Published online Dec 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.112436

Revised: September 1, 2025

Accepted: October 13, 2025

Published online: December 7, 2025

Processing time: 129 Days and 15.4 Hours

The management of biliary strictures is challenging both diagnostically and thera

Core Tip: The optimal diagnostic and therapeutic approach to the management of biliary strictures utilizes endoscopic ultrasound and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. This review highlights existing evidence to guide clinicians in the management of biliary strictures, focusing on the benefits of performing both procedures in the same session. Two algorithms are presented to standardize patient care by personalizing the approach based on individual patient factors and institutional expertise.

- Citation: Pacheco-Cassamá J, Monteiro S, Silva J. Two scopes, one mission: An integrated approach of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasound to biliary strictures. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(45): 112436

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i45/112436.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.112436

A biliary stricture is defined as a narrowing of either the intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts, or both. It frequently leads to obstruction of bile flow, typically resulting in upstream biliary dilation[1] and bile accumulation, leading to signs and symptoms, such as jaundice, anorexia, dark urine, and pruritus, as well as biochemical abnormalities, including a cholestatic pattern in liver function tests[2]. Persistent biliary stricture can lead to complications like ascending cholangitis, gram-negative septicemia, and hepatic abscesses, which are linked to high rates of morbidity and mortality[3].

A spectrum of causes is associated with these strictures, classified as benign or malignant[4,5]. The diagnostic challenge lies in distinguishing between benign and malignant etiologies. Advances in medical technology have replaced more invasive diagnostic procedures with techniques associated with lower morbidity[2,5-7]. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) allows for biliary drainage and tissue sampling via brush cytology or forceps biopsy. Nevertheless, its diagnostic yield is low and carries potential risks, including post-ERCP pancreatitis[8]. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has emerged as a complementary tool, providing high-resolution imaging of the biliary tree and surrounding structures. It enables tissue acquisition (TA) through fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and/or fine-needle biopsy (FNB) and plays an increasingly important role in therapeutic biliary drainage, especially when ERCP fails[9-12].

This review explores strategies for the diagnosis and treatment of biliary strictures, focusing on the complementary roles of EUS and ERCP.

Malignant biliary strictures (MBSs) are more frequent than benign biliary strictures (BBSs), and are caused by primary or secondary/metastatic tumors. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma are the most common primary causes[13,14]. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is particularly aggressive, being often diagnosed at a late stage. Approximately 60%-70% of pancreatic cancers form in the head of the pancreas, frequently causing biliary obstruction. Up to 70% of patients presenting with pancreatic cancer are estimated to already have a biliary stricture at the time of diagnosis[13,15,16]. Cholangiocarcinoma, although relatively rare, has a poor prognosis due to being asymptomatic in its early stages[17], with an estimated survival of 12 months for patients with unresectable disease who undergo systemic treatment[18]. Other primary tumors, such as gallbladder cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, ampulloma, primary duodenal adenocarcinoma, and lymphoproliferative disorders, have lower incidences[2,19]. Secondary or metastatic causes include widespread colon, breast, and renal cell cancers[20]. BBSs are most frequently caused by iatrogenic injury (especially following cholecystectomy or liver transplantation) and fibroinflammatory conditions[21]. BBSs following cho

| Most common etiologies | |

| Benign | Post-operative or iatrogenic (e.g., after cholecystectomy, liver transplantation) |

| Pancreatitis (chronic) | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | |

| IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis | |

| Other: Trauma, recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, AIDS cholangiopathy, ischemia, primary biliary cirrhosis, Mirizzi syndrome, medications | |

| Malignant | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | |

| Metastatic tumors (renal cell cancer, breast cancer, colon cancer) | |

| Other: Gallbladder malignancy, ampulloma, primary duodenal adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, lymphoma, neuroendocrine tumors |

The etiology of biliary strictures and their locations determine both the urgency and the technique of the diagnostic approach. Biliary strictures are classified as intrahepatic, perihilar, or extrahepatic (distal). Extrahepatic (distal) strictures are the most common and typically result from malignancy. Perihilar strictures are frequently caused by hilar cholangiocarcinoma, but benign etiologies such as PSC and postoperative injury may occur, particularly after liver transplantation. Perihilar strictures are less common than distal malignant strictures but represent a significant clinical problem[2,3,25]. Intrahepatic strictures are most often associated with benign diseases such as PSC, immunoglobulin G4-related sclerosing cholangitis, and recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. Malignancy is less common in this location[3,28].

When a biliary stricture is suspected (based on clinical presentation, initial abdominal ultrasound, and laboratory tests), cross-sectional imaging is essential for an accurate evaluation. Magnetic resonance imaging with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is the modality of choice. This provides detailed anatomical information, helps determine the level of the stricture, distinguishes between etiologies, and assists in staging and assessing resectability when malignancy is suspected[20,29].

ERCP enables visualization of the stricture and enables TA via brush cytology and forceps biopsy[2]. Brush cytology is a common method to obtain a tissue sample; here, a specially designed brush is used to collect cellular material from the mucosa, which is then analyzed under a microscope. Its sensitivity for detecting malignancy is suboptimal, particularly due to insufficient cellular sampling. A 2015 meta-analysis conducted by Navaneethan et al[30] found that the sensitivity of brush cytology was 45% and specificity was 99% for the diagnosis of MBSs. A combination of brush cytology with forceps biopsy is an alternative to enhance the diagnostic yield. This technique is used during ERCP to take tissue samples (typically 1 to 3 specimens, although the optimal number of biopsy specimens for diagnosis has not yet been established)[31], and it is considered more time-consuming and complex than brushing. When performed alone, forceps biopsy has a sensitivity for malignancy ranging from 48% to 52%, while specificity is consistently higher than 99%[2,32,33]. Combining brush cytology with forceps biopsy increases overall sampling sensitivity to 59.4%-66% and specificity to 100%[32]. These two techniques have a synergistic role in enhancing the accuracy of tissue diagnosis in biliary strictures. However, ERCP-based TA (ERCP-TA) has limited sensitivity, and adjunctive modalities and/or more advanced technologies[34] may be required to further improve diagnostic performance. Cholangioscopy, mainly direct peroral cholangioscopy (DPC), offers direct intraductal visualization and targeted biopsies via ERCP, as it enables additional direct endoscopic visualization of the biliary duct in addition to fluoroscopic imaging. Tissue sampling relies on biopsies under direct vision - 4 to 6 bites with SpyBite biopsy forceps are recommended to improve diagnostic yield[35]. Cholangioscopy-guided biopsies have superior sensitivity (up to 76.5%) compared to brushings and standard biopsies[34,36,37]. The overall adverse event rate (cholangitis, pancreatitis, hemobilia, bile leak, air embolism, and bile duct perforation) ranges from 2% to 30%[38]. The overall rate of adverse events is similar between ERCP with and without DPC, but the DPC group has a higher proportion of severe complications. In a comparative study, 16 of 81 patients undergoing ERCP with DPC developed adverse events (including 2 cases of severe pancreatitis and 1 case of severe bleeding), whereas 21 of 72 patients undergoing ERCP without DPC experienced only mild adverse events[32]. DPC is more technically demanding in distal strictures due to scope instability in the periampullary region, and an increased risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis with cholangioscopy compared to ERCP alone is supported by large registry data. However, cited literature does not directly link higher pancreatitis risk specifically to distal strictures[32,39]. Overall sensitivity for malignant strictures may be similar to or even lower than forceps biopsy’s sensitivity in distal biliary strictures[32]. Therefore, DPC is generally preferred in non-distal strictures. Over the years, ERCP has primarily evolved into a therapeutic tool. This change is due to the development of noninvasive imaging techniques like MRCP and EUS, offering detailed ductal imaging without the risks associated with ERCP, such as pancreatitis, perforation, or ascending cholangitis[8].

EUS allows high-resolution imaging and facilitates TA of biliary strictures or adjacent masses, with reported higher diagnostic yield in detecting malignancy than ERCP-based brushings, forceps biopsies, or cholangioscopy. EUS-based TA (EUS-TA) includes EUS-guided FNA (EUS-FNA), which collects cells or fluid for cytology, histology, or fluid analysis, and EUS-guided FNB (EUS-FNB), which retrieves core tissue for histological evaluation. EUS-TA has an estimated sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 97%[40-42] and is generally preferred over ERCP-TA in distal strictures when a mass is present. However, in perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, EUS-TA is discouraged in transplant candidates due to the risk of needle tract seeding that may preclude liver transplantation[32]. EUS-FNB is similar to EUS-FNA but uses a larger needle to obtain core biopsies. Early-generation FNB needles were technically challenging to use and not clearly superior to FNA needles; however, newer-generation devices show higher tissue adequacy, fewer passes required, and provide improved diagnostic yield[43]. In a randomized crossover trial in 108 patients with solid pancreatic masses, fork-tip FNB (with two sharp tips) achieved higher sensitivity (82% vs 71%) and accuracy (84% vs 75%) compared with FNA, while also reducing procedure and pathology assessment times[44]. Similarly, a study with 46 patients reported that Franseen FNB needle (with three cutting edges) provided better tissue architecture preservation (93.5% vs 19.6%) and higher diagnostic yield from cell blocks (97.8% vs 82.6%) than FNA[45]. Importantly, EUS-FNB enables acquisition of samples suitable for genomic analysis and next-generation sequencing[46].

EUS-FNB is increasingly favored over EUS-FNA given its higher diagnostic accuracy and similar safety, although most studies on biliary strictures evaluated EUS-FNA as the primary EUS-TA technique[32]. To further optimize tissue adequacy, macroscopic on-site evaluation (MOSE) and visual on-site evaluation (VOSE) can be applied during EUS-FNB. MOSE involves endosonographer inspection of the aspirated specimen for visible cores, whereas VOSE formalizes visual assessment using predefined criteria such as color and texture to predict adequacy[47-51]. Rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE), performed by a cytopathologist or pathology trainee, remains useful particularly for EUS-FNA[52], although its availability is limited in many centers. Training endosonographers to evaluate specimens themselves has been proposed as a solution.

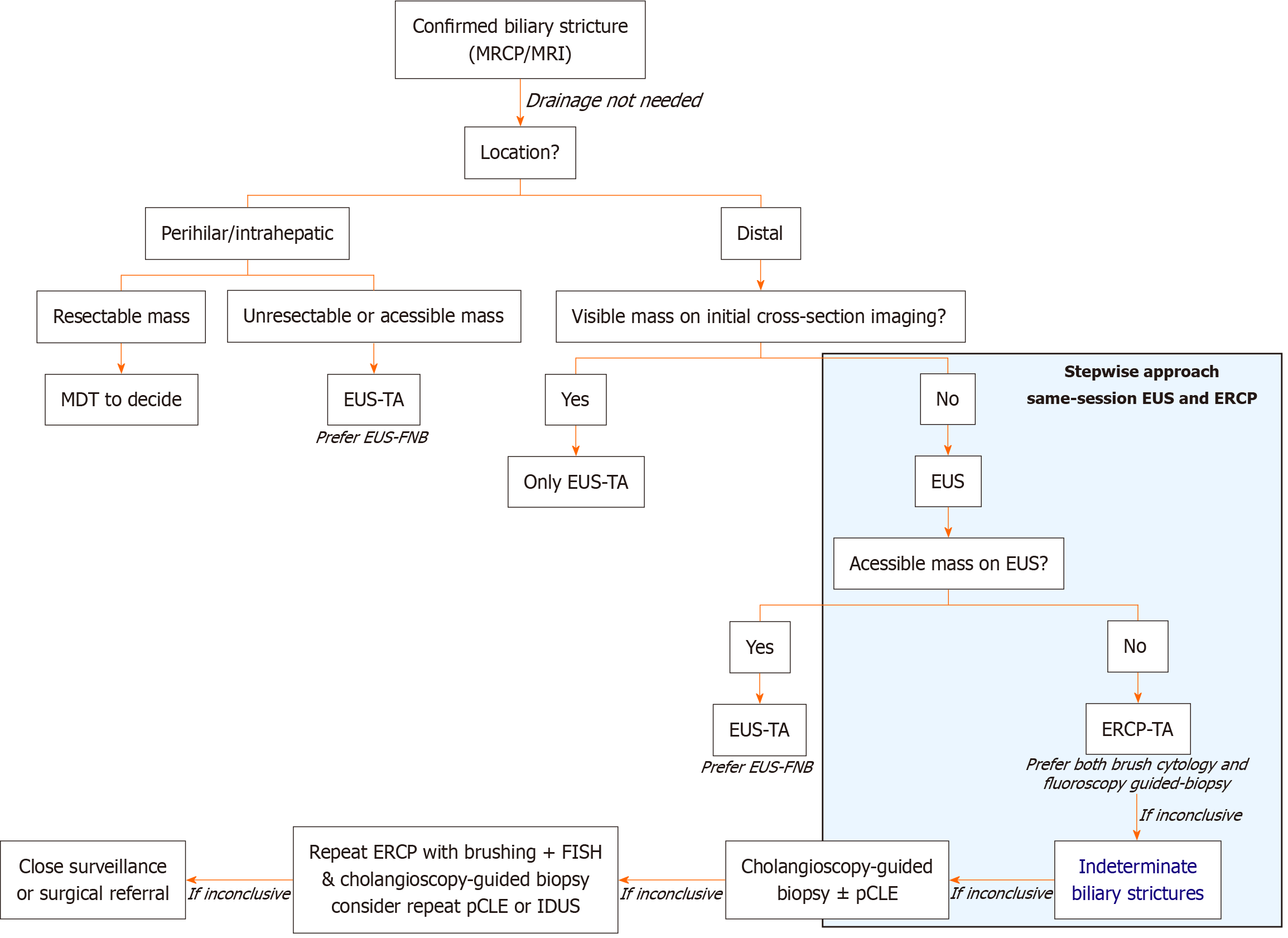

EUS is recommended by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) as the preferred initial diagnostic tool for extrahepatic/distal strictures, especially when malignancy is suspected, whether or not a mass is present in cross-sectional imaging. Subsequent guidance should rely on initial EUS findings. For perihilar or intrahepatic strictures, the strategy is often guided by prior imaging. If the disease is deemed unresectable or if an accessible mass is identified, EUS may be pursued first. If the lesion is potentially resectable, the approach becomes more nuanced and typically requires a multidisciplinary team discussion[21,52].

The most recent evidence supports the combined use of EUS and ERCP to achieve optimal diagnostic yield and guide management in a stepwise and integrated endoscopic management strategy for biliary strictures, especially when malignancy is suspected or when a distal stricture or mass is present[21,32]. Performing EUS and ERCP together significantly increases the sensitivity for detecting malignancy, reduces the need for repeat procedures, and facilitates faster diagnosis and treatment planning. This combined approach improves TA and diagnostic accuracy with a low rate of adverse events. The benefit is greater for patients with distal strictures. In such cases, even if a mass is not evident in cross-sectional imaging, the approach should begin with an EUS. If a mass is then present in ultrasound or if wall thickness is suitable for puncture, EUS-TA (ideally with FNB) should be performed. If a mass is absent or not approachable through EUS-TA, then ERCP-TA should be pursued. In comparison, for patients with a known distal mass on prior imaging, EUS-guided sampling may be sufficient, and ERCP might not be needed[21].

Several clinical trials and prospective studies further support the superiority of this combined approach over single-modality strategies. Studies show that performing EUS-TA and ERCP-TA in the same session improves diagnostic accuracy for MBSs. In a multicenter study of 263 patients, combined sampling achieved 85.8% sensitivity and 87.1% accuracy - higher than EUS-TA (73.6%/76.1%) or ERCP-TA (56.5%/60.5%) alone, particularly for pancreatic masses[53]. A single-center study of 51 patients reported similar findings, with 87.5% accuracy for the combined approach vs 80% for EUS-TA or 82.5% for ERCP-TA, without increased adverse events[54]. This strategy shortens the time to diagnosis, optimizes resource utilization, and does not increase complication rates compared with sequential or individual procedures, although procedure duration is longer[2,32,54,55]. According to the ESGE, the risk of complications may be higher for biliary lesions because the pancreatic duct is often patent rather than stenotic, which can increase the likelihood of post-procedural pancreatitis. Moreover, puncturing biliary lesions is technically more challenging than sampling pancreatic masses due to mobility, size, and surrounding vasculature. These factors seem to depend on lesion characteristics and may not be directly related to the sequence or combination of procedures[21]. Additionally, same-session EUS and ERCP usually require a lower total amount of anesthetic drugs than separate procedures, and anesthesia-related complications do not significantly differ between the two strategies[55-58]. Another advantage of performing both procedures consecutively is cost-effectiveness. In a retrospective single-center study, Gornals et al[59] reported an estimated savings of approximately €500 per patient for undergoing a single, combined procedure. Finally, combining both procedures in a single session improves overall patient satisfaction and may help reduce environmental impact compared to staging them separately, although this requires further investigation.

An integrated approach incorporating both techniques during the initial workup offers superior diagnostic performance, optimizes resource utilization, and streamlines patient management. It is important to emphasize that the success and safety of combining EUS and ERCP rely heavily on the skill and experience of the endoscopist, as well as the resources of the center. Although performing EUS and ERCP in a single session is recommended in high-volume centers with appropriate expertise and resources, several disadvantages limit its widespread adoption. Combined procedures require complex scheduling, reliable anesthesia support, and access to a fully equipped endoscopy suite, all of which may be difficult to secure in resource-limited hospitals. They also involve longer procedure times and greater anesthetic exposure, which may not be well tolerated by all patients. Furthermore, the limited availability of trained personnel and the need for additional pre-procedural evaluation in selected cases often necessitate separate sessions. These factors explain why, despite theoretical benefits, EUS and ERCP are still commonly performed separately in many institutions[2,21,32,60]. Hence, a stepwise approach for managing these patients should be carefully considered.

Classically, indeterminate biliary strictures (IDBSs) are defined as strictures without an associated known mass on imaging, in which initial tissue sampling during ERCP does not yield a definitive diagnosis[61]. IDBSs represent up to 20% of all biliary strictures following comprehensive evaluation with imaging, conventional ERCP-TA, and serum tumor markers[62]. The estimated risk of malignancy in IDBSs is approximately 60%, increasing to 80% when cytology is reported as “suspicious” and approximately 50% when described as “atypical”[63]. IDBSs are often associated with delayed diagnosis, allowing underlying malignancies to progress and negatively impacting patient outcomes.

IDBSs remain a diagnostic challenge requiring a systematic, multimodal, and stepwise approach tailored to local expertise and available resources. Both the ESGE and the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) recommend a diagnostic algorithm involving EUS-TA and ERCP-TA, considering advanced modalities such as cholangioscopy to play a crucial role. Guidelines specifically emphasize cholangioscopy for direct visualization and targeted biopsy when standard TA is inconclusive[21,32]. Cholangioscopy allows for the direct visualization of the biliary duct, enabling the endoscopist to biopsy strictures, playing a central role in the approach to IDBSs. However, its limited accuracy and higher rate of adverse events in distal strictures may limit its diagnostic potential in IDBSs located distally. Additionally, the diagnostic yield of cholangioscopy performed after prior ERCP-based biopsies or cytology decreases compared to cholangioscopy performed as the initial diagnostic modality. This reduction in yield is attributed to prior manipulation of the bile duct, including stent placement or TA, which may obscure or alter the stricture, making subsequent targeted biopsies less effective[32]. A recent multicenter study specifically found that both the sensitivity and overall accuracy of cholangioscopy-guided biopsies were significantly lower following stent placement or prior TA at ERCP. In this cohort, the sensitivity for malignancy or high-grade dysplasia dropped to 66.0% for single biopsies and 63.8% for bite-on-bite biopsies after prior manipulation, compared to higher yields reported in manipulation-naïve strictures. The number of biopsies did not compensate for this loss in sensitivity, and the effect was independent of the biopsy technique[35]. The ASGE acknowledges that prior ERCP interventions may impair the diagnostic performance of subsequent cholangioscopy but still recommends its use in centers with adequate expertise and equipment[32], particularly when a previous ERCP without cholangioscopy was nondiagnostic.

These limitations lead to a considerable number of biliary strictures - up to 40% - still remaining indeterminate[2]. Clinicians should reassess their diagnostic approach in specific scenarios[2,21,32], including: (1) Persistent nondiagnostic or inconclusive pathology despite extensive endoscopic sampling, particularly combined with a strong clinical suspicion of malignancy or discordance with imaging findings or the patient’s clinical course; (2) Conflicting results between diagnostic modalities (for example, benign cytology but a progressively worsening stricture or a suspicious mass on imaging); (3) Technical or sampling limitations, such as inability to reach the lesion, inadequate or non-representative specimens, or procedural difficulties; and (4) High-risk contexts, such as perihilar strictures in patients being evaluated for liver transplantation, where EUS-FNA of the primary lesion is generally avoided due to the potential risk of tumor seeding.

In such situations, repeat or alternative TA techniques, as well as referral to a specialized center with advanced diagnostic tools, should be considered. These tools include mostly ERCP-based techniques [probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy (pCLE), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), next-generation sequencing, and mutational profiling], EUS-based techniques [intraductal ultrasound (IDUS)] and when appropriate, surgical exploration[64-66]. pCLE provides real-time, high-resolution imaging of the biliary epithelium, with a reported sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 79% for malignancy, which is superior to ERCP-TA alone. However, its performance does not meet the threshold for oncologic decision-making at most centers and remains an adjunct at select referral centers[67,68]. FISH detects chromosomal abnormalities in biliary brushings, increasing sensitivity for malignancy. Adding FISH to cytology increases sensitivity from 20.1% to 42.9%, with high specificity (up to 99.3%) and a positive FISH (polysomy) conferring a high odds ratio for malignancy. FISH is particularly useful in cytology-negative cases[2,69]. IDUS uses a high-frequency ultrasound probe to provide cross-sectional imaging of the bile duct wall and surrounding tissue with an accuracy of up to 92% for malignancy, but it cannot provide tissue for histology and is less available in clinical practice[2,70]. Our proposed algorithm for guiding diagnosis is presented in Figure 1.

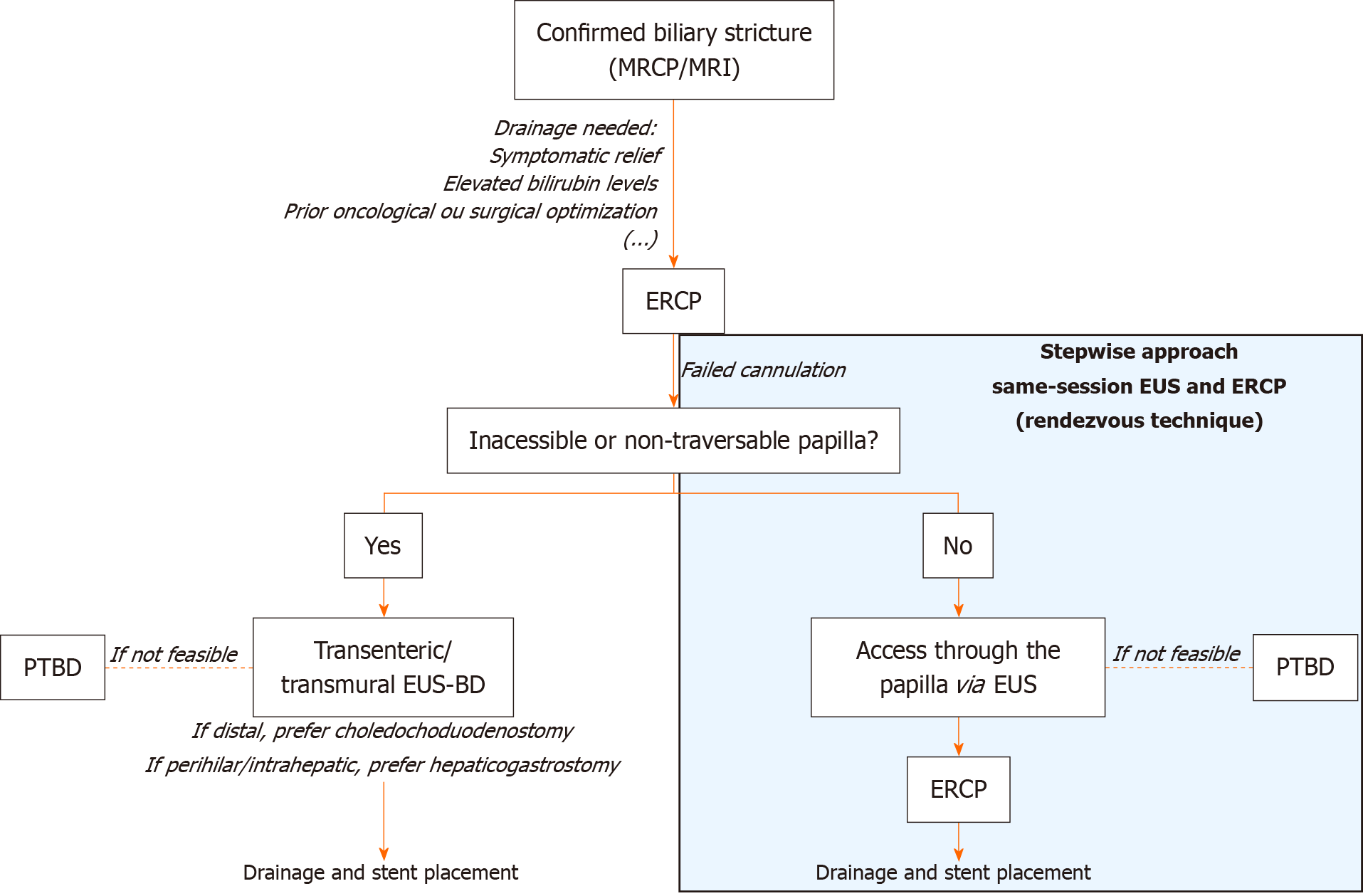

ERCP remains the first-line approach for the treatment of both BBSs and MBSs. However, it is estimated that ERCP is unsuccessful in relieving biliary obstruction in up to 5%-10% of cases[22], mostly due to altered anatomy which can make cannulation of the ampulla difficult or even impossible. In these situations, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) is considered a viable second option. Because it relieves biliary obstruction via an external biliary drain through a cutaneous incision, PTBD is associated with significant complications, including bacteremia, hemobilia, drain occlusion or dislodgement, and local skin infections[71-73]. Drainage may relieve symptoms, lower serum bilirubin levels, and optimize oncologic or surgical management in certain cases. Distal drainage is easier than in perihilar and intrahepatic locations due to anatomical and technical factors[2]. In MBSs, successful drainage is associated with reduced serum bilirubin and improved overall survival[74]. Quality of life improvements - appetite, energy, sleep, social function, and mental health - are also reported following effective drainage[75]. In BBSs, drainage leads to significant symptom relief and normalization of liver function tests[75,76]. Stent placement is central to the therapeutic strategy. In BBSs, the goal is long-term stricture resolution, which is typically achieved by sequential placement of multiple plastic stents or fully covered self-expandable metal stents (FCSEMSs). In MBSs, stenting is primarily used with palliative intentions or as a preoperative bridge to surgery when needed. When possible, FCSEMSs are increasingly used because they are easier to place, reduce the number of procedures, and are approved for a wide range of BBSs and MBSs[2,77,78].

Despite fewer therapeutic options compared to ERCP, EUS can be used for EUS-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD)[79]. EUS-BD allows stent placement either over a guidewire across the transmural tract between the gastrointestinal lumen and bile duct (transenteric/transmural stenting) or in an antegrade fashion through the papilla/stricture to facilitate ERCP cannulation[2]. The antegrade approach is preferred when the papilla is accessible, as it has slightly higher technical success. Transenteric/transmural EUS-BD is reserved for cases where transpapillary access is not possible, as in surgically altered anatomy, malignant duodenal obstruction, or tumor infiltration of the ampulla. Selection of EUS-BD techniques depends on patient anatomy and operator expertise[80,81]. EUS-BD is associated with a significantly lower risk of post-procedure pancreatitis, fewer reinterventions, and shorter hospital stays compared to ERCP, while stent migration and food impaction may be more frequent with EUS-BD[82-84]. Device selection has advanced considerably with the introduction of lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS), particularly electrocautery-enhanced LAMS. These allow single-step tract creation and stent deployment between the gastrointestinal lumen and bile duct, reducing procedure time and adverse events compared with multi-step techniques using plastic or conventional metal stents[42,85,86]. Available in different diameters, electrocautery-enhanced LAMS have improved technical and clinical success rates. Adjunctive accessories, such as guidewires, balloons for dilation, and double-pigtail plastic stents, may be used to optimize drainage or manage complications such as food impaction[87,88].

EUS-BD is non-inferior to ERCP for primary biliary drainage in malignant distal biliary obstruction and is recommended as an alternative to failed ERCP[89], surpassing PTBD due to its lower rates of complications. It should be considered an appropriate first-line option in expert centers[90]. Some contraindications to EUS-BD include inability to visualize the bile duct, tumor infiltration at the intended puncture site, massive ascites, uncorrectable coagulopathy, and standard contraindications to endoscopy and sedation[91]. In these particular cases, PTBD can be considered as a reasonable alternative.

The combined use of ERCP and EUS in the same session is primarily indicated for biliary strictures when standard ERCP cannulation fails or is not feasible[2,92]. EUS-guided access has emerged as a safe option to assist ERCP cannulation. This integrated and stepwise approach, called the rendezvous technique, involves puncturing the intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile duct with an FNA needle via EUS-guided access by passing a guidewire through the papilla in an antegrade manner to facilitate subsequent ERCP cannulation and stenting. Combining ERCP and EUS through the rendezvous technique is associated with several benefits. This technique increases ERCP technical success when ERCP alone is ineffective, with estimated technical success rates of approximately 90% and lower severe complication rates compared to other isolated transenteric EUS-guided drainage techniques[2,92-94]. It also avoids the use of PTBD, a procedure associated with higher rates of adverse events and complications[2]. Lastly, it is potentially associated with fewer reinterventions and complications compared to PTBD and possibly compared to ERCP alone in select scenarios[95]. Although the types of adverse events are similar between transenteric EUS-BD and the rendezvous technique, the latter is associated with a lower risk of severe complications[96,97]. Both approaches are recommended in high-volume centers with advanced endoscopic capability. Our proposed algorithm for guiding treatment is presented in Figure 2.

While advances in endoscopic techniques such as ERCP and EUS have significantly improved the management of biliary strictures, complementary technological innovations, particularly artificial intelligence (AI), are emerging as valuable tools to further enhance diagnosis, risk stratification, and procedural guidance. One promising application is AI-assisted ROSE during EUS-FNA. Some models have reported accuracies of 83%-89%, with sensitivity and specificity in the range of 78%-88% and 80%-88%, respectively, closely matching manual ROSE performance[98,99]. Similarly, AI models applied to EUS can improve cancer risk prediction, identifying subtle features of malignancy that may be overlooked by conventional assessment, while also aiding in the standardization and training of TA procedures[100,101]. In addition, deep learning and convolutional neural networks applied to cholangioscopy images have demonstrated robust capabilities in distinguishing benign from malignant strictures. Some models have achieved diagnostic accuracies exceeding 90% and areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.94. Studies show that these convolutional neural network-based AI models can outperform traditional visual assessment and surpass the sensitivity of ERCP-based tissue sampling. They may also enhance real-time decision-making and reduce sampling errors[102-105]. Despite promising results, clinical guidelines do not yet routinely recommend AI, as most models need validation and standardization before they can be widely applied. At present, AI serves as an adjunct rather than a replacement for established TA techniques.

Same-session EUS and ERCP optimize the diagnosis and treatment of biliary strictures, reducing repeat procedures and improving efficiency when performed in expert centers. For diagnosis, this combined strategy enhances TA and increases sensitivity for malignancy. For treatment, EUS-guided access with ERCP - particularly the rendezvous technique - improves biliary drainage and reduces complications compared with isolated approaches. Cholangioscopy should be reserved for selected cases, but future device improvements, especially in distal lesions, may broaden its role. The integration of validated AI models holds promise to further refine accuracy and streamline clinical management.

| 1. | Ni DJ, Yang QF, Nie L, Xu J, He SZ, Yao J. The past, present, and future of endoscopic management for biliary strictures: technological innovations and stent advancements. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1334154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Elmunzer BJ, Maranki JL, Gómez V, Tavakkoli A, Sauer BG, Limketkai BN, Brennan EA, Attridge EM, Brigham TJ, Wang AY. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Biliary Strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:405-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kapoor BS, Mauri G, Lorenz JM. Management of Biliary Strictures: State-of-the-Art Review. Radiology. 2018;289:590-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tummala P, Munigala S, Eloubeidi MA, Agarwal B. Patients with obstructive jaundice and biliary stricture ± mass lesion on imaging: prevalence of malignancy and potential role of EUS-FNA. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:532-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Coelen RJS, Roos E, Wiggers JK, Besselink MG, Buis CI, Busch ORC, Dejong CHC, van Delden OM, van Eijck CHJ, Fockens P, Gouma DJ, Koerkamp BG, de Haan MW, van Hooft JE, IJzermans JNM, Kater GM, Koornstra JJ, van Lienden KP, Moelker A, Damink SWMO, Poley JW, Porte RJ, de Ridder RJ, Verheij J, van Woerden V, Rauws EAJ, Dijkgraaf MGW, van Gulik TM. Endoscopic versus percutaneous biliary drainage in patients with resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:681-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zepeda-Gómez S, Baron TH. Benign biliary strictures: current endoscopic management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:573-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thomaidis T, Kallimanis G, May G, Zhou P, Sivanathan V, Mosko J, Triantafillidis JK, Teshima C, Moehler M. Advances in the endoscopic management of malignant biliary obstruction. Ann Gastroenterol. 2020;33:338-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Chandrasekhara V, Khashab MA, Muthusamy VR, Acosta RD, Agrawal D, Bruining DH, Eloubeidi MA, Fanelli RD, Faulx AL, Gurudu SR, Kothari S, Lightdale JR, Qumseya BJ, Shaukat A, Wang A, Wani SB, Yang J, DeWitt JM. Adverse events associated with ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:32-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 591] [Article Influence: 65.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mishra A, Tyberg A. Endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary drainage: a comprehensive review. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ang TL, Kwek ABE, Wang LM. Diagnostic Endoscopic Ultrasound: Technique, Current Status and Future Directions. Gut Liver. 2018;12:483-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chung HG, Chang JI, Lee KH, Park JK, Lee KT, Lee JK. Comparison of EUS and ERCP-guided tissue sampling in suspected biliary stricture. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0258887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Unal H, Gören İ, Eruzun H, Avcıoğlu U, Bektaş A. ERCP versus EUS-FNA For Tissue Diagnosis Of Biliary Strictures: A Seven Years Single Center Experience Results. Endoscopy. 2024;56:S324. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Boulay BR, Birg A. Malignant biliary obstruction: From palliation to treatment. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8:498-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fernandez Y Viesca M, Arvanitakis M. Early Diagnosis And Management Of Malignant Distal Biliary Obstruction: A Review On Current Recommendations And Guidelines. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2019;12:415-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Park W, Chawla A, O'Reilly EM. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 2021;326:851-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 798] [Cited by in RCA: 1306] [Article Influence: 261.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ballinger AB, McHugh M, Catnach SM, Alstead EM, Clark ML. Symptom relief and quality of life after stenting for malignant bile duct obstruction. Gut. 1994;35:467-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Maruyama A, Nishikawa T, Nagura A, Kurobe T, Yashika J, Nimura Y, Hu L, Yamaguchi T, Kojima I, Nonogaki K. Autopsy diagnosis of diffuse intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2025;18:154-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Oh DY, Ruth He A, Qin S, Chen LT, Okusaka T, Vogel A, Kim JW, Suksombooncharoen T, Ah Lee M, Kitano M, Burris H, Bouattour M, Tanasanvimon S, McNamara MG, Zaucha R, Avallone A, Tan B, Cundom J, Lee CK, Takahashi H, Ikeda M, Chen JS, Wang J, Makowsky M, Rokutanda N, He P, Kurland JF, Cohen G, Valle JW. Durvalumab plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022;1:EVIDoa2200015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 385] [Cited by in RCA: 694] [Article Influence: 173.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Valle JW, Kelley RK, Nervi B, Oh DY, Zhu AX. Biliary tract cancer. Lancet. 2021;397:428-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 728] [Article Influence: 145.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 20. | Singh A, Gelrud A, Agarwal B. Biliary strictures: diagnostic considerations and approach. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2015;3:22-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Facciorusso A, Crinò SF, Gkolfakis P, Spadaccini M, Arvanitakis M, Beyna T, Bronswijk M, Dhar J, Ellrichmann M, Gincul R, Hritz I, Kylänpää L, Martinez-Moreno B, Pezzullo M, Rimbaş M, Samanta J, van Wanrooij RLJ, Webster G, Triantafyllou K. Diagnostic work-up of bile duct strictures: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2025;57:166-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dumonceau JM, Tringali A, Papanikolaou IS, Blero D, Mangiavillano B, Schmidt A, Vanbiervliet G, Costamagna G, Devière J, García-Cano J, Gyökeres T, Hassan C, Prat F, Siersema PD, van Hooft JE. Endoscopic biliary stenting: indications, choice of stents, and results: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline - Updated October 2017. Endoscopy. 2018;50:910-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 529] [Cited by in RCA: 539] [Article Influence: 67.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | MacFadyen BV Jr, Vecchio R, Ricardo AE, Mathis CR. Bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The United States experience. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:315-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rymbai ML, Paul A, M J A, Anantrao AS, John R, Simon B, Joseph AJ, Raju RS, Sitaram V, Joseph P. Post cholecystectomy benign biliary stricture-isolated hepatic duct stricture: a proposed modification of the BISMUTH classification. ANZ J Surg. 2023;93:1306-1313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Katabathina VS, Dasyam AK, Dasyam N, Hosseinzadeh K. Adult bile duct strictures: role of MR imaging and MR cholangiopancreatography in characterization. Radiographics. 2014;34:565-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Petrick JL, Yang B, Altekruse SF, Van Dyke AL, Koshiol J, Graubard BI, McGlynn KA. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: A population-based study in SEER-Medicare. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Awali M, Stoleru G, Itani M, Buerlein R, Welle C, Anderson M, Chan A. Pancreatitis-related benign biliary strictures: a review of imaging findings and evolving endoscopic management. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2025;50:4589-4614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bowlus CL, Arrivé L, Bergquist A, Deneau M, Forman L, Ilyas SI, Lunsford KE, Martinez M, Sapisochin G, Shroff R, Tabibian JH, Assis DN. AASLD practice guidance on primary sclerosing cholangitis and cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2023;77:659-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Magnuson TH, Bender JS, Duncan MD, Ahrendt SA, Harmon JW, Regan F. Utility of magnetic resonance cholangiography in the evaluation of biliary obstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:63-71; discussion 71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Navaneethan U, Njei B, Lourdusamy V, Konjeti R, Vargo JJ, Parsi MA. Comparative effectiveness of biliary brush cytology and intraductal biopsy for detection of malignant biliary strictures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:168-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Ponchon T, Gagnon P, Berger F, Labadie M, Liaras A, Chavaillon A, Bory R. Value of endobiliary brush cytology and biopsies for the diagnosis of malignant bile duct stenosis: results of a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:565-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fujii-Lau LL, Thosani NC, Al-Haddad M, Acoba J, Wray CJ, Zvavanjanja R, Amateau SK, Buxbaum JL, Wani S, Calderwood AH, Chalhoub JM, Coelho-Prabhu N, Desai M, Elhanafi SE, Fishman DS, Forbes N, Jamil LH, Jue TL, Kohli DR, Kwon RS, Law JK, Lee JK, Machicado JD, Marya NB, Pawa S, Ruan W, Sawhney MS, Sheth SG, Storm A, Thiruvengadam NR, Qumseya BJ; (ASGE Standards of Practice Committee Chair [2020-2023]). American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on role of endoscopy in the diagnosis of malignancy in biliary strictures of undetermined etiology: methodology and review of evidence. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;98:694-712.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zhu L, Huang ZQ, Wang ZW, Yang XP, Hong JB, Yang ZZ, Yu ZP, Cao RL, He JL, Chen YX. A comparative study on the application of different endoscopic diagnostic methods in the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant bile duct strictures. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1143978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kushnir VM, Mullady DK, Das K, Lang G, Hollander TG, Murad FM, Jackson SA, Toney NA, Finkelstein SD, Edmundowicz SA. The Diagnostic Yield of Malignancy Comparing Cytology, FISH, and Molecular Analysis of Cell Free Cytology Brush Supernatant in Patients With Biliary Strictures Undergoing Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiography (ERC): A Prospective Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:686-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | de Jong DM, de Jonge PJF, Stassen PMC, Karagyozov P, Vila JJ, Fernández-Urién I, James MW, Venkatachalapathy SV, Oppong KW, Anderloni A, Repici A, Gabbiadini R, Joshi D, Ellrichmann M, Kylänpää L, Udd M, van der Heide F, Hindryckx P, Corbett G, Basiliya K, Cennamo V, Landi S, Phillpotts S, Webster GJ, Bruno MJ; European Cholangioscopy Group. The value of cholangioscopy-guided bite-on-bite (-on bite) biopsies in indeterminate biliary duct strictures. Endoscopy. 2025;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Gerges C, Beyna T, Tang RSY, Bahin F, Lau JYW, van Geenen E, Neuhaus H, Nageshwar Reddy D, Ramchandani M. Digital single-operator peroral cholangioscopy-guided biopsy sampling versus ERCP-guided brushing for indeterminate biliary strictures: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:1105-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Skenteris G, Singletary T, Grasso L, Self S, Schammel DP, Schammel CMG, Jones W, Devane AM. Effectiveness of cholangioscopy guided biopsy versus ERCP guided brushings in diagnosing malignant biliary strictures. Surg Endosc. 2025;39:1140-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Parsa N, Khashab MA. The Role of Peroral Cholangioscopy in Evaluating Indeterminate Biliary Strictures. Clin Endosc. 2019;52:556-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lübbe J, Arnelo U, Lundell L, Swahn F, Törnqvist B, Jonas E, Löhr JM, Enochsson L. ERCP-guided cholangioscopy using a single-use system: nationwide register-based study of its use in clinical practice. Endoscopy. 2015;47:802-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Sharzehi K, Sethi A, Savides T. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Subepithelial Lesions Encountered During Routine Endoscopy: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:2435-2443.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Facciorusso A, Sunny SP, Del Prete V, Antonino M, Muscatiello N. Comparison between fine-needle biopsy and fine-needle aspiration for EUS-guided sampling of subepithelial lesions: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:14-22.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mishra G, Lennon AM, Pausawasdi N, Shami VM, Sharaiha RZ, Elmunzer BJ. Quality Indicators for EUS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025;120:973-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Mohan BP, Madhu D, Reddy N, Chara BS, Khan SR, Garg G, Kassab LL, Muthusamy AK, Singh A, Chandan S, Facciorusso A, Mangiavillano B, Repici A, Adler DG. Diagnostic accuracy of EUS-guided fine-needle biopsy sampling by macroscopic on-site evaluation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;96:909-917.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Oppong KW, Bekkali NLH, Leeds JS, Johnson SJ, Nayar MK, Darné A, Egan M, Bassett P, Haugk B. Fork-tip needle biopsy versus fine-needle aspiration in endoscopic ultrasound-guided sampling of solid pancreatic masses: a randomized crossover study. Endoscopy. 2020;52:454-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Bang JY, Hebert-Magee S, Navaneethan U, Hasan MK, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. EUS-guided fine needle biopsy of pancreatic masses can yield true histology. Gut. 2018;67:2081-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Imaoka H, Sasaki M, Hashimoto Y, Watanabe K, Ikeda M. New Era of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Tissue Acquisition: Next-Generation Sequencing by Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Sampling for Pancreatic Cancer. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Chong CCN, Lakhtakia S, Nguyen N, Hara K, Chan WK, Puri R, Almadi MA, Ang TL, Kwek A, Yasuda I, Doi S, Kida M, Wang HP, Cheng TY, Jiang Q, Yang A, Chan AWH, Chan S, Tang R, Iwashita T, Teoh AYB. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition with or without macroscopic on-site evaluation: randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2020;52:856-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Giri S, Uppin MS, Kumar L, Uppin S, Pamu PK, Angadi S, Bhrugumalla S. Impact of macroscopic on-site evaluation on the diagnostic outcomes of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2023;51:569-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Iwashita T, Yasuda I, Mukai T, Doi S, Nakashima M, Uemura S, Mabuchi M, Shimizu M, Hatano Y, Hara A, Moriwaki H. Macroscopic on-site quality evaluation of biopsy specimens to improve the diagnostic accuracy during EUS-guided FNA using a 19-gauge needle for solid lesions: a single-center prospective pilot study (MOSE study). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:177-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | So H, Seo DW, Hwang JS, Ko SW, Oh D, Song TJ, Park DH, Lee SK, Kim MH. Macroscopic on-site evaluation after EUS-guided fine needle biopsy may replace rapid on-site evaluation. Endosc Ultrasound. 2021;10:111-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Stigliano S, Balassone V, Biasutto D, Covotta F, Signoretti M, Di Matteo FM. Accuracy of visual on-site evaluation (Vose) In predicting the adequacy of Eus-guided fine needle biopsy: A single center prospective study. Pancreatology. 2021;21:312-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Facciorusso A, Arvanitakis M, Crinò SF, Fabbri C, Fornelli A, Leeds J, Archibugi L, Carrara S, Dhar J, Gkolfakis P, Haugk B, Iglesias Garcia J, Napoleon B, Papanikolaou IS, Seicean A, Stassen PMC, Vilmann P, Tham TC, Fuccio L. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue sampling: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical and Technology Review. Endoscopy. 2025;57:390-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 53. | Jo JH, Cho CM, Jun JH, Chung MJ, Kim TH, Seo DW, Kim J, Park DH; Research Group for Endoscopic Ultrasonography in KSGE. Same-session endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-based tissue sampling in suspected malignant biliary obstruction: A multicenter experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:799-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Troncone E, Gadaleta F, Paoluzi OA, Gesuale CM, Formica V, Morelli C, Roselli M, Savino L, Palmieri G, Monteleone G, Del Vecchio Blanco G. Endoscopic Ultrasound Plus Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Based Tissue Sampling for Diagnosis of Proximal and Distal Biliary Stenosis Due to Cholangiocarcinoma: Results from a Retrospective Single-Center Study. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:1730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Purnak T, El Hajj II, Sherman S, Fogel EL, McHenry L, Lehman G, Gromski MA, Al-Haddad M, DeWitt J, Watkins JL, Easler JJ. Combined Versus Separate Sessions of Endoscopic Ultrasound and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography for the Diagnosis and Management of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma with Biliary Obstruction. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:2786-2794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Vila JJ, Kutz M, Goñi S, Ostiz M, Amorena E, Prieto C, Rodriguez C, Fernández-Urien I, Jiménez FJ. Endoscopic and anesthetic feasibility of EUS and ERCP combined in a single session versus two different sessions. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:57-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Aslanian HR, Estrada JD, Rossi F, Dziura J, Jamidar PA, Siddiqui UD. Endoscopic ultrasound and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for obstructing pancreas head masses: combined or separate procedures? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:711-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Gorris M, van der Valk NP, Fockens P, Jacobs MA, Montazeri NSM, Voermans RP, Wielenga MC, van Hooft JE, van Wanrooij RL. Does same session EUS-guided tissue acquisition and ERCP increase the risk of pancreatitis in patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction? HPB (Oxford). 2022;24:1634-1641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Gornals JB, Moreno R, Castellote J, Loras C, Barranco R, Catala I, Xiol X, Fabregat J, Corbella X. Single-session endosonography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for biliopancreatic diseases is feasible, effective and cost beneficial. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:578-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Tang RSY. Endoscopic evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures: Cholangioscopy, endoscopic ultrasound, or both? Dig Endosc. 2024;36:778-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Angsuwatcharakon P, Kulpatcharapong S, Moon JH, Ramchandani M, Lau J, Isayama H, Seo DW, Maydeo A, Wang HP, Nakai Y, Ratanachu-Ek T, Bapaye A, Hu B, Devereaux B, Ponnudurai R, Khor C, Kongkam P, Pausawasdi N, Ridtitid W, Piyachaturawat P, Khanh PC, Dy F, Rerknimitr R. Consensus guidelines on the role of cholangioscopy to diagnose indeterminate biliary stricture. HPB (Oxford). 2022;24:17-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Bowlus CL, Olson KA, Gershwin ME. Evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:28-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Lieb KR, Williams ZE, Sayles H, Zaman M, Dhir M. Risk of Malignancy for Indeterminate Cytology of Bile Duct Strictures: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2025;32:5657-5666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Lin TY, Chen CC, Kuo YT, Liao WC. Endoscopic and novel approaches for evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures. J Formos Med Assoc. 2025;S0929-6646(25)00266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Arechederra M, Rullán M, Amat I, Oyon D, Zabalza L, Elizalde M, Latasa MU, Mercado MR, Ruiz-Clavijo D, Saldaña C, Fernández-Urién I, Carrascosa J, Jusué V, Guerrero-Setas D, Zazpe C, González-Borja I, Sangro B, Herranz JM, Purroy A, Gil I, Nelson LJ, Vila JJ, Krawczyk M, Zieniewicz K, Patkowski W, Milkiewicz P, Cubero FJ, Alkorta-Aranburu G, G Fernandez-Barrena M, Urman JM, Berasain C, Avila MA. Next-generation sequencing of bile cell-free DNA for the early detection of patients with malignant biliary strictures. Gut. 2022;71:1141-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Gonda TA, Viterbo D, Gausman V, Kipp C, Sethi A, Poneros JM, Gress F, Park T, Khan A, Jackson SA, Blauvelt M, Toney N, Finkelstein SD. Mutation Profile and Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization Analyses Increase Detection of Malignancies in Biliary Strictures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:913-919.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Slivka A, Gan I, Jamidar P, Costamagna G, Cesaro P, Giovannini M, Caillol F, Kahaleh M. Validation of the diagnostic accuracy of probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy for the characterization of indeterminate biliary strictures: results of a prospective multicenter international study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:282-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Mi J, Han X, Wang R, Ma R, Zhao D. Diagnostic accuracy of probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy and tissue sampling by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in indeterminate biliary strictures: a metaanalysis. Sci Rep. 2022;12:7257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Brooks C, Gausman V, Kokoy-Mondragon C, Munot K, Amin SP, Desai A, Kipp C, Poneros J, Sethi A, Gress FG, Kahaleh M, Murty VV, Sharaiha R, Gonda TA. Role of Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization, Cholangioscopic Biopsies, and EUS-FNA in the Evaluation of Biliary Strictures. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:636-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Yadlapati S, Mulki R, Sánchez-Luna SA, Ahmed AM, Kyanam Kabir Baig KR, Peter S. Clinical approach to indeterminate biliary strictures: Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and workup. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:5198-5210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 71. | Molina H, Chan MM, Lewandowski RJ, Gabr A, Riaz A. Complications of Percutaneous Biliary Procedures. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2021;38:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Ginat D, Saad WE, Davies MG, Saad NE, Waldman DL, Kitanosono T. Incidence of cholangitis and sepsis associated with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drain cholangiography and exchange: a comparison between liver transplant and native liver patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W73-W77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Oh HC, Lee SK, Lee TY, Kwon S, Lee SS, Seo DW, Kim MH. Analysis of percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy-related complications and the risk factors for those complications. Endoscopy. 2007;39:731-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Tavakkoli A, Elmunzer BJ, Waljee AK, Murphy CC, Pruitt SL, Zhu H, Rong R, Kwon RS, Scheiman JM, Rubenstein JH, Singal AG. Survival analysis among unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients undergoing endoscopic or percutaneous interventions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93:154-162.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Abraham NS, Barkun JS, Barkun AN. Palliation of malignant biliary obstruction: a prospective trial examining impact on quality of life. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:835-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Janssen JJ, van Delden OM, van Lienden KP, Rauws EA, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ, Laméris JS. Percutaneous balloon dilatation and long-term drainage as treatment of anastomotic and nonanastomotic benign biliary strictures. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37:1559-1567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Strand DS, Law RJ, Yang D, Elmunzer BJ. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Endoscopic Approach to Recurrent Acute and Chronic Pancreatitis: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:1107-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Sato T, Kogure H, Nakai Y, Ishigaki K, Hakuta R, Saito K, Saito T, Takahara N, Hamada T, Mizuno S, Tada M, Isayama H, Koike K. A prospective study of fully covered metal stents for different types of refractory benign biliary strictures. Endoscopy. 2020;52:368-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Sato T, Nakai Y, Fujishiro M. Current endoscopic approaches to biliary strictures. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2022;38:450-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Boulay BR, Lo SK. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2018;28:171-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Tyberg A, Desai AP, Kumta NA, Brown E, Gaidhane M, Sharaiha RZ, Kahaleh M. EUS-guided biliary drainage after failed ERCP: a novel algorithm individualized based on patient anatomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:941-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Park JK, Woo YS, Noh DH, Yang JI, Bae SY, Yun HS, Lee JK, Lee KT, Lee KH. Efficacy of EUS-guided and ERCP-guided biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction: prospective randomized controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88:277-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Lyu Y, Li T, Cheng Y, Wang B, Cao Y, Wang Y. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided vs ERCP-guided biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction: A up-to-date meta-analysis and systematic review. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:1247-1253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 84. | Gopakumar H, Singh RR, Revanur V, Kandula R, Puli SR. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided vs Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography-Guided Biliary Drainage as Primary Approach to Malignant Distal Biliary Obstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:1607-1615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Paduano D, Facciorusso A, De Marco A, Ofosu A, Auriemma F, Calabrese F, Tarantino I, Franchellucci G, Lisotti A, Fusaroli P, Repici A, Mangiavillano B. Endoscopic Ultrasound Guided Biliary Drainage in Malignant Distal Biliary Obstruction. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Anderloni A, Troncone E, Fugazza A, Cappello A, Del Vecchio Blanco G, Monteleone G, Repici A. Lumen-apposing metal stents for malignant biliary obstruction: Is this the ultimate horizon of our experience? World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:3857-3869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 87. | Ginestet C, Sanglier F, Hummel V, Rouchaud A, Legros R, Lepetit H, Dahan M, Carrier P, Loustaud-Ratti V, Sautereau D, Albouys J, Jacques J, Geyl S. EUS-guided biliary drainage with electrocautery-enhanced lumen-apposing metal stent placement should replace PTBD after ERCP failure in patients with distal tumoral biliary obstruction: a large real-life study. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:3365-3373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Ramai D, Dawod E, Darwin PE, Kim RE, Kim JH, Wang J, Lanka C, Bakain T, Mahadev S, Sampath K, Carr-Locke DL, Morris JD, Sharaiha RZ. Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Transmural Biliary Drainage With 6 mm and 8 mm Cautery-enhanced Lumen-apposing Metal Stents: A Multicenter Collaborative Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2025;59:376-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Wang K, Zhu J, Xing L, Wang Y, Jin Z, Li Z. Assessment of efficacy and safety of EUS-guided biliary drainage: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1218-1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Barbosa EC, Santo PADE, Baraldo S, Nau AL, Meine GC. EUS- versus ERCP-guided biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2024;100:395-405.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Forbes N, Coelho-Prabhu N, Al-Haddad MA, Kwon RS, Amateau SK, Buxbaum JL, Calderwood AH, Elhanafi SE, Fujii-Lau LL, Kohli DR, Pawa S, Storm AC, Thosani NC, Qumseya BJ. Adverse events associated with EUS and EUS-guided procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:16-26.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Dell'Anna G, Ogura T, Vanella G, Nishikawa H, Lakhtakia S, Arcidiacono PG. Endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary interventions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;60-61:101810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Mallery S, Matlock J, Freeman ML. EUS-guided rendezvous drainage of obstructed biliary and pancreatic ducts: Report of 6 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:100-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Klair JS, Zafar Y, Ashat M, Bomman S, Murali AR, Jayaraj M, Law J, Larsen M, Singh DP, Rustagi T, Irani S, Ross A, Kozarek R, Krishnamoorthi R. Effectiveness and Safety of EUS Rendezvous After Failed Biliary Cannulation With ERCP: A Systematic Review and Proportion Meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57:211-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice Committee; Marya NB, Pawa S, Thiruvengadam NR, Ngamruengphong S, Baron TH, Bun Teoh AY, Bent CK, Abidi W, Alipour O, Amateau SK, Desai M, Chalhoub JM, Coelho-Prabhu N, Cosgrove N, Elhanafi SE, Forbes N, Fujii-Lau LL, Kohli DR, Machicado JD, Navaneethan U, Ruan W, Sheth SG, Thosani NC, Qumseya BJ; (ASGE Standards of Practice Committee Chair). American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on the role of therapeutic EUS in the management of biliary tract disorders: methodology and review of evidence. Gastrointest Endosc. 2024;100:e79-e135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Khan MA, Akbar A, Baron TH, Khan S, Kocak M, Alastal Y, Hammad T, Lee WM, Sofi A, Artifon EL, Nawras A, Ismail MK. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:684-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Khashab MA, Valeshabad AK, Modayil R, Widmer J, Saxena P, Idrees M, Iqbal S, Kalloo AN, Stavropoulos SN. EUS-guided biliary drainage by using a standardized approach for malignant biliary obstruction: rendezvous versus direct transluminal techniques (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:734-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Fujii Y, Uchida D, Sato R, Obata T, Akihiro M, Miyamoto K, Morimoto K, Terasawa H, Yamazaki T, Matsumoto K, Horiguchi S, Tsutsumi K, Kato H, Inoue H, Cho T, Tanimoto T, Ohto A, Kawahara Y, Otsuka M. Effectiveness of data-augmentation on deep learning in evaluating rapid on-site cytopathology at endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Sci Rep. 2024;14:22441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Lin R, Sheng LP, Han CQ, Guo XW, Wei RG, Ling X, Ding Z. Application of artificial intelligence to digital-rapid on-site cytopathology evaluation during endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration: A proof-of-concept study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;38:883-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Khalaf K, Terrin M, Jovani M, Rizkala T, Spadaccini M, Pawlak KM, Colombo M, Andreozzi M, Fugazza A, Facciorusso A, Grizzi F, Hassan C, Repici A, Carrara S. A Comprehensive Guide to Artificial Intelligence in Endoscopic Ultrasound. J Clin Med. 2023;12:3757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 101. | Wu Y, Ramai D, Smith ER, Mega PF, Qatomah A, Spadaccini M, Maida M, Papaefthymiou A. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Ultrasound: Current Developments, Limitations and Future Directions. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16:4196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Marya NB, Powers PD, Petersen BT, Law R, Storm A, Abusaleh RR, Rau P, Stead C, Levy MJ, Martin J, Vargas EJ, Abu Dayyeh BK, Chandrasekhara V. Identification of patients with malignant biliary strictures using a cholangioscopy-based deep learning artificial intelligence (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:268-278.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 103. | Robles-Medranda C, Verpalen I, Schulz D, Spadaccini M. Artificial Intelligence in Biliopancreatic Disorders: Applications in Cross-Sectional Imaging and Endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2025;169:471-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Saraiva MM, Ribeiro T, Ferreira JPS, Boas FV, Afonso J, Santos AL, Parente MPL, Jorge RN, Pereira P, Macedo G. Artificial intelligence for automatic diagnosis of biliary stricture malignancy status in single-operator cholangioscopy: a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:339-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Mascarenhas M, Almeida MJ, González-Haba M, Castillo BA, Widmer J, Costa A, Fazel Y, Ribeiro T, Mendes F, Martins M, Afonso J, Cardoso P, Mota J, Fernandes J, Ferreira J, Boas FV, Pereira P, Macedo G. Artificial intelligence for automatic diagnosis and pleomorphic morphological characterization of malignant biliary strictures using digital cholangioscopy. Sci Rep. 2025;15:5447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/