Published online Feb 14, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i6.115556

Revised: November 17, 2025

Accepted: December 22, 2025

Published online: February 14, 2026

Processing time: 104 Days and 20.6 Hours

Peritoneal metastasis influences prognosis and quality of life in patients with gastric cancer. The efficacy of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) as postoperative adjuvant therapy for advanced gastric cancer remains unclear.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of HIPEC plus postoperative adjuvant chemo

We analyzed 225 patients with gastric cancer who underwent radical surgery, categorized by those receiving HIPEC plus AC (HIPEC + AC group) and those receiving AC alone (AC group). Treatments were administered every other day, for a total of one to three sessions. Overall survival, disease-free survival (DFS), disease-free interval, peritoneal metastasis-free interval, and safety outcomes were compared between the groups. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank tests for group comparisons.

In total, 225 patients with non-metastatic pathological T staging 4 gastric adeno

HIPEC plus postoperative AC improves DFS and reduces peritoneal metastasis risk in non-metastatic pathological T staging 4 gastric adenocarcinoma without increasing adverse events, confirming its safety and efficacy in pre

Core Tip: The efficacy of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) as a postoperative adjuvant therapy for locally advanced gastric cancer remains unclear. This study analyzed 225 patients with nonmetastatic pathological T staging 4 gastric adenocarcinoma and found that HIPEC plus adjuvant chemotherapy significantly improved disease-free survival and reduced the risk of peritoneal metastasis without additional adverse reactions in non-metastatic pathological T staging 4 gastric adenocarcinoma. These results establish HIPEC as a safe and effective adjuvant therapy for preventing postoperative recurrence and peritoneal dissemination.

- Citation: Lian WL, Cai LS, Lian MQ, Lian MJ, Sun YQ, Lv CB, Huang GP, Huang RJ, Zhang YB, Zeng WM, Xu QH, Zhu QJ, Chen QX. Efficacy and safety of sequential hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy following surgery for pathological T staging 4 gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(6): 115556

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i6/115556.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i6.115556

Gastric cancer is the fifth most prevalent malignancy worldwide and a leading cause of cancer-related mortality, accounting for 4.8% of all cancer cases and 6.8% of cancer-related deaths. This disease has particularly high incidence rates in East Asian regions, including China and Japan[1]. Peritoneal metastasis is a frequent and aggressive progression pathway in gastric cancer and is associated with dismal clinical outcomes. Current evidence suggests that 10%-21% of patients with gastric cancer develop peritoneal metastases, with median survival typically limited to 4-6 months[2,3]. These metastases not only drastically shorten patient survival but also frequently cause debilitating complications, including ascites, intestinal obstruction, and cachexia, severely compromising the quality of life. The effective prevention of peritoneal metastasis following radical gastric cancer surgery represents a critical therapeutic challenge.

Conventional systemic chemotherapy has limited efficacy in preventing or treating peritoneal metastases because the peritoneum-plasma barrier restricts drug penetration, often resulting in poor outcomes in patients with gastric cancer[4,5]. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) delivers temperature-controlled chemotherapeutic agents directly into the abdominal cavity, increasing local drug concentrations and enhancing cytotoxic effects. As part of multimodal therapy, HIPEC has demonstrated clinical utility in managing peritoneal carcinomatosis and is increasingly incorporated into multicenter treatment protocols[6]. When administered after tumor resection, HIPEC augments chemotherapeutic cytotoxicity and improves the overall treatment efficacy[7]. In patients with established peritoneal cancer, the combination of HIPEC and cytoreductive surgery may allow some patients to achieve long-term survival[8]. HIPEC is also under investigation as a prophylactic intervention to prevent the peritoneal seeding of gastrointestinal cancers[9]. A 2021 study reported that prophylactic HIPEC after curative colon cancer resection may reduce peritoneal recurrence and improve disease-free survival (DFS)[10]. Additional research supports its potential in preventing postoperative peritoneal recurrence in gastric cancer[11]; however, large-scale randomized trials validating long-term efficacy and safety remain necessary. The clinical benefits of HIPEC vary owing to patient heterogeneity and tumor biology, with not all individuals experiencing significant improvements[12]. A 2019 systematic review of 11 studies comparing prophylactic HIPEC combined with surgery to surgery alone for gastric cancer suggested that HIPEC reduces peritoneal recurrence and improves survival outcomes while demonstrating safety and feasibility[13]. However, the included studies were characterized by methodological heterogeneity and partial obsolescence. Consequently, no international consensus has been reached regarding the role of HIPEC in the management of resectable gastric cancers[14].

To assess the efficacy and safety of HIPEC combined with curative gastrectomy, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients with locally advanced gastric cancer [pathological stage T4a-b/N0-3/non-metastatic (M0)] treated by a single surgical team at our institution. We compared the postoperative outcomes between patients receiving HIPEC plus adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) and those who received AC alone, focusing on median survival, overall survival (OS), DFS, disease-free interval (DFI), peritoneal metastasis-free interval (PMFI) and treatment-related adverse reactions.

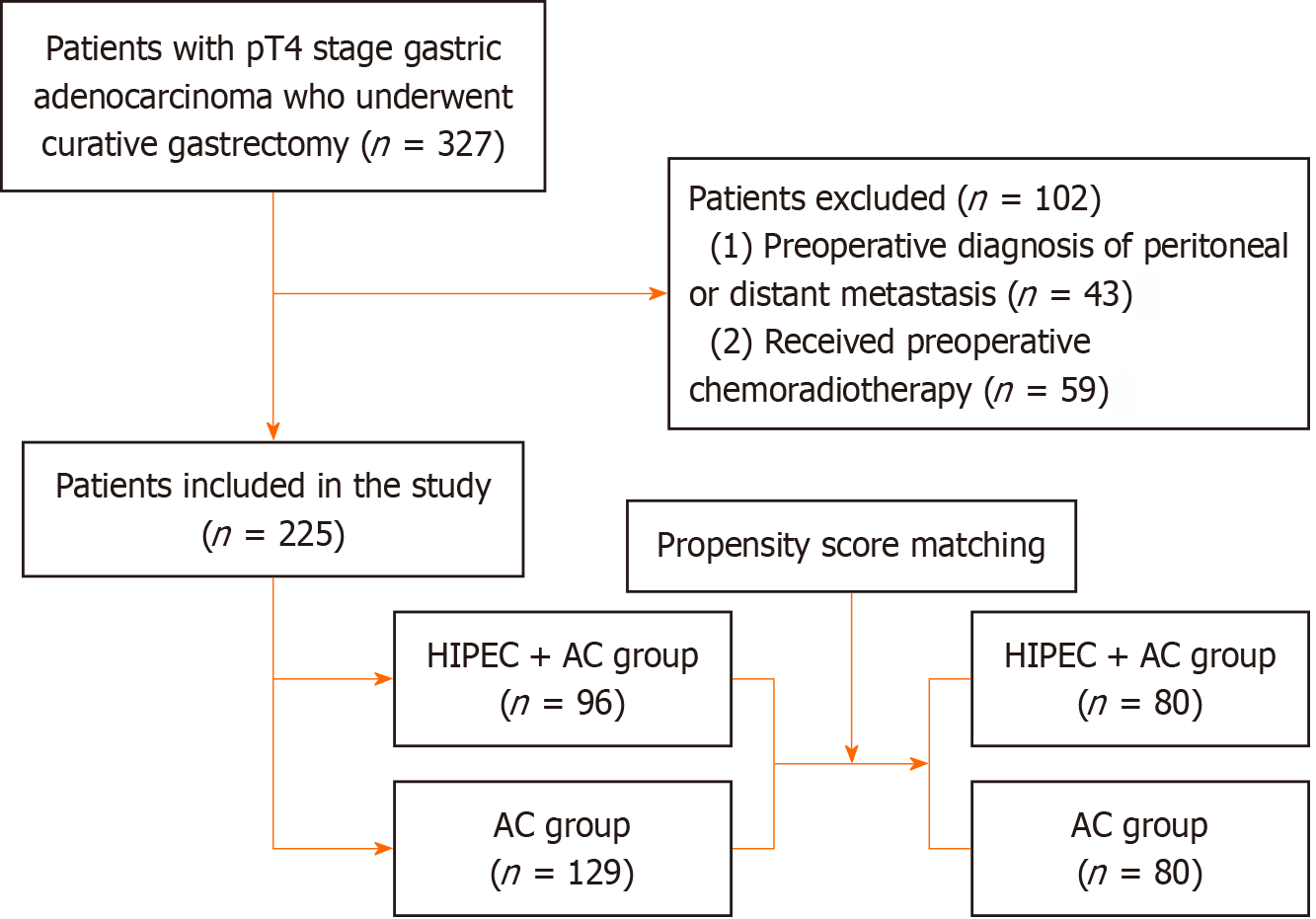

This study analyzed patients with M0 pathological T staging (pT) 4 stage gastric adenocarcinoma who underwent curative gastrectomy between March 2017 and September 2021. Based on historical treatment records, eligible patients were stratified into two groups: (1) The HIPEC + AC group received HIPEC combined with standard AC; and (2) The AC group received standard AC alone (Figure 1). Our retrospective protocol complied with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital (No. 2025 LWB196).

Patients were included if they met the following criteria: (1) Pathological diagnosis of locally advanced gastric cancer (T4a-b, N0-3, M0); (2) Treatment with radical gastrectomy; and (3) Postoperative administration of AC alone or in com

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Preoperative diagnosis of peritoneal or distant metastases; (2) Received preoperative chemoradiotherapy or other experimental therapies; (3) Contraindications to HIPEC or systemic chemo

Two patient cohorts underwent radical gastrectomy prior to treatment. Following the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines[15], the surgeons performed either total gastrectomy or distal gastrectomy with concomitant D2 Lymphadenectomy. Digestive tract reconstruction involved a Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy (or gastrojejunostomy) with Braun's anastomosis, when applicable.

The HIPEC + AC group underwent abdominal puncture tube placement 3-4 weeks postoperatively, connecting the infusion tube to the precise intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion treatment system (HGGZ-102intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion treatment machine), which continuously and stably injected and drained the abdominal cavity. The treatment was conducted at 43 ± 0.1 °C with a perfusion rate of 400-600 mL/minute. Each session lasted 60-90 minutes and used 5 L of perfusate. The chemotherapeutic agents added to the perfusate were either docetaxel (80 mg) or 5-fluorouracil (1 g), dissolved in the 5 L solution. Treatments were administered every other day, for a total of one to three sessions[16]. When patients maintained adequate physical condition and tolerance, standard chemotherapy was commenced 48 hours after HIPEC completion. By contrast, chemotherapy was initiated 3-4 weeks postoperatively in the AC group. Both groups received postoperative gastric cancer chemotherapy following the NCCN guidelines[17], primarily using5-fluorouracil-based regimens, including FOLFOX, SOX, or XELOX.

Median survival time was the time point at which the cumulative survival probability reached 50%. OS was defined as the time interval from treatment initiation to death from any cause. DFS was the duration from treatment commencement to first recurrence or death from any cause (whichever occurred first). DFI was measured from the date of surgery or treatment initiation until the first documented recurrence or metastasis. PMFI was measured from the date of surgery or treatment initiation until the first documented peritoneal metastasis, based on either imaging or histological evidence. Treatment-related adverse events were recorded. Tumor marker levels were assessed before and 1 month after treatment.

Adverse events monitored during HIPEC therapy included intra-abdominal infection, hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction, bowel perforation, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, poor appetite, and fatigue.

Systemic chemotherapeutic toxicities included hematological effects such as myelosuppression (neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia) and hepatorenal dysfunction, including elevated alanine or aspartate aminotransferase and creatinine levels.

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous variables, expressed as mean ± SD, were compared using Student's t-test, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and compared using χ² tests or Fisher's exact tests as appropriate. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank tests for group comparisons. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

After the exclusion criteria were applied, 225 patients with complete datasets were included, comprising 96 patients in the HIPEC + AC group and 129 patients in the AC group. A comparative analysis of the clinicopathological characteristics (Table 1) revealed statistically significant differences between the groups before propensity score matching (PSM) for age, tumor location, and pathological N staging (P < 0.05). No significant differences were found in sex, differentiation grade, or pT (P ≥ 0.05) (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||||

| HIPEC + AC group | AC group | P value | SMD | HIPEC + AC group | AC group | P value | SMD | |

| Sex | 0.060 | 0.587 | ||||||

| Male | 75 (78.12) | 86 (66.67) | -0.243 | 61 (76.25) | 58 (72.50) | -0.084 | ||

| Female | 21 (21.88) | 43 (33.33) | 0.243 | 19 (23.75) | 22 (27.50) | 0.084 | ||

| Age | 60.00 (53.00, 67.25) | 65.00 (58.00, 71.00) | < 0.001 | 0.479 | 61.50 (55.00, 69.00) | 65.00 (55.75, 70.00) | 0.299 | 0.126 |

| Body mass index | 21.63 ± 3.21 | 21.89 ± 3.21 | 0.550 | 0.081 | 21.76 ± 3.22 | 22.08 ± 3.34 | 0.546 | 0.094 |

| Tumor location | 0.022 | 0.884 | ||||||

| Upper | 27 (28.12) | 60 (46.51) | 0.369 | 25 (31.25) | 29 (36.25) | 0.104 | ||

| Middle | 23 (23.96) | 20 (15.50) | -0.234 | 19 (23.75) | 16 (20.00) | -0.094 | ||

| Lower | 45 (46.88) | 46 (35.66) | -0.234 | 35 (43.75) | 34 (42.50) | -0.025 | ||

| Anastomotic site | 1 (1.04) | 3 (2.33) | 0.085 | 1 (1.25) | 1 (1.25) | 0.000 | ||

| Tumor differentiation | 0.793 | 0.668 | ||||||

| High-grade | 78 (81.25) | 103 (79.84) | -0.035 | 66 (82.50) | 68 (85.00) | 0.070 | ||

| Low-grade | 18 (18.75) | 26 (20.16) | 0.035 | 14 (17.50) | 12 (15.00) | -0.070 | ||

| Pathological T staging | 0.897 | 0.755 | ||||||

| T4a | 89 (92.71) | 119 (92.25) | -0.017 | 74 (92.50) | 75 (93.75) | 0.052 | ||

| T4b | 7 (7.29) | 10 (7.75) | 0.017 | 6 (7.50) | 5 (6.25) | -0.052 | ||

| Pathological N staging | 0.038 | 0.598 | ||||||

| N0 | 9 (9.38) | 25 (19.38) | 0.253 | 9 (11.25) | 7 (8.75) | -0.088 | ||

| N+ | 87 (90.62) | 104 (80.62) | -0.253 | 71 (88.75) | 73 (91.25) | 0.088 | ||

Based on the clinical and pathological data described above, we performed 1:1 PSM, yielding 80 precisely matched pairs. After matching, the two patient groups showed no statistically significant differences in clinical or pathological characteristics (Table 1).

The HIPEC perfusate contained docetaxel 80 mg (83 patients) or 5-fluorouracil 1 g (13 patients). All AC regimens were fluorouracil-based and administered in combination with platinum-based agents (40 patients in the HIPEC + AC group vs 64 patients in the AC group), taxanes (22 patients in the HIPEC + AC group vs 50 patients in the AC group), platinum-taxane combinations (26 patients in the HIPEC + AC group vs 6 patients in the AC group), or camptothecins (8 patients in the HIPEC + AC group vs 9 in the AC group) (Table 2).

| HIPEC + AC group (n = 96) | AC group (n = 129) | |

| Chemotherapy agents for HIPEC | ||

| Docetaxel | 83 (86.46) | - |

| 5-fluorouracil | 13 (13.54) | - |

| AC regimen | ||

| Platinum-based agents | 40 (41.67) | 64 (49.61) |

| Taxanes | 22 (22.92) | 50 (38.76) |

| Platinum-taxane combinations | 26 (27.08) | 6 (4.65) |

| Camptothecins | 8 (8.33) | 9 (6.98) |

The safety analysis revealed comparable rates of myelosuppression (before PSM: 28.13% vs 34.11%, P = 0.339; after PSM: 30.00% vs 37.50%, P = 0.316) and liver function abnormalities (before PSM: 11.46% vs 12.40%, P = 0.829; after PSM: 12.50% vs 12.50%, P = 1.000) between the HIPEC + AC and AC groups. Renal function abnormalities occurred in one patient in the AC group but were absent in the HIPEC + AC cohort (Table 3).

| Before PSM | After PSM | |||||||

| HIPEC + AC group | AC group | χ2 | P value | HIPEC + AC group | AC group | χ2 | P value | |

| Myelosuppression | 0.912 | 0.339 | 1.006 | 0.316 | ||||

| Yes | 27 (28.13) | 44 (34.11) | 24 (30.00) | 30 (37.50) | ||||

| No | 69 (71.88) | 85 (65.89) | 56 (70.00) | 50 (62.50) | ||||

| Liver function abnormalities | 0.047 | 0.829 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 11 (11.46) | 16 (12.40) | 10 (12.50) | 10 (12.50) | ||||

| No | 85 (88.54) | 113 (87.60) | 70 (87.50) | 70 (87.50) | ||||

Intra-abdominal infection developed in five patients (5.21%) in the HIPEC + AC group, while one patient (1.04%) experienced intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Five patients (5.21%) reported abdominal pain, and 23 (23.96%) experienced nausea and vomiting. Three patients (3.13%) presented with diarrhea, 3 (3.13%) reported poor appetite and fatigue, and 3 (3.13%) developed intestinal obstruction. No bowel perforations resulted from the peritoneal catheter placement (Table 4).

| Number | Percentage (%) | |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 5 | 5.21 |

| Intra-abdominal hemorrhage | 1 | 1.04 |

| Abdominal pain | 5 | 5.21 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 23 | 23.96 |

| Diarrhea | 3 | 3.13 |

| Poor appetite and fatigue | 3 | 3.13 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 3 | 3.13 |

After PSM, the AC group showed a median follow-up period of 56.00 ± 4.61 months, while the HIPEC + AC group exhibited a longer follow-up duration of 68.00 ± 4.99 months. At the final follow-up, the HIPEC + AC group maintained a cumulative survival rate above 50%, with the median survival time remaining unreached, whereas the AC group demonstrated a median survival of 50 months.

Prior to PSM, the HIPEC + AC group exhibited higher OS rates than the AC group at 1 year (95.00% vs 91.00%), 2 years (82.00% vs 78.00%), and 3 years (74.00% vs 65.00%), although these differences were not statistically significant [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.755, 95%CI: 0.502-1.136, P = 0.174; Supplementary Figure 1A]. DFS was significantly longer in the HIPEC + AC group at 1 year (91.00% vs 79.00%), 2 years (72.00% vs 62.00%), and 3 years (68.00% vs 51.00%) than in the AC group (HR = 0.681, 95%CI: 0.467-0.994, P = 0.043; Supplementary Figure 1B). DFI was significantly longer in the HIPEC + AC cohort than in the AC controls (HR = 0.652, 95%CI: 0.423-1.003, P = 0.048; Supplementary Figure 1C). Similarly, PMFI demonstrated a statistically significant prolongation following HIPEC + AC treatment (HR = 0.540, 95%CI: 0.318-0.919, P = 0.020; Supplementary Figure 1D).

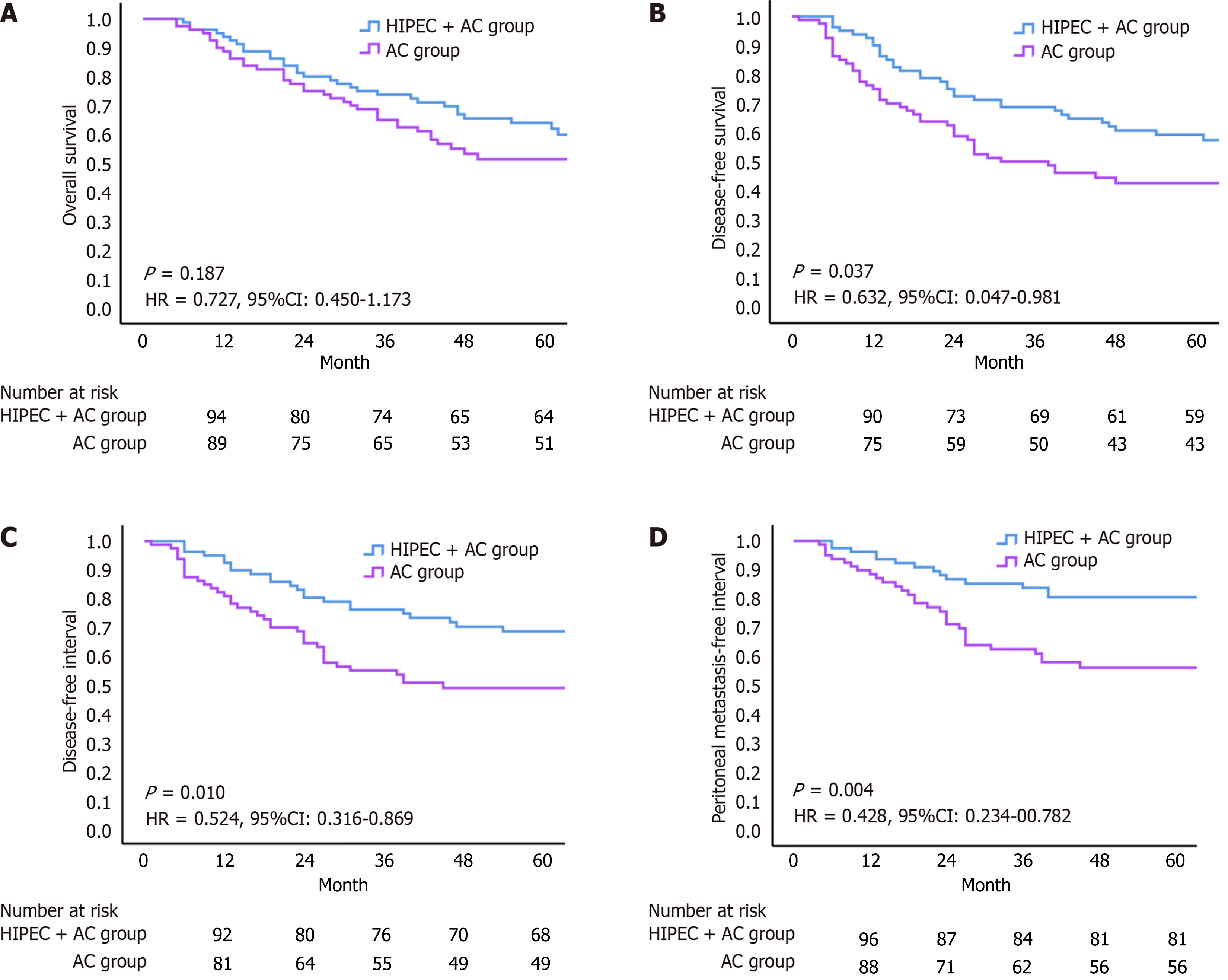

Following PSM, the HIPEC + AC group demonstrated higher OS rates than the AC group at 1 year (94.00% vs 89.00%), 2 years (80.00% vs 75.00%), and 3 years (74.00% vs 65.00%), although this difference was not statistically significant (HR = 0.727, 95%CI: 0.450-1.173, P = 0.187; Figure 2A). DFS was significantly longer in the HIPEC + AC group at all time points: 1 year (90.00% vs 75.00%), 2 years (73.00% vs 59.00%), and 3 years (69.00% vs 50.00%), with statistically significant differences (HR = 0.632, 95%CI: 0.047-0.981, P = 0.037; Figure 2B). DFI was also markedly extended in the HIPEC + AC group compared with that in the controls (HR = 0.524, 95%CI: 0.316-0.869, P = 0.010; Figure 2C). Similarly, the PMFI showed a statistically significant prolongation following HIPEC + AC treatment (HR = 0.428, 95%CI: 0.234-00.782, P = 0.004; Figure 2D).

To further evaluate the efficacy of HIPEC in the context of different systemic chemotherapy regimens, we conducted two subgroup analyses. First, in patients who received the potent "platinum-taxane combination regimen", the HIPEC + AC group demonstrated significantly superior OS, DFS, DFI, and PMFI vs the AC group (Supplementary Figure 2). Second, in the subgroup of patients who received the most commonly used SOX (tegafur, gimeracil, and oxaliplatin) or XELOX (capecitabine and oxaliplatin) regimens, the HIPEC + AC group also showed consistent trends toward better outcomes in terms of OS, DFS, DFI, and PMFI (Supplementary Figure 3). The differences in the latter subgroup did not reach statistical significance, potentially due to the limited sample size; nevertheless, both analyses consistently suggested that HIPEC provided an additional survival benefit when combined with systemic chemotherapy, regardless of the regimen intensity.

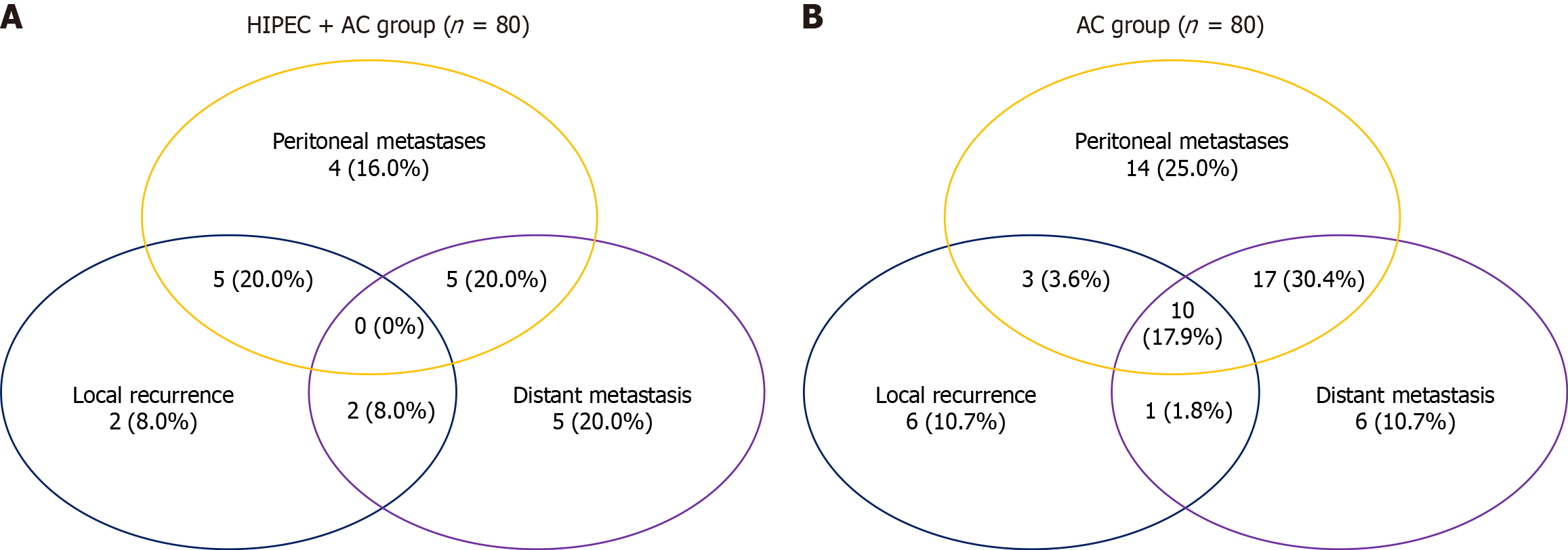

At the final follow-up, the recurrence patterns in the HIPEC + AC group included peritoneal metastasis (n = 20; 20.83%), local recurrence (n = 11; 10.46%), and distant metastasis (n = 19; 19.79%) (Supplementary Figure 4A). Correspondingly, patients in the AC group developed peritoneal metastases (n = 43, 33.33%), local recurrence (n = 19, 14.73%), and distant metastases (n = 29, 27.13%) (Supplementary Figure 4B). The peritoneal metastasis rate was significantly lower in the HIPEC + AC group than in the AC group (20.83% vs 33.33%, P = 0.039).

Following PSM, the HIPEC + AC group exhibited recurrence patterns consisting of peritoneal metastasis (n = 16, 20.00%), local recurrence (n = 9, 11.25%), and distant metastasis (n = 14, 17.50%) (Figure 3A). The AC group exhibited peritoneal metastasis (n = 31, 38.75%), local recurrence (n = 11, 13.75%), and distant metastasis (n = 22, 27.50%) (Figure 3B). Peritoneal metastasis rates were significantly lower in the HIPEC + AC group than in the AC group (20.00% vs 38.75%, P = 0.009).

This retrospective study evaluated patients with locally advanced gastric cancer (T4a-b, N0-3, M0) and compared postoperative HIPEC combined with AC with AC alone. The HIPEC + AC group demonstrated significantly prolonged DFS, DFI, and PMFI, along with lower peritoneal metastasis rates and greater reduction in tumor markers, compared with the AC group. No significant intergroup differences were observed in treatment-related adverse reactions. These findings suggest that combining HIPEC with AC improves disease control without substantially increasing toxicity.

HIPEC has emerged as a novel locoregional therapeutic approach, garnering increasing attention in recent clinical trials. A growing body of international evidence[18] demonstrates that combining HIPEC with standard systemic chemotherapy significantly improves the survival outcomes of patients with peritoneal metastatic disease. For instance, a large-scale multicenter randomized controlled trial confirmed that integrating HIPEC with postoperative systemic chemotherapy significantly prolonged DFS and OS compared with systemic chemotherapy alone[19]. Nevertheless, standardized treatment protocols for HIPEC remain undefined, and its clinical benefits in patients with resectable gastric cancer currently lack an international consensus.

HIPEC demonstrates an acceptable safety profile as adjuvant therapy for gastric cancer, with studies reporting no significant increase in adverse reactions[20-23]. These findings support its clinical application and facilitate further research. Currently, most HIPEC implementation methods involve intraoperative placement of perfusion catheters and intraoperative or early postoperative intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. However, given patients' compro

HIPEC has demonstrated survival benefits in multiple clinical studies[28-30]. Desiderio et al's meta-analysis[9] of 11 randomized and 21 non-randomized controlled trials (2520 patients) revealed significantly improved 3-year [relative risk (RR) = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.53-0.96, P = 0.03] and 5-year (RR = 0.82, 95%CI: 0.70-0.96, P = 0.01) OS rates compared with those in controls. In 2020, Xie et al[31] prospectively analyzed 113 patients with locally advanced gastric cancer and compared AC alone with AC combined with prophylactic HIPEC after curative gastrectomy. The control group showed 1-year and 3-year DFS rates of 91.9% and 60.4%, respectively, whereas the HIPEC group showed rates of 92.1% and 63.0%, respectively (P = 0.037). OS rates reached 95.2% and 66.3% in controls compared with 96.1% and 68.6% in the HIPEC group at 1 year and 3 years, respectively (P = 0.044), suggesting that postoperative HIPEC decreases peritoneal metastasis and improves survival in these patients. However, some studies reported no significant improvement in recurrence-free survival (84.8% vs 88.2%; P = 0.986)[22] or OS (41.1% vs 34.5%; P = 0.118)[32] with HIPEC.

In this study, OS did not differ significantly between the HIPEC + AC and AC groups, with P values of 0.174 and 0.187 before and after PSM (both P > 0.05). This finding may be due to several factors. OS depends on multiple determinants, such as intra-abdominal disease control, distant metastasis progression, patient heterogeneity, performance status, and postoperative management[33-35]. The progression of PM also varies substantially according to tumor biology and individual patient characteristics. Although the HIPEC + AC regimen demonstrated superior local control and suppression of peritoneal metastasis, these benefits may have been offset by competing survival determinants, potentially explaining the absence of significant OS improvement.

The significant improvement in DFS and DFI represents a pivotal finding of this study. Before and after PSM, the HIPEC + AC group consistently showed better DFS and DFI outcomes than the AC group, aligning with existing evidence[32,36,37]. These results suggest that HIPEC substantially delays disease recurrence or progression. By delivering high-concentration chemotherapeutic agents directly into the peritoneal cavity, HIPEC eradicates free cancer cells and micro metastases, thereby reducing the risk of local recurrence[38,39]. The synergistic effect of hyperthermia potentiates chemotherapeutic efficacy through enhanced drug penetration and cytotoxicity within the abdominal cavity, ultimately prolonging DFS. Consequently, the observed advantages in DFS and DFI are attributable to the capacity of HIPEC for effective intraperitoneal tumor control.

Peritoneal metastasis in gastric cancer confers a poor prognosis, and systemic chemotherapy provides limited survival benefits. HIPEC may serve as an adjuvant therapy postoperatively to enhance survival rates and reduce peritoneal metastasis[8]. A meta-analysis confirmed the efficacy of HIPEC in preventing peritoneal metastasis (RR = 0.63, 95%CI: 0.45-0.88, P < 0.01)[9]; a 2020 prospective study reported 11 peritoneal recurrences with conventional chemotherapy compared with only 2 with HIPEC (P = 0.020)[31]. In this study, the PMFI emerged as one of the most significantly improved endpoints in the HIPEC + AC group. PSM minimized confounding variables, facilitating precise assessment of the effect of HIPEC on metastasis rates. The HIPEC + AC group exhibited consistently lower peritoneal metastasis rates than the AC group across all timepoints, demonstrating the therapeutic efficacy of HIPEC. Extended follow-up revealed sustained low metastasis rates in the HIPEC + AC group, suggesting durable prophylactic effects. As an adjuvant prophylactic modality following curative surgery, HIPEC effectively reduced peritoneal recurrence, a finding concordant with that of multiple studies[25]. The pronounced advantage of HIPEC in peritoneal control suggests a potential benefit for distinct patient subsets, particularly those at high risk of peritoneal metastasis.

The significant improvements in DFS, DFI, and PMFI demonstrates the efficacy of HIPEC in delaying recurrence and preventing peritoneal dissemination. When considering the OS data, the observed HR before and after PSM (0.755 and 0.727, respectively) consistently favored the HIPEC + AC group, with absolute improvements in the 3-year OS rates (74.0% vs 65.0%). While this difference did not cross the threshold of statistical significance within the limits of our study, the OS endpoint is influenced by a broader and more complex set of factors that extend beyond the initial management of intra-abdominal disease. The biological aggression of the primary tumor, pattern and management of distant metastases, and efficacy of subsequent lines of therapy after recurrence can modulate the ultimate survival outcome. Furthermore, in a cohort of patients with a median age > 60 years, competing risks from non-cancer-related mortality may also attenuate the observable OS difference. Therefore, the pronounced benefits in disease control and prevention of peritoneal recurrence establish HIPEC as a highly valuable adjuvant strategy, warranting further validation in larger prospective cohorts with extended follow-up.

Another significant finding of this study stems from the subgroup analyses. The results indicated that HIPEC provided an additional survival benefit, whether it was combined with the potent "platinum-taxane combination regimen" (being statistically significant) or the commonly used SOX/XELOX regimens (showing clear positive trends). This strongly suggests that the survival improvement associated with HIPEC is independent of the intensity of concomitant systemic chemotherapy and is likely attributable to its intrinsic efficacy in controlling intraperitoneal microscopic disease. The lack of statistical significance in the SOX/XELOX subgroup underscores the need for validation of its efficacy in larger cohorts receiving specific chemotherapy regimens.

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective design may introduce unknown confounding factors, and the non-randomized controlled approach could lead to patient selection bias. However, strict PSM was implemented to minimize these effects and strengthen the validity of the conclusions. Second, this was a single-center study with a relatively small sample size. However, all patients were drawn from the same treatment cohort and received standardized surgical and adjuvant therapies, minimizing variations in survival outcomes attributable to treatment heterogeneity. Extended follow-up duration and large-scale multicenter randomized controlled trials are warranted to validate these findings and optimize therapeutic strategies for patients with gastric cancer.

For patients with locally advanced gastric cancer (stage T4a-b/N0-3/M0), the combination of postoperative HIPEC and conventional AC may prolong DFS and prevent peritoneal metastasis without significantly increasing the incidence of treatment-related adverse reactions. This regimen provides a clinically meaningful value in the management of gastric cancer.

| 1. | Chhikara BS, Parang K. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: The trends projection analysis. Chem Biol Lett. 2023;10:451. |

| 2. | Rijken A, Lurvink RJ, Luyer MDP, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, van Erning FN, van Sandick JW, de Hingh IHJT. The Burden of Peritoneal Metastases from Gastric Cancer: A Systematic Review on the Incidence, Risk Factors and Survival. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhou C, Wang Y, Ji MH, Tong J, Yang JJ, Xia H. Predicting Peritoneal Metastasis of Gastric Cancer Patients Based on Machine Learning. Cancer Control. 2020;27:1073274820968900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kitayama J, Ishigami H, Yamaguchi H, Sakuma Y, Horie H, Hosoya Y, Lefor AK, Sata N. Treatment of patients with peritoneal metastases from gastric cancer. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2018;2:116-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rau B, Brandl A, Thuss-Patience P, Bergner F, Raue W, Arnold A, Horst D, Pratschke J, Biebl M. The efficacy of treatment options for patients with gastric cancer and peritoneal metastasis. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22:1226-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Martins M, Santos-Sousa H, Araújo F, Nogueiro J, Sousa-Pinto B. Impact of Cytoreductive Surgery with Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Gastric Cancer with Peritoneal Carcinomatosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29:7528-7537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Helderman RFCPA, Löke DR, Kok HP, Oei AL, Tanis PJ, Franken NAPK, Crezee J. Variation in Clinical Application of Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy: A Review. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Seshadri RA, Glehen O. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1114-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Desiderio J, Chao J, Melstrom L, Warner S, Tozzi F, Fong Y, Parisi A, Woo Y. The 30-year experience-A meta-analysis of randomised and high-quality non-randomised studies of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the treatment of gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2017;79:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li T, Yu J, Chen Y, Liu R, Li Y, Wang YX, Wang JJ, Zhu P. Preventive intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion chemotherapy for patients with T4 stage colon adenocarcinoma. Tech Coloproctol. 2021;25:683-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhu L, Xu Z, Wu Y, Liu P, Qian J, Yu S, Xia B, Lai J, Ma S, Wu Z. Prophylactic chemotherapeutic hyperthermic intraperitoneal perfusion reduces peritoneal metastasis in gastric cancer: a retrospective clinical study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ceelen W, Demuytere J, de Hingh I. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy: A Critical Review. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:3114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Brenkman HJF, Päeva M, van Hillegersberg R, Ruurda JP, Haj Mohammad N. Prophylactic Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) for Gastric Cancer-A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tonello M, Cenzi C, Pizzolato E, Martini M, Pilati P, Sommariva A. National Guidelines for Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) in Peritoneal Malignancies: A Worldwide Systematic Review and Recommendations of Strength Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2025;32:5795-5806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1575] [Cited by in RCA: 1953] [Article Influence: 217.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Zhang T, Pan Q, Xiao S, Li L, Xue M. Docetaxel combined with intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion chemotherapy and hyperthermia in the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3287-3292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Almhanna K, Bentrem DJ, Chao J, Das P, Denlinger CS, Fanta P, Farjah F, Fuchs CS, Gerdes H, Gibson M, Glasgow RE, Hayman JA, Hochwald S, Hofstetter WL, Ilson DH, Jaroszewski D, Johung KL, Keswani RN, Kleinberg LR, Korn WM, Leong S, Linn C, Lockhart AC, Ly QP, Mulcahy MF, Orringer MB, Perry KA, Poultsides GA, Scott WJ, Strong VE, Washington MK, Weksler B, Willett CG, Wright CD, Zelman D, McMillian N, Sundar H. Gastric Cancer, Version 3.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:1286-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 640] [Cited by in RCA: 689] [Article Influence: 68.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chen Y, Zhou Y, Xiong H, Wei Z, Zhang D, Li S. Exploring the Efficacy of Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Perfusion Chemotherapy in Gastric Cancer: Meta-analysis Based on Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann Surg Oncol. 2025;32:240-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, van Sloothen GW, van Tinteren H, Boot H, Zoetmulder FA. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3737-3743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1396] [Cited by in RCA: 1542] [Article Influence: 67.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Reutovich MY, Krasko OV, Sukonko OG. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in serosa-invasive gastric cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45:2405-2411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rau B, Lang H, Koenigsrainer A, Gockel I, Rau HG, Seeliger H, Lerchenmueller C, Reim D, Wahba R, Angele M, Heeg S, Keck T, Weimann A, Topp S, Piso P, Brandl A, Schuele S, Jo P, Pratschke J, Wegel S, Rehders A, Moosmann N, Gaedcke J, Heinemann V, Trips E, Loeffler M, Schlag PM, Thuss-Patience P. Effect of Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy on Cytoreductive Surgery in Gastric Cancer With Synchronous Peritoneal Metastases: The Phase III GASTRIPEC-I Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:146-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fan B, Bu Z, Zhang J, Zong X, Ji X, Fu T, Jia Z, Zhang Y, Wu X. Phase II trial of prophylactic hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer after curative surgery. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu YW, Du Y, Chen BA. Effect of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for gastric cancer patients: a meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials. J Int Med Res. 2019;47:5926-5936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Karimi M, Shirsalimi N, Sedighi E. Challenges following CRS and HIPEC surgery in cancer patients with peritoneal metastasis: a comprehensive review of clinical outcomes. Front Surg. 2024;11:1498529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhu L, Xu Y, Shan Y, Zheng R, Wu Z, Ma S. Intraperitoneal perfusion chemotherapy and whole abdominal hyperthermia using external radiofrequency following radical D2 resection for treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36:403-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ni X, Wu P, Wu J, Ji M, Tian B, Jiang Z, Sun Y, Xing X, Jiang J, Wu C. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal perfusion chemotherapy and response evaluation in patients with gastric cancer and malignant ascites. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:1691-1696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ba M, Cui S, Long H, Gong Y, Wu Y, Lin K, Tu Y, Zhang B, Wu W. Safety and Effectiveness of High-Precision Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Perfusion Chemotherapy in Peritoneal Carcinomatosis: A Real-World Study. Front Oncol. 2021;11:674915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ji ZH, Zhao QD, Li Y. The Effects of HIPEC on Survival of Gastric Cancer Patients With Peritoneal Metastasis. J Surg Oncol. 2024;130:1190-1195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhang JF, Lv L, Zhao S, Zhou Q, Jiang CG. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) Combined with Surgery: A 12-Year Meta-Analysis of this Promising Treatment Strategy for Advanced Gastric Cancer at Different Stages. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29:3170-3186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Patel M, Arora A, Mukherjee D, Mukherjee S. Effect of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy on survival and recurrence rates in advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2023;109:2435-2450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Xie TY, Wu D, Li S, Qiu ZY, Song QY, Guan D, Wang LP, Li XG, Duan F, Wang XX. Role of prophylactic hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;12:782-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Zhong Y, Kang W, Hu H, Li W, Zhang J, Tian Y. Lobaplatin-based prophylactic hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for T4 gastric cancer patients: A retrospective clinical study. Front Oncol. 2023;13:995618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Riggs MJ, Pandalai PK, Kim J, Dietrich CS. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Engbersen MP, Aalbers AGJ, Van't Sant-Jansen I, Velsing JDR, Lambregts DMJ, Beets-Tan RGH, Kok NFM, Lahaye MJ. Extent of Peritoneal Metastases on Preoperative DW-MRI is Predictive of Disease-Free and Overall Survival for CRS/HIPEC Candidates with Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:3516-3524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhao PY, Hu SD, Li YX, Yao RQ, Ren C, He CZ, Li SY, Wang YF, Yao YM, Huang XH, Du XH. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Colorectal Cancer Patients at High Risk of Peritoneal Carcinomatosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Surg. 2020;7:590452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Liu L, Sun L, Zhang N, Liao CG, Su H, Min J, Song Y, Yang X, Huang X, Chen D, Chen Y, Zhang HW, Zhang H. A novel method of bedside hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy as adjuvant therapy for stage-III gastric cancer. Int J Hyperthermia. 2022;39:239-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Reutovich MY, Krasko OV, Sukonko OG. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in prevention of gastric cancer metachronous peritoneal metastases: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12:S5-S17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zhang J, Mei L, Wang F, Li Y. Ten years' disease-free survival of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer treated by cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e23404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | El Hajj H, Vanseymortier M, Hudry D, Bogart E, Abdeddaim C, Leblanc E, Le Deley MC, Narducci F. Rationale and study design of the CHIPPI-1808 trial: a phase III randomized clinical trial evaluating hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for stage III ovarian cancer patients treated with primary or interval cytoreductive surgery. ESMO Open. 2021;6:100098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/