Published online Dec 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i48.115244

Revised: October 28, 2025

Accepted: November 12, 2025

Published online: December 28, 2025

Processing time: 76 Days and 1.7 Hours

Li et al’s recent work on the risk factors for autoimmune gastritis provides clinical context for the vast majority of gastric neuroendocrine tumors (G-NETs). How

Core Tip: Clinical risk models identify patients with autoimmune gastritis who may develop neuroendocrine tumors, but pathology guides what to do next. We advocate for a “prognostic biopsy protocol” where pathologists report the specific stage of microscopic pre-cancerous lesions. Finding high-risk changes, especially dysplasia, serves as a clear trigger to intensify surveillance. This approach allows clinicians to manage risk proactively based on a patient’s real-time biology, rather than waiting for a visible tumor to develop.

- Citation: Wang CL, Zeng M, Luo Y. Unmasking the high-risk phenotype in autoimmune gastritis: A pathologist’s roadmap for the clinician. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(48): 115244

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i48/115244.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i48.115244

We have read with interest the article by Li et al[1] in the World Journal of Gastroenterology. Their analysis of 303 patients produced an effective predictive model incorporating five clinical and endoscopic features, providing a strong scientific basis for risk stratification. Although invaluable for identifying at-risk individuals, we aimed to explore how these findings can be combined with pathological data to guide a more dynamic and actionable approach to patient surveillance.

Endoscopic evaluation provides the initial evidence for the diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis (AIG). The hallmark endoscopic finding is “reverse atrophy”, characterized by a pale, thinned corpus mucosa with effacement of rugal folds and increased visibility of the submucosal vascular pattern[2-4]. Histologically, these macroscopic features directly correlate with the extensive loss of oxyntic glands, which are frequently replaced by fibrosis and metaplastic epithelium, such as the intestinal or pseudopyloric types[3,5,6]. While endoscopy identifies this high-risk atrophic field, visible changes represent only a fraction of the underlying pathology. The full spectrum of neoplastic risk is discernible only through microscopic examination of the tissue.

The primary targets for biopsy are discrete mucosal lesions such as nodules or polyps. Such lesions, often appearing as small erythematous nodules, are present in more than 10% of patients with AIG; however, their endoscopic morphology is non-specific and insufficient for diagnosis[7,8]. Histopathological assessment is indispensable for differentiating benign entities, such as hyperplastic or pseudopolyps, from incipient grade 1 gastric neuroendocrine tumors (G-NETs)[8,9]. Given that even diminutive nodules may harbor well-differentiated neoplasia, it is an established principle that any distinct nodularity within the atrophic corpus of a patient with AIG warrants targeted biopsy[5,10].

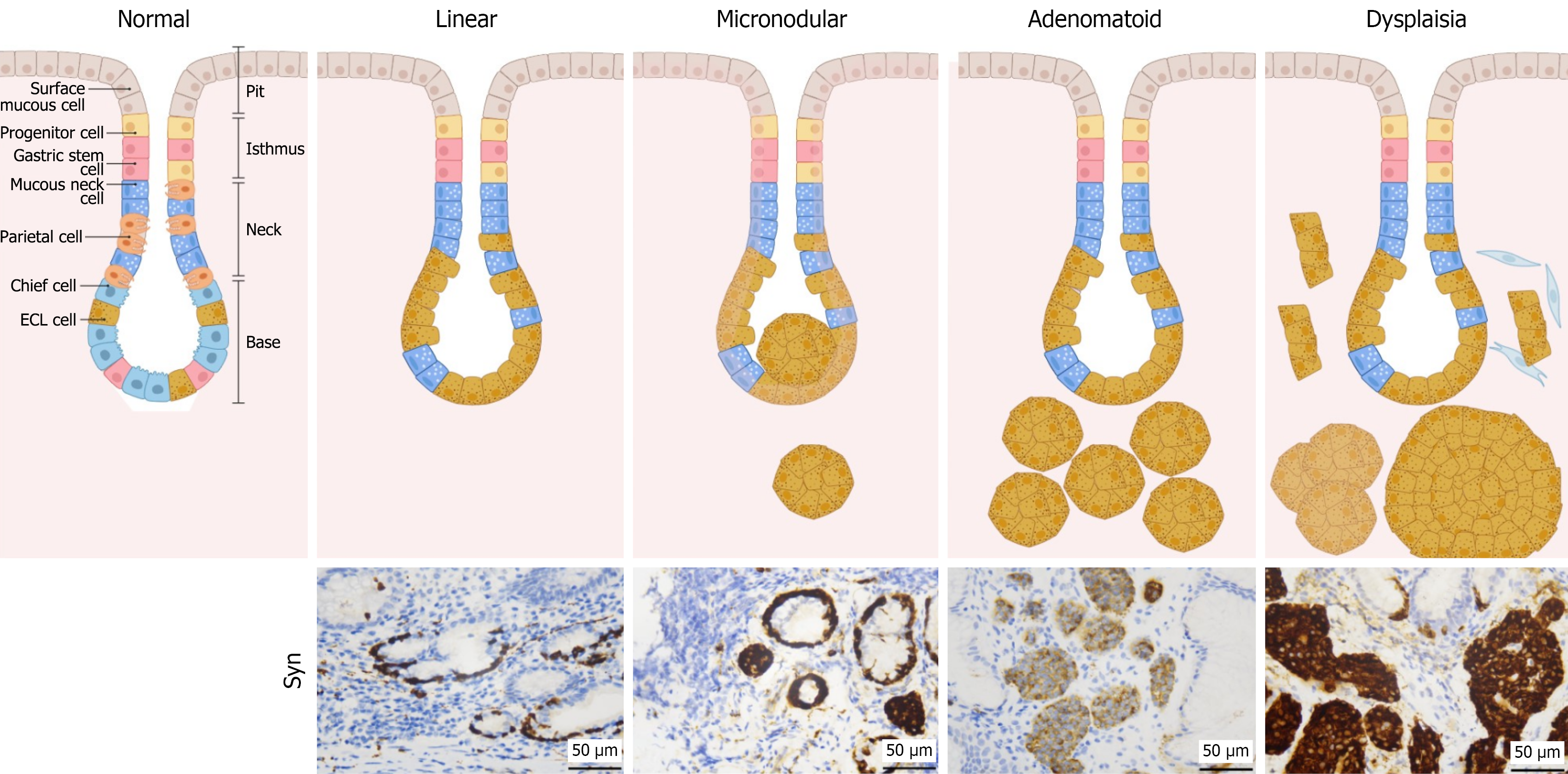

However, the most significant prognostic information often resides within the endoscopically unremarkable flat atrophic mucosa. Within this background milieu, precursor lesions of G-NETs develop, often without overt endoscopic signs. These microscopic alterations, encompassing a well-defined spectrum of enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell proliferation from linear hyperplasia to micronodular hyperplasia, and ultimately dysplasia, are the most powerful predictors of subsequent tumor development[3,5]. The identification and grading of these occult lesions are exclusively within the purview of the pathologist. This process translates general endoscopic observations into a specific biological risk profile, thereby facilitating precise and actionable assessment of the patient’s neoplastic risk.

In AIG, autoimmune-mediated destruction of parietal cells results in achlorhydria and consequent compensatory hypergastrinemia[11,12]. Sustained hypergastrinemia exerts a potent trophic effect on ECL cells and induces a well-defined spectrum of precursor lesions. This histopathological continuum, first identified by Solcia et al[13], progresses sequentially from linear hyperplasia to micronodular and adenomatoid hyperplasia, ultimately culminating in ECL cell dysplasia, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Although low-grade hyperplasia is a common finding, the development of advanced precursor lesions represents a critical inflection point in neoplastic risk. Specifically, the presence of severe hyperplasia, or most significantly ECL cell dysplasia, are powerful independent predictors of G-NET development[14]. The identification of dysplasia, a lesion characterized by increased architectural complexity, is particularly ominous, elevating the risk of tumor development by more than 20-fold[15-17].

Crucially, the diagnostic threshold for an overt Type 1 G-NET is not subjective, but is defined by objective size-based criteria according to World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines: The presence of a lesion exceeding 0.5 mm in diameter or one that has invaded the submucosa[14,18]. Therefore, a gastric biopsy provides far more than a binary assessment of malignancy. It offers a definitive staging of the precursor field, effectively locating the patient along this well-defined carcinogenic pathway and enabling a risk assessment with greater precision than can be achieved using clinical features alone.

The predictive model developed by Li et al[1] provides an effective framework for identifying patients with AIG who have entered a well-documented continuum toward neuroendocrine neoplasia. To translate this risk stratification into a precise clinical management, we recommend the use of a “prognostic biopsy protocol”. In this pathology-centric framework, histopathological analysis translates endoscopic findings into actionable prognostic indicators. Therefore, gastric biopsy is not merely a diagnostic sample, but also an essential tool for biological staging, providing a definitive assessment of the patient’s exact position along the neoplastic pathway.

This trajectory is marked by distinct histological milestones that, when actively reported by a pathologist, signify escalating risk. The presence of linear and micronodular hyperplasia confirms that the gastrin-driven proliferative process is active and validates the need for continued surveillance[18]. Critical progression is marked by adenomatoid hyperplasia, which represents the coalescence of precursor lesions. The final and most significant prognostic threshold is the identification of ECL cell dysplasia, characterized by fused micronodules or micro-infiltrative architectural patterns[18]. As the immediate precursor to invasive neoplasia, the discovery of dysplasia should trigger a more intensive surveillance plan, a recommendation justified by evidence that established G-NETs are consistently associated with such high-risk changes in the background mucosa[15,19,20]. While our histopathological framework provides a biological rationale for this intensification, defining precise evidence-based surveillance intervals for these high-risk patients remains a critical challenge for prospective clinical studies and guideline committees.

Once an overt G-NET is diagnosed, its biological potential must be formally graded to provide a quantitative risk assessment. This objective measure of proliferation, determined by mitotic count and Ki-67 labeling index, is the cornerstone of the WHO grading system[18]. A report of a grade 1 G-NET (Ki-67 < 3% and mitotic count < 2/2 mm2) defines an indolent neoplasm with low metastatic potential, accounting for the vast majority of tumors in the AIG setting. Conversely, grade 2 G-NETs (Ki-67 3%-20% and mitotic count 2/2 mm2 to 20/2 mm2) represent a tumor with more aggressive biological behavior, necessitating more comprehensive staging and management.

This pathology-centric framework empowers clinicians to act on objective microscopic milestones rather than waiting for the development of macroscopically visible tumors. It fundamentally shifts the paradigm of patient management from a static, interval-based strategy to a dynamic, risk-adapted approach in which clinical decisions are precisely tailored to the evolving biological landscape of the patient.

In summary, the neoplastic risk of AIG is best managed using a histopathologically guided dynamic surveillance strategy. The well-defined spectrum of ECL cell precursor lesions provides clear, actionable thresholds for clinical decision making. The identification of high-risk changes, such as dysplasia, should prompt the immediate intensification of surveillance. This framework, which pairs the staging of precursor lesions with the definitive grading of overt G-NETs, allows for a rational, biology-driven approach that is superior to static protocol-based monitoring.

| 1. | Li YM, Guo WJ, Deng C, Luo J, Shi YF, Zhu D, Wei QL, Zhang MG, Du SY, Tan HY. Risk assessment of type I gastric neuroendocrine tumors based on endoscopic and clinical features of autoimmune gastritis. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:111449. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kyrlagkitsis I, Karamanolis DG. Premalignant lesions and conditions for gastric adenocarcinoma: diagnosis, management and surveillance guidelines. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:592-600. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Shah SC, Piazuelo MB, Kuipers EJ, Li D. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Atrophic Gastritis: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1325-1332.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 64.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, Rokkas T, Gisbert JP, Liou JM, Schulz C, Gasbarrini A, Hunt RH, Leja M, O'Morain C, Rugge M, Suerbaum S, Tilg H, Sugano K, El-Omar EM; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Gut. 2022;gutjnl-2022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 852] [Article Influence: 213.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lenti MV, Rugge M, Lahner E, Miceli E, Toh BH, Genta RM, De Block C, Hershko C, Di Sabatino A. Autoimmune gastritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 40.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rugge M, Genta RM, Malfertheiner P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, El-Serag H, Graham DY, Kuipers EJ, Leung WK, Park JY, Rokkas T, Schulz C, El-Omar EM; RE. GA.IN; RE GA IN. RE.GA.IN.: the Real-world Gastritis Initiative-updating the updates. Gut. 2024;73:407-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Terao S, Suzuki S, Yaita H, Kurahara K, Shunto J, Furuta T, Maruyama Y, Ito M, Kamada T, Aoki R, Inoue K, Manabe N, Haruma K. Multicenter study of autoimmune gastritis in Japan: Clinical and endoscopic characteristics. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Kamada T, Watanabe H, Furuta T, Terao S, Maruyama Y, Kawachi H, Kushima R, Chiba T, Haruma K. Diagnostic criteria and endoscopic and histological findings of autoimmune gastritis in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:185-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kamada T, Maruyama Y, Monobe Y, Haruma K. Endoscopic features and clinical importance of autoimmune gastritis. Dig Endosc. 2022;34:700-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Solcia E, Rindi G, Fiocca R, Villani L, Buffa R, Ambrosiani L, Capella C. Distinct patterns of chronic gastritis associated with carcinoid and cancer and their role in tumorigenesis. Yale J Biol Med. 1992;65:793-804; discussion 827. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Cives M, Strosberg JR. Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:471-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 424] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Sok C, Ajay PS, Tsagkalidis V, Kooby DA, Shah MM. Management of Gastric Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31:1509-1518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Solcia E, Bordi C, Creutzfeldt W, Dayal Y, Dayan AD, Falkmer S, Grimelius L, Havu N. Histopathological classification of nonantral gastric endocrine growths in man. Digestion. 1988;41:185-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vanoli A, La Rosa S, Luinetti O, Klersy C, Manca R, Alvisi C, Rossi S, Trespi E, Zangrandi A, Sessa F, Capella C, Solcia E. Histologic changes in type A chronic atrophic gastritis indicating increased risk of neuroendocrine tumor development: the predictive role of dysplastic and severely hyperplastic enterochromaffin-like cell lesions. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1827-1837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Poveda JC, Chahar S, Garcia-Buitrago MT, Montgomery EA, McDonald OG. The Morphologic Spectrum of Gastric Type 1 Enterochromaffin-Like Cell Neuroendocrine Tumors. Mod Pathol. 2023;36:100098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | De Block CE, De Leeuw IH, Bogers JJ, Pelckmans PA, Ieven MM, Van Marck EA, Van Acker KL, Van Gaal LF. Autoimmune gastropathy in type 1 diabetic patients with parietal cell antibodies: histological and clinical findings. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:82-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Berna MJ, Annibale B, Marignani M, Luong TV, Corleto V, Pace A, Ito T, Liewehr D, Venzon DJ, Delle Fave G, Bordi C, Jensen RT. A prospective study of gastric carcinoids and enterochromaffin-like cell changes in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: identification of risk factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1582-1591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | La Rosa S, Vanoli A. Gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms and related precursor lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:938-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rugge M, Bricca L, Guzzinati S, Sacchi D, Pizzi M, Savarino E, Farinati F, Zorzi M, Fassan M, Dei Tos AP, Malfertheiner P, Genta RM, Graham DY. Autoimmune gastritis: long-term natural history in naïve Helicobacter pylori-negative patients. Gut. 2023;72:30-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Wang X, Jiao J, Huh WJ, Zhang X. Histopathologic Progression of Autoimmune Atrophic Gastritis: A Retrospective Review of 180 Specimens From 32 Patients. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2025;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/