Published online Feb 14, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i6.115232

Revised: November 17, 2025

Accepted: December 15, 2025

Published online: February 14, 2026

Processing time: 113 Days and 23.5 Hours

A close bidirectional regulatory network exists between endocrine disorders and liver dysfunction, and their reciprocal imbalance is a key driver of metabolic liver diseases and chronic liver diseases. Based on the review, this letter systematically appraises its value in elucidating bidirectional crosstalk mechanisms across the thyroid, parathyroid, pancreas, adrenal, and sex hormone axes with the liver, while identifying limitations in mechanistic depth and clinical translation. Ali

Core Tip: The endocrine system and liver form a dynamic bidirectional network via hormone synthesis/metabolism and signaling regulation. Hormones (e.g., thyroid hormones, insulin) maintain hepatic glucose/lipid homeostasis and bile acid metabolism; conversely, chronic liver diseases disrupt endocrine balance through impaired hormone clearance, hypo

- Citation: Wan KR, Qian C, Liu LM. Bidirectional regulation between the endocrine system and liver: From mechanisms to multidisciplinary clinical care. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(6): 115232

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i6/115232.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i6.115232

We have read with great interest the review published by Vargas-Beltran et al[1]. Centered on the interplay between the endocrine system and liver function, this review systematically summarizes the pathophysiological links between multiple endocrine axes (thyroid, parathyroid, pancreas, adrenal glands, and sex hormones) and liver diseases, offering substantial academic value and clinical relevance.

The review’s notable contributions are threefold. First, it delineates the mechanisms of liver injury induced by common clinical endocrine abnormalities, including lipid metabolism disorders, oxidative stress activation, and impaired hormone conversion; second, it outlines the application prospects of emerging drugs such as thyroid hormone receptor β (THRβ) agonists and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists; third, it breaks from the traditional “single-organ di

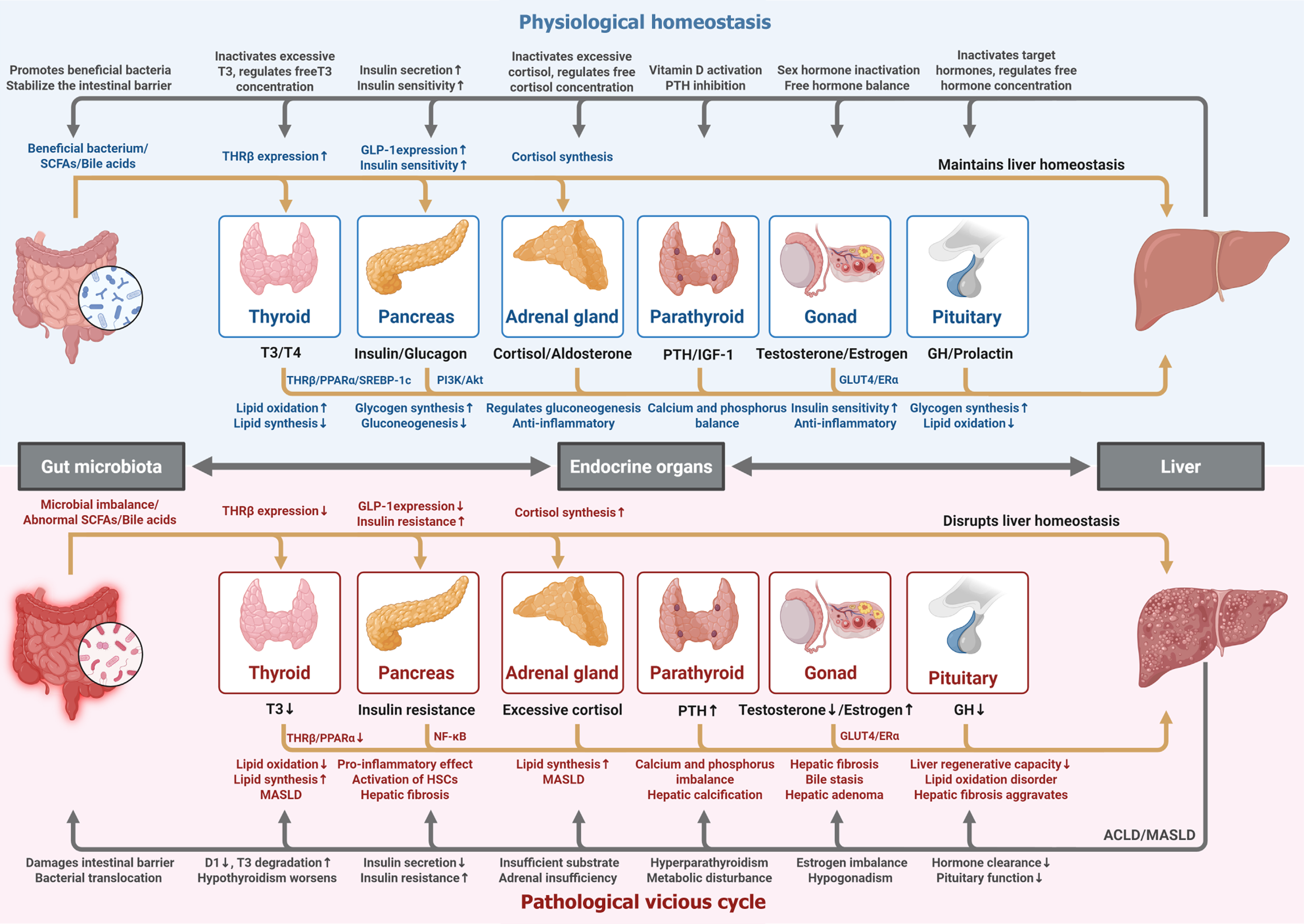

Under physiological and pathological conditions, there exists a dynamic bidirectional regulatory network between endocrine organs (thyroid gland, parathyroid gland, pancreas, adrenal glands, gonads) and the liver, with the gut microbiota participating in regulating this cyclic process (Figure 1). In the physiological state, the gut microbiota regulates the body’s endocrine function through its metabolites and synergizes with endocrine hormone secretion to maintain hepatic homeostasis. In the pathological state, gut microbiota dysbiosis and endocrine disorders (e.g., insulin resistance, hypothyroidism) induce hepatic injury through pro-inflammatory and fibrogenic pathways, while liver dysfunction in turn impairs hormone clearance and gut barrier integrity, thereby exacerbating systemic imbalance and forming a path

To address the aforementioned limitations and align with current research priorities, we propose targeted exploration in the following directions.

Future studies should dissect how endocrine hormones regulate hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) activation and hepatocyte death programs at the molecular level. For instance, aldosterone binds to mineralocorticoid receptors in HSCs, activating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase-dependent reactive oxygen species production and Rho-associated kinase signaling, driving HSCs activation and extracellular matrix synthesis. In contrast, insulin resistance and glucocorticoid excess can augment hepatocyte pyroptosis through the NOD-like receptor pyrin domain-containing protein 3-caspase-1-gasdermin D pathway. Clarifying these context-dependent circuits will identify liver-specific targets for pre

Leverage metabolomics and proteomics to screen for specific biomarker panels (e.g., FGF21 + fetuin-A + bile acid derivatives), construct machine learning-based disease risk prediction models, and analyze prognostic differences across endocrine subtypes of liver disease via big data, enabling precise staging and dynamic monitoring.

Design prospective studies for pregnant women, older adults, and children to delineate age- and pregnancy-related differences in endocrine-liver crosstalk, drug pharmacokinetics, and safety profiles. Based on these data, develop indi

Explore the regulatory effects of gut microbiota on endocrine hormone metabolism via fecal microbiota transplantation, probiotic intervention, and metabolite supplementation, laying the groundwork for combined regimens of “microbial agents + endocrine-targeted therapy”.

Evaluate the clinical value of endocrine-liver MDT based on multi-center real-world data, focusing on endpoints such as liver fibrosis reversal, endocrine disorder remission, and mortality, to provide evidence for updating clinical practice guidelines.

In conclusion, this review establishes a solid foundation for interdisciplinary research in endocrinology and hepatology. Its emphasis on bidirectional regulation and MDT collaboration holds clear clinical implications. Future research should address the identified gaps by refining molecular mechanisms, expanding special population data, and integrating emerging evidence. These efforts will advance the theoretical system of endocrine-liver crosstalk and shift the mana

We thank all reviewers for their constructive comments, which significantly improved the manuscript.

| 1. | Vargas-Beltran AM, Armendariz-Pineda SM, Martínez-Sánchez FD, Martinez-Perez C, Torre A, Cordova-Gallardo J. Interplay between endocrine disorders and liver dysfunction: Mechanisms of damage and therapeutic approaches. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:108827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Hsu CL, Schnabl B. The gut-liver axis and gut microbiota in health and liver disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:719-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 127.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhang Y, Wang X, Lin J, Liu J, Wang K, Nie Q, Ye C, Sun L, Ma Y, Qu R, Mao Y, Zhang X, Lu H, Xia P, Zhao D, Wang G, Zhang Z, Fu W, Jiang C, Pang Y. A microbial metabolite inhibits the HIF-2α-ceramide pathway to mediate the beneficial effects of time-restricted feeding on MASH. Cell Metab. 2024;36:1823-1838.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wong R, Yuan LY. Sarcopenia and metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease: Time to address both. World J Hepatol. 2024;16:871-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Goldner D, Lavine JE. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children: Unique Considerations and Challenges. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1967-1983.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sarkar M, Kushner T. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and pregnancy. J Clin Invest. 2025;135:e186426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Harrison SA, Bedossa P, Guy CD, Schattenberg JM, Loomba R, Taub R, Labriola D, Moussa SE, Neff GW, Rinella ME, Anstee QM, Abdelmalek MF, Younossi Z, Baum SJ, Francque S, Charlton MR, Newsome PN, Lanthier N, Schiefke I, Mangia A, Pericàs JM, Patil R, Sanyal AJ, Noureddin M, Bansal MB, Alkhouri N, Castera L, Rudraraju M, Ratziu V; MAESTRO-NASH Investigators. A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:497-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 840] [Cited by in RCA: 1103] [Article Influence: 551.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sanyal AJ, Newsome PN, Kliers I, Østergaard LH, Long MT, Kjær MS, Cali AMG, Bugianesi E, Rinella ME, Roden M, Ratziu V; ESSENCE Study Group. Phase 3 Trial of Semaglutide in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:2089-2099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 298.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Geng L, Lam KSL, Xu A. The therapeutic potential of FGF21 in metabolic diseases: from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:654-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 433] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stefan N, Schick F, Birkenfeld AL, Häring HU, White MF. The role of hepatokines in NAFLD. Cell Metab. 2023;35:236-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 63.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vidal-Cevallos P, Murúa-Beltrán Gall S, Uribe M, Chávez-Tapia NC. Understanding the Relationship between Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Thyroid Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:14605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cao X, Wang N, Yang M, Zhang C. Lipid Accumulation and Insulin Resistance: Bridging Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease and Chronic Kidney Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:6962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/