INTRODUCTION

The gut contains the largest independent immune system in the body, and this system is tasked with ensuring an appropriate response to the foreign antigens to which it is constantly exposed[1]. The gut produces a strong protective immune response against pathogenic antigens, but a similar response to harmless dietary proteins or symbiotic microorganisms can lead to chronic inflammatory diseases[2]. The mononuclear macrophage system, which is composed of macrophages (Mφs) and dendritic cells (DCs), is at the heart of the immune response and therefore holds promise as a potential target for new therapies to treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[3].

The enteric nervous system (ENS) is a complete neural network that exists in the gastrointestinal epithelium and is independent of the brain. Physiologically, this system plays a role in sensing, initiating and regulating gastrointestinal motility and secretion[4]. Various clinical gastrointestinal motility disorders involve the intestinal nervous system. The ENS was recently defined as a branch of the parasympathetic nervous system and is a popular research topic in the fields of gastrointestinal physiology and neurobiology[5]. This review discusses the relationship between macrophages and intestinal neurons and suggests new ways of investigating the cholinergic anti-inflammatory mechanism and new ideas for the use of electrophysiological stimulation of the vagus nerve (VN) (vagus nerve stimulation, VNS) to treat IBD.

MACROPHAGES PLAY A KEY ROLE IN RESTORING THE INTESTINAL BALANCE

Macrophages that reside in the intestinal epithelium have important physiological functions, such as the clearance of apoptotic or senescent cells and tissue remodeling[6]. In addition, intestinal macrophages produce various cytokines and other soluble factors that help maintain intestinal homeostasis. Prostaglandin E2, which enables local macrophages to stimulate the proliferation of epithelial progenitor cells in intestinal crypts, thereby regulating the integrity of the epithelial barrier, is one of these factors. macrophages located in the muscular and serosal layers play important roles in interactions with the nervous system to promote peristalsis and ensure the continuous movement of ingested substances through the gut[7]. In a dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis model, sensitivity to DSS was increased by knocking out CSF1R in macrophages; notably, epithelial cell repair in this model requires myeloid differentiation factor 88 signaling, reflecting the importance of macrophages in maintaining intestinal homeostasis[8].

Macrophages are derived mainly from bone marrow precursor cells, the differentiation of which is regulated by various cytokines and which eventually mature into macrophages. The polarization of bone marrow-derived macrophages to different phenotypes, mainly the M1 and M2 phenotypes, can be induced by various stimuli[9]. Polarized macrophages aggregate locally in the intestinal segment affected by IBD lesions and exert their biological effects by releasing various proinflammatory factors (M1 macrophages) or regulatory anti-inflammatory cytokines (M2 macrophages). After stimulation and activation, M1 macrophages secrete many proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-12, IL-23, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). Moreover, nitric oxide (NO) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by L-arginine are degraded by induced NO synthase, which is highly expressed[10]. These agents participate in phagocytosing bacteria and chemotactic inflammatory cells, promoting Th1 and Th17 cell-mediated immune responses and other processes and exerting host immune functions, leading to inflammatory damage in the intestinal tissue of IBD patients. M2 macrophages can secrete immunosuppressive factors such as IL-10 and chemokines (CCL17, CCL22, and CCL24) in response to IL-4, IL-13 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) stimulation[11]. In addition to activating the Th2 immune response, these macrophages inhibit the Th1 immune response, exert anti-inflammatory effects, and promote wound repair and fibrosis. In addition, macrophages participate in immune regulation, regulating the intestinal immune response by inducing the expression of multiple cytokines and cell surface receptors[12].

Currently, the etiology of IBD is unknown; however, its pathogenesis involves various immune, genetic and environmental factors. Alterations in the gut microbiota play important roles in immune regulation in patients with IBD. Many studies have shown that intestinal microbial disorders are related to acute and chronic infections[13]. Metagenomic studies have shown decreased diversity and stability of the gut microbiota in IBD patients compared with healthy individuals. In addition, immune cells in the gastrointestinal tract, especially macrophages, respond to bacteria and bacterial antigens to varying degrees[14]. Intestinal macrophages are innate immune cells that play important roles in host defense. In the gut, macrophages in different regions play different functional roles and have different morphological characteristics[15].

Most of the macrophages located in the lamina propria (Lp) of the human colon mucosa are concentrated in the subepithelial region and are large and round[16]. However, the macrophages in the deep mucosa propria are small and irregular in shape[17]. Similarly, the macrophages in the Lp mucosa of the small intestine are smaller than those in the colon and elliptical or irregular in shape. For example, macrophages in the Lp express the receptor CX3CR1, which may play a role in controlling the differentiation and function of intestinal macrophages. CX3CR1 deficiency has been reported to reduce the number of intestinal macrophages and alter their susceptibility to chemically induced colitis. In addition, the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokine receptors, such as IL-10, allows Lp macrophages to prevent imbalances in the intestinal microbiota and develop tolerance to dietary antigens[18]. In contrast to Lp macrophages, macrophages located in the serosal layer are close to the dense and complex myoneural plexus, which, together with the submucosal plexus, innervates the intestinal nervous system or ENS[19]. However, macrophages in the serosal layer have a greater volume than those in the LP, and notably, the different Mφ subtypes that contact intestinal neurons differ not only in location and function but also in heterogeneity. Lp macrophages exhibit proinflammatory characteristics, including high expression levels of Il1b and Il2b. M macrophages can tolerate stress and express the Arg1, Chi3 L3 and Cd163 genes[20].

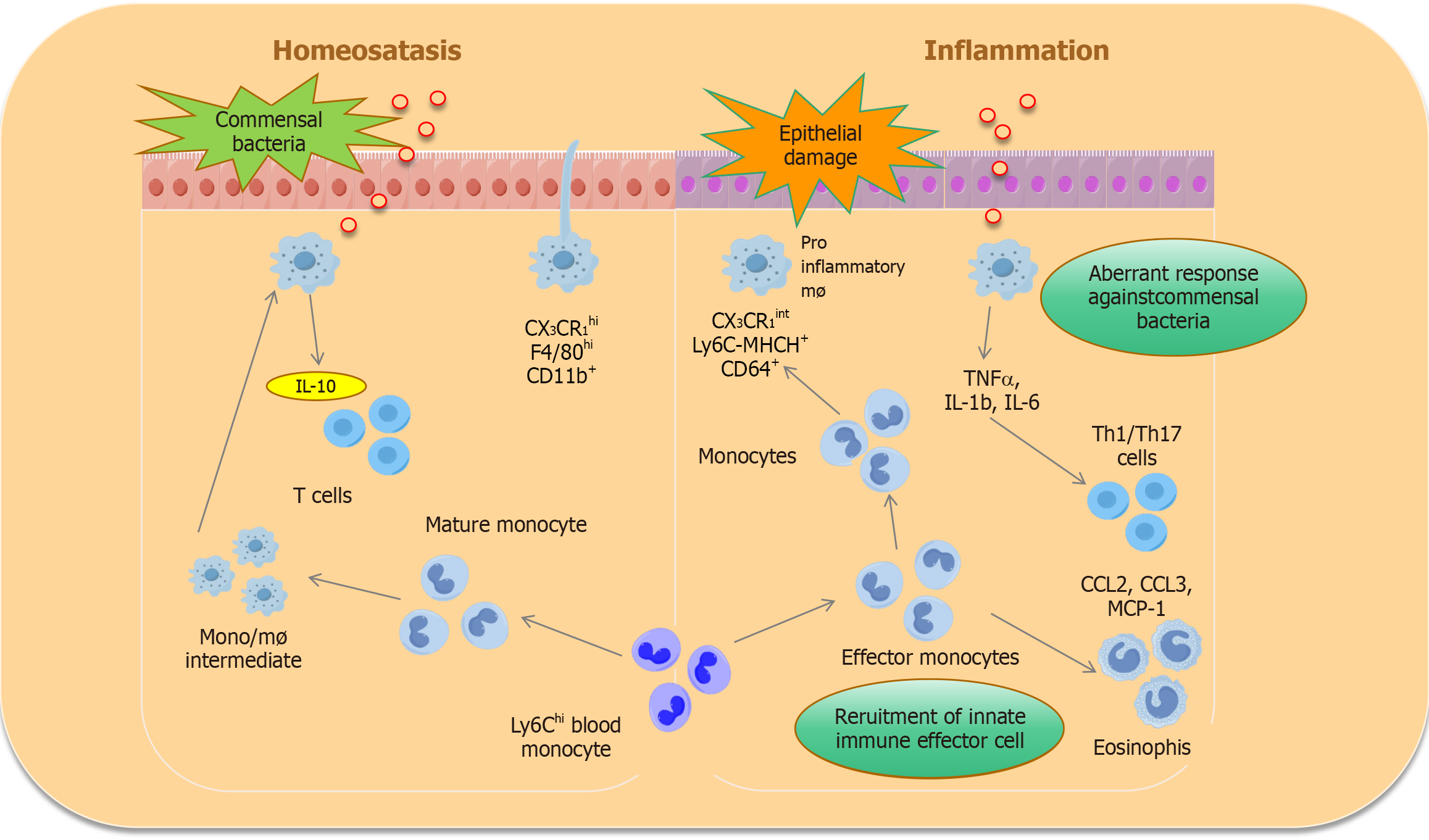

Intestinal macrophages play a key role in maintaining intestinal balance. Under the stimulation of immunopathogenic factors, to maintain intestinal homeostasis, resident macrophages can selectively express protective regulatory factors such as IL-10 and TGF-β[21]. The STAT6-dependent M2 polarization of macrophages has been shown to increase the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 through activation of the Wnt signaling pathway, thereby promoting mucosal repair in mice treated with 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid solution (TNBS)[22]. Another study revealed that IL-10 knockout mice develop spontaneous enteritis and that the absence of the IL-10 receptor or its key downstream transcription factor STAT3 in macrophages also leads to increased susceptibility to enteritis[23]. Furthermore, IL-10 was shown to inhibit the transcription and synthesis of the IL-1β precursor in macrophages and the activation of caspase-1. Specifically, blocking IL-10R in macrophages leads to excessive production of IL-1β, induced a Th17-type immune response, and further exacerbates intestinal inflammation. Moreover, IL-10 effectively decreases the secretion and expression of the proinflammatory factors IL-1 and IL-6 in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated macrophages[24]. IL-10 can also inhibit the activation of monocytes/macrophages and the expression of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II antigen and reduce the production of IL-2 and IFN-γ. Furthermore, IL-10 directly antagonizes the proliferation and cytotoxic response of Th1 cells, reduces the production of IFN-γ and TNF-α, prevents the occurrence of inflammatory reactions, restores the tolerance of the intestinal microbiota, and alleviates intestinal symptoms[25]. Recent research has shown that IL-10 inhibits Mφ activity by inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway, inhibits glucose uptake and glycolysis after LPS stimulation, and promotes oxidative phosphorylation, thus maintaining intestinal homeostasis[26] (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Macrophage differentiation under steady-state and disease conditions.

IL: Interleukin; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor α.

In addition, the mechanism through which the intestinal mucosa enables the continuous recruitment and differentiation of Ly6Chi monocytes is not fully understood. One of the mechanisms may involve continuous exposure to symbiotic microorganisms and other environmental factors found on the barrier surface. A recent study revealed that the αvβ5 integrin protein is upregulated during intestinal macrophage development and that the number of intestinal monocytes is reduced in mice lacking αvβ5 integrin, suggesting that the regulation of αvβ5 integrin plays an important role in the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages and the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis[27].

In summary, these findings provide an important basis for studying the use of mononuclear macrophages to treat colitis. Specifically, these observations demonstrate that mononuclear macrophages can effectively reduce the incidence of colitis by inhibiting the inflammatory response.

THE ENS

The ENS consists of many neurons buried in the gastrointestinal wall. These cells vary in size and structure, forming many gastrointestinal ganglia, also known as nerve plexuses, namely, intermuscular nerve plexuses and submucosal nerve plexuses. These ganglia are distinct from peripheral nervous system ganglia. Notably, there are no blood vessels or connective tissue between the neurons of the ENS; rather, part of the membrane surface of a neuron establishes direct contact with the intercellular space to absorb nutrients[28]. The protuberances of glial cells in the ganglion enclose nerve components and form the outer basement membrane, confining capillaries outside the basement membrane. Moreover, the endothelial cells of these capillaries that provide nutrients to the ganglia are continuous and have no fenestrations, forming a "blood-intestinal plexus barrier" similar to the blood-brain barrier.

On the basis of the different transmitters released and their functions, enteric nerves can be divided into three categories, one of which is cholinergic excitatory nerves. The cell bodies of cholinergic excitatory nerves are scattered in submucosal and intermuscular nerve clusters, and their nerve endings supply and innervate the gastrointestinal longitudinalis and circumferential muscles or form synaptic connections with other neurons in the nerve plexus. The release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) activates the M-choline receptor on smooth muscle or the N-choline receptor on ganglion cells, causing gastrointestinal muscle excitation and thereby participating in the intestinal peristaltic reflex. Gastrointestinal motor function (e.g., segmental movement of the small intestine and peristalsis) is regulated mainly by the local ENS and is relatively independent of the central nervous system[29]. For example, the peristaltic reflex of the intestine can be demonstrated in vitro. Cutting the vagus or sympathetic nerve also has little effect on gastrointestinal tract movement. Abnormal ENS function or loss of ENS function leads to gastrointestinal dysfunction. Intestinal infarction is caused by the continuous excitation of endogenous inhibitory nerves innervating the annulus muscle. Conversely, enterospasm and achalasia are caused by poor endogenous inhibitory nerve function. Hirschsprung’s disease is caused by the congenital absence of intramural ganglion cells in the distal section of the colon, rectum or anal canal; in this disease, these sections of the intestine cannot achieve normal intestinal peristalsis, causing the intestinal cavity above the region to expand, and in severe cases, the entire colon is involved[30].

THE CHOLINERGIC ANTI-INFLAMMATORY PATHWAY

The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (CAIP) refers mainly to the pathway through which pathogenic bacteria invade the human body. In this pathway, receptors sense changes in the environment, causing an increase in the generation of nerve impulses, which are subsequently transmitted to the nerve center. After the integration and analysis of an impulse signal by the central nervous system, the VN is activated. The anti-inflammatory transmitter ACh is released from peripheral VN endings, and then ACh binds to the α7 nicotinic ACh receptor (α7nAChR) on immune cells, inhibits the production and release of proinflammatory factors through intracellular signal transduction, and ultimately inhibits the local or systemic inflammatory response[31]. The CAIP is mediated by VN efferent fibers in contact with intestinal neurons. These efferent fibers release ACh at the synaptic junctions of macrophages, and ACh binds to α7nAChR and inhibits the production of proinflammatory cytokines[32]. Anti-inflammatory signals reach the reticuloendothelial system of the spleen, liver and gastrointestinal tract via efferent fibers of the VN. ACh released by the VN subsequently interacts with α7nAchR expressed by macrophages and other cytokine-secreting cells to inhibit cytokine synthesis[33].

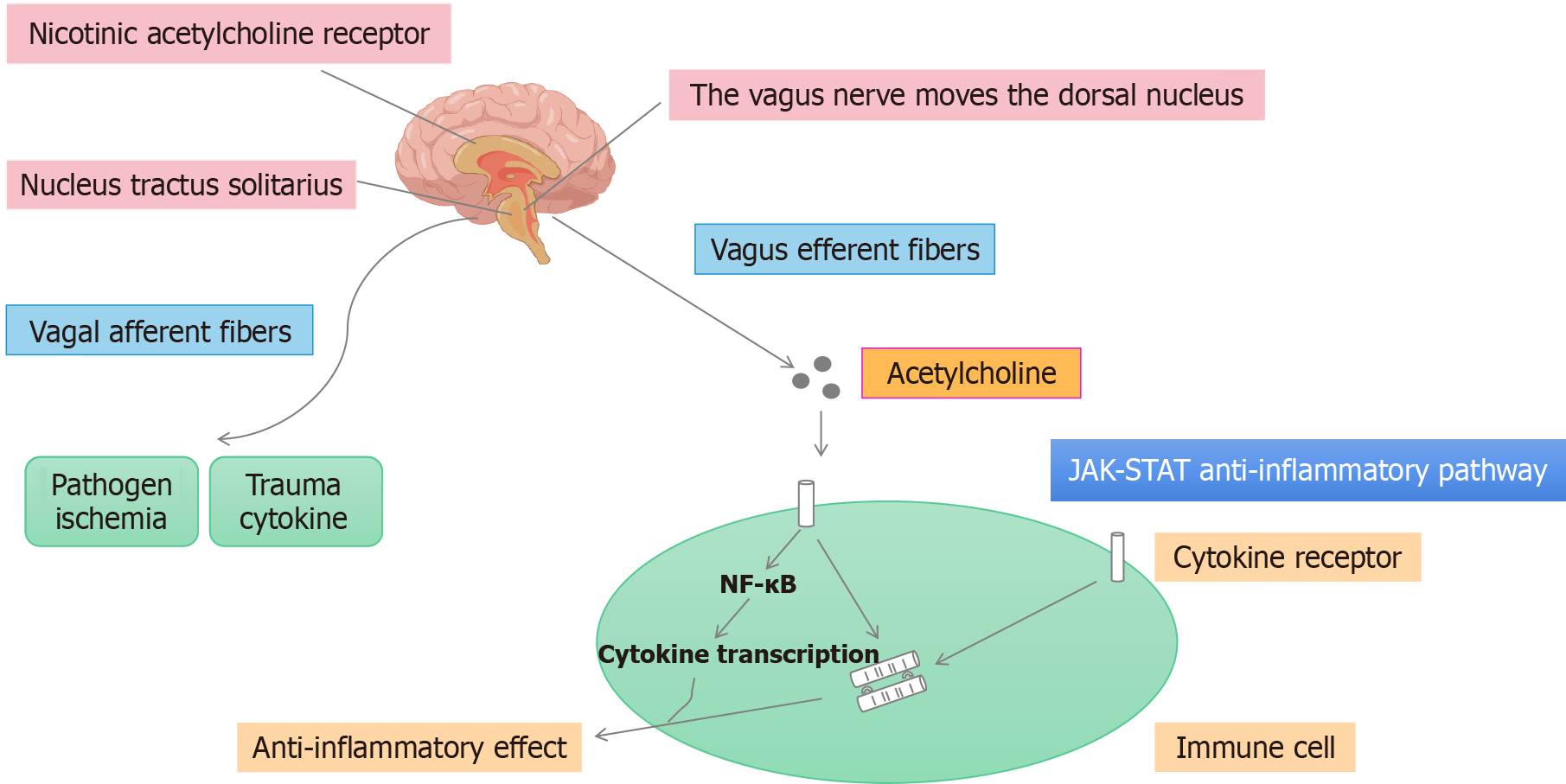

Studies have shown that VNS can inhibit TNF-α production in the spleen and circulating blood of animals with endotoxemia, whereas severing the VN has the opposite effect[34]. Electrical stimulation of the distal vagal trunk can alleviate liver tissue damage caused by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) in animal models of sepsis, and this protective effect depends on the presence of α7nAChR. Percutaneous stimulation of the VN not only decreases the level of TNF-α in the circulating blood of mice with fatal endotoxemia but also inhibits the production of TNF-α and high mobility group protein B1 in the peripheral blood and increases the survival rates of these animals. Studies have shown that the parasympathetic autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays an important role in immune regulation[35]. This neuroimmune interaction is mediated by the release of norepinephrine, which in turn stimulates ACh release by memory T cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway.

There are two main categories of cholinergic receptors, namely, muscarinic (M) and nicotinic (N) receptors. Different cholinergic agonists and antagonists have been applied to primary cultured macrophages in vitro, and the anti-inflammatory effects of ACh have been found to be mediated mainly by N receptors. α7nAChR, an N receptor that can bind to α-cirrotoxin, can be expressed in macrophages, white blood cells, endothelial cells and epithelial cells in the peripheral circulation and tissues[36]. α7nAChR is expressed in the nervous system, neurons and different glial cells, and these cells are considered the targets of cholinergic anti-inflammatory effects. In vitro and in vivo experiments have confirmed that α7nAChR is necessary for cholinergic transmission to inhibit the release of TNF-α by macrophages and is a key receptor in the CAIP that decreases cytokine synthesis[37]. Therefore, it is important to develop agonists that target α7nAChR to inhibit the release of TNF-α and other inflammatory cytokines in inflammatory diseases. ACh reduces the amount of TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6 and IL-18 released by macrophages stimulated with LPS but does not significantly affect the release of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10[38]. This effect of ACh is mediated by nicotinic ACh receptors, which are also sensitive to snake venom. Subsequent studies have shown that α7nAChR is the receptor responsible for this effect[39]. In vitro experiments have revealed that nicotine acts on the surface of macrophages to inhibit LPS-induced TNF release and that VNS does not have anti-inflammatory effects in endotoxemic mice with α7nAChR knockout[40]. Therefore, α7nAChR is necessary for the anti-inflammatory effect of VNS and is an important component of the CAIP. VNS-mediated inhibition of TNF-α does not require the activation of M receptors on immune cells[41].

ACh directly interacts with α7nAChR expressed by splenic macrophages, which is inconsistent with the original hypothesis of a direct role for VN fibers and splenic macrophages, which suggests that the VN regulates the innate immune response indirectly by activating adrenergic neurons in the paravertebral ganglia[42]. According to this hypothesis, VNS exerts anti-inflammatory effects only in mice with intact and innervated spleens. Considering the important role of macrophages in a variety of intestinal diseases, such as postoperative ileus, gastroparesis, and intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury, the CAIP may be an exciting and novel focus for research on the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases[43].

CHOLINE REGULATES INTESTINAL MACROPHAGES

The neurons in the ENS are diverse. Pseudounipolar and bipolar sensory neurons in the submucosal plexus can sense pressure on and stretching of the mucosal surface. Moreover, like excitatory and inhibitory motor neurons, interneurons in the ENS process information and generate impulses. The intestinal VN is innervated by multiple efferent fibers. The injection of tracers into the dorsal motor nucleus of the VN showed that the efferent fibers of the VN interact directly with the postganglionic synapses of the ENS rather than with the neurons of the prevertebral ganglia[44]. The ENS is a complex neural system that is composed of 200-500 million neurons in humans and is also known as the "cerebellum of the intestine". The ENS mainly regulates gastrointestinal functions, including gastrointestinal movement, secretion, blood flow, mucosal growth and local immune regulation[45]. In the intestinal wall, nerve fibers are closely associated with immune cells, especially macrophages, which may engage in complex interactions mediated by neurotransmitters, cytokines, and hormones[46]. The cell bodies of cholinergic excitatory nerves are scattered in submucosal and intermuscular nerve clusters, and the nerve endings supply the gastrointestinal longitudinal and annular muscles or form synaptic connections with other neurons in the nerve plexus. After it is released, ACh activates M cholinergic receptors on smooth muscle and N cholinergic receptors on ganglion cells, causing gastrointestinal muscle excitation and facilitating the intestinal peristaltic reflex[47]. In smokers with intestinal inflammatory diseases, α7nAChR has been shown to regulate inflammation by modulating Mφ polarization, suggesting that nicotine may exacerbate symptoms in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) but not in those with ulcerative colitis (UC).

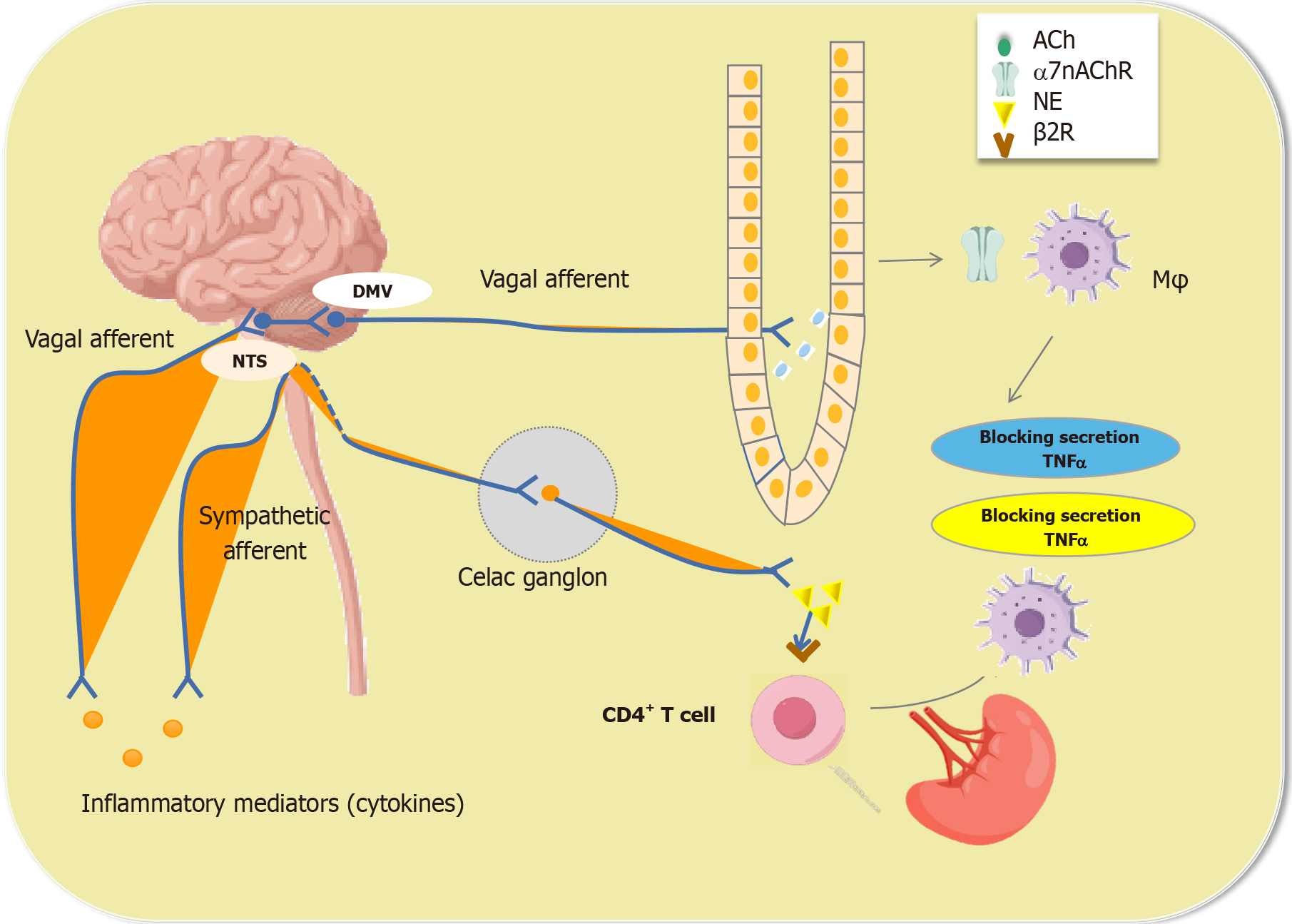

Inflammatory mediators released locally during inflammation activate sensory nerves and release signals to the nervous system. In turn, efferent nerves transmit nervous system signals to the periphery, and the mediators released by the peripheral nerves affect immune regulation and cause inflammatory responses. Therefore, the nervous system can rapidly sense and regulate the inflammatory response of peripheral tissues and release cytokines to target locally mediated immune cells to restore immune balance. For example, intestinal inflammation caused by Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) infection or intestinal examination injury can activate neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS)[48]. Oral administration of C. jejuni can induce the expression of c-Fos, an indirect marker of the activity of vagus sensory neurons and brainstem vagus neurons. Similarly, c-Fos expression in the NTS is observed in the context of surgery-induced inflammation in the intestine[49]. Motor neurons in the dorsal nucleus of the VN adjacent to the site of inflammation are also activated, which is consistent with the presence of a basic inflammatory reflex. The concept of the "inflammatory reflex" also applies to the gut, and cholinergic regulation of intestinal inflammation has indeed been demonstrated in postileus models. A response of the serosal layer is triggered by the activation of macrophages during intestinal surgery, resulting in impaired neuromuscular function[50]. Notably, in a mouse model of postoperative ileus, VNS was shown to inhibit Mφ activation, prevent serosal layer inflammation, and promote the recovery of gastrointestinal regulatory function. This effect is mediated mainly by the activation of cholinergic intestinal neurons that innervate muscle and are adjacent to macrophages[51] (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Acetylcholine regulates intestinal macrophage function.

Mφs: Macrophages; Ach: Acetylcholine; α7nAChR: Α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor α; NTS: Nucleus tractus solitarius.

However, whether VNS exerts similar anti-inflammatory effects on the Lp has still not been fully established. As in macrophages, cholinergic nerve fibers are found in intestinal monocytes in the submucosal plexus and Lp. Interestingly, efferent vagal nerve endings do not synapse on intestinal macrophages but do synapse on intestinal neurons, suggesting that intestinal neurons may regulate the function of intestinal macrophages[52]. Taken together, these findings suggest that interactions between the nervous and immune systems offer new opportunities and challenges for treating immune-related intestinal diseases.

ACH REGULATES IBD-RELATED PATHOGENIC MECHANISMS

IBD

Autonomic dysfunction induces changes related to increased sympathetic tone and decreased vagal tone, increasing the risk of developing chronic inflammatory diseases. IBD patients often present with impaired parasympathetic function (i.e., decreased vagal tone) and increased sympathetic function, resulting in a change in the proinflammatory environment[53]. In support of this hypothesis, one study revealed a positive correlation between sympathetic tone (i.e., serum neuropeptide Y levels) and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity (i.e., serum cortisol levels) in healthy individuals but not in IBD patients[54]; instead, IBD patients exhibited increased sympathetic tone and decreased HPA axis activity. Notably, oral steroid medications may affect sympathetic tone and HPA axis activity. In addition, long-term chronic colonic inflammation in patients with active IBD may suppress cortisol release, leading to decreased resistance to mucosal damage[55]. Given that the function and anti-inflammatory action of the VN are impaired in IBD patients, restoring vagosympathetic nerve function may be key for reducing IBD recurrence.

Studies have shown that abnormal autonomic nervous function may be involved in IBD onset[56]. VN activity is decreased in UC patients, whereas sympathetic nerve activity is increased in CD patients[57]. Another study revealed increased VN activity in both UC and CD patients[58]. Moreover, many experiments have shown that VN activation has anti-inflammatory effects in IBD. Animal studies have shown that VN transection increases the IBD disease activity index (DAI), gross score, histological score, and proinflammatory cytokine levels in mice and that peripheral or central acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors significantly reduce intestinal inflammation in rats and mice. Depressive behavior in mice results in lower levels of ACh in the gut and increased susceptibility to intestinal inflammation, and tricyclic antidepressants prevent this damage[59]. Studies have shown that the anti-inflammatory effects of VNS are mediated through a macrophage- or spleen-dependent mechanism[60]. To date, there are no clinical data supporting the notion that VN transection increases the incidence of intestinal inflammation. However, circumstantial evidence supports that VNS has anti-inflammatory effects in IBD. The precise relationship between VN function and IBD still needs to be confirmed.

Vagosympathetic nerve function and HPA activity can be assessed by measuring heart rate variability (HRV) and serum cortisol levels, respectively. Autonomic function can be assessed in humans by measuring HRV, and related data revealed that decreased VN activity in healthy individuals and patients with heart disease is significantly associated with indicators of the degree of systemic inflammation such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and the levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), TNF-α, and IL-10[61]. Individual differences in autonomic nervous function can also be used as predictors of UC disease activity[62]. Studies have shown that HRV has value in predicting the prognosis of several chronic inflammatory diseases[63]. Patients with CD reportedly have higher serum TNF-α and salivary cortisol levels than patients with high vagal tone[64]. This supports the hypothesis that a decrease in nerve tone has an inhibitory effect on cytokines and contributes to the intermittent release of inflammatory mediators[65]. Notably, ANS balance is differentially regulated among IBD patients because of differences in emotional regulation and coping styles. Active coping is associated with lower vagal tone in patients with CD and higher vagal tone in patients with UC[66]. Therefore, IBD patients should be differentiated according to their disease type, and certain psychological factors should be considered when HRV is used as a diagnostic marker. However, HRV could serve as an important biomarker for identifying patients who might benefit from medication or electrical stimulation targeting the CAIP. In such cases, repeated monitoring of vagal tone could help determine treatment efficacy.

Animal studies of IBD

Studies have shown that autonomic dysfunction can lead to increased inflammation in animals with experimental colitis[67]. Some studies have shown that vagotomy (VGX) can reduce resistance to oral drugs[68]. This difference may be related to the reduced proliferation of T regulatory (Treg) cells in mesenteric lymph nodes and the intestinal Lp. Furthermore, DSS-treated mice subjected to VGX are more likely to develop colitis than those not subjected to VGX. In mouse models of DSS-induced acute colitis, mice subjected VGX present more consistent weight loss and fecal scores than do mice not subjected to VGX. Similarly, VGX has been found to increase disease activity in DSS- and DNBS-induced models of colitis. In addition, on day 9 of VGX-induced colitis, myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity and colonic proinflammatory cytokine levels were found to be increased[69]. Interestingly, however, VN function is gradually restored to normal levels at different time points after VGX, suggesting that the ENS continues to adapt to a reduction in the number of vagal afferents, in turn regulating immune balance. If the VN is completely damaged, other anti-inflammatory mechanisms may be activated[70].

VNS inhibits TNF-α production in the spleen and circulating blood of endotoxemic animals, whereas severing the VN has the opposite effect[71]. Electrical stimulation of the distal vagal trunk can alleviate liver tissue damage caused by CLP in septic animals, and the protective effect depends on the presence of α7nAChR[72]. In mice with fatal endotoxemia, percutaneous VNS not only reduces the level of TNF-α in the circulating blood but also inhibits the production of HMGB1 in the peripheral blood and increases the survival rate of the animals[73].

In addition, the transfer of macrophages from mice subjected to VGX to Mφ colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) 1-deficient mice results in increased levels of colon inflammation, suggesting that macrophages play an important role in the anti-inflammatory action of the VN[74]. Notably, there was no exacerbation of colitis in vagotomized M-CSFop/op mice, which further illustrates the critical role of macrophages in the CAIP. Recent studies have shown that the proinflammatory effects of VGX are associated with a decrease in the number of Treg cells in the colon and spleen, suggesting that macrophages may negatively affect Treg development in individuals with colitis[75].

ELECTROPHYSIOLOGICAL VNS FOR THE TREATMENT OF IBD

Animal research

CAIP activation via VNS has become a popular subject of research and may represent a new method to treat IBD. To date, many clinical reports have shown that CAIP activation plays an important role in various diseases and has some practical value in the clinical treatment of immune-mediated IBD. Selecting an appropriate VNS frequency for patients with different diseases is highly important. Generally, high-frequency (20-30 Hz) VNS, which is most commonly used to treat epilepsy and depression, is believed to activate VN afferent fibers, whereas low-frequency (approximately 10 Hz) VNS can activate VN efferent fibers, thus exerting anti-inflammatory effects[76]. Therefore, lower-frequency VNS is usually chosen to treat IBD in animal models. Initially, only VN efferent fibers and the CAIP were believed to be involved in mediating the effects of VNS[77]. In animal experiments, low-frequency VNS (1-10 Hz) has been shown to exert an anti-inflammatory effect by activating VN efferent fibers and the CAIP[78]. Moreover, studies have shown that proximal VN ligation does not reduce the anti-inflammatory effects of VNS, indicating that the afferent pathway does not play an important role in these effects[79]. However, studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging to study neural connections in rats subjected to VNS have shown that VNS-induced cerebellar deactivation is related to known NTS-cerebellar projections[80], emphasizing the role of VN afferents in the effect of VNS.

The role of ACh in the CAIP is indisputable. In the spleen, norepinephrine released by nerves stimulates memory T cells to release ACh. ACh then binds to α7nAChR expressed by macrophages to inhibit the release of TNF-α in macrophages of the spleen, thereby inhibiting inflammation[81]. Therefore, increasing the release of ACh or prolonging its half-life may have anti-inflammatory effects similar to those of VNS[82]. The role of AChE in colitis has been confirmed in clinical models[83]. In many cholinergic pathways in the central and peripheral nervous systems, AChE can rapidly hydrolyze ACh to terminate neurotransmission[84]. The inactivation of AChE leads to the accumulation of ACh and increased stimulation of N and M cholinergic receptors. For example, galantamine (GAL) is a reversible competitive inhibitor of AChE that can cross the blood-brain barrier and increase cholinergic activity in the brain and is widely used to treat Alzheimer's disease[85]. Studies have shown that GAL can activate VN afferent fiber activity and that its anti-inflammatory effects are related to M cholinergic receptor-mediated CAIP activity in the brain[86]. In addition, GAL alleviates DNBS- and DSS-induced mucosal inflammation in colitis, which is associated with decreased levels of MHCII and the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α by splenic CD11c+ cells[87].

Another therapeutic strategy for promoting CAIP activity in inflammatory diseases is the use of cholinergic agonists that specifically activate α7nAChR; animal studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach[88]. The administration of the α7nAChR agonist nicotine significantly increases survival in endotoxemic and septic animals and inhibits the development of experimental UC and skin inflammation[89]. Randomized controlled clinical trials have shown that nicotine therapy can significantly alleviate UC exacerbation[90]. However, the exact mechanism underlying the anti-inflammatory effect of nicotine has not been demonstrated in humans, and the protective effect of nicotine mediated by a reduction in cytokine release has been demonstrated only in cell culture and animal experiments[91]. Notably, the clinical use of nicotine in patients is limited by its toxic side effects, so the development of low-toxicity α7nAChR-specific agonists is important for achieving cholinergic anti-inflammatory effects in clinical settings.

CAIP activity in the central nervous system was also demonstrated through the use of the M1 ACh receptor agonist McN-A-343[92]. In a recent study, central administration of McN-A-343 was found to significantly ameliorate DAIs in DNBS- and DSS-induced colitis and reduce IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels[93]. This effect is mediated by the functional interaction between DCs and CD4+CD25- T cells regulated by α7nAChR and NF-κB signaling, which is dependent on the VN and splenic nerve. Notably, the anti-inflammatory effect of McN-A-343 is abolished in splenectomized mice, suggesting that there may be a pathway connecting the VN and the spleen that regulates intestinal inflammation[94].

Interestingly, consistent with earlier reports on the effect of VNS in sepsis, cholinergic regulation of macrophages by VNS is mediated by α7nAChR in the small intestine and β2nAChR in the stomach[95]. However, the role of these nicotine receptors in colitis remains controversial. Intestinal inflammation in DSS-induced acute colitis models can be continuously reduced by the injection of nicotine, a nonselective N ACh receptor agonist[96]. Multiple studies have shown that male α7nAChR-/- mice are more likely to develop DSS-induced colitis than male wild-type mice are, but female α7nAChR-/- mice have a DAI similar to that of female wild-type mice[97]. Conversely, treatment with α7nAChR agonists (e.g., choline, PHA-543613, and GTS-21) ameliorates DSS-induced colitis and alleviates clinical symptoms, whereas other specific α7nAChR agonists (e.g., AR-R17779 and GSK1345038A) exacerbate colon inflammation[98]. In addition, VNS may exert effects on mucosal immune homeostasis through molecular mechanism other than the inhibition of inflammation in the outer mucosa and spleen. Therefore, further research on the efficacy of α7nAChR agonists in the treatment of IBD in patients is needed[99].

CAP55 has been used as the lead compound in cholinergic compound screening, and its therapeutic dose (12 mg/kg) is much lower than its LD50 (40 mg/kg); therefore, it is considered safe to use[100]. CNI-1493 is a newly discovered drug that inhibits systemic inflammation and has entered a phase II clinical trial for the treatment of CD[101]. Preclinical trials have shown that CNI-1493 has protective effects in various animal models of inflammatory diseases, including endotoxin shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, pancreatitis, experimental allergic encephalitis, stroke, rheumatoid arthritis, and glucan sulfate-induced enteritis[102]. Moreover, recent investigations have provided preliminary support for a central anti-inflammatory effect of CNI-1493 through the CAIP, thus offering a basis for the development of new systemic anti-inflammatory drugs[103].

In addition to pharmacologically targeting CAIP, VNS can also ameliorate various diseases. For example, studies have confirmed that chronic VNS has good therapeutic potential for treating TNBS-induced colitis. Specifically, electrical stimulation of the VN for 3 hours per day (1 mA, 5 Hz, pulse width 500 microseconds; on for 10 seconds, off for 90 seconds; continuous cycles) alleviates the symptoms of TNBS-induced colitis, including weight loss, bleeding, and diarrhea, and significantly decreases the DAI[104]. These effects are mediated by the inhibition of NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase nuclear translocation. In addition, compared with mice subjected to sham stimulation, mice subjected to VNS for 6 days were found to exhibit significant reductions in colonic inflammation, including the inhibition of inflammatory infiltration and ulcer healing[105]. This effect was associated with progressive recovery of the colon and significant reductions in TNF-α and IL-6 levels[106]. Interestingly, in a mouse model of oxazolidone-induced colitis, a single application of VNS of the cervical VN significantly alleviates intestinal inflammation and increases survival, and VNS reduces the serum levels of IL-6, CXCL1, and TNF-α and inhibits the expression of IL-6 and CXCL1 in the colon in oxazolidone-induced colitis[107]. Similarly, VNS decreases the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in intestinal monocytes from patients with DSS-induced colitis and increases the expression of Arg1, thus improving the DAI. Taken together, these studies confirm the potential of VNS as a new treatment for IBD[108].

To date, VNS has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of refractory epilepsy and depression, and given the anti-inflammatory effects of VNS, many animal experiments and clinical studies have been performed to evaluate its efficacy in treating IBD. Several studies have shown that VNS for 3 hours per day for 5 days can reduce weight loss and inflammatory marker levels in rats with TNBS-induced colitis[109]. Moreover, VNS treatment for 3 hours per day for 6 days reduces the DAI, histological score, MPO activity, and TNF-α, IL-6 and NF-κBp65 Levels in a rat model of TNBS-induced colitis. VNS reduces the DAI and plasma TNF-α, IL-10, IL-6, and MP0 Levels in rats with TNBS-induced colitis through the autonomic pathway. In addition, VNS was shown to be effective in treating oxazolidone-induced colitis, which is another animal model of IBD[110].

Clinical research

The value of VNS for the treatment of immune-mediated diseases has received substantial attention among researchers over the past 20 years. The classic treatment modality involves the use of an invasive VNS device consisting of a pulse generator, bipolar VNS wires, a laptop computer, programming software, programming wands, and hand-held magnets. Invasive VNS requires two small incisions; the pulse generator is implanted in the upper left side of the chest, and bipolar wires are usually wrapped around the left VN in the neck[111]. The clinician uses a laptop, programming software and a programming wand to program the stimulator. The patient applies the magnet and controls the frequency of stimulation after the pulse generator is implanted. It is generally believed that the left VN is a superior target to the right VN for this treatment because the right VN has a greater impact on cardiovascular function[112]. Although stimulation of the right VN has been used to treat epilepsy and although it seems that stimulation of the right VN is as effective as stimulation of the left VN is, the ability of right VN to interfere with heart function or breathing has not been fully elucidated. In general, invasive VNS is safe and well tolerated. The most common adverse effects are hoarseness, cough and shortness of breath, with voice/speech changes, pain, throat or laryngeal spasms, headache, insomnia and poor swelling occurring less commonly, and these adverse effects are usually temporary[113].

To date, however, there have been few reports regarding electrophysiological stimulation of the VN as a therapy for IBD patients. In one study, a patient with CD received low-frequency VNS (frequency, 10 Hz; pulse width, 500-1000 milliseconds; intensity, 0.5-1.5 mA; stimulation time, 30 seconds after 5 minutes)[114]; at the 6-month follow-up, the patient exhibited significant alleviation of clinical symptoms, a decreased DAI, and decreased levels of inflammatory indicators such as CRP and calcineurin, as well as relief of endoscopic manifestations[115]. This apparent clinical effect may have been related to increased parasympathetic tone (i.e., HRV). VNS has also been shown to be safe and well tolerated. The most common adverse effects include voice changes, cough, dyspnea, nausea, and headache; however, these adverse effects are temporary. In a study of 7 patients with active CD who received chronic low-frequency VNS for 6 months, 5 patients showed significant alleviation of clinical symptoms and biological and improvements in endoscopic findings, while 2 patients dropped out of the study at the 3-month follow-up due to worsening disease[116]. In another study, chronic VNS (frequency of 10 Hz, pulse width of 250 milliseconds, current of 0.5-2.0 mA for 60 seconds) was performed on 5 active CD patients, 2 of whom experienced clinical remission after 16 weeks of stimulation; the observed remission may have been related to reduced calcineurin levels and endoscopic scores. Although these studies have shown that VNS can have good therapeutic effects in patients with active IBD, considering the small sample size and limited research methods, the influence of the placebo effect and other factors cannot be excluded; therefore, increasing the sample size and conducting in-depth research at multiple centers are necessary in future studies[117].

In recent years, the development of noninvasive VNS technology has also attracted widespread attention; the safety and tolerability of this approach are substantially greater than those of invasive VNS, and the method is convenient and easier to use, thus promoting its clinical application. Noninvasive VNS, including transauricular VNS (taVNS) and transcervical VNS (tcVNS), can effectively treat epilepsy, migraine, depression and other diseases; does not require surgical implantation of electrodes or pulse generators; and is safer and more convenient than invasive VNS[118]. In taVNS the auricular branch of the VN, which innervates the conchal cavity and the conchal boat, is stimulated. In tcVNS, VN fibers in the carotid sheath are stimulated. The efficacy of nVNS in the treatment of inflammation has been explored in animal and clinical studies, and taVNS in rats has been shown to inhibit LPS-induced inflammation through the CAIP via a mechanism mediated by α7nAChR[119]. Another study revealed that taVNS prevents endotoxemia and reduces the release of IL-6 and TNF-α in mice. A study revealed that in healthy individuals, tcVNS reduces the levels of cytokines and chemokines in the blood, and taVNS reportedly decreases sympathetic nerve activity. Therefore, clinical studies evaluating the anti-inflammatory effects of percutaneous VNS in patients with IBD are needed[120].

The voltage and frequency needed to activate the CAIP during VNS are lower than those needed for cardiac VN activation, suggesting that VNS may be a practical and effective method for regulating the inflammatory response in human diseases[121]. Since VNS is an approved clinical therapy for the treatment of epilepsy and depression in patients resistant to other treatments, this strategy has practical clinical value for regulating systemic or local inflammatory responses. In clinical studies, selective α7nAChR agonists have been evaluated primarily as treatments for schizophrenia and Alzheimer's disease. Only a few studies have shown an anti-inflammatory effect for these substances[122]. Notably, the selective α7nAChR agonist GTS-21 reduces LPS-stimulated whole-blood factor production in healthy individuals and inhibits cytokine release more effectively than nicotine does in patients with severe sepsis. However, in a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial, GTS-21 (150 mg given 3 times daily for 3 days) did not significantly reduce cellular inflammation in healthy male (n = 14) endotoxemic patients (intravenously administered LPS from Escherichia coli O:113 at a dose of 2 ng/kg)[123].

Activation of the CAIP by cholinergic agonists can also control the inflammatory response in sepsis patients. In vitro and in vivo experiments have shown that nicotine can effectively reduce the levels of TNF-α and HMGB1 in sepsis patients[124]. The α7nAChR-specific agonists GTS-21 and choline have similar effects. Although VNS significantly reduces the levels of TNF-α in the plasma, liver and spleen, it has limited anti-inflammatory effects on lung tissue in a mouse endotoxemia model. The anti-inflammatory effect of α7nAChR agonists is more extensive than that of VNS[125]. In addition, CNI-1493, oxytocin and growth hormone-releasing peptide can activate the central cholinergic system, normalize VN activity, and downregulate the expression of inflammatory mediators in sepsis patients. Some data have shown that cholinesterase inhibitors (physostigmine and neostigmine) can decrease the inflammatory response in septic animals. However, high doses of cholinesterase inhibitors do not increase survival in animal models, although the specific reasons for this are unclear[126]. At present, cholinesterase inhibitors are believed to increase the concentration of ACh and promote cholinergic activity by reducing cholinesterase activity, ultimately exerting anti-inflammatory effects.

CONCLUSION

Important progress in elucidating the pathogenesis of IBD has been made in recent years. To date, several studies have revealed the pathogenesis of abnormal immune responses in patients with IBD, in which macrophages are key players in long-term chronic inflammation. Macrophages are a special type of phagocyte that play a crucial role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis and movement. In the gut, macrophages are divided into different subgroups according to their location in the parietal layer and are closely associated with the microenvironment. The VN exerts anti-inflammatory effects through afferent and efferent fibers in different ways, and dysregulation of VN function plays an important role in the pathogenesis of IBD. VNS is a safe bioelectrical neuroregulatory technology that can restore the balance between sympathetic nerve and VN activation and prevent obvious adverse reactions to drugs for IBD. Relevant studies have evaluated the efficacy of VNS in treating IBD and explored the mechanisms underlying the effect of VNS. These studies provide a theoretical basis for the clinical application of VNS in IBD treatment. Current research is focused on the development of noninvasive VNS technologies to provide safer and more tolerable treatments for IBD. While preliminary data suggest that percutaneous VNS may hold value in treating IBD, further research is needed to better demonstrate the applicability of VNS for treating chronic inflammatory diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank our colleagues at the Institute of Digestive Disease for their help and support in this research.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Novelty: Grade A, Grade A, Grade A, Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade A, Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Panda PK, MD, Professor, India; Wu SC, PhD, China; Zhao K, MD, Professor, China S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang L