1[56]. The SPP1-CD44 axis also mediates CD8+ T cell exhaustion in other cancers, including ovarian cancer[57] and oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma[58].

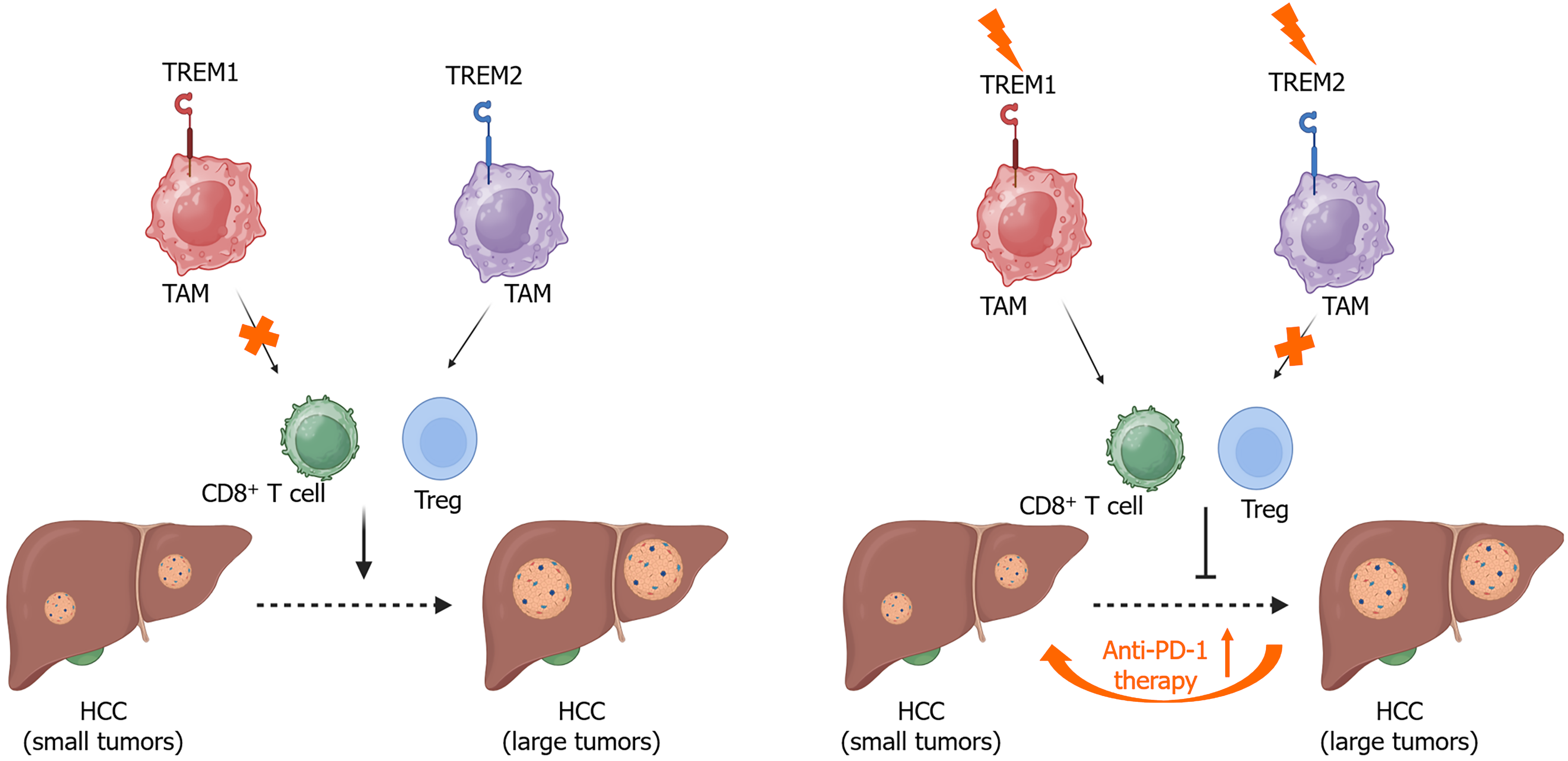

Under hypoxic conditions, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α activates the expression of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (TREM-1) in TAMs (Figure 2), promoting HCC progression by recruiting CCR6+ forkhead box protein P3+ Tregs and impairing CD8+ T cell function[10]. Knockdown of TREM-1 in macrophages suppresses M2 macrophage polarization by inhibiting phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT)/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway, thereby reducing migration and invasion of HCC cells[59].

Oxidized low-density lipoprotein produced by cancer cells can drive TREM2+ TAMs to suppress CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity, promoting tumor progression[60]. TREM2+ TAMs also contribute to the progression of MASH to HCC. Clinically, TREM2 expression is positively associated with immunosuppression, characterized by the accumulation of neutrophil extracellular traps and the infiltration of Tregs and PD-1+ Eomes+ CD8+ T cells[61]. Myeloid-specific knockout of TREM2 improves the anti-PD-1 therapeutic efficacy in MASH-associated HCC (Figure 2) and leads to the accumulation of proinflammatory Ly6Chigh CX3CR1low macrophages[61].

Lenvatinib resistance in HCC can enhance the deleterious role of TAMs in tumor progression[62]. The expression of VEGF is increased in lenvatinib-resistant HCC. VEGF receptor 2 expression in monocyte-derived macrophages treated with the conditioned medium from lenvatinib-resistant HCC cells is significantly higher compared to naive TAMs, displaying M2-like macrophage phenotype[63].

Notably, these signaling pathways are associated with immunosuppressive functions of TAMs in HCC by modulating immunosuppressive cell infiltration, M2-like macrophage polarization, and immune checkpoint expression. However, the interactions of these molecules are not well known.

CCR2+ TAMs have been shown to accumulate around the vascular vessels of HCC borders[64]. CCL2 is overexpressed in liver cancers of human patients and functions as a prognostic biomarker[65]. Treatment with a pharmacologic antagonist of chemokine CCL2 can inhibit the infiltration of CCR2+ TAMs into the fibrotic HCC microenvironment, thereby reducing tumor volume and vascularization[64]. Blocking the CCL2/CCR2 signaling pathway also suppresses monocyte recruitment and enhances CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity, resulting in suppression of HCC growth[65]. Similarly, treatment with a CCR2 antagonist can also increase the number of intratumor CD8+ T cells and suppress TAMs-induced immunosuppressive TME in HCC. This CCR2 antagonist, a natural product isolated from Abies georgei, enhances the therapeutic efficacy of sorafenib without significant side effects[66].

Tumor cell-derived CCL28 chemoattracts the infiltration of TAMs through its receptor CCR10, contributing to immunosuppression and therapeutic resistance to lenvatinib. Selective blockade of CCR10 with an antagonist can reduce TAM recruitment and improve the therapeutic effectiveness of levantinib for HCC[67].

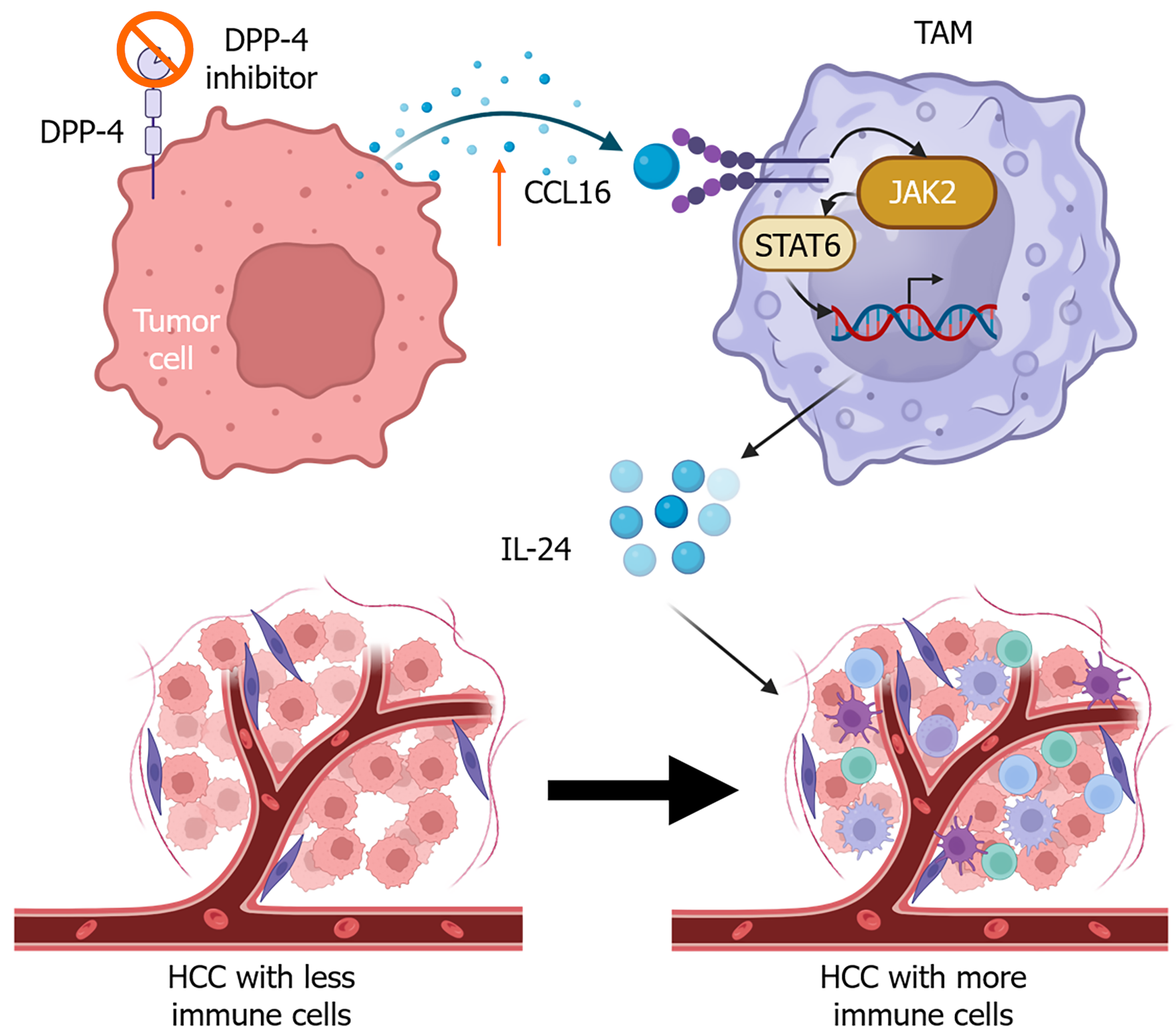

Another study showed that treatment with a dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor increases the expression of CCL16 in tumor cells, promoting vascular normalization and reversing immunosuppression[68]. Tumor cells derived CCL16 interacts with ICAM-1 on macrophages (Figure 3), increasing IL-24 expression in macrophages through activation of the Janus kinase 2/signal transduction and transcription activation 6 signaling pathway[68].

D-lactate, a gut microbial metabolite, can repolarize M2-like TAMs toward M1 by inhibiting PI3K/AKT signaling and activating the NF-κB pathway via interaction with TLR2 and/or TLR9[69]. A nano-formulation, M2 macrophage-binding peptide-targeted HCC membrane-coated poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticle, was applied to deliver D-lactate. This nanoparticle functioned in the HCC TME to transform TAMs from M2 to M1 and to enhance the efficacy of the anti-CD47 antibody, thereby improving the survival of HCC-bearing mice.

Oleanolic acid (OA), a natural metabolite from plants, inhibits M2 macrophage polarization induced by hypoxic HCC-derived exosomes in vitro. OA treatment reduces the number of M2 macrophages while enhancing the number of CD8+ T cells in the Hepa1-6-induced liver cancer mouse model[70].

Suppression of long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) cyclooxygenase-2 (cox-2) by small interfering RNAs can reduce M1 macrophage polarization while increasing the expression of M2 macrophage markers such as arginase-1, IL-10, and found in inflammatory zone 1, resulting in HCC cell proliferation and migration[71]. Overexpression of lncRNA cox-2 is thus a potential strategy to promote M1 macrophage polarization and suppress HCC growth. Another study shows that overexpression of lncRNA MEG3 can induce M1 macrophage polarization, characterized by an increased expression of T helper (Th) 1 cytokines (IL-2, IL-12, IFN-γ) and a decreased expression of CSF1 and Th2 cytokines. This polarization suppresses HCC cell growth, invasion, and migration. In addition, overexpression of lncRNA MEG3 in HCC cells can also inhibit tumor growth in xenograft HCC models[72].

As previously mentioned, SPP1+ TAMs represent a major population of macrophages in HCC. Targeting the SPP1-CD44 axis with either anti-SPP1 or anti-CD44 antibody alone can recover T cell function in vitro and significantly inhibit tumor growth in vivo. These antibodies also show a synergistic effect with anti-PD-1 in suppressing tumor growth and improving CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity[55], as shown in Figure 4.

Targeting TAMs provides a promising therapeutic strategy for HCC treatment. However, off-target effects and adverse consequences may be associated with these therapies. Because TAMs also share many markers with normal macrophages in different tissues, disrupting TAM function may impair tissue immunity[73]. Therefore, tumor-targeting delivery of therapeutic agents or modifications can improve precision and reduce potential side effects and adverse consequences.

Serum levels of sCD163 are significantly increased in patients with MASLD-associated HCC compared to those without HCC[29]. High serum levels of sCD163 are associated with the mortality of patients with HCC[74]. Serum cell death markers M30 and M65 are useful for predicting liver inflammation and fibrosis in patients with MASLD. M65 can also help distinguish the grades of steatosis[75]. Elevated levels of M65 and sCD163 are associated with the mortality of patients with HCC[74]. CHI3 L1, also known as YKL-40, is a glycoprotein that is highly expressed in liver macrophages. Serum YKL-40 levels are significantly higher in patients with non-cirrhotic MASLD who develop HCC than in those without HCC. In addition, YKL-40 is highly expressed by macrophages in the liver tissues of patients with MASLD, which is significantly associated with liver fibrosis[76]. YKL-40 may also serve as a prognostic marker for predicting recurrence and graft liver fibrosis in patients with virus-associated HCC or those undergoing liver transplantation[77]. Furthermore, SPP1+ macrophages have been detected to be co-located with cancer stem cells in HCC, which is correlated with a worse prognosis[78].

In addition, molecular imaging strategies by visualization of TAMs were applied in HCC with nanoprobes, nanobubbles, or fluorescence-conjugated polypeptides targeting molecular biomarkers, such as the mannose receptor or CD206[79] and CSF1R[80].

Accumulating studies indicate that microRNAs play important roles in HCC cell growth and metastasis, such as miR-17 cluster[81] and miR-19a-3p[82]. TAMs can regulate their expression in tumor cells. For example, CXCL8 expressed by TAMs stimulates the expression of miR-18a and miR-19a to increase HCC cell growth and metastasis[81]. In addition, M2-like macrophage-derived miR-23a-3p enhances HCC metastasis by promoting EMT, vascular permeability, and angiogenesis[24].

TAMs contribute to the initiation and progression of HCC. Tumor cells can upregulate the expression of cytokines (e.g., TGF-β1) and chemokines (e.g., CCL2) to inhibit the cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells and promote the recruitment of TAMs and other immunosuppressive cells (e.g., Tregs)[83-85]. Better understanding the gene expression files and metabolic features of TAMs in HCC from different etiologies (e.g., MASLD and viral infection) improves the precise investigation of the distinct functions and molecular biomarkers or targets of TAMs for HCC diagnosis and therapy. Currently, limited clinical trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov/, trial number NCT04105335) have demonstrated the promising effects of strategies targeting TAMs or immunosuppressive cells in the treatment of HCC. MTL-CEBP, a first-in-class small activating RNA oligonucleotide drug, activates the transcriptional factor C/EBP-α (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha) to regulate myeloid cell function and enhance anti-tumor responses[86,87]. A phase 1 clinical study (No. NCT04105335) showed that a combined therapy of MTL-CEBPA (MTL-CCAAT enhancer-binding protein alpha/CEBPA) with pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody) significantly decreased the proportion of M2 macrophages and ameliorated immunosuppression in TME[88]. With the new findings in pre-clinical models, selected targets are expected to be tested in organoid models of human HCC and clinical trials. Moreover, macrophage-targeted strategies or drug delivery systems are needed to modulate TAM function for effective HCC treatment. For the early diagnosis of HCC, new scoring systems and biomarkers have been developed or are under development. Several algorithms have been created to facilitate early diagnosis of HCC in patients with chronic liver diseases[89,90], including the established GALAD, GAAP, and ASAP algorithms, which are based on gender, age, AFP, lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive AFP, and protein induced by vitamin K absence-II. Emerging biomarkers such as circulating tumor DNA, microRNAs, lncRNAs, extracellular vesicles, and metabolomic biomarkers show promise for identifying individuals at risk for HCC[91,92]. Artificial intelligence or machine learning should be applied to increase the precision of HCC diagnosis in clinical applications[93]. Overall, TAMs play essential roles in the TME of HCC and represent promising therapeutic targets for the treatment of HCC with the advancement of modern technologies.

| 1. | Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, Lesi O, Cabasag CJ, Vignat J, Laversanne M, McGlynn KA, Soerjomataram I. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1598-1606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 1424] [Article Influence: 356.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Huang DQ, Singal AG, Kono Y, Tan DJH, El-Serag HB, Loomba R. Changing global epidemiology of liver cancer from 2010 to 2019: NASH is the fastest growing cause of liver cancer. Cell Metab. 2022;34:969-977.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 99.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, Romero D, Abdelmalek MF, Anstee QM, Arab JP, Arrese M, Bataller R, Beuers U, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Byrne CD, Castro Narro GE, Chowdhury A, Cortez-Pinto H, Cryer DR, Cusi K, El-Kassas M, Klein S, Eskridge W, Fan J, Gawrieh S, Guy CD, Harrison SA, Kim SU, Koot BG, Korenjak M, Kowdley KV, Lacaille F, Loomba R, Mitchell-Thain R, Morgan TR, Powell EE, Roden M, Romero-Gómez M, Silva M, Singh SP, Sookoian SC, Spearman CW, Tiniakos D, Valenti L, Vos MB, Wong VW, Xanthakos S, Yilmaz Y, Younossi Z, Hobbs A, Villota-Rivas M, Newsome PN; NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023;78:1966-1986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1658] [Cited by in RCA: 1816] [Article Influence: 605.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tabori NE, Sivananthan G. Treatment Options for Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2020;37:448-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang C, Yang M, Ericsson AC. The Potential Gut Microbiota-Mediated Treatment Options for Liver Cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:524205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tong J, Tan Y, Ouyang W, Chang H. Targeting immune checkpoints in hepatocellular carcinoma therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2025;14:65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang Q, He Y, Luo N, Patel SJ, Han Y, Gao R, Modak M, Carotta S, Haslinger C, Kind D, Peet GW, Zhong G, Lu S, Zhu W, Mao Y, Xiao M, Bergmann M, Hu X, Kerkar SP, Vogt AB, Pflanz S, Liu K, Peng J, Ren X, Zhang Z. Landscape and Dynamics of Single Immune Cells in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell. 2019;179:829-845.e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 763] [Cited by in RCA: 1120] [Article Influence: 160.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shang C, He T, Zhang Y. Tumor-associated macrophage-based predictive and prognostic model for hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2025;20:e0325120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wan S, Kuo N, Kryczek I, Zou W, Welling TH. Myeloid cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015;62:1304-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wu Q, Zhou W, Yin S, Zhou Y, Chen T, Qian J, Su R, Hong L, Lu H, Zhang F, Xie H, Zhou L, Zheng S. Blocking Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells-1-Positive Tumor-Associated Macrophages Induced by Hypoxia Reverses Immunosuppression and Anti-Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Resistance in Liver Cancer. Hepatology. 2019;70:198-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 33.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhou J, Ding T, Pan W, Zhu LY, Li L, Zheng L. Increased intratumoral regulatory T cells are related to intratumoral macrophages and poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1640-1648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ning J, Ye Y, Bu D, Zhao G, Song T, Liu P, Yu W, Wang H, Li H, Ren X, Ying G, Zhao Y, Yu J. Imbalance of TGF-β1/BMP-7 pathways induced by M2-polarized macrophages promotes hepatocellular carcinoma aggressiveness. Mol Ther. 2021;29:2067-2087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Fan QM, Jing YY, Yu GF, Kou XR, Ye F, Gao L, Li R, Zhao QD, Yang Y, Lu ZH, Wei LX. Tumor-associated macrophages promote cancer stem cell-like properties via transforming growth factor-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2014;352:160-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wan S, Zhao E, Kryczek I, Vatan L, Sadovskaya A, Ludema G, Simeone DM, Zou W, Welling TH. Tumor-associated macrophages produce interleukin 6 and signal via STAT3 to promote expansion of human hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1393-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 554] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cheng K, Cai N, Yang X, Li D, Zhu J, Yang HY, Liu S, Ning D, Liang H, Zhao J, Zhang Z, Zhang W. Short-term starvation boosts anti-PD-L1 therapy by reshaping tumor-associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2025;82:1414-1431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhang P, Chen Z, Kuang H, Liu T, Zhu J, Zhou L, Wang Q, Xiong X, Meng Z, Qiu X, Jacks R, Liu L, Li S, Lumeng CN, Li Q, Zhou X, Lin JD. Neuregulin 4 suppresses NASH-HCC development by restraining tumor-prone liver microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2022;34:1359-1376.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Xie M, Lin Z, Ji X, Luo X, Zhang Z, Sun M, Chen X, Zhang B, Liang H, Liu D, Feng Y, Wang Y, Li Y, Liu B, Huang W, Xia L. FGF19/FGFR4-mediated elevation of ETV4 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by upregulating PD-L1 and CCL2. J Hepatol. 2023;79:109-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bao D, Zhao J, Zhou X, Yang Q, Chen Y, Zhu J, Yuan P, Yang J, Qin T, Wan S, Xing J. Mitochondrial fission-induced mtDNA stress promotes tumor-associated macrophage infiltration and HCC progression. Oncogene. 2019;38:5007-5020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Xia X, Zhou Z, Zheng X, Tu C, Liu H, Hu Z, Ma T, Tang Y, Chen W. APOE deficiency triggers anti-tumour activity of macrophages in liver cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2025;32:949-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ho DW, Tsui YM, Chan LK, Sze KM, Zhang X, Cheu JW, Chiu YT, Lee JM, Chan AC, Cheung ET, Yau DT, Chia NH, Lo IL, Sham PC, Cheung TT, Wong CC, Ng IO. Single-cell RNA sequencing shows the immunosuppressive landscape and tumor heterogeneity of HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yang CL, Song R, Hu JW, Huang JT, Li NN, Ni HH, Li YK, Zhang J, Lu Z, Zhou M, Wang JD, Li MJ, Zhan GH, Peng T, Yu HP, Qi LN, Wang QY, Xiang BD. Integrating single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing reveals CK19 + cancer stem cells and their specific SPP1 + tumor-associated macrophage niche in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int. 2024;18:73-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ye J, Lin Y, Liao Z, Gao X, Lu C, Lu L, Huang J, Huang X, Huang S, Yu H, Bai T, Chen J, Wang X, Xie M, Luo M, Zhang J, Wu F, Wu G, Ma L, Xiang B, Li L, Li Y, Luo X, Liang R. Single cell-spatial transcriptomics and bulk multi-omics analysis of heterogeneity and ecosystems in hepatocellular carcinoma. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2024;8:262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lai CH, Hung YP, Tseng PC, Satria RD, Lin CF. Intratumoral SPP1(+)BCL2A1(+) Tumor-Associated Macrophages Predict Poor Response to PD1 Blockade. Diagnostics (Basel). 2025;15:2680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lu Y, Han G, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Li Z, Wang Q, Chen Z, Wang X, Wu J. M2 macrophage-secreted exosomes promote metastasis and increase vascular permeability in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21:299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cao H, Wang S. G-CSF promotes the development of hepatocellular carcinoma by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in TAM. Aging (Albany NY). 2024;16:10799-10812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhang CY, Yang M. Targeting tumor vascular endothelial cells for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:110114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Matoba D, Noda T, Kobayashi S, Sakano Y, Matsumoto K, Yamanaka C, Sasaki K, Hasegawa S, Iwagami Y, Yamada D, Tomimaru Y, Akita H, Takahashi H, Asaoka T, Shimizu J, Wada H, Doki Y, Eguchi H. Tumor Endothelial Cells Induce M2 Macrophage Polarization via IL-4, Enhancing Tumor Growth in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2025;116:2972-2985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhang Q, Liu Y, Ren L, Li J, Lin W, Lou L, Wang M, Li C, Jiang Y. Proteomic analysis of DEN and CCl(4)-induced hepatocellular carcinoma mouse model. Sci Rep. 2024;14:8013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kawanaka M, Nishino K, Kawada M, Ishii K, Tanikawa T, Katsumata R, Urata N, Nakamura J, Suehiro M, Haruma K, Kawamoto H. Soluble CD163 is a predictor of fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma development in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yoshio S, Kanto T. Macrophages as a source of fibrosis biomarkers for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Immunol Med. 2021;44:175-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Matsuda M, Seki E. Hepatic Stellate Cell-Macrophage Crosstalk in Liver Fibrosis and Carcinogenesis. Semin Liver Dis. 2020;40:307-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fabregat I, Moreno-Càceres J, Sánchez A, Dooley S, Dewidar B, Giannelli G, Ten Dijke P; IT-LIVER Consortium. TGF-β signalling and liver disease. FEBS J. 2016;283:2219-2232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 499] [Article Influence: 49.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Maass T, Thieringer FR, Mann A, Longerich T, Schirmacher P, Strand D, Hansen T, Galle PR, Teufel A, Kanzler S. Liver specific overexpression of platelet-derived growth factor-B accelerates liver cancer development in chemically induced liver carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1259-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Matsuda M, Tsurusaki S, Miyata N, Saijou E, Okochi H, Miyajima A, Tanaka M. Oncostatin M causes liver fibrosis by regulating cooperation between hepatic stellate cells and macrophages in mice. Hepatology. 2018;67:296-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Márquez-Quiroga LV, Vargas-Pozada EE, Cardoso-Lezama I, Ramos-Tovar E, Vásquez-Garzón VR, Piña-Vázquez C, Villa-Treviño S, Arellanes-Robledo J, Muriel P. Chronological activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome/pyroptosis pathway in the progression from metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease to hepatocellular carcinoma. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2025;35:1103-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhang CY, Liu S, Yang M. Treatment of liver fibrosis: Past, current, and future. World J Hepatol. 2023;15:755-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Li T, Song X, Chen J, Li Y, Lin J, Li P, Yu S, Durojaye OA, Yang F, Liu X, Li J, Cheng S, Yao X, Ding X. Kupffer Cell-derived IL6 Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metastasis Via the JAK1-ACAP4 Pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2025;21:285-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Yang Q, Cui M, Wang J, Zhao Y, Yin W, Liao Z, Liang Y, Jiang Z, Li Y, Guo J, Qi L, Chen J, Zhao J, Bao D, Xu ZX. Circulating mitochondrial DNA promotes M2 polarization of tumor associated macrophages and HCC resistance to sorafenib. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16:153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Xiang X, Wang K, Zhang H, Mou H, Shi Z, Tao Y, Song H, Lian Z, Wang S, Lu D, Wei X, Xie H, Zheng S, Wang J, Xu X. Blocking CX3CR1+ Tumor-Associated Macrophages Enhances the Efficacy of Anti-PD1 Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2024;12:1603-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Lu Y, Sun Q, Guan Q, Zhang Z, He Q, He J, Ji Z, Tian W, Xu X, Liu Y, Yin Y, Zheng C, Lian S, Xu B, Wang P, Jiang R, Sun B. The XOR-IDH3α axis controls macrophage polarization in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2023;79:1172-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Zhu CX, Yan K, Chen L, Huang RR, Bian ZH, Wei HR, Gu XM, Zhao YY, Liu MC, Suo CX, Li ZK, Yang ZY, Lu MQ, Hua XF, Li L, Zhao ZB, Sun LC, Zhang HF, Gao P, Lian ZX. Targeting OXCT1-mediated ketone metabolism reprograms macrophages to promote antitumor immunity via CD8(+) T cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2024;81:690-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Nosaka T, Ohtani M, Yamashita J, Murata Y, Akazawa Y, Tanaka T, Takahashi K, Naito T, Imamura Y, Koneri K, Goi T, Nakamoto Y. PD-L1(+) tumor-associated macrophages induce CD8(+) T Cell exhaustion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Neoplasia. 2025;69:101234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Shen L, Wang S, Gao C, Li Q, Feng S, Sun W, Liu X, Ba Y, Chu Y, Zhou Y, Pan J, Xu H, Zhang X, Zhu W, Qin L, Lu M. Tumour-associated macrophages serve as an acetate reservoir to drive hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. Nat Metab. 2025;7:2268-2283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Zhu Y, Yang J, Xu D, Gao XM, Zhang Z, Hsu JL, Li CW, Lim SO, Sheng YY, Zhang Y, Li JH, Luo Q, Zheng Y, Zhao Y, Lu L, Jia HL, Hung MC, Dong QZ, Qin LX. Disruption of tumour-associated macrophage trafficking by the osteopontin-induced colony-stimulating factor-1 signalling sensitises hepatocellular carcinoma to anti-PD-L1 blockade. Gut. 2019;68:1653-1666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 48.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lu J, Zhang T, Jiang C, Hu H, Fei Y, Yang Y, An H, Qin H, Zhu Z, Yang Y, Tian S, Huang L, Zhao H. Ganoderic acid A regulates CSF1R to reprogram tumor-associated macrophages for immune therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;161:114989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Sun J, Esplugues E, Bort A, Cardelo MP, Ruz-Maldonado I, Fernández-Tussy P, Wong C, Wang H, Ojima I, Kaczocha M, Perry R, Suárez Y, Fernández-Hernando C. Fatty acid binding protein 5 suppression attenuates obesity-induced hepatocellular carcinoma by promoting ferroptosis and intratumoral immune rewiring. Nat Metab. 2024;6:741-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Luo S, Tang R, Jiang L, Luo Q, Fu J, Wu B, Wang G. Exosomal FABP5 drives HCC progression via macrophage lipid metabolism and immune microenvironment remodeling. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1644645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Yang X, Deng B, Zhao W, Guo Y, Wan Y, Wu Z, Su S, Gu J, Hu X, Feng W, Hu C, Li J, Xu Y, Huang X, Lin Y. FABP5(+) lipid-loaded macrophages process tumour-derived unsaturated fatty acid signal to suppress T-cell antitumour immunity. J Hepatol. 2025;82:676-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Yang Y, Wang Y, Zou H, Li Z, Chen W, Huang Z, Weng Y, Yu X, Xu J, Zheng L. GPER1 signaling restricts macrophage proliferation and accumulation in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1481972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Jia W, Wang J, Yang W, Ding Z, Liang L, Xu C, Feng Y, Lv Q, Zhu D, Zhao W, Ling X, Yan Y, Ai X, Zhou Y, Kong L, Ding W. Hypoxia-induced RCOR2 promotes macrophage M2 polarization and CD8(+) T-cell exhaustion by enhancing LIF transcription in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13:e012314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Li S, Fu Y, Jia X, Liu Z, Qian Z, Zha H, Lei G, Yu L, Zhang X, Zhang T, Zhang T, Han J, Shi Y, Safadi R, Lu Y. NLRP6 deficiency enhances macrophage-mediated phagocytosis via E-Syt1 to inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Gut. 2025;74:1883-1895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Li Z, Li H, Zhao ZB, Zhu W, Feng PP, Zhu XW, Gong JP. SIRT4 silencing in tumor-associated macrophages promotes HCC development via PPARδ signalling-mediated alternative activation of macrophages. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Xu WX, Ye YM, Chen JL, Guo XY, Li C, Luo J, Lu LB, Chen X. SPP1+ tumor-associated macrophages define a high-risk subgroup and inform personalized therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1606195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Gao B, Wang Y, Sun Z, Tang H, Cao Y, Jiang H, Zhang W, Xu Y, Hu B, Liu Z, Mao G, Li X, Li J, Wan T, Liu B, Zhao X, Jiao S, Li C, Lu S. NQO1/p65/CXCL12 Axis-Recruited Tregs Mediate Resistance to Anti-PD-1 Plus Lenvatinib Therapy in PIVKA-II-Positive Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025;12:e11152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | He H, Chen S, Fan Z, Dong Y, Wang Y, Li S, Sun X, Song Y, Yang J, Cao Q, Jiang J, Wang X, Wen W, Wang H. Multi-dimensional single-cell characterization revealed suppressive immune microenvironment in AFP-positive hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Discov. 2023;9:60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Gao J, Li Z, Lu Q, Zhong J, Pan L, Feng C, Tang S, Wang X, Tao Y, Lin J, Wang Q. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals cell subpopulations in the tumor microenvironment contributing to hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1194199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Hou L, Jiang M, Li Y, Cheng J, Liu F, Han X, Guo J, Feng L, Li Z, Yi J, Zhao X, Gao Y, Yue W. Targeting SPP1(+) macrophages via the SPP1-CD44 axis reveals a key mechanism of immune suppression and tumor progression in ovarian cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;160:114906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Wang C, Li Y, Wang L, Han Y, Gao X, Li T, Liu M, Dai L, Du R. SPP1 represents a therapeutic target that promotes the progression of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma by driving M2 macrophage infiltration. Br J Cancer. 2024;130:1770-1782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Chen M, Lai R, Lin X, Chen W, Wu H, Zheng Q. Downregulation of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 inhibits invasion and migration of liver cancer cells by mediating macrophage polarization. Oncol Rep. 2021;45:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Chu T, Zhu G, Tang Z, Qu W, Yang R, Pan H, Wang Y, Tian R, Chen L, Guan Z, Bu Y, Zhao Q, Chen J, Mao S, Fang Y, Gao J, Wu X, Zhou J, Liu W, Ye D, Fan J, Shi Y. Metabolism archetype cancer cells induce protumor TREM2(+) macrophages via oxLDL-mediated metabolic interplay in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2025;16:6770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Wang Z, Zhang Y, Li X, Xia N, Han S, Pu L, Wang X. Targeting Myeloid Trem2 Reprograms the Immunosuppressive Niche and Potentiates Checkpoint Immunotherapy in NASH-Driven Hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Immunol Res. 2025;13:1516-1532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Waki Y, Morine Y, Saito Y, Teraoku H, Yamada S, Ikemoto T, Tominaga T, Shimada M. Lenvatinib-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma promotes malignant potential of tumor-associated macrophages via exosomal miR-301a-3p. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2024;8:1084-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Takehara Y, Waki Y, Morine Y, Saito Y, Teraoku H, Wada Y, Yamada S, Ikemoto T, Shimada M. Vascular endothelial growth factor released from lenvatinib-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma promotes malignant behavior and drug resistance through tumor-associated macrophages. Hepatol Res. 2025;55:752-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Bartneck M, Schrammen PL, Möckel D, Govaere O, Liepelt A, Krenkel O, Ergen C, McCain MV, Eulberg D, Luedde T, Trautwein C, Kiessling F, Reeves H, Lammers T, Tacke F. The CCR2(+) Macrophage Subset Promotes Pathogenic Angiogenesis for Tumor Vascularization in Fibrotic Livers. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;7:371-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Li X, Yao W, Yuan Y, Chen P, Li B, Li J, Chu R, Song H, Xie D, Jiang X, Wang H. Targeting of tumour-infiltrating macrophages via CCL2/CCR2 signalling as a therapeutic strategy against hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2017;66:157-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 591] [Article Influence: 65.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Yao W, Ba Q, Li X, Li H, Zhang S, Yuan Y, Wang F, Duan X, Li J, Zhang W, Wang H. A Natural CCR2 Antagonist Relieves Tumor-associated Macrophage-mediated Immunosuppression to Produce a Therapeutic Effect for Liver Cancer. EBioMedicine. 2017;22:58-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Chen C, Su S, Wang P, Ye X, Yu S, Gong Y, Li Z, Li J, Hu Z, Huang X. Targeting immunosuppressive macrophages by CSRP2-regulated CCL28 signaling sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma to lenvatinib. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13:e012201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Chen K, Feng H, Zhang Y, Pei J, Xu Y, Wei X, Chen Z, Feng Z, Cai L, Li Y, Zhao L, Pan M. Tumor-Derived CCL16 Normalizes Tumor Vasculature through Macrophage ICAM-1 Receptor and Enhances Immunotherapy Efficacy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2025;85:3633-3650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Han S, Bao X, Zou Y, Wang L, Li Y, Yang L, Liao A, Zhang X, Jiang X, Liang D, Dai Y, Zheng QC, Yu Z, Guo J. d-lactate modulates M2 tumor-associated macrophages and remodels immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Adv. 2023;9:eadg2697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Tu X, Lin W, Zhai X, Liang S, Huang G, Wang J, Jia W, Li S, Li B, Cheng B. Oleanolic acid inhibits M2 macrophage polarization and potentiates anti-PD-1 therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting miR-130b-3p-PTEN-PI3K-Akt signaling and glycolysis. Phytomedicine. 2025;141:156750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Ye Y, Xu Y, Lai Y, He W, Li Y, Wang R, Luo X, Chen R, Chen T. Long non-coding RNA cox-2 prevents immune evasion and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by altering M1/M2 macrophage polarization. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:2951-2963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Lin J, Huang J, Tan C, Wu S, Lu X, Pu J. LncRNA MEG3 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma by stimulating macrophage M1 polarization and modulating immune system via inhibiting CSF-1 in vivo/vitro studies. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;281:136459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Malfitano AM, Pisanti S, Napolitano F, Di Somma S, Martinelli R, Portella G. Tumor-Associated Macrophage Status in Cancer Treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:1987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Waidmann O, Köberle V, Bettinger D, Trojan J, Zeuzem S, Schultheiß M, Kronenberger B, Piiper A. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of cell death and macrophage activation markers in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2013;59:769-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Joka D, Wahl K, Moeller S, Schlue J, Vaske B, Bahr MJ, Manns MP, Schulze-Osthoff K, Bantel H. Prospective biopsy-controlled evaluation of cell death biomarkers for prediction of liver fibrosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2012;55:455-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Kumagai E, Mano Y, Yoshio S, Shoji H, Sugiyama M, Korenaga M, Ishida T, Arai T, Itokawa N, Atsukawa M, Hyogo H, Chayama K, Ohashi T, Ito K, Yoneda M, Kawaguchi T, Torimura T, Nozaki Y, Watanabe S, Mizokami M, Kanto T. Serum YKL-40 as a marker of liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Pavicic Saric J, Lulic D, Rogic D, Jadrijevic S, Mikulic D, Filipec Kanizaj T, Prpic N, Bozic LK, Adamovic I, Bacak Kocman I, Sarec Z, Erceg G, Adanic M, Ozegovic Zuljan P, Jadrijevic F, Lulic I. YKL-40 in Virus-Associated Liver Disease: A Translational Biomarker Linking Fibrosis, Hepatocarcinogenesis, and Liver Transplantation. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:9584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Fan G, Xie T, Li L, Tang L, Han X, Shi Y. Single-cell and spatial analyses revealed the co-location of cancer stem cells and SPP1+ macrophage in hypoxic region that determines the poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2024;8:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Jiang C, Cai H, Peng X, Zhang P, Wu X, Tian R. Targeted Imaging of Tumor-Associated Macrophages by Cyanine 7-Labeled Mannose in Xenograft Tumors. Mol Imaging. 2017;16:1536012116689499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Jiang Q, Zeng Y, Xu Y, Xiao X, Liu H, Zhou B, Kong Y, Saw PE, Luo B. Ultrasound Molecular Imaging as a Potential Non-invasive Diagnosis to Detect the Margin of Hepatocarcinoma via CSF-1R Targeting. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Yin Z, Huang J, Ma T, Li D, Wu Z, Hou B, Jian Z. Macrophages activating chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 8/miR-17 cluster modulate hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth and metastasis. Am J Transl Res. 2017;9:2403-2411. [PubMed] |

| 82. | Zhang H, Zhu J, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zhao B, Yang X, Zhou W, Chen B, Zhang S, Huang R, Chen S. miR-19a-3p promotes the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating p53/SOX4. Heliyon. 2024;10:e36282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Jin X, Zhang S, Wang N, Guan L, Shao C, Lin Y, Liu J, Li Y. High Expression of TGF-β1 Contributes to Hepatocellular Carcinoma Prognosis via Regulating Tumor Immunity. Front Oncol. 2022;12:861601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 84. | Chen J, Sun HW, Wang RZ, Zhang YF, Li WJ, Wang YK, Wang H, Jia MM, Xu QX, Zhuang H, Xue N. Glutamate promotes CCL2 expression to recruit tumor-associated macrophages by restraining EZH2-mediated histone methylation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2025;14:2497172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Zhou SL, Zhou ZJ, Hu ZQ, Huang XW, Wang Z, Chen EB, Fan J, Cao Y, Dai Z, Zhou J. Tumor-Associated Neutrophils Recruit Macrophages and T-Regulatory Cells to Promote Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Resistance to Sorafenib. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1646-1658.e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 601] [Cited by in RCA: 658] [Article Influence: 65.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 86. | Sarker D, Plummer R, Meyer T, Sodergren MH, Basu B, Chee CE, Huang KW, Palmer DH, Ma YT, Evans TRJ, Spalding DRC, Pai M, Sharma R, Pinato DJ, Spicer J, Hunter S, Kwatra V, Nicholls JP, Collin D, Nutbrown R, Glenny H, Fairbairn S, Reebye V, Voutila J, Dorman S, Andrikakou P, Lloyd P, Felstead S, Vasara J, Habib R, Wood C, Saetrom P, Huber HE, Blakey DC, Rossi JJ, Habib N. MTL-CEBPA, a Small Activating RNA Therapeutic Upregulating C/EBP-α, in Patients with Advanced Liver Cancer: A First-in-Human, Multicenter, Open-Label, Phase I Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:3936-3946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Hashimoto A, Sarker D, Reebye V, Jarvis S, Sodergren MH, Kossenkov A, Sanseviero E, Raulf N, Vasara J, Andrikakou P, Meyer T, Huang KW, Plummer R, Chee CE, Spalding D, Pai M, Khan S, Pinato DJ, Sharma R, Basu B, Palmer D, Ma YT, Evans J, Habib R, Martirosyan A, Elasri N, Reynaud A, Rossi JJ, Cobbold M, Habib NA, Gabrilovich DI. Upregulation of C/EBPα Inhibits Suppressive Activity of Myeloid Cells and Potentiates Antitumor Response in Mice and Patients with Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:5961-5978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Plummer R, Sodergren MH, Hodgson R, Ryan BM, Raulf N, Nicholls JP, Reebye V, Voutila J, Sinigaglia L, Meyer T, Pinato DJ, Sarker D, Basu B, Blagden S, Cook N, Jeffrey Evans TR, Yachnin J, Chee CE, Li D, El-Khoueiry A, Diab M, Huang KW, Pai M, Spalding D, Talbot T, Noel MS, Keenan B, Mahalingam D, Song MS, Grosso M, Arnaud D, Auguste A, Zacharoulis D, Storkholm J, McNeish I, Habib R, Rossi JJ, Habib NA. TIMEPOINT, a phase 1 study combining MTL-CEBPA with pembrolizumab, supports the immunomodulatory effect of MTL-CEBPA in solid tumors. Cell Rep Med. 2025;6:102041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Le TM, Pham KC. Comparative Evaluation of ASAP and GALAD Scores for Detecting Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Chronic Liver Diseases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2025;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Thanapirom K, Suksawatamnuay S, Thaimai P, Siripon N, Geratikornsupuk N, Treeprasertsuk S, Komolmit P. Comparison of the GALAD, GAAP, and ASAP Scores for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Detection in Patients With Chronic Liver Diseases. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2025;15:102607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Attia AM, Rezaee-Zavareh MS, Hwang SY, Kim N, Adetyan H, Yalda T, Chen PJ, Koltsova EK, Yang JD. Novel Biomarkers for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14:2278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Parikh ND, Mehta AS, Singal AG, Block T, Marrero JA, Lok AS. Biomarkers for the Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29:2495-2503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Chatzipanagiotou OP, Loukas C, Vailas M, Machairas N, Kykalos S, Charalampopoulos G, Filippiadis D, Felekouras E, Schizas D. Artificial intelligence in hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis: a comprehensive review of current literature. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;39:1994-2005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/