Published online Dec 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.112926

Revised: September 3, 2025

Accepted: October 22, 2025

Published online: December 7, 2025

Processing time: 116 Days and 1.2 Hours

Perianal abscesses (PA) and pediatric fistula-in-ano (PFIA) are stages of the same perianal infectious disease, with PFIA often developing from PA. In children, PFIA predominantly affects male infants under one year, mostly involving low-level fistulas. The pathogenesis remains unclear, though infection and inflammation play central roles. Novel inflammatory markers, such as systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), neutro

To analyze changes in CBC and inflammatory markers in male infants and toddlers with PFIA.

Among 974 male infants and toddlers under six years of age, the case and control groups comprised 681 patients with PFIA and 293 healthy individuals, respec

PFIA was significantly associated with CBC-derived inflammatory markers. Compared with healthy controls, patients with PFIA demonstrated higher lymphocyte and lower MLR and SIRI levels, which remained robust after adjusting for patient age. Lymphocyte count, MLR, and SIRI had high predictive values. Additionally, lymphocyte count, MLR, and SIRI showed high clinical utility across a wide range of threshold probabilities, thus enhancing early detection and prognostic prediction. Finally, the number of fistula tracts in patients was significantly correlated with lymphocyte, MLR, and SIRI levels.

Lymphocyte count may be an inflammatory biomarker in the evaluation of PFIA among male infants and toddlers. Closer clinical observation and timely preventive or diagnostic measures will be beneficial.

Core Tip: This retrospective case-control study analyzed 974 male infants and toddlers, including 681 with pediatric fistula-in-ano (PFIA) and 293 healthy controls, to assess the relationship between complete blood count-derived inflammatory markers and PFIA. Patients showed higher lymphocyte counts but lower monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) and systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) levels, which remained significant after age adjustment. Lymphocyte count, MLR, and SIRI demonstrated strong predictive value and clinical utility for PFIA detection and prognosis. The number of fistula tracts correlated with these markers. Lymphocyte count may serve as a useful biomarker, supporting early diagnosis and targeted prevention in pediatric PFIA.

- Citation: Ma HF, Chen YH, Wang Y, Zhang XC, Li JN, Wang YM, Zhou ZY. Complete blood counts and their derived inflammatory markers with anal fistulas in male children: A retrospective case-control study. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(45): 112926

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i45/112926.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.112926

Perianal abscess (PA) and pediatric fistula-in-ano (PFIA) represent different stages of the same perianal infection, with PA reflecting the acute phase and PFIA the chronic phase. PA usually presents as a painful perianal mass with local inflammation, and if not properly treated, can progress to PFIA or other fistulous complications that significantly impact quality of life[1].

PFIA differs from adult PFIA[2]. Although data remain limited, evidence suggests that pediatric PFIA mainly involves low-level fistulas, occurs predominantly in boys[3], and develops mostly in infants under one year[4]. The incidence of PAs is about 0.5%-4.3%[5], with 20%-85% progressing to PFIA[6]. Reported risk factors include diarrhea, high maternal parity, and frequent perianal wiping[7]. Due to its prevalence, morbidity, and economic burden, PFIA represents an important public health concern.

The pathogenesis of PFIA remains unclear despite several proposed etiologies[8]. The classic “cryptoglandular hypothesis” links PFIA to infection, with crypt abnormalities predisposing children to cryptitis and anal gland infection as the presumed source of most cases[9]. In infants, inadequate perianal care may also result in infections from perianal skin lesions[10], anal fissures[11], or inflammatory bowel disease[12]. Inflammation, as a potentially modifiable factor, is central to prevention and treatment strategies.

Recently, novel inflammatory markers, including the systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), have emerged as significant indicators of the onset and progression of inflammatory and infectious diseases[13-15]. Given the intricate network linking immunity, inflammation, and disease, composite markers offer a more accurate and meaningful approach to capture overall inflammatory states and reflect diverse immuno-inflammatory profiles.

However, to date, no studies have explored the relationship between complete blood count (CBC) and its derived inflammatory biomarkers with PFIA. Therefore, this single-center, retrospective, case-control study aimed to assess the association between CBC, its derived markers, and PFIA using representative clinical data to provide an epidemiological basis for the diagnosis and prognosis of PFIA. These findings may deepen our understanding of PFIA pathogenesis and provide insights into potential intervention strategies.

This study included 974 male children under 6 years of age who visited the Department of Colorectal Surgery at our institution between January 2018 and March 2024. Of these, 681 children diagnosed with PFIA and 293 healthy male children were assigned to the case and control groups, respectively. The control group was composed of healthy children screened through the physical examination center of the Unified Center, and children with unrelated mild illnesses or subclinical infections that might affect complete blood cell counts were excluded.

All participants met the following inclusion criteria: (1) Diagnosis of PFIA based on the 2016 Guidelines for the Management of Anal Abscess and Fistula developed by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and Parks Classification System; (2) Male children < 6 years of age; (3) Absence of cellulitis, systemic infection signs, or underlying immunosuppression; (4) No severe cardiovascular, hepatic, renal diseases, malignancies, or hematological disorders; and (5) PFIA not caused by specific conditions, such as tuberculosis, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis. The exclusion criteria for the healthy control group were as follows: (1) Participants with no severe anorectal disease other than mild hemorrhoids or perianal dermatological conditions; (2) Presence of specific PFIA due to tuberculosis, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis; (3) Comorbidities such as rectal polyps, rectal cancer, or severe mixed hemorrhoids; and (4) History of allergies or mental disorders.

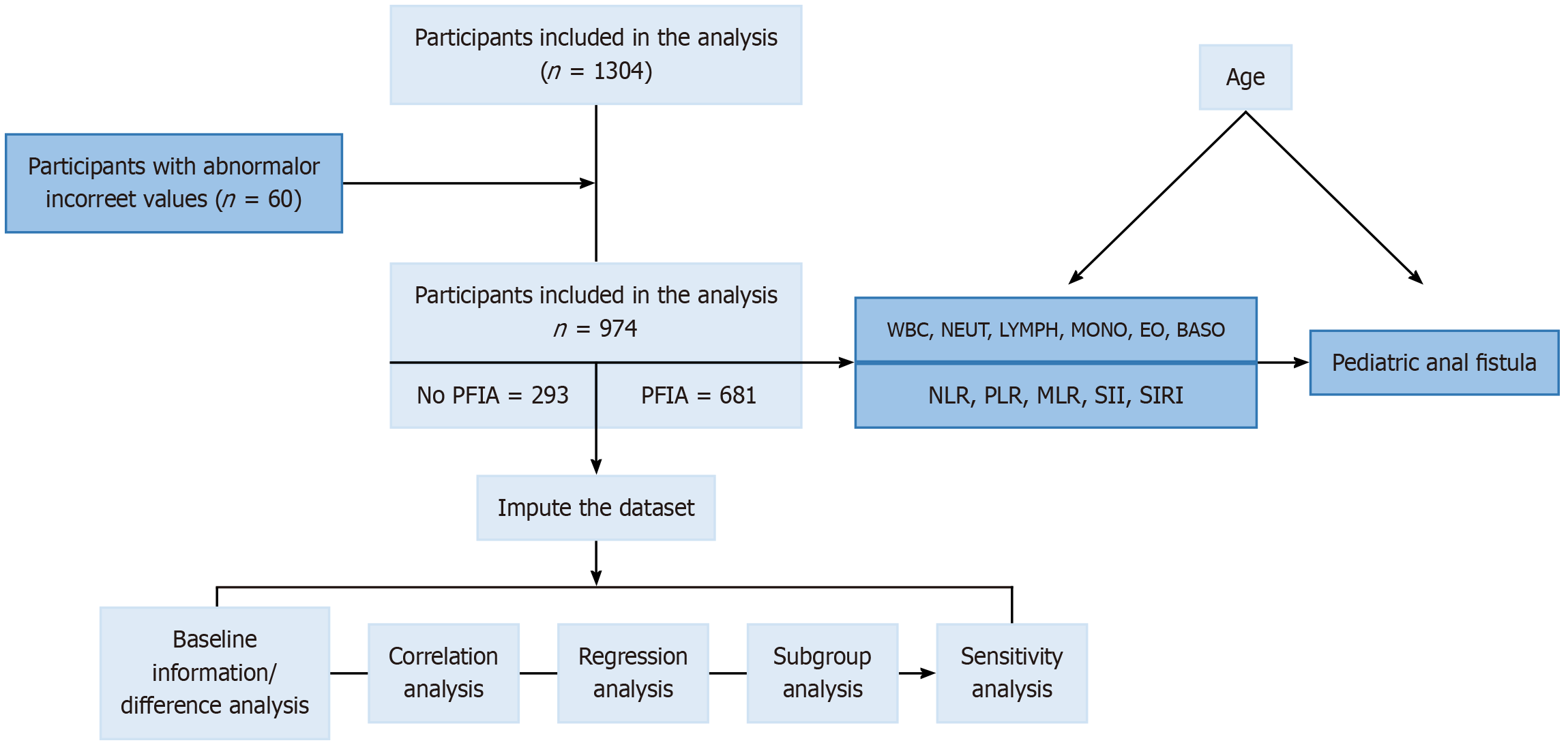

The sample size was predetermined as described in the Supplementary material. The primary study variable was the presence or absence of PFIA, while the secondary variable was the number of fistulas. The study flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

This study is a retrospective analysis, using data derived from previous case records that were anonymized prior to data collection. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of our institution (approval No. 2024-KY-387) and was conducted in strict accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonization-Good Clinical Practice, and relevant laws and regulations. Given that the study is retrospective and poses minimal risk to participants (including minors under the age of 16), the ethics committee waived the requirement for informed consent according to relevant regulations. Therefore, all data used in this study were utilized under a waiver of informed consent, and no separate informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of minors.

Blood samples were collected on the day of admission from hospitalized patients and the day of consultation from outpatients and healthy participants. CBC and related parameters were measured using an automated hematology analyzer (XN9000, Sysmex Corporation, Japan).

The CBC parameters included white blood cell (WBC), neutrophil, monocyte, eosinophil, and basophil counts. Derived inflammatory biomarkers were calculated using the following formulas: NLR = neutrophil/Lymphocyte counts; PLR = platelet/Lymphocyte counts; MLR = monocyte/Lymphocyte counts; SII = platelet count × NLR; SIRI = neutrophil count × MLR.

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD, and categorical variables as numbers and percentages. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the normality of the data distributions. Non-normally distributed data are represented as medians and interquartile range (IQR) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. The relationships between PFIA and various parameters were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation and Mantel’s test. Logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between CBC parameters and inflammatory biomarkers derived from PFIA by estimating the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Both crude and adjusted models were used, with age as a covariate in the adjusted model. Bootstrap resampling (10000 iterations) was performed to validate the sensitivity. A subgroup analysis stratified by age was conducted to assess the robustness of the findings. To evaluate the clinical utility of CBC parameters and derived biomarkers, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and decision curve analysis (DCA) were performed to assess their diagnostic and predictive values for PFIA.

The available sample size in this retrospective study was considered sufficient based on statistical power considerations. Assuming a two-sided significance level of 0.05, 80% power, and an effect size corresponding to an OR of 1.5-2.0 for key indicators (e.g., lymphocyte and WBC counts), at least 250-300 subjects per group would be required according to prior pediatric studies. Our study included 681 PFIA cases and 293 controls, which exceeded this threshold and was therefore adequately powered to detect clinically meaningful associations. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software, version 4.3.3 (https://cran.r-project.org). Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed P < 0.05.

The median age of the 974 participants was 12 months (IQR: 9.0-31.0), and 11 (IQR: 8.0-12.0) and 16 (IQR: 12.0-48.0) months in the case and control groups, respectively.

The CBC parameters differed significantly between the case and control groups, with higher WBC [9.8 (7.8-12.1) × 109/L vs 6.0 (4.8-7.0) × 109/L, P < 0.001] and lymphocyte [6.2 (4.7-8.1) × 109/L vs 2.1 (1.5-2.6) × 109/L, P < 0.001] and lower neutrophil [2.5 (1.9-3.3) × 109/L vs 3.0 (2.2-4.1) × 109/L, P < 0.001] counts in the case group compared with the control group. Additionally, the derived immune-inflammatory indices, including NLR, PLR, MLR, SII, and SIRI, were significantly lower in the case group than in the control group (Table 1). We also demonstrated the relationship between CBC parameters and the number of fistulas in the case and control groups (Supplementary Table 1).

| Variable | Total (n = 974) | Control (n = 293) | Case (n = 681) | P value | Z value |

| Age (months), median IQR | 12.0 (9.0-31.0) | 16.0 (12.0-48.0) | 11.0 (8.0-12.0) | < 0.001 | -19.484 |

| WBC (× 109/L), median IQR | 8.3 (6.4-11.0) | 6.0 (4.8-7.0) | 9.8 (7.8-12.1) | < 0.001 | 5.711 |

| NEUT (× 109/L), median IQR | 2.7 (1.9-3.6) | 3.0 (2.2-4.1) | 2.5 (1.9-3.3) | < 0.001 | -23.839 |

| LYMPH (× 109/L), median IQR | 4.9 (2.7-7.2) | 2.1 (1.5-2.6) | 6.2 (4.7-8.1) | < 0.001 | -2.658 |

| MONO (× 109/L), median IQR | 0.5 (0.4-0.6) | 0.5 (0.4-0.6) | 0.5 (0.4-0.6) | 0.008 | -17.460 |

| EO (× 109/L), median IQR | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) | 0.1 (0.0-0.1) | 0.2 (0.2-0.4) | < 0.001 | -16.209 |

| BASO (× 109/L), median IQR | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | < 0.001 | 21.915 |

| NLR, median IQR | 0.5 (0.3-1.1) | 1.5 (1.0-2.2) | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | < 0.001 | 16.291 |

| PLR, median IQR | 66.5 (46.7-90.8) | 95.5 (74.9-122.0) | 55.9 (40.5-75.1) | < 0.001 | 22.783 |

| MLR, median IQR | 0.1 (0.1-0.2) | 0.2 (0.2-0.3) | 0.1 (0.1-0.1) | < 0.001 | 15.205 |

| SII, median IQR | 169.8 (104.9-267.0) | 279.4 (192.2-436.4) | 137.4 (88.7-198.6) | < 0.001 | 19.255 |

| SIRI, median IQR | 0.3 (0.2-0.6) | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) | < 0.001 | 18.273 |

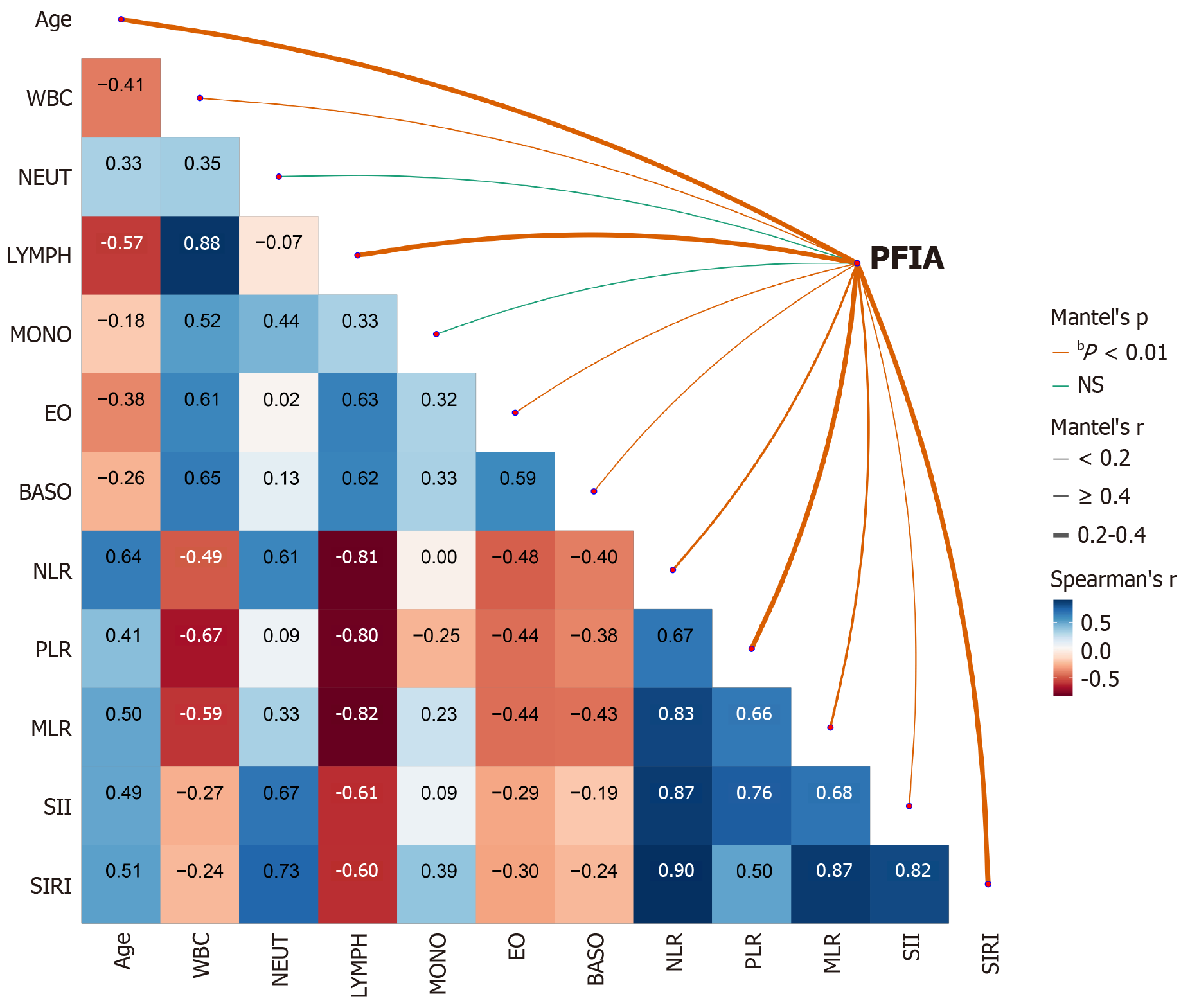

Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between CBC parameters, derived inflammatory biomarkers, the presence of PFIA, and fistula count. Mantel’s test was used to further explore these associations. The results indicated significant correlations between PFIA and age (r = 0.299); WBC (r = 0.185); lymphocyte (r = 0.371), eosinophil (r = 0.052), and basophil (r = 0.075) counts; SIRI (r = 0.337); SII (r = 0.167); NLR (r = 0.459); PLR (r = 0.248); and MLR (r = 0.445) (P < 0.05). In contrast, neutrocyte and monocyte counts were not significantly associated with PFIA (P > 0.05) (Figure 2). Furthermore, significant correlations were observed between fistula count and age; WBC, neutrophil, lymphocyte, eosinophil, and basophil count; NLR; PLR; MLR; and SIRI (P < 0.05), with neutrocyte count, NLR, and PLR showing the strongest associations. Conversely, monocyte count and SII were not significantly correlated with fistula count (P > 0.05) (Supplementary Figure 1). Overall, age; WBC, lymphocyte, eosinophil, and basophil counts; and SIRI were significantly associated with both PFIA and fistula count, whereas monocyte count was not.

Logistic regression analysis adjusted for age demonstrated that WBC (OR = 2.18, 95%CI: 1.94-2.47), lymphocyte (OR = 17.78, 95%CI: 11.24-30.34), eosinophil (OR = 1.11, 95%CI: 1.09-1.13), and basophil (OR = 2.52, 95%CI: 2.17-2.94) counts were significantly associated with an increased risk of PFIA. Conversely, the NLR (OR = 0.05, 95%CI: 0.03-0.09), PLR (OR = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.97-0.98), MLR (OR = 0.80, 95%CI: 0.77-0.82), SII (OR = 0.78, 95%CI: 0.70-0.86), and SIRI (OR = 0.05, 95%CI: 0.03-0.08) were associated with a lower risk of PFIA. The monocyte and neutrophil scores were not significantly associated with the risk of PFIA (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

| Variable | Crude OR (95%CI) | Crude P value | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted P value |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 2.31 (2.06-2.60) | < 0.001 | 2.18 (1.94-2.47) | < 0.001 |

| NEUT (× 109/L) | 0.86 (0.78-0.93) | 0.001 | 1.03 (0.93-1.15) | 0.577 |

| LYMPH (× 109/L) | 15.90 (10.32-26.41) | < 0.001 | 17.78 (11.24-30.34) | < 0.001 |

| MONO (× 109/L) | 3.34 (1.60-7.32) | 0.002 | 1.04 (0.60-2.14) | 0.899 |

| EO (× 109/L) | 1.13 (1.11-1.15) | < 0.001 | 1.11 (1.09-1.13) | < 0.001 |

| BASO (× 109/L) | 2.46 (2.16-2.83) | < 0.001 | 2.52 (2.17-2.94) | < 0.001 |

| NLR | 0.04 (0.03-0.06) | < 0.001 | 0.05 (0.03-0.09) | < 0.001 |

| PLR | 0.96 (0.96-0.97) | < 0.001 | 0.97 (0.97-0.98) | < 0.001 |

| MLR | 0.77 (0.76-0.80) | < 0.001 | 0.80 (0.77-0.82) | < 0.001 |

| SII | 0.62 (0.57-0.68) | < 0.001 | 0.78 (0.70-0.86) | < 0.001 |

| SIRI | 0.03 (0.01-0.04) | < 0.001 | 0.05 (0.03-0.08) | < 0.001 |

Linear regression analysis also revealed significant correlations between CBC parameters and fistula count. Elevated CBC levels were associated with an increased risk of a higher fistula count, whereas increased levels of derived inflammatory biomarkers were associated with a lower risk of additional fistulas (Supplementary Table 2).

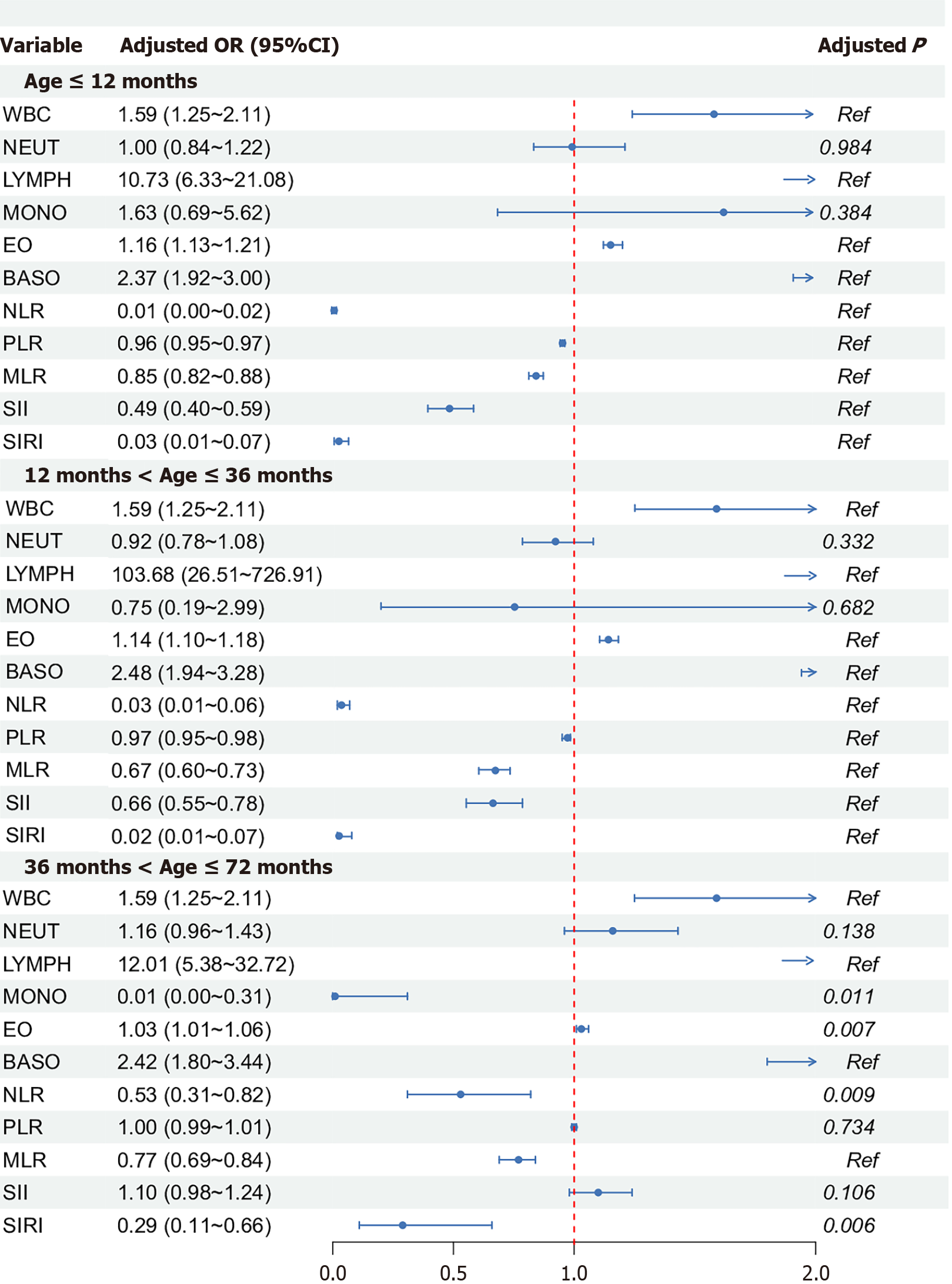

We conducted a subgroup analysis based on the median age to examine the relationship between CBC parameters, derived inflammatory biomarkers, and the risk of PFIA occurrence at different age levels. The results indicated a stronger potential and significance for the relationship between lymphocyte count and disease risk among children aged 12 and 36 months than the other two age groups. In the age-based subgroup analysis, WBC, lymphocyte, eosinophil, and basophil counts; NLR; MLR; and SIRI were significantly associated with PFIA risk in all age groups (P < 0.05), while neutrocyte count was not significantly associated with PFIA risk in any group (P > 0.05). In children < 36 months of age, monocyte count was not significantly associated with PFIA risk, while in children > 36 months, PLR and SII were not significantly correlated with PFIA risk (Figure 3). In the analysis of the secondary outcome the number of fistulas and CBC parameters and derived inflammatory biomarkers, age-stratified analysis showed that the association between lymphocyte count and PFIA risk was most pronounced in children aged 12-36 months. WBC, lymphocyte, eosinophil, and basophil counts, as well as NLR, MLR, and SIRI, were significantly associated with PFIA risk across all age groups (P < 0.05), whereas neutrophil count showed no significant association in any age group. Monocyte count was not sig

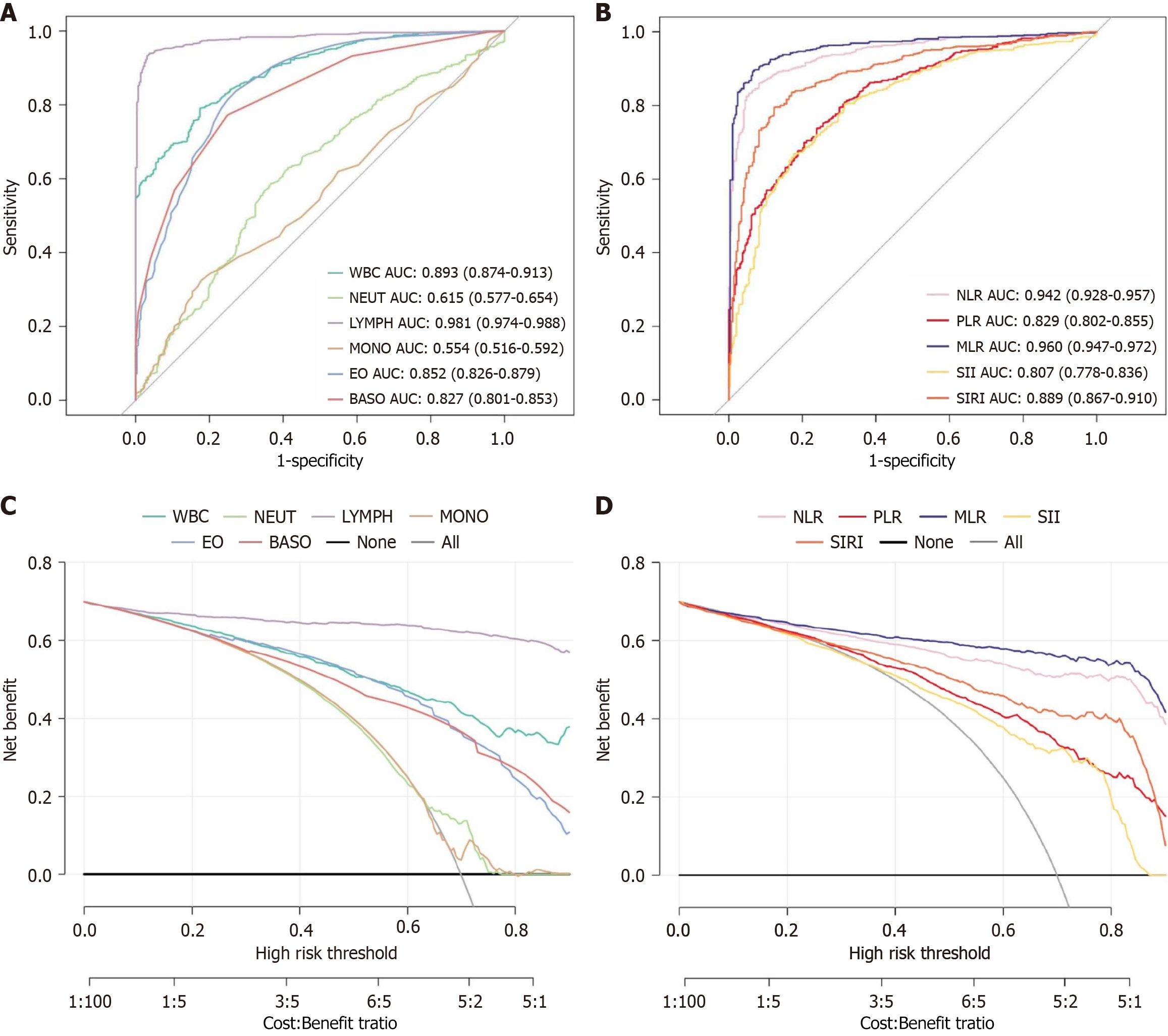

In the analysis of PFIA prediction, ROC curve analysis and area under the ROC curve (AUC) calculations were performed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of CBC and derived biomarkers. The ROC curve analysis revealed the highest predictive value for lymphocyte count, with superior sensitivity and specificity. The predictive values of the other biomarkers decreased in the following order: MLR, NLR, WBC count, SIRI, eosinophil count, basophil count, PLR, SII, neutrophil count, and monocyte count, indicating a gradual reduction in diagnostic effectiveness (Figure 4).

Specifically, lymphocyte count showed the highest specificity, with an AUC of 0.981 and specificity of 0.962, demonstrating exceptional accuracy in distinguishing patients with PFIA from those without PFIA. The next highest values were MLR and NLR, with AUCs of 0.960 and 0.942 and specificities of 0.932 and 0.918, respectively, both showing a high diagnostic value.

WBC count, SIRI, eosinophil count, and basophil count had AUC values > 0.800, with specificities of 0.826, 0.877, 0.727, and 0.751, respectively, indicating good diagnostic performance. Although PLR, SII, and neutrophil count had statistically significant AUC values (P < 0.05), their specificities were relatively low (0.761, 0.823, and 0.635, respectively), indicating a lower diagnostic accuracy. Monocyte count showed the lowest AUC (0.554) with a specificity of 0.823, suggesting its limited clinical value in predicting PFIA.

Across a broad range of threshold probabilities, the lymphocyte count demonstrated the highest clinical value, indicating that it provided the most significant benefit for clinical decision-making at various possible decision thresholds. In comparison, the clinical values of MLR, NLR, WBC count, SIRI, eosinophil count, basophil count, PLR, and SII decreased sequentially, reflecting a reduced contribution to clinical decision support. Notably, neutrophil and monocyte counts had almost no clinical value in the DCA, indicating their minimal contributions to clinical decision-making.

This retrospective study aimed to explore the potential clinical value of changes in CBC parameters and their derived inflammatory biomarkers in male infants under 6 years of age with PFIA. The findings indicated that CBC indicators, including WBC, lymphocyte, and neutrophil counts, were associated with PFIA occurrence, with lymphocyte count showing the highest discriminatory performance (AUC = 0.981). Binary logistic regression analysis further supported the association between these markers and the risk of disease onset, particularly suggesting a positive relationship between WBC and lymphocyte counts and PFIA. In addition, ROC curves and DCA results suggested that lymphocyte count may offer relatively higher clinical utility than other indicators in decision-making.

PFIA is considered a chronic inflammatory condition, often thought to result from anal gland infections triggered by factors such as anal fissures, local skin infections, diarrhea, inadequate perianal hygiene, or frequent wiping[7-12]. Anal gland infections can lead to cryptitis, and some studies have proposed that susceptibility may be influenced by the developmental activity of anal glands, which could be affected by androgen levels[16-18]. Given that anal glands are actively developing in young male children, this condition appears more frequently in this population[5]. PFIA involves various inflammatory cells, including WBCs, basophils, eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes. The distribution and function of these cells may vary depending on factors such as sex, age, disease severity, and underlying immune conditions. However, limited research has directly examined the role of specific inflammatory cells in PFIA, and most studies have provided only indirect evidence of these associations.

In recent years, CBC parameters and their derived inflammatory ratios have been examined for their prognostic relevance in several diseases, including malignancies[19-21] cardiovascular disorders[22,23], and respiratory failure[24,25], yielding important insights. Inspired by these findings, we investigated whether these routinely available markers could aid in the early identification of PFIA. While auxiliary diagnostic methods for PFIA, such as manual examination, rectal ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging can be informative, they are not always feasible in very young children due to their invasive nature and technical complexity. Therefore, blood-based indicators may serve as a non

The current study contributes to the field by examining associations between PFIA and CBC-derived biomarkers in a relatively large and representative pediatric sample. Comparisons between 681 PFIA cases and 293 healthy controls identified several potentially informative indicators. Elevated lymphocyte, WBC, eosinophil, and basophil counts, along with reduced levels of MLR, NLR, SIRI, PLR, and SII, were significantly associated with PFIA. Among these, lymphocyte count, WBC, MLR, NLR, and SIRI demonstrated relatively high AUC values, suggesting their potential diagnostic utility. DCA results further indicated that lymphocyte count may offer greater net benefit in clinical decision-making compared with other markers. Although ROC and DCA analyses in our study primarily provide theoretical evidence of diagnostic and clinical utility, similar analytic tools have been adopted in pediatric research to support early clinical insights prior to prospective validation. For example, in pediatric acute appendicitis, NLR has shown moderate but reliable diagnostic accuracy in both retrospective studies and a meta-analysis Eun et al[26] reported pooled sensitivity of 0.82 (95%CI: 0.79-0.85), specificity of 0.76 (95%CI: 0.69-0.81), and AUC of 0.86. Goodman et al[27] similarly found that NLR > 3.5 detected 88% of appendicitis cases, outperforming total WBC count. These precedents illustrate how ROC-based tools may offer meaningful early clinical insight even without prospective outcome data. Applied to our context, the ROC and DCA findings suggest potential utility of CBC-derived markers in PFIA risk stratification. Although our DCA findings primarily provide theoretical support for potential clinical utility, the use of DCA as an early evaluative tool is now well-established in pediatric and surgical research. For example, one study applied DCA to assess the net benefit of prognostic scoring systems for predicting mortality in children with severe sepsis, demonstrating tangible clinical value even in the absence of workflow implementation[28]. Similarly, another study evaluated the clinical utility of post-febrile urinary tract infection ultrasonography using DCA, showing its usefulness in guiding follow-up decisions without requiring actual diagnostic integration[29]. By analogy, our DCA results highlight the promise of CBC-derived inflammatory markers in PFIA risk stratification. Nevertheless, prospective validation, workflow integration, and cost-effectiveness analysis are needed to confirm their real-world impact. Nevertheless, prospective interventional validation remains necessary to confirm whether their use translates into improved patient outcomes.

Subgroup analysis revealed a consistent positive association between lymphocyte count and PFIA across different age groups, underscoring the potential importance of monitoring this parameter in younger populations. Increased lymphocyte levels may reflect immune activation in response to infection and could be involved in the disease process. Bostick and Zhou[30] demonstrated that innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) play critical roles in mucosal immunity and inflammation in the gut, which may have relevance for PFIA given the anatomical and functional similarities of the rectum to the lower gastrointestinal tract. ILCs contribute to pathogen defense, immune regulation, and tissue repair, especially during chronic inflammatory responses[31-33]. Elevated lymphocyte levels might be consistent with ILC-mediated immune activity, including interferon-gamma production by ILC1 cells, as previously described by Klose et al[31].

Moreover, nutritional and metabolic influences on ILC function should not be overlooked. For instance, vitamins A and D have been reported to regulate ILC responses[34,35]; vitamin A derivatives, in particular, enhance ILC3-mediated interleukin-22 production, which protects intestinal epithelial integrity[35,36]. These findings suggest that prenatal and early postnatal nutritional status might influence PFIA susceptibility through immunological mechanisms involving ILCs.

In summary, our findings suggest that CBC parameters and derived inflammatory markers especially lymphocyte count, WBC, MLR, NLR, and SIRI may have potential value in PFIA assessment. Although these markers are not a substitute for established diagnostic tools, they could serve as supportive indicators, particularly in settings where invasive methods are not feasible. Incorporating these noninvasive biomarkers may facilitate earlier recognition and appropriate management of suspected PFIA cases. Nonetheless, further prospective studies and mechanistic investigations are needed to confirm these observations and determine their broader applicability in clinical practice. Furthermore, in male children presenting with perianal discomfort, elevated WBC, eosinophil, or basophil counts, or decreased MLR, NLR, SIRI, PLR, and SII values, may warrant closer clinical attention, as they could reflect a potential risk to perianal health that merits further evaluation. The relatively high AUC values observed in this study may be partly attributable to the homogeneous pediatric population and strict inclusion criteria, which reduced variability and enhanced discrimination. However, the lack of external validation raises concerns about potential overfitting, and future multicenter studies with independent validation are warranted to confirm these findings.

Our study focused exclusively on male infants, as epidemiological evidence indicates that PFIA occurs predominantly in this population. In addition to these trends, this male bias is robustly supported by recent evidence. A 2023 systematic review encompassing 18 studies with 1770 infants reported that 84.7% of PA and anal fistula cases occurred in male patients[37]. Moreover, recent comprehensive reviews on the pathogenesis of perianal fistulas highlight male sex as a significant risk factor, suggesting inherent biological susceptibility[38]. Taken together, these epidemiological and mechanistic insights justify the focus on male children in our study. Nevertheless, future research is warranted to include sufficient female cases to explore potential sex-dependent differences in PFIA pathogenesis and presentation.

This study has several limitations. It was a retrospective single-center analysis with a relatively small sample, which may introduce selection bias and restrict generalizability. CBC-derived inflammatory markers are not disease-specific and may overlap with other pediatric inflammatory conditions, despite strict inclusion criteria. Multiple comparisons may increase the risk of type I error; although multivariable modeling adjustment were applied to mitigate confounding and bias, false-positive findings cannot be fully excluded. Accordingly, we emphasized the most consistent and biologically plausible markers, such as lymphocyte count, while regarding other associations as exploratory. Moreover, our study focused on statistical associations without mechanistic evidence, and future molecular and immunological studies are needed to clarify causal pathways. Finally, the absence of external or prospective validation may overestimate predictive performance, highlighting the need for large-scale, multicenter cohorts to confirm and generalize these findings.

Lymphocytes appear to be associated with PFIA, potentially reflecting their involvement in immune responses and chronic inflammatory activity. However, causal mechanisms remain uncertain, and further studies are needed to clarify the roles of specific lymphocyte subpopulations and to explore possible interactions with the gut microbiome and metabolic factors. Such investigations may provide additional insights into PFIA pathogenesis and inform prevention or management approaches. In pediatric PFIA, lymphocyte count may represent a useful, though nonspecific, indicator of inflammation. Moreover, the observed patterns of elevated WBCs, eosinophils, and basophils, together with reduced MLR, NLR, SIRI, PLR, and SII values, could warrant closer clinical attention in young males presenting with perianal discomfort, as they may signal underlying perianal inflammatory activity.

| 1. | Ji L, Zhang Y, Xu L, Wei J, Weng L, Jiang J. Advances in the Treatment of Anal Fistula: A Mini-Review of Recent Five-Year Clinical Studies. Front Surg. 2020;7:586891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kang C, Liu G, Zhang R, Chenk J, Yan C, Guo C. Intermediate-Term Evaluation of Initial Non-Surgical Management of Pediatric Perianal Abscess and Fistula-In-Ano. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2022;23:465-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ding C, Chen Y, Yan J, Wang K, Tan SS. Risk factors for therapy failure after incision and drainage alone for perianal abscesses in children. Front Pediatr. 2024;12:1342892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sun Y, Hao S, Zhang X, Liang H, Yao Y, Lu J, Wang C. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Comparing Drainage Alone versus Drainage with Primary Fistula Treatment for the Perianal Abscess in Children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2024;34:204-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gong Z, Han M, Wu Y, Huang X, Xu WJ, Lv Z. Treatment of First-Time Perianal Abscess in Childhood, Balance Recurrence and Fistula Formation Rate with Medical Intervention. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2018;28:373-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Park J. Management of perianal abscess and fistula-in-ano in infants and children. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2020;63:261-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sun Y, Liang H, Hao S, Yin L, Pan Y, Wang C, Lu J. A case-control study of the risk factors for fistula-in-ano in infants and toddlers. BMC Pediatr. 2024;24:362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Włodarczyk M, Włodarczyk J, Sobolewska-Włodarczyk A, Trzciński R, Dziki Ł, Fichna J. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of cryptoglandular perianal fistula. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:300060520986669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lin CA, Chou CM, Huang SY, Chen HC. The Optimal Primary Treatment for Pediatric Perianal Abscess and Anal Fistula: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2023;58:1274-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ding W, Sun YR, Wu ZJ. Treatment of Perianal Abscess and Fistula in Infants and Young Children: From Basic Etiology to Clinical Features. Am Surg. 2021;87:927-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gosemann JH, Lacher M. Perianal Abscesses and Fistulas in Infants and Children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2020;30:386-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mortreux P, Leroyer A, Dupont C, Ley D, Bertrand V, Spyckerelle C, Guillon N, Wils P, Gower-Rousseau C, Savoye G, Fumery M, Turck D, Siproudhis L, Sarter H. Natural History of Anal Ulcerations in Pediatric-Onset Crohn's Disease: Long-Term Follow-Up of a Population-Based Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:1671-1678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang RH, Wen WX, Jiang ZP, Du ZP, Ma ZH, Lu AL, Li HP, Yuan F, Wu SB, Guo JW, Cai YF, Huang Y, Wang LX, Lu HJ. The clinical value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the occurrence and severity of pneumonia in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1115031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Biyik M, Biyik Z, Asil M, Keskin M. Systemic Inflammation Response Index and Systemic Immune Inflammation Index Are Associated with Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Acute Pancreatitis? J Invest Surg. 2022;35:1613-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu W, Wang J, Wang M, Ding X, Wang M, Liu M. Association between immune-inflammatory indexes and lower urinary tract symptoms: an analysis of cross-sectional data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2005-2008). BMJ Open. 2024;14:e080826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ye S, Huang Z, Zheng L, Shi Y, Zhi C, Liu N, Cheng Y. Restricted cubic spline model analysis of the association between anal fistula and anorectal abscess incidence and body mass index. Front Surg. 2023;10:1329557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Roskam M, de Meij T, Gemke R, Bakx R. Perianal Abscesses in Infants Are Not Associated With Crohn's Disease in a Surgical Cohort. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:773-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ezer SS, Oğuzkurt P, Ince E, Hiçsönmez A. Perianal abscess and fistula-in-ano in children: aetiology, management and outcome. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46:92-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen H, Wu X, Wen Z, Zhu Y, Liao L, Yang J. The Clinicopathological and Prognostic Value of NLR, PLR and MLR in Non-Muscular Invasive Bladder Cancer. Arch Esp Urol. 2022;75:467-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Valero C, Pardo L, Sansa A, Garcia Lorenzo J, López M, Quer M, León X. Prognostic capacity of Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2020;42:336-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang Q, Zhu D. The prognostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) in patients after radical operation for carcinoma of stomach in gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10:965-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhao S, Dong S, Qin Y, Wang Y, Zhang B, Liu A. Inflammation index SIRI is associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among patients with hypertension. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:1066219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tosu AR, Biter Hİ. Association of systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) with presence of isolated coronary artery ectasia. Arch Med Sci Atheroscler Dis. 2021;6:e152-e157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shen Q, Mu X, Bao Y, Xu F, Zhang D, Luo A, Liu L, Huang H, Xu Y. An S-like curve relationship between systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) and respiratory failure in GBS patients. Neurol Sci. 2023;44:3279-3285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Huang L, Weng B, Wang M, Weng J, Du X, Ju Y, Zhong X, Tong X, Li Y. The improved prediction value of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio to pneumonia severity scores for mortality in the older people with community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Geriatr. 2025;25:485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Eun S, Ho IG, Bae GE, Kim H, Koo CM, Kim MK, Yoon SH. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for the diagnosis of pediatric acute appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25:7097-7107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Goodman DA, Goodman CB, Monk JS. Use of the neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio in the diagnosis of appendicitis. Am Surg. 1995;61:257-259. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Zhou LB, Chen J, DU XC, Wu SY, Bai ZJ, Lyu HT. [Value of three scoring systems in evaluating the prognosis of children with severe sepsis]. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2019;21:898-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Harper L, Delforge X, Maurin S, Leroy V, Michel JL, Sauvat F, Ferdynus C. A novel approach to evaluating the benefit of post-urinary tract infection renal ultrasonography, using decision curve analysis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31:1631-1636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bostick JW, Zhou L. Innate lymphoid cells in intestinal immunity and inflammation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:237-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Klose CSN, Flach M, Möhle L, Rogell L, Hoyler T, Ebert K, Fabiunke C, Pfeifer D, Sexl V, Fonseca-Pereira D, Domingues RG, Veiga-Fernandes H, Arnold SJ, Busslinger M, Dunay IR, Tanriver Y, Diefenbach A. Differentiation of type 1 ILCs from a common progenitor to all helper-like innate lymphoid cell lineages. Cell. 2014;157:340-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 761] [Cited by in RCA: 897] [Article Influence: 74.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Klose CS, Kiss EA, Schwierzeck V, Ebert K, Hoyler T, d'Hargues Y, Göppert N, Croxford AL, Waisman A, Tanriver Y, Diefenbach A. A T-bet gradient controls the fate and function of CCR6-RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2013;494:261-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 508] [Cited by in RCA: 606] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TK, Bucks C, Kane CM, Fallon PG, Pannell R, Jolin HE, McKenzie AN. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1765] [Cited by in RCA: 1734] [Article Influence: 108.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Spencer SP, Wilhelm C, Yang Q, Hall JA, Bouladoux N, Boyd A, Nutman TB, Urban JF Jr, Wang J, Ramalingam TR, Bhandoola A, Wynn TA, Belkaid Y. Adaptation of innate lymphoid cells to a micronutrient deficiency promotes type 2 barrier immunity. Science. 2014;343:432-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (15)] |

| 35. | van de Pavert SA, Ferreira M, Domingues RG, Ribeiro H, Molenaar R, Moreira-Santos L, Almeida FF, Ibiza S, Barbosa I, Goverse G, Labão-Almeida C, Godinho-Silva C, Konijn T, Schooneman D, O'Toole T, Mizee MR, Habani Y, Haak E, Santori FR, Littman DR, Schulte-Merker S, Dzierzak E, Simas JP, Mebius RE, Veiga-Fernandes H. Maternal retinoids control type 3 innate lymphoid cells and set the offspring immunity. Nature. 2014;508:123-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Keir M, Yi Y, Lu T, Ghilardi N. The role of IL-22 in intestinal health and disease. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20192195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 58.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Chen J, Xiong Y, Wang C, Xu L. Treatment of perianal abscess and anal fistula in infants: a systematic review. Front Surg. 2025;12:1572049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kawecki MP, Kruk AM, Drążyk M, Domagała Z, Woźniak S. Exploring Perianal Fistulas: Insights into Biochemical, Genetic, and Epigenetic Influences—A Comprehensive Review. Gastroenterol Insigh. 2025;16:10. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/