Published online Dec 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i48.114786

Revised: October 28, 2025

Accepted: November 12, 2025

Published online: December 28, 2025

Processing time: 90 Days and 10.1 Hours

This editorial critically analyses the recent article by Jung et al, which investigates the utility of 4-hour serum amylase and lipase as early blood markers for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) acute pancreatitis prediction. Although these enzymes are valuable for the early diagnosis of post-ERCP pancreatitis, they lack specificity for disease etiology and provide limited insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying disease progression. Several cytokines, notably interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and IL-8, are increased in post-ERCP pancreatitis and may serve as potential predictors for disease severity. The incorporation of these biomarkers in early enzymatic bio

Core Tip: Although high serum 4-hour amylase and lipase levels enable early diagnosis of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis, they have limited prognostic value and lack etiological specificity. Interleukin (IL)-6 has emerged as an early inflammatory biomarker for predicting post-ERCP pancreatitis severity. However, detection and quantification of this cytokine remain costly. Validation of rapid, cost-effective, and point-of-care IL-6 immunoassays is essential for their inte

- Citation: Bouayad A. Harnessing early enzymatic biomarkers and cytokines for risk prediction in post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(48): 114786

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i48/114786.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i48.114786

Acute post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis is an inflammatory condition of the pancreas characterized by premature intrapancreatic activation of zymogens[1] and dysregulation of inflammatory mediators[2,3]. It occurs in approximately 10% of unselected cases and up to 14% of high-risk patients, with severe dis

The diagnosis of patients with post-ERCP pancreatitis is established based on acute abdominal pain, elevated amylase or lipase levels exceeding three times the upper limit of normal (ULN), and imaging findings, as no single gold-standard test currently exists[5,6]. Abdominal pain is mediated by several pathways, including local pancreatic inflammation, neurogenic sensitization, and ductal or vascular injury[2]. Elevated serum amylase and lipase reflect pancreatic acinar cell injury, premature zymogen activation, and subsequent release of enzymes into the blood during the inflammatory response[2].

Recent research, including the work of Jung et al[7], suggests the utility of 4-hour serum amylase and lipase as biomarkers for the early prediction of post-ERCP pancreatitis. While valuable for early diagnosis, these enzymes lack specificity for disease etiology and provide limited insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying disease severity. Furthermore, the onset and progression of post-ERCP pancreatitis are highly variable among patients, highlighting the need to develop inflammatory biomarkers to assess the diverse aspects of this disease. Among these markers, several cytokines and chemokines appear to predict prognosis in this condition[8]. The integration of these inflammatory markers in early enzymatic biomarkers and established prognostic scoring systems could further enhance their accuracy and allow for earlier, more effective management of post-ERCP pancreatitis patients.

Numerous investigations have evaluated the predictive efficacy of 4-hour post-ERCP amylase and lipase levels, although the timing of analysis, the selected cut-off values, and analytical methods have varied[7,9-12].

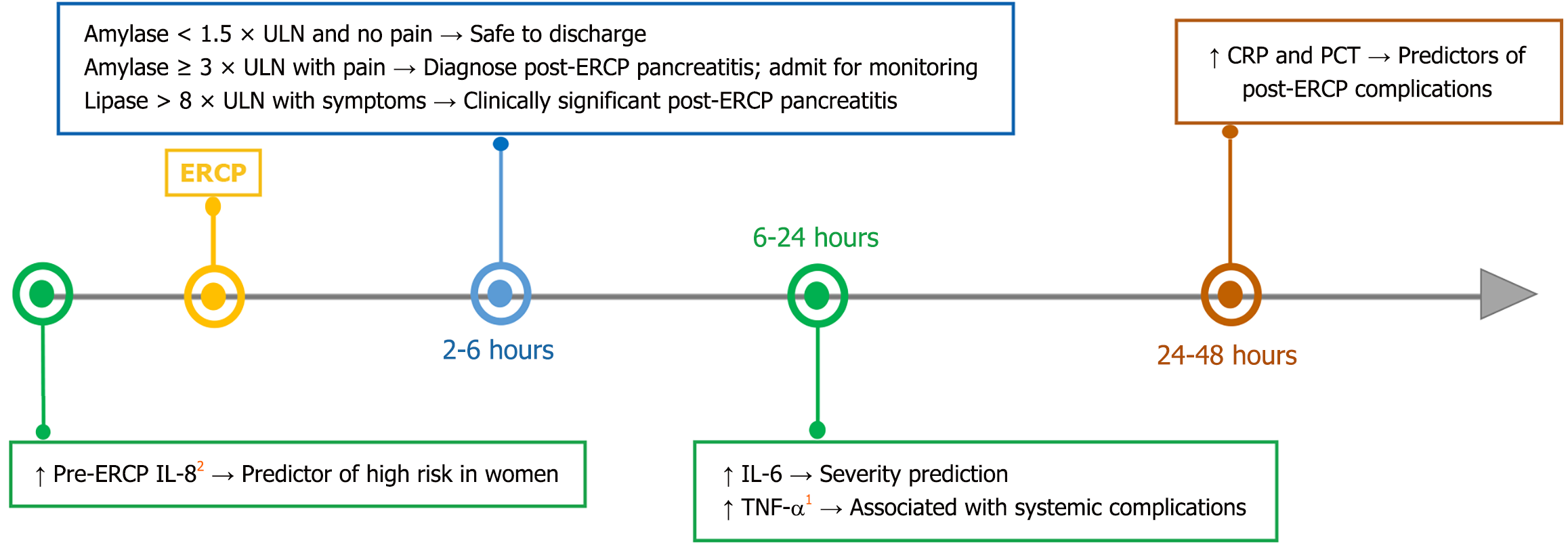

Various methods have been used to select optimal post-ERCP amylase or lipase cut-off values, including Youden’s J statistic[7] and positive/negative likelihood ratios[10]. However, determining the optimal cut-offs for admission or discharge after ERCP remains challenging, with considerable variability across studies. A recent meta-analysis suggested that serum amylase or lipase > 3 × ULN measured 2-4 hours post-ERCP has utility for predicting post-ERCP pancreatitis[13]. Thomas and Sengupta[9] proposed a practical 4-hour algorithm, showing that an amylase level < 1.5 × ULN safely excluded post-ERCP pancreatitis (sensitivity 100%), while a level ≥ 3 × ULN was suggested to help target early intervention or preventive measures (specificity 95.3%). Sutton et al[10] confirmed that a 4-hour amylase level > 2.5 × ULN with pancreatogram and > 5 × ULN without pancreatogram predicts post-ERCP pancreatitis with balanced accuracy. Lee et al[11] identified 4-hour post-ERCP amylase level > 4 × ULN, lipase level > 8 × ULN, precut sphincterotomy, and pancreatic sphincterotomy as significant predictors of post-ERCP pancreatitis. More recently, Jung et al[7] demonstrated strong diagnostic performance of both 4-hour and 24-hour enzyme measurements, with superior area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) at 24 hours but greater clinical practicality at 4 hours. Furthermore, these cut-off values are context-dependent, varying according to patient-specific risk factors such as female sex, younger age, naive papilla, surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy, and procedural complexity, underscoring the need for personalized risk stratification[6,7,9-11]. These results support a dual-threshold approach, in which higher cut-offs improve specificity for admission decisions, whereas lower cut-offs maximize sensitivity for safe discharge, highlighting the lack of a universal gold standard (Figure 1).

In addition to post-ERCP pancreatitis, mild elevations of lipase may occur in various disorders. These include intra-abdominal pancreatic and non-pancreatic disorders[14,15], renal impairment[16], macro-lipase formation[17], diabetes[18], and certain medications[19]. Moreover, 39% of patients with post-ERCP pancreatitis did not show persistent abdominal pain or elevated amylase levels, indicating that imaging is essential to confirm the diagnosis in patients with atypical presentations[6].

Finally, biochemical lipase assays can be difficult to perform and are sometimes subject to various interferences, which may lead to falsely raised values of serum lipase. Notably, high triglyceride levels can competitively interfere with the lipase assay, producing false results[12]. However, this effect can be reduced by using lipid-clearing agents and by performing lipase and lipid profile measurements on separate biochemical instruments.

Taken together, current evidence supports 4-hour post-ERCP enzyme measurement as the most practical strategy in outpatient settings, balancing diagnostic accuracy, feasibility, and patient safety.

Adequate assessment of post-ERCP pancreatitis severity is necessary to predict prognosis and compare the efficacy of prophylactic measures for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Jung et al[7] reported that 4-hour serum amylase and lipase poorly predict early post-ERCP pancreatitis severity, and associations with cytokine levels were not evaluated. Several clinical and biological scoring systems, as well as computed tomography-based criteria, have been proposed to predict severity[20-23]. However, these approaches are often limited by either the inability to obtain a complete score until at least 48 hours after onset or the complexity of the scoring system itself.

Several studies have investigated cytokine and chemokine levels as early inflammatory biomarkers in post-ERCP pancreatitis. A wide variety of cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and IL-8, were found to be good early biomarkers for predicting the severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis within the first 24 hours after pancreatic injury[24-26] (Table 1). However, Concepción-Martín et al[26] demonstrated that these cytokines were not associated with the occurrence of post-ERCP pancreatitis 4 hours after the procedure.

| Cytokine | Cytokine type | Clinical utility | Detection method | Assay limitations |

| IL-6 | Pro- and anti-inflammatory | (1) Peaks 12-24 hours post-ERCP in severe cases[24,29]; (2) Peaks within 6-24 hours, earlier than CRP and PCT[27,28]; and (3) Cut-off 196.6 pg/mL in SAP. Sensitivity 81.8%, specificity 91.3%, and AUC = 0.882[30] | Chemiluminescence[26,32]; ELISA[24,29] | High cost |

| TNF-α | Pro-inflammatory | (1) Elevated at 12 hours in patients with complicated post-ERCP pancreatitis[29]; and (2) Cut-off 0.07 pg/mL in SAP. Sensitivity 63.6%, specificity 61.8%, and AUC = 0.562[30] | ELISA[29,43] | Labor-intensive and time-consuming |

| IL-8 | Pro-inflammatory chemokine | (1) Early predictor of pre-ERCP pancreatitis development[32]; and (2) Cut-off 1.46 pg/mL in SAP. Sensitivity 72.7%, specificity 73.1%, and AUC = 0.700[30] | Chemiluminescence[32]; ELISA[43] | High cost |

| IL-10 | Anti-inflammatory | (1) Associated with ERCP-related factors[28]; (2) Conflicting results regarding preventive potential in post-ERCP pancreatitis after IL-10 administration[35,36]; (3) Potential predictor of treatment response[42]; and (4) Cut-off 9.54 pg/mL in SAP. Sensitivity 72.7%, specificity 93.3%, and AUC = 0.762[30] | ELISA[28,43] | Labor-intensive and time-consuming |

IL-6 is considered the main cytokine involved in the inflammation associated with post-ERCP pancreatitis. After ERCP, IL-6 levels can rise rapidly and peak within 6-24 hours, earlier than C-reactive protein and procalcitonin[27,28]. Several studies have confirmed the role of IL-6 as an early biomarker for predicting the severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis[24,29]. Serum IL-6 concentrations are significantly elevated in severe post-ERCP pancreatitis at 12-24 hours post-procedure, supporting its utility for early severity stratification[24,29]. Results based on cut-off values for predicting severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) indicate that IL-6 performs best with a cut-off value of 196.6 pg/mL, yielding a sensitivity of 81.8%, a specificity of 91.3%, and an AUC of 0.882[30] (Table 1). The performance of this cytokine in predicting SAP at 24 hours is acceptable yet suboptimal, with a sensitivity of 79.8%, a specificity of 74.7%, and an AUC of 0.75[31]. Further studies are needed to confirm the diagnostic accuracy of IL-6 in predicting severe post-ERCP pancreatitis. Although more informative, quantitative measurement of IL-6 in post-ERCP pancreatitis studies using enzyme chemiluminescence[26,32] and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay[24,29] remains laborious and costly. Therefore, the development and validation of rapid, cost-effective, and point-of-care cytokine immunoassays using lateral flow colorimetric methods[33] are essential for routine clinical use in post-ERCP pancreatitis risk prediction.

TNF-α is a proinflammatory cytokine that has been investigated as a potential biomarker in post-ERCP pancreatitis. Kilciler et al[29] reported elevated serum TNF-α levels in patients with complicated post-ERCP pancreatitis at 12 hours post-admission. The diagnostic accuracy of TNF-α for predicting SAP, based on a cut-off value of 0.07 pg/mL, was low, with a sensitivity of 63.6%, a specificity of 61.8%, and an AUC of 0.562[30], limiting its clinical utility. While TNF-α shows promise, its routine clinical utility is constrained by high assay cost, the short circulating half-life of TNF-α, considerable biological and analytical variability, and the limited availability of standardized assays[34].

IL-8 is the most well-characterized pro-inflammatory CXC chemokine studied in post-ERCP pancreatitis and acts as a potent secondary chemoattractant for neutrophils during the inflammatory response. A recent study of adult patients at high risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis showed that elevated pre-ERCP serum IL-8 levels were associated with the development of post-ERCP pancreatitis[32]. Thus, the ability to measure IL-8 levels in serum could be a useful marker for predicting post-ERCP pancreatitis, particularly in younger female patients. The level of IL-8 demonstrated a suboptimal predictive value for SAP based on a cut-off value of 1.46 pg/mL, with a sensitivity of 79.8%, a specificity of 74.7%, and an AUC of 0.75[30] (Table 1). This pro-inflammatory chemokine also appears to have a suboptimal diagnostic value for SAP at 24 hours, with an AUC of 0.73[31]. However, its clinical utility in post-ERCP pancreatitis remains limited by assay variability and high cost.

IL-10, a key anti-inflammatory cytokine, can downregulate the production of proinflammatory mediators and modulate immune responses. An IL-10 cut-off value of 9.54 pg/mL demonstrated a sensitivity of 72.7% and a high specificity of 93.3% for SAP, with an AUC of 0.762[30] (Table 1). Although IL-10 has been associated with ERCP-related factors such as pain score, degree of ampullary irritation, and ERCP duration, its utility as a biomarker of post-ERCP pancreatitis severity has not been established[28]. Evidence regarding its preventive potential in post-ERCP pancreatitis remains conflicting. In a randomized double-blind study, Devière et al[35] showed a reduced incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis after IL-10 administration, although this was not supported in the study by Dumot et al[36]. Furthermore, the therapeutic efficacy of IL-10-based drugs is restricted by the complex pleiotropic properties of IL-10, which can occasionally result in opposing physiological effects[37]. Additionally, inexpensive and effective prophylactic strategies, such as rectal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and pancreatic stent placement, have further limited its clinical use in patients at high risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis[38-41]. Interestingly, a recent experimental study reported that Gegen Qinglian decoction, a traditional Chinese medicine formula, increased IL-10 release while reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18, thereby preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis progression in rats[42]. Additional studies accounting for confounding variables may help clarify the role of IL-10 in post-ERCP pancreatitis and its value as a predictor of treatment response.

Taken together, cytokine measurements represent a useful early biomarker for predicting post-ERCP pancreatitis severity. However, large-scale prospective studies are needed to differentiate cytokine profiles between mild and severe cases and to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of early cytokine testing compared with standard observation protocols.

Measurement of amylase and lipase levels 4 hours post-ERCP can guide early admission or intensive monitoring, particularly in centers with limited resources (Figure 1). IL-6 can help predict the severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis and identify patients at the highest risk who could benefit from intensified prophylactic strategies, while potentially reducing unnecessary stent placements in low-risk individuals. Thus, a potential diagnostic approach post-ERCP begins with clinical evaluation, followed by early assessment using 4-hour post-ERCP lipase and amylase levels. Based on the results, IL-6 measurement may be performed 12-24 hours post-ERCP in high-risk individuals and integrated with clinical scoring systems such as the acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II (Figure 1). Such an approach could improve the prediction of disease severity and enable effective monitoring of disease progression.

| 1. | Rinderknecht H. Activation of pancreatic zymogens. Normal activation, premature intrapancreatic activation, protective mechanisms against inappropriate activation. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:314-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Akshintala VS, Boparai IS, Barakat MT, Husain SZ. Post Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis: Novel Mechanisms and Prevention by Drugs. United European Gastroenterol J. 2025;13:78-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wen L, Javed TA, Yimlamai D, Mukherjee A, Xiao X, Husain SZ. Transient High Pressure in Pancreatic Ducts Promotes Inflammation and Alters Tight Junctions via Calcineurin Signaling in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1250-1263.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Akshintala VS, Kanthasamy K, Bhullar FA, Sperna Weiland CJ, Kamal A, Kochar B, Gurakar M, Ngamruengphong S, Kumbhari V, Brewer-Gutierrez OI, Kalloo AN, Khashab MA, van Geenen EM, Singh VK. Incidence, severity, and mortality of post-ERCP pancreatitis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 145 randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;98:1-6.e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4722] [Article Influence: 363.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (48)] |

| 6. | Suzuki A, Uno K, Nakase K, Mandai K, Endoh B, Chikugo K, Kawakami T, Suzuki T, Nakai Y, Kusumoto K, Itokawa Y, Inatomi O, Bamba S, Mizumoto Y, Tanaka K. Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis assessed using criteria for acute pancreatitis. JGH Open. 2021;5:1391-1397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jung JH, Lee KJ, Park SW, Park DH, Cha HW, Koh DH, Lee J. Early risk stratification of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis using 4-hour serum amylase and lipase: A prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:111265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Greer PJ, Lee PJ, Paragomi P, Stello K, Phillips A, Hart P, Speake C, Lacy-Hulbert A, Whitcomb DC, Papachristou GI. Severe acute pancreatitis exhibits distinct cytokine signatures and trajectories in humans: a prospective observational study. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2022;323:G428-G438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Thomas PR, Sengupta S. Prediction of pancreatitis following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography by the 4-h post procedure amylase level. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:923-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sutton VR, Hong MK, Thomas PR. Using the 4-hour Post-ERCP amylase level to predict post-ERCP pancreatitis. JOP. 2011;12:372-376. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lee YK, Yang MJ, Kim SS, Noh CK, Cho HJ, Lim SG, Hwang JC, Yoo BM, Kim JH. Prediction of Post-Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis Using 4-Hour Post-Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Serum Amylase and Lipase Levels. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32:1814-1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kumari S, Shekhar R, Kumari R, Prakash P. Study of analytical error in lipase assay. Ann Afr Med. 2023;22:55-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hirota M, Itoi T, Morizane T, Koiwai A, Yasuda I, Ryozawa S, Mukai S, Ikeura T, Irisawa A, Iwasaki E, Katanuma A, Kitamura K, Takenaka M, Ito T, Masamune A, Mayumi T, Takeyama Y. Postprocedure serum amylase or lipase levels predict postendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: Meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies and utility assessment. Dig Endosc. 2024;36:670-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wen WH, Chen HL, Chang MH, Ni YH, Shih HH, Lai HS, Hsu WM. Fecal elastase 1, serum amylase and lipase levels in children with cholestasis. Pancreatology. 2005;5:432-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hameed AM, Lam VW, Pleass HC. Significant elevations of serum lipase not caused by pancreatitis: a systematic review. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17:99-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Masoero G, Bruno M, Gallo L, Colaferro S, Cosseddu D, Vacha GM. Increased serum pancreatic enzymes in uremia: relation with treatment modality and pancreatic involvement. Pancreas. 1996;13:350-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Keating JP, Lowe ME. Persistent hyperlipasemia caused by macrolipase in an adolescent. J Pediatr. 2002;141:129-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Semakula C, Vandewalle CL, Van Schravendijk CF, Sodoyez JC, Schuit FC, Foriers A, Falorni A, Craen M, Decraene P, Pipeleers DG, Gorus FK. Abnormal circulating pancreatic enzyme activities in more than twenty-five percent of recent-onset insulin-dependent diabetic patients: association of hyperlipasemia with high-titer islet cell antibodies. Belgian Diabetes Registry. Pancreas. 1996;12:321-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chao CT, Chao JY. Case report: furosemide and pancreatitis: Importance of dose and latency period before reaction. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:43-45. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Ranson JH, Rifkind KM, Roses DF, Fink SD, Eng K, Spencer FC. Prognostic signs and the role of operative management in acute pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1974;139:69-81. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Blamey SL, Imrie CW, O'Neill J, Gilmour WH, Carter DC. Prognostic factors in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 1984;25:1340-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 484] [Cited by in RCA: 473] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818-829. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Balthazar EJ. Acute pancreatitis: assessment of severity with clinical and CT evaluation. Radiology. 2002;223:603-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 534] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kaw M, Singh S. Serum lipase, C-reactive protein, and interleukin-6 levels in ERCP-induced pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:435-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gunjaca I, Zunic J, Gunjaca M, Kovac Z. Circulating cytokine levels in acute pancreatitis-model of SIRS/CARS can help in the clinical assessment of disease severity. Inflammation. 2012;35:758-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Concepción-Martín M, Gómez-Oliva C, Juanes A, Mora J, Vidal S, Díez X, Torras X, Sainz S, Villanueva C, Farré A, Guarner-Argente C, Guarner C. IL-6, IL-10 and TNFα do not improve early detection of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography acute pancreatitis: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Woźniak B, Wiśniewska-Jarosińska M, Drzewoski J. Evaluation of selected parameters of the inflammatory response to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Pancreas. 2001;23:349-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Oezcueruemez-Porsch M, Kunz D, Hardt PD, Fadgyas T, Kress O, Schulz HU, Schnell-Kretschmer H, Temme H, Westphal S, Luley C, Kloer HU. Diagnostic relevance of interleukin pattern, acute-phase proteins, and procalcitonin in early phase of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1763-1769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kilciler G, Musabak U, Bagci S, Yesilova Z, Tuzun A, Uygun A, Gulsen M, Oren S, Oktenli C, Karaeren N. Do the changes in the serum levels of IL-2, IL-4, TNFalpha, and IL-6 reflect the inflammatory activity in the patients with post-ERCP pancreatitis? Clin Dev Immunol. 2008;2008:481560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sternby H, Hartman H, Thorlacius H, Regnér S. The Initial Course of IL1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α with Regard to Severity Grade in Acute Pancreatitis. Biomolecules. 2021;11:591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Aoun E, Chen J, Reighard D, Gleeson FC, Whitcomb DC, Papachristou GI. Diagnostic accuracy of interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 in predicting severe acute pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2009;9:777-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Machicado JD, Lee PJ, Culp S, Stello K, Hart PA, Ramsey M, Lacy-Hulbert A, Speake C, Cruz-Monserrate Z, Elmunzer BJ, Whitcomb DC, Papachristou GI. Cytokine signatures in post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a pilot study. Ann Gastroenterol. 2024;37:734-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Rahbar M, Wu Y, Subramony JA, Liu G. Sensitive Colorimetric Detection of Interleukin-6 via Lateral Flow Assay Incorporated Silver Amplification Method. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9:778269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Valaperti A, Li Z, Vonow-Eisenring M, Probst-Müller E. Diagnostic methods for the measurement of human TNF-alpha in clinical laboratory. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2020;179:113010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Devière J, Le Moine O, Van Laethem JL, Eisendrath P, Ghilain A, Severs N, Cohard M. Interleukin 10 reduces the incidence of pancreatitis after therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:498-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Dumot JA, Conwell DL, Zuccaro G Jr, Vargo JJ, Shay SS, Easley KA, Ponsky JL. A randomized, double blind study of interleukin 10 for the prevention of ERCP-induced pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2098-2102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Saraiva M, Vieira P, O'Garra A. Biology and therapeutic potential of interleukin-10. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20190418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 745] [Article Influence: 124.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Elmunzer BJ, Scheiman JM, Lehman GA, Chak A, Mosler P, Higgins PD, Hayward RA, Romagnuolo J, Elta GH, Sherman S, Waljee AK, Repaka A, Atkinson MR, Cote GA, Kwon RS, McHenry L, Piraka CR, Wamsteker EJ, Watkins JL, Korsnes SJ, Schmidt SE, Turner SM, Nicholson S, Fogel EL; U. S. Cooperative for Outcomes Research in Endoscopy (USCORE). A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1414-1422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 37.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 39. | Dumonceau JM, Andriulli A, Elmunzer BJ, Mariani A, Meister T, Deviere J, Marek T, Baron TH, Hassan C, Testoni PA, Kapral C; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - updated June 2014. Endoscopy. 2014;46:799-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 420] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Sugimoto M, Takagi T, Suzuki R, Konno N, Asama H, Sato Y, Irie H, Watanabe K, Nakamura J, Kikuchi H, Waragai Y, Takasumi M, Hikichi T, Ohira H. Pancreatic stents for the prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis should be inserted up to the pancreatic body or tail. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2392-2399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Thiruvengadam NR, Saumoy M, Schneider Y, Attala S, Triggs J, Lee P, Kochman ML. A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis for Post-Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis Prophylaxis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:216-226.e42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Cui Y, Li J, Cai M, Zhang Y, Zhao B, Liu J. Gegen Qinlian decoction prevents post-ERCP pancreatitis by regulating NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1588585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Chen CC, Wang SS, Lu RH, Lu CC, Chang FY, Lee SD. Early changes of serum proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Pancreas. 2003;26:375-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/