Published online Feb 14, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i6.113195

Revised: November 7, 2025

Accepted: December 22, 2025

Published online: February 14, 2026

Processing time: 142 Days and 23.8 Hours

The global burden of primary liver cancer (PLC) continues to rise. Although minimally invasive, especially laparoscopic, resection is increasingly performed for early-stage disease, 1-year adverse outcomes (recurrence, metastasis, or mortality) remain common. Widely used scores, such as the albumin-bilirubin grade, primarily assess hepatic reserve and may not fully reflect tumor biology or systemic inflammation for individualized early prognostic warning. This study aimed to develop and validate a least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO)-based model to predict 1-year adverse outcomes after minimally inva

To identify predictors of short-term (1-year) adverse outcomes following minima

This retrospective study included patients with PLC who underwent minimally invasive resection at The Affiliated Suqian Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University between January 2019 and January 2023. Prognostic predictors were identified using LASSO regression and incorporated into a logistic regression model. Model performance and clinical utility were evaluated using receiver operating characteristic curves, calibration plots, and decision curve analysis. The dataset was randomly divided into training (n = 277) and internal validation (n = 144) cohorts. An external validation cohort of 138 patients with PLC (February 2023 to June 2024) was used to assess generalizability.

Receiver operating characteristic analysis indicated good performance of the logistic regression model based on six predictors, white blood cell count, tumor diameter, vascular invasion, portal vein infiltration, cirrhosis, and alpha-fetoprotein, with area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.756 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.687-0.824] and 0.750 (95%CI: 0.659-0.841) in the training and internal validation cohorts, respectively. The model exhibited strong calibration (training, P = 0.6951; external validation, P = 0.5223) and clear net clinical benefit across risk thresholds. External validation further supported its generalizability (n = 138; AUC = 0.735, 95%CI: 0.640-0.830). Compared with albumin-bilirubin, the LASSO-based risk score showed higher though non-significant AUCs in the training (0.756 vs 0.691; DeLong P = 0.206) and external (0.735 vs 0.717; P = 0.803) cohorts and comparable performance in the internal validation cohort (0.750 vs 0.753; P = 0.968).

LASSO regression was used to identify six independent predictors of adverse 1-year outcomes after minimally invasive PLC resection. The resulting risk score model demonstrates reliable discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility for individualized prognostic assessment.

Core Tip: Preoperatively assess white blood cell count, alpha-fetoprotein, and liver function; evaluate tumor size and vascular or portal vein invasion through imaging; document cirrhosis status. Apply the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator-based model to calculate individualized 1-year risk and guide tailored postoperative follow-up. High-risk patients should undergo multidisciplinary team review and early intervention. Combine risk score output with albumin-bilirubin scoring to assess hepatic reserve, continuously refining thresholds to enhance accuracy, generalizability, and clinical utility. This integrative approach enables early identification of recurrence risk and supports precision management after minimally invasive resection for hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Citation: Feng W, Ye QW, Wang QL, Chen SY, Ma Y, Meng FL. Predictors of one-year adverse outcomes after laparoscopic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: Development and validation of an early-warning model. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(6): 113195

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i6/113195.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i6.113195

Globally, primary liver cancer (PLC) ranks as the sixth most common malignancy and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality[1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma account for 75%-85% and 10%-15% of cases, respectively, while combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma remains rare[2]. Men are more susceptible to liver cancer (LC) and show higher mortality rates. The global incidence continues to rise, with over 1 million cases projected by 2025, more than 70% in Asia and approximately 50%in China, posing a major public health challenge[3,4].

LC onset is often insidious, with nonspecific early symptoms, leading most patients to present at intermediate or advanced stages. Early screening of high-risk groups and effective prevention are thus critical to reducing mortality and improving survival[5]. The primary risk factors include hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, especially prevalent in East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In China about 90% of LC patients are infected with HBV, and 85%-90% exhibits cirrhosis[6,7]. Hepatitis C virus infection also contributes substantially to LC development[8].

For early-stage LC, first-line curative options include partial hepatectomy, liver transplantation, and local ablation[9]. Given limited donor availability, radical resection remains preferred. Minimally invasive approaches, laparoscopic or robot-assisted, are increasingly adopted for LC, offering reduced trauma, faster recovery, and fewer complications, thereby improving quality of life and postoperative recovery[10]. However, postoperative recurrence remains high (60%-80%), significantly affecting long-term prognosis. Recurrence is categorized as early (< 2 years) or late (> 2 years), attributed respectively to micrometastasis of the primary lesion or new tumor formation within the altered tumor mi

Accurate prognostic assessment is vital for LC management, as it supports individualized treatment, postoperative optimization, and better outcomes[12]. Logistic and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression are commonly used to construct predictive models integrating clinical, laboratory, and imaging parameters. LASSO’s efficient variable selection enhances model accuracy and simplicity, explaining its wide use in complex disease modeling[13]. However, few studies have examined short-term (1-year) prognosis in stage I-II LC after minimally invasive resection. Existing studies are limited by small sample sizes and insufficient external validation, constraining model generalizability.

This study aimed to identify risk factors for poor short-term prognosis in patients with PLC undergoing minimally invasive resection and to develop an individualized LASSO-based warning model for postoperative outcome prediction. Its novelty lies in focusing on minimally invasive surgery, optimizing variable selection through LASSO, ensuring stability and practicability via training-validation comparisons, and constructing a clinically applicable nomogram. Accurate prognostic evaluation enables clinicians to identify high-risk patients early, implementing timely interventions, and adopt aggressive management strategies to reduce recurrence and improve survival.

This retrospective study aimed to identify the risk factors for poor 1-year prognosis after minimally invasive resection in patients with PLC and to construct an individualized warning model using LASSO regression.

Clinical data were obtained from the electronic medical record system of The Affiliated Suqian Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University. The study included patients with PLC who underwent minimally invasive resection between January 2019 and January 2023. An additional 138 patients with PLC treated between February 2023 and June 2024 were retrospectively included as the external validation cohort.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients met the diagnostic criteria in the Diagnosis and Treatment Specifications for Primary Liver Cancer (2017 Edition)[14], with disease stage I-II; (2) Postoperative pathology confirmed PLC (HCC); (3) All patients underwent laparoscopic surgery; (4) Child-Pugh grade A or B; and (5) Complete clinical and follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Received preoperative radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or other antitumor therapy; (2) Tumors invading adjacent organs or exhibiting distant metastasis; (3) Had dysfunction of vital organs (kidneys, heart, or lungs); (4) Had coagulation disorders; (5) Had concurrent malignancies; (6) Died during postoperative hospitalization; or (7) Underwent re-resection for recurrent LC.

Baseline clinical data were extracted from the hospital’s electronic medical records, including sex, smoking and alcohol history, hypertension, diabetes, HBV infection status, Child-Pugh classification[15], tumor diameter, tumor number, differentiation degree, vascular invasion, hepatic vein infiltration, portal vein infiltration, and cirrhosis status. Sex was categorized as male or female; smoking, alcohol use, hypertension, and diabetes as yes and no; and HBV infection as infected or uninfected. Child-Pugh class was recorded as grade A or B. Tumor diameter was classified as ≥ 5 cm or < 5 cm, tumor number as single or multiple, and differentiation degree as poor, moderate, or well. Vascular invasion, hepatic vein infiltration, portal vein infiltration, and cirrhosis were dichotomized as present/absent or cirrhosis/non-cirrhosis. Laboratory parameters included white blood cell count (WBC), platelet count (PLT), albumin (ALB), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TBIL), and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP; ≥ 400 μg/L vs < 400 μg/L, threshold: 400 μg/L). The ALB-bilirubin (ALBI) score was calculated using the standard formula: ALBI = [Log10TBIL (μmol/L) × 0.66] + [ALB (g/L) × (-0.085)].

Patient were grouped based on 1-year postoperative outcomes. The good prognosis group included those without recurrence, metastasis, or death within one year, whereas the poor-prognosis group included patients who experienced any of these events.

In this study, LASSO regression[16] was used for variable selection and regularization in the presence of numerous predictors by introducing an L1 penalty term. This penalty shrinks less significant coefficients toward zero, thereby isolating key prognostic factors. Such an approach reduces model complexity, minimizes overfitting, and enhances generalizability. During model construction, optimal λ values were determined using 10-fold cross-validation.

Descriptive statistics summarized patient baseline characteristics; continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range), and categorical variables as n (%). Intergroup differences (good vs poor prognosis) were analyzed using independent-samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U tests for continuous data and χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical data. LASSO regression, through its inherent penalty term, was employed to identify prognosis-related predictors, which were then entered into a logistic regression model to calculate poor-prognosis probabilities. Model performance was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), calibration curves, and decision curve analysis (DCA) to assess discrimination, accuracy, and clinical net benefit, respectively. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0, and visualization was conducted in R version 4.1.3. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

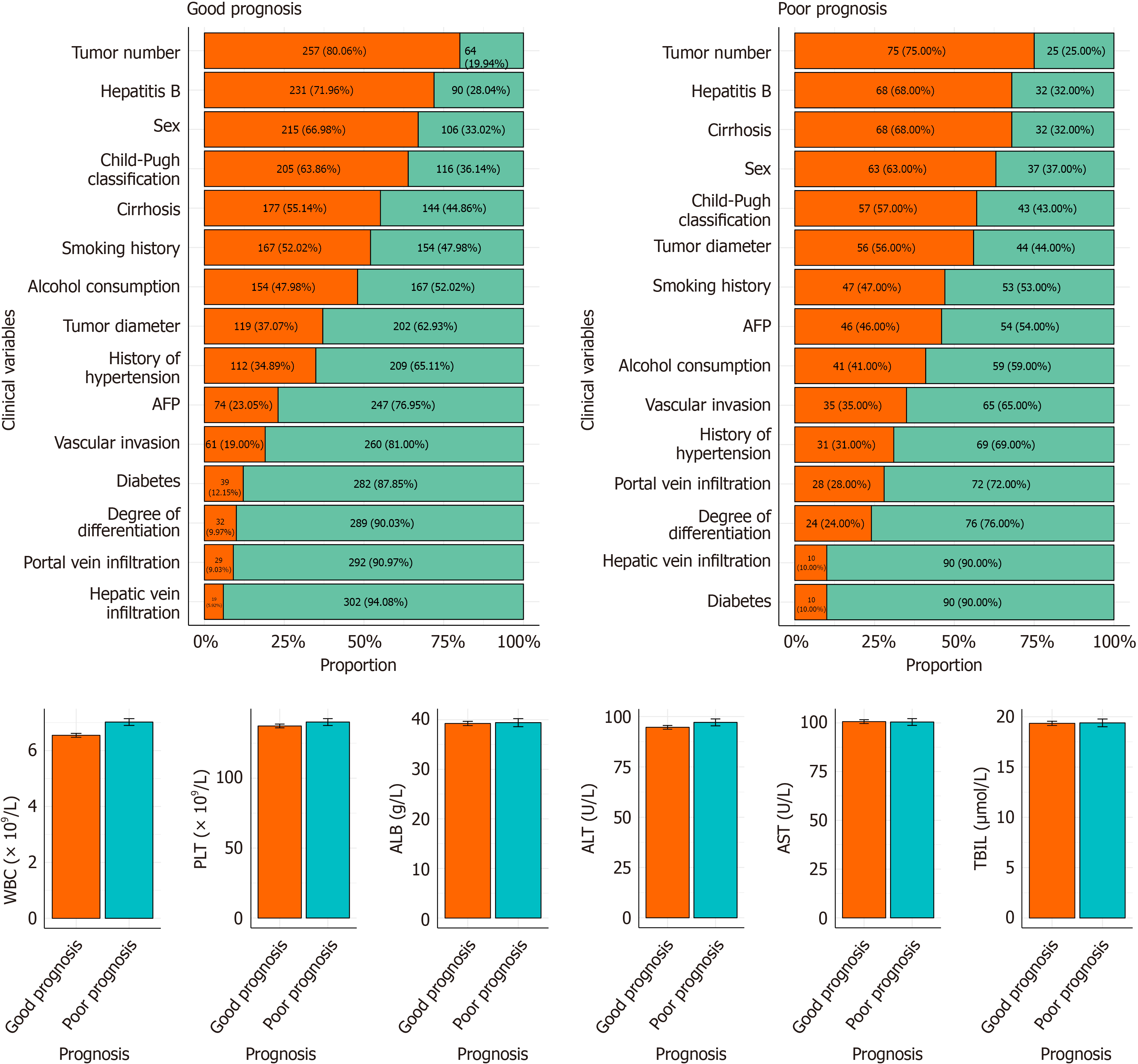

Significant intergroup differences were observed across most clinical variables. The poor-prognosis group included more male, smoking, and alcohol-using patients, whereas the good prognosis group had a higher prevalence of hypertension and diabetes. Poor-prognosis patients more frequently exhibited HBV infection and Child-Pugh grade B liver function. Larger tumor diameters, multiple nodules, and poor differentiation were also significantly associated with poor out

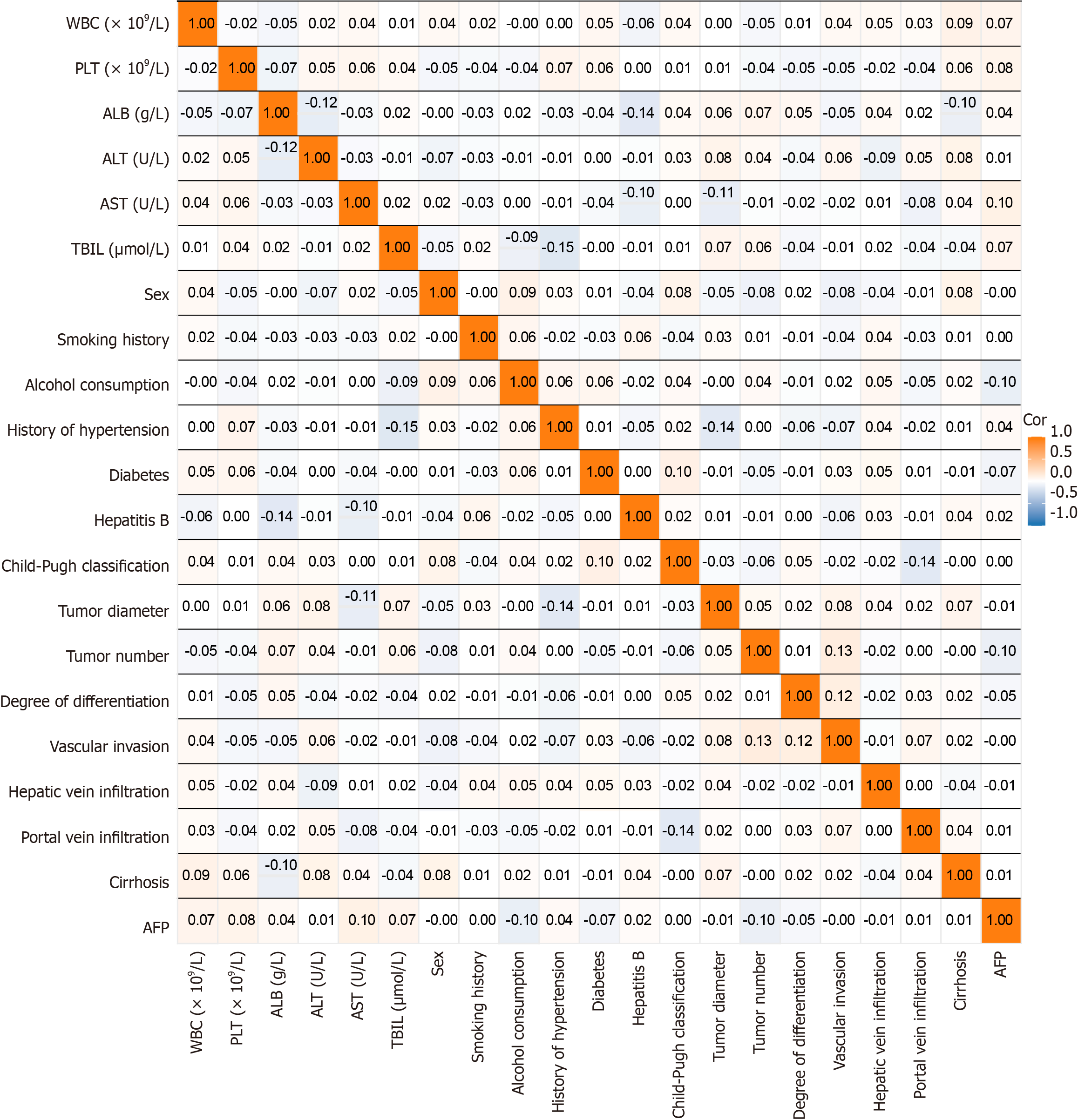

Correlation analyses between clinical and laboratory parameters revealed small correlation coefficients for most variables, indicating no significant linear relationships. For example, WBC and PLT had near-zero correlations with other factors such as hepatic vein infiltration and tumor number. Similarly, ALT and AST showed weak association with liver function-related indicators such as TBIL and Child-Pugh classification. Most coefficients ranged from -0.1 to 0.1, suggesting generally weak correlations. Therefore, no strong linear relationships were detected between clinical characteristics and laboratory indices, indicating that other nonlinear factors may have greater prognostic influence (Figure 2).

When comparing baseline characteristics among the training (n = 277), validation (n = 144), and external validation (n = 138) cohorts, no statistically significant differences were observed across all evaluated variables. Specifically, sex distribution, smoking and alcohol consumption histories, hypertension and diabetes prevalence, HBV infection, Child-Pugh classification, tumor diameter and number, differentiation degree, vascular invasion, hepatic and portal vein infiltration, cirrhosis, and AFP levels showed no statistical differences (all P > 0.05). Similarly, laboratory indices, including WBC count, PLT count, ALB, ALT, AST, and TBIL, were comparable among groups (all P > 0.05). These results confirm that the cohorts had well balanced and statistically comparable baseline characteristics (Table 1).

| Variable | Training group | Validation group | External validation group | Statistical values | P value |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 182 | 96 | 91 | 0.040 | 0.980 |

| Female | 95 | 48 | 47 | ||

| History of smoking | |||||

| Yes | 136 | 78 | 67 | 1.190 | 0.552 |

| No | 141 | 66 | 71 | ||

| History of alcohol consumption | |||||

| Yes | 130 | 65 | 62 | 0.204 | 0.903 |

| No | 147 | 79 | 76 | ||

| History of hypertension | |||||

| Yes | 89 | 54 | 47 | 1.218 | 0.544 |

| No | 188 | 90 | 91 | ||

| History of diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 33 | 16 | 16 | 0.060 | 0.971 |

| No | 244 | 128 | 122 | ||

| Hepatitis B | |||||

| Yes | 193 | 106 | 89 | 2.778 | 0.249 |

| No | 84 | 38 | 49 | ||

| Child-Pugh classification | |||||

| A | 170 | 92 | 85 | 0.273 | 0.872 |

| B | 107 | 52 | 53 | ||

| Tumor diameter | |||||

| ≥ 5 cm | 120 | 55 | 54 | 1.285 | 0.526 |

| < 5 cm | 157 | 89 | 84 | ||

| Tumor number | |||||

| Single | 221 | 111 | 112 | 0.759 | 0.684 |

| Multiple | 56 | 33 | 26 | ||

| Degree of differentiation | |||||

| Poorly differentiated | 36 | 20 | 20 | 0.190 | 0.909 |

| Moderately or well differentiated | 241 | 124 | 118 | ||

| Vascular invasion | |||||

| Yes | 66 | 30 | 35 | 0.853 | 0.653 |

| No | 211 | 114 | 103 | ||

| Hepatic vein infiltration | |||||

| Yes | 18 | 11 | 8 | 0.400 | 0.819 |

| No | 259 | 133 | 130 | ||

| Portal vein infiltration | |||||

| Yes | 37 | 20 | 18 | 0.045 | 0.978 |

| No | 240 | 124 | 120 | ||

| Cirrhosis | |||||

| Yes | 165 | 80 | 79 | 0.664 | 0.717 |

| No | 112 | 64 | 59 | ||

| AFP | |||||

| ≥ 400 μg/L | 75 | 45 | 37 | 0.965 | 0.617 |

| < 400 μg/L | 202 | 99 | 101 | ||

| WBC (× 109/L) | 6.62 ± 1.28 | 6.74 ± 1.24 | 6.55 ± 1.33 | 0.844 | 0.431 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 137.67 ± 24.72 | 138.74 ± 23.50 | 138.56 ± 22.91 | 0.119 | 0.888 |

| ALB (g/L) | 39.03 ± 7.66 | 39.74 ± 7.73 | 38.90 ± 7.83 | 0.520 | 0.595 |

| ALT (U/L) | 95.23 ± 17.37 | 95.34 ± 16.35 | 92.87 ± 17.04 | 1.037 | 0.355 |

| AST (U/L) | 100.87 ± 18.07 | 100.05 ± 17.43 | 100.62 ± 17.58 | 0.100 | 0.905 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 19.42 (16.69, 21.34) | 19.41 (16.59, 22.29) | 19.16 (15.97, 21.18) | 0.873 | 0.646 |

In the training cohort, significant intergroup differences were observed between the good (n = 210) and poor prognosis (n = 67) groups. Tumor diameter, vascular invasion, portal vein infiltration, cirrhosis, and AFP levels differed significantly (P < 0.05). Patients with tumor diameter ≥ 5 cm, vascular invasion, portal vein infiltration, cirrhosis, or AFP ≥ 400 μg/L were more frequent in the poor-prognosis group. WBC count was also statistically higher among poor-prognosis patients (P = 0.011). No significant differences were found in sex, smoking or alcohol history, hypertension, diabetes, HBV infection, Child-Pugh classification, tumor number, differentiation degree, hepatic vein infiltration, PLT, ALB, ALT, AST, or TBIL (P > 0.05; Table 2).

| Variable | Poor prognosis group (n = 67) | Good prognosis group (n = 210) | Statistical values | P value |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 46 | 136 | 0.342 | 0.559 |

| Female | 21 | 74 | ||

| History of smoking | ||||

| Yes | 30 | 106 | 0.660 | 0.416 |

| No | 37 | 104 | ||

| History of alcohol consumption | ||||

| Yes | 32 | 98 | 0.024 | 0.876 |

| No | 35 | 112 | ||

| History of hypertension | ||||

| Yes | 21 | 68 | 0.025 | 0.874 |

| No | 46 | 142 | ||

| History of diabetes | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 23 | 0.764 | 0.382 |

| No | 57 | 187 | ||

| Hepatitis B | ||||

| Yes | 46 | 147 | 0.043 | 0.835 |

| No | 21 | 63 | ||

| Child-Pugh classification | ||||

| A | 41 | 129 | 0.001 | 0.973 |

| B | 26 | 81 | ||

| Tumor diameter | ||||

| ≥ 5 cm | 37 | 83 | 5.099 | 0.024 |

| < 5 cm | 30 | 127 | ||

| Tumor number | ||||

| Single | 48 | 173 | 3.632 | 0.057 |

| Multiple | 19 | 37 | ||

| Degree of differentiation | ||||

| Poorly differentiated | 13 | 23 | 3.208 | 0.073 |

| Moderately or well differentiated | 54 | 187 | ||

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| Yes | 23 | 43 | 5.370 | 0.020 |

| No | 44 | 167 | ||

| Hepatic vein infiltration | ||||

| Yes | 6 | 12 | 0.878 | 0.349 |

| No | 61 | 198 | ||

| Portal vein infiltration | ||||

| Yes | 15 | 22 | 6.228 | 0.013 |

| No | 52 | 188 | ||

| Cirrhosis | ||||

| Yes | 47 | 118 | 4.109 | 0.043 |

| No | 20 | 92 | ||

| AFP | ||||

| ≥ 400 μg/L | 33 | 42 | 22.015 | < 0.001 |

| < 400 μg/L | 34 | 168 | ||

| WBC (× 109/L) | 6.96 ± 1.25 | 6.51 ± 1.27 | 2.583 | 0.011 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 141.88 ± 25.84 | 136.32 ± 24.27 | 1.555 | 0.123 |

| ALB (g/L) | 38.28 ± 8.21 | 39.27 ± 7.48 | -0.886 | 0.378 |

| ALT (U/L) | 96.51 ± 17.76 | 94.83 ± 17.27 | 0.679 | 0.499 |

| AST (U/L) | 100.42 ± 18.82 | 101.01 ± 17.87 | -0.224 | 0.823 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 19.39 ± 3.73 | 19.22 ± 3.61 | 0.33 | 0.742 |

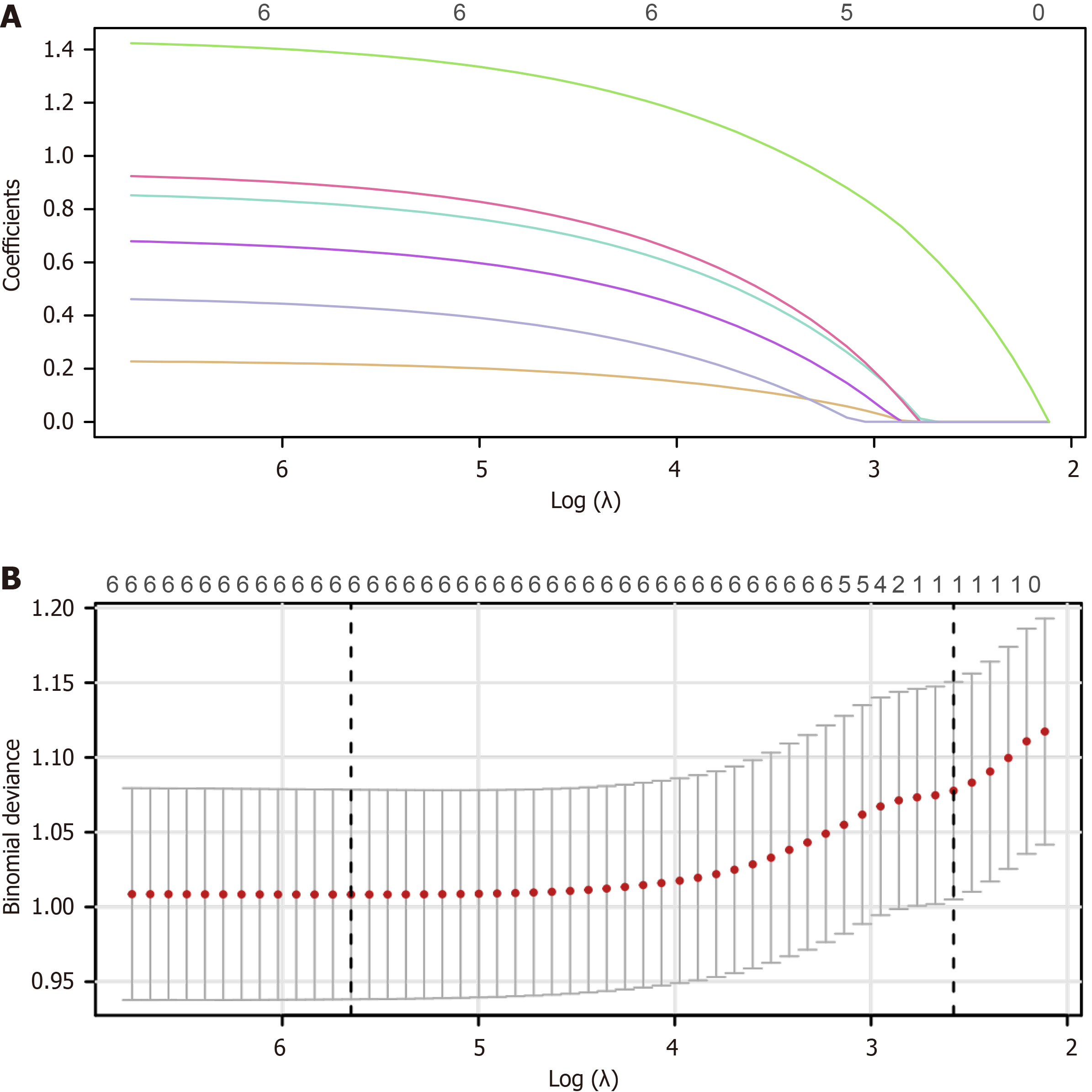

Using LASSO regression, six prognostic variables were identified: WBC count, tumor diameter, vascular invasion, portal vein infiltration, cirrhosis, and AFP level (Figure 3). The optimal penalty parameter was λ = 0.0035191, determined through cross-validation. Regression coefficients were 0.216 for WBC count, 0.644 for tumor diameter, 0.813 for vascular invasion, 0.883 for portal vein infiltration, 0.431 for cirrhosis, and 1.385 for AFP level. The model formula was Logit(P) =

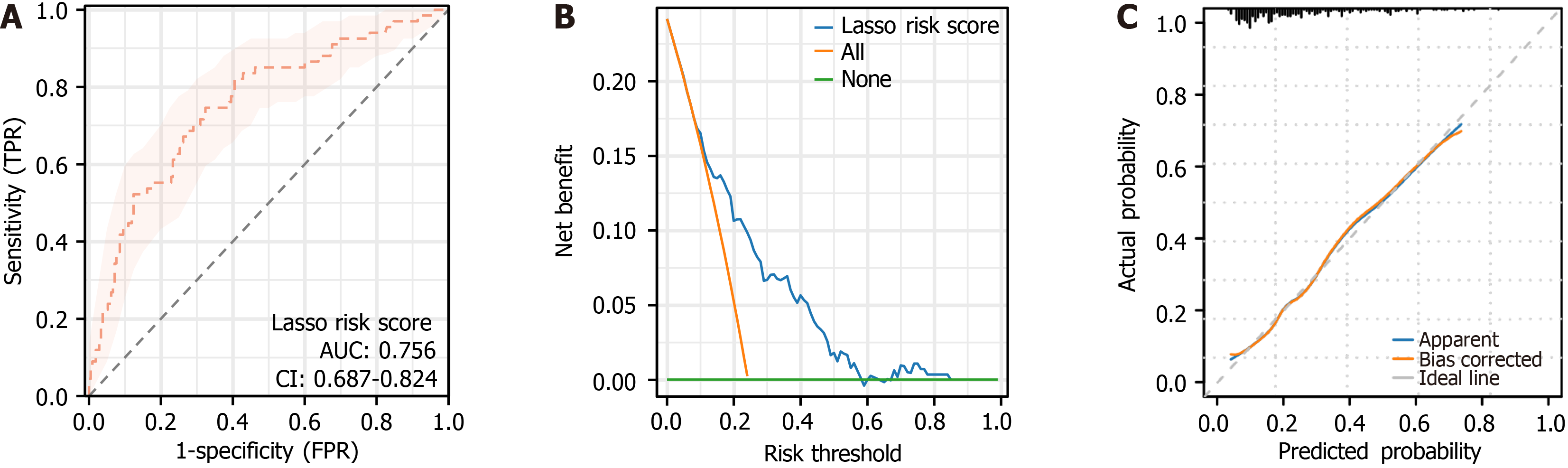

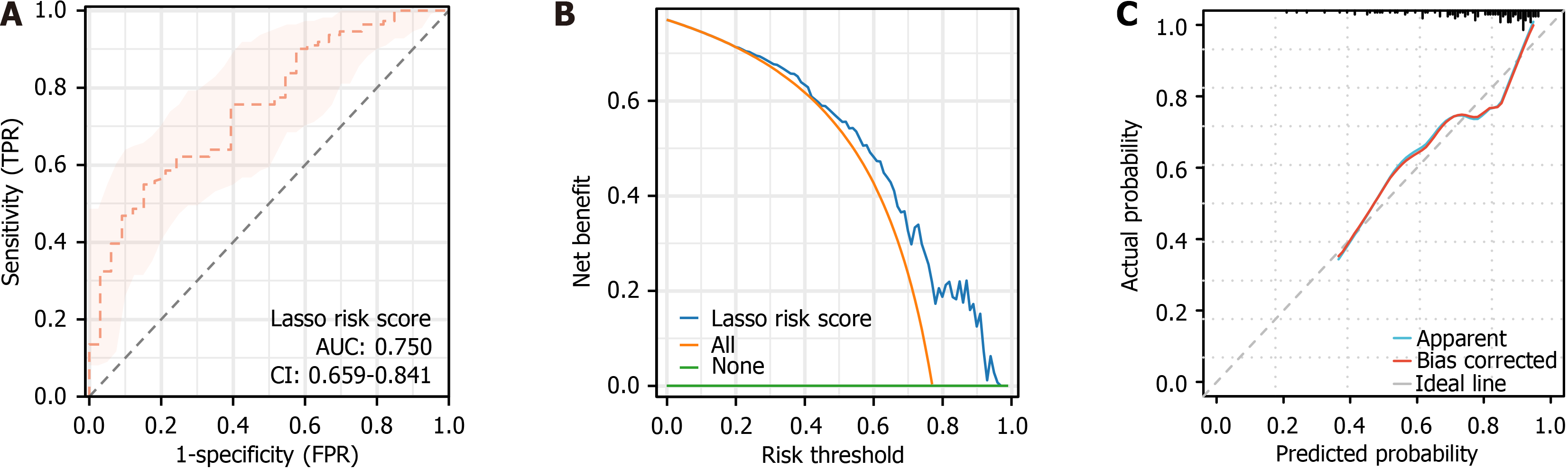

In the training cohort, ROC curve (Figure 4A) showed an AUC of 0.756 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.687-0.824; P = 1.89 × 10-13], indicating good discriminatory power in distinguishing good from poor-prognosis patients. DCA curve (Figure 4B) demonstrated a high clinical net benefit across risk thresholds of 0%-84%, with a maximum benefit of 24.18%. The goodness-of-fit test of the calibration curve (Figure 4C) showed that the model was well calibrated (χ2 = 5.5714, P = 0.6951).

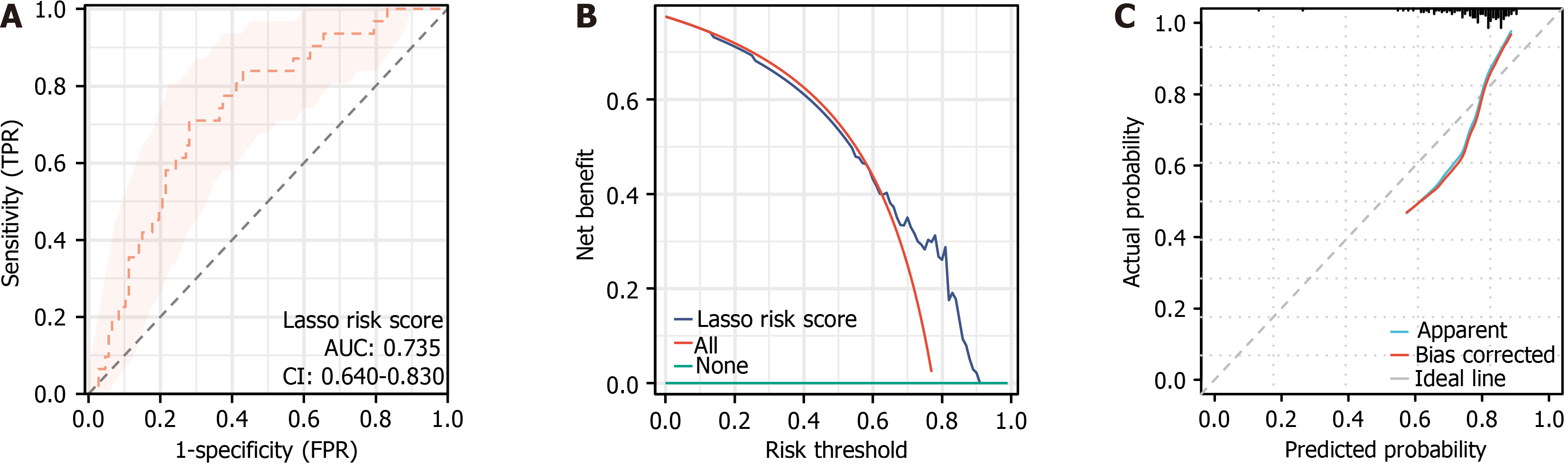

In the validation cohort, the LASSO model was evaluated and validated using ROC curves, DCA, and calibration plots. The ROC curve (Figure 5A), yielded an AUC of 0.750 (95%CI: 0.659-0.841; P = 4.76E-8), confirming strong discrimination between favorable and unfavorable clinical outcomes. The DCA curve (Figure 5B) showed robust net benefit across risk thresholds of 0%-96%, while the goodness-of-fit test result of the calibration plot (Figure 5C) indicated strong model calibration (χ2 = 8.2821, P = 0.4064).

In the external validation cohort, the LASSO model achieved an AUC of 0.735 (95%CI: 0.640-0.830, P = 9.58E-07) in ROC analysis (Figure 6A), demonstrating reliable discrimination between patients at high and low risk of poor outcomes. The DCA curve (Figure 6B) revealed a positive clinical net benefit within the 0%-90% threshold probability range, peaking at 77.53%. The calibration plot (Figure 6C) showed strong agreement between predicted and observed outcomes, supported by goodness-of-fit testing (χ2 = 7.1336, P = 0.5223).

The ROC curve parameters of the LASSO-derived risk score were consistent across the training and validation cohorts, confirming stable discriminatory performance. The AUC values were 0.756 (95%CI: 0.687-0.824) for the training cohort and 0.750 (95%CI: 0.659-0.841) for the validation cohort. In the training cohort, sensitivity, specificity, and Youden index were 74.63%, 67.62%, and 42.25%, respectively; in the validation cohort, these values were 84.85%, 54.95%, and 39.80%. The optimal cut-off values were -1.256 (training) and -1.604 (validation). Model accuracy, precision, and F1 score in the training cohort were 69.31%, 74.63%, and 54.05%, respectively, compared with 61.81%, 84.85%, and 50.45% in the validation cohort (Table 3). These findings underscore the model’s consistent and robust discrimination across datasets.

| Marker | AUC | 95%CI | Specificity, % | Sensitivity, % | Youden index, % | Cut off | Accuracy, % | Precision | F1 score, % |

| LASSO risk score (training group) | 0.756 | 0.687-0.824 | 67.62 | 74.63 | 42.25 | -1.256 | 69.31 | 74.63 | 54.05 |

| LASSO risk score (validation group) | 0.75 | 0.659-0.841 | 54.95 | 84.85 | 39.80 | -1.604 | 61.81 | 84.85 | 50.45 |

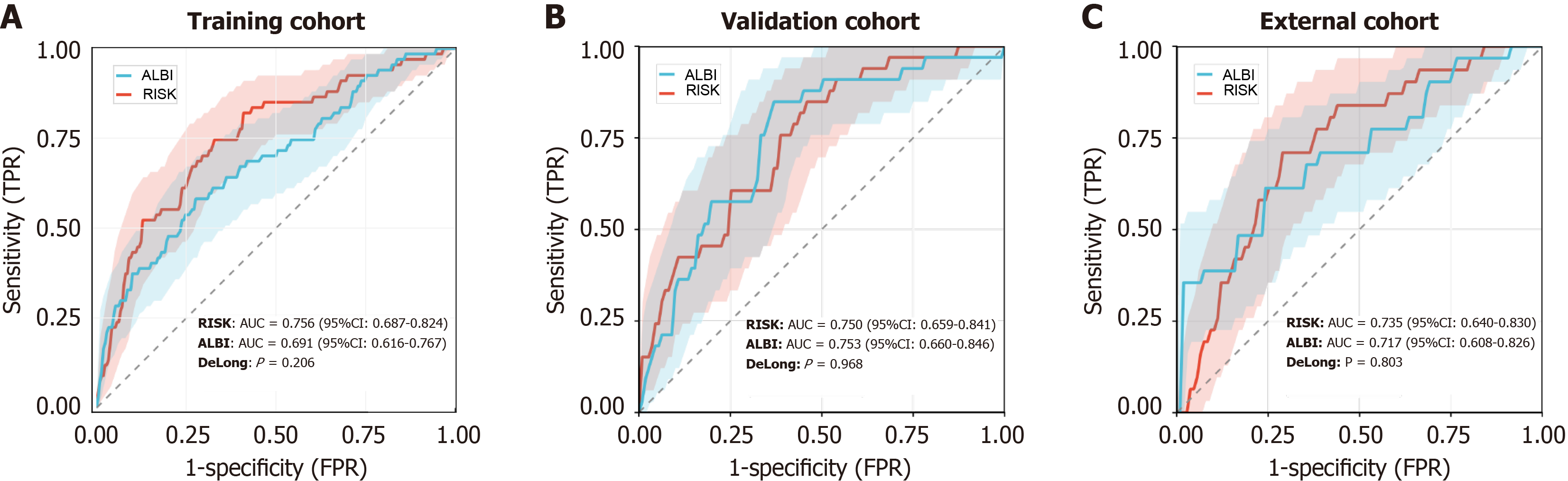

Compared with the ALBI score, the LASSO-based risk score consistently demonstrated higher discriminatory ability across all cohorts. In the training cohort, risk score achieved a higher AUC than ALBI (0.756 vs 0.691; DeLong P = 0.206, Figure 7A). The improvement persisted in the validation (0.750 vs 0.753; DeLong P = 0.968, Figure 7B) and external (0.735 vs 0.717; DeLong P = 0.803, Figure 7C) cohorts. Although statistical significance was reached only in the training cohort, the direction and magnitude of improvement were consistent, supporting the LASSO model’s incremental predictive value beyond ALBI.

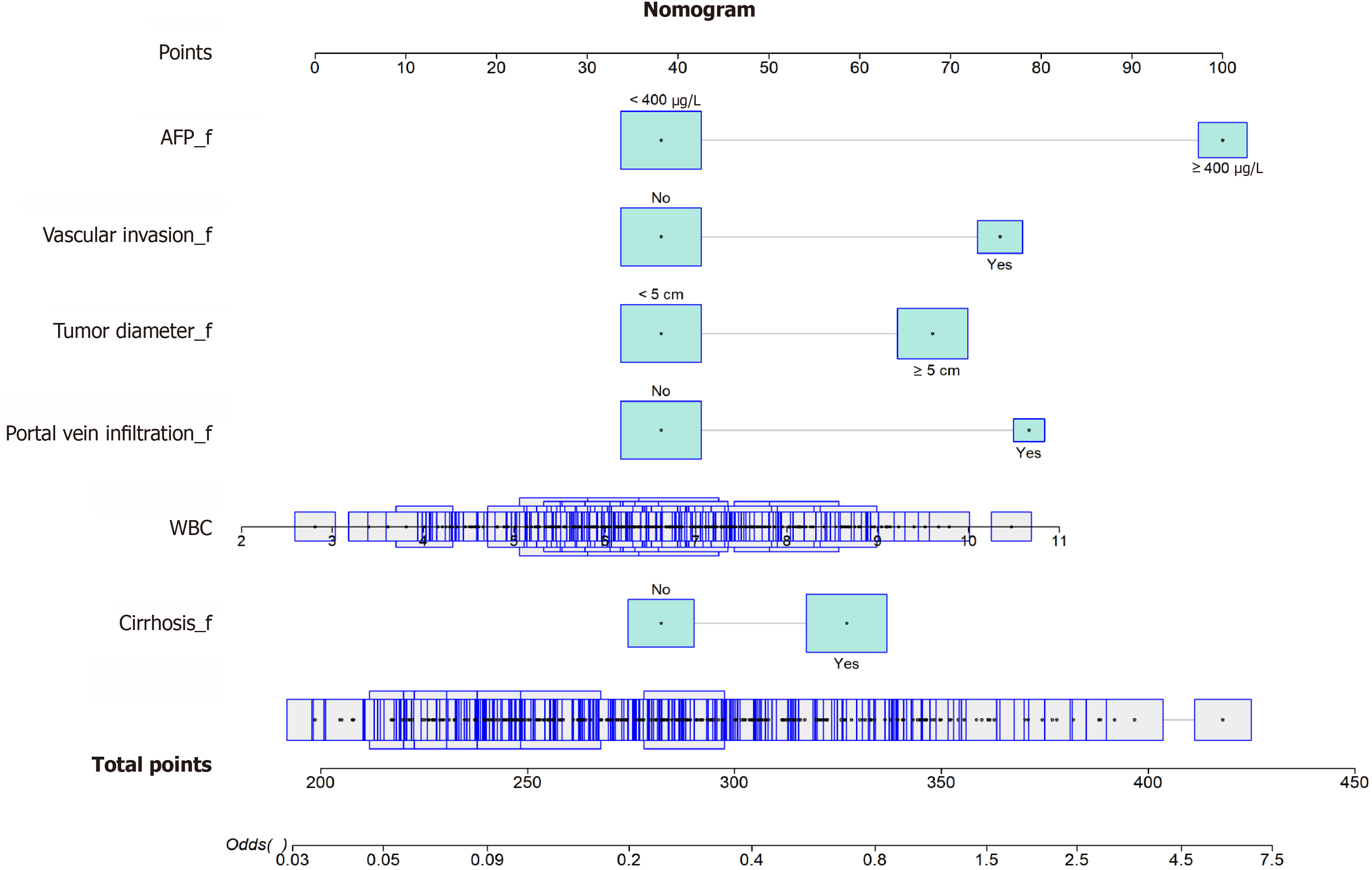

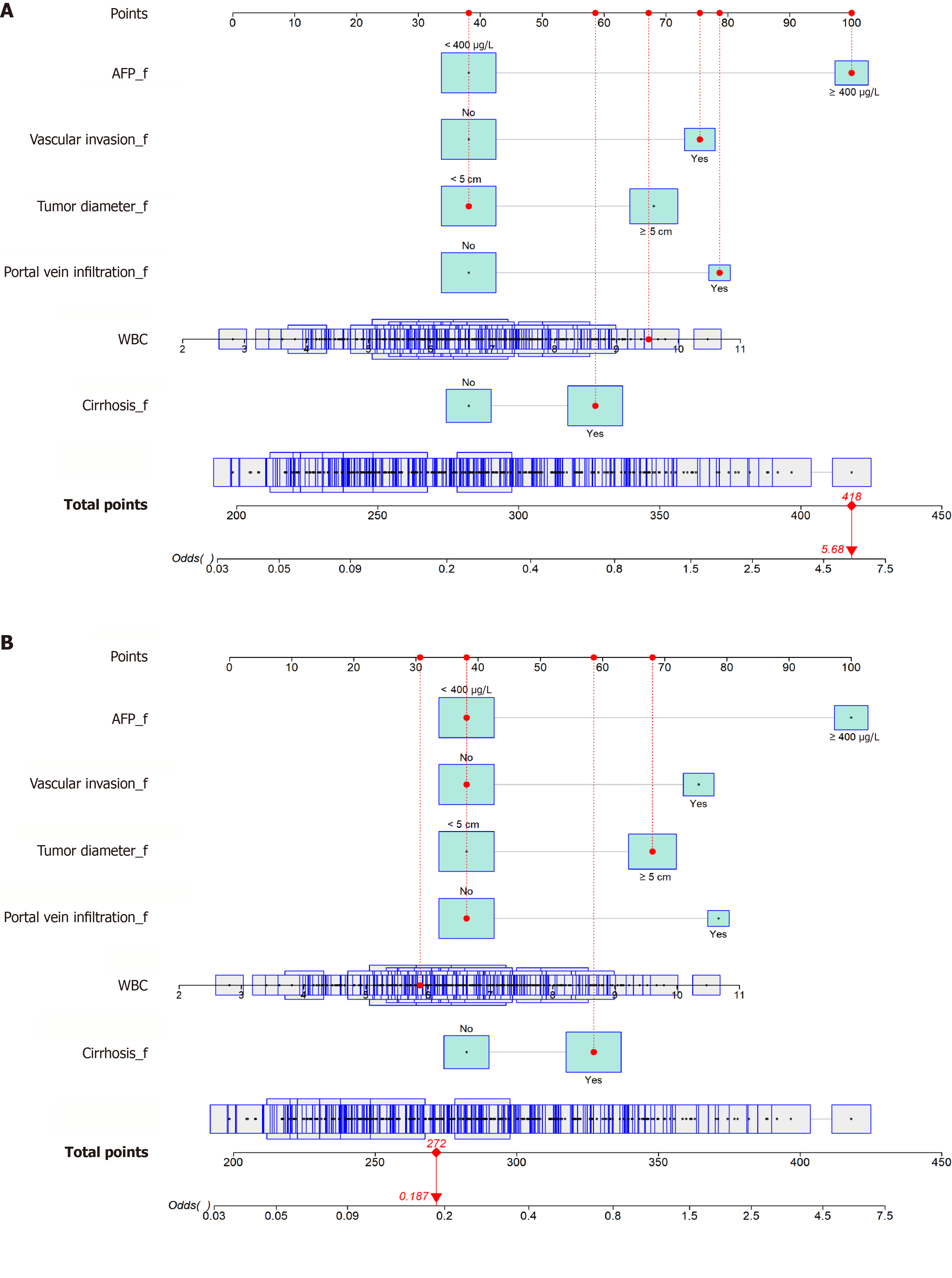

A prognostic nomogram model (Figure 8) was developed using the six LASSO-identified variables, WBC count, tumor diameter, vascular invasion, portal vein infiltration, cirrhosis, and AFP, to estimate individualized prognosis. Each variable contributed a weighted score, and the total score was used to calculate the probability of poor prognosis. For instance, of the two patients randomly selected, patient 1 had a total score of 418, corresponding to a 100% poor prognosis probability, whereas patient 2 scored 268 points, corresponding to a 32.5% poor prognosis (Figure 9; Table 4). This model effectively distinguished patients with different prognoses, demonstrating high predictive accuracy.

| Variable | Patient 1 | Patient 2 |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 9.52 | 5.5 |

| Tumor diameter | < 5 cm | ≥ 5 cm |

| Vascular invasion | Yes | No |

| Portal vein infiltration | Yes | No |

| Cirrhosis | Yes | Yes |

| AFP | ≥ 400 μg/L | < 400 μg/L |

| Total score | 418 | 268 |

| Probability of poor prognosis | 100% | 32.5% |

Through retrospective analysis, six risk factors, WBC count, tumor diameter, vascular invasion, portal vein infiltration, liver cirrhosis, and AFP level, were identified as strongly associated with poor prognosis after minimally invasive resection for PLC. The logistic regression model constructed based on these variables achieved AUCs of 0.756 and 0.750 in the training and validation cohorts, respectively, demonstrating strong discriminatory ability in predicting one-year postoperative outcomes. The DCA and calibration curves further confirmed the model’s clinical applicability and good calibration, supporting its potential for use in clinical decision-making.

The six prognostic factors identified in this study align closely with established findings. For instance, AFP, a widely recognized HCC biomarker, correlates with tumor aggressiveness and recurrence. Li et al[17] developed a prognostic model for elderly patients with PLC using the SEER database and identified AFP as a key prognostic indicator. Similarly, tumor diameter and vascular invasion have been repeatedly validated as major prognostic determinants in LC. Nevola et al[18] observed higher early recurrence and metastasis rates in patients with larger tumors, whereas vascular invasion remains a hallmark of tumor invasion.

This study specifically focused on patients undergoing minimally invasive resection, a population rarely examined in prior research, offering new insights into prognostic evaluation following this approach. While previous models have been developed for non-cirrhotic HCC[19] or LC with microvascular invasion[20], this study employed LASSO regression to manage multivariate complexity and enhance model generalizability. Compared with traditional logistic regression model, LASSO mitigates overfitting and improves predictive accuracy.

Elevated WBC count, an inflammation marker, may reflect an exacerbated tumor-related inflammatory state, which has been linked to poor outcomes across malignancies. Zhan et al[21] emphasized the prognostic role of inflammatory markers in LC. Larger tumor diameter typically correlates with higher recurrence and metastasis risks due to increased tumor burden and invasiveness. Brustia et al[22] identified tumor diameter as a key predictor of postoperative complications and long-term prognosis. Vascular invasion, indicative of high metastatic potential, consistently predicts unfavorable outcomes. Portal vein infiltration further suggests advanced tumor invasiveness, contributing to greater recurrence risk and poor survival, as confirmed by Yang et al[23]. Liver cirrhosis, reflecting impaired hepatic function, compromises postoperative recovery and long-term outcomes and is therefore an essential background factor in LC progression. Prior studies have associated liver cirrhosis with delayed recovery and increased recurrence. Elevated AFP serves not only as a diagnostic biomarker but also an indicator of tumor invasiveness and recurrence potential, mirroring the biological behavior of malignant hepatocytes[24,25]. Liu et al[26] also confirmed the importance of AFP in LC. Even among AFP-negative cases, factors such as tumor diameter and vascular invasion remain critical predictors. In the logistic regression model, AFP exhibited the strongest association with poor prognosis, followed by portal vein infiltration and vascular invasion, highlighting their dominant predictive roles. WBC count and cirrhosis had smaller but significant effects, underscoring their value in comprehensive prognostic assessment.

Thus, the LASSO regression-based early-warning model can effectively identify high-risk patients soon after surgery and assist clinicians in developing individualized follow-up and management plans. For instance, high-risk patients may require more frequent imaging and proactive adjuvant therapy to lower recurrence or metastasis risk[27]. Early identification and intervention can significantly reduce postoperative recurrence, prolong survival, and enhance well-being[28,29], optimizing treatment outcomes while easing healthcare system burdens. The SEER-based prediction model has also proven useful for clinical decision-making, improving treatment precision and individualization[21]. Similar models by He et al[30] and Zhou et al[31] achieved good predictive ability; however, our model demonstrated higher AUC and C-index values, particularly in the validation cohort, reflecting superior generalization.

Compared with existing models, our individualized early-warning model offers better accuracy and clinical applicability. Li et al[17] developed a SEER-based prognostic model for elderly patients with PLC with C-indices of 0.747 and 0.773 in training and validation cohorts, respectively, while our model achieved comparable AUC values (0.756 and 0.750). Zhou et al[31] established a LASSO Cox regression model for AFP-negative patients with LC (C-index = 0.752 in the validation cohort), also comparable to our model results. The cancer-specific survival model by Yang et al[23] for LC patients with microvascular invasion yielded C-indices of 0.785 and 0.776, indicating slightly higher predictive accuracy. Nevertheless, our external validation demonstrated an AUC of 0.735 (95%CI: 0.640-0.830) for the LASSO model, confirming consistent and robust discrimination in an independent PLC cohort. The model’s net clinical benefit was 0%-90% threshold probabilities, peaking at 77.53%. Its calibration curve also indicated close agreement between predicted and observed outcomes (χ2 = 7.1336, P = 0.5223), confirming good calibration. Collectively, these results shows that our model reliably predicts postoperative prognosis and remains competitive with comparable models. Its strong applicability across different populations and treatment modalities further supports its clinical utility.

This study offers several strengths: A large sample size (277 patients in the training and 144 patients in the validation cohorts) that enhances statistical power and result reliability; variable screening through LASSO regression, which reduces model complexity and boosts generalizability; and model validation using ROC, DCA, and calibration analyses to ensure predictive accuracy and clinical value. However, certain limitations exist. First, all data were sourced from a single hospital, which may restrict the model’s generalizability to other regions or healthcare settings. Second, as a retrospective study, selection bias may affect result authenticity and reliability. Third, the model lacks validation on other independent datasets, necessitating further testing in diverse populations. Finally, genetic background and lifestyle factors were not included, possibly omitting relevant prognostic factors. As Li et al[17] noted, multicenter and prospective studies are essential to enhance the model’s universality and precision.

Future research should focus on external validation across hospitals and regions to assess model performance in diverse populations and enhance its universality and reliability. Prospective cohort studies are also warranted to minimize biases inherent in retrospective designs and to further verify predictive accuracy. Additionally, refining the model by incorporating more clinical and molecular biology indicators, such as gene expression profiles and tumor microenvironmental features, could improve precision. Translating the model into a clinical decision support system and evaluating its utility and impact in real-world clinical settings would facilitate broader clinical adoption. Furthermore, exploring the biological mechanisms underlying the identified LC prognostic factors could clarify their roles in tumor progression and provide a theoretical basis for targeted therapy. Yang et al[23] and Zhan et al[21] similarly emphasized integrating clinical factors with multiple biomarkers to enhance model comprehensiveness and prognostic accuracy.

This study identified six risk factors significantly associated with poor prognosis in PLC after minimally invasive resection using LASSO regression and developed an individualized early-warning model with strong predictive performance and calibration. The model demonstrated high discriminatory ability and clinical utility in both training and validation cohorts and may aid in early identification of high-risk patients, optimizing postoperative management and follow-up strategies to extend survival and improve quality of life. Future multicenter and prospective studies are needed to further validate and optimize this model, ensuring its broad applicability and reliability across diverse populations.

| 1. | Nan Y, Xu X, Dong S, Yang M, Li L, Zhao S, Duan Z, Jia J, Wei L, Zhuang H; Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association. Consensus on the tertiary prevention of primary liver cancer. Hepatol Int. 2023;17:1057-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vogel A, Meyer T, Sapisochin G, Salem R, Saborowski A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2022;400:1345-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1284] [Cited by in RCA: 1573] [Article Influence: 393.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (42)] |

| 3. | Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, Lesi O, Cabasag CJ, Vignat J, Laversanne M, McGlynn KA, Soerjomataram I. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1598-1606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 1401] [Article Influence: 350.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J, Finn RS. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4432] [Cited by in RCA: 4438] [Article Influence: 887.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 5. | Singal AG, Kanwal F, Llovet JM. Global trends in hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology: implications for screening, prevention and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:864-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 577] [Cited by in RCA: 528] [Article Influence: 176.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Tang A, Hallouch O, Chernyak V, Kamaya A, Sirlin CB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: target population for surveillance and diagnosis. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43:13-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264-1273.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2183] [Cited by in RCA: 2562] [Article Influence: 183.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | Huang DQ, Hoang JK, Kamal R, Tsai PC, Toyoda H, Yeh ML, Yasuda S, Leong J, Maeda M, Huang CF, Won Jun D, Ishigami M, Tanaka Y, Uojima H, Ogawa E, Abe H, Hsu YC, Tseng CH, Alsudaney M, Yang JD, Yoshimaru Y, Suzuki T, Liu JK, Landis C, Dai CY, Huang JF, Chuang WL, Schwartz M, Dan YY, Esquivel C, Bonham A, Yu ML, Nguyen MH. Antiviral Therapy Utilization and 10-Year Outcomes in Resected Hepatitis B Virus- and Hepatitis C Virus-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:790-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Birgin E, Hetjens S, Tam M, Correa-Gallego C, Rahbari NN. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy versus Surgical Resection for Stage I/II Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:2330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Eugen K. Current treatment options for hepatocellular carcinoma. Klin Onkol. 2020;33:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fuster-Anglada C, Mauro E, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Caballol B, Sanduzzi-Zamparelli M, Bruix J, Fuster J, Reig M, Díaz A, Forner A. Histological predictors of aggressive recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection. J Hepatol. 2024;81:995-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gonvers S, Martins-Filho SN, Hirayama A, Calderaro J, Phillips R, Uldry E, Demartines N, Melloul E, Park YN, Paradis V, Thung SN, Alves V, Sempoux C, Labgaa I. Macroscopic Characterization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Underexploited Source of Prognostic Factors. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2024;11:707-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang Q, Qiao W, Zhang H, Liu B, Li J, Zang C, Mei T, Zheng J, Zhang Y. Nomogram established on account of Lasso-Cox regression for predicting recurrence in patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1019638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bureau of Medical Administration, National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. [Standardization for diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (2022 edition)]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2022;30:367-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cichos KH, Jordan E, Niknam K, Chen AF, Hansen EN, McGwin G Jr, Ghanem ES. Child-Pugh Class B or C Liver Disease Increases the Risk of Early Mortality in Patients With Hepatitis C Undergoing Elective Total Joint Arthroplasty Regardless of Treatment Status. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2023;481:2016-2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhang R, Hu L, Cheng Y, Chang L, Dong L, Han L, Yu W, Zhang R, Liu P, Wei X, Yu J. Targeted sequencing of DNA/RNA combined with radiomics predicts lymph node metastasis of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Imaging. 2024;24:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Li F, Zheng T, Gu X. Prognostic risk factor analysis and nomogram construction for primary liver cancer in elderly patients based on SEER database. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e051946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nevola R, Ruocco R, Criscuolo L, Villani A, Alfano M, Beccia D, Imbriani S, Claar E, Cozzolino D, Sasso FC, Marrone A, Adinolfi LE, Rinaldi L. Predictors of early and late hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:1243-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 54.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 19. | Huang G, Lin Q, Yin P, Mao K, Zhang J. Development and validation of web-based prognostic nomograms for massive hepatocellular carcinoma (≥10 cm): A retrospective study based on the SEER database. Cancer Med. 2023;12:13167-13181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yang D, Zhu M, Xiong X, Su Y, Zhao F, Hu Y, Zhang G, Pei J, Ding Y. Clinical features and prognostic factors in patients with microvascular infiltration of hepatocellular carcinoma: Development and validation of a nomogram and risk stratification based on the SEER database. Front Oncol. 2022;12:987603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhan G, Cao P, Peng H. Construction of web-based prediction nomogram models for cancer-specific survival in patients at stage IV of hepatocellular carcinoma depending on SEER database. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2023;48:1546-1560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Brustia R, Fleres F, Tamby E, Rhaiem R, Piardi T, Kianmanesh R, Sommacale D. Postoperative collections after liver surgery: Risk factors and impact on long-term outcomes. J Visc Surg. 2020;157:199-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yang D, Su Y, Zhao F, Chen C, Zhao K, Xiong X, Ding Y. A Practical Nomogram and Risk Stratification System Predicting the Cancer-Specific Survival for Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:914192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jin Y, Xu A. Clinical value of serum AFP and PIVKA-II for diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal. 2024;38:e25016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lu LH, Wei-Wei, Kan A, Jie-Mei, Ling YH, Li SH, Guo RP. Novel Value of Preoperative Gamma-Glutamyltransferase Levels in the Prognosis of AFP-Negative Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Dis Markers. 2020;2020:4269460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liu C, Li Z, Zhang Z, Li J, Xu C, Jia Y, Zhang C, Yang W, Wang W, Wang X, Liang K, Peng L, Wang J. Prediction of survival and analysis of prognostic factors for patients with AFP negative hepatocellular carcinoma: a population-based study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sun L, Wu Z, Dong C, Yu S, Huang H, Chen Z, Wu Z, Yin X. Signature construction and molecular subtype identification based on immune-related genes for better prediction of prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Med Genomics. 2023;16:130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ye K, Fan Q, Yuan M, Wang D, Xiao L, Long G, Chen R, Fang T, Li Z, Zhou L. Prognostic Value of Postoperative Circulating Tumor DNA in Patients With Early- and Intermediate-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:834992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kong J, Wang T, Shen S, Zhang Z, Yang X, Wang W. A genomic-clinical nomogram predicting recurrence-free survival for patients diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | He T, Chen T, Liu X, Zhang B, Yue S, Cao J, Zhang G. A Web-Based Prediction Model for Cancer-Specific Survival of Elderly Patients With Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Study Based on SEER Database. Front Public Health. 2021;9:789026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zhou D, Liu X, Wang X, Yan F, Wang P, Yan H, Jiang Y, Yang Z. A prognostic nomogram based on LASSO Cox regression in patients with alpha-fetoprotein-negative hepatocellular carcinoma following non-surgical therapy. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/