Published online Dec 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.112518

Revised: October 8, 2025

Accepted: November 4, 2025

Published online: December 7, 2025

Processing time: 120 Days and 18.9 Hours

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is an established therapeutic modality for early gastric cancer (EGC). Accurate assessment of the invasion depth is cri

To investigate the clinical significance of stereomicroscopy in determining the invasion depth of EGC.

This retrospective analysis included 967 patients with EGC who underwent ESD from 2014 to 2023. The mucosal and basal aspects of ESD specimens were stereomicroscopically examined. Lesions were categorized stereomicroscopically as mucosal (uniformly thick, transparent submucosal tissue) or submucosal defined by the presence of a “Basal White Sign”, a localized, opaque, whitish discoloration exceeding 5 mm in diameter. Patients with uncertain classification were excluded. The accuracy of stereomicroscopic depth diagnosis and clinicopathological fea

The overall diagnostic accuracy of stereomicroscopy for invasion depth was 74.0%. For non-ulcerated lesions, stereomicroscopy exhibited high diagnostic performance [accuracy = 93.5%, 95% confidence interval(CI): 91.1-95.4, sensitivity = 95.0%, specificity = 86.9%, positive predictive value = 96.9%, negative predictive value = 80.2%]. Conversely, performance significantly declined in ulcerated lesions (accuracy = 35.8%, 95%CI: 30.2-41.6, sensitivity = 19.1%, specificity = 95.2%, positive predictive value = 93.5%, negative predictive value = 24.8%). Tumor size of 21-30 mm (odds ratio = 1.6) and ulceration (odds ratio = 36.1) were independent risk factors for misdiagnosis. Submucosal lesions exhibited significantly larger basal vessel diameter than mucosal lesions (663.6 μm vs 505.5 μm, P < 0.001).

Stereomicroscopy is an effective diagnostic tool for determining the EGC invasion depth, particularly in non-ulcerated lesions. These findings could inform clinical practice and ESD treatment strategy optimization for EGC.

Core Tip: This study demonstrates that stereomicroscopy effectively assesses invasion depth in early gastric cancer, achieving 93.5% accuracy for non-ulcerated lesions, although the overall accuracy was 74.0% and only 35.8% for ulcerated lesions. Tumor size (21-30 mm) and ulceration are key misdiagnosis risk factors. These findings could guide stratified endoscopic submucosal dissection strategy.

- Citation: Wang J, Chang L, Niu DF, Yan Y, Cao CQ, Li SJ, Wu Q. Diagnostic accuracy of stereomicroscopy assessment of invasion depth in ex vivo specimens of early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(45): 112518

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i45/112518.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.112518

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a cornerstone of early gastric cancer (EGC) management, enabling minimally invasive curative resection of mucosal and superficial submucosal lesions[1-3]. Postoperative pathological evaluation of ESD specimens is crucial for determining therapeutic adequacy, as the invasion depth, margin status, and ulceration directly guide clinical decisions regarding adjuvant therapy and follow-up strategies[4]. When assessing invasion depth, especially for lesions with submucosal infiltration, sectioning at the deepest point of infiltration during specimen pre

In this context, stereomicroscopy is being recognized as an invaluable tool in the pathological evaluation of tissue specimens, especially in the case of small biopsies and surgical resections[6,7]. This imaging technique provides distinct advantages, including three-dimensional visualization and enhanced depth perception, both of which are crucial for accurately assessing the characteristics of lesions and their relationships within complex tissue architecture[8,9]. Previous studies demonstrated that stereomicroscopy can achieve complete one-to-one correspondence between endoscopic and histopathological images, making it a powerful tool for bridging endoscopy and histopathology[10,11]. For EGC spe

This study utilized stereomicroscopy to comprehensively evaluate postoperative ESD specimens. This approach aimed to enhance the assessment of lesion depth, extent, and adjacent minute pathological features. Based on the stereomicroscopy results, targeted tissue sampling and precise histological analysis were performed. The primary goal was to assess the diagnostic performance of stereomicroscopy in determining the invasion depth of EGC using postoperative pathological outcomes as the reference standard.

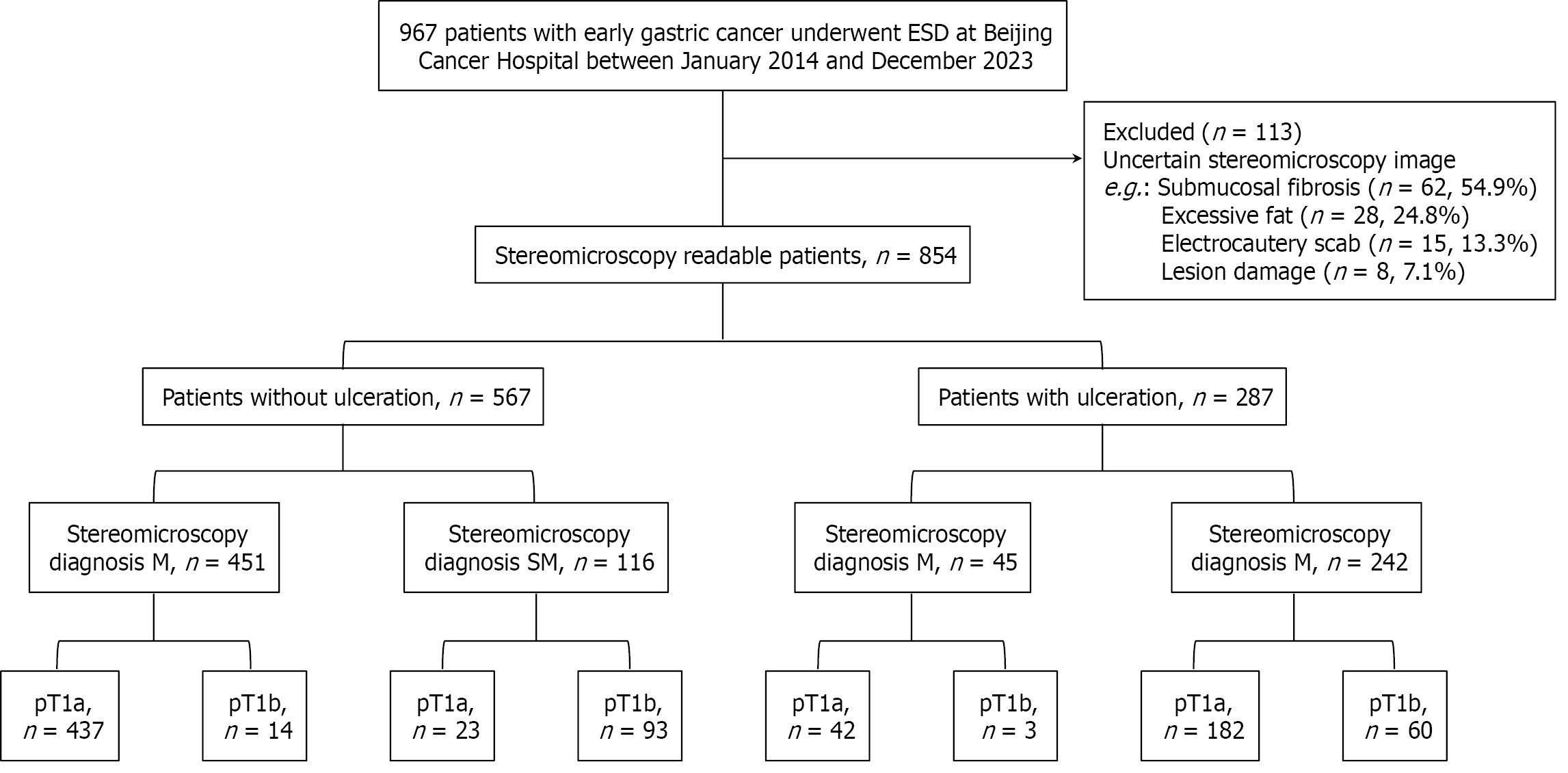

We retrospectively studied samples from 967 patients with EGC who underwent ESD at Peking University Cancer Hospital from 2014 to 2023. All patients underwent preoperative endoscopic ultrasound and abdominal computed tomography, which revealed no lymph node metastasis (cT1N0). After multidisciplinary evaluation, ESD was performed, and postoperative pathology confirmed the diagnosis of EGC. Of these patients, 113 (11.7%) were excluded because of technical issues, including submucosal fibrosis (54.9%), excessive fat (24.8%), electrocautery artifacts (13.3%), and specimen fragmentation (7.1%, Supplementary Table 1).

The remaining patients with EGC were divided into two groups according to the absence (567 patients) and presence of ulceration (287 patients). Stereomicroscopic diagnosis was based on submucosal appearance: Stereomicroscopy-M for uniformly thick, transparent tissue, and stereomicroscopy-SM for lesions showing the “Basal White Sign”, a localized, opaque, whitish area > 5 mm in diameter, which served as the key objective indicator of invasion. Each subgroup was then histologically classified as pT1a (tumors confined to the mucosa) or pT1b (tumors invading the submucosa but not beyond, per the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma, 15th edition). Finally, we evaluated the accuracy of stereomicroscopy in diagnosing tumor invasion depth and analyzed the clinicopathological features of misdiagnosed EGCs (Figure 1).

The endoscope and accessories for pre-ESD examinations were obtained from Olympus Optical Co., Ltd (Tokyo, Japan), including the CV-260SL main unit, GIF-H260Z endoscope, and MAJ-1890 transparent cap. During ESD, instruments such as the CV-260SL main unit; GIF-H260Z, GIF-Q260J, and GIF-2QT260M endoscopes; D-201-12402, D-201-11804, and D-201-13404 transparent caps; NM-200 L-0423 injection needle; KD-650 L Dual Knife; KD-611 L IT Knife; FD-410 LR hemostatic forceps; and HX-610-135 metal clips were used. A VIO 200S high-frequency electric device (Erbe Elektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) was also used. An SZX7 optical microscope (Olympus, Japan) was used to evaluate postoperative specimens.

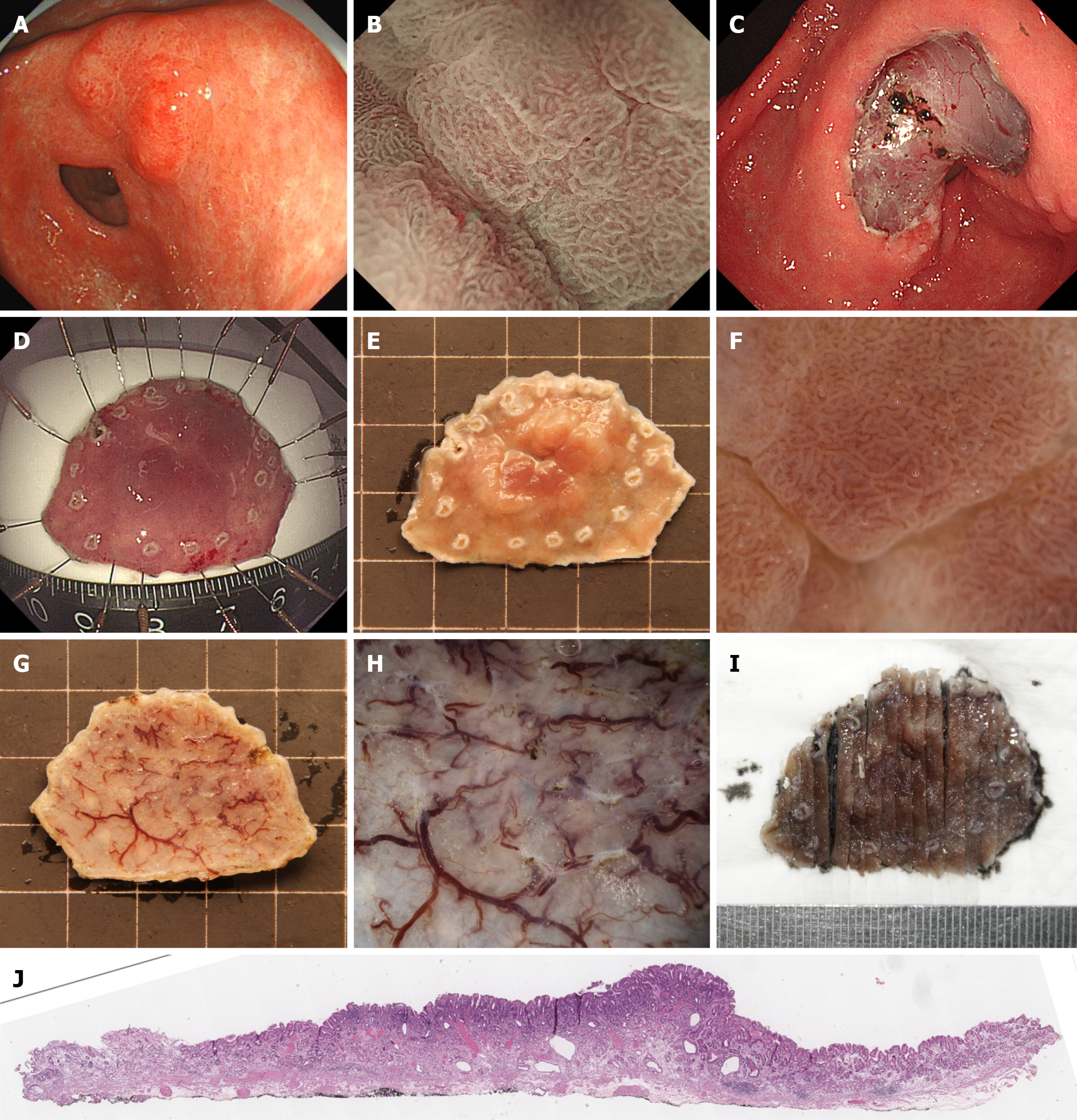

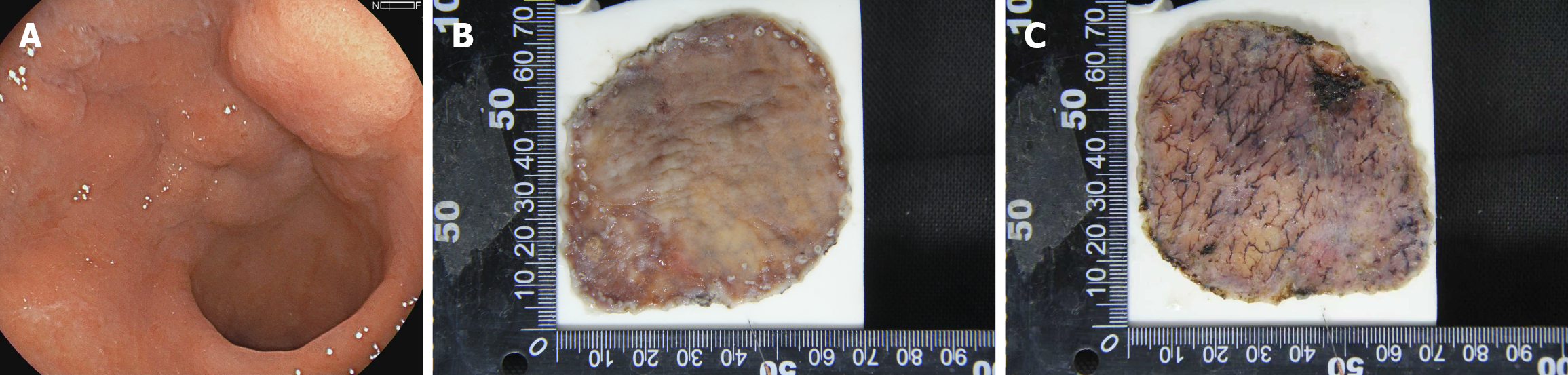

Preoperative lesion evaluation was performed using a GIF-H260Z magnifying endoscope. The endoscopist, who was blinded to the pre-biopsy results, assessed microsurface structure loss. The Sakita-Fukutomi system was used to grade gastroscopy-observed ulcers. Premalignant biopsy-induced ulcers were excluded by defining microsurface structure loss as an unstructured area larger than 4 mm[12]. Lesions were first examined with a magnified endoscope and then stained with indigo and carmine to enhance visibility. All endoscopic images were captured and stored in BMP and JPEG formats at 640 × 480 pixels and 72 DPI (Figures 2 and 3).

An experienced endoscopist, who performs approximately 100 ESD procedures annually, conducted ESD under general anesthesia. Using an upper gastrointestinal endoscope (GIF Q260J) with a transparent cap, the procedure followed a systematic process: Marking the lesion, injecting the submucosa, incising the mucosa, and dissecting the submucosa. Two extra marking points were added to define the oral and anal margins of the lesion (Figure 2).

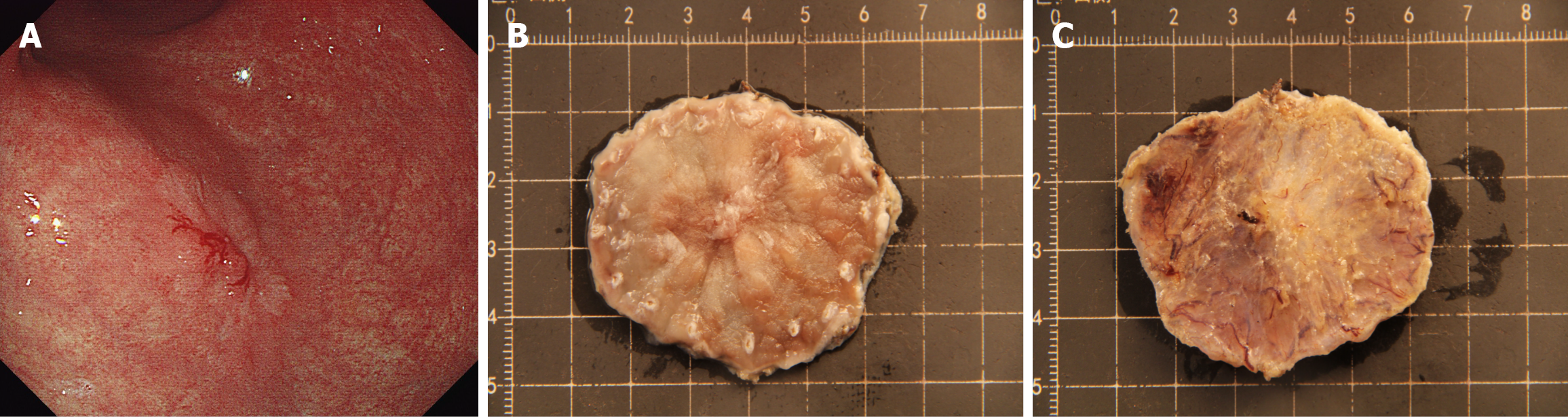

Specimen fixation was conducted utilizing fixation needles to firmly secure the ESD-resected specimen onto a specimen fixation board, and the oral and anal boundaries of the lesion were clearly demarcated (Figure 2). Subsequently, the specimen was immersed in formalin solution for 24 hours to ensure adequate fixation. After fixation, any secretions present on the mucosal surface were meticulously removed. The specimen was then fully submerged in water to minimize reflections, thereby facilitating optimal observation with an SZX7 stereomicroscope (Figures 2 and 3) equipped with a 150-W fiber-optic light source and adjustable magnification (× 0.8-5.6).

Specimens were systematically examined under the stereomicroscope, beginning at low magnification and incrementally increasing to high magnification. Microsurface and microvascular patterns were analyzed using diagnostic criteria identical to those applied during preoperative magnified endoscopy. Proximal-to-horizontal (lateral) resection borders were identified to guide incision planning. Additionally, the vertical (basal) margins were meticulously assessed to evaluate submucosal invasion depth and resection completeness, both examining the microsurface and recording the diameter of the thickest vessel at the basal surface. To evaluate intraobserver and interobserver reproducibility, the cases was re-evaluated by the same endoscopist and by a second independent endoscopist. Cohen’s kappa (κ) was calculated.

Following the stereomicroscopic examination and final histopathological assessment, cases with discrepant findings between the two methods were identified as misdiagnosed cases. These misdiagnosed cases were specifically re-evaluated to analyze the potential reasons for the diagnostic discrepancy. The stereomicroscopic images and corresponding histopathological slides of these cases were thoroughly reviewed by the endoscopists and pathologists in conjunction. Images of the lesions observed under the stereomicroscope were captured using a connected DSLR camera (EOS 60D, Canon, Tokyo, Japan) and saved in the BMP and JPEG formats at a resolution of 1280 × 1000 pixels with a DPI of 72.

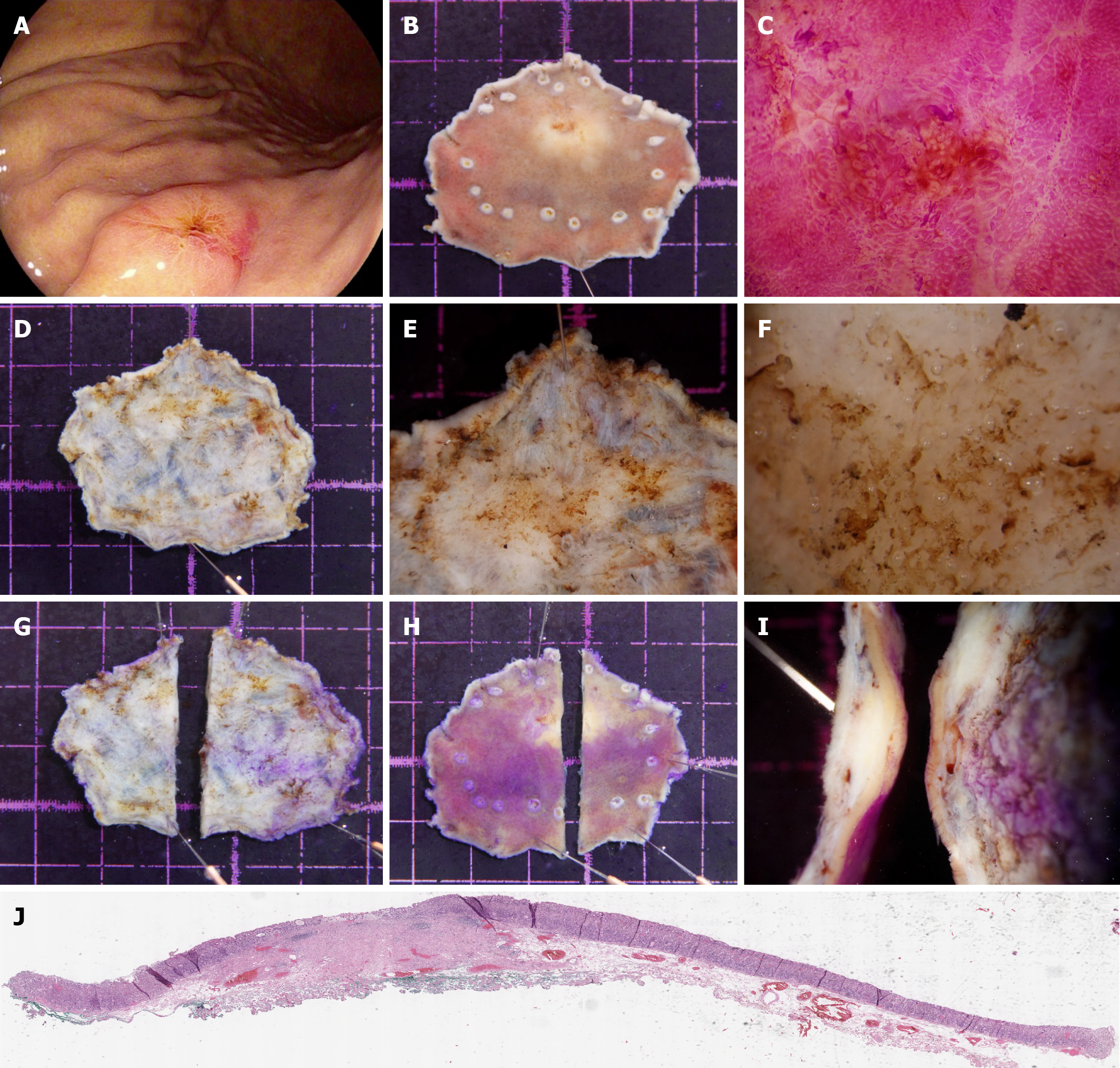

Two senior gastrointestinal pathologists independently conducted the histopathological assessment while masked to the stereomicroscopy results. Disagreements on the classification (pT1a vs pT1b) were resolved by discussion or consultation with a third senior pathologist when consensus could not be reached. Serial sections were taken every 2 mm perpendicular to the lateral resection margin identified by stereomicroscopy, aligning with the nearest horizontal margin for accurate histologic correlation (Figure 2). For specimens with suspected submucosal infiltration based on the stereomicroscopic findings, the initial incision was made away from the suspected invasion site on the basal surface. A precise incision was then performed 1 mm from the deepest infiltration point to account for potential tissue loss during slicing (Figure 3). Pathologists evaluated the specimens for tumor characteristics, including size, macroscopic type, histological type, invasion depth, ulceration or scarring, and horizontal/vertical margins, as well as lymphatic and vascular infiltration, to assess ESD curability (Figures 2 and 3). A pathological ulcer was defined as a mucosal defect extending beyond the muscularis mucosae, corresponding to at least ultra-local-II in depth per Japanese guidelines, ensuring clinical relevance[13].

For specimens with confirmed submucosal invasion (pT1b), we evaluated the accuracy of stereomicroscopy in identifying the deepest invasion point. The assessment was considered correct when the stereomicroscopy-identified deepest point matched the histologically confirmed deepest infiltration site within a 1-mm margin. Patients were excluded from this analysis if the pathological sectioning photographs were unavailable, precluding reliable determination of correspondence.

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous data, expressed as mean ± SD or quartiles, were compared using t-tests or nonparametric tests. Associations among categorical variables in clinical characteristic comparisons were assessed using the χ2 test, continuity correction, or Fisher’s exact test. Multivariate comparisons were conducted using binary logistic regression. P < 0.05 was considered statistically signi

Table 1 presents the clinicopathological features of the patients and their lesions. The cohort included 627 men and 227 women with a mean age of 62 years. Lesions were distributed as follows: 233 in the upper stomach, 279 in the middle stomach, 325 in the lower stomach, and 17 in the residual stomach. Macroscopic types included 51 type 0-I, 362 type 0-IIa, 39 type 0-IIb, 390 type 0-IIc, and 12 type 0-III lesions. The tumor sizes were ≤ 20 mm, 21-30 mm, and > 31 mm for 508, 207, and 139 lesions, respectively. Ulceration was absent in 567 lesions and present in 287 lesions. The histological type was differentiated in 704 lesions and undifferentiated in 150 lesions. Horizontal margins were negative in 830 lesions and positive in 24 lesions, whereas vertical margins were negative in 790 lesions and positive in 64 lesions.

| Variables | 854 patients |

| Sex | |

| Male | 627 (73.4) |

| Female | 227 (26.6) |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 62.0 ± 9.8 |

| Location | |

| Upper1 | 233 (27.2) |

| Middle2 | 279 (32.7) |

| Lower3 | 325 (38.1) |

| Residual stomach | 17 (2.0) |

| Macroscopic type | |

| Type 0-I | 51 (6.0) |

| Type 0-IIa | 362 (42.4) |

| Type 0-IIb | 39 (4.6) |

| Type 0-IIc | 390 (45.6) |

| Type 0-III | 12 (1.4) |

| Tumor size (mm) | |

| ≤ 20 | 508 (59.5) |

| 21-30 | 207 (24.2) |

| > 31 | 139 (16.3) |

| Ulceration | |

| (−) | 567 (66.4) |

| (+) | 287 (33.6) |

| Histopathological type | |

| Differentiated | 704 (82.4) |

| Undifferentiated | 150 (17.6) |

| Horizontal margin | |

| (−) | 830 (97.2) |

| (+) | 24 (2.8) |

| Vertical margin | |

| (−) | 790 (92.5) |

| (+) | 64 (7.5) |

The overall diagnostic accuracy of stereomicroscopy is summarized in Table 2. In the non-ulceration group, stereomicroscopy achieved a diagnostic accuracy of 93.5% [95% confidence interval (CI): 91.1-95.4], compared with 35.8% (95%CI: 30.2-41.6) in the ulceration group. Of the 567 lesions with ulceration, 451 were categorized as mucosal lesions on stereomicroscopy. Of these, the lesions types on histopathology were T1a and T1b in 437 and 14 patients, respectively. Of the 116 lesions were by stereomicroscopically categorized as submucosal lesions, the lesion type on histopathology was T1a for 23 patients and T1b for 93 patients. This resulted in sensitivity of 95.0% (95%CI: 92.6-96.8), specificity of 86.9% (95%CI: 79.0-92.7), positive predictive value of 96.9% (95%CI: 95.0-98.0), negative predictive value of 80.2% (95%CI: 73.0-85.8), and diagnostic accuracy of 93.5% (95%CI: 91.1-95.4).

| Stereomicroscopy diagnosis | Pathological stage | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | |

| T1a | T1b | ||||||

| Ulceration absent | NA | NA | 93.5 | 95.0 | 86.9 | 96.9 | 80.2 |

| M | 437 | 14 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| SM | 23 | 93 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ulceration present | NA | NA | 35.8 | 19.1 | 95.2 | 93.5 | 24.8 |

| M | 42 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| SM | 182 | 60 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Among the 287 lesions with ulceration, 45 were categorized as mucosal lesions on stereomicroscopy (42 T1a and 3 T1b lesions on histopathology), and 242 were categorized as submucosal lesions (182 T1a and 60 T1b lesions on histopatho

Table 3 presents the clinicopathological features of gastric cancers accurately and inaccurately diagnosed by stereomicroscopy. Ulceration was more common in the misdiagnosed group (64.5%, 185/287) than in the accurately diagnosed group (35.5%, 102/287; P < 0.001). The difference in tumor size between these groups was also significant (P < 0.05). Table 4 Lists the risk factors for stereomicroscopy misdiagnosis. Multivariate analysis revealed that lower tumor location [odds ratio (OR) = 0.6, 95%CI: 0.448-0.937] and positive vertical margins (OR = 0.1, 95%CI: 0.025-0.221) were independent protective factors. Tumor size of 21-30 mm (OR = 1.6, 95%CI: 1.011-2.695) and the presence of ulceration (OR = 36.1, 95%CI: 22.728-57.40) were independent risk factors for misdiagnosis. Representative images of two misdiagnosed cases are provided in Figures 4 and 5.

| Factors | Stereomicroscopy diagnosis | P value | |

| Accurately, n = 632 | Misdiagnosed, n = 222 | ||

| Location | |||

| Upper | 168 (72.1) | 5 (27.9) | 0.113 |

| Middle | 196 (70.3) | 83 (29.7) | |

| Lower | 255 (78.5) | 70 (21.5) | |

| Residual stomach | 13 (76.5) | 4 (23.5) | |

| Macroscopic type | |||

| Type 0-I | 42 (82.4) | 9 (17.6) | 0.179 |

| Type 0-IIa | 276 (76.2) | 86 (23.8) | |

| Type 0-IIb | 30 (76.9) | 9 (23.1) | |

| Type 0-IIc | 277 (71.0) | 113 (29.0) | |

| Type 0-III | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | |

| Tumor size (mm) | |||

| ≤ 20 | 404 (79.5) | 104 (20.5) | < 0.001 |

| 21-30 | 138 (66.7) | 69 (33.3) | |

| > 31 | 90 (64.7) | 49 (35.3) | |

| Ulceration | |||

| (−) | 530 (93.5) | 37 (6.5) | < 0.001 |

| (+) | 102 (35.5) | 185 (64.5) | |

| Histopathological | |||

| Differentiated | 518 (73.7) | 185 (26.3) | 0.645 |

| Undifferentiated | 114 (75.5) | 37 (24.5) | |

| Horizontal margin | |||

| (−) | 613 (73.9) | 217 (26.1) | 0.559 |

| (+) | 19 (79.2) | 5 (20.8) | |

| Vertical margin | |||

| (−) | 573 (72.5) | 217 (27.5) | < 0.001 |

| (+) | 59 (92.2) | 5 (7.8) | |

| Factors | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Location | |||

| Middle | 1 | Reference | |

| Upper | 0.9 | 0.622-1.342 | 0.645 |

| Lower | 0.6 | 0.448-0.937 | 0.021 |

| Residual stomach | 0.7 | 0.230-2.294 | 0.586 |

| Macroscopic type | |||

| Type 0-I | 1 | Reference | |

| Type 0-IIa | 0.4 | 0.173-1.122 | 0.086 |

| Type 0-IIb | 0.4 | 0.11-1.681 | 2.225 |

| Type 0-IIc | 0.5 | 0.189-1.218 | 0.122 |

| Type 0-III | 0.2 | 0.044-1.022 | 0.053 |

| Tumor size (mm) | |||

| ≤ 20 | 1 | Reference | |

| 21-30 | 1.6 | 1.011-2.695 | 0.045 |

| ≥ 31 | 1.5 | 0.826-2.575 | 0.193 |

| Ulceration | |||

| (−) | 1 | Reference | |

| (+) | 36.1 | 22.728-57.40 | < 0.001 |

| Histopathological | |||

| Differentiated | 1 | Reference | |

| Undifferentiated | 0.7 | 0.417-1.345 | 0.333 |

| Horizontal margin | |||

| (−) | 1 | Reference | |

| (+) | 0.7 | 0.186-2.742 | 0.624 |

| Vertical margin | |||

| (−) | 1 | Reference | |

| (+) | 0.1 | 0.025-0.221 | < 0.001 |

We analyzed the relationship between the maximum basal vessel diameter measured by stereomicroscopy and the pathological invasion depth. The mean vessel diameter was significantly larger in submucosal lesions (663.6 ± 258.9 μm, n = 136) than in mucosal lesions (505.5 ± 241.3 μm, n = 585; P < 0.001). This objective parameter provides quantitative support for the qualitative assessment of submucosal invasion based on tissue architecture changes.

We further evaluated the clinical utility of stereomicroscopy in guiding precise pathological sampling for the 170 specimens with confirmed submucosal invasion (pT1b). Among these, seven specimens (4.1%) were excluded because of the unavailability of pathological sectioning photographs, which prevented definitive determination of the correspondence between the stereomicroscopy-guided site and the histological deepest point. In the remaining 163 evaluable T1b lesions, stereomicroscopy correctly guided the incision to the deepest invasion point in 152 patients, corresponding to an accuracy of 93.3% (95%CI: 88.2-96.5).

The reproducibility of the stereomicroscopic assessment was evaluated by analyzing both interobserver and intraobserver agreement. The interobserver agreement for stereomicroscopic classification (mucosal vs submucosal) across all 854 evaluable patients was almost perfect, with κ of 0.816 (95%CI: 0.777-0.855). Furthermore, the intraobserver agreement demonstrated excellent reproducibility (κ = 0.879, 95%CI: 0.848-0.914). These high agreement levels confirm the reliability and consistency of stereomicroscopic assessment among trained operators.

Our study demonstrated that stereomicroscopic evaluation of ESD specimens achieved high diagnostic accuracy for the depth of invasion in the overall cohort (74.0%), with particularly robust performance in non-ulcerated lesions (accuracy = 93.5%). For non-ulcerated EGC specimens, stereomicroscopic examination of the specimen base enabled reliable predic

Our investigation also identified critical clinicopathological features associated with diagnostic errors. Tumor size of 21-30 mm and the presence of ulceration emerged as independent risk factors for misdiagnosis. This finding aligns with established evidence that a larger tumor diameter in EGC is associated with lymph node metastasis and adverse oncologic outcomes, potentially indicating submucosal infiltration and thus contributing to staging uncertainty[15,16]. Upon ulcer formation, significant changes in mucosal tissue occur, complicating the submucosal dissection process. The increased vascularity surrounding ulcerated lesions might lead to excessive bleeding, thereby complicating the obser

Conversely, the probability of misdiagnosis was lower for tumors located in the lower third of the stomach. This finding likely reflects the technical ease of managing these lesions during ESD. The relatively straightforward vascular anatomy of the lower third of the stomach reduces intraprocedural bleeding risk compared with that of upper two-thirds of these stomachs, in which tortuous vasculature necessitates frequent hemostatic interventions (e.g., electrocautery)[19,20]. Consequently, limited thermal injury in the lower third of the stomach preserves native submucosal architecture, enabling clearer stereomicroscopic visualization and more accurate invasion depth assessment.

Notably, lesions with positive vertical margins exhibited distinct histologic characteristics that minimized diagnostic ambiguity. The presence of well-defined vertical margins is often correlated with tumors situated in anatomically accessible regions, enhancing pathologic visualization of critical invasion-related features. However, stereomicroscopic identification of submucosal invasion warrants cautious histologic sampling: Regions flagged for submucosal invol

Our finding of significantly larger basal vessel diameters in submucosal lesions (663.6 μm vs 505.5 μm, P < 0.0001) provides an objective quantitative parameter that complements the qualitative assessment of tissue architecture. This observation might reflect the angiogenic changes associated with tumor progression and invasion, as deeper infiltrating lesions require more substantial vascular support. The integration of such measurable parameters could enhance the diagnostic algorithm for invasion depth assessment, particularly in borderline cases in which qualitative features are ambiguous.

Chen et al[21] illustrated that optical-assisted pathology can enhance the specificity and accuracy of pathological diagnoses. However, their study predominantly focused on the evaluation of lesion margins and microvascular struc

By contrast, our stereomicroscopy-based approach for evaluating post-ESD specimens establishes an efficient and practical communication bridge between endoscopists and pathologists. To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically assess invasion depth in EGC using stereomicroscopic examination of ESD specimens, including novel vertical margin (basal aspect) evaluation. By correlating stereomicroscopic images with preoperative endoscopic visuals and final histopathology, this method provides pathologists with targeted sampling guidance, improving diagnostic efficiency and precision. Statistical validation confirmed that stereomicroscopy enhances the pathological determination of invasion depth (accuracy: 93.5% in non-ulcerated vs 35.8% in ulcerated lesions), directly addressing limitations of prior methodologies.

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, the exclusion of technically challenging specimens (e.g., those with severe submucosal fibrosis, accounting for 11.7% of cases) constitutes a technical limitation of stereomicroscopy and underscores the need for integrating ancillary techniques, such as elastin staining or digital pathology, to augment diagnostic reliability in complex scenarios. Second, the extended study period and operator-dependent variables (e.g., variations in ESD expertise, hemostatic forceps utilization frequency) might have introduced confounding effects, particularly in fibrosis assessment. Third, the single-center retrospective design inherently limited generalizability. Future multicenter prospective validation is essential, especially in Western populations in which undifferentiated histology predominates. Finally, although we plan to incorporate objective metrics (e.g., maximum basal vessel diameter) with microsurface features to refine invasion depth assessment, this requires rigorous validation in ongoing analyses.

This study demonstrated its principal strength through a translational framework that correlated stereomicroscopic features, such as localized submucosal thickening and opacity gradients, with endoscopic and histopathological findings. This approach establishes a practical protocol for targeted tissue sampling, significantly reducing pathologists' work

The authors thank the Department of Pathology, Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute (Beijing, China) for its support. We also acknowledge the expert procedural assistance provided by Liu Y of the endoscopy nursing team.

| 1. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2021 (6th edition). Gastric Cancer. 2023;26:1-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 842] [Article Influence: 280.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Lordick F, Carneiro F, Cascinu S, Fleitas T, Haustermans K, Piessen G, Vogel A, Smyth EC; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022;33:1005-1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 911] [Article Influence: 227.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang FH, Zhang XT, Tang L, Wu Q, Cai MY, Li YF, Qu XJ, Qiu H, Zhang YJ, Ying JE, Zhang J, Sun LY, Lin RB, Wang C, Liu H, Qiu MZ, Guan WL, Rao SX, Ji JF, Xin Y, Sheng WQ, Xu HM, Zhou ZW, Zhou AP, Jin J, Yuan XL, Bi F, Liu TS, Liang H, Zhang YQ, Li GX, Liang J, Liu BR, Shen L, Li J, Xu RH. The Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO): Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer, 2023. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2024;44:127-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 108.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Uedo N, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Fujimoto K. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer (second edition). Dig Endosc. 2021;33:4-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 72.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Kumarasinghe MP, Bourke MJ, Brown I, Draganov PV, McLeod D, Streutker C, Raftopoulos S, Ushiku T, Lauwers GY. Pathological assessment of endoscopic resections of the gastrointestinal tract: a comprehensive clinicopathologic review. Mod Pathol. 2020;33:986-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nakatani S, Okuwaki K, Watanabe M, Imaizumi H, Iwai T, Matsumoto T, Hasegawa R, Masutani H, Kurosu T, Tamaki A, Ishizaki J, Ishizaki A, Kida M, Kusano C. Stereomicroscopic on-site evaluation in endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition of upper gastrointestinal subepithelial lesions. Clin Endosc. 2024;57:89-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shah PU, Mane DR, Angadi PV, Hallikerimath SR, Kale AD. Efficacy of stereomicroscope as an aid to histopathological diagnosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:356-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Horvath S, Macdonald K, Galeotti J, Klatzky RL. Slant Perception Under Stereomicroscopy. Hum Factors. 2017;59:1128-1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rodriguez-Palacios A, Kodani T, Kaydo L, Pietropaoli D, Corridoni D, Howell S, Katz J, Xin W, Pizarro TT, Cominelli F. Stereomicroscopic 3D-pattern profiling of murine and human intestinal inflammation reveals unique structural phenotypes. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fujita Y, Kishimoto M, Dohi O, Kamada K, Majima A, Kimura-Tsuchiya R, Yagi N, Konishi H, Naito Y, Harada Y, Tanaka H, Konishi E, Sugai T, Yanagisawa A. How to adjust endoscopic findings to histopathological findings of the stomach: a "histopathology-oriented" correspondence method helps to understand endoscopic findings. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:573-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Majima A, Kishimoto M, Dohi O, Fujita Y, Morinaga Y, Yoshimura R, Ishida T, Kamada K, Konishi H, Naito Y, Itoh Y, Konishi E. Complete one-to-one correspondence between magnifying endoscopic and histopathologic images: the KOTO method II. Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:1365-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Park YS, Kook MC, Kim BH, Lee HS, Kang DW, Gu MJ, Shin OR, Choi Y, Lee W, Kim H, Song IH, Kim KM, Kim HS, Kang G, Park DY, Jin SY, Kim JM, Choi YJ, Chang HK, Ahn S, Chang MS, Han SH, Kwak Y, Seo AN, Cho MY. A standardized pathology report for gastric cancer: 2nd edition. J Pathol Transl Med. 2023;57:1-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2950] [Article Influence: 196.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med. 2012;18:1028-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2470] [Cited by in RCA: 2790] [Article Influence: 199.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Paredes O, Baca C, Cruz R, Paredes K, Luque-Vasquez C, Chavez I, Taxa L, Ruiz E, Berrospi F, Payet E. Predictive factors of lymphatic metastasis and evaluation of the Japanese treatment guidelines for endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer in a high-volume center in Perú. Heliyon. 2023;9:e16293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liu DY, Hu JJ, Zhou YQ, Tan AR. Analysis of lymph node metastasis and survival prognosis in early gastric cancer patients: A retrospective study. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2024;16:1637-1646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim YJ, Park DK. Management of complications following endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang J, Shan F, Li S, Li Z, Wu Q. Effect of administration of a proton pump inhibitor for ulcerative differentiated early gastric cancer prior to endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2021;33:939-947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Saito I, Tsuji Y, Sakaguchi Y, Niimi K, Ono S, Kodashima S, Yamamichi N, Fujishiro M, Koike K. Complications related to gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection and their managements. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:398-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mannen K, Tsunada S, Hara M, Yamaguchi K, Sakata Y, Fujise T, Noda T, Shimoda R, Sakata H, Ogata S, Iwakiri R, Fujimoto K. Risk factors for complications of endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric tumors: analysis of 478 lesions. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chen G, Xu R, Yue B, Jia M, Li P, Ji M, Zhang S. A Parallel Comparison Method of Early Gastric Cancer: The Light Transmission-Assisted Pathological Examination of Specimens of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection. Front Oncol. 2021;11:705418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhao Y, Wang H, Fan Y, Jin C, Xu Q, Jing J, Zhang T, Zhang X, Chen W. A mucosal recovery software tool for endoscopic submucosal dissection in early gastric cancer. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1001383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dostler I, Ell C, Neuhaus H, Stolte M. Diagnosis of early neoplasia in Barrett's mucosa based on changes in surface structure. Comparative stereo-microscopic and histological investigations in 600 endoscopically resected specimens. Z Gastroenterol. 2010;48:542-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ebigbo A, Probst A, Messmann H, Märkl B, Nam-Apostolopoulos YC. Topographic mapping of a specimen after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E521-E524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/