Published online Jan 21, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i3.111528

Revised: September 25, 2025

Accepted: December 8, 2025

Published online: January 21, 2026

Processing time: 198 Days and 17.8 Hours

The treatment landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has significantly evolved following the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which are now the standard of care in first-line systemic therapy. However, as more patients experience progression after ICI-based combinations, the optimal second-line treatment strategy remains undefined. Currently approved agents, such as regorafenib, cabozantinib, and ramucirumab, have not been specifically tested in the post-ICI setting, and their efficacy in this context remains uncertain. This review provides a comprehensive and critical analysis of systemic second-line treatment strategies in patients with unresectable HCC after progression to frontline immunotherapy. We summarize the available evidence from early-phase studies and retrospective series and describe the rationale, efficacy signals, and development status of ongoing clinical trials. Therapeutic approaches include tyrosine kinase inhibitors, novel ICI-based combinations, bispecific antibodies, T-cell therapies (chimeric antigen receptor-T and T-cell receptor-T), and other emerging strategies such as liver-targeted prodrugs and microbiota modulation. While current data are still limited, several trials are ongoing and reflect com

Core Tip: Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma progressing after frontline immunotherapy represent an emerging clinical challenge. This review critically explores the current second-line strategies under investigation, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors, novel immune checkpoint inhibitor-based regimens, bispecific antibodies, and adoptive T-cell therapies. Most approaches are supported by strong biological rationale, although high-quality comparative data are still lacking. The multiplicity of ongoing trials underscores the need for a better understanding of resistance mechanisms and therapeutic sequencing. This review may assist clinicians and researchers in interpreting the evolving landscape and in identifying future directions for personalized, effective post-immunotherapy management.

- Citation: Ascari S, Chen R, De Sinno A, Stefanini B, Cescon M, Serenari M, Mosconi C, Tovoli F. Post-immunotherapy second-line strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma: State of the art and ongoing trials. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(3): 111528

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i3/111528.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i3.111528

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a significant global health burden, causing thousands of deaths every year. Although the widespread use of antiviral therapies has significantly reduced the incidence of virus-related HCC, a steady rise is expected in the coming years due to the global epidemic of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, affecting both high-income and low-to-middle-income countries[1].

In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-based regimens have transformed the treatment landscape for unresectable HCC. Combinations such as atezolizumab-bevacizumab, tremelimumab-durvalumab, camrelizumab-rivoceranib, and nivolumab-ipilimumab have demonstrated survival advantages over sorafenib and other multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitors (mTKIs)[2-5].

These therapeutic advances have extended median overall survival (OS) from less than one year to 18-23 months. In a relevant subset of patients, objective responses can be deep and durable[4-7], occasionally allowing downstaging and access to potentially curative treatments.

However, a substantial proportion of patients experience either primary resistance to ICIs or develop acquired resistance over time, ultimately leading to disease progression[8]. In phase III trials and global real-world studies, 40%-50% of patients who progress on first-line immunotherapy are treated with subsequent systemic therapies[4-7,9,10]. These ICI-refractory patients are a population with unmet clinical needs. All currently approved second-line agents were developed and tested in post-sorafenib settings, whereas none have been explicitly validated after first-line ICI-based combinations. Moreover, their modest objective response rates (ORR) often limit opportunities for sequential therapies with curative intent. For these reasons, international guidelines recommend referring these patients to clinical trials whenever feasible[11].

As our understanding of resistance to ICIs deepens, new therapeutic approaches are being explored to address this challenge. In recent years, numerous studies have begun investigating whether targeting specific resistance mechanisms can help improve outcomes in this population.

In this review, we provide a systematic overview of ongoing clinical trials enrolling patients with ICI-refractory HCC. Based on this analysis, we highlight emerging therapeutic approaches and identify promising directions for future drug development.

The primary objective of this review was to identify ongoing or recently completed clinical trials enrolling patients with HCC who experienced disease progression during or after immune-based combination therapies and to critically examine the emerging therapeutic strategies under investigation.

We searched two major trial registries: ClinicalTrials.gov and the European Union Clinical Trials Register. The following search terms were used under the “conditions/disease” category: HCC, hepatocellular cancer, and HCC not resectable. We included studies with the following statuses: Completed, active, not recruiting, and not yet recruiting. Trials with status “withdrawn” or clearly unrelated to therapeutic interventions were excluded. The last search was performed in March 2025.

Duplicate records across registries were identified and manually removed using trial identifier codes [national clinical trial (NCT)/EudraCT], study titles, and sponsor information. Trials were then categorized based on the mechanism of action of the investigational agents. Relevant observational studies or published data known to the authors were also incorporated to complement and contextualize the trial-based evidence.

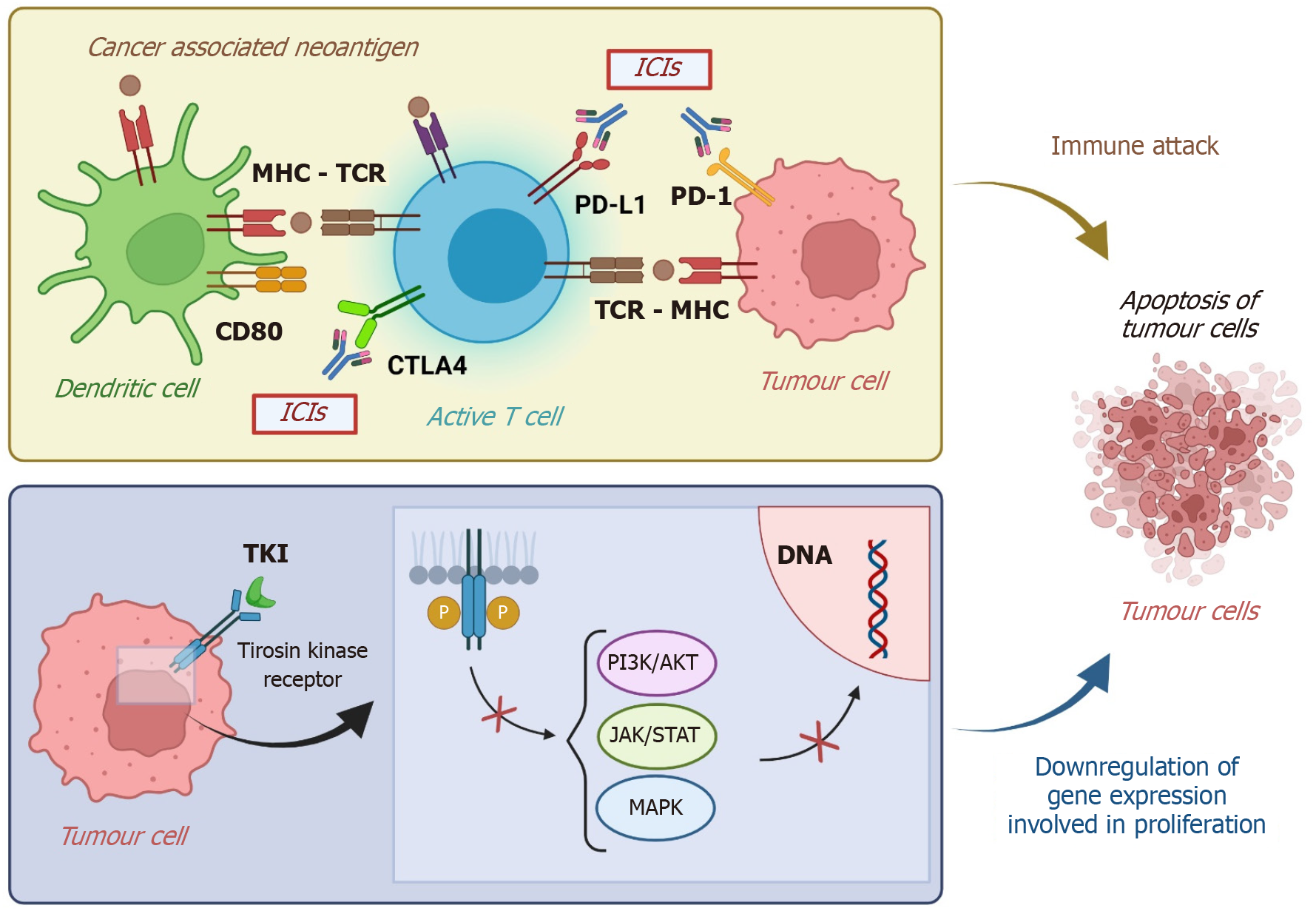

After progression on frontline ICI-based regimens, a key question is whether immune checkpoint blockade should be continued in combination with other agents. Several trials have therefore explored new partner drugs for programmed death-1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors, aiming to overcome resistance and prolong benefit. Mechanisms of resistance to first-line ICI-based therapy may be related not only to immune escape but also to tumor angiogenesis, stromal barriers, or specific oncogenic pathways. For example, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-driven angiogenesis can create an immunosuppressive microenvironment that hampers T-cell infiltration, while dense fibrotic stroma physically limits immune cell trafficking. Likewise, activation of pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin has been associated with T-cell exclusion and reduced sensitivity to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade[8]. Combining ICIs with agents that modulate these resistances mechanisms may restore or potentiate sensitivity to ICIs (Figure 1). In addition, residual ICI activity may persist beyond treatment discontinuation, allowing for synergy with sequentially introduced immunomodulatory agents. Table 1 reports ongoing clinical trials of ICI-based therapies as a second line.

| Study | Status | Description | Phase | Study design | Treatment arms | Number of patients | Population | Primary endpoint |

| NCT04770896 (imbrave 251) | Active, not recruiting | A study of atezolizumab with lenvatinib or sorafenib vs lenvatinib or sorafenib alone in hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with atezolizumab and bevacizumab | Phase 3 | RCT | Atezolizumab + lenvatinib or sorafenib; lenvatinib or Sorafenib | 554 | Progressed on atezo-bev; Child-Pugh A; PS 0-1 | OS |

| NCT05168163 | Recruiting | Atezolizumab in combination with a multi-kinase inhibitor for the treatment of unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic liver cancer | Phase 2 | RCT | Atezolizumab + cabozantinib or Lenvatinib; cabozantinib or lenvatinib | 122 | Progressed on atezo-bev; Child-Pugh A, PS 0-1 | OS, PFS |

| NCT05822752 | Active, not recruiting | Study to evaluate adverse events, and change in disease activity, when IV infused with livmoniplimab in combination with IV infused budigalimab in adult participants with HCC | Phase 2 | RCT | Lenvatinib or sorafenib; livmoniplimab dose A + budigalimab; livmoniplimab dose B + budigalimab | 130 | Progressed on ICI regimens; Child-Pugh A; PS 0-1 | BOR |

| NCT04696055 | Completed | An open-label study of regorafenib in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced or metastatic HCC After PD1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors | Phase 2 | Single-arm | Pembrolizumab + regorafenib | 95 | Progressed on ICIs regimens; Child-Pugh A, PS 0-1 | ORR |

| NCT05101629 | Active, not recruiting | Pembrolizumab and lenvatinib in patients with advanced HCC who are refractory to atezolizumab and bevacizumab/io-based therapy | Phase 2 | Single-arm | Pembrolizumab + lenvatinib | 32 | Progressed on atezo-bev; Child-Pugh A; PS 0-1 | ORR |

| NCT05199285 | Recruiting | A phase II study of nivolumab + ipilimumab in advanced HCC patients who have progressed on first line atezolizumab + bevacizumab | Phase 2 | Single-arm | Nivolumab + ipilimumab | 40 | Progressed on atezo-bev; Child-Pugh A; PS 0-1 | ORR |

| NCT05257590 | Recruiting | CVM-1118 in combination with nivolumab for unresectable advanced hepatocellular carcinoma | Phase 2 | Single-arm | Nivolumab + CVM-1118 | 31 | Progressed on atezo-bev or TKIs; child Pugh A, PS 0-1 | ORR |

| NCT05178043 | Active, not recruiting | GT90001 plus nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma | Phase 2 | Single-arm | Nivolumab + GT90001 | 5 | Progressed on ICI or ICI + TKI; Child-Pugh A; PS 0-1 | ORR |

The IMbrave251 trial (No. NCT04770896) is the first phase III, open-label, multicenter, randomized study designed to evaluate whether continuing atezolizumab in combination with either lenvatinib or sorafenib is superior to mTKI monotherapy in patients who progress after receiving atezolizumab-bevacizumab. Approximately 554 patients were randomized 1:1 to receive either atezolizumab plus a mTKI (group A) or mTKI alone (group B), with the specific mTKI (lenvatinib or sorafenib) chosen at the investigator’s discretion. The study stratified patients by mTKI type, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, disease etiology, and albumin-bilirubin score. Enrollment has been completed, and results are pending.

A separate phase 2 study (No. NCT05168163)[12], conducted across 12 United States centers is evaluating atezolizumab in combination with cabozantinib or lenvatinib vs mTKI monotherapy in patients previously treated with ICIs and anti-VEGF agents. In this trial, 122 patients will be randomized 2:1 to either atezolizumab plus mTKI or mTKI alone, with primary endpoints of progression-free survival (PFS) and OS. The trial includes biomarker analyses and longitudinal collection of tissue and blood to explore predictors of response and resistance mechanisms.

The clinical rationale for these trials lies in the hypothesis that PD-L1 inhibition may retain residual antitumor activity even after progression on atezolizumab-bevacizumab, provided that the antiangiogenic partner is changed. Should IMbrave-251 or similar studies demonstrate benefit, they would establish continuation of ICIs as a valid second-line approach, a strategy not yet proven in HCC. Nevertheless, concerns remain regarding potential cross-resistance to PD-L1 blockade, as well as the additional toxicity and cost of combining atezolizumab with mTKIs, which may limit the real-world applicability of this approach.

Pembrolizumab, an anti-PD-1 antibody, has been widely tested as a second-line option for advanced HCC. In the phase II KEYNOTE-224 trial, pembrolizumab was first shown to provide durable anti-tumor activity and a safety profile as a second-line option after progression on sorafenib, with an ORR of 18.3%[13]. However, in the subsequent phase III KEYNOTE-240 trial, pembrolizumab did not meet the predefined criteria for statistical significance in OS or PFS, despite showing numerical improvements over placebo[14]. Although the study failed to reach its co-primary endpoints, the consistency of efficacy and safety signals across both trials supported continued investigation of pembrolizumab in selected patient populations.

More recently, second-line therapy with pembrolizumab combined with mTKIs has been tested after progression on first-line regimens based on immunotherapy. The combination of pembrolizumab plus regorafenib has been evaluated in an international phase 2 study (No. NCT04696055) as a possible treatment option for patients with advanced HCC who progressed on one prior ICI regimen. This trial enrolled 95 patients, subdivided into two cohorts: Patients who had received prior atezolizumab-bevacizumab regimen (cohort 1, 68 patients) and those who had received a different prior immunotherapy approach (cohort 2, 27 patients)[15]. The most common prior ICIs in cohort 2 were durvalumab (30%), nivolumab (30%), ipilimumab (22%), and pembrolizumab (19%). The median duration of regorafenib/pembrolizumab treatment (including interruptions and delays) was shorter in cohort 1 compared to cohort 2 (11.0/9.4 weeks vs 21.4/24.1 weeks). Among patients who had experienced disease progression on atezolizumab-bevacizumab and then received the regorafenib plus pembrolizumab combination, the median PFS was 2.8 months, and the ORR was 5.9%. For the remaining 27 patients who had received a different immunotherapy in the first-line setting, the median PFS was 4.2 months, and the ORR was 11.1%. Due to the relatively short follow-up (median 7.1 months), the median OS has still to be reached in both cohorts[15].

Furthermore, pembrolizumab is under study as a possible second-line approach in combination with lenvatinib. This combination had been previously tested in a first-line setting in the LEAP-002 trial, with no statistically significant differences observed between the combination therapy and lenvatinib monotherapy[16]. However, the tails of the survival curves appeared to favor the combination arm. In the updated analysis with a 5-year follow-up, nearly twice as many patients randomized to lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab were alive at the time of database cutoff compared to those receiving lenvatinib plus placebo[17].

Currently, a trial is being conducted to analyze pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib as second-line treatment after progression on atezolizumab-bevacizumab (No. NCT05101629). In this multicenter, single-arm, open-label phase II trial, the primary objective is ORR according to response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) 1.1 criteria.

Nivolumab has been extensively tested in the multi-cohort CheckMate-040 trial. In particular, both cohort 4 and cohort 6 explored nivolumab in a post-sorafenib second-line setting, either as monotherapy or in combination with ipilimumab, an anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) agent. Results from both cohorts have been published[18,19], high

The efficacy of nivolumab-ipilimumab was also assessed after prior ICI-based combination therapies. In a multicenter retrospective study of 109 patients treated with atezolizumab and bevacizumab or other ICI-based combination therapies, 10 patients received subsequent therapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab[20]. Most of them had Barcelona clinic liver cancer stage C (80%) HCC and a preserved liver function as defined by Child-Pugh A (80%). At a median follow-up of 15.3 months, ORR for nivolumab-ipilimumab was 30%, with a disease control rate (DCR) of 40%. The median PFS was 2.9 months, and the median OS was 7.4 months[21].

This combination is also currently being studied in a multicenter, single-arm, phase II clinical trial (No. NCT05199285) aimed at investigating ORR of nivolumab-ipilimumab in patients who have progressed on atezolizumab/bevacizumab.

Nivolumab has also been analyzed in combination with GT90001 (previously known as PF-03446962), a monoclonal antibody targeting the activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK-1), a serine/threonine kinase receptor that regulates angiogenesis through interaction with the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signalling network. This combination was initially evaluated in a phase 1b/2 trial designed to determine the recommended phase 2 dose of GT90001 plus nivolumab, which showed a manageable safety profile and promising anti-tumor activity in patients with advanced HCC[22]. More recently, an open-label, multi-regional phase 2 clinical trial of GT90001 plus nivolumab has been authorized to examine the safety and efficacy of this combination in patients with advanced HCC who had progressed after first-line treatment with ICIs (No. NCT05178043). This study will enroll a total of 105 subjects to receive combinational therapy.

More recently, a phase II study has evaluated the anti-tumor effect and safety profile of CVM-1118 plus nivolumab in patients with progressive, unresectable advanced HCC following first-line therapy with mTKIs or atezolizumab-bevacizumab. CVM-1118 is a potent anti-tumor new chemical entity with multiple mechanisms of action, including the promotion of apoptosis and the delay of proliferation. Moreover, CVM-1118 targets the formation of vasculogenic mimicry, which has been associated with tumor metastasis and poor clinical outcomes[23]. Vasculogenic mimicry is reported to be particularly active in tumors under hypoxia, such as those treated with VEGF inhibitors, such as bevacizumab[23]. In this trial, 31 evaluable patients were enrolled and received oral CVM-1118 in combination with intravenous nivolumab. The duration of CVM-1118 and nivolumab treatment ranged from 1.5 months to 15.0 months (median 3.1 months), with 5/31 (16%) patients remaining on treatment for ≥ 4.6 months (range: 4.67-15.0 months). The best ORR was 19.4% (according to the modified RECIST), including two complete responses (6%), and four partial responses (13%). The remaining responses included 11 stable diseases (36%) and 14 progressive diseases (45%). The disease control rate was 54.8% [95% confidence interval (CI): 37.3%-72.3%], the median PFS was 3.53 months (95%CI: 1.9-5.4), and the median duration of response was 10.4 months (95%CI: 2.8-13.7)[24].

Livmoniplimab is a first-in-class IgG4/k monoclonal antibody that targets the glycoprotein-A repetitions predominant (GARP)-TGF-β1 complex, binding TGF-β1 to GARP and preventing the release of active TGF-β1, thereby promoting immunoreactivity[25]. This mechanism does not directly inhibit the intracellular TGF-β signalling cascade; rather, it prevents its activation at the receptor level. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that blocking TGF-β signalling can synergize with PD-1 inhibition, thereby improving tumor regression in models of immune-excluded cancers.

Recent clinical data from a phase 1 study have shown promising clinical activity for livmoniplimab and budigalimab in PD-L1 naive metastatic HCC patients, with an ORR of 42% (5/12, 4 confirmed per RECIST/5 per iRECIST)[26]. Consequently, the phase 2 LIVIGNO-2 trial was designed to continue the investigation of livmoniplimab-budigalimab in the frontline setting (No. NCT06109272). In parallel, the LIVIGNO-1 trial (No. NCT05822752) has been designed to evaluate the optimal dose of livmoniplimab and the safety and efficacy of livmoniplimab plus budigalimab in patients with locally advanced or metastatic HCC who have progressed after frontline ICI regimens for HCC. Approximately 120 subjects are planned to be enrolled in this study, divided into three cohorts (40 subjects per cohort): Cohort 1 (control arm) will be administered lenvatinib (8-12 mg, once a day) or sorafenib [800 mg (400 mg twice a day)], based on the investigator’s choice. Cohort 2 will receive livmoniplimab at dose A (400 mg IV every three weeks) plus budigalimab (375 mg IV every three weeks), while cohort 3 will be administered livmoniplimab at dose B (1200 mg IV every three weeks) plus budigalimab (375 mg IV every three weeks). The primary endpoint of this study is the best overall response as determined by the investigators according to RECIST 1.1.

Trials investigating immune-based combinations after progression on frontline immunotherapy are numerous and continue to expand. This therapeutic strategy currently represents one of the most promising approaches to enhance the efficacy of ICIs, with the potential to induce deep and durable responses. While mTKIs are being extensively evaluated as companion agents, combinations with drugs targeting alternative pathways represent underexplored but potentially valuable options. Despite the volume of ongoing research, few clinical trials have published their results to date, making cross-trial comparisons and identifying the most promising regimens challenging. Moreover, safety and tolerability represent major concerns, especially with dual immune checkpoint blockade or mTKIs, which often require careful monitoring and supportive care. With these limitations in mind, nivolumab-ipilimumab has shown the most consistent activity signals, while combinations such as pembrolizumab-regorafenib or pembrolizumab-lenvatinib have provided more modest results. Early-phase approaches, including livmoniplimab-budigalimab or anti-ALK-1 combinations, remain largely exploratory with limited clinical evidence. Overall, dual ICI blockade appears to be the most promising approach to date, whereas alternative pathway inhibitors represent underexplored but potentially valuable avenues.

To date, mTKIs represent the most readily available agents after ICI failure, given their prior approvals in the post-sorafenib setting. Although these drugs were not tested initially in the post-ICI population, they are frequently used in routine practice while awaiting prospective evidence. International guidelines recommend second-line mTKIs following progression on immunotherapy[27,28]. These recommendations are based on expert consensus rather than high-quality evidence, as all second-line clinical trials were conducted in the post-sorafenib setting, which was the standard of care at the time when those trials were initiated.

Treatment choices largely depend on local reimbursement policies and regulations. For instance, sorafenib is the only second-line treatment reimbursed in most European countries due to its previous approval for all cases of unresectable HCC[29]. On the contrary, other mTKIs are more strictly regulated. For instance, the European Medicines Agency approves lenvatinib exclusively for the first-line setting. At the same time, regorafenib and cabozantinib are approved only as post-sorafenib treatment[29].

Several studies on pharmacokinetics and cellular signalling offer insight into the rationale for using TKIs in the post-ICI setting[30,31]. Based on the prolonged effects of immunotherapy, Kudo[32] proposed that mTKIs may have a synergistic effect with previous ICIs, even when administered sequentially. This mechanism might be advantageous since mTKIs exhibit greater anti-tumor activity than bevacizumab, which targets only VEGF-A signalling and may induce the release of more cancer antigens, sustain the cancer immunity cycle, and maintain the effects of remaining anti-PD-L1 antibodies[32]. Moreover, TKIs (e.g., sorafenib, donafenib, lenvatinib, regorafenib, and cabozantinib) can improve the immune microenvironment and target tumor pathways involved in resistance to ICIs. For instance, lenvatinib inhibits FGFR4[33] and blocks the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, which is associated with primary anti-PD-L1 resistance via T-cell exclusion[34]. Regorafenib suppresses colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor and reduces tumor infiltration by tumor-associated macrophages[35]. This mechanism leads to enhanced PD-L1 inhibition and may have a role in overcoming the acquired resistance to anti-VEGF therapy.

Retrospective analyses have provided supportive signals regarding the biological activity of TKIs following immunotherapy (Table 2)[29,36-40]. In particular, lenvatinib, regorafenib, and cabozantinib have shown consistent disease control and survival outcomes across multiple cohorts of patients who progressed on atezolizumab-bevacizumab or other ICI-based regimens. These data suggest that these agents retain efficacy and may have a potential role in post-ICI treatment strategies. In contrast, the performance of sorafenib in this setting appeared less favorable, with multiple studies reporting modest response rates or shorter survival outcomes. Collectively, these findings supported the design of clinical trials exploring TKIs different from sorafenib in the post-ICI setting (Table 3).

| Treatment | Prior treatment | Ref. | Patients (number) | Region | Study design | Child Pugh-A (%) | BCLC-C (%) | MVI (%) | Extrahepatic spread (%) | mPFS (months) | mOS (months) | ORR (%) | DCR (%) | Gr3/4 TRAE (%) |

| Sora, lenva, cabo | AB | Yoo et al[37] | 49 | Asia | Retrospective | 100 | 100 | 38.8 | 6.1 (lenva); 2.5 (sora) | 16.6 (lenva); 11.2 (sora) | 15.8 (lenva); 0 (sora) | 62.1 (lenva); 63.2 (sora) | 16.3 | |

| Cabo | ICIs | Storandt et al[38] | 26 | United States | Retrospective | 72 | 2.1 | 7.7 | 4 | 27 | 27 | |||

| Rego vs other mTKIs (sora, lenva, cabo) | AB | Falette-Puisieux et al[39] | 82 | France | Retrospective | 82.9 | 92.7 | 37.8 | 80.5 | 2.6 (rego); 2.8 (other mTKIs) | 15.8 (rego); 7.0 (other mTKIs) | 17.2 (rego); 28.3 (other mTKIs) | ||

| Sora | AB | Tovoli et al[29] | 40 | Italy | Retrospective | 87.5 | 42.5 | 60 | 3.3 | 6.9 | 0 | 10 | ||

| Sora vs lenva | AB | Chon et al[40] | 126 | Korea | Retrospective | 72.2 | 86.6 | 46 | 69 | 3.5 (lenva); 1.8 (sora) | 10.3 (lenva); 7.5 (sora) | 7.5 (lenva); 5.8 (sora) | 67.5 (lenva); 24.4 (sora) | 35 (lenva); 38.4 (sora) |

| Rego | AB | Yoo et al[43] | 40 | Asia | Prospective | 100 | 97.5 | 3.5 | 9.7 | 10 | 82.5 | |||

| Cabo | ICIs | Chan et al[41] | 47 | Asia | Prospective | 100 | 93.6 | 30 | 4.3 (II line); 4.0 (III line) | 14.3 (II line); 6.6 (III line) | 6.4 | 83.1 | ||

| Lenva | AB | Yoo et al[45] | 50 | Korea | Prospective | 100 | 76 | 24 | 5.4 | 8.6 | 12 | 84 |

| Study | Status | Description | Phase | Study design | Treatment arms | Number of patients | Population | Primary endpoint |

| NCT06138769 | Active, not recruiting | Lenvatinib after progression on atezolizumab-bevacizumab in hepatocellular carcinoma | Phase 2 | Single-arm | Lenvatinib | 50 | Progressed on atezo-bev; Child-Pugh A; PS 0-1 | PFS |

| NCT04767906 (capture) | Completed | Cabozantinib treatment in a phase II study for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma refractory to PD-1 inhibitors | Phase 2 | Single-arm | Cabozantinib | 40 | Progressed on PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor; Child-Pugh A; PS 0-1; BCLC B/C | ToT |

| NCT04511455 | Completed | Cabozantinib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma refractory to first line treatment | Phase 2 | Single-arm | Cabozantinib | 22 | Progressed on lenvatinib or lenvatinib + ICIs; Child-Pugh A-B7; PS 0-1 | ToT |

| NCT0653573 (Child-Pugh AB) | Not yet recruiting | A phase 2, single arm study of cabozantinib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who have received prior atezolizumab and bevacizumab | Phase 2 | Single-arm | Cabozantinib | 40 | Progressed on atezo-bev; Child-Pugh A-B7; PS 0-1 | DCR |

| NCT06446154 | Recruiting | Fruquintinib after ICIs treatment in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma | Phase 2 | Single-arm | Fruquintinib | 36 | Progressed on ICIs; Child-Pugh A-B7; PS 0-1 | ORR |

| NCT05134532 | Unknown status | Regorafenib after progression on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma | Phase 2 | Single-arm | Regorafenib | 40 | Progressed on atezo-bev; Child-Pugh A; PS 0-1 | PFS |

| NCT04435977 | Unknown status | Efficacy and safety of cabozantinib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma | Phase 2 | Single-arm | Cabozantinib | 46 | Progressed on ICIs; Child-Pugh A; PS 0-1 | PFS |

Cabozantinib: The first prospective trial in advanced HCC patients who progressed on ICIs was an Asian multicenter phase II study on cabozantinib[41]. It enrolled 47 patients with advanced HCC who had progressed after up to two prior systemic therapies. These regimens mainly included atezolizumab-bevacizumab, anti-PD-1 monotherapy used as second-line treatment after sorafenib or lenvatinib, or ICI-based combinations administered in earlier clinical trials.

The median PFS and OS for the entire cohort were 4.1 months (95%CI: 3.3-5.3) and 9.9 months (95%CI: 7.3-14.4), respectively[41]. Among the 27 patients who received cabozantinib as second-line therapy, the median PFS and OS were 4.3 months (95%CI: 3.3-6.7) and 14.3 months (95%CI: 8.9-not reached), respectively. Outcomes were less favorable in the 20 patients treated in the third-line setting, with a median PFS of 4.0 months (95%CI: 1.4-6.6) and a median OS of 6.6 months (95%CI: 5.1-12.2)[41]. No new safety signals were reported compared with the CELESTIAL trial[42].

These results suggest that the number of prior treatment lines may influence clinical outcomes and should be considered a key stratification variable in the design of future studies on post-ICI therapies.

Regorafenib: The REGONEXT trial was a phase II study conducted in Korea that assessed regorafenib in 40 patients who had experienced disease progression following treatment with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab[43]. The median PFS was 3.5 months (95%CI: 3.0-4.0 months), and the median OS was 9.7 months (95%CI: 8.3-11.1 months). The median OS measured from the start of prior atezolizumab plus bevacizumab therapy was 16.6 months (95%CI: 11.9-21.3). The ORR was 10.0%, while the DCR reached 82.5%. These efficacy and safety outcomes were broadly consistent with those reported in the pivotal phase III RESORCE trial of regorafenib as a post-sorafenib second-line treatment[44].

Lenvatinib: No full-text reports of clinical trials of lenvatinib in the post-ICI setting have been released. However, preliminary results from a phase II study evaluating lenvatinib in 50 patients after progression on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab were presented as a communication at the European Society for Medical Oncology Asia 2024 Congress[45]. This study reported a median PFS of 5.4 months (95%CI: 5.3-5.6) and a median OS of 8.6 months (95%CI: 8.1-not assessable). Although the survival data remain immature, the ORR was 12%, and the DCR reached 84%. The incidence and profile of grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events were consistent with previous reports on lenvatinib for HCC[46].

Current data suggest that TKIs retain a degree of biological activity even after progression on ICIs. However, survival outcomes remain limited. The well-known issue of tolerability compounds this limitation, as TKIs are frequently associated with adverse events that affect treatment adherence and quality of life.

Taken together, these factors may explain the relatively low number of ongoing clinical trials investigating TKIs after ICIs. Currently, other systemic strategies are attracting greater clinical and translational interest.

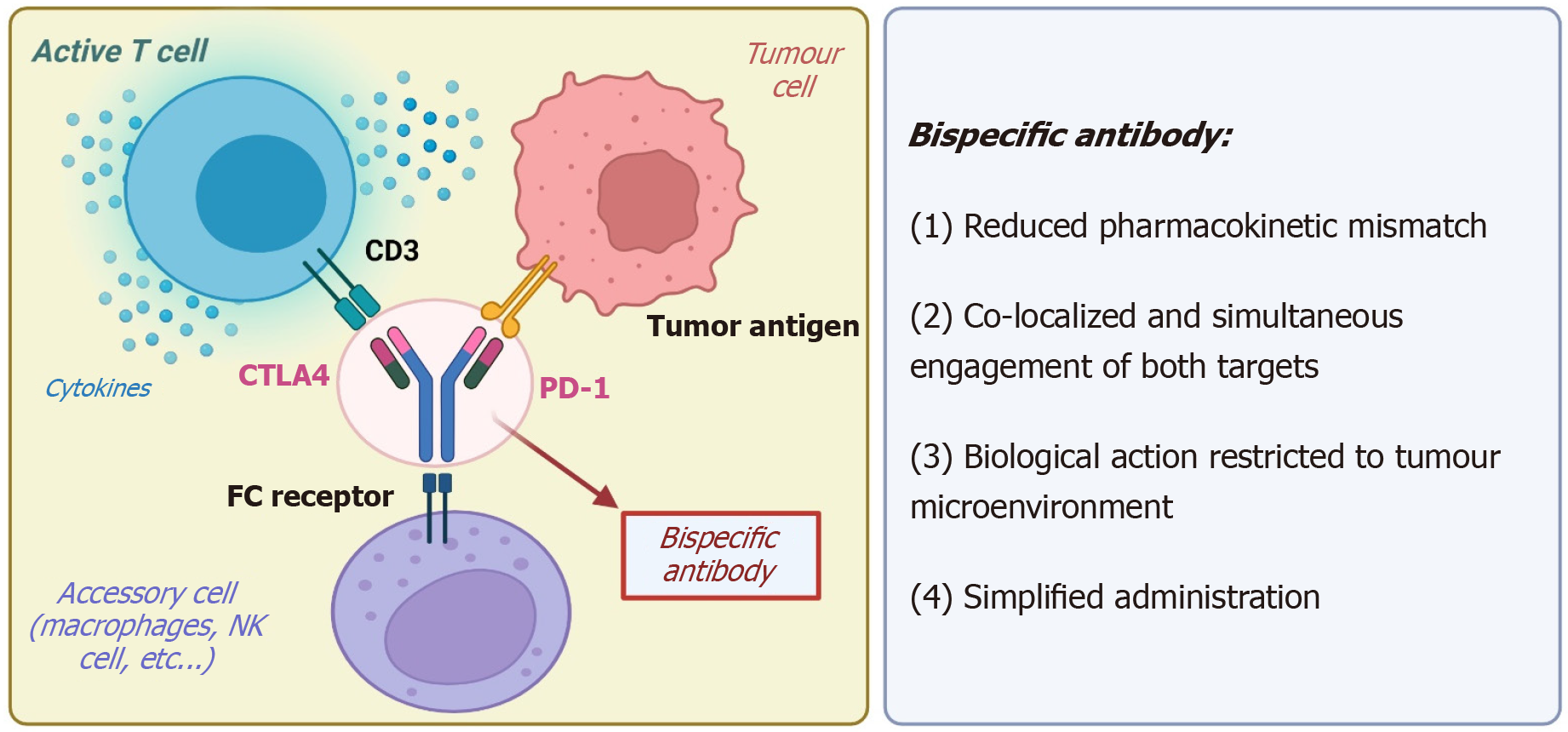

Bispecific antibodies (bsAbs) are engineered molecules designed to simultaneously bind to two different targets, enabling the complex modulation of the tumor microenvironment[47]. The most clinically advanced bsAbs in HCC target either dual immune checkpoints or immune and angiogenic pathways (Figure 2). Two different bsAbs, cadolinimab (AK104) and ivonescimab (AK112), are being tested for patients with refractory HCC.

Cadonilimab is a bsAb targeting PD-1 and CTLA-4. The therapeutic rationale behind this agent is based on the hypothesis that dual checkpoint blockade, delivered through a single molecule, may enhance anti-tumor immune responses while reducing the toxicity typically observed with the concurrent administration of two monoclonal antibodies. Several phase II trials are currently evaluating cadonilimab in combination with either the VEGF inhibitor bevacizumab (No. NCT05760599) or TKIs such as regorafenib and lenvatinib.

Ivonescimab is a bsAb that targets both PD-1 and VEGF-A, aiming to harness the synergistic effects of immune check

Ivonescimab is being investigated as monotherapy or in combination with the anti-TIGIT antibody AK130 in a phase Ib trial (No. NCT06530251), enrolling patients who have progressed after one or two prior systemic therapies. Intriguingly, another study is evaluating the combination of ivonescimab and cadonilimab as a dual bsAb strategy. The target population is represented by patients who experienced disease progression or intolerance following a prior ICI plus antiangiogenic regimen.

Collectively, these trials reflect a still-limited but growing interest in bsAbs for the treatment of HCC. Currently, they are being investigated in early-phase studies, which often lack active comparators. Larger, randomized trials will be necessary to clarify their efficacy, safety, and potential positioning within the post-ICI landscape.

Adoptive T-cell therapies include chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells and T-cell receptor (TCR)-engineered T-cells. These therapies are being evaluated as innovative immunotherapeutic strategies in HCC. Although these approaches remain largely investigational, most clinical studies to date have enrolled patients who were previously exposed to systemic therapy, including ICIs, making them relevant in the second-line setting.

CAR T-cell therapy involves the collection and ex vivo genetic engineering of autologous T lymphocytes to express synthetic receptors capable of recognizing tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) on the surface of malignant cells. CAR T-cell therapy has achieved regulatory approval in haematological malignancies, prompting interest in its applicability to solid tumors, such as HCC[48].

TCR-engineered T-cell therapy is a distinct modality of adoptive immunotherapy in which autologous T-cells are genetically modified to express high-affinity TCRs specific for intracellular TAAs presented via major histocompatibility complex molecules[49]. Unlike CARs, which recognize extracellular targets in a human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-independent manner, TCR T-cells can detect lower-abundance antigens that are processed and displayed on the tumor cell surface, thereby expanding the range of possible targets[50]. However, this approach is restricted to patients with specific HLA haplotypes[51] and requires complex engineering.

Several TAAs have shown promise as CAR targets in HCC in preclinical studies, including glypican-3 (GPC-3), AFP, cluster of differentiation (CD) 133, CD147, epithelial cell adhesion molecule, cellular-mesenchymal epithelial transition factor, and MUC1. Among these, CD133-directed CAR T-cells have reached early-phase clinical evaluation. In a phase I/II, single-arm, open-label study (No. NCT02541370), 21 patients with advanced HCC received autologous CD133-targeted CAR T cells following at least one prior systemic therapy most commonly sorafenib[52]. The administered dose ranged from 0.5 × 106 to 2 × 106 cells/kg, with additional cycles permitted in the absence of progression or toxicity. Despite poor baseline characteristics (57.1% Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 2; 57.1% Child-Pugh B), one patient achieved a partial response, and 14 (66.7%) had stable disease at first imaging. Median PFS and OS were 6.8 and 12.0 months, respectively. These data were notable, given the unfavorable clinical profile of the cohort[53].

Additionally, a GPC-3-targeted CAR T-cell therapy (No. NCT05003895) is currently being investigated in a phase I/II study. The ongoing trial is evaluating safety, expansion kinetics, and early signs of anti-tumor activity in patients with advanced HCC, including those previously treated with ICIs. Although mature results are not yet available, targeting GPC-3 remains among the most promising avenues within adoptive cell therapy for HCC.

TCR-engineered T-cells targeting AFP have also shown preliminary activity. At the International Liver Cancer Association 2021, data from a phase I trial of ADP-A2AFP specific peptide enhanced affinity receptor T-cells (No. NCT03132792) were presented. Eligible patients had histologically confirmed HCC, tumor AFP expression, and HLA-A 02:01 and had either progressed on or declined standard systemic therapy. Among the first 13 patients treated, one had a complete response, six had stable disease, and four progressed. Two patients had not yet reached the first imaging at the time of data cutoff. Adverse events were manageable and consistent with other cell therapies. Higher doses of infused T-cells (> 1 billion) were associated with greater reductions in serum AFP levels, which in turn correlated with clinical benefit[53].

Adoptive T-cell therapies represent an innovative and technologically advanced approach to immunotherapy. Despite encouraging signals in HCC, several obstacles limit their widespread use, including the need for complex manufacturing infrastructure, high cost, and HLA restriction (in the case of TCR therapies). Both CAR-T and TCR-T approaches also carry significant safety risks, including cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity. Moreover, the prerequisite of lymphodepleting chemotherapy raises additional concerns regarding hepatotoxicity in patients with underlying liver disease. In the near future, new early-phase studies of adoptive T-cell therapies are expected, but their clinical applicability remains unknown.

Most studies of second-line treatments for patients with HCC refractory to ICIs follow established research directions, such as immunotherapy-based approaches and TKIs. However, a subset of trials is exploring entirely novel strategies, including conventional chemotherapy prodrugs designed to minimize systemic toxicity and microbiota-based interventions aimed at enhancing anti-tumor immune responses.

Fostroxacitabine is a liver-targeted oral prodrug of troxacitabine, a nucleoside analogue whose anti-tumor activity is mediated by inhibition of DNA replication. The drug is rapidly absorbed and selectively metabolized in hepatocytes, enhancing tumor specificity while limiting systemic toxicity.

Foxtrocitabine bralpamide (fostrox, MIV-818) is currently under investigation as a potential therapeutic option for HCC in a phase 1b/2 clinical trial. The phase 1b portion was designed to determine the maximum tolerated dose and included patients with HCC, other primary liver tumors, and metastatic liver disease. Fostrox was administered in combination with either lenvatinib or pembrolizumab. In the phase 1b cohort, the median patient age was 62 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 3:1. Viral aetiology accounted for 76% of cases, and 67% of patients had extrahepatic disease. A substantial proportion (70%) had received prior locoregional therapies, and 86% had previously been treated with atezolizumab and bevacizumab. The fostrox-lenvatinib combination was well tolerated, with no unexpected adverse events reported. Hematologic adverse events were the most frequent, including grade ≥ 3 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia in 11 patients; four patients experienced grade 4 events[54]. Initial efficacy analyses showed an ORR of 24% and a time to progression of 10.9 months[54]. These results prompted the initiation of the phase 2 portion of the study, which is now open for recruitment. The trial will include three arms in a 1:1:1 ratio: Fostrox 30 mg plus lenvatinib, fostrox 10 mg plus lenvatinib, and a control arm with lenvatinib plus placebo. Unlike the phase 1b cohort, the phase 2b study will exclusively enroll patients with HCC who have progressed on first-line ICI-based therapy (No. NCT03781934).

Gut microbiota is often altered in liver cirrhosis and HCC, and increasing evidence suggests that it may influence response to immunotherapy[55]. Consequently, strategies to modulate the gut microbiome, such as faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), may help to improve the efficacy of ICIs or even overcome resistance to immunotherapy. Two phase 1 studies for patients with melanoma confirmed the feasibility and efficacy of FMT from donors who achieved tumor response with ICIs in patients with tumor progression under ICIs[56,57].

FAB-HCC (No. NCT05750030) is a single-center, single-arm, phase II pilot study designed to evaluate the safety, feasibility, and efficacy of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in combination with FMT from anti-PD-L1 responder or healthy donors to adult patients with HCC who failed to achieve or maintain a complete or partial radiological response to atezolizumab plus bevacizumab[58]. This study plans to enroll 12 patients. Results from an interim analysis conducted after the enrollment of the first six patients were presented at the 2024 European Association for the Study of the Liver International Liver Congress[59]. Patients were predominantly males (n = 5) with underlying viral liver disease (n = 4). They were included in the study following progression (n = 2) or stable disease (n = 4) under treatment with atezolizumab-bevacizumab. FMT was well tolerated, with minor adverse events, including bloating (G1, n = 2), constipation (G2, n = 2), and diarrhoea (G1, n = 1). Atezolizumab-bevacizumab was restarted after the FMT, obtaining a partial response in two patients[59].

The multitude of emerging therapeutic strategies for HCC reflects the ongoing need for innovative solutions in this challenging-to-treat condition. These approaches are still in very early stages of development, making it difficult to predict their efficacy, safety, and clinical applicability at this time.

Despite the growing clinical relevance of patients progressing after ICI-based regimens, evidence supporting second-line systemic options remains limited. Available data primarily derive from early-phase studies or retrospective analyses, with no randomized trial yet establishing a new standard of care in this setting. Several second-line strategies are under active investigation, encompassing ICI-based combinations, mTKIs, bsAbs, adoptive T-cell therapies, and non-conventional approaches such as microbiota modulation. This fragmentation should not be viewed negatively: The parallel exploration of diverse approaches may accelerate the understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying HCC progression and immune resistance, while also increasing the likelihood of identifying effective regimens within a shorter timeframe.

Beyond efficacy signals, the clinical development of second-line strategies must address the substantial issue of safety and quality of life. For instance, mTKIs are consistently associated with adverse events that may lead to dose reductions or discontinuations, and these events can have a significant impact on quality of life. Dual immune checkpoint blockade, while capable of inducing deep responses, carries a high risk of immune-related adverse events, including hepatitis, colitis, and endocrinopathies, which are particularly challenging in patients with underlying cirrhosis. Likewise, adoptive T-cell therapies such as CAR-T and TCR-T approaches are associated with potentially life-threatening complications, including cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity, and require intensive monitoring in specialized centers. In patients living with HCC, where comorbidities and liver dysfunction are common, these safety issues can become limiting factors for real-world applicability. A balanced evaluation of risk–benefit ratios is therefore essential to translate efficacy into tangible clinical benefit.

Even when novel agents demonstrate clinical activity, their real-world impact will largely depend on accessibility and sustainability within healthcare systems. Many of the investigational strategies are associated with high costs and logistical challenges. Disparities in drug approval and reimbursement policies already influence the availability of second-line options across regions, with TKIs such as cabozantinib and regorafenib not uniformly reimbursed outside of their original post-sorafenib indications. In resource-limited settings, economic barriers may outweigh clinical evidence, thereby restricting patient access to potentially beneficial therapies.

Another key unmet need is the identification of reliable biomarkers. Mechanisms of resistance vary depending on the first-line regimen for example, angiogenic escape after atezolizumab-bevacizumab vs T-cell exclusion pathways after CTLA-4/PD-L1 combinations. Stratifying patients according to these resistance mechanisms will be crucial for rationalizing therapeutic sequencing. Current research efforts are increasingly exploring genomic, transcriptomic, and immunologic correlations of response, as well as circulating biomarkers and radiomic signatures. The integration of such tools may enable precision-based treatment allocation, reducing unnecessary toxicity and cost while maximizing the likelihood of benefit. In parallel, incorporating patient-reported outcomes and quality-of-life assessments into trial design will help capture dimensions of benefit that extend beyond radiological response. Taken together, these approaches may transform the current empiric sequencing of systemic therapies into a more individualized and biologically informed strategy.

No second-line agent or combination has yet been approved for patients progressing after these regimens, despite the growing frequency of this clinical scenario in real-world practice. Currently, a wide range of investigational strategies is under active evaluation, encompassing immunotherapeutic combinations, mTKIs, bsAbs, adoptive T-cell therapies, and unconventional approaches such as microbiota modulation. This heterogeneity reflects the absence of a unifying treatment standard and highlights the need for continued research aimed at overcoming immune resistance. Identifying active, tolerable, and accessible second-line options after ICI-based combinations will likely require both innovative agents and a refined understanding of HCC biology. Future innovation will require not only randomized evidence but also integration of biomarkers, patient-centered outcomes, and real-world considerations to ensure that emerging therapies translate into tangible benefits for patients with HCC.

| 1. | Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, Lesi O, Cabasag CJ, Vignat J, Laversanne M, McGlynn KA, Soerjomataram I. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1598-1606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 1417] [Article Influence: 354.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Li D, Verret W, Xu DZ, Hernandez S, Liu J, Huang C, Mulla S, Wang Y, Lim HY, Zhu AX, Cheng AL; IMbrave150 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894-1905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2542] [Cited by in RCA: 5324] [Article Influence: 887.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (29)] |

| 3. | Abou-Alfa GK, Lau G, Kudo M, Chan SL, Kelley RK, Furuse J, Sukeepaisarnjaroen W, Kang YK, Van Dao T, De Toni EN, Rimassa L, Breder V, Vasilyev A, Heurgué A, Tam VC, Mody K, Thungappa SC, Ostapenko Y, Yau T, Azevedo S, Varela M, Cheng AL, Qin S, Galle PR, Ali S, Marcovitz M, Makowsky M, He P, Kurland JF, Negro A, Sangro B. Tremelimumab plus Durvalumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. NEJM Evid. 2022;1:EVIDoa2100070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 992] [Cited by in RCA: 866] [Article Influence: 216.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Qin S, Chan SL, Gu S, Bai Y, Ren Z, Lin X, Chen Z, Jia W, Jin Y, Guo Y, Hu X, Meng Z, Liang J, Cheng Y, Xiong J, Ren H, Yang F, Li W, Chen Y, Zeng Y, Sultanbaev A, Pazgan-Simon M, Pisetska M, Melisi D, Ponomarenko D, Osypchuk Y, Sinielnikov I, Yang TS, Liang X, Chen C, Wang L, Cheng AL, Kaseb A, Vogel A; CARES-310 Study Group. Camrelizumab plus rivoceranib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (CARES-310): a randomised, open-label, international phase 3 study. Lancet. 2023;402:1133-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 158.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Yau T, Galle PR, Decaens T, Sangro B, Qin S, da Fonseca LG, Karachiwala H, Blanc JF, Park JW, Gane E, Pinter M, Peña AM, Ikeda M, Tai D, Santoro A, Pizarro G, Chiu CF, Schenker M, He A, Chon HJ, Wojcik-Tomaszewska J, Verset G, Wang QQ, Stromko C, Neely J, Singh P, Jimenez Exposito MJ, Kudo M; CheckMate 9DW investigators. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus lenvatinib or sorafenib as first-line treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 9DW): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2025;405:1851-1864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 113.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rimassa L, Chan SL, Sangro B, Lau G, Kudo M, Reig M, Breder V, Ryu MH, Ostapenko Y, Sukeepaisarnjaroen W, Varela M, Tougeron D, Crysler OV, Bouattour M, Van Dao T, Tam VC, Faccio A, Furuse J, Jeng LB, Kang YK, Kelley RK, Paskow MJ, Ran D, Xynos I, Kurland JF, Negro A, Abou-Alfa GK. Five-year overall survival update from the HIMALAYA study of tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable HCC. J Hepatol. 2025;83:899-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 52.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, Lim HY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Li D, Verret W, Ma N, Nicholas A, Wang Y, Li L, Zhu AX, Finn RS. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76:862-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 1180] [Article Influence: 295.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pinyol R, Sia D, Llovet JM. Immune Exclusion-Wnt/CTNNB1 Class Predicts Resistance to Immunotherapies in HCC. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:2021-2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chan LL, Kwong TT, Yau JCW, Chan SL. Treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma after immunotherapy. Ann Hepatol. 2025;30:101781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stefanini B, Piscaglia F, Marra F, Iavarone M, Vivaldi C, Cabibbo G, Palloni A, Pressiani T, Dalbeni A, Stefanini B, Stella L, Federico P, Svegliati-Baroni G, Lonardi S, Soldà C, Ielasi L, De Lorenzo S, Garajova I, Campani C, Bruccoleri M, Masi G, Celsa C, Brandi G, Auriemma A, Daniele B, Ponziani FR, Lani L, Chen R, Boe M, Granito A, Rimassa L, Tovoli F; ARTE study group. Etiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma May Influence the Pattern of Progression under Atezolizumab-Bevacizumab. Liver Cancer. 2025;1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2025;82:315-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 347.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 12. | Ma WW, Ou F, Li JJ, Tran NH, Babiker HM, Revzin A, Dong H, Nelson GD, Ness A, Schuster CE, Jia J, Bekaii-Saab TS, Academic and Community Cancer Research United (ACCRU). ACCRU-GI-2008: A phase II randomized study of atezolizumab (Atezo) plus a multi-kinase inhibitor (MKI) versus MKI alone in patients with unresectable advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) who previously received atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (Bev). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:TPS4170. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kudo M, Finn RS, Edeline J, Cattan S, Ogasawara S, Palmer DH, Verslype C, Zagonel V, Fartoux L, Vogel A, Sarker D, Verset G, Chan SL, Knox J, Daniele B, Yau T, Gurary EB, Siegel AB, Wang A, Cheng AL, Zhu AX; KEYNOTE-224 Investigators. Updated efficacy and safety of KEYNOTE-224: a phase II study of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib. Eur J Cancer. 2022;167:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Finn RS, Ryoo BY, Merle P, Kudo M, Bouattour M, Lim HY, Breder V, Edeline J, Chao Y, Ogasawara S, Yau T, Garrido M, Chan SL, Knox J, Daniele B, Ebbinghaus SW, Chen E, Siegel AB, Zhu AX, Cheng AL; KEYNOTE-240 investigators. Pembrolizumab As Second-Line Therapy in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:193-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1365] [Cited by in RCA: 1399] [Article Influence: 233.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | El-Khoueiry AB, Kim T, Blanc J, Rosmorduc O, Decaens T, Mathurin P, Merle P, Dayyani F, Masi G, Pressiani T, Galle PR, Hatogai K, Ishii Y, Seidel H, Mueller U, Kalambakas SA, Bouattour M. International, open-label phase 2 study of regorafenib plus pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) previously treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI). J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:4007. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Llovet JM, Kudo M, Merle P, Meyer T, Qin S, Ikeda M, Xu R, Edeline J, Ryoo BY, Ren Z, Masi G, Kwiatkowski M, Lim HY, Kim JH, Breder V, Kumada H, Cheng AL, Galle PR, Kaneko S, Wang A, Mody K, Dutcus C, Dubrovsky L, Siegel AB, Finn RS; LEAP-002 Investigators. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus lenvatinib plus placebo for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (LEAP-002): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:1399-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 97.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Finn RS, Kudo M, Merle P, Meyer T, Qin S, Ikeda M, Xu R, Edeline J, Ryoo B, Ren Z, Cheng A, Galle PR, Kaneko S, Kumada H, Pollack S, Mody K, Dubrovsky L, Adelberg DE, Llovet J. LEAP-002 long-term follow-up: Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus lenvatinib plus placebo for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:4095. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Yau T, Zagonel V, Santoro A, Acosta-Rivera M, Choo SP, Matilla A, He AR, Cubillo Gracian A, El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Eldawy TE, Bruix J, Frassineti GL, Vaccaro GM, Tschaika M, Scheffold C, Koopmans P, Neely J, Piscaglia F. Nivolumab Plus Cabozantinib With or Without Ipilimumab for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Results From Cohort 6 of the CheckMate 040 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:1747-1757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Melero I, Yau T, Kang YK, Kim TY, Santoro A, Sangro B, Kudo M, Hou MM, Matilla A, Tovoli F, Knox J, He AR, El-Rayes B, Acosta-Rivera M, Lim HY, Soleymani S, Yao J, Neely J, Tschaika M, Hsu C, El-Khoueiry AB. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib: 5-year results from CheckMate 040. Ann Oncol. 2024;35:537-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Roessler D, Öcal O, Philipp AB, Markwardt D, Munker S, Mayerle J, Jochheim LS, Hammer K, Lange CM, Geier A, Seidensticker M, Reiter FP, De Toni EN, Ben Khaled N. Ipilimumab and nivolumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma after failure of prior immune checkpoint inhibitor-based combination therapies: a multicenter retrospective study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:3065-3073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hu-Lowe DD, Chen E, Zhang L, Watson KD, Mancuso P, Lappin P, Wickman G, Chen JH, Wang J, Jiang X, Amundson K, Simon R, Erbersdobler A, Bergqvist S, Feng Z, Swanson TA, Simmons BH, Lippincott J, Casperson GF, Levin WJ, Stampino CG, Shalinsky DR, Ferrara KW, Fiedler W, Bertolini F. Targeting activin receptor-like kinase 1 inhibits angiogenesis and tumorigenesis through a mechanism of action complementary to anti-VEGF therapies. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1362-1373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hsu C, Chang YF, Yen CJ, Xu YW, Dong M, Tong YZ. Combination of GT90001 and nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter, single-arm, phase 1b/2 study. BMC Med. 2023;21:395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shen L, Chen YL, Huang CC, Shyu YC, Seftor REB, Seftor EA, Hendrix MJC, Chien DS, Chu YW. CVM-1118 (foslinanib), a 2-phenyl-4-quinolone derivative, promotes apoptosis and inhibits vasculogenic mimicry via targeting TRAP1. Pathol Oncol Res. 2023;29:1611038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yen C, Huang Y, Yeh K, Chen P, Lu S, Gutheil J, Melink TJ, Chen Y, Chen C, Chao T, Chu Y, Chien D. CVM-1118: A potent oral anti-vasculogenic mimicry (VM) agent in combination with nivolumab in patients with unresectable advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)—A phase IIa study. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:e16150. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | de Streel G, Bertrand C, Chalon N, Liénart S, Bricard O, Lecomte S, Devreux J, Gaignage M, De Boeck G, Mariën L, Van De Walle I, van der Woning B, Saunders M, de Haard H, Vermeersch E, Maes W, Deckmyn H, Coulie PG, van Baren N, Lucas S. Selective inhibition of TGF-β1 produced by GARP-expressing Tregs overcomes resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in cancer. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shimizu T, Powderly J, Abdul Razak A, LoRusso P, Miller KD, Kao S, Kongpachith S, Tribouley C, Graham M, Stoll B, Patel M, Sahtout M, Blaney M, Leibman R, Golan T, Tolcher A. First-in-human phase 1 dose-escalation results with livmoniplimab, an antibody targeting the GARP:TGF-ß1 complex, as monotherapy and in combination with the anti-PD-1 antibody budigalimab in patients with advanced solid tumors. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1376551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Singal AG, Llovet JM, Yarchoan M, Mehta N, Heimbach JK, Dawson LA, Jou JH, Kulik LM, Agopian VG, Marrero JA, Mendiratta-Lala M, Brown DB, Rilling WS, Goyal L, Wei AC, Taddei TH. AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2023;78:1922-1965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 900] [Cited by in RCA: 1168] [Article Influence: 389.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (23)] |

| 28. | Ducreux M, Abou-Alfa GK, Bekaii-Saab T, Berlin J, Cervantes A, de Baere T, Eng C, Galle P, Gill S, Gruenberger T, Haustermans K, Lamarca A, Laurent-Puig P, Llovet JM, Lordick F, Macarulla T, Mukherji D, Muro K, Obermannova R, O'Connor JM, O'Reilly EM, Osterlund P, Philip P, Prager G, Ruiz-Garcia E, Sangro B, Seufferlein T, Tabernero J, Verslype C, Wasan H, Van Cutsem E. The management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Current expert opinion and recommendations derived from the 24th ESMO/World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer, Barcelona, 2022. ESMO Open. 2023;8:101567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tovoli F, Pallotta DP, Vivaldi C, Campani C, Federico P, Palloni A, Dalbeni A, Soldà C, Lani L, Svegliati-Baroni G, Garajova I, Ielasi L, De Lorenzo S, Granito A, Stefanini B, Masi G, Marra F, Lonardi S, Brandi G, Daniele B, Auriemma A, Schiadà L, Chen R, Piscaglia F; ARTE study group. Suboptimal outcomes of sorafenib as a second-line treatment after atezolizumab-bevacizumab for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2024;56:2079-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wu M, Fulgenzi CAM, D'Alessio A, Cortellini A, Celsa C, Manfredi GF, Stefanini B, Wu YL, Huang YH, Saeed A, Pirozzi A, Pressiani T, Rimassa L, Schoenlein M, Schulze K, von Felden J, Mohamed Y, Kaseb AO, Vogel A, Roehlen N, Silletta M, Nishida N, Kudo M, Vivaldi C, Balcar L, Scheiner B, Pinter M, Singal AG, Glover J, Ulahannan S, Foerster F, Weinmann A, Galle PR, Parikh ND, Hsu WF, Parisi A, Chon HJ, Pinato DJ, Ang C. Second-line treatment patterns and outcomes in advanced HCC after progression on atezolizumab/bevacizumab. JHEP Rep. 2025;7:101232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Osa A, Uenami T, Koyama S, Fujimoto K, Okuzaki D, Takimoto T, Hirata H, Yano Y, Yokota S, Kinehara Y, Naito Y, Otsuka T, Kanazu M, Kuroyama M, Hamaguchi M, Koba T, Futami Y, Ishijima M, Suga Y, Akazawa Y, Machiyama H, Iwahori K, Takamatsu H, Nagatomo I, Takeda Y, Kida H, Akbay EA, Hammerman PS, Wong KK, Dranoff G, Mori M, Kijima T, Kumanogoh A. Clinical implications of monitoring nivolumab immunokinetics in non-small cell lung cancer patients. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e59125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kudo M. Sequential Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Failure of Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab Combination Therapy. Liver Cancer. 2021;10:85-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tohyama O, Matsui J, Kodama K, Hata-Sugi N, Kimura T, Okamoto K, Minoshima Y, Iwata M, Funahashi Y. Antitumor activity of lenvatinib (e7080): an angiogenesis inhibitor that targets multiple receptor tyrosine kinases in preclinical human thyroid cancer models. J Thyroid Res. 2014;2014:638747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ruiz de Galarreta M, Bresnahan E, Molina-Sánchez P, Lindblad KE, Maier B, Sia D, Puigvehi M, Miguela V, Casanova-Acebes M, Dhainaut M, Villacorta-Martin C, Singhi AD, Moghe A, von Felden J, Tal Grinspan L, Wang S, Kamphorst AO, Monga SP, Brown BD, Villanueva A, Llovet JM, Merad M, Lujambio A. β-Catenin Activation Promotes Immune Escape and Resistance to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:1124-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 686] [Article Influence: 98.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zopf D, Fichtner I, Bhargava A, Steinke W, Thierauch KH, Diefenbach K, Wilhelm S, Hafner FT, Gerisch M. Pharmacologic activity and pharmacokinetics of metabolites of regorafenib in preclinical models. Cancer Med. 2016;5:3176-3185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhu Y, Yang J, Xu D, Gao XM, Zhang Z, Hsu JL, Li CW, Lim SO, Sheng YY, Zhang Y, Li JH, Luo Q, Zheng Y, Zhao Y, Lu L, Jia HL, Hung MC, Dong QZ, Qin LX. Disruption of tumour-associated macrophage trafficking by the osteopontin-induced colony-stimulating factor-1 signalling sensitises hepatocellular carcinoma to anti-PD-L1 blockade. Gut. 2019;68:1653-1666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yoo C, Kim JH, Ryu MH, Park SR, Lee D, Kim KM, Shim JH, Lim YS, Lee HC, Lee J, Tai D, Chan SL, Ryoo BY. Clinical Outcomes with Multikinase Inhibitors after Progression on First-Line Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Multinational Multicenter Retrospective Study. Liver Cancer. 2021;10:107-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Storandt MH, Gile JJ, Palmer ME, Zemla TJ, Ahn DH, Bekaii-Saab TS, Jin Z, Tran NH, Mahipal A. Cabozantinib Following Immunotherapy in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:5173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Falette-Puisieux M, Nault JC, Bouattour M, Lequoy M, Amaddeo G, Decaens T, Di Fiore F, Manfredi S, Merle P, Baron A, Locher C, Pellat A, Coriat R. Beyond atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: overall efficacy and safety of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in a real-world setting. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2023;15:17588359231189425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Chon YE, Kim DY, Kim MN, Kim BK, Kim SU, Park JY, Ahn SH, Ha Y, Lee JH, Lee KS, Kang B, Kim JS, Chon HJ, Kim DY. Sorafenib vs. Lenvatinib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma after atezolizumab/bevacizumab failure: A real-world study. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2024;30:345-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chan SL, Ryoo BY, Mo F, Chan LL, Cheon J, Li L, Wong KH, Yim N, Kim H, Yoo C. Multicentre phase II trial of cabozantinib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment. J Hepatol. 2024;81:258-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, El-Khoueiry AB, Rimassa L, Ryoo BY, Cicin I, Merle P, Chen Y, Park JW, Blanc JF, Bolondi L, Klümpen HJ, Chan SL, Zagonel V, Pressiani T, Ryu MH, Venook AP, Hessel C, Borgman-Hagey AE, Schwab G, Kelley RK. Cabozantinib in Patients with Advanced and Progressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:54-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1630] [Cited by in RCA: 1862] [Article Influence: 232.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 43. | Yoo C, Cheon J, Ryoo B, Ryu M, Kim H, Kim K, Kang B, Chon HJ, Finn RS. Second-line regorafenib in patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) after progression on first-line atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (Atezo-Bev): Phase 2 REGONEXT trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:477. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 44. | Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, Pracht M, Yokosuka O, Rosmorduc O, Breder V, Gerolami R, Masi G, Ross PJ, Song T, Bronowicki JP, Ollivier-Hourmand I, Kudo M, Cheng AL, Llovet JM, Finn RS, LeBerre MA, Baumhauer A, Meinhardt G, Han G; RESORCE Investigators. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2160] [Cited by in RCA: 2843] [Article Influence: 315.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 45. | Yoo C, Kim H, Chon H, Sym S, Kim M, Kang J, Ryoo B, Lee C, Hong J, Ryu H, Bae W, Kim H, Kim H, Kim J, Kim T. LBA1 Multicenter phase II trial of lenvatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma after progression on first-line atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (KCSG HB23-04). Ann Oncol. 2024;35:S1450. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 46. | Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, Baron A, Park JW, Han G, Jassem J, Blanc JF, Vogel A, Komov D, Evans TRJ, Lopez C, Dutcus C, Guo M, Saito K, Kraljevic S, Tamai T, Ren M, Cheng AL. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163-1173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4432] [Cited by in RCA: 4115] [Article Influence: 514.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 47. | FDA. Research C for DE and Bispecific Antibodies: An Area of Research and Clinical Applications. [cited December 04, 2025]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/. |

| 48. | Feins S, Kong W, Williams EF, Milone MC, Fraietta JA. An introduction to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:S3-S9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 56.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Roddy H, Meyer T, Roddie C. Novel Cellular Therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Huang J, Brameshuber M, Zeng X, Xie J, Li QJ, Chien YH, Valitutti S, Davis MM. A single peptide-major histocompatibility complex ligand triggers digital cytokine secretion in CD4(+) T cells. Immunity. 2013;39:846-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | González-Galarza FF, Takeshita LY, Santos EJ, Kempson F, Maia MH, da Silva AL, Teles e Silva AL, Ghattaoraya GS, Alfirevic A, Jones AR, Middleton D. Allele frequency net 2015 update: new features for HLA epitopes, KIR and disease and HLA adverse drug reaction associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D784-D788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 594] [Cited by in RCA: 632] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Dai H, Tong C, Shi D, Chen M, Guo Y, Chen D, Han X, Wang H, Wang Y, Shen P. Efficacy and biomarker analysis of CD133-directed CAR T cells in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a single-arm, open-label, phase II trial. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9:1846926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | OncLive. ADP-A2AFP SPEAR T Cells Demonstrate Efficacy, Tolerability in Advanced HCC. [cited December 04, 2025]. Available from: https://www.onclive.com/view/adp-a2afp-spear-t-cells-demonstrate-efficacy-tolerability-in-advanced-hcc. |

| 54. | Plummer R, Greystoke A, Naylor G, Sarker D, Anam ANMK, Prenen H, Teuwen LA, Van Cutsem E, Dekervel J, Haugk B, Ness T, Bhoi S, Jensen M, Morris T, Baumann P, Sjögren N, Tunblad K, Wallberg H, Öberg F, Evans TRJ. A Phase 1a/1b Study of Fostroxacitabine Bralpamide (Fostrox) Monotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Solid Tumor Liver Metastases. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2024;11:2033-2047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Schwabe RF, Greten TF. Gut microbiome in HCC - Mechanisms, diagnosis and therapy. J Hepatol. 2020;72:230-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 45.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Baruch EN, Youngster I, Ben-Betzalel G, Ortenberg R, Lahat A, Katz L, Adler K, Dick-Necula D, Raskin S, Bloch N, Rotin D, Anafi L, Avivi C, Melnichenko J, Steinberg-Silman Y, Mamtani R, Harati H, Asher N, Shapira-Frommer R, Brosh-Nissimov T, Eshet Y, Ben-Simon S, Ziv O, Khan MAW, Amit M, Ajami NJ, Barshack I, Schachter J, Wargo JA, Koren O, Markel G, Boursi B. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science. 2021;371:602-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in RCA: 1154] [Article Influence: 192.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Davar D, Dzutsev AK, McCulloch JA, Rodrigues RR, Chauvin JM, Morrison RM, Deblasio RN, Menna C, Ding Q, Pagliano O, Zidi B, Zhang S, Badger JH, Vetizou M, Cole AM, Fernandes MR, Prescott S, Costa RGF, Balaji AK, Morgun A, Vujkovic-Cvijin I, Wang H, Borhani AA, Schwartz MB, Dubner HM, Ernst SJ, Rose A, Najjar YG, Belkaid Y, Kirkwood JM, Trinchieri G, Zarour HM. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2021;371:595-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 843] [Cited by in RCA: 1205] [Article Influence: 241.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Pomej K, Frick A, Scheiner B, Balcar L, Pajancic L, Klotz A, Kreuter A, Lampichler K, Regnat K, Zinober K, Trauner M, Tamandl D, Gasche C, Pinter M. Study protocol: Fecal Microbiota Transplant combined with Atezolizumab/Bevacizumab in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma who failed to achieve or maintain objective response to Atezolizumab/Bevacizumab - the FAB-HCC pilot study. PLoS One. 2025;20:e0321189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Pomej K, Frick A, Scheiner B, Balcar L, Pajancic L, Klotz A, Regnat K, Zinober K, Trauner M, Tamandl D, Gasche C, Pinter M. TOP-488-YI Fecal microbiota transplant combined with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab-interim analysis of the FAB-HCC phase II pilot study. J Hepatol. 2024;80:S436-S437. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/