Published online Jan 14, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i2.113810

Revised: October 1, 2025

Accepted: November 24, 2025

Published online: January 14, 2026

Processing time: 130 Days and 22.6 Hours

Data comparing the outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ablation by multibipolar radiofrequency ablation (mbp-RFA) and microwave ablation (MWA) are lacking. This study compares safety and efficacy of the two techniques in treatment-naive HCC.

To compare the risk of local tumor progression (LTP) according to the technique; secondary endpoints included technique efficacy rate at one-month, overall sur

A bi-institutional retrospective analysis of patients undergoing treatment-naive HCC ablation by either technique was performed. Inverse probability of treatment weighting was used to compare the two groups. Mixed effects multivariate Cox regression was applied to identify risk factors for LTP.

A total of 362 patients (mean age, 66.1 ± 6.2 years, 308 men) were included, of which 242 (323 tumors) treated by mbp-RFA and 120 (168 tumors) by MWA. After a median follow-up of 27 months, cumulative LTP was 11.4% after mbp-RFA and 25.2% after MWA. Independent risk factors for LTP at multivariate analysis were MWA (hazard ratio = 2.85, P < 0.001) and tumor size (hazard ratio = 1.08, P < 0.001). Two-year LTP-free survival was higher after mbp-RFA than MWA regardless of size (< 3 cm: 96% vs 87.1%, P < 0.01; ≥ 3 cm: 87.5% vs 74%, P = 0.04). Technique efficacy rate was higher after mbp-RFA (94.1% vs 87.5%, P = 0.01). No difference was observed in major compli

Mbp-RFA leads to better local tumor control of treatment-naïve HCC than MWA regardless of tumor size and has better primary efficacy, while maintaining a comparable safety profile.

Core Tip: There is limited data comparing multibipolar radiofrequency ablation (mbp-RFA) and microwave ablation (MWA) for treating hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). This study analyzed 362 patients with newly diagnosed HCC who underwent either mbp-RFA (242 patients, 323 tumors) or MWA (120 patients, 168 tumors). Results showed that mbp-RFA provided better local tumor control, with a lower local tumor progression rate (11.4% vs 25.2%) and a higher complete ablation rate (94.1% vs 87.5%) compared to MWA. The advantage of mbp-RFA was particularly significant for tumors larger than 3 cm, where MWA had a local tumor progression rate of 60.9% vs 21.6% with mbp-RFA. Despite these differences in efficacy, both techniques had similar major complication rates (9.5% vs 7.5%). These findings suggest that mbp-RFA is a more effective option for larger, treatment-naïve HCC tumors while maintaining a comparable safety profile.

- Citation: Bahloul C, Rode A, Pradat P, Milot L, Dumortier J, Merle P, Mabrut JY, Boussel L, Della Corte A. Multibipolar radiofrequency vs single needle microwave ablation for the treatment of newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(2): 113810

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i2/113810.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i2.113810

Thermal ablation is a recognized treatment option of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) at the very early stage (single tumor not larger than 2 cm), or within the Milan criteria unsuitable for resection or transplantation[1]. Local tumor progression (LTP) remains a limitation, with incidences of up to 40%[2]. Predictive factors for LTP include tumor size (> 3 cm), subcapsular location, and proximity to major vessels[2,3]. Microwave ablation (MWA) has widely replaced radiofrequency ablation (RFA) due to resistance to heat-sink effect and lower rates of LTP[4-6], especially for tumors larger than 2.5 cm[7,8]. However, LTP remains common, particularly in tumors > 3 cm, where it exceeds 30% at one year[9].

Multibipolar RFA (mbp-RFA), described by Frericks et al[10], involves multiple needle positioning at the tumor’s borders, avoiding direct puncture[11]. Differently from multi monopolar RFA (termed cluster RFA), in mbp-RFA each needle couple works as a dipole, producing a centripetal ablation zone. While its outcomes have proven superior to cluster RFA[12,13] and comparable to laparoscopic resection for HCC up to 5 cm[14], comparative data with MWA are lacking. The aim of this study is to retrospectively compare safety and efficacy of MWA and mbp-RFA in a cohort of patients treated for a newly diagnosed early-stage HCC.

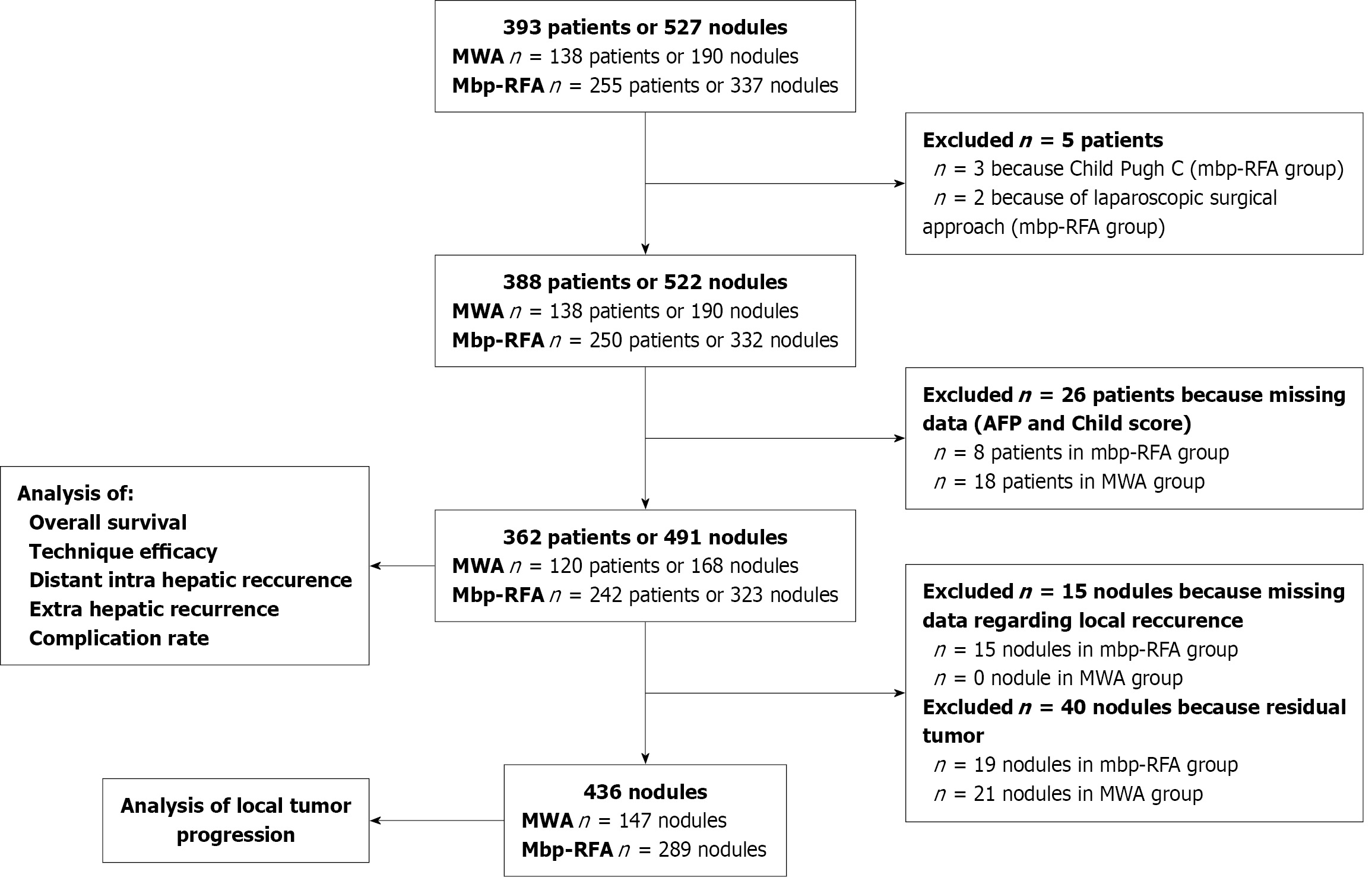

A retrospective study (January 2014 to January 2021) across two hospitals in Lyon, France (Croix-Rousse, institution A, and Edouard Herriot, institution B), was conducted, involving 362 patients (242 mbp-RFA; 120 MWA) and 436 nodules (323 mbp-RFA, 168 MWA. Patients with treatment-naive liver-limited HCC, who underwent ablation either as curative treatment or bridge to transplant, were selected. Exclusion criteria were Child Pugh C score, laparoscopic approach, prior/concurrent HCC treatments.

Clinical and imaging data were collected per-patient and per-nodule (Table 1). Tumor proximity to large vessels was defined according to definition by Kang et al[3] as tumor contact with a vessel ≥ 3 cm in diameter. Each patient presented on average 1.38 HCC nodules at the time of the intervention. A detailed flow-chart for sequential patient and nodule exclusion is provided in Figure 1. Diagnosis of HCC was confirmed by percutaneous biopsy or based on the non-invasive criteria of the European Association for the Study of the Liver[15].

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 362) | Nodules (n = 436) | ||||

| MWA (n = 120) | Mbp-RFA (n = 242) | P value | MWA (n = 147) | Mbp-RFA (n = 289) | P value | |

| Age in years (IQR) | 65.52 (59.1-71.7) | 66.33 (59.3-72.2) | P = 0.81 | |||

| Male | 97 (80.8) | 211 (87.2) | P = 0.11 | |||

| Cirrhosis | 117 (97.5) | 226 (93.4) | P = 0.1 | |||

| Cirrhosis aetiologies | ||||||

| Viral hepatitis | 19 (15.8) | 44 (18.2) | P = 0.91 | |||

| NASH | 23 (19.2) | 44 (18.2) | ||||

| Alcoholic | 41 (34.2) | 74 (30.6) | ||||

| Other/mixed | 20 (16.7) | 39 (16.1) | ||||

| Child Pugh | ||||||

| Child Pugh A | 99 (82.5) | 211 (87.2) | P = 0.23 | |||

| Child Pugh B | 21 (17.5) | 31 (12.8) | ||||

| Platelet count | ||||||

| < 100 G/L | 47 (39.2) | 82 (33.9) | P = 0.32 | |||

| ≥ 100 G/L | 73 (60.8) | 160 (66.1) | ||||

| AFP | ||||||

| < 10 ng/mL | 86 (71.7) | 159 (65.7) | P = 0.39 | |||

| 10-100 ng/mL | 27 (22.5) | 60 (24.8) | ||||

| > 100 ng/mL | 7 (5.8) | 23 (9.5) | ||||

| Number of nodules treated per patient | 1.41 | 1.34 | P = 0.16 | |||

| Histological proof | 41 (34.2) | 198 (81.8) | P < 0.005 | |||

| Size | ||||||

| < 20mm | 69 (46.9) | 93 (32.2) | P < 0.001 | |||

| 20-30 mm | 55 (37.4) | 108 (37.4) | ||||

| ≥ 30 mm | 23 (15.6) | 88 (30.4) | ||||

| Tumour near large vessel | 20 (13.6) | 36 (12.5) | P = 0.735 | |||

| Subcapsular tumour | 74 (50.3) | 167 (57.8) | P = 0.139 | |||

| Proximity to the gallbladder | 4 (2.7) | 18 (6.2) | P = 0.114 | |||

| Segmental portal thrombosis | 0 | 3 (1) | P = 0.554 | |||

| Operator experience (months) | 107 (38-360) | 303 (105-331) | P = 0.026 | |||

| Guidance modality | ||||||

| By ultrasound alone | 49 (33.3) | 288 (99.7) | P < 0.001 | |||

| By scanner alone | 7 (4.8) | 1 (0.3) | ||||

| Mixed guidance (ultrasound + scanner) | 91 (61.9) | 0 | ||||

| Nodules treated per center | P < 0.001 | |||||

| Institution A | 35 (23.8) | 289 (100) | ||||

| Institution B | 112 (76.2) | 0 (0) | ||||

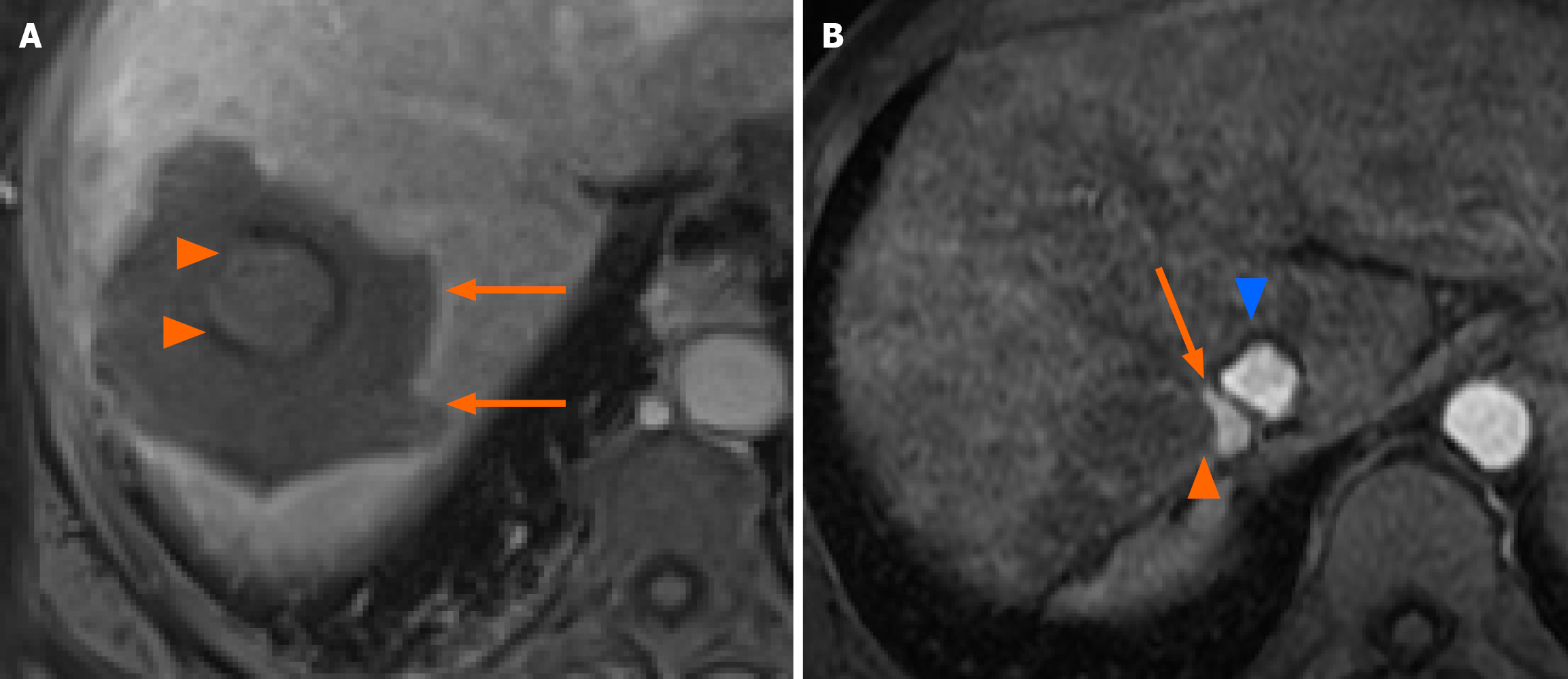

All procedures were performed under general anesthesia by interventional radiologists with ≥ 3 years of experience in thermal ablation of the liver. Concerning guidance modalities, in institution A needle positioning was performed under real-time ultrasound monitoring, with the addition of contrast-enhanced ultrasound and preoperative computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) fusion imaging for poorly visible tumors. In institution B, a combination of ultrasound and CT guidance was utilized. Verification of immediate post-ablation tumor coverage was done during general anesthesia by contrast-enhanced ultrasound in institution A and by contrast-enhanced CT scan in institution B. MWA was performed by Emprint generator (Medtronic) in institution A and Amika generator (Ablatech) in institution B. Mbp-RFA was performed by multipolar internally cooled-tip CelonProSurge™ (CelonPOWER System OLYMPUS Medical). Ablation power and time were adjusted to achieve complete tumor coverage with > 1 cm safety margins when feasible according to manufacturer instructions (Ablation Zone Charts, R0065469, Instructions for Use, Emprint™). In mbp-RFA, 2 to 5 needles were utilized according to tumor shape and size with an ideal 2-3 cm spacing. A representative example of a complete ablation zone is shown in Figure 2A. Treatment efficacy was assessed one month after the procedure by gadolinium-enhanced MRI or CT if the former was not feasible. Follow up was then performed every 3 months by MRI or CT scan over 2 years, and every 6 months thereafter.

All exams were interpreted by radiologists specialized in digestive imaging with ≥ 5 years of experience. Following standard terminology reporting criteria by Ahmed et al[16], complete tumor coverage by the ablation zone at one month was termed primary efficacy and LTP was defined as appearance of viable disease at the ablation margins following a negative one-month imaging. A representative example of an LTP is shown in Figure 2B.

The primary endpoint was to compare the risk of LTP according to the two techniques. Secondary endpoints were the comparison of: (1) Complete ablation rate (technique efficacy); (2) Intrahepatic distant recurrence rates; (3) Extrahepatic recurrence rates; (4) Overall survival (OS); and (5) Major complication rates according to the Society of Interventional Radiology classification[17]. A supplemental analysis comparing MWA outcome (primary efficacy and LTP rate) according to the two institutions was also carried out to account for potential bias and is reported in the appendix (Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages, and continuous variables are presented as median and interquartile range. For categorical variables, comparisons between the two groups were performed using Fisher’s exact test. For continuous variables, comparisons between the two groups were performed using Student t-test in case of normal distribution or by the Mann-Whitney test in case of skewed distribution. Normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

To reduce selection and confusion biases, we calculated an inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) propensity score and used stabilized weights to maintain an appropriate type I error rate[18]. The propensity score was calculated at the patient level using a multivariable logistic regression model with allocation of MWA as the endpoint. All analyses were performed using the stabilized weight as a covariable. For the primary endpoint of LTP, a per-nodule analysis was performed. LTP-free survival (LTPFS) rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method for stabilized IPTW-adjusted cohorts. The date of the patient’s last imaging follow-up was taken as the censoring date; patients undergoing liver transplantation were censored at the date of the last pre-transplant imaging. Comparison of Kaplan-Meier curves was performed using the log-rank test.

A mixed effects cox regression model analysis was conducted to identify factors potentially associated with LTPFS, adjusted for the inclusion of patients with a varying number of nodules. Variables with a P value < 0.10 in univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate model. A competing risk analysis was also performed to account for the occurrence of liver transplantation and death. For the secondary endpoints (OS, and distant intrahepatic recurrence rate, major complication rates) a per-patient analysis was carried out. The date of the patient’s last clinical follow-up was taken as the censoring date. All tests were two sided and a P value < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Concerning characteristics of the 362 patients included in the study, patients in the mbp-RFA group more frequently had a histological proof for HCC diagnosis (81.8% vs 34.42%, P < 0.005), as shown in Table 1. No other significant differences were observed. Concerning the characteristics of the 436 nodules included for LTP analysis, in the MWA group 112 nodules (76.2%) were treated at institution B and 35 nodules (23.8%) at the institution A. All 289 nodules in the mbp-RFA group were treated at institution A. No significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding subcapsular location and proximity to large vessels. Tumors treated by mbp-RFA were significantly larger with higher rates of HCCs ≥ 30 mm (30.4% vs 15.6%, P < 0.001); interventional radiologists performing mbp-RFA had a significant advantage in months of experience in ablation procedures compared to those performing MWA (303 months vs 107 months, P = 0.026). Patient and tumor characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Intraprocedural needle repositioning was performed in 50/323 cases (15.5%) in the mbp-RFA group and 23/168 cases (13.7%) in the MWA group, P = 0.6. Complete tumor ablation at one month (primary technique efficacy) was significantly higher in the mbp-RFA group (304/323, 94.1% vs 147/168, 87.5%, P = 0.01). For HCCs < 30 mm, residual tumor occurred for 17/141 (12.1%) nodules treated by MWA vs 15/227 (6.6%) in mbp-RFA group. As for HCC ≥ 30 mm, residual tumor occurred for 4/27 (14.8%) nodules treated by MWA vs 4/96 (4.2%) in the mbp-RFA group (Table 2). Out of the 19 patients with residual tumor at one-month imaging post-mbp-RFA, 13 underwent successful reablation, 4 underwent further follow-up with residual tumor stability, one underwent liver transplantation, and 1 underwent transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). Out of the 21 patients with residual tumor one month post MWA, 9 underwent successful reablation, 6 underwent follow-up with residual tumor stability, 4 underwent TACE and 1 underwent surgical resection.

| Residual tumor (n = 491 nodules) | Local tumor progression (n = 436 nodules) | |||

| Total | MWA (n = 168) | 21 (12.5) | MWA (n = 147) | 37 (25.2) |

| Mbp-RFA (n = 323) | 19 (5.9) | Mbp-RFA (n = 289) | 33 (11.4) | |

| P value | 0.01 | P value | 0.002 | |

| < 30 mm | MWA (n = 141) | 17 (12.1) | MWA (n = 124) | 23 (18.5) |

| Mbp-RFA (n = 227) | 15 (6.6) | Mbp-RFA (n = 201) | 17 (7) | |

| P value | 0.071 | P value | < 0.002 | |

| ≥ 30 mm | MWA (n = 27) | 4 (14.8) | MWA (n = 23) | 14 (60.9) |

| Mbp-RFA (n = 96) | 4 (4.2) | Mbp-RFA (n = 88) | 19 (21.6) | |

| P value | 0.069 | P value | 0.04 | |

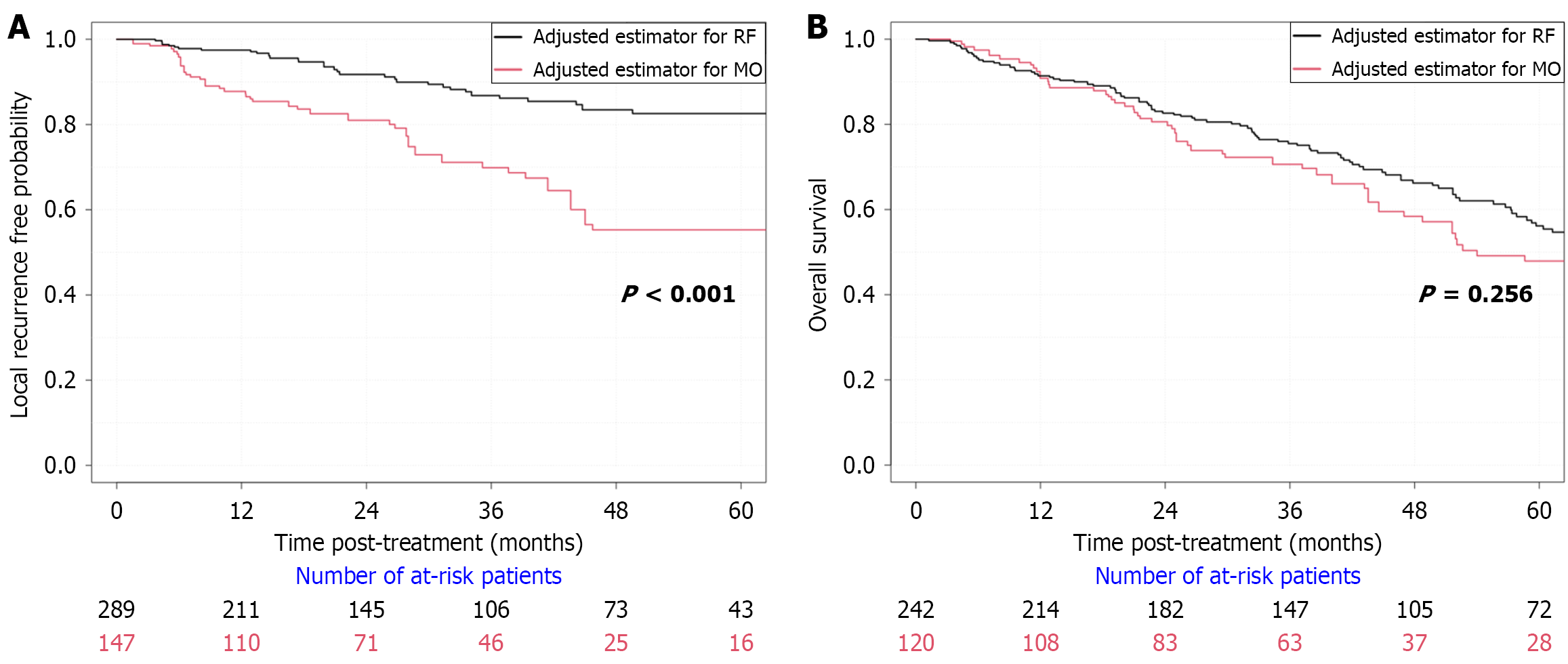

Cumulative incidence of LTP at final follow-up (median: 27 months) was 11.4% in the mbp-RFA group and 25.2% in the MWA group (P = 0.002, log-rank test). One- and two-year LTPFS rates were 96.9% and 93.4% in the mbp-RFA group, compared to 88.4% and 85.0% in the MWA group. For HCCs < 30 mm, cumulative incidence of LTP at final follow-up was 7% in the mbp-RFA and 18.5% in the MWA group (P < 0.01, log-rank test). One-year and 2-year LTPFS were 99% and 96% in the mbp-RFA group vs 88.5% and 87.1% in the MWA group. As for HCC ≥ 30 mm, cumulative incidence of LTP at final follow-up was 21.6% in the mbp-RFA and 60.9% in the MWA group (P = 0.04, log-rank test, Table 2). One-year and two-year LTPFS were 92.1% and 87.5% in the mbp-RFA group vs 82.6% and 74% in the MWA group.

In univariate analysis (IPTW mixed effects cox regression), MWA was identified as a risk factor for LTP [hazard ratio (HR) = 2.41, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.48-3.90, P < 0.001, Figure 3]. In the multivariate Cox model, two variables were identified as independent risk factors of LTP as shown in Table 3. MWA led to a 185% higher risk of developing LTP compared to mbp-RFA, HR = 2.85 (95%CI: 1.69-4.81), P < 0.001. Tumor size led to an 8% higher risk of developing LTP for additional millimetre in the long axis, HR = 1.08 (95%CI: 1.05-1.11), P < 0.001. Following a multivariate competing risk regression analysis, addressing liver transplantation and death as competing events, MWA was the only independent risk factor for LTP [MWA: HR = 2.35 (95%CI: 1.3-4.3), P = 0.005].

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | Multivariable analysis (competing risks) | ||||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 1.03 (1.002-1.06) | 0.037 | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | 0.192 | 1.02 (0.98-1.06) | 0.15 |

| Sex (male vs female) | 0.62 (0.31-1.25) | 0.182 | - | - | - | - |

| Child Pugh (B vs A) | 1.85 (0.94-3.65) | 0.074 | 1.55 (0.75-3.2) | 0.233 | 0.72 (0.27-1.95) | 0.52 |

| Platelet count (for 50.000 additional platelet) | 1.09 (0.90-1.33) | 0.376 | - | - | - | - |

| AFP (for 100 ng/mL additional) | 1.10 (1.08-1.13) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (0.99-1.11) | 0.080 | 1 (0.94-1.01) | 0.48 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 1.08 (1.06-1.11) | < 0.001 | 1.08 (1.05-1.11) | < 0.001 | 1.07 (1.05-1.1) | 0.06 |

| Subcapsular HCC | 0.97 (0.60-1.57) | 0.900 | - | - | - | - |

| Proximity of HCC to large vessels | 1.29 (0.68-2.42) | 0.435 | 1.34 (0.69-2.59) | 0.393 | 1.14 (0.59-2.2) | 0.7 |

| Number of HCC nodules | 0.88 (0.71-1.08) | 0.224 | - | - | - | - |

| Treatment by ultrasound guidance alone | 0.40 (0.10-1.59) | 0.193 | - | - | - | - |

| Treatment by ultrasound and CT guidance | 0.92 (0.22-3.79) | 0.908 | - | - | - | - |

| Operator experience (per additional month) | 1.00 (0.998-1.002) | 0.963 | 1.00 (0.999-1.002) | 0.702 | 1.00 (0.999-1) | 0.9 |

| Thermoablation technique (MWA vs mbp-RFA) | 2.41 (1.48-3.90) | < 0.001 | 2.85 (1.69-4.81) | < 0.001 | 2.35 (1.3-4.3) | 0.005 |

There was no significant difference in survival between the two groups (Figure 3B): Death during follow-up was observed in 57/120 (47.5%) patients treated with MWA vs 107/242 (44.2%) treated with mbp-RFA, P = 0.554. The 3- and 5-year OS rates were respectively 70.8% and 58.3% in the MWA group vs 76% and 63.6% in the mbp-RFA, P = 0.286 and P = 0.328. Among the 164 recorded deaths in the study, the leading cause was non-liver or cancer-related deaths, with 39 cases (23.8%). Liver failure or complications from cirrhosis accounted for 37 cases (22.6%), while HCC progression was responsible for 31 cases (18.9%). A combination of HCC progression and liver failure contributed to 13 cases (7.9%), and other cancers accounted for 22 cases (13.4%). Post-operative complications from HCC treatment were reported in 3 cases (1.8%). Additionally, 19 cases (11.6%) had unknown causes. No differences in causes of mortality were highlighted between the two treatment groups (P = 0.322). No significant difference between the two groups was observed regarding risk of intrahepatic distant recurrence (P = 0.623) nor extrahepatic recurrence (P = 0.557). A total of 63 patients were transplanted (17.4%). There was no significant difference in graft HCC recurrence between the two groups: 1/18 cases were observed in the MWA group (5.6%) and 1/42 cases in the mbp-RFA group (2.4%), P = 0.514.

The major complication rate was 7.5% in the MWA group, 9.5% in the mbp-RFA group (P = 0.527). Details of complications and adverse events are given in Table 4.

| Society of interventional radiology classification | Treatment group | |

| MWA, n = 9 (7.5%) | Mbp-RFA, n = 23 (9.5%) | |

| Grade C | 4 (3.3%): 2 patients with portal thrombus requiring anticoagulation; 2 patients with symptomatic undrained pleural effusion | 9 (3.7%): 3 patients with portal thrombus requiring anticoagulation; 2 patients with symptomatic undrained pleural effusion; 1 patient with ascitic decompensation treated with diuretics; 2 patients with pneumopathy treated with antibiotics; 1 patient with soft tissue hematoma with pain |

| Grade D | 4 (3.3%): 2 patients with symptomatic pleural effusion with indication for pleural drainage; 1 patient with cessation of the procedure after treatment of the first nodule for dyspnea, transfer to intensive care; 1 patient with drained pneumothorax | 13 (5.4%): 8 patients with symptomatic pleural effusion with indication for pleural drainage; 2 patients with reactive cholecystitis (1 operated, 1 medically treated); 1 patient with an arterio-portal fistula requiring remote embolization; 2 patients with an infection of the surgical site (one with pre-hepatic collection, on with intra-hepatic collection in contact with the scar) |

| Grade E | 1 (0.8%): 1 patient with necrosis of the left lobe with stay in intensive care | 1 (0.4%): 1 biliopleural fistula requiring drainage and thoracoscopy |

| Grade F | 0 | 0 |

In this retrospective bi-institutional study, mbp-RFA demonstrated superior local tumor control compared to MWA, with a lower LTP rate (11.4% vs 25.2%). Multivariate analysis identified MWA (HR = 2.85) and tumor size (HR = 1.08) as independent risk factors for LTP. Technique efficacy at one-month imaging was significantly higher for mbp-RFA (94.1% vs 87.5%). No differences in OS, intrahepatic distant recurrence, extrahepatic recurrence and post-transplant HCC recurrence were observed. Safety profiles were comparable, with major complication rate of 9.5% for mbp-RFA and 7.5% for MWA, and no treatment-related deaths. For both techniques, observed cumulative LTP rates fall within previously reported ranges (25.7% after MWA, vs 10%-30% in the literature[7]; 11.4% after mbp-RFA, vs 10%-12% in the literature[12,19]).

In our study, better outcome after mbp-RFA was especially evident on the subgroup of tumors exceeding 3 cm (technique efficacy in 95.8% vs 85.2%). For both groups, the results are superior to available data for monopolar radiofrequency (77%). LTP rate was 21.6% after mbp-RFA vs 60.9% after MWA. Only one study specifically addressing MWA of HCC between 3 and 5 centimeters found a 31% rate of local recurrence after a 12-month follow-up[9], which is exceeding the observed one- and two-year LTP rate of 17.4% and 26% in our cohort. According to Hocquelet et al[12], peripheral multi-probe placement enables complete vessel coagulation, disrupting vascularization and achieving full necrosis even in larger tumors. In contrast, the application of single needle MWA to larger tumors is limited by the physical properties of centrifugal heat diffusion, which rarely result in ablation zones exceeding 4 cm in largest diameter on ex vivo models[20].

Interestingly, the global local tumor control obtained by mbp-RFA was comparable, if not superior, to the results previously reported for combination of ablation and TACE on HCCs between 3 cm and 5 cm, with a similar safety profile[21]. In particular, a previous single-center study on combination of MWA and TACE reported an initial complete response of 92.1% (vs 95.8% in our study)[22]; another study investigating the combination of balloon occluded monopolar RFA combined with TACE reported an LTP rate of 58.1% (vs 21.6% in our study)[23]. These results may advocate the role of mbp-RFA in this specific subset of patients for which a validated gold standard is not provided by international guidelines. A significant difference in local tumor control was also observed in tumors < 3 cm. In this subpopulation, technique efficacy rate was observed in 6.6% tumors treated by mbp-RFA vs 12.1% tumors treated by MWA, and LTP rate was 7% after mbp-RFA vs 18.5% after MWA. Interestingly, the LTP rate observed after mbp-RFA in this subpopulation was lower than the lowest reports in literature for MWA (9%)[8,24].

One possible explanation is that mbp-RFA enables the operator to tailor the shape and size of the ablation zone by multi-needle positioning, allowing to achieve effective local tumor control even in challenging locations and irregularly shaped nodules[11,19]. Another reason is that even in poorly visible nodules, complete ablation is more likely to occur with a multi-needle centripetal technique than with a single-needle technique, where optimal positioning at the core of the lesion is required.

Proximity to vessels did not affect LTP, consistent with mbp-RFA’s capacity to offset heat-sink effects by interposing needles near vessels[13]. The safety profile between the two techniques was comparable (major complication rate 9.5% after mbp-RFA vs 7.5% after MWA). No hemorrhagic complications were observed in the mbp-RFA group despite multiple needle positioning. Relatively small needle caliber and the correct use of track ablation may have contributed to the prevention of bleeding. While LTP can impact OS[25], no survival difference was found in this cohort, possibly due to effective salvage treatments and transplant availability. However, improved local control could be particularly advantageous for transplant candidates by reducing dropout risk[26].

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the retrospective design introduces a potential selection bias. However, the use of propensity score matching and the absence of relevant difference in baseline analysis favoring mbp-RFA over MWA account for a reasonable robustness of presented data. Another limitation of the study is the difference in operator experience. Mbp-RFA requires a specific skill set since the treatment usually relies on multiple needles placement, with convergent positioning for effective lesion coverage. In our study, operators in the mbp-RFA group had an average longer experience in percutaneous liver ablation and all mbp-RFA procedures were performed in institution A. However, operator experience was not an independent predictor of LTP and institutional outcomes after MWA were consistent, suggesting limited operator bias.

In expert hands, mbp-RFA could be a better option for local tumor control of HCC, despite lesion size. The excellent results obtained on tumors exceeding 3 cm in maximum diameter call for an important role of mbp-RFA in this specific patient population. Further prospective studies may validate these results and lead to optimization of treatment protocols.

This work was performed within the framework of the IHU EVEREST (ANR-23-IAHU-0008), within the program “Investissements d’Avenir” operated by the French National Research Agency (ANR).

| 1. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2025;82:315-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 338.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Kim YS, Lim HK, Rhim H, Lee MW, Choi D, Lee WJ, Paik SW, Koh KC, Lee JH, Choi MS, Gwak GY, Yoo BC. Ten-year outcomes of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation as first-line therapy of early hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of prognostic factors. J Hepatol. 2013;58:89-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kang TW, Lim HK, Lee MW, Kim YS, Rhim H, Lee WJ, Paik YH, Kim MJ, Ahn JH. Long-term Therapeutic Outcomes of Radiofrequency Ablation for Subcapsular versus Nonsubcapsular Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Propensity Score Matched Study. Radiology. 2016;280:300-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huang S, Yu J, Liang P, Yu X, Cheng Z, Han Z, Li Q. Percutaneous microwave ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma adjacent to large vessels: a long-term follow-up. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83:552-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | An C, Li WZ, Huang ZM, Yu XL, Han YZ, Liu FY, Wu SS, Yu J, Liang P, Huang J. Small single perivascular hepatocellular carcinoma: comparisons of radiofrequency ablation and microwave ablation by using propensity score analysis. Eur Radiol. 2021;31:4764-4773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bouda D, Barrau V, Raynaud L, Dioguardi Burgio M, Paulatto L, Roche V, Sibert A, Moussa N, Vilgrain V, Ronot M. Factors Associated with Tumor Progression After Percutaneous Ablation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Comparison Between Monopolar Radiofrequency and Microwaves. Results of a Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2020;43:1608-1618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Glassberg MB, Ghosh S, Clymer JW, Qadeer RA, Ferko NC, Sadeghirad B, Wright GW, Amaral JF. Microwave ablation compared with radiofrequency ablation for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver metastases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:6407-6438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dou Z, Lu F, Ren L, Song X, Li B, Li X. Efficacy and safety of microwave ablation and radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e29321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Veltri A, Gazzera C, Calandri M, Marenco F, Doriguzzi Breatta A, Fonio P, Gandini G. Percutaneous treatment of Hepatocellular carcinoma exceeding 3 cm: combined therapy or microwave ablation? Preliminary results. Radiol Med. 2015;120:1177-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Frericks BB, Ritz JP, Roggan A, Wolf KJ, Albrecht T. Multipolar radiofrequency ablation of hepatic tumors: initial experience. Radiology. 2005;237:1056-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Seror O. No touch radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a conceptual approach rather than an iron law. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2022;11:132-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hocquelet A, Aubé C, Rode A, Cartier V, Sutter O, Manichon AF, Boursier J, N'kontchou G, Merle P, Blanc JF, Trillaud H, Seror O. Comparison of no-touch multi-bipolar vs. monopolar radiofrequency ablation for small HCC. J Hepatol. 2017;66:67-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Loriaud A, Denys A, Seror O, Vietti Violi N, Digklia A, Duran R, Trillaud H, Hocquelet A. Hepatocellular carcinoma abutting large vessels: comparison of four percutaneous ablation systems. Int J Hyperthermia. 2018;34:1171-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mohkam K, Dumont PN, Manichon AF, Jouvet JC, Boussel L, Merle P, Ducerf C, Lesurtel M, Rode A, Mabrut JY. No-touch multibipolar radiofrequency ablation vs. surgical resection for solitary hepatocellular carcinoma ranging from 2 to 5 cm. J Hepatol. 2018;68:1172-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5593] [Cited by in RCA: 6416] [Article Influence: 802.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 16. | Ahmed M, Solbiati L, Brace CL, Breen DJ, Callstrom MR, Charboneau JW, Chen MH, Choi BI, de Baère T, Dodd GD 3rd, Dupuy DE, Gervais DA, Gianfelice D, Gillams AR, Lee FT Jr, Leen E, Lencioni R, Littrup PJ, Livraghi T, Lu DS, McGahan JP, Meloni MF, Nikolic B, Pereira PL, Liang P, Rhim H, Rose SC, Salem R, Sofocleous CT, Solomon SB, Soulen MC, Tanaka M, Vogl TJ, Wood BJ, Goldberg SN; International Working Group on Image-guided Tumor Ablation; Interventional Oncology Sans Frontières Expert Panel; Technology Assessment Committee of the Society of Interventional Radiology,; Standard of Practice Committee of the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe. Image-guided tumor ablation: standardization of terminology and reporting criteria--a 10-year update. Radiology. 2014;273:241-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 628] [Cited by in RCA: 953] [Article Influence: 79.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sacks D, McClenny TE, Cardella JF, Lewis CA. Society of Interventional Radiology clinical practice guidelines. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:S199-S202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1143] [Cited by in RCA: 1365] [Article Influence: 71.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xu S, Ross C, Raebel MA, Shetterly S, Blanchette C, Smith D. Use of stabilized inverse propensity scores as weights to directly estimate relative risk and its confidence intervals. Value Health. 2010;13:273-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 620] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Seror O, N'Kontchou G, Nault JC, Rabahi Y, Nahon P, Ganne-Carrié N, Grando V, Zentar N, Beaugrand M, Trinchet JC, Diallo A, Sellier N. Hepatocellular Carcinoma within Milan Criteria: No-Touch Multibipolar Radiofrequency Ablation for Treatment-Long-term Results. Radiology. 2016;280:611-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hui TCH, How GY, Chim MSM, Pua U. Comparative Study of Ablation Zone of EMPRINT HP Microwave Device with Contemporary 2.4 GHz Microwave Devices in an Ex Vivo Porcine Liver Model. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:2702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Young S, Golzarian J. Locoregional Therapies in the Treatment of 3- to 5-cm Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Critical Review of the Literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;215:223-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chen QF, Jia ZY, Yang ZQ, Fan WL, Shi HB. Transarterial Chemoembolization Monotherapy Versus Combined Transarterial Chemoembolization-Microwave Ablation Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tumors ≤5 cm: A Propensity Analysis at a Single Center. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2017;40:1748-1755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Saviano A, Iezzi R, Giuliante F, Salvatore L, Mele C, Posa A, Ardito F, De Gaetano AM, Pompili M; HepatoCATT Study Group. Liver Resection versus Radiofrequency Ablation plus Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization in Cirrhotic Patients with Solitary Large Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28:1512-1519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Potretzke TA, Ziemlewicz TJ, Hinshaw JL, Lubner MG, Wells SA, Brace CL, Agarwal P, Lee FT Jr. Microwave versus Radiofrequency Ablation Treatment for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Comparison of Efficacy at a Single Center. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27:631-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee MW, Kang D, Lim HK, Cho J, Sinn DH, Kang TW, Song KD, Rhim H, Cha DI, Lu DSK. Updated 10-year outcomes of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation as first-line therapy for single hepatocellular carcinoma < 3 cm: emphasis on association of local tumor progression and overall survival. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:2391-2400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Boros C, Sutter O, Cauchy F, Ganne-Carrié N, Nahon P, N'kontchou G, Ziol M, Grando V, Demory A, Blaise L, Dondero F, Durand F, Soubrane O, Lesurtel M, Laurent A, Seror O, Nault JC. Upfront multi-bipolar radiofrequency ablation for HCC in transplant-eligible cirrhotic patients with salvage transplantation in case of recurrence. Liver Int. 2024;44:1464-1473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/