Published online Jan 14, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i2.114057

Revised: November 3, 2025

Accepted: November 18, 2025

Published online: January 14, 2026

Processing time: 124 Days and 2.8 Hours

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic and treatment-resistant disorder requiring potent therapeutics that are effective and safe. Cedrol (CE) is a bioactive natural product present in many traditional Chinese medicines. It is known for its su

To investigate the therapeutic potential and mechanisms of CE in UC.

The anti-inflammatory activity and intestinal barrier-repairing effects of CE were assessed in a dextran sulfate sodium-induced murine colitis model. Network pharmacology was employed to predict potential targets and pathways. Then mo

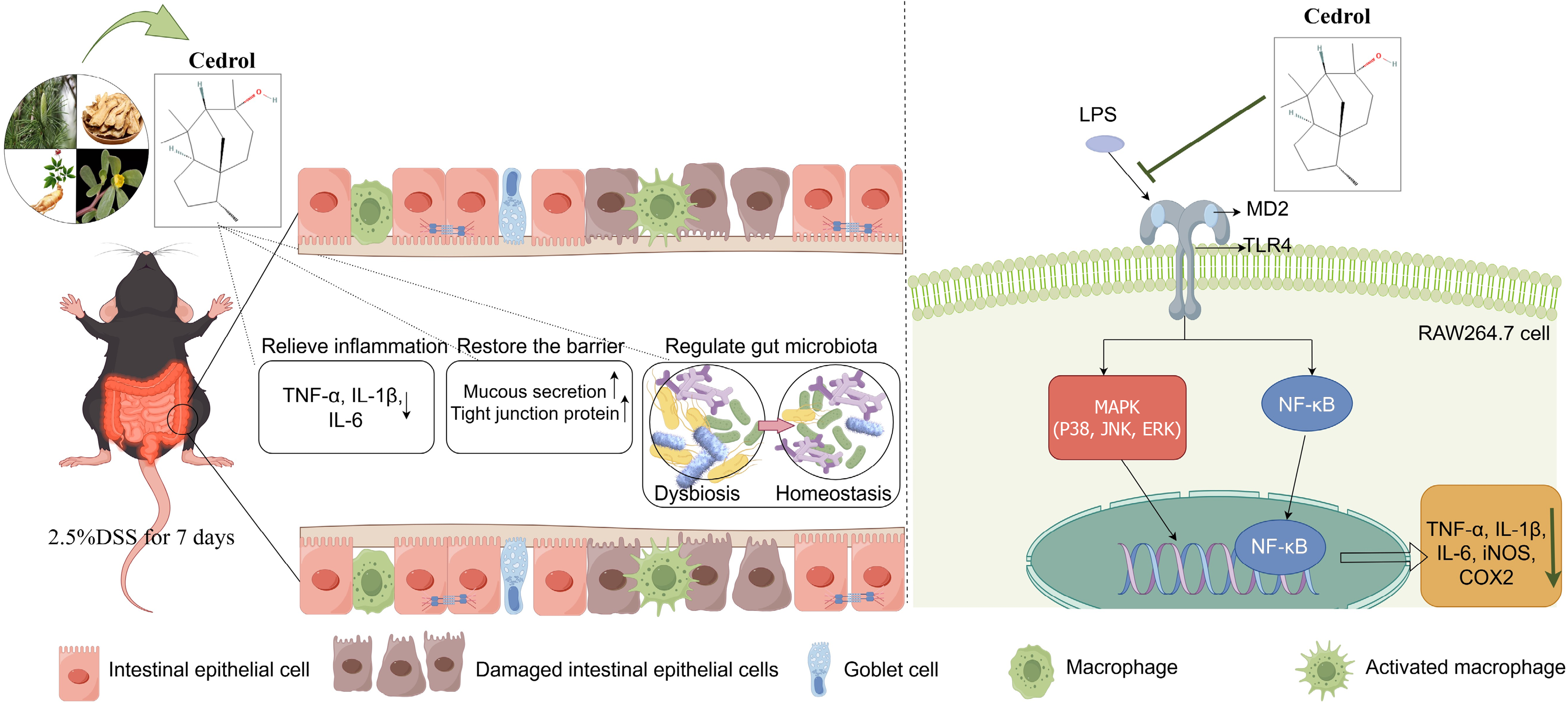

CE significantly alleviated colitis symptoms, mitigated histopathological damage, and suppressed inflammation. Moreover, CE restored intestinal barrier integrity by enhancing mucus secretion and upregulating tight junction proteins (zonula occludens 1, occludin, claudin-1). Mechanistically, CE stably bound to MD2, inhibiting lipopolysaccharide-induced TLR4 signaling in RAW264.7 cells. This led to suppression of the down

CE acted on MD2 to suppress proinflammatory cascades, promoting mucosal barrier reconstitution and microbiota remodeling and supporting its therapeutic use in UC.

Core Tip: Therapeutics to treat ulcerative colitis (UC) must be effective and safe. The natural compound cedrol (CE) possesses anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. However, its therapeutic efficacy and mechanisms in UC remain unclear. We demonstrated that CE ameliorated dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice through multifaceted mechanisms: Attenuating inflammation; Promoting intestinal barrier repair; And restoring gut microbial homeostasis. Mechanistically, CE exerted its anti-inflammatory effects by functionally inhibiting the toll-like receptor 4/myeloid differentiation factor 2 complex, thereby inhibiting the activation of proinflammatory signaling pathways. These findings highlighted the potential of CE as a promising therapeutic agent for UC.

- Citation: Zhao YQ, Zhang Y, Qin Y, Zhang RY, Wang JP. Cedrol ameliorates ulcerative colitis via myeloid differentiation factor 2-mediated inflammation suppression, with barrier restoration and microbiota modulation. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(2): 114057

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i2/114057.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i2.114057

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic, relapsing idiopathic inflammatory condition primarily affecting the colorectum. It is marked by abdominal discomfort, chronic diarrhea, and bloody mucoid stools, leading to significant weight loss and diminishing overall well-being[1,2]. The precise etiology and pathogenesis of UC are elusive although multifactorial origins involving genetic predisposition, environmental factors (diet/Lifestyle), intestinal barrier dysfunction, gut microbiota dysbiosis, and aberrant immune activation are implicated[1,3]. Notably, the incidence of UC has surged globally over recent decades, particularly in Asia. UC is classified by the World Health Organization as a contemporary refractory condition and is often termed “green cancer” due to its persistent, treatment-resistant nature[4]. Current mainstream therapies (aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, biologics, small molecules) yield a clinical remission rate ≤ 60% with frequent adverse effects during prolonged use[1,2,5]. Consequently, developing novel UC therapeutics with enhanced efficacy and long-term safety profiles is imperative.

Natural compounds are a promising source for drug discovery. Phytochemicals including terpenoids, alkaloids, and flavonoids have demonstrated potential for managing UC by functioning through diverse mechanisms such as modu

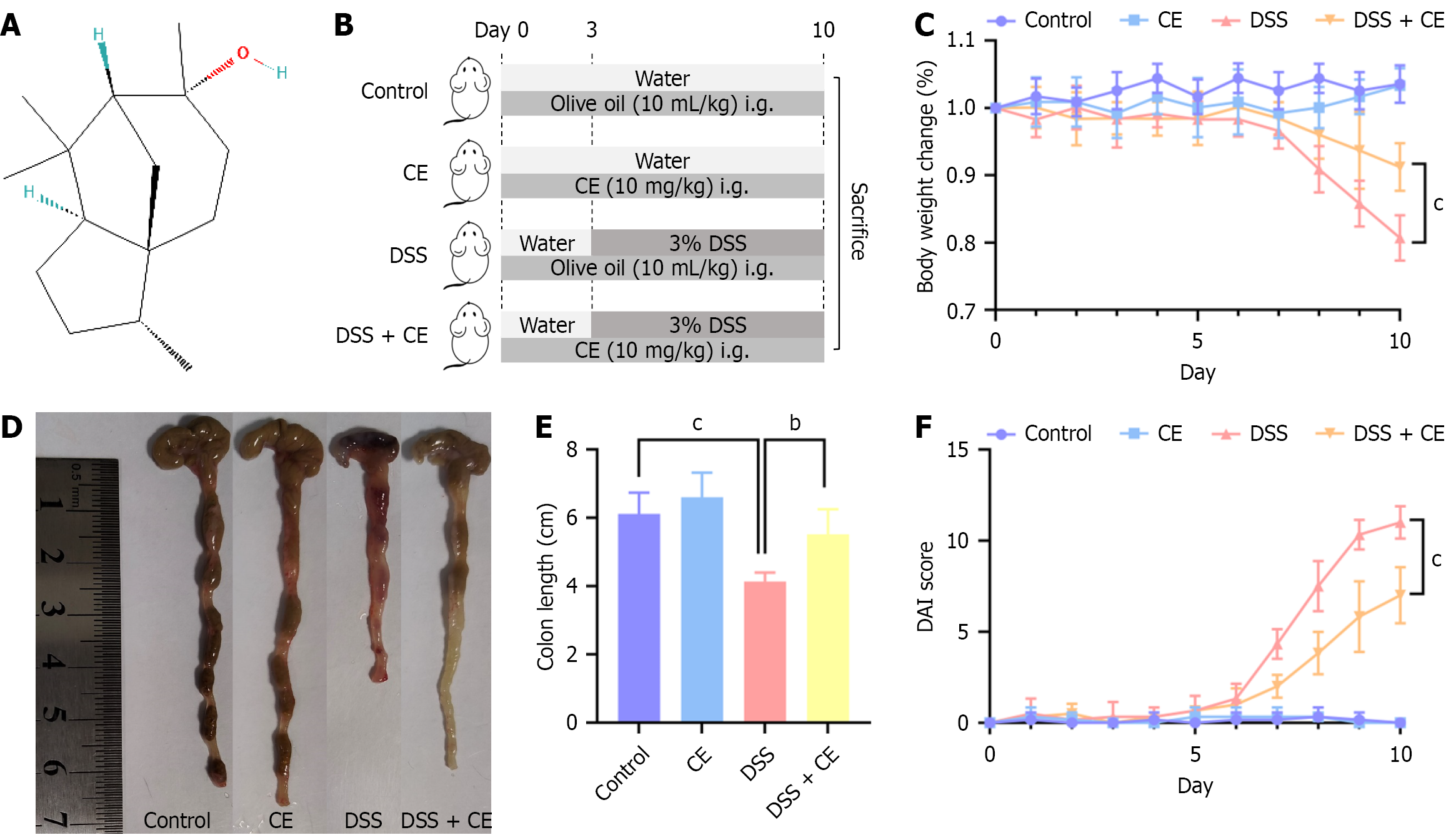

Cedrol (CE, C15H26O; Figure 1A), a natural sesquiterpene alcohol, is widely distributed in nature. It shows notable en

This investigation intended to employ an integrated methodology combining in vivo/in vitro models, network pharmacology, computational simulations (docking/dynamics), and 16S rRNA gene sequencing to evaluate the efficacy and mechanisms of CE, with a focus on inflammatory pathway modulation, intestinal barrier preservation, and microbiome remodeling. It also attempted to explore potential direct pharmacological targets of CE, aiming to provide innovative strategic perspectives for UC intervention.

CE (purity ≥ 98%, C154086) and olive oil (S30503) were sourced from Aladdin Biochemical Technology and Yuanye Bio-Technology (Shanghai, China), respectively. Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) (molecular weight 40 kDa, DCJ1606A) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (L8880) were procured from Seebio Bio-Technology (Shanghai, China) and Solarbio Science and Technology (Beijing, China).

Female C57BL/6 mice (8-week-old, 18-22 g) were procured from Shanxi Provincial People’s Hospital Experimental Animal Center [No. SYXK(Jin)2024-0002] and acclimated for 7 days under specific pathogen-free conditions maintained at 22 ± 1 °C with 55% ± 5% relative humidity and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Animals were randomly assigned to four experimental groups (n = 6): (1) The control group (olive oil 10 mL/kg/day by gavage, days 0-9); (2) The CE group (CE suspension in olive oil 10 mg/kg/day by gavage, days 0-9)[13,14]; (3) The DSS group (olive oil 10 mL/kg/day by gavage, days 0-9 + 2.5% DSS in deionized water ad libitum, days 3-9); and (4) The DSS + CE group (CE suspension in olive oil 10 mg/kg/day by gavage, days 0-9 + 2.5% DSS in deionized water ad libitum, days 3-9) (Figure 1B). The CE suspension was prepared fresh daily in olive oil (final concentration 1 mg/mL).

The disease activity index (DAI) was calculated using standardized criteria (Table 1) derived from daily evaluations of body weight, stool consistency, and rectal bleeding[15,16]. On day 10 cervical dislocation euthanasia preceded colon excision and length measurement. A 1 cm distal segment underwent 4% paraformaldehyde (Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China) fixation, and residual tissue was stored at -80 °C. Experimental protocols received approval from Shanxi Provincial People’s Hospital Ethics Committee [approval No. (2024) 569].

| Score | Weight loss (%) | Stool condition | Bleeding |

| 0 | None | Normal, well-formed | Negative |

| 1 | < 5 | Soft but formed | Occult blood (+) |

| 2 | 5-10 | Soft | Occult blood (++) |

| 3 | 10-20 | Loose | Occult blood (+++) |

| 4 | > 20 | Watery diarrhea | Naked bloody stool |

Distal colon tissues were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by paraffin embedding and sectioning into 3 μm slices. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Servicebio) and alcian blue periodic acid-Schiff (Servicebio) following standard protocols, then examined via optical microscopy (CKX53; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with digital imaging. Histopathological damage was assessed using the criteria outlined in Table 2[17], with the overall score (0-13) representing the sum of individual scores for inflammation extent, crypt damage, ulceration, and edema to ensure a standardized evaluation.

| Score | Inflammation extent | Crypt damage | Ulceration | Edema |

| 0 | None | Intact crypt architecture | No ulcer | Absent |

| 1 | Scattered submucosal cells | Some crypt damage | Small focal ulcers | Present |

| 2 | Focal submucosal infiltrates | Increased crypt spacing, goblet cell loss, crypt shortening | Frequent small ulcers | |

| 3 | Focal submucosal, lamina propria infiltrates | Large crypt-deficient areas amid normal crypts | Extensive surface epithelial loss | |

| 4 | Extensive submucosal, lamina propria, perivascular infiltrates | Crypt absence | ||

| 5 | Transmural inflammation |

Following dewaxing, 3 μm paraffin-embedded tissue sections were subjected to antigen retrieval in preheated Tris-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid buffer (potential of hydrogen = 8.0) at 95 °C for 30 minutes, endogenous peroxidase blocking with 3% hydrogen peroxide (Annjet, Shandong Province, China) (room temperature, 15 minutes in the dark), and nonspecific binding blockade using 3% bovine serum albumin (30 minutes). Primary antibodies (rabbit anti-zonula occludens 1/occludin and mouse anti-claudin-1, 1:500) were incubated with sections overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (diluted 1:200) for 50 minutes. Diaminobenzidine chromogen was freshly prepared for staining, followed by hematoxylin counterstaining (3 minutes) for nuclear visualization. All reagents were sourced from Servicebio unless otherwise noted.

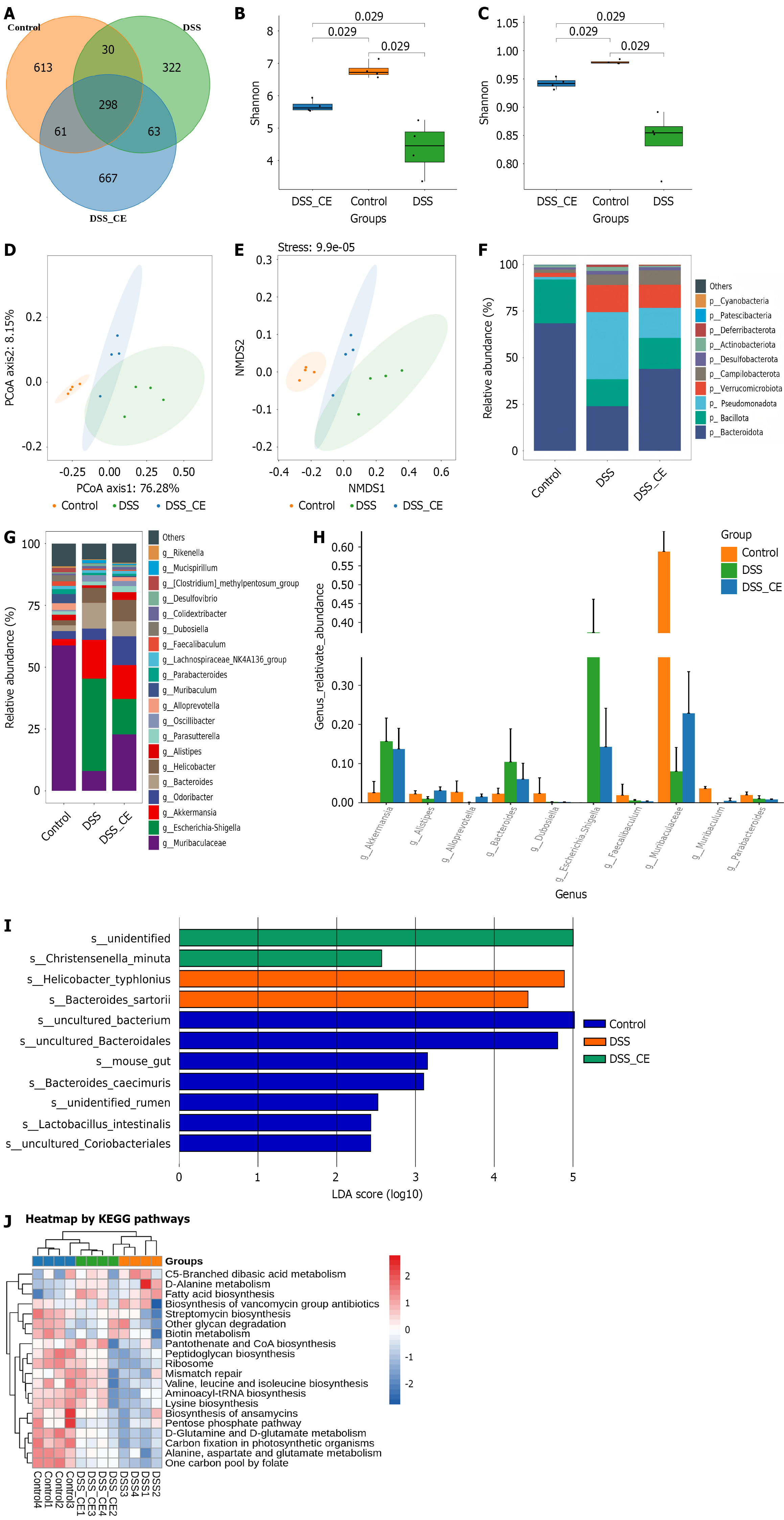

Colon content samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C. Four colon content samples were then randomly selected per group and subjected to genomic DNA extraction using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol for 16S rRNA gene sequencing. DNA was assessed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by quantification employing a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). The V3-V4 hypervariable regions of bacterial 16S rRNA genes were amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and prepared for sequencing using Illumina protocols (San Diego, CA, United States). Finally, paired-end sequencing (2 × 250 bp) was carried out on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Shanghai Wei Huan Biological Technology Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China).

After preprocessing the raw sequence data, we employed DADA2 for comprehensive analysis to produce high-resolution amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). These ASVs were subsequently cross-referenced against the Silva-138-9 reference database to assign accurate taxonomic classifications. Alpha and beta diversity analyses were conducted in QIIME2[18]. Significant differences in microbial community structure between groups were further determined with the Kruskal-Wallis test and the linear discriminant analysis effect size method.

Potential CE targets were identified using SwissTargetPrediction, PharmMapper, and SuperPred databases with gene nomenclature standardization via UniProt. Disease targets of UC were identified via the DisGeNET, GeneCards, and OMIM databases. Common targets were intersected using Venny 2.1.0 and analyzed for protein-protein interactions through the STRING database. The resulting network was constructed and visualized in Cytoscape 3.7.2. Functional enrichment assessments for Gene Ontology terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways were performed using the DAVID database and visualized via the WeiShengXin Cloud Platform.

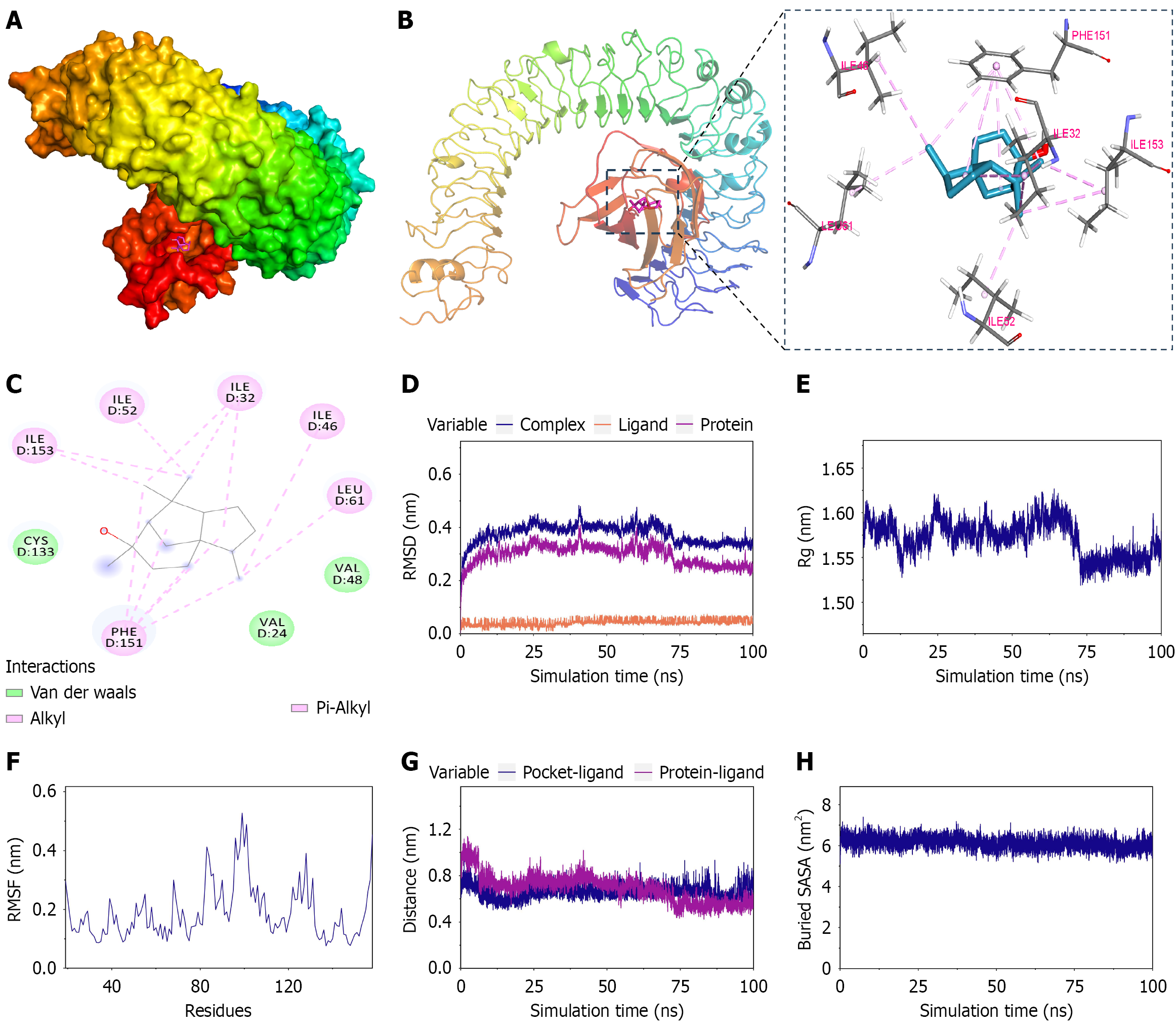

The three-dimensional structure of CE was acquired from PubChem (CID: 65575) and prepared using Chem3D 2020 for molecular docking. The crystal structure of the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/myeloid differentiation factor 2 (MD2) complex (PDB ID: 3FXI) was obtained from the Protein Data Bank. Molecular docking was performed with AutoDock Vina 1.5.7 software. The resulting docking poses were analyzed and visualized using PyMOL 2.6.0.

For the ligand (CE) the general amber force field was applied; for the protein (MD2) the AMBER14SB force field coupled with the TIP3P (transferable interatomic potential with three points model) water model was used. Subsequently, files of MD2 and CE were merged to construct the simulation system of the complex, and molecular dynamic simulations were conducted using the Gromacs 2022. Simulations were run under periodic boundary conditions at 298 K and 1 bar. Hydrogen-bond-related covalent bonds were constrained via LINCS with a 2 fs time step. Electrostatic interactions were computed via Particle Mesh Ewald with a 1.2 nm cutoff. Non-bonded interactions were truncated at 10 Å and updated every ten steps. The system underwent 100 ps of number of particles, volume, and temperature and number of particles, pressure, and temperature equilibration before a 100 ns molecular dynamics simulation. Conformations were saved every 10 ps. Trajectory analysis was performed using VMD and PyMOL.

The RAW264.7 macrophage cell line (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China) was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco, China; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Australia; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% carbon dioxide (HF100; Heal Force Group, Shanghai, China). For experimental treatments cells were plated into 6-well culture dishes (Wuxi NEST Biotechnology, Jiangsu Province, China) and propagated until achieving > 80% confluence. Pretreatment was performed by exposing cells to 20 μmol/L CE for 1 hour, followed by stimulation with 1 μg/mL LPS for 5 hours[13,19]. Finally, cells were collected for subsequent experiments.

Cells were plated into 96-well culture dishes (Wuxi NEST Biotechnology) at a density of 1 × 103 cells/well to 1 × 104 cells/well and cultured overnight. Following exposure to serial CE concentrations for 24 hours, 10 μL cell counting kit-8 reagent (MedChemExpress, Shanghai, China) was added per well and incubated for 30 minutes. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Epoch; BioTek Instruments, Agilent Technologies, Winooski, VT, United States), and cell viability was determined.

Total RNA was extracted with RNAiso Plus (Takara, Kyoto, Japan) and quantified. Then reverse transcribed into complementary DNA with the PrimeScripTM RT reagent Kit (Takara). Real-time quantitative PCR amplification was conducted on a real-time PCR system (CFX96; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States) employing 2x M5 HiPer SYBR Green quantitative PCR SuperMix (Mei5 Biotechnology, Beijing, China). Relative messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels were calculated via the 2-ΔΔCT method. Primers were custom designed and synthesized commercially by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) with sequences detailed in Table 3.

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

| TNF-α | 5’-CCCCAAAGGGATGAGAAGTTC-3’ | 5’-CCTCCACTTGGTGGTTTGCT-3’ |

| IL-1β | 5’-GTTCCCATTAGACAACTGCACTACAG-3’ | 5’-GTCGTTGCTTGGTTCTCCTTGTA-3’ |

| IL-6 | 5’-CCAGAAACCGCTATGAAGTTCC-3’ | 5’-GTTGGGAGTGGTATCCTCTGTGA-3’ |

| β-actin | 5’-GTCAGGTCATCACTATCGGCAAT-3’ | 5’-AGAGGTCTTTACGGATGTCAACGT-3’ |

Protein lysates were extracted using radio immunoprecipitation assay buffer supplemented with 1% phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride and 1% phosphatase inhibitor (Solarbio). Protein quantification was performed by a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples (30 μg/Lane) underwent 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis separation and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Dublin, Ireland). After blocking in 5% skim milk, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies targeting: Phospho-extracellular regulated protein kinase (ERK) 1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204); ERK1/2; Phospho-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (Thr183/Tyr185); JNK; Phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182); P38, phospho-nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) p65 (Ser536); NF-κB p65 (Cell Signaling Technology, Daners, MA, United States); Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2); Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS); Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Proteintech, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China). Secondary antibodies (ABclonal, Woburn, MA, United States) were then applied for 1 hour. The proteins were then subjected to enhanced chemiluminescence (Boster Biological Technology, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China) and visualized with the ChemiDoc X-Ray Spectrometer + Image Lab system (Bio-Rad). The results were analyzed by Image J software (La Jolla, CA, United States).

GraphPad Prism 9.5 was employed for analyses (results presented as mean ± SD). The t-test, one-way analysis of variance, or non-parametric test was applied as appropriate with significance defined as P < 0.05.

To assess the protective potential of CE in UC, a murine colitis model was induced by administering 2.5% DSS in their drinking water for 7 days. Figure 1B presents the experimental scheme. The DSS group lost a significant amount of weight compared with the control group and the CE group. Notably, weight reduction in the DSS + CE group was considerably attenuated compared with the DSS group (Figure 1C). The colon length was markedly reduced in the DSS group compared with the control and CE groups. However, CE treatment substantially mitigated DSS-induced colon shortening (Figure 1D and E). Similarly, DAI scores increased significantly in the DSS group while declining markedly in the DSS + CE group (Figure 1F), indicating attenuation of colitis severity following CE administration.

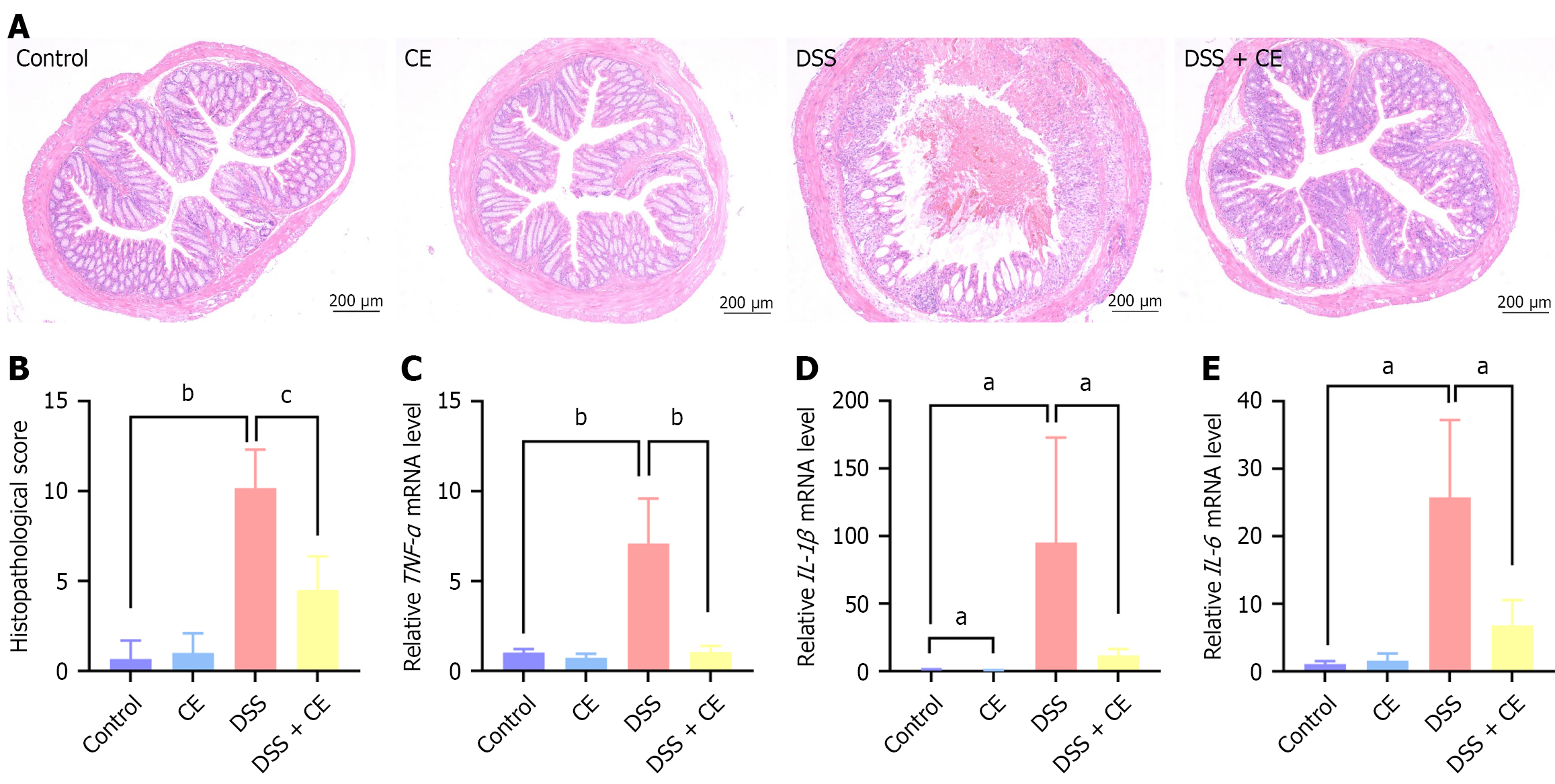

Histopathological damage was further assessed using hematoxylin and eosin staining. The DSS group displayed inflammatory cell infiltration, mucosal damage, crypt atrophy, and edema in colonic sections (Figure 2A). In contrast the DSS + CE group showed marked attenuation of the aforementioned pathological features. Additionally, the histopathological score was significantly elevated in the DSS group while it was reduced in the DSS + CE group (Figure 2B). These observations demonstrated that CE attenuated colonic injury in colitis. Following this, the anti-inflammatory capacity of CE was assessed. Proinflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6 were markedly increased in the colonic tissues of the DSS group. CE administration effectively suppressed this DSS-induced upregulation (Figure 2C-E).

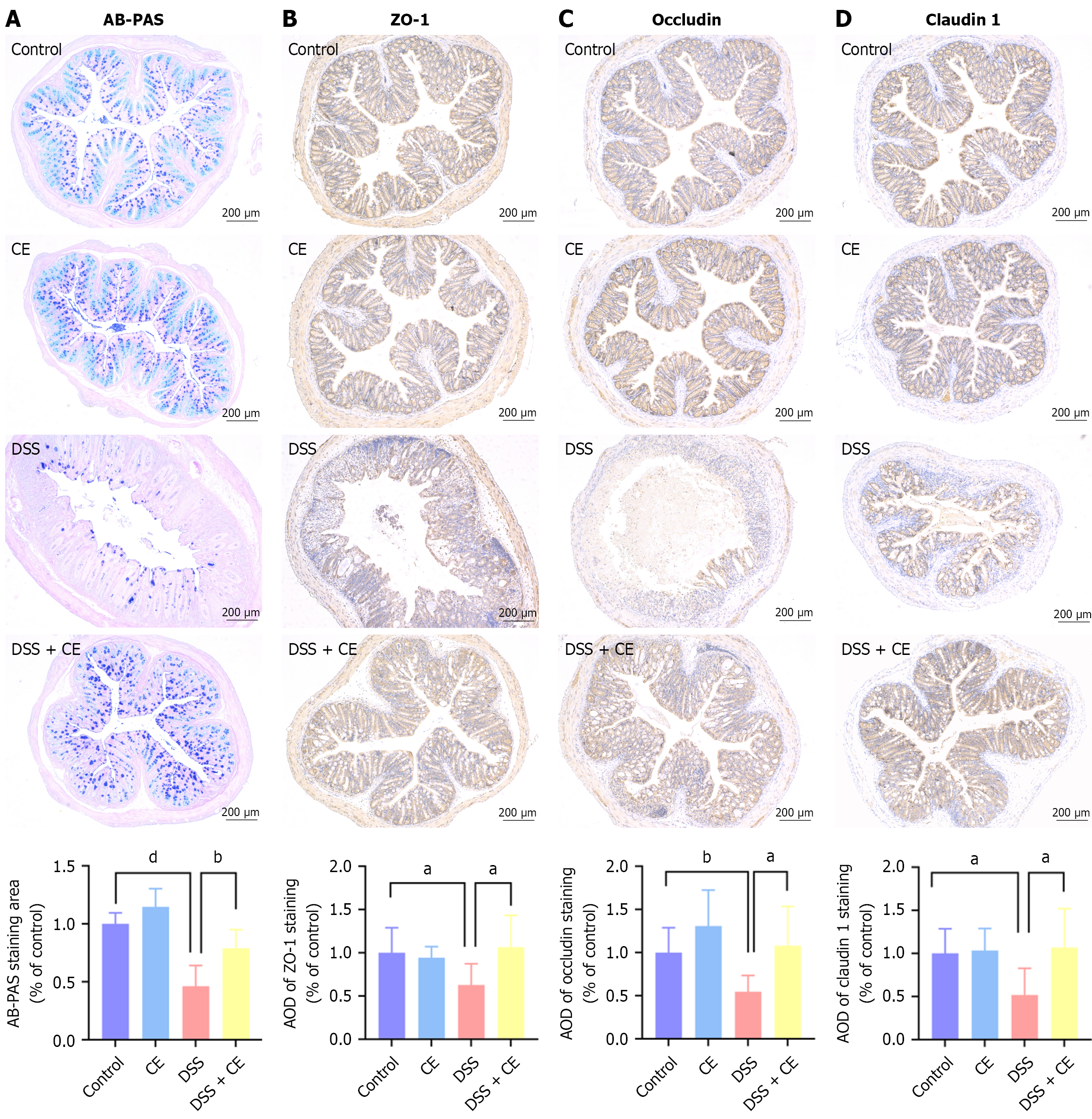

To investigate the ameliorative effects of CE on gut barrier integrity in DSS-induced colitis, goblet cell mucin production was determined via alcian blue periodic acid-Schiff staining. TJ protein (zonula occludens 1, occludin, claudin-1) expression was examined through immunohistochemistry. DSS exposure significantly reduced mucus secretion and downregulated TJ protein expression compared with the control group (Figure 3). CE treatment reversed these alterations, increasing both mucus production and TJ protein expression. These results demonstrated that CE ameliorated intestinal barrier dysfunction in DSS-induced colitis.

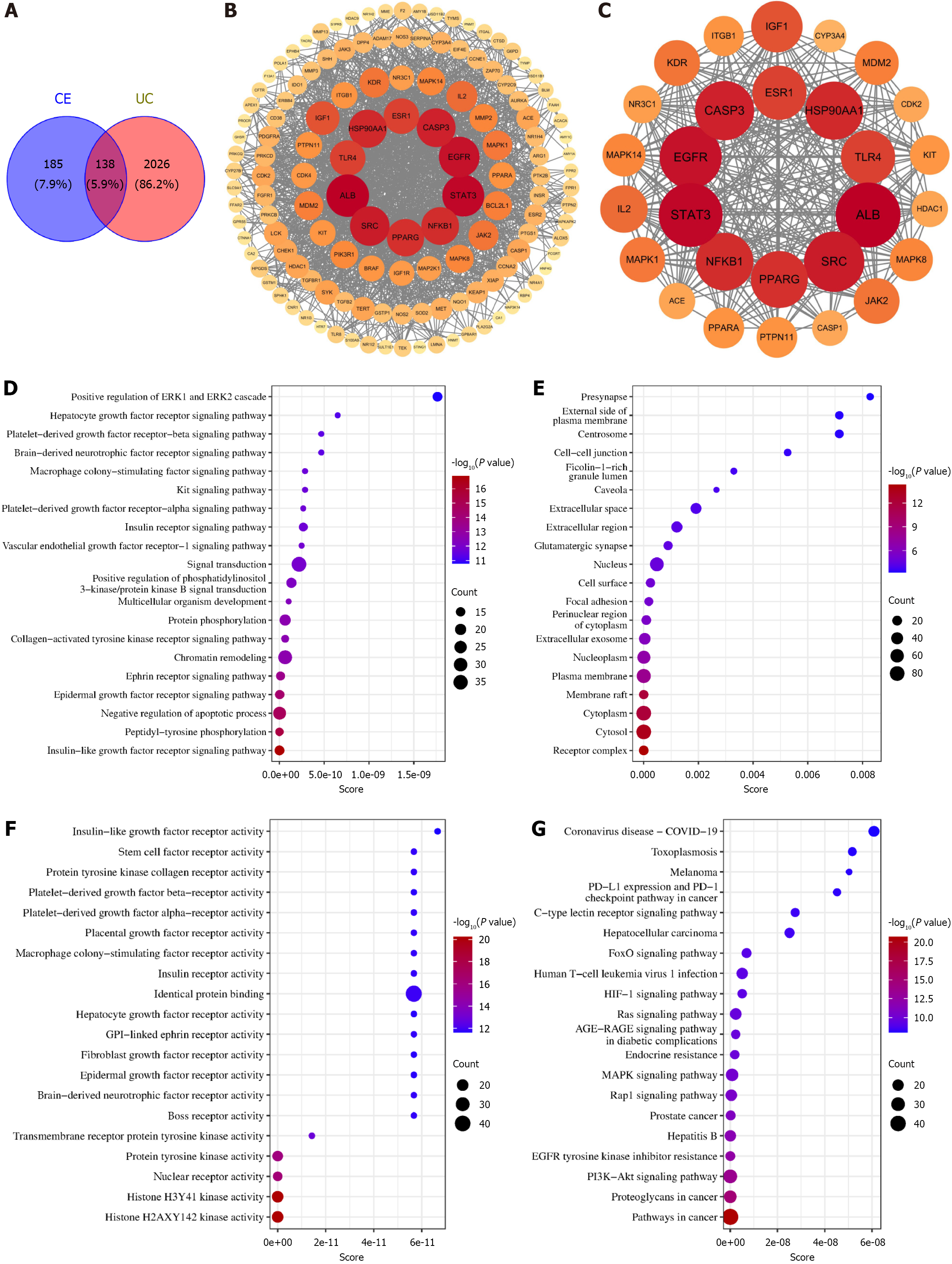

To elucidate the potential mechanisms of CE against UC, the network pharmacology analysis identified 323 CE-related targets and 2164 UC-associated targets, yielding 138 overlapping therapeutic targets (Figure 4A). Protein-protein interaction analysis of these targets revealed a network comprising 138 nodes and 1527 edges (Figure 4B) with subsequent screening identifying 28 core targets including ALB, STAT3, EGFR, SRC, CASP3, HSP90AA1, NFKB1, PPARG, ESR1, and TLR4 (Figure 4C). Functional enrichment analysis identified the following: Biological processes (109 terms) primarily encompassing negative regulation of apoptosis, protein phosphorylation, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) signaling activation, and signal transduction (Figure 4D); Cellular components (21 terms) predominantly involving receptor complexes, cytosol, and cytoplasm (Figure 4E); Molecular functions (54 terms) principally associated with histone H3-Y41/H2A-X142-targeted and tyrosine protein kinase activities (Figure 4F). KEGG-based analysis identified 123 significantly enriched pathways (top 20 shown in Figure 4G) with PI3K-AKT, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and FoxO signaling pathways demonstrating particular relevance to UC pathogenesis.

Numerous preclinical investigations have demonstrated that TLR4-mediated signaling pathways are central to the pathophysiology of UC, positioning this receptor as a promising therapeutic target[20-22]. TLR4 assembles with MD2 on the cell surface to form a functional complex that recognizes pathogen-associated ligands like LPS to initiate downstream inflammatory signaling. Based on the prediction from network pharmacology, we first utilized molecular docking to explore the potential interaction between CE and the TLR4/MD2 complex. The docking analysis revealed CE binding within MD2 through Van der Waals interactions with CYS133, VAL24, and VAL48 in addition to hydrophobic contacts (alkyl/π-alkyl) with ILE153, ILE52, ILE32, ILE46, LEU61, and PHE151 (Figure 5A-C). The calculated binding affinity of -6.7 kcal/mol suggested favorable binding.

Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed complex stability via convergent root mean square deviation values indicating structural equilibrium, consistent radius of gyration reflecting structural compactness, residue-specific fluctuation profiles from root mean square fluctuation analysis, stable ligand-pocket distances in centroid evolution, and persistent molecular interfaces demonstrated by equilibrated buried solvent accessible surface area (Figure 5D-H). These computational analyses substantiated direct and stable binding between CE and MD2.

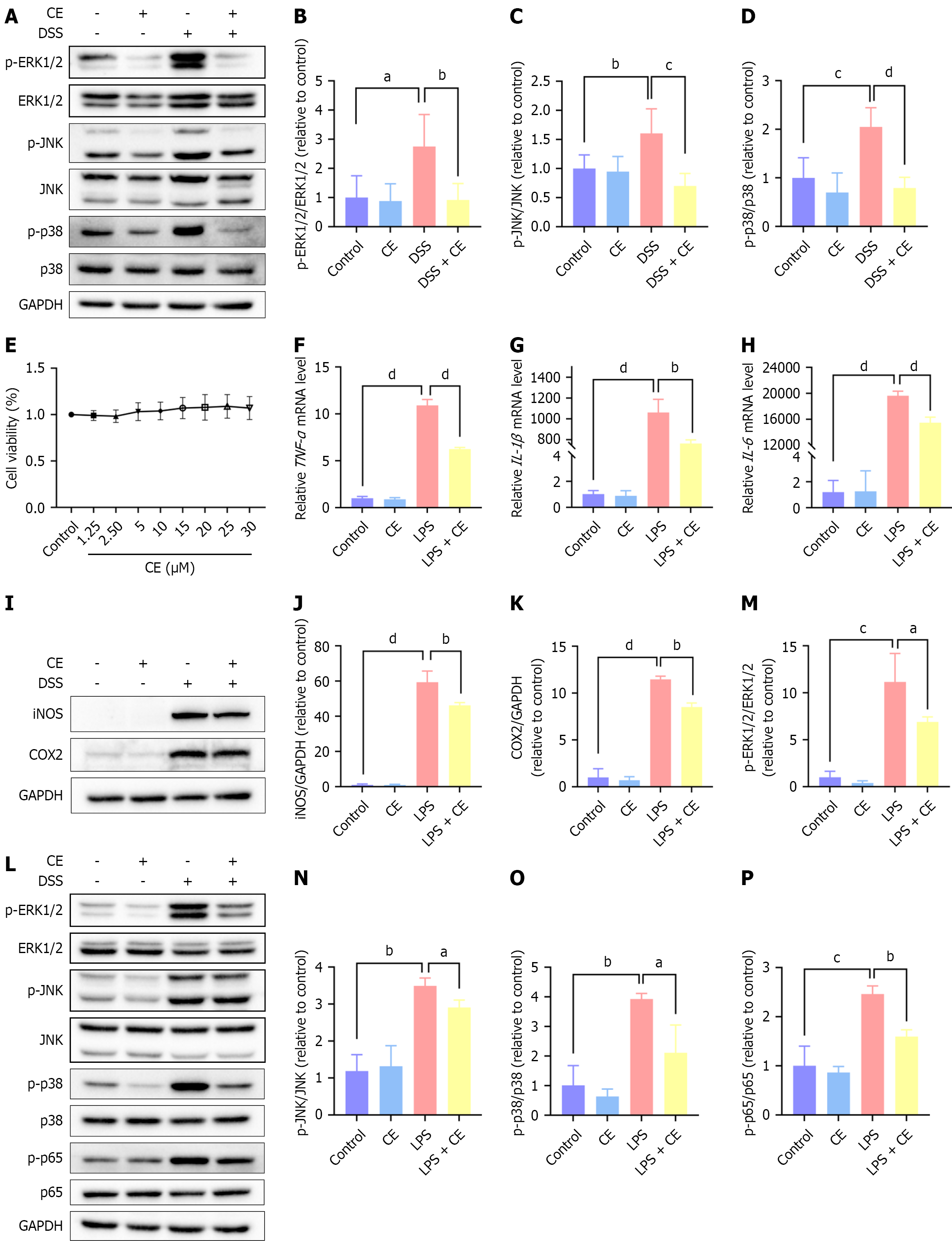

When TLR4 forms a complex with MD2 (its coreceptor), the complex recognizes LPS and initiates downstream activation of the MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways, culminating in a proinflammatory cascade[23]. To demonstrate this in our model, we utilized western blot analysis to measure phosphorylated and total ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 levels in mouse colon tissues. The phosphorylation ratios of ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 were significantly increased in the DSS group. CE treatment significantly reverted the phosphorylation status toward baseline (Figure 6A-D).

To further explore the potential role of CE in TLR4/MD2-mediated inflammatory signaling, we conducted in vitro experiments in RAW264.7 cells. The cell counting kit-8 assay confirmed that CE (0-30 μM) exerted no cytotoxicity on RAW264.7 cells (Figure 6E). Based on prior studies[13,19], 20 μM of CE was selected for subsequent experiments. LPS (1 μg/mL, 5 hours; a canonical TLR4 activator) sharply elevated TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 mRNA levels and upregulated iNOS and COX-2 protein expression in RAW264.7 cells. Notably, pretreatment with CE (20 μM) substantially attenuated these inflammatory markers (Figure 6F-K). CE pretreatment markedly suppressed the LPS-induced phosphorylation of MAPK family members (ERK1/2, JNK, p38) and the RelA subunit (NF-κB p65) (Figure 6L-P).

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that CE’s anti-inflammatory effects are mediated through suppression of TLR4/MD2-dependent MAPK and NF-κB pathway activation. Importantly, quantification of TLR4 protein expression revealed no significant differences across experimental groups (Supplementary Figure 1), indicating that CE’s mechanism involves functional inhibition of the TLR4/MD2 complex rather than reduced receptor expression.

Cumulative evidence suggests that there is a robust correlation linking intestinal microbiome dysbiosis to UC patho

Phylum-level analysis revealed a marked reduction in Bacteroidota and Bacillota and elevation of Pseudomonadota in the DSS group. CE administration partially reversed these perturbations (Figure 7F). Genus-level analysis further indicated elevated Escherichia-Shigella, and Akkermansia and reduced Muribaculaceae in the DSS group. CE treatment partially counteracted these shifts (Figure 7G). Specifically, CE significantly increased beneficial genera (Muribaculaceae, Muribaculum, Alistipes, Alloprevotella) while suppressing taxa (Akkermansia, Bacteroides, Escherichia-Shigella) that were increased in the DSS group (P < 0.05) (Figure 7H). Linear discriminant analysis (> 2) identified Christensenella minuta as a key discriminative species in the DSS + CE group (Figure 7I). Finally, KEGG functional prediction suggested the potential involvement of CE in key metabolic pathways (pantothenate/CoA, peptidoglycan, branched-chain amino acid, lysine, and aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis) and cellular processes (ribosome and mismatch repair) (Figure 7J).

UC is a chronic, recurrent, and cancer-prone inflammatory bowel disease. Current treatment strategies are unsatisfactory, and there is an urgent need to develop safer and more effective therapies. Natural compounds are valuable sources for drug discovery due to their diverse chemical structures and potential therapeutic benefits[1,2,5]. CE is a natural compound that exists in various medicinal herbs and possesses anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties[8-11]. However, its efficacy and mechanisms in UC have not been thoroughly investigated. This study examined the therapeutic effects and mechanistic basis of CE in experimental models of UC to provide novel insights into future intervention strategies.

We utilized the extensively validated DSS-induced colitis murine model to faithfully recapitulate the hallmark clinical manifestations of UC including body weight decline, hematochezia, higher DAI values, shortened colon length, and histopathological findings (e.g., crypt loss, neutrophil infiltration). Notably, CE administration significantly ameliorated disease phenotypes and concomitantly attenuated histopathological damage and downregulated the production of key proinflammatory cytokines in colonic tissues. This finding was consistent with the anti-inflammatory properties of CE on arthritis[8,9,19].

CE also enhanced the expression of TJ proteins and stimulated mucus production by goblet cells, leading to restored gut barrier function. Unlike corticosteroids, which often exacerbate mucosal fragility and increase relapse rates despite their anti-inflammatory efficacy[25], CE exhibited superior therapeutic potential by concurrently suppressing inflammatory responses and restoring intestinal barrier integrity, resulting in a comprehensive and safe clinical profile. Analogous mechanisms have been documented in other natural products and bioactive constituents of traditional Chinese medicine[26], such as berberine[27,28] and curcumin[29].

To build upon these findings, network pharmacology analysis predicted that the therapeutic efficacy of CE in UC may be mediated through the PI3K-AKT, MAPK, and FoxO signaling pathways while simultaneously identifying 28 core molecular targets including pivotal regulators such as STAT3, NFKB1, and TLR4. The MAPK signaling cascade is a well-established inflammatory pathway implicated in UC pathogenesis. Extensive prior research confirmed that pharmacological inhibition of this cascade effectively ameliorated UC inflammatory responses[30,31]. Our investigation confirmed that CE intervention significantly suppressed phosphorylation of critical MAPK signaling molecules such as ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 within the colonic tissues of the DSS-induced colitis murine model. This observation aligned with estab

TLR4 is a critical pattern recognition receptor residing on the cell membrane. It has the capacity to trigger downstream signaling primarily through the MAPK and NF-κB pathways. This signaling cascade potently amplifies the inflammatory response, ultimately leading to damage within the mucosal lining. Consequently, this receptor serves as a critical mediator in the initiation and progression of UC[20,32]. Targeting the TLR4 pathway is a promising therapeutic strategy for UC. Preclinical studies indicate that many plant-derived compounds (phytochemicals) effectively modulate TLR4 signaling. This activity has been observed in diverse experimental systems including animal models of colitis and in vitro cell culture, highlighting the potential to ameliorate intestinal inflammation[33-35].

MD2 is a secreted glycoprotein that associates with the extracellular domain of TLR4. This coreceptor directly binds bacterial LPS and is essential for facilitating the dimerization of TLR4, leading to the activation of downstream inflammatory signaling pathways[36]. Building upon the network pharmacology analysis in this study that identified TLR4 as a core therapeutic target, we subsequently employed molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations to investigate its potential interaction with CE. Computational analyses revealed that CE exhibited high-affinity binding (docking energy: -6.7 kcal/mol) to MD2. Furthermore, extended molecular dynamics simulations demonstrated stable binding as evidenced by root mean square deviation, radius of gyration, root mean square fluctuation, centroid evolution, and buried solvent accessible surface area. To complement these computational findings, subsequent cell-based experiments demonstrated that CE markedly inhibited LPS-triggered activation of the MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Critically, we confirmed that CE achieved this suppression without altering total TLR4 protein levels, indicating functional inhibition rather than receptor downregulation. The collective evidence supports the hypothesis that CE exerts its anti-inflammatory activity by directly binding to MD2 and subsequently suppressing activation of the downstream MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways of TLR4.

To investigate the influence of CE on gut microbiota homeostasis, we conducted a detailed assessment of the intestinal microbiota composition. The results demonstrated that the DSS group exhibited a pronounced decline in α-diversity indices and disruptions of the microbial community architecture relative to controls. Specifically, we detected a decline in the abundance of Bacteroidota and Bacillota accompanied by an expansion of the potentially pathogenic phylum Pseudomonadota, particularly Escherichia-Shigella. These dysbiotic changes were consistent with established findings in colitis models[37,38]. CE administration effectively countered these deleterious shifts. Treatment with CE restored gut microbiota α-diversity and richness and promoted a compositional shift towards a more beneficial profile. We observed selective enrichment of putatively beneficial taxa, including Muribaculaceae, Muribaculum, Alistipes, and Alloprevotella, while simultaneously suppressing the proliferation of taxa such as Akkermansia, Bacteroides, and Escherichia-Shigella that were elevated in the pathological state induced by DSS. A particularly intriguing finding emerged from the linear discriminant analysis that highlighted Christensenella minuta as a key discriminant feature significantly associated with the CE treatment group. Christensenella minuta DSM 22607 produces substantial amounts of acetic acid and fair quantities of butyric acid. These microbially derived short-chain fatty acids are known to dampen inflammation via suppression of the NF-κB pathway and to enhance mucosal healing in a mouse colitis model[39]. Consequently, Christensenella minuta is a viable candidate for microbiome-targeted therapeutic strategies in inflammatory bowel disease[40].

A key finding of this study is that CE concurrently targets multiple interconnected components of UC pathophysio

Our study provided the first evidence that CE exerts notable therapeutic effects against DSS-induced colitis through a coordinated multi-mechanistic action, including anti-inflammatory activity via functional suppression of the TLR4/MD2-MAPK/NF-κB axis, restoration of intestinal barrier integrity, and amelioration of gut microbiota dysbiosis. Beyond the current findings, several important questions remain for future investigation. While our data strongly suggest TLR4/MD2 as a functional target, definitive confirmation will require more direct interventions, such as TLR4-neutralizing antibodies, TLR4-knockout models, or TLR4-overexpression systems. Furthermore, given the central role of immune dysregulation in UC, the impact of CE on specific immune cell populations represents a critical avenue for future research. Subsequent studies should systematically evaluate the compound’s influence on the functional polarization of macrophages (e.g., M1/M2), the differentiation of T helper (Th) cell subsets (e.g., Th1, Th2, Th17, and regulatory T cell), and the activity of dendritic cells. Elucidating these immunomodulatory effects will be essential to efforts that will fully uncover the mechanism by which CE restores immune homeostasis in the colonic microenvironment.

These robust preclinical outcomes position CE as a promising translational candidate for UC. However, it is important to acknowledge that the current investigation employed a single dosage without a comprehensive dose-response assessment. Future studies should include detailed pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses, chronic toxicity evaluation, and validation in clinically relevant animal models to confirm the efficacy and safety profile of CE prior to advancing to clinical translation.

CE ameliorated DSS-induced colitis through three complementary mechanisms: (1) Attenuating inflammation via TLR4/MD2-mediated suppression of MAPK and NF-κB signaling; (2) Restoring intestinal barrier function; and (3) Modulating the gut microbiota (Figure 8). These multifaceted actions demonstrated that CE is a promising natural therapeutic candidate for UC.

| 1. | Le Berre C, Honap S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2023;402:571-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 938] [Reference Citation Analysis (104)] |

| 2. | Wangchuk P, Yeshi K, Loukas A. Ulcerative colitis: clinical biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and emerging treatments. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2024;45:892-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kałużna A, Olczyk P, Komosińska-Vassev K. The Role of Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells in the Pathogenesis and Development of the Inflammatory Response in Ulcerative Colitis. J Clin Med. 2022;11:400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhang Y, Chu X, Wang L, Yang H. Global patterns in the epidemiology, cancer risk, and surgical implications of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2024;12:goae053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abbas A, Di Fonzo DMP, Wetwittayakhlang P, Al-Jabri R, Lakatos PL, Bessissow T. Management of ulcerative colitis: where are we at and where are we heading? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;18:567-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Huang Y, Wu Q, Li S, Lin X, Yang S, Zhu R, Fu C, Zhang Z. Harnessing nature's pharmacy: investigating natural compounds as novel therapeutics for ulcerative colitis. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1394124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen B, Dong X, Zhang JL, Sun X, Zhou L, Zhao K, Deng H, Sun Z. Natural compounds target programmed cell death (PCD) signaling mechanism to treat ulcerative colitis: a review. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1333657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang YM, Shen J, Zhao JM, Guan J, Wei XR, Miao DY, Li W, Xie YC, Zhao YQ. Cedrol from Ginger Ameliorates Rheumatoid Arthritis via Reducing Inflammation and Selectively Inhibiting JAK3 Phosphorylation. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69:5332-5343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang Y, Liu Y, Peng F, Wei X, Hao H, Li W, Zhao Y. Cedrol from ginger alleviates rheumatoid arthritis through dynamic regulation of intestinal microenvironment. Food Funct. 2022;13:11825-11839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bi Y, Xie Z, Cao X, Ni H, Xia S, Bao X, Huang Q, Xu Y, Zhang Q. Cedrol attenuates acute ischemic injury through inhibition of microglia-associated neuroinflammation via ERβ-NF-κB signaling pathways. Brain Res Bull. 2024;218:111102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chang KF, Liu CY, Huang YC, Hsiao CY, Tsai NM. Downregulation of VEGFR2 signaling by cedrol abrogates VEGF‑driven angiogenesis and proliferation of glioblastoma cells through AKT/P70S6K and MAPK/ERK1/2 pathways. Oncol Lett. 2023;26:342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xu MR, Lin CH, Wang CH, Wang SY. Investigate the metabolic changes in intestinal diseases by employing a (1)H-NMR-based metabolomics approach on Caco-2 cells treated with cedrol. Biofactors. 2025;51:e2132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xu C, Jin SQ, Jin C, Dai ZH, Wu YH, He GL, Ma HW, Xu CY, Fang WL. Cedrol, a Ginger-derived sesquiterpineol, suppresses estrogen-deficient osteoporosis by intervening NFATc1 and reactive oxygen species. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;117:109893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Forouzanfar F, Pourbagher-Shahri AM, Ghazavi H. Evaluation of Antiarthritic and Antinociceptive Effects of Cedrol in a Rat Model of Arthritis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:4943965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim JJ, Shajib MS, Manocha MM, Khan WI. Investigating intestinal inflammation in DSS-induced model of IBD. J Vis Exp. 2012;3678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Wirtz S, Popp V, Kindermann M, Gerlach K, Weigmann B, Fichtner-Feigl S, Neurath MF. Chemically induced mouse models of acute and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nat Protoc. 2017;12:1295-1309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 538] [Cited by in RCA: 1150] [Article Influence: 127.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Stillie R, Stadnyk AW. Role of TNF receptors, TNFR1 and TNFR2, in dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1515-1525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, Alexander H, Alm EJ, Arumugam M, Asnicar F, Bai Y, Bisanz JE, Bittinger K, Brejnrod A, Brislawn CJ, Brown CT, Callahan BJ, Caraballo-Rodríguez AM, Chase J, Cope EK, Da Silva R, Diener C, Dorrestein PC, Douglas GM, Durall DM, Duvallet C, Edwardson CF, Ernst M, Estaki M, Fouquier J, Gauglitz JM, Gibbons SM, Gibson DL, Gonzalez A, Gorlick K, Guo J, Hillmann B, Holmes S, Holste H, Huttenhower C, Huttley GA, Janssen S, Jarmusch AK, Jiang L, Kaehler BD, Kang KB, Keefe CR, Keim P, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koester I, Kosciolek T, Kreps J, Langille MGI, Lee J, Ley R, Liu YX, Loftfield E, Lozupone C, Maher M, Marotz C, Martin BD, McDonald D, McIver LJ, Melnik AV, Metcalf JL, Morgan SC, Morton JT, Naimey AT, Navas-Molina JA, Nothias LF, Orchanian SB, Pearson T, Peoples SL, Petras D, Preuss ML, Pruesse E, Rasmussen LB, Rivers A, Robeson MS 2nd, Rosenthal P, Segata N, Shaffer M, Shiffer A, Sinha R, Song SJ, Spear JR, Swafford AD, Thompson LR, Torres PJ, Trinh P, Tripathi A, Turnbaugh PJ, Ul-Hasan S, van der Hooft JJJ, Vargas F, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Vogtmann E, von Hippel M, Walters W, Wan Y, Wang M, Warren J, Weber KC, Williamson CHD, Willis AD, Xu ZZ, Zaneveld JR, Zhang Y, Zhu Q, Knight R, Caporaso JG. Author Correction: Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 66.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen X, Shen J, Zhao JM, Guan J, Li W, Xie QM, Zhao YQ. Cedrol attenuates collagen-induced arthritis in mice and modulates the inflammatory response in LPS-mediated fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Food Funct. 2020;11:4752-4764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lu Y, Li X, Liu S, Zhang Y, Zhang D. Toll-like Receptors and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Immunol. 2018;9:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 32.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tam JSY, Coller JK, Hughes PA, Prestidge CA, Bowen JM. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) antagonists as potential therapeutics for intestinal inflammation. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2021;40:5-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mao N, Yu Y, Lu X, Yang Y, Liu Z, Wang D. Preventive effects of matrine on LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 cells and intestinal damage in mice through the TLR4/NF-κB/MAPK pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;143:113432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhou L, Yang T, Zhang S, Liu D, Feng C, Ni J, Shi Q, Liu Y, Meng Y, Zhu Y, Tang H, Wang J, Ma A. Targeting myeloid differentiation protein 2 ameliorates rheumatoid arthritis by inhibiting inflammation and ferroptosis via MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways. J Mol Med (Berl). 2025;103:821-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Guo XY, Liu XJ, Hao JY. Gut microbiota in ulcerative colitis: insights on pathogenesis and treatment. J Dig Dis. 2020;21:147-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Salice M, Rizzello F, Calabrese C, Calandrini L, Gionchetti P. A current overview of corticosteroid use in active ulcerative colitis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:557-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gupta M, Mishra V, Gulati M, Kapoor B, Kaur A, Gupta R, Tambuwala MM. Natural compounds as safe therapeutic options for ulcerative colitis. Inflammopharmacology. 2022;30:397-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Liu C, Gong Q, Liu W, Zhao Y, Yan X, Yang T. Berberine-loaded PLGA nanoparticles alleviate ulcerative colitis by targeting IL-6/IL-6R axis. J Transl Med. 2024;22:963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yang T, Qin N, Liu F, Zhao Y, Liu W, Fan D. Berberine regulates intestinal microbiome and metabolism homeostasis to treat ulcerative colitis. Life Sci. 2024;338:122385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Karthikeyan A, Young KN, Moniruzzaman M, Beyene AM, Do K, Kalaiselvi S, Min T. Curcumin and Its Modified Formulations on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): The Story So Far and Future Outlook. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zheng S, Xue T, Wang B, Guo H, Liu Q. Chinese Medicine in the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis: The Mechanisms of Signaling Pathway Regulations. Am J Chin Med. 2022;50:1781-1798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zang R, Liu Z, Wu H, Chen W, Zhou R, Yu F, Li Y, Xu H. Candida utilis Ameliorates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis in Mice via NF-κB/MAPK Suppression and Gut Microbiota Modulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:1993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Candelli M, Franza L, Pignataro G, Ojetti V, Covino M, Piccioni A, Gasbarrini A, Franceschi F. Interaction between Lipopolysaccharide and Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:6242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 53.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Dai W, Long L, Wang X, Li S, Xu H. Phytochemicals targeting Toll-like receptors 4 (TLR4) in inflammatory bowel disease. Chin Med. 2022;17:53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lv K, Song J, Wang J, Zhao W, Yang F, Feiya J, Bai L, Guan W, Liu J, Ho CT, Li S, Zhao H, Wang Z. Pterostilbene Alleviates Dextran Sodium Sulfate (DSS)-Induced Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction Involving Suppression of a S100A8-TLR-4-NF-κB Signaling Cascade. J Agric Food Chem. 2024;72:18489-18496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wei FH, Xie WY, Zhao PS, Gao W, Gao F. Echinacea purpurea Polysaccharide Ameliorates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis by Restoring the Intestinal Microbiota and Inhibiting the TLR4-NF-κB Axis. Nutrients. 2024;16:1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sun M, Zhan H, Long X, Alsayed AM, Wang Z, Meng F, Wang G, Mao J, Liao Z, Chen M. Dehydrocostus lactone alleviates irinotecan-induced intestinal mucositis by blocking TLR4/MD2 complex formation. Phytomedicine. 2024;128:155371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lao J, Chen M, Yan S, Gong H, Wen Z, Yong Y, Jia D, Lv S, Zou W, Li J, Tan H, Yin H, Kong X, Liu Z, Guo F, Ju X, Li Y. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus G7 alleviates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis by regulating the intestinal microbiota. BMC Microbiol. 2025;25:168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | He XX, Li YH, Yan PG, Meng XC, Chen CY, Li KM, Li JN. Relationship between clinical features and intestinal microbiota in Chinese patients with ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:4722-4737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kropp C, Le Corf K, Relizani K, Tambosco K, Martinez C, Chain F, Rawadi G, Langella P, Claus SP, Martin R. The Keystone commensal bacterium Christensenella minuta DSM 22607 displays anti-inflammatory properties both in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep. 2021;11:11494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kropp C, Tambosco K, Chadi S, Langella P, Claus SP, Martin R. Christensenella minuta protects and restores intestinal barrier in a colitis mouse model by regulating inflammation. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2024;10:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/