Published online Jan 14, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i2.114591

Revised: November 10, 2025

Accepted: November 19, 2025

Published online: January 14, 2026

Processing time: 111 Days and 3.4 Hours

This editorial examines the emerging potential of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in enhancing postoperative recovery following gastroenteroscopy, high

Core Tip: This study highlights the innovative integration of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation and meridian flow injection with traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) principles to enhance gastroenteroscopy recovery, demonstrating significant improvements in gastrointestinal function and stress reduction. Its key contribution lies in proposing a novel evidence-based framework, emphasizing the need for multicenter trials and advanced methodologies to address current challenges in trial design and reporting, thereby advancing the global acceptance of TCM in perioperative care.

- Citation: Zhang JL, You LZ. Evidence-based acupuncture: Methodological insights and challenges in gastroenteroscopy recovery research. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(2): 114591

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i2/114591.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i2.114591

Gastroenteroscopy, encompassing procedures such as gastroscopy and colonoscopy, serves as a cornerstone in the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, with millions of procedures performed globally each year. Despite technological advancements in minimally invasive techniques, postoperative complications remain prevalent, including GI dysfunction characterized by nausea, abdominal distension, delayed defecation, and diminished bowel sounds. These issues not only prolong hospital stays but also exacerbate patient discomfort and healthcare costs. Tradi

In this context, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) emerges as a promising complementary modality, integrating ancient principles with contemporary evidence-based practice. TCM conceptualizes postoperative GI disturbances as manifestations of spleen-stomach disharmony, qi stagnation, and meridian blockages, offering non-pharmacological interventions that target root causes rather than symptoms alone. A notable example is the 2025 randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Hong et al[1], published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology, which explores the efficacy of meridian flow injection (MFI) acupoint application combined with transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation (TEAS) in 120 patients undergoing gastroenteroscopy for benign or precancerous lesions. This study posits that the combined intervention, applied over three days, promotes GI function recovery evidenced by reduced time to first defecation (3.20 ± 1.04 days vs 3.98 ± 1.27 days in controls, P < 0.001) and mitigates stress responses through biomarker improvements, such as elevated gastrin levels and lowered norepinephrine, cortisol, and aldosterone.

The trial’s design involved stratified block randomization, allocating patients to an observation group receiving MFI-TEAS alongside routine care and a control group with routine care plus basic acupoint plastering. Key acupoints targeted included Shenque (CV8), Zhongwan (CV12), Tianshu (ST25), and Zusanli (ST36), with MFI utilizing a herbal paste (Qingpi, Houpu, raw rhubarb in a 2:2:1 ratio, dosed at 0.3 g/cm2) timed according to Ziwu Liuzhu theory, and TEAS delivering biphasic waves at 2/100 Hz for 30 minutes daily. Outcomes extended beyond physiological markers to include higher clinical efficacy rates (93.33% vs 75.00%, P = 0.006), patient satisfaction (91.67% vs 68.33%, P = 0.001), and reduced complication rates (16.67% vs 38.33%, P = 0.008).

This perspective piece, framed as an opinion paper, extends the discourse on Hong et al’s findings by evaluating the trial through six critical scientific lenses[1]: Trial design and registration, adherence to reporting checklists, intervention methods (treatment vs control), the illumination of TCM theory in practice, adverse event (AE) reporting, and the credibility of conclusions in terms of verification and falsifiability. By synthesizing insights from the study and recent literature, this discussion aims to highlight methodological strengths, identify gaps, and propose directions for future research. Such an analysis is timely, given the burgeoning interest in integrative medicine, where TCM modalities like acupuncture and herbal applications are increasingly scrutinized for their role in perioperative care. Recent meta-analyses[2] underscore TEAS’s potential in accelerating postoperative GI recovery across abdominal surgeries, with pooled data showing shortened times to first flatus, first defecation, first bowel movement, and postoperative feeding. Similarly, timing-specific interventions aligned with circadian rhythms, as in MFI, draw from chronopharmacology principles that enhance therapeutic efficacy[2,3].

Ultimately, this perspective advocates for a balanced integration of TCM with Western biomedicine, emphasizing rigorous standards to ensure reproducibility, safety, and clinical translation. Drawing on a proposed “chronobiological integrative paradigm”, this framework philosophically shifts from reductionist Western models to holistic TCM cycles, facilitating a Kuhnian paradigm evolution in medicine where cyclical interrelationships (e.g., five-element dynamics) complement linear causality. As global healthcare systems grapple with rising endoscopy demands and postoperative burdens, innovations like MFI-TEAS could offer patient-centered solutions, provided they withstand methodological scrutiny.

The foundation of any RCT lies in its design, which must balance internal validity with practical feasibility to yield reliable evidence. Hong et al’s study[1] exemplifies this through its single-center, parallel-group framework conducted at Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital from October 2024 to January 2025. Employing stratified block randomization via SAS 9.4 software, the trial allocated 120 patients (aged 18-70, American Society of Anesthesiologists grades I-III) based on lesion types (gastric, colorectal, esophageal), mitigating confounding variables and ensuring baseline comparability (P > 0.05 across demographics and diagnostics). This approach aligns with best practices for minimizing selection bias, as opaque sealed envelopes facilitated allocation concealment by an independent statistician.

Power calculations further bolster the design’s robustness: Using PASS 15 software, the sample size was determined to detect a 0.8-day difference in first defecation time with 80% power at α = 0.05, accounting for a 10% dropout rate though none occurred, enabling full intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. Ethical compliance with the Helsinki Declaration, including institutional review board approval (No. 235) and informed consent, underscores patient protection. These elements contribute to strong internal validity, allowing confident attribution of outcomes to the intervention.

However, a significant limitation is the lack of prospective trial registration on established platforms such as the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry or ClinicalTrials.gov. Although the authors note in the manuscript footnotes that regis

This oversight is not isolated; a 2025 analysis of acupuncture RCTs revealed that only 26.7% were registered prospec

Future designs should incorporate multicenter collaborations to enhance generalizability, as demonstrated in a 2025 meta-analysis of TEAS for postoperative ileus, where multicenter data improved subgroup analyses on comorbidities. Additionally, pragmatic trial elements evaluating real-world implementation could address the study’s short 3-day follow-up, which neglects long-term effects like sustained GI motility or recurrent complications. Blinding, though partial (patients and assessors possibly blinded), remains vulnerable to performance bias from unblinded deliverers.

In opinion, prioritizing registration and scalable designs is imperative for TCM’s credibility in global medicine. By mandating these in journal policies, as ICMJE recommends, researchers can foster accountability, ultimately streng

Transparent reporting is the linchpin of scientific reproducibility, allowing peers to appraise and replicate studies. Hong et al’s RCT adheres partially to the CONSORT 2010 guidelines[1], a framework essential for non-pharmacological interventions. Strengths include explicit sample size justification, ethical details, and statistical methods (t-tests for continuous data, χ2 for categorical, using SPSS 22.0). However, omissions such as a participant flow diagram detailing enrollment, allocation, follow-up, and analysis and explicit mention of ITT principles, though implied by no dropouts, detract from completeness.

For acupuncture-specific reporting, the revised STRICTA guidelines[7], updated on, 2025, as an extension of CONSORT 2025, provide a tailored checklist with six items and 17 sub-items[8]. These emphasize rationale, intervention details, practitioner background, and comparator descriptions, incorporating updates for non-needle modalities like TEAS and chronobiology elements. The trial excels in specifying acupoints with TCM justifications (e.g., Zusanli for spleen-stomach regulation), TEAS parameters (biphasic square waves, 2/100 Hz alternation mimicking dense-disperse modes, intensity 1-3.5 mA based on tolerance), and regimen (30 minutes daily for 3 days). Herbal paste preparation grinding to thick consistency with Huangjiu is detailed, aiding fidelity.

Yet, gaps persist: Practitioner qualifications are vaguely noted via author contributions, omitting expertise levels or training, which STRICTA mandates to account for operator-dependent variability. De qi elicitation a sensory response indicating effective stimulation is unmentioned[9,10], despite its relevance in TEAS for endogenous opioid release. Control group descriptions are adequate but lack depth on rationale for active plastering, potentially confounding interpretation.

A 2025 analysis of acupuncture trial reporting highlighted that incomplete STRICTA adherence, observed in over 40% of studies, hampers meta-analyses by introducing heterogeneity[6]. Similarly, the CARE extension[11] for acupuncture case reports, released July 1, 2025, stresses individualized therapy reporting, relevant for hybrid interventions like MFI-TEAS. Additionally, a 2022 study[12] on acupuncture for functional constipation found moderate reporting completeness, with only five of 17 STRICTA sub-items adequately reported in over 90% of trials, underscoring the need for improved guideline adherence to ensure reproducibility and reduce bias. This suboptimal adherence, particularly in describing intervention details like needle depth or practitioner qualifications, further complicates meta-analytic synthesis and limits the reliability of acupuncture trial outcomes. Hong et al[1] could benefit from these, particularly in rationale depth, where TCM theory is briefly mentioned without evidence synthesis. To enhance reproducibility, future reports should include precise details such as paste formulation, storage, per-patch dose calculations, device model, and operator training (certified acupuncturists with ≥ 5 years experiences and standardized protocols).

In perspective, full compliance with updated STRICTA and CONSORT would elevate TCM research quality, facilitating global harmonization. Journals should enforce these checklists, as incomplete reporting undermines clinical translation. For future trials, integrating digital tools for automated checklist verification could streamline processes, ensuring comprehensive disclosure.

Precise delineation of intervention methods is critical for evaluating therapeutic effects in TCM trials, yet combined interventions often introduce confounding factors that obscure causal mechanisms. In Hong et al’s study[1], the observation group received MFI-TEAS alongside routine perioperative care, while the control group received routine care plus basic acupoint plastering. Routine care included standardized elements such as early mobilization, timed catheter removal, and abdominal massage, establishing a consistent baseline. MFI involved applying a herbal paste (Qingpi for qi regulation, Houpu for dampness resolution, raw rhubarb for purgation; 2:2:1 ratio, 0.3 g/cm2 in 3 cm × 3 cm patches) to acupoints during spleen (9:00-11:00) and stomach (7:00-9:00) meridian peaks, following Ziwu Liuzhu theory, administered four times daily for three days[3,13]. This chronobiological timing aims to align with circadian GI rhythms to enhance transdermal absorption and efficacy. TEAS, delivered via the QX265 device at bilateral Zusanli, used symmetrical biphasic waves at 2/100 Hz to promote opioid and serotonin release, with current adjusted to patient tolerance (mean 3.5 ± 0.8 mA) for 30 minutes daily.

While this specification supports intervention fidelity, the combined MFI-TEAS approach introduces significant methodological challenges. The control group’s acupoint plastering, despite lacking chronobiological timing or electrical stimulation, includes active elements that may confound outcomes, potentially underestimating MFI-TEAS effects. A true placebo (e.g., non-acupoint stimulation or inert paste) would better isolate contributions. Critically, the absence of separate arms for MFI or TEAS alone obscures whether effects are driven by a single component, a common issue in TCM trials. Recent research trends emphasize standalone TEAS studies to clarify efficacy, with minimal focus on combined herbal interventions due to their confounding nature. For instance, a 2024 RCT[14] on TEAS for post-cerebrovascular surgery recovery demonstrated significant improvements in GI motility and immune function using TEAS alone at acupoints like Zusanli (ST36), Neiguan (PC6), etal, without herbal adjuncts, highlighting its independent efficacy. Similarly, a 2025 study[15] on TEAS for postpartum diastasis recti abdominis showed that TEAS alone, without herbal components, significantly reduced interrectus distance and lumbago, underscoring the clarity gained from single-modality designs. Moreover, a 2023 meta-analysis[16] of 10 RCTs (n = 1497) on standalone TEAS for postoperative GI recovery explicitly excluded studies combining TEAS with other TCM modalities to prevent confounding from component interactions. This rigorous design choice isolates TEAS-specific effects and directly illustrates how composite interventions risk inflating effect sizes through unmeasured synergies, reinforcing the methodological superiority of single-modality trials.

From a critical perspective, the reliance on combined interventions, as in Hong et al[1], should be reconsidered given the current research landscape. Standalone TEAS studies, such as a 2025 protocol for geriatric GI tumor patients, employ dismantling designs to parse electrical stimulation effects, revealing that TEAS alone drives most postoperative recovery benefits[17]. These single-modality studies elucidate clear causal pathways, avoiding the confounding variables inherent in combined approaches. Future TCM trials should prioritize standalone TEAS designs, standardize electrical parameters (e.g., 2/100 Hz, < 10 mA), and, if herbs are included, use phytochemical profiling (e.g., anthraquinones in rhubarb) to ensure reproducibility and address dosage-efficacy relationships. Integrating TCM theory here, Ziwu Liuzhu’s meridian flows correlate with biological clock mechanisms, forming a problem-method-theory loop where chronobiological timing enhances methodological precision and theoretical validity.

While TCM theory offers a valuable framework for guiding clinical interventions such as MFI-TEAS, its application in rigorous RCTs must prioritize evidence-based rigor to achieve international consensus. Positive outcomes alone are insufficient; they must be grounded in verifiable, mechanistic evidence to avoid perceptions of mysticism, akin to unverified practices like witchcraft. In Hong et al’s RCT[1], postoperative GI dysfunction is conceptualized as spleen-stomach deficiency causing qi-blood disharmony and meridian stagnation, resulting in delayed motility and stress responses. MFI-TEAS addresses this through the “cultivating earth to generate metal” principle from five-element theory, where timed applications per Ziwu Liuzhu (midnight-noon ebb-flow) synchronize with meridian peaks to harmonize organ functions and restore balance.

The herbal components in MFI support GI tonification: Qingpi regulates qi flow, Houpu resolves dampness, and rhubarb clears heat and promotes purgation, delivered transdermally to enhance bioavailability by bypassing first-pass metabolism. TEAS, meanwhile, engages neural pathways by activating Aδ and C fibers at Zusanli, thereby augmenting vagal tone via the nucleus tractus solitarius, which in turn promotes peristalsis and mitigates hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperactivity[18,19]. This integration aligns TCM’s holistic paradigm with contemporary concepts like the gut-brain axis[20], where acupuncture influences microbiota composition, inflammatory markers, and neurotransmitter dynamics[21,22].

Emerging 2025 evidence supports these mechanisms: Acupuncture has been shown to modulate the microbiota-gut-brain axis in Parkinson’s disease, ameliorating microbial dysbiosis and alpha-synuclein pathology[23]. Similarly, TCM formulations like Zhi-zi-chi decoction[24] target gut-brain interactions to alleviate insomnia by restoring neurotransmitter balance and microbial homeostasis. Nonetheless, the trial’s superficial rationale merely alluding to TCM concepts without evidential synthesis undermines its depth, particularly for global audiences.

From a critical viewpoint, future studies should explicitly elucidate TCM foundations to bridge cultural gaps: For instance, clarify how the five-element theory (wood, fire, earth, metal, water) differs from Western elemental theories (earth, air, fire, water) in emphasizing cyclical interrelationships (e.g., earth generating metal for lung-spleen harmony) vs static compositions; compare Ziwu Liuzhu’s meridian chronobiology to Western chronomedicine, which focuses on circadian rhythms without organ-specific flows, highlighting shared emphasis on timing but distinct metaphysical bases. Although intuitive for Chinese authors, these relationships pose challenges for international readers unfamiliar with five-element dynamics. To enhance accessibility, we recommend incorporating a theoretical model diagram illustrating these interconnections, mechanisms, and evidence-based validations. Robust integration via multi-omics profiling and func

Safety transparency is a cornerstone of clinical trial integrity, particularly for integrative interventions like MFI-TEAS that combine TCM with modern techniques, introducing potential risks that require meticulous documentation. In Hong

Specific risks associated with TEAS, including skin irritation, electrical discomfort, or contraindications (e.g., potential interference with pacemakers or epilepsy), remain unaddressed, contravening the STRICTA guidelines, which mandate comprehensive AE disclosure to ensure patient safety and data integrity. Similarly, the herbal components of MFI Qingpi, Houpu, and rhubarb pose risks of allergic reactions or GI upset, particularly due to rhubarb’s potent laxative properties, yet the study provides no pharmacokinetic or toxicological data to assess transdermal safety or systemic absorption risks. This omission is critical, given the transdermal delivery method’s potential to alter bioavailability and induce unforeseen side effects.

From a critical perspective, robust AE reporting is essential to build international confidence in TCM. Enhanced transparency, supported by pharmacokinetic studies of herbal components and standardized AE classification (e.g., CTCAE v5.0), would enable precise risk-benefit assessments, facilitating the clinical adoption of integrative therapies while mitigating medico-legal and ethical concerns. To address this, future trials must insist on CTCAE-based classification, prespecified ≥ 30-day monitoring windows, and explicit pharmacokinetic/toxicology data (e.g., via high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry for herbal absorption) or statements of absence with plans for acquisition (e.g., phase I studies within 12 months).

Evaluating the credibility of conclusions in clinical research requires a balanced assessment of evidence strength against potential biases, ensuring that claims are both verifiable through replication and falsifiable under rigorous testing, in line with Popperian principles. Hong et al’s RCT presents promising results[1], including superior GI recovery, improved biomarker profiles (e.g., elevated gastrin, reduced norepinephrine, cortisol, and aldosterone), and enhanced patient outcomes (e.g., clinical efficacy 93.33% vs 75.00%, P = 0.006), which align with 2025 meta-analyses demonstrating TEAS’s efficacy in reducing postoperative GI dysfunction across various surgical contexts. These findings suggest a potential therapeutic advance, particularly in the context of gastroenteroscopy recovery.

However, several methodological limitations compromise the study’s generalizability and robustness. The single-center design, conducted at Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, restricts external validity, potentially overlooking regional variations in TCM practice, patient demographics, or healthcare delivery systems. The unblinded nature of the trial, with deliverers aware of group assignments, introduces performance bias, while the short 3-day follow-up period limits the detection of long-term outcomes, such as sustained GI motility or late-onset complications. These factors, combined with the absence of sham controls, heighten the risk of detection bias, where subjective outcome assessments (e.g., patient satisfaction) may be influenced by expectation effects. The evidence is provisional and of low-to-moderate quality due to the single-center design, short follow-up, and partial blinding, warranting cautious interpretation rather than absolute claims of efficacy.

Verification of these findings necessitates replication in multicenter, double-blinded RCTs with robust sham controls, as demonstrated in a 2024 systematic review[26] of blinding in acupuncture clinical trials, which reported reduced bias and enhanced effect size reliability with proper blinding protocols. Falsifiability could be tested through adequately powered studies yielding null results or subgroup analyses revealing inconsistent treatment effects across diverse populations (e.g., varying Helicobacter pylori status or lesion types). The trial’s assertion of “high efficacy” appears overstated, given these constraints, and risks overstating clinical relevance without acknowledging the need for further validation.

From an analytical standpoint, adopting a Popperian framework emphasizing falsifiable hypotheses and tempered interpretations would bolster TCM’s evidential foundation. Future studies should incorporate long-term follow-ups (e.g., 30-day post-intervention), stratified analyses by comorbidity, and advanced statistical methods (e.g., Bayesian approa

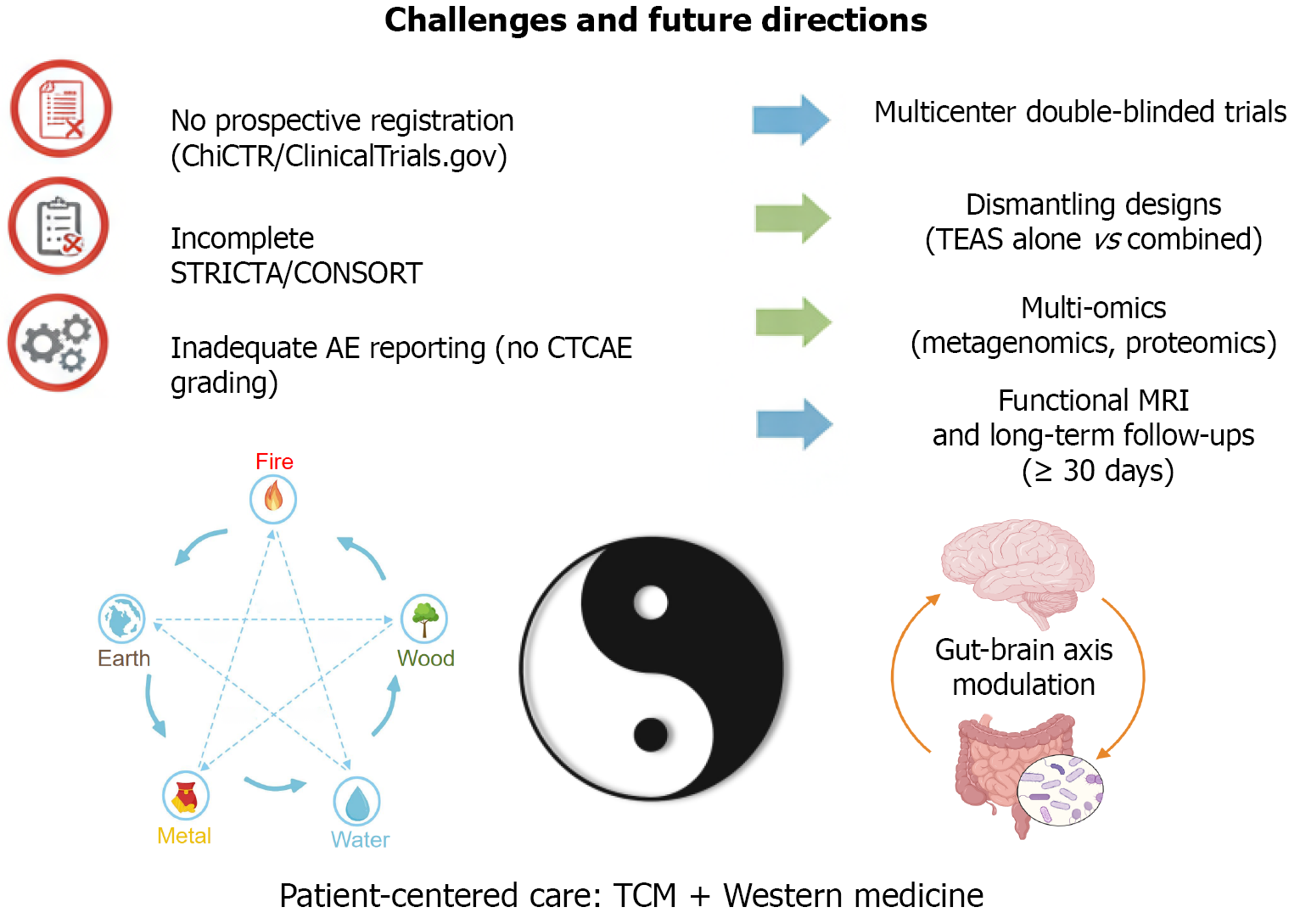

Hong et al’s RCT illuminates the potential of MFI-TEAS to enhance gastroenteroscopy recovery[1], offering a compelling synthesis of TCM wisdom and modern therapeutic strategies. Nevertheless, methodological gaps ranging from inadequate trial registration and STRICTA compliance to insufficient AE monitoring and limited conclusion credibility underscore the need for refinement. By prioritizing prospective registration on platforms like ClinicalTrials.gov, adhering to updated CONSORT and STRICTA guidelines, implementing sham controls and dismantling designs, integrating TCM theory with mechanistic evidence, establishing rigorous AE surveillance with CTCAE grading, and ensuring falsifiable, multicenter-validated conclusions, future research can solidify the evidence base. Figure 1 visually depicts the key methodological challenges, such as lack of prospective registration, incomplete adherence to reporting standards, com

| 1. | Hong X, Wu XY, Xu QL. Application of Meridian flow injection acupoint application combined with transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation in patients undergoing gastroenteroscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:110583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Li Y, Xu X, Chen Y, Li W, Zhang N, Zhang R, Xu E. Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation for the recovery of postoperative gastrointestinal function in patients with colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2025;104:e43699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Huang A, Xiao G, Chen Y, Hu Z, Lee PH, Huang Y, Zhuang Z, Zhang Y, Qing P, Zhao C. Ziwuliuzhu Acupuncture Modulates Clock mRNA, Bmal1 mRNA and Melatonin in Insomnia Rats. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2023;16:109-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Silva S, Singh S, Kashif S, Ogilvie R, Pinto RZ, Hayden JA. Many randomized trials in a large systematic review were not registered and had evidence of selective outcome reporting: a metaepidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2024;176:111568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Xu C, Fan S, Tian Y, Liu F, Furuya-Kanamori L, Clark J, Zhang C, Li S, Lin L, Chu H, Li S, Golder S, Loke Y, Vohra S, Glasziou P, Doi SA, Liu H; VITALITY Collaborative Research Network. Investigating the impact of trial retractions on the healthcare evidence ecosystem (VITALITY Study I): retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2025;389:e082068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Duan Y, Zhao P, Deng Y, Xu Z, Wu S, Shi L, Jiang F, Liu S, Li X, Tang B, Zhou J, Yu L. Incomplete reporting and spin in acupuncture randomised controlled trials: a cross-sectional meta-epidemiological study. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2025;30:259-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | MacPherson H, Altman DG, Hammerschlag R, Youping L, Taixiang W, White A, Moher D; STRICTA Revision Group. Revised STandards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT statement. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 695] [Cited by in RCA: 661] [Article Influence: 41.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li J, Hu JY, Zhai JB, Niu JQ, Kwong JSW, Ge L, Li B, Wang Q, Wang XQ, Wei D, Tian JH, Ma B, Yang KH, Dai M, Tian GH, Shang HC; CENT for TCM Working Group. CONSORT extension for reporting N-of-1 trials for traditional Chinese medicine (CENT for TCM) : Recommendations, explanation and elaboration. Complement Ther Med. 2019;46:180-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yuan H, Wang P, Hu N, Zhang P, Li C, Liu Y, Ma L, Zhu J. A review of the methods used for subjective evaluation of De Qi. J Tradit Chin Med. 2018;38:309-314. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schaible A, Schwan K, Bruckner T, Plaschke K, Büchler MW, Weigand M, Sauer P, Bopp C, Knebel P. Acupuncture to improve tolerance of diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy in patients without systemic sedation: results of a single-center, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial (DRKS00000164). Trials. 2016;17:350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Duan Y, Xu Z, Zhang Y, Liu S, Chen J, Chen Y, Xu N, Tang C, Rong P, Lu L, Wang Y, Lee YS, Kim TH, Riley DS, Shi L, Lee MS, Yu L. CARE extension guideline for acupuncture case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2025;bmjebm-2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wei C, Xu Y, Deng X, Gao S, Wan X, Chen J. Assessment of reporting completeness in acupuncture studies on patients with functional constipation using the STRICTA guidelines. Complement Ther Med. 2022;70:102849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Su XL, Peng CX, Xie YJ. [Discussion on time standards of acupuncture based on Ziwu Liuzhu]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2010;30:574-576. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Chen Y, A S, Liu C, Zhang T, Yang J, Tian X. A Randomized Controlled Trial Assessing the Impact of Transcutaneous Electrical Acupoint Stimulation on Gastrointestinal Motility, Nutritional Status, and Immune Function in Patients Following Cerebrovascular Accident Surgery. J Invest Surg. 2024;37:2434093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li J, Xie J, Guo X, Fu R, Pan Z, Zhao Z. Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation combined with core stability training in postpartum women with diastasis rectus abdominis. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2025;59:101958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jiang T, Li J, Meng L, Wang J, Zhang H, Liu M. Effects of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation on gastrointestinal dysfunction after gastrointestinal surgery: A meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2023;73:102938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yin W, Fang F, Zhang Y, Xi L. Timing of transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation for postoperative recovery in geriatric patients with gastrointestinal tumors: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Front Med (Lausanne). 2025;12:1497647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhang J, Ge X, Zhang K, Qi Y, Ren S, Zhai X. Acupuncture for Parkinson's disease-related constipation: current evidence and perspectives. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1253874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Duanmu CL, Zhang XN, He W, Su YS, Wan HY, Wang Y, Qu ZY, Wang XY, Jing XH. [Electroacupuncture and transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation relieve muscular inflammatory pain by activating afferent nerve fibers in different layers of "Liangqiu"(ST34) in rats]. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2021;46:404-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang S, Zhou S, Han Z, Yu B, Xu Y, Lin Y, Chen Y, Jin Z, Li Y, Cao Q, Xu Y, Zhang Q, Wang YC. From gut to brain: understanding the role of microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1384270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ma K, Wang F, Zhang X, Guo L, Huang Y. Acupuncture and nutritional parallels in obesity: a narrative review of multi-pathway modulation of the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1610814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jang JH, Yeom MJ, Ahn S, Oh JY, Ji S, Kim TH, Park HJ. Acupuncture inhibits neuroinflammation and gut microbial dysbiosis in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:641-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zang Z, Yang F, Qu L, Ge M, Tong L, Xue L, Sun X, Hai Y. Acupuncture modulates the microbiota-gut-brain axis: a new strategy for Parkinson's disease treatment. Front Aging Neurosci. 2025;17:1640389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang Q, Zhang B, Guo Z, Huang J, Niu Y, Huang J, Huang Y, Guo D, Wang B, Feng S. Zhi-zi-chi decoction exerts hypnotic effect through gut-brain axis modulation in insomnia mice. Front Microbiol. 2025;16:1645190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Freites-Martinez A, Santana N, Arias-Santiago S, Viera A. Using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE - Version 5.0) to Evaluate the Severity of Adverse Events of Anticancer Therapies. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2021;112:90-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 569] [Article Influence: 94.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 26. | Liu T, Jiang L, Li S, Cheng S, Zhuang R, Xiong Z, Sun C, Liu B, Zhang H, Yan S. The blinding status and characteristics in acupuncture clinical trials: a systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2024;13:302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/