Published online Feb 14, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i6.113010

Revised: October 23, 2025

Accepted: December 11, 2025

Published online: February 14, 2026

Processing time: 173 Days and 23.7 Hours

A high-fat diet (HFD) can cause systemic low-grade inflammation, metabolic and inflammatory diseases, and alter the composition of intestinal microbiota. Although probiotics mitigate intestinal inflammation, it is still unclear whether they can directly inhibit the production of deoxycholic acid (DCA) to prevent or alleviate intestinal inflammation.

To investigate changes in intestinal flora, fecal DCA levels, and cytokine profiles.

Vancomycin was administered to significantly reduce the population of intestinal gram-positive bacteria, which helped in reducing the fecal DCA levels. Recruit

HFD or DCA promotes the infiltration of colon macrophages, causing their polari

Bifidobacterium can inhibit HFD-induced intestinal inflammation or that resulting from DCA-induced M1 pola

Core Tip: A high-fat diet increases fecal deoxycholic acid (DCA), inducing M1 macrophage polarization and intestinal inflammation. Bifidobacterium mitigates this by reducing the production of DCA, inhibiting M1 polarization, and partially restoring gut microbiota balance. Hence, they can be employed for treating high-fat diet-associated colitis. This study aims to investigate changes in intestinal flora, fecal DCA levels, and cytokine profiles.

- Citation: Yang PC, Xiao CY, Wang J, Yan CH, Li QY, Li SY, Li J, Zhang LJ, Dai CB. Effects and mechanism of Bifidobacterium on intestinal inflammation resulting from deoxycholic acid-induced M1 polarization of macrophages. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(6): 113010

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i6/113010.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i6.113010

The human digestive tract hosts approximately 1000 different species of bacteria. The gut microbiota maintains a dynamic balance within the intestinal environment[1]. Any disruption of this balance due to various factors can lead to a range of diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and even extraintestinal disorders like cardiovascular disease and autism[2-5]. A prolonged high-fat diet (HFD) can alter the structure and ecology of the intestinal flora, damaging intestinal epithelial cells and compromising the integrity of the intestinal barrier. This phenomenon results in increased intestinal permeability and a higher proportion of gram-negative bacteria in the digestive tract, which consequently leads to an elevation in intestinal lipopolysaccharides (LPS)[6,7]. The LPS can activate Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) via the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) transcription factor signaling pathway, triggering an intestinal inflammatory response[8].

Myeloid cells, especially macrophages, are indispensable for clearing pathogens and regulating intestinal inflammatory responses. Depending on their activation status, macrophages are categorized into pro-inflammatory M1 phenotypes (classical activation) and anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes (alternative activation). M1 macrophages secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-1β, along with reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen intermediates, which trigger inflammatory responses and aid in pathogen elimination, thus demonstrating immune surveillance. In contrast, M2 macrophages generally produce anti-inflammatory factors, including IL-4, IL-10, and transforming growth factor-β, which reduce excessive inflammation and foster tissue healing and remodeling. An imbalance between M1 and M2 macrophages can lead to the development of IBD. Importantly, research suggests that a short-term HFD increases the population of pro-inflammatory macrophages in the colonic lamina propria and also enhances the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, highlighting the critical role of M1 macrophages in HFD-related colonic inflammation[9].

Microorganisms and their metabolites in the colon are crucial for coordinating immune responses and maintaining intestinal homeostasis[10]. HFD induces changes in gut microbiota that may result in the secretion of secondary bile acids, particularly deoxycholic acid (DCA). DCA, a secondary bile acid produced by gram-positive 7α-dehydroxylating bacteria, is implicated in the development of IBD and gastrointestinal cancer in a dose-dependent manner[11-13]. HFD can increase fecal DCA concentrations by nearly tenfold, while DCA promotes the polarization of macrophages toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype (M1), thereby facilitating the onset of colitis. The activation of the NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3 inflammasome by DCA is a critical mechanism that enhances the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, in macrophages, leading to the exacerbation of colonic inflammation[13,14]. Additionally, chronic supplementation of animals with a DCA-enriched diet can induce significant colonic inflammation, resembling human IBD[15].

Probiotics have been shown to reduce the differentiation of monocytes into M1 macrophages and inhibit the activation of the NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinases pathways, thereby decreasing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α[16-18]. Furthermore, probiotics enhance the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) through intestinal fermentation, which play a crucial anti-inflammatory role by promoting the differentiation of macrophages into the M2 phenotype and increasing the production of IL-10, a key factor in tissue repair and resolution of inflammation[19-21]. Certain Bifidobacterium strains express bile salt hydrolases, enzymes that deconjugate primary bile acids (e.g., cholic acid), altering their physicochemical properties and metabolic fates. As a result, there is a decrease in the total concentration of the substrate available for bacterial conversion into secondary bile acids such as DCA, a known promoter of gut inflammation and carcinogenesis. Bifidobacterium demonstrates high bile salt hydrolase activity and resilience in the gut environment; the enzymatic deconjugation of bile acids not only enhances the survival and colonization of Bifidobacterium in the gut but also influences host metabolism, immune responses, and disease outcomes[22-24]. However, very few reports are available on whether Bifidobacteria directly prevent or alleviate intestinal inflammation by reducing the production of DCA. This study aims to clarify the relationship between the HFD-induced increase in the concentration of microbial metabolite DCA, macrophage polarization, and colon inflammation.

C57BL/6 and specific pathogen free 6-week-old male mice (n = 42) were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of China Three Gorges University, and housed at the animal center of the same institution. The ambient temperature for animal housing was maintained at 22 ± 2 °C, with appropriate humidity and lighting, along with sufficient feed and drinking water and dry, clean bedding. The experiment adhered to the guidelines for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals established by the China Three Gorges University and received approval from its Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

After a week of adaptive feeding, the male C57BL/6 specific pathogen free mice were randomly assigned to seven groups: General (N), HFD (H), HFD supplemented with Bifidobacterium (H-S), HFD with vancomycin (H-V), HFD with vancomycin and Bifidobacterium (H-V-S), HFD with vancomycin and DCA (H-V-D), and HFD with vancomycin, DCA, and Bifidobacterium (H-V-D-S). Each group consisted of six mice, and their weights were recorded. All groups, except for group N that received a standard diet (1.5 g of feed per 10 g of body weight per day), were fed ad libitum a diet that provided 60% of energy from fat. (1) Group N: Participants were subjected to a common diet for 12 weeks. Daily gastric gavage using a saline solution was conducted in the last 4 weeks; (2) Group H: Participants followed HFD for 12 weeks. High-fat modeling was conducted in the first 8 weeks, followed by daily gastric gavage of saline solution in the last 4 weeks; (3) Group H-S: Participants adhered to the HFD for 12 weeks, with high-fat modeling during the first 8 weeks, followed by daily gastric gavage of Bifidobacterium and saline solution in the last 4 weeks; (4) Group H-V: Participants were placed on the HFD for 12 weeks, with high-fat modeling in the first 8 weeks and daily gastric gavage of vancomycin and saline solution in the last 4 weeks; (5) Group H-V-S: Participants followed HFD for 12 weeks, with high-fat modeling in the first 8 weeks and daily gastric gavage of vancomycin, followed by Bifidobacterium administration 2 hours later in the last 4 weeks; (6) Group H-V-D: Participants adhered to the HFD for 12 weeks, with high-fat modeling in the first 8 weeks and a daily intake of high-fat feed containing 0.2% DCA, along with one gastric gavage of vancomycin and saline solution in the last 4 weeks; and (7) Group H-V-D-S: Participants followed HFD for 12 weeks, with high-fat modeling in the first 8 weeks and a daily administration of high-fat feed containing 0.2% DCA in the last weeks, along with vancomycin (at a dose of 100 mg/kg) gavage, followed by Bifidobacterium administration 2 hours later. The Bifidobacterium gavage was conducted using a saline solution; 0.2 mL of this solution was administered each time for gavage (Figure 1). On the final day of the 12th week, the mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation and their entire colon was excised. Subsequently, the colonic tissue, located 1-2 cm from the anus, was immersed in a 4% paraformaldehyde fixative solution to prepare specimens. The remaining specimens were placed in prelabeled Eppendorf tubes and subsequently frozen at -80 °C.

The colonic tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24-48 hours. Dehydration was achieved using a graded series of alcohol concentrations, progressing from low to high. The tissue was then embedded in wax, sliced, dewaxed, stained, air-dried, and sealed before being subjected to microscopic observation using an Olympus BX 53 microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Immune staining of the colon tissue slides was performed in accordance with the instructions provided on the kit (Maixin, Fuzhou, China). Initially, colon tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by paraffin embedding, sectioning, dewaxing, and rehydration. Subsequently, antigen retrieval was conducted, along with the blocking of endogenous peroxidase and serum sealing. The blocking solution was then removed, and phosphate-buffered saline was added at a dilution of 1:500 for the F4/80 antibody, which was then blocked with 10% goat serum and rabbit serum (GB113373, Servicebio, Wuhan, China). Incubation was carried out overnight. The goat anti-rat (dilution 1:100) and goat anti-mouse (dilution 1:200, Boster, Wuhan, China) secondary antibodies were used. Following the DAB chromogenic reaction (G1212, Servicebio, Wuhan, China), microscopic observation was conducted; the color development time was carefully controlled to ensure positive results. Finally, cell nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin for 3 minutes, followed by washing, mounting, and final microscopy using Olympus BX 53 (Tokyo, Japan). F4/80-positive areas were quantified using ImageJ software. All images were processed under uniform exposure conditions with background subtraction and flat-field correction. The threshold for positive signal detection was dynamically determined based on image characteristics (typical optical density range: 0.12-0.35), using the software’s automated analysis features to ensure consistent segmentation. Five representative areas were analyzed per group, with results averaged for statistical analysis.

For the immunofluorescence analysis, embedded wax blocks were sectioned, dewaxed, and hydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed, followed by the inhibition of endogenous peroxidase. The samples were then incubated for 30 minutes. The F4/80 antibody was combined with either the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) antibody or the CD206 antibody. Following the removal of the blocking solution, primary antibodies (iNOS/F4/80 GB11119/GB113373 at 1:2000/1:500, Servicebio, Wuhan, China; CD206/F4/80 GB113497/GB113373 at 1:2000/1:500, Servicebio, Wuhan, China) were added, and the samples were incubated overnight in a wet box. Subsequently, a secondary antibody (HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG/Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (GB23303, 1:100, Servicebio, Wuhan, China) was added and incubated for 50 minutes. Afterward, tyramide signal amplification dye was applied, and the samples were placed in phosphate-buffered saline and washed three times (5 minutes each) using a color shaker, followed by the addition of tyramide signal amplification and incubation for 10 minutes. The samples were then washed three times (5 minutes each) in Tris-buffered saline with Tween to remove excess dye. For nuclear staining, DAPI dye solution (G1012, Servicebio, Wuhan, China) was added and incubated for 10 minutes. Finally, the slides were sealed and stored away from light. Images were acquired using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica, Germany). Uniform exposure time, optimum laser intensity and gain settings, and background subtraction and flat field correction were carried out for all images to ensure data consistency. The average fluorescence intensity, co-localization area, and nucleus count (DAPI labeling) were automatically calculated by using the ImageJ software to determine the threshold setting and regional segmentation rules.

A total of 5-20 mg of tissue was used to isolate total RNA using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Gibco, CA, United States), which was subsequently reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (Servicebio, Wuhan, China). The purity and concentration of the RNA were assessed using ultraviolet spectrophotometry; an A260:A280 ratio of > 1.8 was considered satisfactory. High concentrations of RNA were diluted to a final concentration of 200 ng/μL. The integrity of the RNA was verified through denaturing gel electrophoresis. The mRNA expression analysis of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-4 was conducted using the SYBR Green Master Mix kit I (Servicebio, Wuhan, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. As previously described, β-actin served as an internal control. All primer sequences are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. Real-time polymerase chain reaction was executed using the Roche LightCycler 480 (Switzerland) in a 96-well plate format. The results were quantified and analyzed with Roche LightCycler 480 software. The expression of target genes was normalized to the endogenous β-actin mRNA expression (2-ΔΔCt), and the amount of target gene in the control sample was set at 1.0.

To prepare the working standard solution, formaldehyde was diluted to the concentrations of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 ng/mL. Next, the DCA standard mother solution was prepared and stored at -20 °C. For sample processing, approximately 100 mg of the stool sample was taken, to which 300 μL of methanol was added. The mixture was vortexed and centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected, diluted tenfold, vortexed again, and centrifuged. The final supernatant was then analyzed. The liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry test was carried out using an UltiMate 3000 RS chromatograph (Thermo Fisher Scientific, China) and a Q Exactive high-resolution mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, China). Chromatogram acquisition and integration were performed using Xcalibur 4.0 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, China) for linear regression analysis with a weighted coefficient. The mass spectrometry conditions included the use of an electrospray ionization source in the negative ionization mode at 500 °C, with a voltage of -4500 V. The collision gas pressure was set at 41.37 kPa, the air curtain gas at 206.84 kPa, and both the aerosolized and auxiliary gases were set a 344.74 kPa. Scanning and data export were conducted accordingly.

DNA extraction, detection, and determination of colon contents: DNA was extracted from mouse stool, and its concentration was assessed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop detection. The DNA samples were diluted to a concentration of 1 ng/μL. The amplified template consisted of genomic DNA, with primers 343F (5’-TACGGRAGGCAGCAG-3’) and 798R (5’-AGGGTATCTAATCCT-3’) targeting the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene for polymerase chain reaction amplification. Subsequently, the samples were sent to Servicebio (Wuhan, China) for further testing.

Bioinformatics analysis: High-quality sequences were obtained through sequencing, splicing, and filtering of the original sequences. Subsequently, Vsearch software was employed to select parameters with 97% sequence similarity, facilitating the analysis of multiple operational taxonomic units (OTUs). Representative sequences of each OTU were filtered using the QIIME package and annotated against the Silva database. Various mouse strains were utilized to investigate the mouse intestinal microbiota. Alpha diversity analysis was conducted to illustrate the diversity among samples. The Wilcoxon algorithm was employed to assess the significance of differences between groups. In this study, four metrics of alpha diversity were analyzed: Ace (which measures species abundance, with a higher index indicating greater species abundance), Pielou_e (where a larger uniformity index reflects higher species uniformity), and the Shannon and Simpson indices (which measure species richness, with greater indices indicating higher species diversity). Beta diversity analysis was performed to illustrate differences in species composition among samples by primarily using principal component analysis, where the distance between samples represents their similarities and dissimilarities. A community structure histogram was generated with a default relative abundance of 100% for all species. The relative abundance percentages of the top 10 species were mapped, with larger areas representing higher species abundance. This experiment explores the relative abundance at both the phyla and genus levels.

All experiments were conducted in triplicate and were also independently repeated at least three times. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The data are presented as the mean ± SD. A one-way analysis of variance was employed to compare the average values among the three groups, followed by the appropriate least significant difference test if the homogeneity of variance was confirmed, or Dunnett’s T3 test if it was not confirmed. The threshold for statistical significance was set at a P value < 0.05.

The mice in group N remained active and vigorous during the entire experimental period. In contrast, the HFD-fed mice displayed reduced activity and oily fur at four weeks. Following drug intervention, some of these mice developed paste-like stool (types 5-7 based on the Bristol Stool Chart); however, most returned to their pre-intervention state within one week. The body weight of each group rapidly increased during the initial 8 weeks, followed by a slower increase over the subsequent 4 weeks. The H, H-S, H-V, H-V-S, H-V-D, and H-V-D-S groups demonstrated a significant increase in body weight compared to that shown by the N group (P < 0.05, n = 6). However, no significant differences in body weight were observed among the HFD groups (Figure 2A). From the fourth week onward, each group receiving HFD demonstrated a decreased food intake compared to the normal diet (N) group. This observation suggests that the HFD not only contributes to an increase in body weight but also results in a reduction in overall food consumption among the mice. This reduction is likely attributable to the higher energy density of the HFD (Figure 2B).

The hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining results for colon tissues in each group are presented in Figure 2C. Histopathological scores were obtained by randomly selecting five fields of view from each tissue section under high-power microscopy (200 ×). Statistical analysis was conducted to evaluate the severity of colon inflammation in each group of mice, as illustrated in Figure 2D. The scoring criteria are detailed in Supplementary Table 2, where the total score comprises the sum of histological infiltration and tissue damage, with a scoring range of 0-6. After conducting a histopathological evaluation, it was observed that the histopathological score of group H was significantly higher than that of group N (P < 0.05). Additionally, the scores of groups H-S, H-V, and H-V-S were significantly lower than that of group H (P < 0.05). The H-V-D group demonstrated a higher score compared to that of the H-V group (P < 0.05). Conversely, the H-V-D-S group exhibited a lower score in comparison to that of the H-V-D group (P < 0.05). The histological scores were statistically significant (aP < 0.05, n = 6). Figure 2C depicts three independent HE stains at magnifications of 200 × (scale bar: 100 μm) and 400 × (scale bar: 60 μm). The mucosal epithelium of the colonic tissue in group N mice appeared clear and intact, with glands organized in an orderly fashion and a minimal presence of inflammatory cells. In contrast, the colonic mucosal epithelium of groups H and H-V-D was less distinct, exhibiting significant infiltration of inflammatory cells in both the mucosa and submucosa. The H-S, H-V, and H-V-S groups demonstrated reduced inflammatory cell infiltration compared to that in the H group. Furthermore, colonic inflammatory cell infiltration was elevated in the H-V-D group compared to that in the H-V group, while a decrease in inflammatory cell infiltration was observed in the H-V-D-S group relative to that in the H-V-D group. Both HFD and DCA can promote the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the colon of mice, whereas vancomycin and Bifidobacterium mitigate HFD-induced intestinal inflammation.

Immunohistochemical analysis of the mouse colon tissue using the F4/80 macrophage marker showed that group N had a minimal presence of F4/80-positive macrophages, as evidenced by dark brown staining. In contrast, group H exhibited a significant increase in macrophage infiltration (P < 0.05). The H-S, H-V, and H-V-S groups showed a reduction in macrophage numbers relative to that in the H group (P < 0.05). Conversely, the H-V-D group displayed an increase in macrophage numbers compared to that in the H-V group (P < 0.05), while the H-V-D-S group showed a decrease relative to that in the H-V-D group (P < 0.05, Figure 2E and F). These results suggest that HFD or DCA promotes macrophage infiltration in the mouse intestinal tissue, a phenomenon that is effectively mitigated following treatment with vancomycin or Bifidobacterium.

We employed iNOS (a marker for M1-type macrophages) and CD206 (a marker for M2-type macrophages), along with F4/80 (a marker for mature macrophages), for immunodouble antibody staining. The expression of iNOS was found to be low in the colonic tissue macrophages of group N mice, while it was significantly higher in the macrophages of group H (P < 0.05). However, the iNOS expression levels in the H-S, H-V, and H-V-S groups were lower compared to that in the H group (P < 0.05). Notably, the iNOS expression level of macrophages in the H-V-D group was higher than that in the H-V group (P < 0.05), while that in the H-V-D-S group was lower compared to that in the H-V-D group (P < 0.05, Figure 3A and B). In contrast, macrophages in group N exhibited a high expression of CD206, while it was significantly lower in group H macrophages (P < 0.05). However, the expression levels of CD206 in the macrophages of groups H-S, H-V, and H-V-S were higher compared to that in group H (P < 0.05). The expression level of CD206 in group H-V-D decreased compared to that in group H-V (P < 0.05), while that in group H-V-D-S increased compared to that in group H-V-D (P < 0.05, Figure 3C and D). These findings suggest that HFD or DCA promotes M1-type polarization of intestinal macrophages in mice, while vancomycin or Bifidobacterium can inhibit this change.

Fecal samples from each group were collected, and their DCA content was measured using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. The results indicated that DCA levels were significantly higher in group H than they were in group N (P < 0.05). In contrast, the DCA concentration in group H-S decreased relative to that in group H. The fecal DCA content in the vancomycin-treated groups (H-V and H-V-S) was lower than that in group H (P < 0.05). Additionally, the fecal DCA content was lower in group H-V-D-S compared to that in group H-V-D (P < 0.05, Figure 4A). These findings suggest that HFD elevates the fecal DCA content in mice, while the administration of vancomycin or Bifidobacterium effectively reduces fecal DCA levels in HFD-fed mice.

Compared to group N, the expression levels of pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β) were significantly higher in group H (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively). Conversely, the expression level of the inflammatory inhibitor (IL-4) significantly decreased (P < 0.001). Compared to group H, the expression levels of pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β) were significantly lower (TNF-α: P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.01; IL-1β: P < 0.001 for all), and that of the inflammatory inhibitor (IL-4) was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in groups H-S, H-V, and H-V-S. In addition, the expression levels of pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β) were significantly higher (TNF-α: P < 0.001, IL-1β: P < 0.001) and that of the inflammatory inhibitor (IL-4) was significantly lower (P < 0.001) in the H-V-D group than they were in the H-V group. Compared to the H-V-D group, the expression levels of pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β) were lower (TNF-α: P < 0.05, IL-1β: P < 0.001) and that of the inflammatory inhibitor (IL-4) was significantly higher (P < 0.01) in the H-V-D-S group (Figure 4B-D). This indicates that HFD or DCA can promote the expression of pro-inflammatory markers in the colonic tissue of mice while simultaneously decreasing the levels of inhibitory inflammatory factors. However, vanco

Basic information of the sequencing data: A total of 43 mouse samples were collected from groups N, H, H-S, H-V, H-V-S, H-V-D, and H-V-D-S, followed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. On average, each sample yielded 106181 raw data points. After filtering, denoising, and splicing, 87337 valid data points were obtained, achieving an effective efficiency of 82.25%. Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were analyzed and singleton ASVs were removed. Ultimately, the standardized data exhibited a sequencing depth of 42636 and comprised 2487 ASVs. The specimens were subsequently sent to Wuhan Sevwell Biotechnology Co., Ltd., (Wuhan, China) for testing.

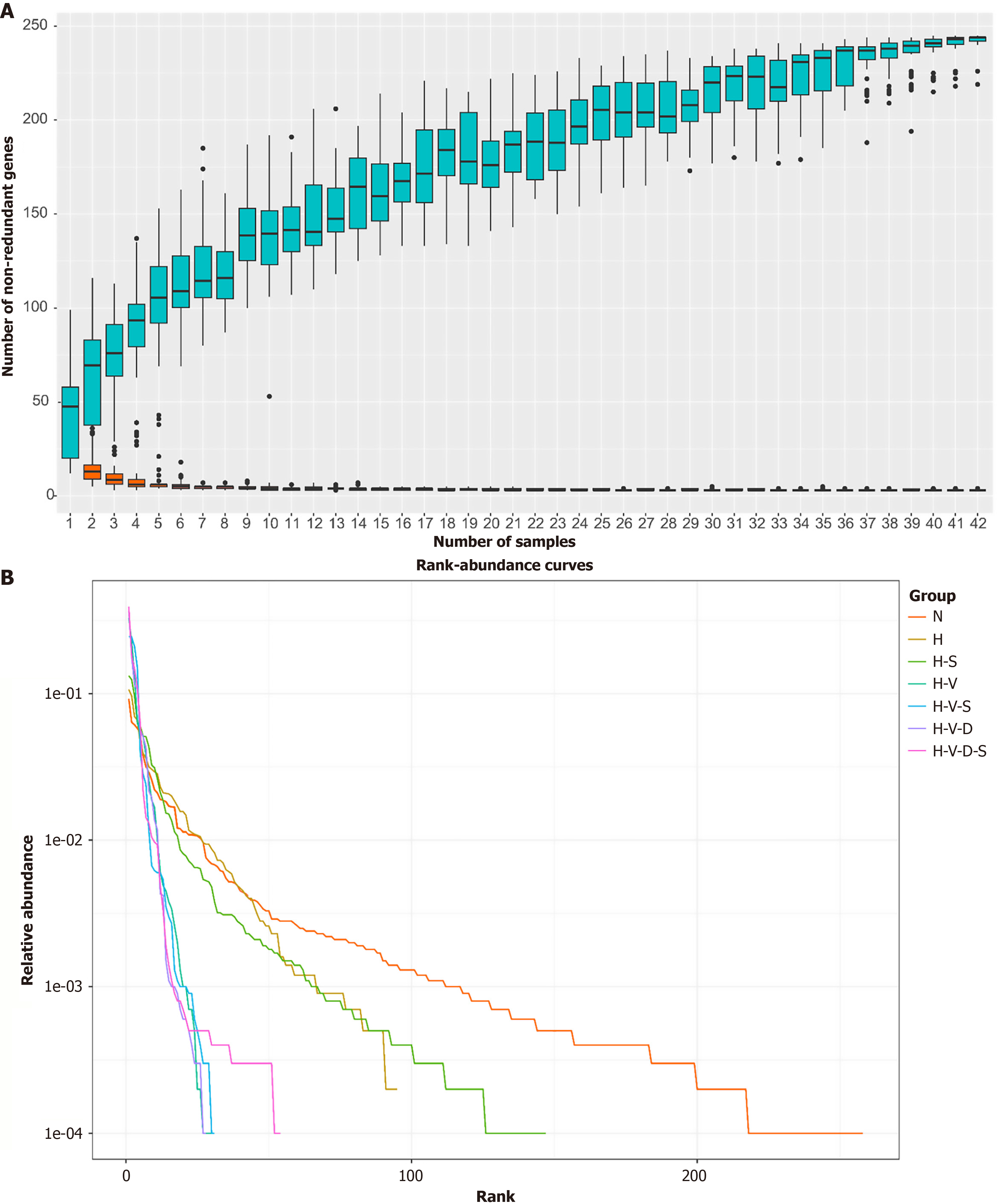

Species accumulation curve vs the rank-abundance curve analysis: The species accumulation box chart, also known as a species accumulation boxplot, is an analytical tool that illustrates the relationship between species diversity and sample size. It examines species composition, predicts species abundance, and evaluates the adequacy of the sample size. Specifically, a sharply rising curve indicates that the sample size is insufficient; conversely, a curve that rises slowly and approaches a horizontal line suggests that the increase in species richness is marginal, which in turn indicates that the sampling is adequate for subsequent data analysis. According to Figure 5A, the curve approaches a horizontal line when the sample size reaches approximately 32, demonstrating that a sample size of 42 is sufficient for this experiment.

The rank-abundance curve illustrates the richness and uniformity of species within the sample by ranking the OTUs according to their relative abundance. For constructing a rank-abundance curve, the rank number of the OTUs is plotted on the abscissa, while their relative abundance is plotted on the ordinate. A higher species richness corresponds to a greater horizontal span of the curve, while a gentler curve indicates a more uniform distribution of species. As depicted in Figure 5B, the N group exhibits the gentlest curve and the maximum abscissa span, suggesting that it possesses the highest species richness and the most even distribution of species. Conversely, group H demonstrates a significant decrease in both species richness and evenness compared to group N. Notably, the H-S group shows an increase in species richness and evenness relative to those in the H group. The horizontal axis spans of groups H-V, H-V-S, H-V-D, and H-V-D-S, which were administered vancomycin, significantly decreased, resulting in much steeper curves that indicate lower species diversity and uniformity. Notably, the H-V-S and H-V-D-S groups, which contain Bifidobacterium, display slightly flatter curves compared to those in the H-V and H-V-D groups, with a marginally wider transverse axis span. Thus, HFD can diminish the species richness and uniformity of the mouse intestinal flora, whereas Bifidobacterium can partially mitigate this effect, enhancing the species richness and uniformity of the intestinal flora in HFD-fed mice. Additionally, vancomycin significantly reduces the species richness and uniformity of mouse intestinal flora, although Bifidobacterium may offer some improvement in this regard.

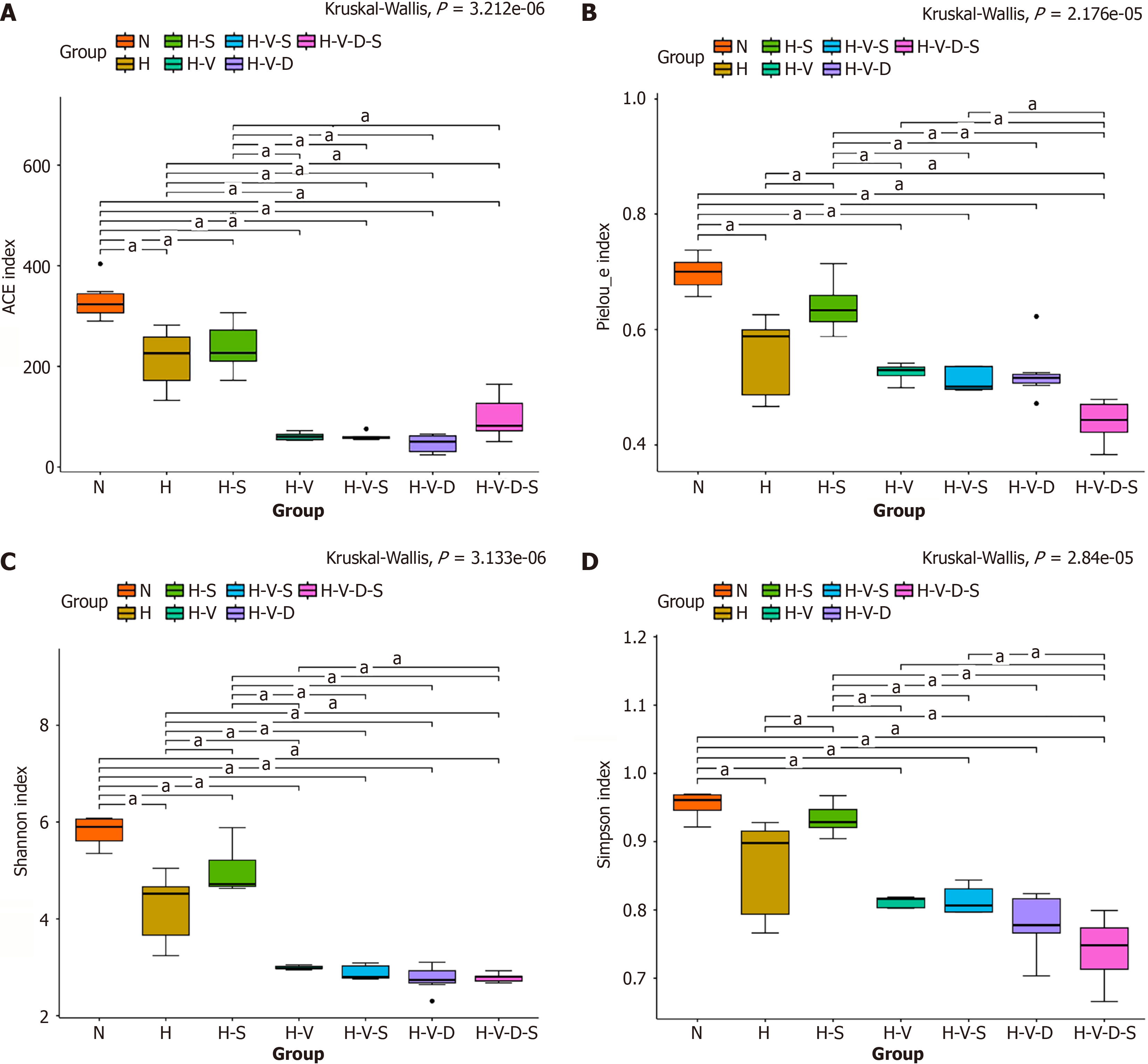

Effects of Bifidobacterium and vancomycin on microbial alpha diversity in the mouse colon: Alpha diversity represents the species diversity within a specific sample. Diversity analysis reveals both species abundance and diversity in a single sample. Alpha diversity can be measured through various indices, such as Chao1, Ace, Shannon, Simpson, Pielou_e, and Coverage. The Chao1 and Ace indices are for specifically gauging species abundance, which is the count of species present in a sample. In contrast, the Shannon and Simpson indices evaluate species diversity; a higher index value signifies greater diversity within the sample. The Pielou_e index assesses species evenness, with larger values indicating a higher level of evenness among species.

As depicted in Figure 6A, the Ace index in group H mice showed a significant decrease compared to that in the N group (P < 0.05). In contrast, the increase in the Ace index observed in H-S mice compared to that in group H mice was not statistically significant. Furthermore, the Ace index in H-V, H-V-S, H-V-D, and H-V-D-S mice treated with vancomycin also exhibited a significant decrease compared to that in the N group (P < 0.05). However, no statistically significant increase in the Ace index was noted in the H-V-S group when compared to that in the H-V group. Additionally, the Ace index of mice in the H-V-D-S group showed an increase when compared to that in the H-V-D group. Thus, we can suggest that HFD reduces the species abundance of mouse intestinal flora, and Bifidobacterium does not mitigate this effect. Moreover, vancomycin further diminishes the species abundance of mouse intestinal flora, which does not improve even after the addition of Bifidobacterium.

As depicted in Figure 6B, the Pielou_e index of group H mice was significantly lower than that of the N group mice (P < 0.05). Conversely, the Pielou_e index of the H-S group mice was higher than that of group H mice (P < 0.05). Additionally, in the presence of vancomycin, the Pielou_e index of the H-V, H-V-S, H-V-D, and H-V-D-S groups became lower compared to that of the N group (P < 0.05). However, the increase in the Pielou_e index of the H-V-S group was not statistically significant compared to that of the H-V group. Similarly, the increase in the Pielou_e index of the H-V-D-S group was not statistically significant compared to that of the H-V-D group. These results indicate that the HFD diminishes the species uniformity of the intestinal flora in mice, an effect mitigated by the addition of Bifidobacterium. Vancomycin also decreases the species uniformity of mouse intestinal flora, which, however, is not counteracted by the addition of Bifidobacterium.

As shown in Figure 6C and D, both the Shannon and Simpson indexes were significantly lower in group H mice than they were in the N group (P < 0.05). In contrast, they were higher in the H-S group than they were in group H (P < 0.05). Additionally, mice in the H-V, H-V-S, H-V-D, and H-V-D-S groups, which received vancomycin, exhibited lower Shannon and Simpson indexes than their corresponding values in the N group (P < 0.05). Notably, there was no statistically significant increase in the Shannon and Simpson indexes in the H-V-S group mice that received Bifidobacterium compared to that in the H-V group mice. Furthermore, the Ace index of the H-V-D-S group mice was higher than that of the H-V-D group mice. These results indicate that HFD can significantly reduce the species diversity of intestinal flora in mice. However, this reduction can be mitigated by the inclusion of Bifidobacterium. While vancomycin can decrease the species diversity of mouse intestinal flora, the improvement observed upon the addition of Bifidobacterium was not significant.

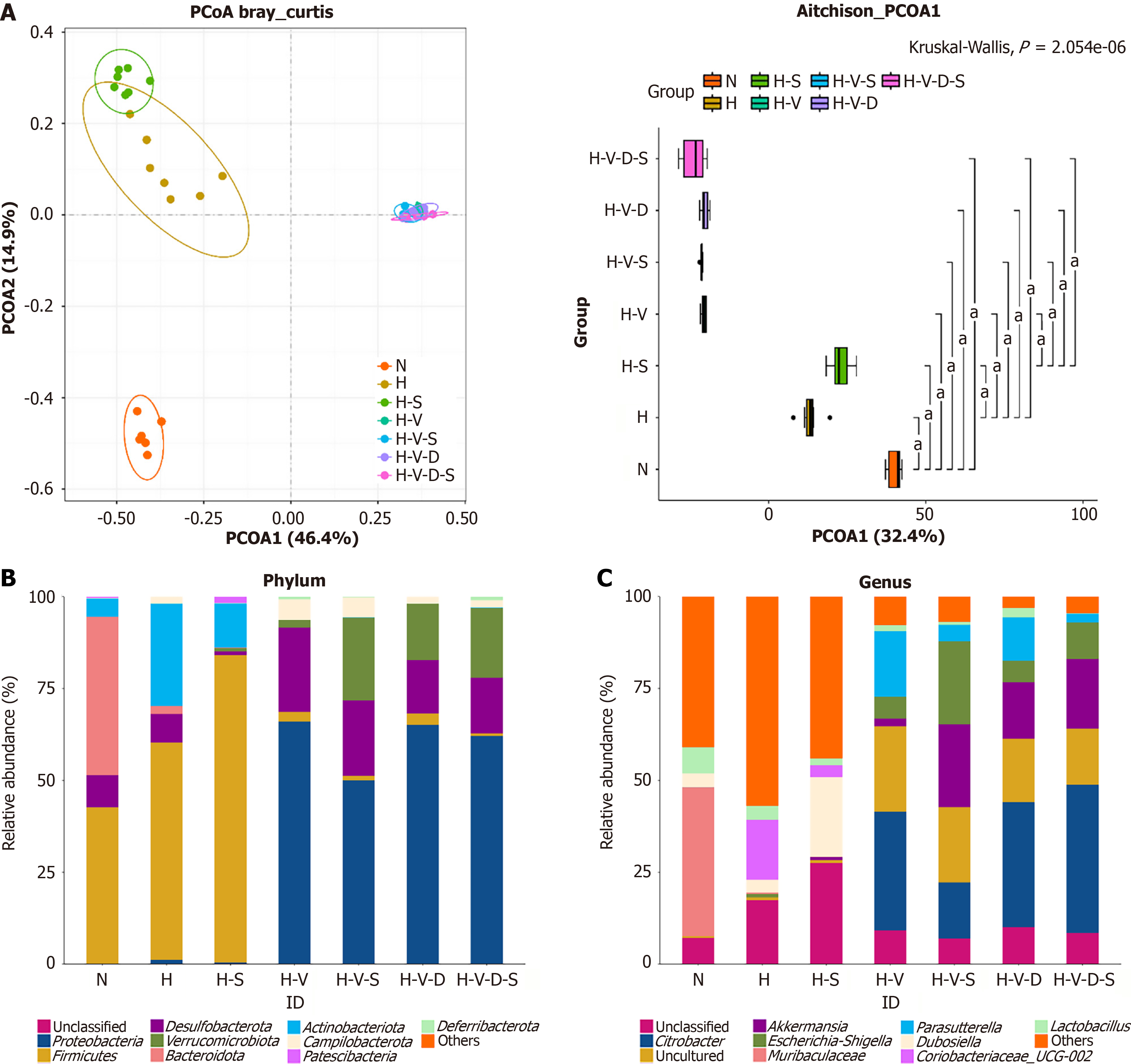

Effects of Bifidobacterium and vancomycin on microbial beta diversity in mouse colon: Beta diversity analysis evaluates the similarity among different samples in terms of species diversity. Principal coordinate analysis is used to distill the most significant elements and structures from multidimensional data by leveraging feature values and arranging feature vectors. In principal coordinate analysis, the principal coordinate combination with the highest contribution rate is chosen for visualization. Closer proximity between the samples signifies greater similarity in species composition, whereas a greater distance indicates a more distinct species composition.

As shown in Figure 7A, seven groups of 42 samples correspond to 42 distinct points. Each group is marked by a unique color. The confidence ellipse for each group is drawn using the color of the respective group. Notably, group N is positioned far from the other groups, indicating a significant variation in species composition between group N and that of the others (P < 0.05). Group H is positioned far from the H-S, H-V, H-V-S, H-V-D, and H-V-D-S groups, showing a significant variation in species composition between group H and the others (P < 0.05). Group H-S is positioned far from the H-V, H-V-S, H-V-D, and H-V-D-S groups, showing a significant variation in species composition between group H-S and the others (P < 0.05). The remaining four groups, H-V, H-V-S, H-V-D, and H-V-D-S, which were supplemented with vancomycin, are nearly indistinguishable in their locations, indicating a high similarity in their species composition structures (P > 0.05). Thus, HFD can alter the species composition of the intestinal microflora in mice. Bifidobacterium can also influence the species composition of mouse intestinal microflora under HFD. However, vancomycin can change the species composition of the mouse gut flora, which was not evident upon the addition of Bifidobacterium.

Analysis of the effects of Bifidobacterium and vancomycin on species diversity in the colon of mice: At the phylum classification level, as depicted in Figure 7B, the intestinal flora of group N mice was primarily composed of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, with a total relatively high abundance of approximately 85.76%. In contrast, the intestinal flora of groups H and H + S was predominantly made up of Firmicutes and Actinobacteriota, comprising approximately 86.93% and 95.69%, respectively, of the intestinal flora of these two groups. The H-V-S, H-V-D, and H-V-D-S groups primarily consisted of Proteobacteria, Desulfobacterota, and Verrucomicrobiota, comprising approximately 92.99%, 96.21%, and 94.96%, respectively. The intestinal microbiota of H-V mice mainly comprised Proteobacteria and Desulfobacterota, with a com

At the genus level, as illustrated in Figure 7C, the intestinal microflora of group N mice was predominantly composed of Muribaculaceae and Lactobacillus. In contrast, the intestinal microbiota of mice in the H-V, H-V-S, H-V-D, and H-V-D-S groups was primarily constituted of Citrobacter, Akkermansia, and Escherichia-Shigella. The intestinal flora of mice in groups H and H-S mainly comprised Citrobacter, Dubosiella, and Lactobacillus. Compared to the N group, group H exhibited a significant decrease in Muribaculaceae, Parasutterella, and Lactobacillus (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, and P < 0.05, respectively). Furthermore, in comparison to group H, the H-S group showed an increase in Akkermansia and Dubosiella (P < 0.01), while the H-V group exhibited a significant increase in Citrobacter, Akkermansia, Escherichia-Shigella, and Parasutterella (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively) and a decrease in Muribaculaceae and Dubosiella (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively). A comparison of the H-V group with the H-V-S group demonstrated a notable reduction in Citrobacter and Parasutterella (P < 0.01) and an increase in the Akkermansia and Escherichia-Shigella levels in the latter (P < 0.01). Furthermore, in comparison to the H-V-D group, the H-V-D-S group demonstrated a significant increase in Escherichia-Shigella (P < 0.05) and a decrease in the Parasutterella and Lactobacillus levels, although not to the extent of P < 0.01 or P < 0.05. Hence, we can suggest that an HFD can alter the relative abundance of intestinal microflora in mice at both the phylum and genus levels. This alteration can be partially inhibited by Bifidobacterium or vancomycin.

HFD is a significant risk factor for various chronic diseases, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, gastrointestinal disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. The HFD increases the risk factor for these diseases mainly through the dysbiosis of gut microbiota, disruption of the intestinal barrier, inflammation, increased oxidative stress, metabolic endotoxemia, and insulin resistance[7,25-29]. Long-term consumption of HFDs can impair mitochondrial bioenergetics in the colon epithelial cells of obese mice, leading to an increased production of oxygen and nitrate by intestinal cells, promoting the catabolism of choline by Escherichia coli, and elevating the levels of trimethylamine N-oxide, a harmful metabolite in circulation that promotes the onset of cardiovascular disease[26]. Microbiota-mediated LPS may activate the TLR4/NF-κB pathway, inhibiting the expression levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, cAMP response element-binding protein, and synapsin-1, thereby further exacerbating HFD-induced chronic diseases[30,31]. A persistent HFD can induce sustained low-level inflammation in the gut, alter the structure of gut microbiota, and lead to low-level inflammation in the brain, thereby affecting the cholinergic system[32,33]. Such a diet, particularly one rich in saturated fats, significantly modifies the structure of the gut microbiota in mice, markedly reducing diversity while significantly increasing the abundance of bile-tolerant gut bacteria. This alteration results in an imbalance between Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, promoting the proliferation of pro-inflammatory bacteria, such as Desulfovibrio, while diminishing anti-inflammatory bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. This study showed that, compared to the control group, the HFD group exhibited an increased relative abundance of Firmicutes and a decreased relative abundance of Bacteroidetes, alongside reduced species richness and evenness of the gut microbiota in mice. The addition of Bifidobacterium can partially inhibit these changes. Thus, HFD induces alterations in the quantity and composition of gut microbiota in mice, leading to the dysbiosis of the gut microbiome, which subsequently promotes gastrointestinal inflammation[34]. This result indicates that HFD may contribute to the development of intestinal inflammation by modifying the structure of gut microbiota.

An HFD induces microbial imbalance, resulting in an increased release of LPS by gram-negative bacteria. This phenomenon disrupts the expression of tight junction proteins, such as occludin, claudin, and ZO-1, thereby enhancing intestinal permeability and facilitating the translocation of bacteria and toxins into the submucosal layer of the intestine. Additionally, this diet reduces the secretion of mucin, particularly MUC2, by goblet cells, which weakens the mucus barrier and elevates the risk of pathogen contact with epithelial cells. Furthermore, it induces mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress in intestinal epithelial cells, leading to a reduction in antioxidant substances, including glutathione and superoxide dismutase. This cascade accelerates cell death, further compromising barrier integrity and increasing the intestinal permeability. Consequently, LPS and other inflammatory substances enter the bloodstream, stimulating immune responses and intestinal inflammation, which activate systemic inflammatory responses through the damaged intestinal barrier. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns, such as LPS, activate macrophages and dendritic cells via the TLR4/NF-κB pathway, releasing pro-inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, while concurrently reducing the expression of anti-inflammatory factors, like IL-10, IL-17, and IL-22, thereby indirectly increasing intestinal permeability[8,35,36]. HFD-induced insulin resistance disrupts gut metabolism via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mechanistic target of rapamycin pathway, while adipose-derived M1 macrophages systemically propagate gut inflammation[37].

Gut dysbiosis induces DCA, promoting M1 macrophage polarization via TLRs and exacerbating inflammatory tissue damage[12]. In this experimental study, the expression level of iNOS was found to be elevated, while that of CD206 decreased in the colon tissues of mice in the high-fat group, promoting the polarization of intestinal macrophages toward the M1 phenotype. Concurrently, the expression levels of pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α and IL-1β) increased in the high-fat group, while that of the anti-inflammatory factor IL-4 significantly decreased. The chronic inflammation induced by this M1 polarization further disrupts the balance within the gut, potentially resulting in systemic dysregulation. Therefore, therapeutic strategies targeting macrophage polarization, such as dietary regulation or the use of specific metabolites, may be critical for mitigating the adverse effects of HFD and promoting gut health.

HFD-induced dysbiosis reduces SCFAs (e.g., butyrate) and promotes pathogenic overgrowth, inflammatory mediators, and barrier dysfunction[38,39]. A concurrent rise in harmful metabolites such as DCA induces cytotoxicity and disrupts mitochondria and tight junctions, which increases intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”)[35,40]. DCA triggers inflammation via TLR4/NF-κB and NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3/IL-1β pathways and promotes the activation of the IL-23/Th17/IL-17 axis[12-14,41,42]. It further affects bile acid metabolism mediated by the gut microbiota by inhibiting farnesoid X receptors and activating TGR5-mediated signaling, resulting in weakened anti-inflammatory and barrier repair signals, thus inducing oxidative stress and DNA damage, which exacerbates inflammation[29,43]. This study found that the DCA content in feces significantly increased following HFD. Moreover, the H-V-D group, which received added DCA, exhibited highly consistent expression of inflammatory markers in HE staining, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and inflammatory factor detection in mouse colon tissue compared to the levels shown by IBD models. This result indicates that an HFD can increase secondary bile acids in the gut, which in turn induce and exacerbate intestinal inflammation in mice. Supplementing DCA in mice treated with vancomycin further intensifies the infiltration of pro-inflammatory macrophages and exacerbates colonic inflammation.

Bifidobacterium treats inflammation by generating SCFAs that activate G protein-coupled receptor 41/43 and inhibit NF-κB to promote mucosal healing. It also adheres to the mucosa, forming a protective barrier against pathogens and restoring healthy gut microbiota to enhance intestinal barrier function[44-46]. Bifidobacterium strengthens the intestinal barrier function by upregulating MUC2 mucin and key tight junction proteins (ZO-1, occludin, and claudin-1). Its extracellular vesicles stimulate goblet cell proliferation and support mucosal repair. By inhibiting NF-κB and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling, it reduces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β) while promoting Treg expansion and the production of anti-inflammatory factors (IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β). The metabolite indole-3-lactic acid induces M2 macrophage polarization. Additionally, Bifidobacterium activates the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 pathway and decreases malondialdehyde levels, ameliorating oxidative stress[44,47-51]. Our experiment demonstrated that Bifidobacterium reduces DCA levels and independently influences M1 polarization, or indirectly affects M1 polarization by reducing DCA. However, the specific mechanism through which Bifidobacterium reduces DCA is yet to be further verified.

Vancomycin, a narrow-spectrum tetracycline antibiotic, is primarily used against severe gram-positive infections, including Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus[52,53]. It significantly disrupts gut microbiota by reducing microbial diversity, altering bile acid metabolism, and diminishing SCFA production, ultimately promoting metabolic disorders and inflammation[54,55]. In this study, the administration of vancomycin lowered species richness, abundance, and evenness of the gut microbiota compared to those in the control group, indicating that vancomycin can induce an imbalance in the gut microbiota. Furthermore, vancomycin selectively inhibits the recruitment of monocytes/macrophages, thereby significantly alleviating the severity of colitis[56]. This finding aligns with the observed reduction in the DCA content of mouse feces and the decrease in inflammatory markers in the lipid fraction following vancomycin administration. While various studies have indicated that Bifidobacterium can enhance gut function post-antibiotic treatment, our experimental results revealed that Bifidobacterium did not lead to an increase in gut microbiota richness or abundance following vancomycin administration. This may be attributable to the concurrent administration of vancomycin and Bifidobacterium or the prolonged use of vancomycin, which may have inhibited the ability of Bifidobacterium to effectively restore gut microbiota. The metabolites produced by Bifidobacteria in the gut, such as acetic acid, lactic acid, and succinic acid, may serve as nutrient sources for Escherichia-Shigella bacteria, which are gram-negative and typically resistant to vancomycin. Bifidobacteria can dissociate conjugated bile acids, such as the primary forms of DCA, into free bile acids, potentially creating an environment that favors Escherichia-Shigella over other bacterial species. Although the levels of Salmonella paratoxinoids decreased, this reduction was not statistically significant. These bacteria exhibit strong tolerance; they are resistant to both vancomycin and bile acids, maintain population stability, and are minimally affected by Bifidobacteria. Similarly, the levels of Lactobacillus also decreased, though not significantly. The baseline levels were extremely low because of extensive vancomycin sterilization; no statistically significant decline was observed. This phenomenon highlights the context-dependent effects of Bifidobacteria, indicating that their efficacy is not absolute. In certain scenarios, unexpected or even counterproductive results may arise.

HFD and DCA can promote the infiltration of colonic macrophages in mice and their polarization to the M1 type. This effect can be inhibited by vancomycin or Bifidobacterium. The HFD increases the DCA content in the feces of mice, which, however, can be reduced by using either vancomycin or Bifidobacterium. Hence, both vancomycin and Bifidobacterium can be employed to decrease the infiltration of pro-inflammatory macrophages and colitis in the colon. Notably, the infiltration of pro-inflammatory macrophages and colitis is exacerbated in mice treated with vancomycin following DCA supplementation. Furthermore, Bifidobacterium improves microbiota richness and evenness but does not restore the overall abundance (Ace index), particularly in HFD- or vancomycin-treated groups. Overall, HFD alters the relative abundance of intestinal flora in mice at both the phylum and genus levels, while Bifidobacterium or vancomycin can partially inhibit these changes. We believe these findings may provide a theoretical rationale for using probiotics in treating intestinal inflammation associated with HFD-induced elevated DCA levels. Future probiotic applications should focus on targeted therapies using next-generation and engineered strains for conditions such as metabolic disorders, cancer immunotherapy, and mental health. Dietary strategies should incorporate precision probiotics and prebiotics tailored to individual microbiome profiles. Clinically advanced trials should be explored to define and identify microbial consortia and their mechanisms of action, which may help in accelerating their translation into evidence-based treatments for a wider range of diseases.

| 1. | Lau HCH, Zhang X, Yu J. Gut microbiota and immune alteration in cancer development: implication for immunotherapy. eGastroenterology. 2023;1:e100007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Allam-Ndoul B, Castonguay-Paradis S, Veilleux A. Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Trans-Epithelial Permeability. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Khan Mirzaei M, Deng L. Sustainable Microbiome: a symphony orchestrated by synthetic phages. Microb Biotechnol. 2021;14:45-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Danne C, Skerniskyte J, Marteyn B, Sokol H. Neutrophils: from IBD to the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;21:184-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Khuu MP, Paeslack N, Dremova O, Benakis C, Kiouptsi K, Reinhardt C. The gut microbiota in thrombosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2025;22:121-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, Burcelin R. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2008;57:1470-1481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3224] [Cited by in RCA: 3622] [Article Influence: 201.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kangwan N, Pratchayasakul W, Kongkaew A, Pintha K, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn SC. Perilla Seed Oil Alleviates Gut Dysbiosis, Intestinal Inflammation and Metabolic Disturbance in Obese-Insulin-Resistant Rats. Nutrients. 2021;13:3141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Malesza IJ, Malesza M, Walkowiak J, Mussin N, Walkowiak D, Aringazina R, Bartkowiak-Wieczorek J, Mądry E. High-Fat, Western-Style Diet, Systemic Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota: A Narrative Review. Cells. 2021;10:3164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 99.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kawano Y, Nakae J, Watanabe N, Kikuchi T, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kaneko M, Abe T, Onodera M, Itoh H. Colonic Pro-inflammatory Macrophages Cause Insulin Resistance in an Intestinal Ccl2/Ccr2-Dependent Manner. Cell Metab. 2016;24:295-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Levy M, Thaiss CA, Elinav E. Metabolites: messengers between the microbiota and the immune system. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1589-1597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nagathihalli NS, Beesetty Y, Lee W, Washington MK, Chen X, Lockhart AC, Merchant NB. Novel mechanistic insights into ectodomain shedding of EGFR Ligands Amphiregulin and TGF-α: impact on gastrointestinal cancers driven by secondary bile acids. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2062-2072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang L, Gong Z, Zhang X, Zhu F, Liu Y, Jin C, Du X, Xu C, Chen Y, Cai W, Tian C, Wu J. Gut microbial bile acid metabolite skews macrophage polarization and contributes to high-fat diet-induced colonic inflammation. Gut Microbes. 2020;12:1-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhao S, Gong Z, Zhou J, Tian C, Gao Y, Xu C, Chen Y, Cai W, Wu J. Deoxycholic Acid Triggers NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Aggravates DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice. Front Immunol. 2016;7:536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li D, Zhou J, Wang L, Gong Z, Le H, Huang Y, Xu C, Tian C, Cai W, Wu J. Gut microbial metabolite deoxycholic acid facilitates Th17 differentiation through modulating cholesterol biosynthesis and participates in high-fat diet-associated colonic inflammation. Cell Biosci. 2023;13:186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Stenman LK, Holma R, Korpela R. High-fat-induced intestinal permeability dysfunction associated with altered fecal bile acids. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:923-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Farabegoli F, Santaclara FJ, Costas D, Alonso M, Abril AG, Espiñeira M, Ortea I, Costas C. Exploring the Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Inulin by Integrating Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analyses in a Murine Macrophage Cell Model. Nutrients. 2023;15:859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Park MA, Park M, Jang HJ, Lee SH, Hwang YM, Park S, Shin D, Kim Y. Anti-inflammatory potential via the MAPK signaling pathway of Lactobacillus spp. isolated from canine feces. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0299792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hao R, Liu Q, Wang L, Jian W, Cheng Y, Zhang Q, Hayer K, Kamarudin Raja Idris R, Zhang Y, Lu H, Tu Z. Anti-inflammatory effect of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum T1 cell-free supernatants through suppression of oxidative stress and NF-κB- and MAPK-signaling pathways. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2023;89:e0060823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Xu Y, Ding X, Wang Y, Li D, Xie L, Liang S, Zhang Y, Li W, Fu A, Zhan X. Bacterial Metabolite Reuterin Attenuated LPS-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Response in HD11 Macrophages. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11:1662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Magryś A, Pawlik M. Postbiotic Fractions of Probiotics Lactobacillus plantarum 299v and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Show Immune-Modulating Effects. Cells. 2023;12:2538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hradicka P, Beal J, Kassayova M, Foey A, Demeckova V. A Novel Lactic Acid Bacteria Mixture: Macrophage-Targeted Prophylactic Intervention in Colorectal Cancer Management. Microorganisms. 2020;8:387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Foley MH, Walker ME, Stewart AK, O'Flaherty S, Gentry EC, Patel S, Beaty VV, Allen G, Pan M, Simpson JB, Perkins C, Vanhoy ME, Dougherty MK, McGill SK, Gulati AS, Dorrestein PC, Baker ES, Redinbo MR, Barrangou R, Theriot CM. Bile salt hydrolases shape the bile acid landscape and restrict Clostridioides difficile growth in the murine gut. Nat Microbiol. 2023;8:611-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hernández-Gómez JG, López-Bonilla A, Trejo-Tapia G, Ávila-Reyes SV, Jiménez-Aparicio AR, Hernández-Sánchez H. In Vitro Bile Salt Hydrolase (BSH) Activity Screening of Different Probiotic Microorganisms. Foods. 2021;10:674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shiver AL, Sun J, Culver R, Violette A, Wynter C, Nieckarz M, Mattiello SP, Sekhon PK, Bottacini F, Friess L, Carlson HK, Wong DPGH, Higginbottom S, Weglarz M, Wang W, Knapp BD, Guiberson E, Sanchez J, Huang PH, Garcia PA, Buie CR, Good BH, DeFelice B, Cava F, Scaria J, Sonnenburg JL, Van Sinderen D, Deutschbauer AM, Huang KC. Genome-scale resources in the infant gut symbiont Bifidobacterium breve reveal genetic determinants of colonization and host-microbe interactions. Cell. 2025;188:2003-2021.e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen J, Xiao Y, Li D, Zhang S, Wu Y, Zhang Q, Bai W. New insights into the mechanisms of high-fat diet mediated gut microbiota in chronic diseases. Imeta. 2023;2:e69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yoo W, Zieba JK, Foegeding NJ, Torres TP, Shelton CD, Shealy NG, Byndloss AJ, Cevallos SA, Gertz E, Tiffany CR, Thomas JD, Litvak Y, Nguyen H, Olsan EE, Bennett BJ, Rathmell JC, Major AS, Bäumler AJ, Byndloss MX. High-fat diet-induced colonocyte dysfunction escalates microbiota-derived trimethylamine N-oxide. Science. 2021;373:813-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Laurans L, Mouttoulingam N, Chajadine M, Lavelle A, Diedisheim M, Bacquer E, Creusot L, Suffee N, Esposito B, Melhem NJ, Le Goff W, Haddad Y, Paul JL, Rainteau D, Tedgui A, Ait-Oufella H, Zitvogel L, Sokol H, Taleb S. An obesogenic diet increases atherosclerosis through promoting microbiota dysbiosis-induced gut lymphocyte trafficking into the periphery. Cell Rep. 2023;42:113350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Du W, Zou ZP, Ye BC, Zhou Y. Gut microbiota and associated metabolites: key players in high-fat diet-induced chronic diseases. Gut Microbes. 2025;17:2494703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ding L, Yang Q, Zhang E, Wang Y, Sun S, Yang Y, Tian T, Ju Z, Jiang L, Wang X, Wang Z, Huang W, Yang L. Notoginsenoside Ft1 acts as a TGR5 agonist but FXR antagonist to alleviate high fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:1541-1554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wang N, Li C, Zhang Z. Arctigenin ameliorates high-fat diet-induced metabolic disorders by reshaping gut microbiota and modulating GPR/HDAC3 and TLR4/NF-κB pathways. Phytomedicine. 2024;135:156123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Miranda CS, Santana-Oliveira DA, Vasques-Monteiro IL, Dantas-Miranda NS, Glauser JSO, Silva-Veiga FM, Souza-Mello V. Time-dependent impact of a high-fat diet on the intestinal barrier of male mice. World J Methodol. 2024;14:89723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Guo Y, Zhu X, Zeng M, Qi L, Tang X, Wang D, Zhang M, Xie Y, Li H, Yang X, Chen D. A diet high in sugar and fat influences neurotransmitter metabolism and then affects brain function by altering the gut microbiota. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Arnone D, Vallier M, Hergalant S, Chabot C, Ndiaye NC, Moulin D, Aignatoaei AM, Alberto JM, Louis H, Boulard O, Mayeur C, Dreumont N, Peuker K, Strigli A, Zeissig S, Hansmannel F, Chamaillard M, Kökten T, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Long-Term Overconsumption of Fat and Sugar Causes a Partially Reversible Pre-inflammatory Bowel Disease State. Front Nutr. 2021;8:758518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Murakami Y, Tanabe S, Suzuki T. High-fat Diet-induced Intestinal Hyperpermeability is Associated with Increased Bile Acids in the Large Intestine of Mice. J Food Sci. 2016;81:H216-H222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tan R, Dong H, Chen Z, Jin M, Yin J, Li H, Shi D, Shao Y, Wang H, Chen T, Yang D, Li J. Intestinal Microbiota Mediates High-Fructose and High-Fat Diets to Induce Chronic Intestinal Inflammation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:654074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Liu L, Xu J, Xu X, Mao T, Niu W, Wu X, Lu L, Zhou H. Intestinal Stem Cells Damaged by Deoxycholic Acid via AHR Pathway Contributes to Mucosal Barrier Dysfunction in High-Fat Feeding Mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:15578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Leng J, Chen MH, Zhou ZH, Lu YW, Wen XD, Yang J. Triterpenoids-Enriched Extract from the Aerial Parts of Salvia miltiorrhiza Regulates Macrophage Polarization and Ameliorates Insulin Resistance in High-Fat Fed Mice. Phytother Res. 2017;31:100-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Xu F, Yu Z, Liu Y, Du T, Yu L, Tian F, Chen W, Zhai Q. A High-Fat, High-Cholesterol Diet Promotes Intestinal Inflammation by Exacerbating Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis and Bile Acid Disorders in Cholecystectomy. Nutrients. 2023;15:3829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Chen H, Wang SH, Li HL, Zhou XB, Zhou LW, Chen C, Mansell T, Novakovic B, Saffery R, Baker PN, Han TL, Zhang H. The attenuation of gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids elevates lipid transportation through suppression of the intestinal HDAC3-H3K27ac-PPAR-γ axis in gestational diabetes mellitus. J Nutr Biochem. 2024;133:109708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Rawat M, Nighot M, Al-Sadi R, Gupta Y, Viszwapriya D, Yochum G, Koltun W, Ma TY. IL1B Increases Intestinal Tight Junction Permeability by Up-regulation of MIR200C-3p, Which Degrades Occludin mRNA. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1375-1389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Tian S, Wang J, Gao R, Zhao F, Wang J, Zhu W. Galacto-Oligosaccharides Alleviate LPS-Induced Immune Imbalance in Small Intestine through Regulating Gut Microbe Composition and Bile Acid Pool. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71:17615-17626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Oleszycka E, O'Brien EC, Freeley M, Lavelle EC, Long A. Bile acids induce IL-1α and drive NLRP3 inflammasome-independent production of IL-1β in murine dendritic cells. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1285357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Xu M, Shen Y, Cen M, Zhu Y, Cheng F, Tang L, Zheng X, Kim JJ, Dai N, Hu W. Modulation of the Gut Microbiota-farnesoid X Receptor Axis Improves Deoxycholic Acid-induced Intestinal Inflammation in Mice. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:1197-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Yang M, Jiang Z, Zhou L, Chen N, He H, Li W, Yu Z, Jiao S, Song D, Wang Y, Jin M, Lu Z. 3'-Sialyllactose and B. infantis synergistically alleviate gut inflammation and barrier dysfunction by enriching cross-feeding bacteria for short-chain fatty acid biosynthesis. Gut Microbes. 2025;17:2486512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Li B, Ding M, Liu X, Zhao J, Ross RP, Stanton C, Yang B, Chen W. Bifidobacterium breve CCFM1078 Alleviates Collagen-Induced Arthritis in Rats via Modulating the Gut Microbiota and Repairing the Intestinal Barrier Damage. J Agric Food Chem. 2022;70:14665-14678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Xu B, Liang S, Zhao J, Li X, Guo J, Xin B, Li B, Huo G, Ma W. Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis XLTG11 improves antibiotic-related diarrhea by alleviating inflammation, enhancing intestinal barrier function and regulating intestinal flora. Food Funct. 2022;13:6404-6418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Li Y, Li Q, Yuan R, Wang Y, Guo C, Wang L. Bifidobacterium breve-derived indole-3-lactic acid ameliorates colitis-associated tumorigenesis by directing the differentiation of immature colonic macrophages. Theranostics. 2024;14:2719-2735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Nie X, Li Q, Ji H, Zhang S, Wang Y, Xie J, Nie S. Bifidobacterium longum NSP001-derived extracellular vesicles ameliorate ulcerative colitis by modulating T cell responses in gut microbiota-(in)dependent manners. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2025;11:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Chen Y, Yang B, Stanton C, Ross RP, Zhao J, Zhang H, Chen W. Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum Ameliorates DSS-Induced Colitis by Maintaining Intestinal Mechanical Barrier, Blocking Proinflammatory Cytokines, Inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB Signaling, and Altering Gut Microbiota. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69:1496-1512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Sung WW, Lin YY, Huang SD, Cheng HL. Exopolysaccharides of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Amy-1 Mitigate Inflammation by Inhibiting ERK1/2 and NF-κB Pathways and Activating p38/Nrf2 Pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:10237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Vitheejongjaroen P, Kasorn A, Puttarat N, Loison F, Taweechotipatr M. Bifidobacterium animalis MSMC83 Improves Oxidative Stress and Gut Microbiota in D-Galactose-Induced Rats. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11:2146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Liu EW, Schwartz BS, Hysmith ND, DeVincenzo JP, Larson DT, Maves RC, Palazzi DL, Meyer C, Custodio HT, Braza MM, Al Hammoud R, Rao S, Qvarnstrom Y, Yabsley MJ, Bradbury RS, Montgomery SP. Rat Lungworm Infection Associated with Central Nervous System Disease - Eight U.S. States, January 2011-January 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:825-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Singh S, Moudgil A, Mishra N, Das S, Mishra P. Vancomycin functionalized WO(3) thin film-based impedance sensor for efficient capture and highly selective detection of Gram-positive bacteria. Biosens Bioelectron. 2019;136:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Vrieze A, Out C, Fuentes S, Jonker L, Reuling I, Kootte RS, van Nood E, Holleman F, Knaapen M, Romijn JA, Soeters MR, Blaak EE, Dallinga-Thie GM, Reijnders D, Ackermans MT, Serlie MJ, Knop FK, Holst JJ, van der Ley C, Kema IP, Zoetendal EG, de Vos WM, Hoekstra JB, Stroes ES, Groen AK, Nieuwdorp M. Impact of oral vancomycin on gut microbiota, bile acid metabolism, and insulin sensitivity. J Hepatol. 2014;60:824-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Strati F, Pujolassos M, Burrello C, Giuffrè MR, Lattanzi G, Caprioli F, Troisi J, Facciotti F. Antibiotic-associated dysbiosis affects the ability of the gut microbiota to control intestinal inflammation upon fecal microbiota transplantation in experimental colitis models. Microbiome. 2021;9:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Nakanishi Y, Sato T, Ohteki T. Commensal Gram-positive bacteria initiates colitis by inducing monocyte/macrophage mobilization. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:152-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/