Published online Dec 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.113060

Revised: September 16, 2025

Accepted: October 23, 2025

Published online: December 7, 2025

Processing time: 111 Days and 17.7 Hours

Refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) constitutes a significant proportion of GERD cases and presents a considerable burden in clinical practice. However, the underlying risk factors contributing to persistent and refractory symptoms and the clinical characteristics of this disease remain poorly under

To investigate the clinical features of refractory GERD and identify the associated risk factors.

This is a multicenter cross-sectional study on patients with GERD across 18 medical centers in Shanghai. All participants completed comprehensive questionnaires that assessed their demographic characteristics, lifestyle and dietary habits, clinical manifestations, somatic symptoms, mental and psychological health sta

Our study included 911 patients diagnosed with GERD, of whom 256 (28.1%) had refractory GERD and 655 (71.9%) had non-refractory GERD. Compared to patients with non-refractory GERD, those with refractory GERD are older, have a longer disease duration, and exhibit higher scores for typical reflux symptoms. They are also more likely to present with atypical symptoms, more prone to overeating, more likely to experience somatic symptoms, comorbid anxiety, and depression, and report a lower quality of life. Binary logistic regression analysis identified disease duration and anxiety as significant risk factors and at least 90 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week as a protective factor for refractory GERD.

Refractory GERD is associated with a prolonged disease duration, anxiety status, and insufficient physical activity. These findings may afford valuable insights for the clinical management and development of non-pharmacological interventions for refractory GERD.

Core Tip: Refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) represents a clinically challenging subtype of GERD that remains poorly understood. This cross-sectional study examined data from 256 patients with refractory GERD and 655 patients with non-refractory GERD to identify clinical characteristics and potential risk factors. The results indicate that prolonged disease duration, anxiety, and insufficient physical activity are independent risk factors for refractory GERD. Furthermore, age, overeating, esophageal chest pain, sensation of pharyngeal obstruction, and constipation showed strong correlations with refractory GERD. These findings underscore the presence of distinct, complex pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical features in refractory GERD, along with the role of psychological factors, providing useful insights for long-term management and treatment strategies for refractory GERD.

- Citation: Zhang N, Wang Y, Fang SS, Han M, Zheng QW, Zhu YY, Zhang MY, Li JJ, Cui LX, Tian JL, Deng YH, Zhu SL, Ni HM, Zhou L, Zuo GL, Huang TS, Liao Q, Li XQ, Shang YY, Wang YJ, Tian Y, Ge LY, Han HQ, Hu WM, Jiang Y, Li YJ, Mao X, Yang LH, Yao JM, Zheng X, Wang HW, Fang SQ. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease: A multicenter cross-sectional study. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(45): 113060

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i45/113060.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.113060

Refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a heterogeneous condition characterized by an inadequate or suboptimal response to standard acid-suppressive pharmacotherapy. According to the United Nations, over one billion people worldwide were affected by GERD in 2022[1], and refractory GERD accounted for an estimated 13.2%-54.1% of these cases[2-4].

Unlike patients with GERD who typically respond well to acid-suppressing medications, individuals with refractory GERD experience dual burdens of physical discomfort and psychological distress. Research indicates that these patients have significantly increased rates of visits to primary care providers and emergency departments, and their work performance and sleep quality are markedly impaired[5,6]. Furthermore, the need for repeated medical consultations contributes to a substantial economic burden. Patients with refractory GERD incur medical expenses that are, on average, 7000-10000 United States dollars higher than those who respond effectively to the proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy[7,8]. The persistent nature of reflux-related symptoms, combined with the potential adverse effects of prolonged acid suppression, not only compromises the mental health and overall quality of life of patients but may also increase their risk of malignant transformation of the esophageal mucosa[9].

As the number of patients diagnosed with refractory GERD is rising[4], their clinical management is also becoming increasingly challenging, especially in primary care settings such as communities. As a result, researchers have begun to explore possible influencing factors and underlying mechanisms associated with this disease. Existing evidence suggests that lifestyle and dietary habits not only act as significant triggers for GERD symptoms[10,11] but are also closely related to the persistent and recurrent refractory GERD symptoms and poor response to the PPI treatment[12]. Additionally, psychological distress has been identified as a key factor associated with the development of refractory GERD[13,14].

Although the existing literature reports some valuable information on the relationship between refractory GERD and risk factors, there are still major limitations. Specifically, many previous studies have primarily focused on comparing risk factor profiles between different GERD subtypes, particularly between reflux esophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease (NERD)[15], or on contrasting characteristics between patients with GERD and healthy individuals[11]. Some other studies have examined only factors influencing residual symptoms, specifically in patients with NERD[12]. Very few studies are available on refractory GERD. In addition, no cross-sectional investigations on the relationship between refractory and non-refractory GERD are yet available.

This study aims to further investigate the lifestyle habits, dietary habits, clinical manifestations, and psychological status of refractory GERD through a cross-sectional examination at 18 medical centers across Shanghai, China, and identify the independent risk factors of refractory GERD to enhance the awareness of clinicians on refractory GERD.

From December 2023 to June 2024, outpatients aged 18-80 years diagnosed with GERD were consecutively recruited from 7 municipal or district hospitals and 11 community health service centers in Shanghai. All patients were required to meet at least one of the following criteria before enrollment: Presence of typical clinical manifestations within the past month, including heartburn, esophageal chest pain, and regurgitation; Their reflux diagnostic questionnaire score should be ≥ 12[16], and presence of endoscopic esophageal inflammation (Los Angeles grades B/C/D esophagitis) or pathological gastroesophageal reflux as demonstrated by 24-hour potential of hydrogen-impedance monitoring[17] (acid exposure time ≥ 6% and/or increased number of reflux episodes). Refractory GERD was diagnosed in accordance with the consensus criteria established by European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility/American Society of Neuro

All participants were informed of the study details. They voluntarily agreed to participate and signed an informed consent form. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Yueyang Hospital of In

All the outpatient physicians who collected the information underwent a standardized training provided by us. We informed the patients about the purpose and procedures of the survey and conducted face-to-face questionnaire interviews. Patients who agreed to participate completed the questionnaires on-site, which were then immediately collected. The questionnaire was composed of four sections. The first section collected demographic information, including age, gender, height, weight, and marital status. The second section focused on lifestyle and dietary habits. The third section assessed clinical symptom characteristics, including both typical and atypical symptoms. The fourth section evaluated somatic symptoms, psychological status, and quality of life.

The lifestyle questionnaire comprises 10 items assessing the following habits: Staying up late (falling asleep after 2:00), early awakening (waking up more than 30 minutes earlier than usual), frequent dreaming, exercise (engaging in at least 90 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week), smoking (consumption of one or more cigarettes per day for at least one year), and drinking (at least once per week in the past year, with each occasion involving more than 25 g of alcohol for men and more than 15 g for women). The eating habits questionnaire includes 12 items: Eating beyond fullness (habitual eating despite feeling full), skipping breakfast (occurring at least twice per week), and eating before bedtime (within two hours of sleep). Dietary preferences were defined as consuming a specific food type at least three times per week for ≥ 1 year. These included sweet foods (e.g., cakes, cream, and glutinous rice products), greasy foods, raw or cold foods, spicy foods, sour foods (e.g., rice vinegar, citrus fruits, and juices), hot foods (above 65 °C), strong tea (e.g., dark tea with a bitter taste), chocolate, coffee, carbonated beverages, and dairy products.

Typical symptoms of GERD include heartburn, esophageal chest pain, and regurgitation. The severity of each symptom experienced in the past month was assessed using the following scale: 0 (no symptoms), 2 (mild symptoms occasional, occurring approximately once per week), 4 (moderate symptoms intermediate in severity, occurring 2-3 times per week), and 6 (severe symptoms significantly affecting normal daily activities or sleep, occurring 4-7 times per week). Atypical symptoms included nausea, belching, sensation of pharyngeal obstruction, dryness or soreness of the throat, cough, epigastric pain or burning, abdominal distension, poor appetite, constipation, and loose stools. The occurrence of atypical symptoms was evaluated as occurring at least once a week in the past month.

Somatic symptom scale-China: It is a self-report questionnaire developed based on the Shanghai population[19,20]. It has good reliability and validity. This scale consists of 20 brief items and assesses the extent to which patients are bothered by the aforementioned issues over the past six months since they first felt unwell. A score of 36 is the cutoff point for positivity, and a total score of ≥ 36 is considered indicative of the somatic symptom disorder, with higher scores in

Hospital anxiety and depression scale: This scale comprises two parts: The hospital anxiety and depression scale-anxiety (HADS-A) and the hospital anxiety and depression scale-depression (HADS-D)[13,21]. A total score of 0-7 is considered normal, 8-10 indicates mild anxiety/depression, 11-14 indicates moderate anxiety/depression, and 15-21 indicates severe anxiety/depression.

GERD health-related quality of life: This scale includes 10 items focusing on heartburn, swallowing, and medication efficacy over the past month[22,23]. It has fewer items and exhibits a higher response rate than those exhibited by the somatic symptom scale-China (SSS-CN) and HADS. The total score ranges from 0 to 50 points, with higher scores indicating a poorer quality of life.

36-Item short form survey: This survey comprises nine aspects: Physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health perception, vitality, social functioning, emotional well-being, mental health, and health perception[24,25]. Higher scores indicate a better quality of life.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 27 (IBM). Descriptive analysis of continuous variables was conducted using mean ± SD and median (interquartile range), while categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate normality/non-normality. Univariate analysis was used to compare differences between refractory GERD and non-refractory GERD. Student’s t-test was applied for continuous variables with a normal distribution, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normal distribution; the χ2 test was utilized for categorical variables. Variables with a P value of less than 0.1 in the univariate logistic regression analysis were subsequently included in a multivariate binary logistic regression model for further evaluation. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

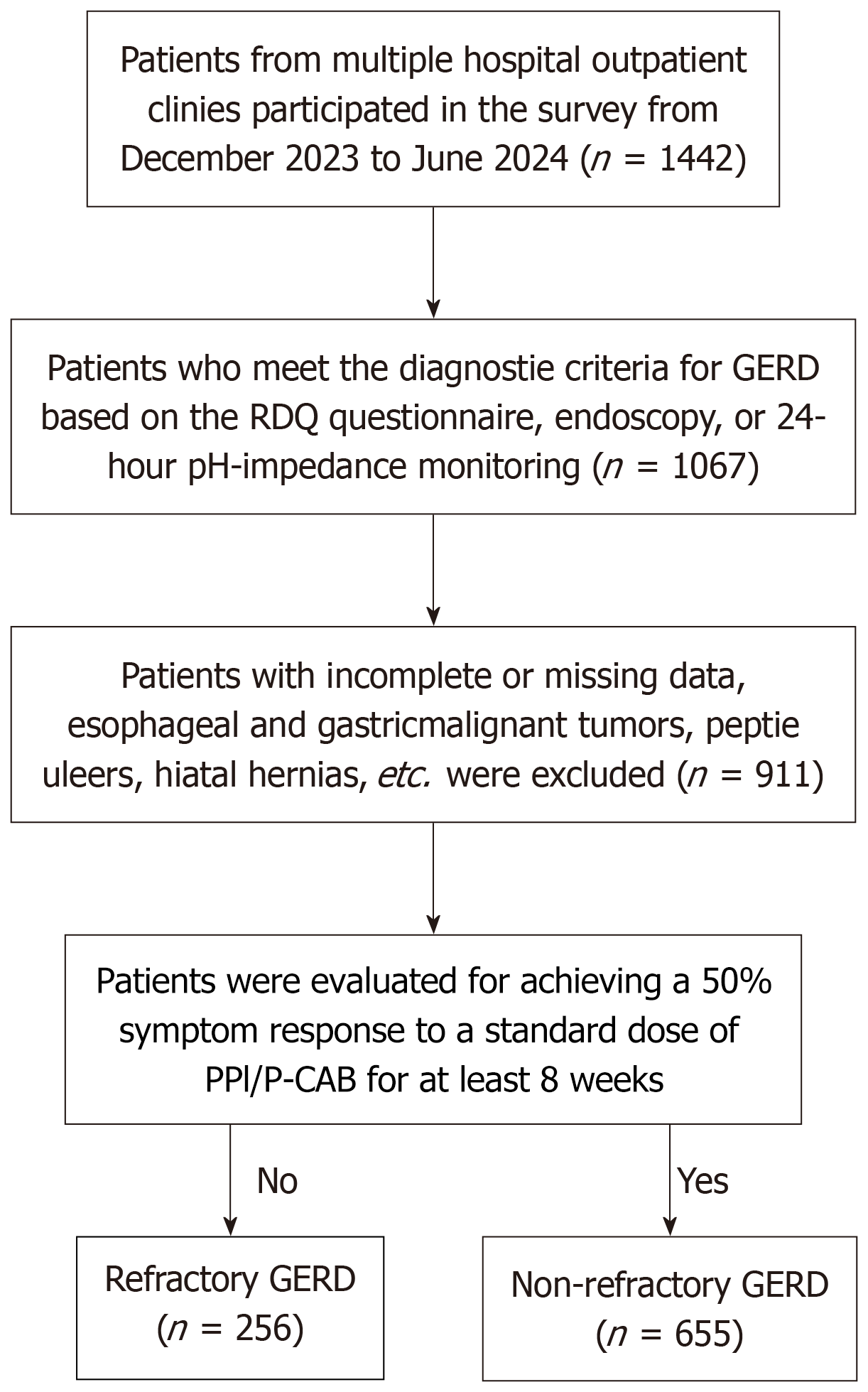

Enrollment and group designation are summarized in Figure 1. The baseline demographic characteristics of refractory GERD and non-refractory GERD groups are presented in Table 1. A total of 911 patients with GERD were enrolled, of whom 256 (28.1%) had refractory GERD and 655 (71.9%) had non-refractory GERD. The proportion of female patients was found to be higher in the overall GERD population. The average age of patients with refractory GERD was significantly higher than that of patients with non-refractory GERD (54.79 ± 12.52 vs 52.54 ± 11.94, P < 0.05). Additionally, patients with refractory GERD had a longer mean disease duration (4.12 ± 3.46 vs 3.05 ± 3.01, P < 0.001). No significant differences in gender or body mass index were observed.

A comparison of clinical manifestation characteristics, including both typical and atypical symptoms, of the two population groups is shown in Table 2. The esophageal chest pain score was significantly higher in patients with refractory GERD than it was in those with non-refractory GERD. However, no significant difference was found regarding heartburn and regurgitation between the two groups. Our study also found that patients with refractory GERD were more likely to experience atypical symptoms such as a sensation of pharyngeal obstruction and constipation. No significant differences were found regarding the prevalence of nausea, belching, sensation of pharyngeal obstruction, dryness or soreness of the throat, cough, epigastric pain or burning, abdominal distension, poor appetite, or diarrhea between the two groups. Furthermore, an analysis of the number of atypical symptoms revealed that patients with refractory GERD experience a greater burden of atypical symptoms (4.22 ± 2.18 vs 3.77 ± 2.08, P = 0.004).

| Symptom | Refractory GERD (n = 256) | Non-refractory GERD (n = 655) | z/χ2 value | P value |

| Typical symptoms | ||||

| Heartburn, median IQR | 2 (2.0, 4.0) | 2 (0.0, 4.0) | -1.388 | 0.165 |

| Regurgitation, median IQR | 2 (2.0, 4.0) | 2 (2.0, 4.0) | -0.55 | 0.582 |

| Esophageal chest pain, median IQR | 2 (0.0, 2.0) | 0 (0.0, 2.0) | -2.543 | 0.011a |

| Atypical symptoms | ||||

| Nausea | 102 (39.84) | 226 (34.50) | 2.278 | 0.131 |

| Belching | 150 (58.59) | 360 (54.96) | 0.985 | 0.321 |

| Sensation of pharyngeal obstruction | 101 (39.45) | 199 (30.38) | 6.858 | 0.009b |

| Dryness or soreness of the throat | 105 (41.02) | 245 (37.40) | 1.014 | 0.314 |

| Cough | 109 (42.58) | 243 (37.10) | 2.33 | 0.127 |

| Epigastric pain or burning | 109 (42.58) | 254 (38.78) | 1.109 | 0.292 |

| Abdominal distension | 130 (50.78) | 319 (48.70) | 0.318 | 0.573 |

| Poor appetite | 124 (48.44) | 284 (43.36) | 1.92 | 0.166 |

| Constipation | 113 (44.14) | 239 (36.49) | 4.546 | 0.033a |

| Diarrhea | 37 (14.45) | 99 (15.11) | 0.063 | 0.801 |

| Number of atypical symptoms | 4.22 ± 2.18 | 3.77 ± 2.08 | 2.901 | 0.004c |

A χ2 test was performed to analyze the lifestyle and dietary habits of patients with refractory GERD and those with non-refractory GERD (Table 3). Compared to patients with non-refractory GERD, those with refractory GERD were more likely to have a dietary habit of overeating (14.84 vs 9.62, P = 0.024). In contrast, a significantly higher proportion of patients in the non-refractory GERD group maintained a lifestyle involving at least 90 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week (26.41 vs 15.63, P = 0.001). Notably, the two groups did not show any significant differences in terms of skipping breakfast, eating before bedtime, picky eating (including sweet foods, greasy foods, raw or cold foods, spicy foods, sour foods, hot foods, strong tea, chocolate, coffee, carbonated beverages, and dairy products), drinking, smoking, staying up late, insomnia, waking up early, or frequent dreaming.

| Factors | Refractory GERD (n = 256) | Non-refractory GERD (n = 655) | χ2 value | P value |

| Dietary habits | ||||

| Eating beyond fullness | 38 (14.84) | 63 (9.62) | 5.098 | 0.024a |

| Skipping breakfast | 29 (11.33) | 75 (11.45) | 0.003 | 0.958 |

| Eating before bedtime | 35 (13.67) | 100 (15.27) | 0.371 | 0.542 |

| Sweet food | 60 (23.44) | 149 (22.75) | 0.049 | 0.824 |

| Greasy food | 54 (21.09) | 134 (20.46) | 0.045 | 0.831 |

| Raw or cold foods | 18 (7.03) | 63 (9.62) | 1.521 | 0.218 |

| Spicy foods | 69 (26.95) | 151 (23.05) | 1.528 | 0.216 |

| Sour foods | 25 (9.77) | 49 (7.48) | 1.287 | 0.257 |

| Hot foods | 37 (14.45) | 84 (12.82) | 0.424 | 0.515 |

| Strong tea | 41 (16.02) | 101 (15.42) | 0.05 | 0.824 |

| Chocolate | 23 (8.98) | 69 (10.53) | 0.487 | 0.485 |

| Coffee | 56 (21.88) | 141 (21.53) | 0.013 | 0.909 |

| Carbonated beverages | 31 (12.11) | 75 (11.45) | 0.078 | 0.780 |

| Dairy products | 57 (22.27) | 165 (25.19) | 0.855 | 0.355 |

| Lifestyle habits | ||||

| Smoking | 23 (8.98) | 80 (12.21) | 1.914 | 0.166 |

| Drinking | 47 (18.36) | 120 (18.32) | 0.001 | 0.989 |

| Staying up late | 37 (14.45) | 129 (19.69) | 3.394 | 0.065 |

| Early awakening | 44 (17.19) | 128 (19.54) | 0.666 | 0.414 |

| Frequent dreaming | 49 (19.14) | 94 (14.35) | 3.191 | 0.074 |

| Exercise | 40 (15.63) | 173 (26.41) | 11.956 | 0.001b |

Our study compared the somatization symptoms, mental and psychological status, and quality of life of the two groups of participants (Table 4). A statistically significant difference regarding the SSS-CN score was noted between the two groups (28.85 ± 7.68 vs 27.00 ± 6.91, P < 0.001). Regarding the mental and psychological health status, both the HADS-A score (5.30 ± 3.78 vs 3.76 ± 3.74, P < 0.001) and HADS-D score (6.62 ± 4.07 vs 5.07 ± 4.16, P < 0.001) were significantly higher in the refractory GERD group than they were in the non-refractory GERD group. Additionally, in terms of quality of life, patients with refractory GERD had significantly higher GERD health-related quality of life (GERD-HRQL) scores (11.34 ± 6.76 vs 9.66 ± 6.52, P = 0.001), while there was no significant difference in the 36-Item short form survey (SF-36) scores of the two groups (Table 4). Furthermore, our findings indicated that exercise was significantly associated with esophageal chest pain, as well as with the HADS-A, HADS-D, and GERD-HRQL scores (Table 5). Esophageal chest pain was positively correlated with and the sensation of pharyngeal obstruction and constipation were negatively correlated with the SSS-CN, HADS-A, and HADS-D scores (Table 6). In addition, our study indicates that carbonated beverages were positively correlated with the HADS-A and HADS-D scores, and drinking was positively correlated with the SSS-CN score (Table 7).

| Variable | Refractory GERD (n = 256) | Non-refractory GERD (n = 655) | t value | P value |

| Somatic symptom | ||||

| SSS-CN score | 28.85 ± 7.68 | 27.00 ± 6.91 | 3.512 | < 0.001c |

| Mental and psychological health status | ||||

| HADS-A score | 5.30 ± 3.78 | 3.76 ± 3.74 | 5.551 | < 0.001c |

| HADS-D score | 6.62 ± 4.07 | 5.07 ± 4.16 | 5.075 | < 0.001c |

| Quality of life | ||||

| GERD-HRQL score | 11.34 ± 6.76 | 9.66 ± 6.52 | 3.467 | 0.001b |

| SF-36 score | 114.35 ± 18.70 | 112.64 ± 18.35 | 1.255 | 0.21 |

| Factors | SSS-CN score | HADS-A score | HADS-D score | |||

| r value | P value | r value | P value | r value | P value | |

| Dietary habits | ||||||

| Eating beyond fullness | -0.077 | 0.22 | -0.007 | 0.905 | -0.018 | 0.778 |

| Skipping breakfast | -0.068 | 0.278 | -0.037 | 0.557 | -0.052 | 0.408 |

| Eating before bedtime | -0.089 | 0.154 | -0.104 | 0.097 | -0.11 | 0.078 |

| Sweet food | 0.033 | 0.604 | 0.098 | 0.118 | -0.007 | 0.915 |

| Greasy food | 0.082 | 0.189 | 0.087 | 0.165 | 0.029 | 0.643 |

| Raw or cold foods | -0.063 | 0.315 | 0.050 | 0.423 | 0.012 | 0.852 |

| Spicy foods | -0.035 | 0.580 | -0.015 | 0.816 | 0.008 | 0.901 |

| Sour foods | -0.015 | 0.812 | 0.065 | 0.303 | 0.099 | 0.115 |

| Hot foods | -0.088 | 0.162 | 0.006 | 0.920 | 0.0350 | 0.576 |

| Strong tea | -0.035 | 0.579 | 0.046 | 0.462 | -0.004 | 0.944 |

| Chocolate | -0.033 | 0.601 | 0.076 | 0.227 | 0.122 | 0.052 |

| Coffee | -0.035 | 0.578 | 0.047 | 0.452 | 0.053 | 0.403 |

| Carbonated beverages | 0.115 | 0.067 | 0.185 | 0.003b | 0.207 | 0.001b |

| Dairy products | -0.053 | 0.396 | 0.107 | 0.086 | 0.102 | 0.103 |

| Lifestyle habits | ||||||

| Smoking | 0.015 | 0.808 | -0.033 | 0.600 | -0.026 | 0.676 |

| Drinking | 0.199 | 0.001b | 0.027 | 0.666 | 0.032 | 0.607 |

| Staying up late | -0.057 | 0.362 | 0.001 | 0.995 | -0.020 | 0.755 |

| Early awakening | -0.057 | 0.360 | -0.115 | 0.067 | -0.089 | 0.156 |

| Frequent dreaming | -0.088 | 0.158 | -0.048 | 0.443 | -0.117 | 0.062 |

We performed a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of variables related to refractory GERD (Table 8). Univariate analysis indicated that refractory GERD was associated with age, disease duration, esophageal chest pain, sensation of pharyngeal obstruction, constipation, eating beyond fullness, exercise, and SSS-CN, HADS-A, HADS-D, GERD-HRQL, and SF-36 scores. Multivariate logistic regression analysis, after adjusting for potential confounding variables and conducting multicollinearity analysis, identified disease duration [β = -0.093, odds ratio (OR) = 0.911, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.872-0.953, P < 0.001] and anxiety (β = -0.100, OR = 0.905, 95%CI: 0.869-0.941, P < 0.001) as significant risk factors for refractory GERD. In contrast, engaging in moderate-intensity physical activity for at least 90 minutes per week was identified as a protective factor (β = 0.585, OR = 1.795, 95%CI: 1.215-2.650, P = 0.003).

| Factors | β | SE | Wald | P value | OR | OR (95%CI) |

| Age | -0.009 | 0.006 | 1.784 | 0.182 | 0.991 | 0.979-1.004 |

| Disease duration | -0.089 | 0.023 | 14.943 | < 0.001c | 0.915 | 0.874-0.957 |

| Eating beyond fullness | 0.362 | 0.231 | 2.453 | 0.117 | 1.436 | 0.913-2.260 |

| Exercise | 0.588 | 0.207 | 8.091 | 0.004b | 1.800 | 1.201-2.698 |

| Esophageal chest pain | -0.008 | 0.061 | 0.018 | 0.892 | 0.992 | 0.879-1.118 |

| Sensation of pharyngeal obstruction | 0.232 | 0.171 | 1.833 | 0.176 | 1.261 | 0.901-1.763 |

| Constipation | 0.135 | 0.163 | 0.685 | 0.408 | 1.145 | 0.831-1.576 |

| SSS-CN score | -0.014 | 0.013 | 1.239 | 0.266 | 0.986 | 0.961-1.011 |

| HADS-A score | -0.085 | 0.024 | 13.122 | < 0.001c | 0.918 | 0.877-0.962 |

| GERD-HRQL score | 0.006 | 0.014 | 0.161 | 0.689 | 1.006 | 0.978-1.034 |

Refractory GERD has emerged as a major and challenging clinical issue in the field of gastroenterology in recent years. We herein performed a large-scale, multicenter, cross-sectional survey across multiple hospitals and primary community healthcare centers in Shanghai, China, to investigate the clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with refractory GERD. Existing research suggests that the development of refractory GERD involves multiple complex patho

In our study, the proportion of patients with refractory GERD was 28.1%, which is consistent with the findings of previous prospective studies[26,27]. Age, eating beyond fullness, and clinical symptoms are strongly associated with refractory GERD, suggesting their potential involvement in the pathogenesis of this condition. We found that patients with refractory GERD had a higher age distribution. Numerous prior studies on patients with GERD have demonstrated that both the incidence and overall burden of GERD increase with age, and thus, age is recognized as a significant risk factor[14,28-30]. This trend may be attributed to age-related impairments in anti-reflux mechanisms, such as reduced resting pressure of the upper esophageal sphincter and increased ineffective esophageal motility[31]. However, some studies have reported that age does not significantly influence the severity of esophageal lesions, including changes in esophageal motility and mucosal injury[32,33]. As the disease duration could be an age-related variable, we performed a correlation analysis between age and disease course and found no significant association with refractory GERD.

Compared with patients with non-refractory GERD, those with refractory GERD have higher typical symptom scores of esophageal chest pain and a higher number of atypical symptoms, among which the sensation of pharyngeal obstruction and constipation are the most significant ones. Similar results have been reported by previous studies. It has been previously reported that the non-responsiveness of patients with NERD after taking PPI is related to constipation and that the total symptom score of such patients could significantly decrease after adding prokinetic drugs to their prescription[34]. According to Furuta, the unusual sensation in the throat is a factor impacting the efficacy of rabeprazole (10 mg daily) in patients with GERD[35]. Additionally, studies have shown that patients with refractory GERD with extraesophageal symptoms experience a significant increase in weak acid reflux events[36], which may partially explain why patients with more extraesophageal atypical symptoms cannot benefit from acid-suppressing therapy, further highlighting the involvement of extra-acid mechanisms in this disease. In addition, our findings revealed the esophageal chest pain to be positively correlated with the SSS-CN, HADS-A, and HADS-D scores, whereas the sensation of pha

In terms of lifestyle and dietary habits, patients with refractory GERD are more likely to eat beyond fullness. A recent study indicated that eating beyond fullness is the most frequently reported habit and risk factor among individuals experiencing persistent reflux symptoms[37]. In contrast to previous findings that reported numerous predisposing factors regarding the lifestyle and dietary habits of patients with GERD, our study did not find many positive results in terms of such factors in patients with refractory GERD. Additionally, we considered whether poor living habits and dietary patterns play an indirect role in the development of the condition. We found that carbonated beverages have a positive correlation with HADS-A and HADS-D scores, and drinking has a positive correlation with the SSS-CN score. Previous studies have also reported similar results[38,39], that is, frequent consumption of carbonated beverages is associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression. However, drinking does not aggravate somatization symptoms[40]. Thus, it remains unclear whether these factors contribute to refractory GERD by exacerbating anxiety, depression, and somatization symptoms, which requires further in-depth research. This discrepancy suggests that non-lifestyle and non-dietary factors may exert a more pronounced influence on the manifestation of refractory GERD. We hypothesize that patients with refractory GERD, who often experience long-term symptom recurrence, may be more alert to the behaviors that exacerbate or trigger symptoms. Consequently, they may consciously modify their habits to avoid inducing reflux, which could account for the limited number of significant variables identified in our analysis despite the inclusion of numerous relevant factors.

Our study results indicated that prolonged disease duration is a risk factor for refractory GERD, which is consistent with prior research. Fuchs established a clinical predictive model and reported that the longer the duration of GERD, the higher the frequency of abnormal functional states such as lower esophageal sphincter incompetence and esophageal acid exposure in patients. These disease parameters are causally related to disease progression[41]. However, he did not investigate the relationship between the PPI treatment efficacy and disease duration, nor did he assess the symptom profiles, psychological status, or quality of life of patients. Future studies should incorporate these variables to generate more comprehensive and clinically relevant evidence.

Our study also found that maintaining at least 90 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week is a protective factor against refractory GERD. Mehta conducted a 12-year follow-up study among white women experiencing acid reflux or heartburn at least once weekly and found that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity for at least 30 minutes per day can significantly reduce the risk of GERD symptoms[42]. Furthermore, accumulating more than 150 minutes of physical activity per week is associated with a lower risk of reflux episode occurrence[43,44]. However, the specific mechanism by which exercise alleviates reflux symptoms remains unclear. It may be attributed to the strengthening of the striated muscles of the crural diaphragm through physical activity and the subsequent improvement in the anti-reflux barrier function[10,45]. In refractory GERD, exercise is negatively associated with esophageal chest pain and HADS-A, HADS-D, and GERD-HRQL scores. Research indicates that engaging in brisk walking for 2.5 hours per week may reduce the risk of developing depression by 25%[46]. Exercise can also promote the lactoylation of specific synaptic proteins in the cerebral cortex to alleviate anxiety[47]. These findings suggest that exercise may exert an indirect protective effect, potentially by alleviating anxiety and depression and enhancing the overall quality of life. Thus, regular physical exercise may serve as an effective strategy for reducing the recurrence of reflux symptoms.

Psychological factors have consistently been recognized as significant risk factors for GERD, particularly in cases involving functional esophageal disorders. Patients with GERD often exhibit increased visceral sensitivity, anxiety, depression, and other emotional disturbances[10,48-50]. These psychological conditions may have a bidirectional relationship with GERD, not only elevating the risk of reflux episodes[51] but also directly impacting the quality of life of the patients[52,53]. In this study, after adjusting for confounding variables and conducting a multicollinearity analysis, we identified anxiety as an independent risk factor for refractory GERD, a finding that aligns with previous research. Multiple studies have identified anxiety as a predictive factor for poor response to the PPI therapy[26]. These psychiatric biases can reduce the responsiveness of patients to the PPI treatment[12,13] and increase the frequency of refractory esophageal symptoms[14,54,55]. However, some studies suggest that only higher levels of depression lead to poorer treatment outcomes[56]. In recent years, increasing attention is being given to psychological processes, rather than to physiological parameters, as the primary contributors to symptom severity in patients with refractory GERD[57]. Notably, symptom recurrence in these patients does not appear to be directly linked to reflux events[58], and the role of acid reflux in disease progression has become less prominent. Furthermore, a significant discrepancy exists between the severity of esophageal symptoms and the underlying pathological processes, such as mucosal inflammation or motility disorders. Esophageal hypervigilance and visceral anxiety are considered to be the primary contributing factors[59]. Therefore, investigating the mechanisms linking psychological factors to these conditions may represent an important direction for future research. However, the precise mechanism by which anxiety interacts with this disease remains unclear. It may involve anxiety-induced enhancement of esophageal hyperalgesia and the promotion of central sensitization within the esophagus[60]. Alternatively, it may be associated with the impact of GERD-induced mental disorders on the cerebral cortical structure, potentially mediated through the brain-gut axis by increasing the surface area of the inferior temporal gyrus[61]. Overall, psychological factors appear to contribute to the development of this disease through multiple pathways and perspectives. Psychological disorders such as anxiety not only exacerbate symptoms but also contribute to symptom diversification and complexity.

This cross-sectional study investigated factors associated with refractory GERD. However, the specific mechanisms through which these factors influence the efficacy of PPI, as well as the underlying causes of persistent and recurrent symptoms, remain unclear. Moreover, the causal relationships among these variables have not been definitively established, and the role of genetic factors remains uncertain. Therefore, high-quality prospective studies are needed in the future to develop standardized treatment protocols, establish comparative groups, and dynamically evaluate the impact of lifestyle modifications and risk factor interventions to obtain stronger evidence-based medical evidence. Furthermore, this study was conducted in Shanghai, China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other ethnic and geographic populations. Therefore, larger-scale, multi-regional studies should be conducted in the future.

This study investigated the clinical characteristics and influencing factors of refractory GERD, with a focus on their associations with lifestyle, dietary habits, clinical manifestations, and psychological status. The results demonstrated that refractory GERD is strongly associated with age and the habit of eating beyond fullness behaviors and is more commonly accompanied by atypical symptoms. Notably, our findings identified disease duration and anxiety as independent risk factors and regular physical activity as a protective factor for refractory GERD. The underlying mechanisms linking anxiety to refractory GERD may represent a novel and promising target for therapeutic intervention. These insights are valuable for both physicians and patients, as they facilitate the identification of risk factors and support the development of individualized, comprehensive treatment strategies through lifestyle modifications, psychological counseling, and targeted interventions.

| 1. | Nirwan JS, Hasan SS, Babar ZU, Conway BR, Ghori MU. Global Prevalence and Risk Factors of Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD): Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Kahrilas PJ, Howden CW, Wernersson B, Denison H, Nuevo J, Gisbert JP. Impact of persistent, frequent regurgitation on quality of life in heartburn responders treated with acid suppression: a multinational primary care study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:1005-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chey WD, Mody RR, Izat E. Patient and physician satisfaction with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): are there opportunities for improvement? Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3415-3422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Delshad SD, Almario CV, Chey WD, Spiegel BMR. Prevalence of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Proton Pump Inhibitor-Refractory Symptoms. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1250-1261.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang HM, Huang PY, Yang SC, Wu MK, Tai WC, Chen CH, Yao CC, Lu LS, Chuah SK, Lee YC, Liang CM. Correlation between Psychosomatic Assessment, Heart Rate Variability, and Refractory GERD: A Prospective Study in Patients with Acid Reflux Esophagitis. Life (Basel). 2023;13:1862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Toghanian S, Johnson DA, Stålhammar NO, Zerbib F. Burden of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in patients with persistent and intense symptoms despite proton pump inhibitor therapy: A post hoc analysis of the 2007 national health and wellness survey. Clin Drug Investig. 2011;31:703-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Howden CW, Manuel M, Taylor D, Jariwala-Parikh K, Tkacz J. Estimate of Refractory Reflux Disease in the United States: Economic Burden and Associated Clinical Characteristics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55:842-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Armstrong D, Hungin AP, Kahrilas PJ, Sifrim D, Sinclair P, Vaezi MF, Sharma P. Knowledge gaps in the management of refractory reflux-like symptoms: Healthcare provider survey. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;34:e14387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hao Y, Wang M, Jiang X, Zheng Y, Ran Q, Xu X, Zou B, Wang J, Liu N, Qin B. Non-acid reflux and esophageal dysmotility is associated with early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:8327-8334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sadafi S, Azizi A, Pasdar Y, Shakiba E, Darbandi M. Risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a population-based study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yuan LZ, Yi P, Wang GS, Tan SY, Huang GM, Qi LZ, Jia Y, Wang F. Lifestyle intervention for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a national multicenter survey of lifestyle factor effects on gastroesophageal reflux disease in China. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819877788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Niu XP, Yu BP, Wang YD, Han Z, Liu SF, He CY, Zhang GZ, Wu WC. Risk factors for proton pump inhibitor refractoriness in Chinese patients with non-erosive reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3124-3129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nakada K, Oshio A, Matsuhashi N, Iwakiri K, Kamiya T, Manabe N, Joh T, Higuchi K, Haruma K. Causal effect of anxiety and depression status on the symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease and functional dyspepsia during proton pump inhibitor therapy. Esophagus. 2023;20:309-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu YP, Zhou JX, Wu HB, Wu DP, Qin LZ, Qin B, Xu XY, Yehya SAA, Cheng Y. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of esophageal reflux hypersensitivity: A multicenter study. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:105281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Chen Y, Sun X, Fan W, Yu J, Wang P, Liu D, Song M, Liu S, Zuo X, Zhang R, Hou Y, Han S, Li Y, Zhang J, Li X, Ke M, Fang X. Differences in Dietary and Lifestyle Triggers between Non-Erosive Reflux Disease and Reflux Esophagitis-A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Survey in China. Nutrients. 2023;15:3400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shaw M, Dent J, Beebe T, Junghard O, Wiklund I, Lind T, Johnsson F. The Reflux Disease Questionnaire: a measure for assessment of treatment response in clinical trials. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gyawali CP, Yadlapati R, Fass R, Katzka D, Pandolfino J, Savarino E, Sifrim D, Spechler S, Zerbib F, Fox MR, Bhatia S, de Bortoli N, Cho YK, Cisternas D, Chen CL, Cock C, Hani A, Remes Troche JM, Xiao Y, Vaezi MF, Roman S. Updates to the modern diagnosis of GERD: Lyon consensus 2.0. Gut. 2024;73:361-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 150.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zerbib F, Bredenoord AJ, Fass R, Kahrilas PJ, Roman S, Savarino E, Sifrim D, Vaezi M, Yadlapati R, Gyawali CP. ESNM/ANMS consensus paper: Diagnosis and management of refractory gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33:e14075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jiang M, Zhang W, Su X, Gao C, Chen B, Feng Z, Mao J, Pu J. Identifying and measuring the severity of somatic symptom disorder using the Self-reported Somatic Symptom Scale-China (SSS-CN): a research protocol for a diagnostic study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e024290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wu Y, Tao Z, Qiao Y, Chai Y, Liu Q, Lu Q, Zhou H, Li S, Mao J, Jiang M, Pu J. Prevalence and characteristics of somatic symptom disorder in the elderly in a community-based population: a large-scale cross-sectional study in China. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1334] [Cited by in RCA: 1756] [Article Influence: 76.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Velanovich V. 25 Years of the GERD-HRQL symptom severity instrument: an assessment of published applications. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:255-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pelzner K, Fuchs C, Petersen M, Maus M, Bruns CJ, Leers JM. Sex- and gender-specific differences in symptoms and health-related quality of life among patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 2024;37:doad064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Patel AA, Donegan D, Albert T. The 36-item short form. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:126-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang R, Yan X, Ma XQ, Cao Y, Wallander MA, Johansson S, He J. Burden of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Shanghai, China. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:110-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Heading RC, Mönnikes H, Tholen A, Schmitt H. Prediction of response to PPI therapy and factors influencing treatment outcome in patients with GORD: a prospective pragmatic trial using pantoprazole. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kim SE, Kim N, Oh S, Kim HM, Park MI, Lee DH, Jung HC. Predictive factors of response to proton pump inhibitors in korean patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;21:69-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | GBD 2017 Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:561-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Petrick JL, Nguyen T, Cook MB. Temporal trends of esophageal disorders by age in the Cerner Health Facts database. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:151-154.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Fangxu L, Wenbin L, Pan Z, Dan C, Xi W, Xue X, Jihua S, Qingfeng L, Le X, Songbai Z; Chinese Geriatrics Society. Chinese expert consensus on diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the elderly (2023). Aging Med (Milton). 2024;7:143-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shi HX, Wang ZF, Sun XH. [Characteristics of esophageal motility and clinical presentation in gastroesophageal reflux disease patients of different age groups]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2021;101:1015-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yamasaki T, Hemond C, Eisa M, Ganocy S, Fass R. The Changing Epidemiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Are Patients Getting Younger? J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24:559-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fernandes YR. Unraveling the Dynamics of Esophageal Motility, Esophagitis Severity, and Age in GERD Patients: A Cross-Sectional Exploration. Cureus. 2024;16:e53979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Miyamoto M, Manabe N, Haruma K. Efficacy of the addition of prokinetics for proton pump inhibitor (PPI) resistant non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) patients: significance of frequency scale for the symptom of GERD (FSSG) on decision of treatment strategy. Intern Med. 2010;49:1469-1476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Furuta T, Shimatani T, Sugimoto M, Ishihara S, Fujiwara Y, Kusano M, Koike T, Hongo M, Chiba T, Kinoshita Y; Acid-Related Symptom Research Group. Investigation of pretreatment prediction of proton pump inhibitor (PPI)-resistant patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and the dose escalation challenge of PPIs-TORNADO study: a multicenter prospective study by the Acid-Related Symptom Research Group in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1273-1283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yuan LL, Ji F, Li ZT, Han XW. [Research of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease accompanied by extraesophageal symptom]. Zhonghua Xiaohua Zazhi. 2020;40:45-47. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 37. | Quach DT, Luu MN, Nguyen PV, Vo UP, Vo CH. Dietary and lifestyle factors associated with troublesome gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in Vietnamese adults. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1280511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Narita Z, Hidese S, Kanehara R, Tachimori H, Hori H, Kim Y, Kunugi H, Arima K, Mizukami S, Tanno K, Takanashi N, Yamagishi K, Muraki I, Yasuda N, Saito I, Maruyama K, Yamaji T, Iwasaki M, Inoue M, Tsugane S, Sawada N. Association of sugary drinks, carbonated beverages, vegetable and fruit juices, sweetened and black coffee, and green tea with subsequent depression: A five-year cohort study. Clin Nutr. 2024;43:1395-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Castro A, Gili M, Visser M, Penninx BWJH, Brouwer IA, Montaño JJ, Pérez-Ara MÁ, García-Toro M, Watkins E, Owens M, Hegerl U, Kohls E, Bot M, Roca M. Soft Drinks and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety in Overweight Subjects: A Longitudinal Analysis of an European Cohort. Nutrients. 2023;15:3865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Skogen JC, Knudsen AK, Myrtveit SM, Sivertsen B. Abstention, alcohol consumption, and common somatic symptoms: the Hordaland Health Study (HUSK). Int J Behav Med. 2015;22:24-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Fuchs KH, DeMeester TR, Otte F, Broderick RC, Breithaupt W, Varga G, Musial F. Severity of GERD and disease progression. Dis Esophagus. 2021;34:doab006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mehta RS, Nguyen LH, Ma W, Staller K, Song M, Chan AT. Association of Diet and Lifestyle With the Risk of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Symptoms in US Women. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:552-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Bert F, Pompili E, Lo Moro G, Corradi A, Sagrawa Caro A, Gualano MR, Siliquini R. Prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: An Italian cross-sectional survey focusing on knowledge and attitudes towards lifestyle and nutrition. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e13758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Yamamichi N, Mochizuki S, Asada-Hirayama I, Mikami-Matsuda R, Shimamoto T, Konno-Shimizu M, Takahashi Y, Takeuchi C, Niimi K, Ono S, Kodashima S, Minatsuki C, Fujishiro M, Mitsushima T, Koike K. Lifestyle factors affecting gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a cross-sectional study of healthy 19864 adults using FSSG scores. BMC Med. 2012;10:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Lifestyle related risk factors in the aetiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Gut. 2004;53:1730-1735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Yan L, Wang Y, Hu H, Yang D, Wang W, Luo Z, Wang Y, Yang F, So KF, Zhang L. Physical exercise mediates cortical synaptic protein lactylation to improve stress resilience. Cell Metab. 2024;36:2104-2117.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Pearce M, Garcia L, Abbas A, Strain T, Schuch FB, Golubic R, Kelly P, Khan S, Utukuri M, Laird Y, Mok A, Smith A, Tainio M, Brage S, Woodcock J. Association Between Physical Activity and Risk of Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79:550-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 746] [Article Influence: 186.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Losa M, Manz SM, Schindler V, Savarino E, Pohl D. Increased visceral sensitivity, elevated anxiety, and depression levels in patients with functional esophageal disorders and non-erosive reflux disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33:e14177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Li Q, Duan H, Wang Q, Dong P, Zhou X, Sun K, Tang F, Wang X, Lin L, Long Y, Sun X, Tao L. Analyzing the correlation between gastroesophageal reflux disease and anxiety and depression based on ordered logistic regression. Sci Rep. 2024;14:6594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Choi JM, Yang JI, Kang SJ, Han YM, Lee J, Lee C, Chung SJ, Yoon DH, Park B, Kim YS. Association Between Anxiety and Depression and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Results From a Large Cross-sectional Study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24:593-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Zamani M, Alizadeh-Tabari S, Chan WW, Talley NJ. Association Between Anxiety/Depression and Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:2133-2143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Yang XJ, Jiang HM, Hou XH, Song J. Anxiety and depression in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and their effect on quality of life. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4302-4309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 53. | Alwhaibi M. Anxiety and Depression and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Population-Based Study. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11:2637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Guadagnoli L, Abber S, Geeraerts A, Geysen H, Pauwels A, Tack J, Van Oudenhove L, Vanuytsel T. Physiological and Psychological Factors Contribute to Real-Time Esophageal Symptom Reporting in Patients With Refractory Reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025;120:344-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Ribolsi M, Marchetti L, Blasi V, Cicala M. Anxiety correlates with excessive air swallowing and PPI refractoriness in patients with concomitant symptoms of GERD and functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35:e14550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Matsuhashi N, Kudo M, Yoshida N, Murakami K, Kato M, Sanuki T, Oshio A, Joh T, Higuchi K, Haruma K, Nakada K. Factors affecting response to proton pump inhibitor therapy in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a multicenter prospective observational study. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1173-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Guadagnoli L, Geeraerts A, Geysen H, Pauwels A, Vanuytsel T, Tack J, Van Oudenhove L. Psychological Processes, Not Physiological Parameters, Are Most Important Contributors to Symptom Severity in Patients With Refractory Heartburn/Regurgitation Symptoms. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:848-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Roman S, Keefer L, Imam H, Korrapati P, Mogni B, Eident K, Friesen L, Kahrilas PJ, Martinovich Z, Pandolfino JE. Majority of symptoms in esophageal reflux PPI non-responders are not related to reflux. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:1667-1674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Carlson DA, Gyawali CP, Roman S, Vela M, Taft TH, Crowell MD, Ravi K, Triggs JR, Quader F, Prescott J, Lin FTJ, Mion F, Biasutto D, Keefer L, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Esophageal Hypervigilance and Visceral Anxiety Are Contributors to Symptom Severity Among Patients Evaluated With High-Resolution Esophageal Manometry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:367-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Sharma A, Van Oudenhove L, Paine P, Gregory L, Aziz Q. Anxiety increases acid-induced esophageal hyperalgesia. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:802-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Huang KY, Hu JY, Lv M, Wang FY, Ma XX, Tang XD, Lv L. Cerebral cortex changes in FD, IBS, and GERD: A Mendelian randomization study. J Affect Disord. 2025;369:1153-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/