Published online Jan 14, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i2.114222

Revised: November 13, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: January 14, 2026

Processing time: 119 Days and 12.8 Hours

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic and debilitating inflammatory bowel disease. Cumulative evidence indicates that excess hydrogen peroxide, a potent neutrophilic chemotactic agent, produced by colonic epithelial cells has a causal role leading to infiltration of neutrophils into the colonic mucosa and subsequent de

Presented is a 41-year-old female with a 26-year history of refractory UC. Having developed steroid dependence and never achieving complete remission on treatment by conventional and advanced therapies, she began treatment with oral R-dihydrolipoic acid (RDLA), a lipid-soluble reducing agent with intracellular site of action. Within a week, rectal bleeding ceased. She was asymptomatic for three years until a highly stressful experience, when she noticed blood in her stool. RDLA was discontinued, and she began treatment with oral sodium thiosulfate pentahydrate (STS), a reducing agent with extracellular site of action. After a week, rectal bleeding ceased, and she resumed oral RDLA and discontinued STS. To date, she remains asymptomatic with normal stool calprotectin while on RDLA.

STS and RDLA are reducing agents that serve as highly effective and safe therapy for the induction and maintenance of remission in UC, even in patients refractory or poorly controlled by conventional and advanced therapies. Should preliminary findings be validated by subsequent clinical trials, the use of reducing agents could potentially prevent thousands of colectomies and represent a paradigm shift in the treatment of UC.

Core Tip: Reducing agents, sodium thiosulfate and R-dihydrolipoic acid, are safe and highly effective to induce and maintain remission of ulcerative colitis, respectively, without the need for immunosuppressive drugs, even in patients who are refractory or poorly controlled by conventional and advanced therapies.

- Citation: Sylvestre PB. Reducing agents for induction and maintenance therapy achieve long-term remission of refractory ulcerative colitis: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(2): 114222

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i2/114222.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i2.114222

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic, debilitating, and progressive inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by the initial influx of neutrophils (innate “first responder” inflammatory cells) infiltrating the lamina propria of the large intestine and transmigrating across the epithelial lining into the crypts of Lieberkühn, forming crypt abscesses[1]. Following disease initiation typically beginning in the rectum and extending proximally, the resulting mucosal inflammation leads to relapsing and remitting bouts of abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea that can persist for weeks to months or years.

Despite decades of research and the introduction of biologics and small molecule (“advanced”) therapies, long-term outcomes for a significant proportion of UC patients - such as long-term sustained remission and avoidance of surgery - remain disappointingly inadequate, underscoring the need for more effective agents that address the underlying cause of disease. Remission rates continue to range between 30% and 40% with most advanced therapies, colectomy rates are not decreasing, and similar hospitalization and disease progression rates are seen compared to cohorts from 20 years ago[2].

Despite the emerging trend for early and frequent use of biologic therapies for the management of severe UC, biologics have not significantly reduced the need for surgery in this patient population[3]. Biological agents and small-molecule therapies in development do not provide reassurance. Remission rates of patients with UC given new therapeutic agents in induction trials have reached a therapeutic ceiling of 20%-30%, signaling the need for a new therapeutic approach in treating UC[4].

Although attributed to “immune dysregulation”, research since the 1950s has failed to identify any pre-existing immune abnormalities in UC patients or their first-degree relatives. On the contrary, basic immune function tests of UC patients show no significant differences compared to healthy controls[5]. Cumulative clinical and experimental evidence indicates that inappropriate secretion of H2O2 (a potent neutrophilic chemotactic agent) by colonic epithelial cells (colonocytes) has a causal role in the pathogenesis of UC[6,7]. Reducing agents that can be delivered to appropriate sites to neutralize colonic H2O2 are able to effectively resolve the underlying stimulus causing UC. In the context of this report, a reducing agent is a therapeutic molecule that neutralizes H2O2 by donating electrons.

This case report describes the long-lasting resolution of UC in a female patient with a 26-year history of refractory disease, achieved through treatment with sodium thiosulfate pentahydrate (STS) and R-dihydrolipoic acid (RDLA), reducing agents capable of scavenging colonic H2O2. This is the first known case of a relapse of UC being successfully treated solely with reducing agents.

A 41-year-old female with a 26-year history of UC presented with rectal pain and bleeding, tenesmus, bowel urgency, and diarrhea.

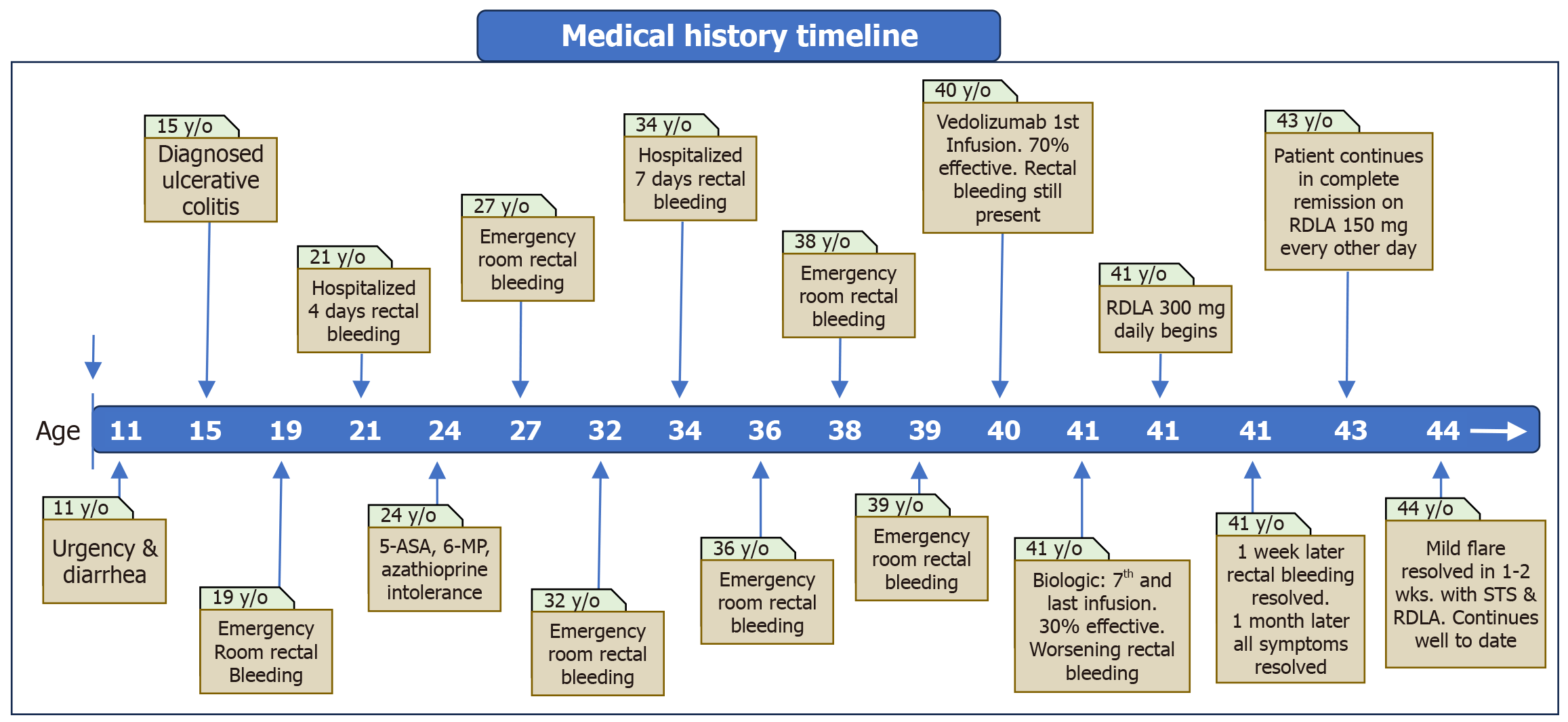

Although formally diagnosed with UC at age 15 after developing abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea, the patient exhibited symptoms as early as age 11, including bowel urgency and frequent daily bowel movements. While initially clinically responsive to combined oral and rectal 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), the effectiveness of these medications waned, and her condition progressively worsened, culminating in a visit to a local emergency department at age 19, the first of multiple emergency department visits due to severe rectal bleeding. Despite the use of multiple 5-ASA formulations, 6-mercaptopurine, and azathioprine over subsequent years, she did not achieve clinical remission and eventually became steroid dependent after developing intolerance to these agents. In addition to multiple visits to emergency departments for intravenous corticosteroids to control worsening rectal bleeding, she was hospitalized twice for severe UC and was repeatedly advised to undergo a total proctocolectomy, which she declined each time. Nine months before her presentation at age 40, she began a series of monthly intravenous infusions of vedolizumab to manage rectal bleeding. Initially, she reported a 70% symptomatic response with decreased rectal bleeding; however, by the seventh and final infusion, her improvement had diminished to only 30% symptomatic response accompanied by worsening rectal bleeding. At the time of presentation, one month following her last vedolizumab infusion, the patient reported experiencing rectal pain and bleeding, tenesmus, bowel urgency, and diarrhea. By this time, now 41 years old, she was taking oral corticosteroids to control rectal bleeding and related not being able to tolerate the side effects of severe fatigue and generalized malaise lasting several days after each vedolizumab infusion, prompting her to seek an alternative form of treatment aside from surgery (total proctocolectomy).

Past medical history includes psoriasis, giardiasis, and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

No alcohol, tobacco, or drug use. No family history of IBD.

The patient was of average build with normal and stable vital signs. Weight of 103 pounds, and body mass index of 18.9 kg/m2. Physical exam was unremarkable.

Complete blood count study and comprehensive metabolic panel were within normal limits.

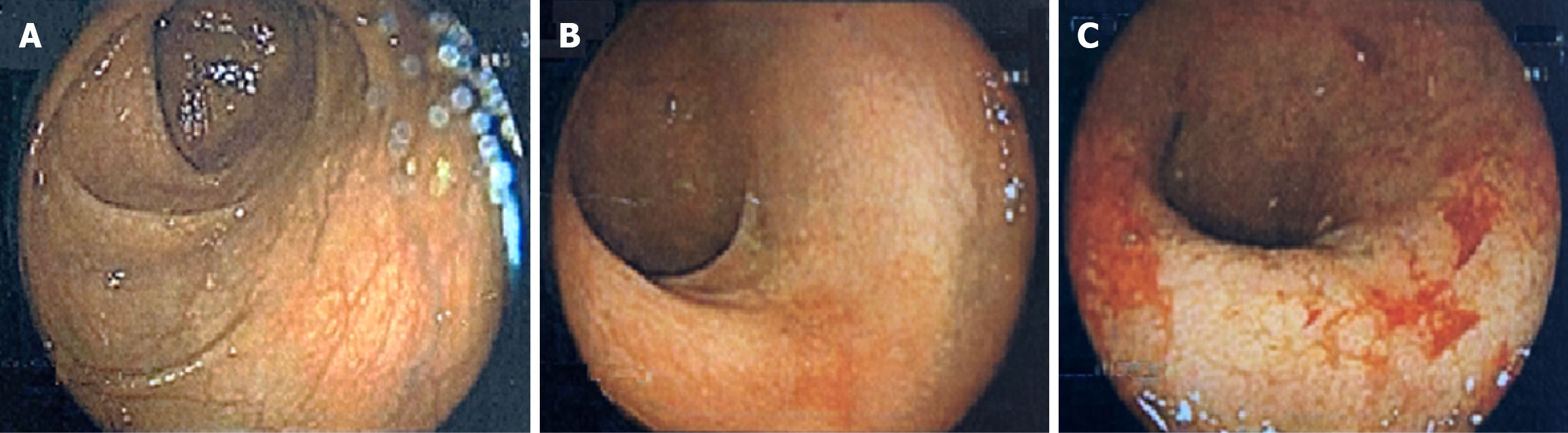

Colonoscopy: Performed at age 40 (prior to treatment with vedolizumab and approximately one year prior to presentation) while managing UC with only oral corticosteroids, colonoscopy showed diffuse, continuous erythema and mucosal friability up to 20 cm with conspicuous erosions and ulceration within the rectum (Figure 1). The proximal colon and terminal ileum were endoscopically unremarkable.

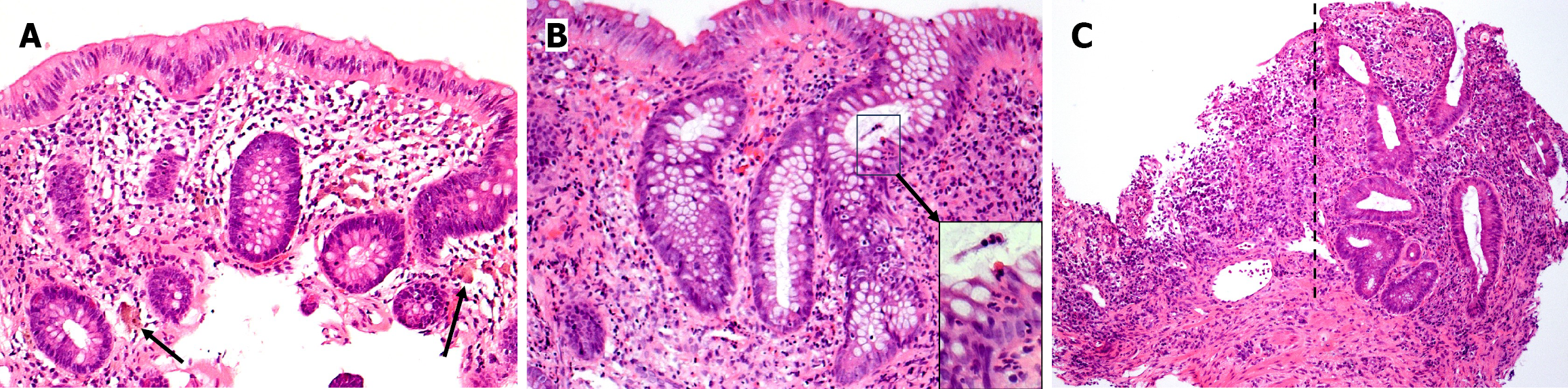

Histopathology: Endoscopic biopsies, obtained during colonoscopy at age 40 while managing UC with only oral corticosteroids, revealed active chronic colitis with crypt architectural distortion within the left colon and rectum (Figure 2). Histologically, the degree of activity is more pronounced in the rectal biopsy and includes areas of ulceration. Inflammation is essentially limited to the mucosa. No skip areas or granulomas are identified. Collectively, the histologic findings are morphologically consistent with the clinical history of UC.

Refractory left-sided UC.

The patient commenced treatment with 300 mg of RDLA PO daily. Within one-week, rectal bleeding ceased. After a month, the debilitating symptoms of rectal pain, tenesmus, bowel urgency, and diarrhea that had plagued her since childhood resolved. The patient received detailed counseling on identifying and avoidance of environmental oxidative stressors, including lifestyle modification, dietary changes, and stress reduction. Three months after initiating treatment, RDLA dosage was reduced from 300 mg daily to 300 mg every other day. This regimen was maintained for an additional three months, after which it was further reduced to 150 mg every other day, successfully alleviating mild sleep disturbance attributed to RDLA while maintaining complete remission of UC. Three months later, RDLA dosage was further reduced to 150 mg every third day. The patient continues to be in good health and asymptomatic with normal bowel movements on this reduced dosage of RDLA.

Laboratory tests performed 15 months after beginning RDLA treatment were all within normal limits, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel, C-reactive protein of 0.2 mg/L (reference: < 8 mg/L), and stool calprotectin of 10 μg/g (reference: < 50 μg/g). The patient declined a follow-up colonoscopy. After 3 years of feeling completely well with normal bowel movements on RDLA treatment, the patient developed a mild UC flare during a stressful and life-threatening experience from the onslaught of Hurricane Helene that caused calamitous damage across the Southeastern United States in September 2024. After fleeing for safety amidst escalating floodwaters, the patient noticed blood in her stool. Increasing the dose of RDLA exacerbated her symptoms. In response, the patient discontinued RDLA and began a daily course of oral STS. Within a few days, rectal bleeding ceased, and after one week, she discontinued STS and resumed her previous regimen of RDLA. As of the date of this case report (one year later), she remains asymptomatic with normal bowel movements while on RDLA. A summary of the patient’s medical history of UC is presented in visual timeline (Figure 3).

The patient in this case report referred to her struggle with refractory UC as a “26-year flare”, indicating that she never felt completely well, having suffered most of her life with this disease. After failing medical therapy, including multiple 5-ASA formulations, steroids, 6-mercaptopurine, and biologics, treatment with RDLA (Redox Bioscience[6]) - a bio-membrane-permeable, lipid-soluble, intracellular, H2O2 reducing agent[7] - was initiated. RDLA completely resolved her rectal bleeding, tenesmus, and bowel urgency within weeks. The treatment of UC with reducing agents is supported by evidence indicating that excess production of H2O2 by colonocytes has a causal role in the development of this disease[8,9]. H2O2 is a powerful neutrophilic chemotactic agent that can cross the cell membrane by passive diffusion. When produced in excess, H2O2 can “leak” out of colonocytes and initiate migration of intravascular neutrophils into the lamina propria, colonic epithelium, and crypts of Lieberkühn, resulting in mucosal inflammation and, as it persists, the development of UC. The administration of RDLA effectively abrogates the H2O2-mediated chemotactic signal, halting the migration of neutrophils and resolving the colitis indefinitely, provided that the dosage is sufficient to prevent excess colonocyte H2O2 from diffusing into the extracellular space. Studies have shown that neutrophils are capable of detecting, responding to, and migrating towards an increasing H2O2 concentration gradient as small as 100 picomolar - equivalent to a differential of approximately five H2O2 molecules between the leading and trailing edges of the cell[10]. This represents the molecular basis of the disease and marks a critical transition point where redox-driven pathogenesis evolves into a pathophysiological state characterized by neutrophil-mediated inflammation, ultimately culminating in UC.

Should this mechanism of disease be validated, this therapeutic approach would represent a functional cure, as RDLA supplies the necessary reducing equivalents for colonocytes to maintain normal redox homeostasis and prevent pathologic intracellular accumulation of H2O2, thereby averting H2O2 diffusion into the extracellular space.

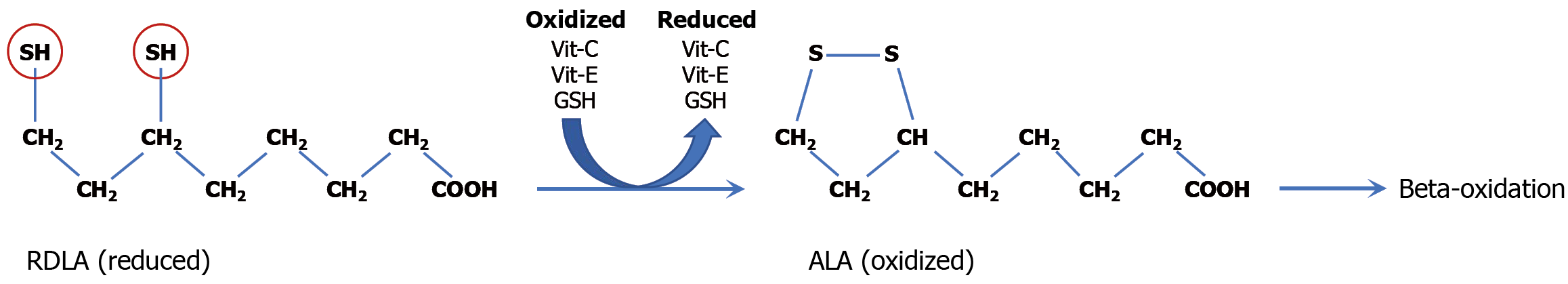

RDLA is naturally found in cells and synthesized endogenously[11]. It functions as a coenzyme in mitochondrial energy metabolism and acts as a potent antioxidant capable of regenerating other endogenous antioxidants (such as vitamin C, vitamin E, glutathione, and thioredoxin)[11]. The sustained remission of UC achieved with orally administered RDLA is attributed to two critical physicochemical properties: Its ability to permeate cell membranes and its markedly low redox potential, making it a potent antioxidant[12]. Structurally, RDLA features an aliphatic eight-carbon backbone terminating in a carboxylic acid group at one end and two thiol groups at the opposite end, rendering the molecule fully reduced (Figure 4). Its amphipathic nature, conferred by the lipophilic carbon chain and hydrophilic carboxyl group, facilitates both lipid and water solubility, respectively[13]. Consequently, RDLA is efficiently absorbed via oral administration, circulates through the bloodstream, and readily diffuses through colonic epithelial cell membranes[13]. Upon entry into epithelial cells and subsequent transport into mitochondria, RDLA enhances cellular reductive capacity, promoting neutralization of H2O2[13].

The principal therapeutic role of RDLA is to function as a biological reducing agent that enhances the body’s intrinsic reductive (antioxidant) defenses. The thiol groups are responsible for the electron donating (antioxidant) capacity of RDLA[14]. RDLA has a redox potential of -320 mV, markedly lower than that of glutathione (-240 mV) and thioredoxin (-230 mV)[15-17]. This lower redox potential enables RDLA to effectively donate electrons for the regeneration of other cellular antioxidants - including vitamin C, vitamin E, glutathione, and thioredoxin - following their utilization in neutralizing intracellular and intramitochondrial H2O2[6]. While RDLA can directly react with H2O2 to form two molecules of water (H2O), its primary therapeutic mechanism centers on its ability to supply needed reducing equivalents (electrons) to enhance cellular reductive capacity within colonocytes to enable neutralization of excess intracellular H2O2. In other words, RDLA supplies electrons that contribute to the replenishment of reduced glutathione and thioredoxin, which together play an indispensable role in H2O2 neutralization. After electron donation, the oxidized RDLA forms alpha lipoic acid (ALA), which may be recycled back to RDLA but is eventually metabolized via mitochondrial beta-oxidation[14]. RDLA’s amphipathic molecular structure and reductive capacity to fortify cellular redox balance underly its ability to maintain long-term remission of UC.

To be effective, administered RDLA must cross the extracellular space and enter the colonocytes in its biologically active reduced state. However, during active colonic inflammation, both neutrophils and colonocytes secrete H2O2 into the colonocyte extracellular space. The presence of extracellular H2O2 can oxidize RDLA to its inactive form, ALA, before absorption by colonocytes, thereby rendering RDLA ineffective. Once inside the colonocytes, ALA can be converted back to RDLA by thioredoxin disulfide reductase (EC 1.8.1.9)[18]. However, conversion of ALA to RDLA results in no net increase in colonocyte reductive capacity. Thioredoxin disulfide reductase is a critical enzyme needed to reduce (neutralize) H2O2 in the cell[19]. As such, the introduction of ALA into the colonocytes diverts reducing equivalents away from the reduction of H2O2, which can lead to an increase in colonocyte H2O2 levels and, as a consequence, exacerbate UC as accumulated H2O2 diffuses out of the colonocytes.

To prevent the oxidation of administered RDLA to ALA prior to entering the colonocytes, the extracellular H2O2 present in the colonic mucosa during active UC must be first neutralized. This step can be thought of as induction. The neutralization of extracellular H2O2 will abrogate the H2O2-mediated neutrophilic chemotactic signal attracting neutrophils into the colonic mucosa, resulting in cessation of inflammatory activity. Although immunosuppressive agents such as steroids and biologics have been used to decrease the immune response and, thereby, lower the extracellular H2O2 delivered by inflammatory cells, these agents do not address excess H2O2 diffusing from the colonic epithelium. An extracellular reducing agent such as STS can be used to neutralize H2O2 in the extracellular space, irrespective of its origin.

The use of the reducing agent RDLA to successfully treat UC, including refractory UC, has been previously demon

In patients whose colonic inflammation has been partially resolved through traditional and/or advanced therapies, extracellular H2O2 levels in the colonic epithelial extracellular space may be sufficiently reduced to allow initiation of treatment with RDLA without preceding STS administration. This patient’s initial transition to RDLA following partial resolution with vedolizumab therapy serves as a representative example of this scenario.

The optimal dose and frequency of STS have not been determined for induction of remission of UC. A starting dose of STS of 625 mg [1/8th teaspoon of STS (Na2S2O3∙5H2O) 99.5% pure, fine crystal, ChemCenter[23]] dissolved in 2-4 ounces of distilled water and consumed orally once or twice daily has been shown to resolve rectal bleeding and restore normal bowel movements within one week in several patients with UC uncomplicated by a co-existing condition (i.e., bacterial infection). An increased dose of STS may be necessary based on patient assessment. Sodium thiosulfate is available in the pentahydrate and anhydrous forms. The pentahydrate form (used in the treatment of UC) is a translucent crystalline compound that readily dissolves in water, making it suitable for oral administration. The standard redox potential of STS is approximately +169 mV, which ensures a spontaneous reduction of H2O2, whose redox potential is +1770 mV. The overall chemical reaction is as follows: Na2S2O3 + 4 H2O2 → 2 NaHSO4 + 3 H2O.

In the aqueous environment of the colonic tissue, STS (Na2S2O3) reacts with H2O2 in a redox process where thiosulfate is oxidized (donates electrons) and H2O2 is reduced (receives electrons). This reaction yields sodium bisulfate (NaHSO4) and water molecules (H2O). This interaction demonstrates the reductive potential of STS in biological settings and its use as a therapeutic reducing agent.

Roughly 10% of orally administered STS is absorbed within the gastrointestinal tract and is quickly dispersed via the systemic circulation throughout extracellular fluid, including the colonic lamina propria, where it neutralizes extracellular H2O2. This abrogates H2O2 mediated neutrophilic chemotaxis, suppressing neutrophil recruitment and inflammation in UC and leading to remission. Due to its systemic distribution, STS can be effective in pan-UC; as such, administration via enema is not necessary. Hepatic metabolism and renal excretion are the main routes of elimination of STS with a reported serum half-life of approximately 30-180 minutes in healthy volunteers, depending on the dose[24]. The unabsorbed fraction of STS remaining in the gastrointestinal tract likely also plays a therapeutic role, as it can neutralize H2O2 directly within the lumen of the colon and along the luminal surface of the colonic epithelium. This dual distribution and sites of action by STS differs from conventional oral and rectal formulations of 5-ASA, which typically exert their effects exclusively from the luminal side of the large intestine.

Currently, 5-ASA is typically used as first-line therapy for induction of remission in mild-to-moderate UC. Both STS (+169 mV) and 5-ASA (approximately +564 mV) have redox potentials far below that of H2O2 (+1770 mV), making the reduction (neutralization) of H2O2 by these agents thermodynamically favorable[25-27]. STS exhibits superior efficacy in neutralizing H2O2 compared to 5-ASA, owing to STS’s lower redox potential (stronger reducing agent) and its direct two-electron reduction mechanism that rapidly donates electrons to convert H2O2 into harmless byproducts.

Because 5-ASA relies on enzyme-dependent activation with colonic luminal peroxidase for optimal neutralization of

It is noteworthy that while H2O2 appears to be the most prevalent chemotactic agent secreted by colonocytes leading to the manifestation of UC, it is not the sole chemoattractant that can cause this inflammatory pattern. UC emerging in the context of systemic or chronic immune activation may suggest involvement of a non-H2O2 chemotactic pathway, potentially responsive to currently available cytokine antagonists. This pathogenetic heterogeneity of UC is supported by a case report of refractory UC that completely resolved with anakinra, an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist[29]. Thus, the therapeutic focus in the treatment of UC should be on identifying and targeting the specific inciting chemotactic agent rather than generically suppressing the immune response. In this context, STS may serve both diagnostic and therapeutic (“theranostic”) roles. This can be paired with advanced imaging techniques to hasten diagnosis[30,31]. Successful remission following STS initiation implicates H2O2 as the chemotactic factor responsible for UC development. Conversely, a lack of response to STS suggests that other oxidative stressors are likely to be present (i.e., infection, ischemia-reperfusion injury) or H2O2 is not the responsible chemotactic agent. In such cases, further investigations should be conducted to identify other potential chemotactic agents and alternative or concurrent treatable etiologies before resorting to surgery.

A positive response to STS implies that excess colonic H2O2 is a primary etiological agent in the patient’s UC and that favorable outcomes can be anticipated following transition to RDLA. Induction of remission with STS (cessation of rectal bleeding, resolution of diarrhea, etc.) signals substantial elimination of H2O2, after which transition to RDLA can commence. Transition to RDLA (typical starting dose of 200 mg PO daily in the morning) may commence within days after starting STS, provided the patient has shown resolution of rectal bleeding and restoration of normal bowel movements with STS treatment. Patients have tolerated the discontinuation of STS on the day RDLA treatment is initiated; however, if a more gradual transition is warranted, RDLA can be added while STS is weaned. Both agents may occasionally be needed indefinitely for individuals producing large amounts of colonocyte H2O2. Reducing agents are best taken on an empty stomach, if possible, to prevent oxidation by stomach contents. To avoid potential RDLA oxidation by STS, these reducing agents should be administered 12 hours apart (RDLA in the morning, STS in the evening) when used together. A conservative approach to RDLA dose reduction was employed for the patient in this case report. The timeline for dosage reduction may be accelerated based upon clinical response until the minimum effective dose needed to prevent relapse is established.

STS is an odorless, water-soluble, small inorganic molecule (molecular weight of 158.11 g/mol) that is normally produced in mitochondria as a product of sulfide oxidation pathways[32]. STS is a direct-acting reducing agent that can donate two electrons to chemically neutralize H2O2 upon contact[33]. Because STS does not depend upon biological antioxidant enzyme systems for its therapeutic action, it can rapidly reduce H2O2 and restore redox homeostasis in critical settings such as acute or severe UC. The United States Food and Drug Administration has approved STS to treat cyanide poisoning and to reduce ototoxicity in pediatric patients undergoing chemotherapy with cisplatin. Various off-label uses of STS include treatment of cystinuria, calciphylaxis, and neurodegenerative diseases[34]. STS is generally considered safe based on approved therapeutic dosing guidelines and is on the World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines[35]. Oral STS is generally well tolerated. A compilation of case series of long-term oral STS (for calcific uremic arteriolopathy, recurrent renal stones, nephrocalcinosis, and tumoral calcinosis), with dosing up to 5 g daily for up to 18 years, reported a range of no side effects to mild side effects consisting of loose or foul-smelling stools[36]. Metabolic acidosis has been reported after a 25 g intravenous infusion of STS for calcific uremic arteriolopathy in a patient with end stage renal disease on hemodialysis[37]. Remembering that roughly only 10% of orally administered STS is absorbed within the gastrointestinal tract, this intravenous infusion of STS was far in excess to the oral dosing equivalent used in the treatment of UC flares and other conditions, as detailed above.

RDLA is the reduced form of R-ALA, a small 6-carbon organic molecule which occurs naturally in most eukaryotic cells, including human cells, and serves as an essential co-factor for several enzymes involved in energy metabolism. R-ALA, the oxidized form of RDLA, is ubiquitous in nature and is found in the human diet in animal tissue, fruits, and vegetables. Once inside cells, R-ALA is reduced to RDLA, which possesses two thiol groups absent in R-ALA. These thiol groups confer RDLA with significant antioxidant activity, making it the biologically active form responsible for cellular antioxidant protection[38]. Due to its lower production cost and greater stability, ALA is the form most commonly available in dietary supplements, with synthetic forms of ALA comprised of both the S and R isomers. Consequently, ALA is the form frequently utilized in research settings to evaluate toxicity and pharmacokinetics. However, for therapeutic applications - particularly in conditions characterized by H2O2 induced oxidative stress such as UC - only the reduced form, RDLA, offers therapeutic benefit. RDLA enhances the cell’s reductive capacity and offers targeted antioxidant protection against H2O2. ALA exhibits favorable human safety properties with a well-documented safety profile and tolerability in many in vivo studies and clinical trials[39]. Animal studies in which rats were administered 180 g/kg/day of body weight for a period of two years showed no difference between control and treated animals with respect to body weight gain, food consumption, behavioral effects, hematological and clinical chemistry parameters, and gross and histological parameters. The administered dose in this animal study is approximately 20 times greater than the average human dose of 600 mg/day for a 70 kg human or 8.5 mg/kg/day of body weight[40]. The study demonstrated that ALA is without carcinogenic potential at dosing up to 180 g/kg/day of body weight and demonstrated no target organ toxicity. The no-observed adverse level is considered to be 60 mg/kg/day of body weight or approximately 7 times the average human daily dose[38]. ALA did not show mutagenicity in Ames assays nor was there any evidence of chromosomal damage in the in vivo mouse micronucleus assay. The acute oral LD50 in rats was found to be in excess of 2000 mg/kg[38]. In general, ALA supplementation in humans has been found to have few serious side effects. Intravenous administration of racemic ALA at doses of 600 mg/day for 3 weeks and oral racemic ALA at doses as high as 1800 mg/day for 6 months and 1200 mg/day for 2 years did not result in serious adverse effects when used to treat diabetic peripheral neuropathy[40,41]. Two minor anaphylactoid reactions and one severe anaphylactic reaction, including laryngospasm, were reported after intravenous ALA administration[42]. The most frequently reported side effects to oral ALA supplementation are allergic reactions affecting the skin, including rashes, hives, and itching. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, have also been reported. Malodorous urine has also been noted by people taking 1200 mg/day of ALA orally[43]. ALA was well tolerated with no serious events reported in a study administering up to 1800 mg daily for 4 weeks[44]. Moderate gastric pain was reported in 2 of 14 individuals taking 1800 mg three times daily for up to 6 months[45]. ALA was well tolerated in a study conducted over a period of 4 months with 39 individuals receiving 800 mg of oral ALA daily[45,46]. Adverse effects in individuals receiving 600 mg of ALA daily were found to be less than placebo in a study of 328 individuals receiving daily intravenous ALA in a 3-week multicenter, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study[47].

Evidence indicates that excess colonocyte H2O2 is a primary etiological agent in the development of UC. Effective treatment requires the targeted therapeutic reduction of H2O2 using appropriate reducing agents. Reducing agents supply colonocytes with the deficient reducing equivalents needed to maintain normal intracellular H2O2 levels, thereby realizing a functional cure by preserving normal colonocyte redox homeostasis. As demonstrated herein, reducing agents STS and RDLA are highly effective induction and maintenance therapy, respectively, for achieving long-term remission of UC and restoring normal quality of life. Reducing agents can be effective even in patients who are refractory or poorly controlled by conventional and advanced therapies. RLDA induced remission is sustained as long as excess H2O2 does not accumulate in colonocytes and diffuse into the extracellular space, as may occur when an oxidative stressor increases colonocyte H2O2 above a patient’s baseline reductive capacity. The reducing agents STS and RDLA used to treat UC are efficacious and inexpensive and have no known significant side effects. This breakthrough opens a pathway towards inexpensive treatment with functionally curative potential. Should preliminary findings be validated by subsequent robust clinical trials, the use of reducing agents in treating UC could potentially prevent thousands of colectomies and signal a paradigm shift in the treatment of UC.

I extend my sincere gratitude to Dr. Jay Pravda for his mentorship in advancing my understanding of redox biology. His guidance and expertise have been invaluable in shaping my understanding of oxidative and reductive processes in health and disease states. It is an honor to present this case report that underscores the significance of Dr. Pravda’s pioneering work with reducing agents in the treatment of ulcerative colitis.

| 1. | Porter RJ, Kalla R, Ho GT. Ulcerative colitis: Recent advances in the understanding of disease pathogenesis. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-F1000 Faculty 294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aslam N, Lo SW, Sikafi R, Barnes T, Segal J, Smith PJ, Limdi JK. A review of the therapeutic management of ulcerative colitis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221138160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wong DJ, Roth EM, Feuerstein JD, Poylin VY. Surgery in the age of biologics. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2019;7:77-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alsoud D, Verstockt B, Fiocchi C, Vermeire S. Breaking the therapeutic ceiling in drug development in ulcerative colitis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:589-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Triantafillidis JK, Economidou J, Manousos ON, Efthymiou P. Cutaneous delayed hypersensitivity in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Application of multi-test. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:536-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Digestive Warrior. R-Dihydrolipoic Acid (RDLA) By Redox BioScience. [cited 31 August 2025]. Available from: https://digestivewarrior.com/products/r-dihydrolipoic-acid-99-pure-by-redox-bioscience. |

| 7. | Packer L, Kraemer K, Rimbach G. Molecular aspects of lipoic acid in the prevention of diabetes complications. Nutrition. 2001;17:888-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Santhanam S, Venkatraman A, Ramakrishna BS. Impairment of mitochondrial acetoacetyl CoA thiolase activity in the colonic mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2007;56:1543-1549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pravda J. Evidence-based pathogenesis and treatment of ulcerative colitis: A causal role for colonic epithelial hydrogen peroxide. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:4263-4298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 10. | Morad H, Luqman S, Tan CH, Swann V, McNaughton PA. TRPM2 ion channels steer neutrophils towards a source of hydrogen peroxide. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Navari-Izzo F, Quartacci MF, Sgherri C. Lipoic acid: a unique antioxidant in the detoxification of activated oxygen species. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2002;40:463-470. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Dieter F, Esselun C, Eckert GP. Redox Active α-Lipoic Acid Differentially Improves Mitochondrial Dysfunction in a Cellular Model of Alzheimer and Its Control Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:9186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Superti F, Russo R. Alpha-Lipoic Acid: Biological Mechanisms and Health Benefits. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024;13:1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Biewenga GP, Haenen GR, Bast A. The pharmacology of the antioxidant lipoic acid. Gen Pharmacol. 1997;29:315-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 577] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Suh JH, Zhu BZ, deSzoeke E, Frei B, Hagen TM. Dihydrolipoic acid lowers the redox activity of transition metal ions but does not remove them from the active site of enzymes. Redox Rep. 2004;9:57-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Aslund F, Berndt KD, Holmgren A. Redox potentials of glutaredoxins and other thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases of the thioredoxin superfamily determined by direct protein-protein redox equilibria. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30780-30786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mallikarjun V, Clarke DJ, Campbell CJ. Cellular redox potential and the biomolecular electrochemical series: a systems hypothesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:280-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Arnér ES, Nordberg J, Holmgren A. Efficient reduction of lipoamide and lipoic acid by mammalian thioredoxin reductase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;225:268-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cox AG, Winterbourn CC, Hampton MB. Mitochondrial peroxiredoxin involvement in antioxidant defence and redox signalling. Biochem J. 2009;425:313-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pravda J, Weickert MJ, Wruble LD. Novel Combination Therapy Induced Histological Remission in Patients with Refractory Ulcerative Colitis. J Inflam Bowel Dis Disor. 2019;4:130. |

| 21. | Pravda J, Gordon R, Sylvestre PB. Sustained Histologic Remission (Complete Mucosal Healing) 12 Years after One-Time Treatment of Refractory Ulcerative Colitis with Novel Combination Therapy: A Case Report. J Inflam Bowel Dis Disor. 2020;5:132. |

| 22. | Sauk JS, Ryu HJ, Labus JS, Khandadash A, Ahdoot AI, Lagishetty V, Katzka W, Wang H, Naliboff B, Jacobs JP, Mayer EA. High Perceived Stress is Associated With Increased Risk of Ulcerative Colitis Clinical Flares. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:741-749.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | RND Center Inc.. Sodium Thiosulfate, Fine Crystal, Reagent, 500 grams. [cited 31 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.rndcenterinc.com/shop/p/sodium-thiosulfate-500-grams. |

| 24. | Farese S, Stauffer E, Kalicki R, Hildebrandt T, Frey BM, Frey FJ, Uehlinger DE, Pasch A. Sodium thiosulfate pharmacokinetics in hemodialysis patients and healthy volunteers. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1447-1455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Goyal B, Solanki S, Arora S, Prakash A, Mehrotra RN. Kinetics and mechanism of the oxidation of thiosulfate ion by hexachloroiridate(IV). J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1995;3109-3112. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Nigović B, Simunić B. Determination of 5-aminosalicylic acid in pharmaceutical formulation by differential pulse voltammetry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2003;31:169-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Drogui P, Elmaleh S, Rumeau M, Bernard C, Rambaud A. Oxidising and disinfecting by hydrogen peroxide produced in a two-electrode cell. Water Res. 2001;35:3235-3241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | El Zein R, Ispas-Szabo P, Jafari M, Siaj M, Mateescu MA. Oxidation of Mesalamine under Phenoloxidase- or Peroxidase-like Enzyme Catalysis. Molecules. 2023;28:8105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Truyens M, Hoste L, Geldof J, Hoorens A, Haerynck F, Huis In 't Veld D, Lobatón T. Successful treatment of ulcerative colitis with anakinra: a case report. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2023;86:573-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chou CK, Lee KH, Karmakar R, Mukundan A, Chen TH, Kumar A, Gutema D, Yang PC, Huang CW, Wang HC. Integrating AI with Advanced Hyperspectral Imaging for Enhanced Classification of Selected Gastrointestinal Diseases. Bioengineering (Basel). 2025;12:852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tsai TJ, Lee KH, Chou CK, Karmakar R, Mukundan A, Chen TH, Gupta D, Ghosh G, Liu TY, Wang HC. Enhancing Early GI Disease Detection with Spectral Visualization and Deep Learning. Bioengineering (Basel). 2025;12:828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhang MY, Dugbartey GJ, Juriasingani S, Sener A. Hydrogen Sulfide Metabolite, Sodium Thiosulfate: Clinical Applications and Underlying Molecular Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:6452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bijarnia RK, Bachtler M, Chandak PG, van Goor H, Pasch A. Sodium thiosulfate ameliorates oxidative stress and preserves renal function in hyperoxaluric rats. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mcgeer PL, McGeer EG, Lee M. Medical uses of Sodium thiosulfate. J Neurol Neuromedicine. 2016;1:28-30. |

| 35. | World Health Organization. The selection and use of essential medicines, 2025: WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, 24th list. [cited 31 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/B09474. |

| 36. | AlBugami MM, Wilson JA, Clarke JR, Soroka SD. Oral sodium thiosulfate as maintenance therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy: a case series. Am J Nephrol. 2013;37:104-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hunt GM, Ryder HF. Metabolic acidosis after sodium thiosulfate infusion and the role of hydrogen sulfide. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6:1595-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Cremer DR, Rabeler R, Roberts A, Lynch B. Safety evaluation of alpha-lipoic acid (ALA). Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2006;46:29-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Cremer DR, Rabeler R, Roberts A, Lynch B. Long-term safety of alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) consumption: A 2-year study. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2006;46:193-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ziegler D, Nowak H, Kempler P, Vargha P, Low PA. Treatment of symptomatic diabetic polyneuropathy with the antioxidant alpha-lipoic acid: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2004;21:114-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Reljanovic M, Reichel G, Rett K, Lobisch M, Schuette K, Möller W, Tritschler HJ, Mehnert H. Treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy with the antioxidant thioctic acid (alpha-lipoic acid): a two year multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial (ALADIN II). Alpha Lipoic Acid in Diabetic Neuropathy. Free Radic Res. 1999;31:171-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ziegler D. Thioctic acid for patients with symptomatic diabetic polyneuropathy: a critical review. Treat Endocrinol. 2004;3:173-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Yadav V, Marracci G, Lovera J, Woodward W, Bogardus K, Marquardt W, Shinto L, Morris C, Bourdette D. Lipoic acid in multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Mult Scler. 2005;11:159-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Jacob S, Ruus P, Hermann R, Tritschler HJ, Maerker E, Renn W, Augustin HJ, Dietze GJ, Rett K. Oral administration of RAC-alpha-lipoic acid modulates insulin sensitivity in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus: a placebo-controlled pilot trial. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:309-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Gedlicka C, Kornek GV, Schmid K, Scheithauer W. Amelioration of docetaxel/cisplatin induced polyneuropathy by alpha-lipoic acid. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:339-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Ziegler D, Schatz H, Conrad F, Gries FA, Ulrich H, Reichel G. Effects of treatment with the antioxidant alpha-lipoic acid on cardiac autonomic neuropathy in NIDDM patients. A 4-month randomized controlled multicenter trial (DEKAN Study). Deutsche Kardiale Autonome Neuropathie. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:369-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 47. | Ziegler D, Hanefeld M, Ruhnau KJ, Meissner HP, Lobisch M, Schütte K, Gries FA. Treatment of symptomatic diabetic peripheral neuropathy with the anti-oxidant alpha-lipoic acid. A 3-week multicentre randomized controlled trial (ALADIN Study). Diabetologia. 1995;38:1425-1433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/