Published online Nov 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i41.111449

Revised: August 4, 2025

Accepted: September 26, 2025

Published online: November 7, 2025

Processing time: 127 Days and 18.5 Hours

Autoimmune gastritis (AIG) is frequently associated with one or more comorbid conditions, among which type I gastric neuroendocrine tumors (gNETs) warrant significant clinical concern. However, risk factors for the development of gNETs in AIG populations remain poorly defined.

To characterize the clinical and endoscopic profiles of AIG and identify potential risk factors for gNETs development.

In this single-center cross-sectional study carried out at a tertiary hospital, 303 patients with AIG over an 8-year period were retrospectively categorized into gNETs (n = 116) and non-gNETs (n = 187) groups. Endoscopic and clinical pa

Among the 303 patients with AIG, 116 had gNETs and 187 did not. Compared with the non-gNETs group, patients in the gNETs group were younger (54.3 years vs 60.6 years, P < 0.001), had higher rate of vitamin B12 deficiency (77.2% vs 55.8%, P < 0.001), lower pepsinogen I (4.3 ng/mL vs 7.4 ng/mL, P < 0.001) and pepsinogen I/II ratios (0.7 vs. 1.1, P < 0.001), and lower prior Helicobacter pylori infection rate (3.4% vs 21.4%, P < 0.001). Endoscopically, the gNETs group showed a lower incidence of oxyntic mucosal remnants, hyperplastic polyps, and patchy antral redness. The predictive model incorporating age, prior Helicobacter pylori infection, vitamin B12 level, gastric hy

Patients with AIG or gNETs exhibit specific clinical and endoscopic features. The predictive model demonstrated favorable discriminative ability and may facilitate risk stratification of gNETs in patients with AIG.

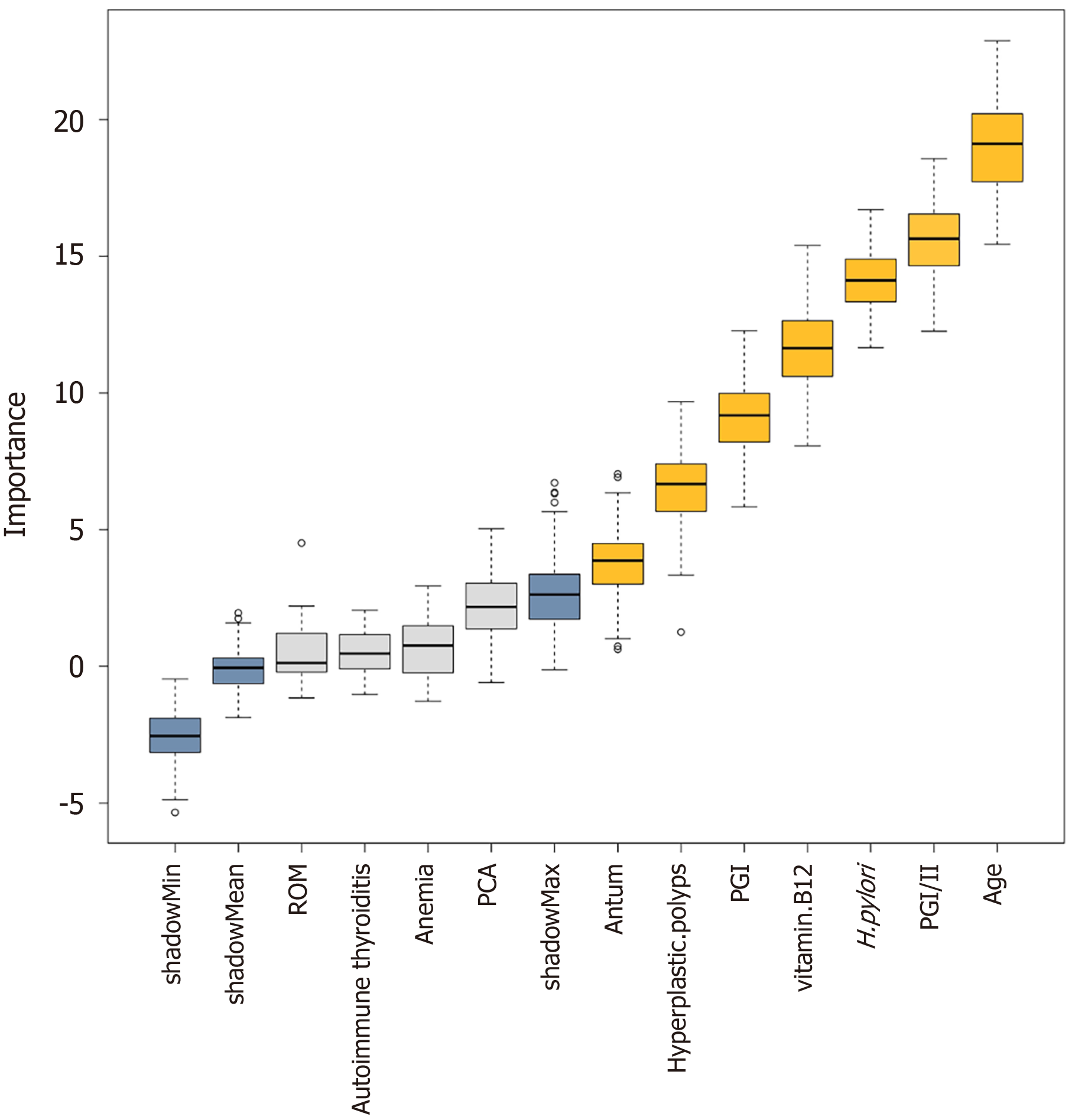

Core Tip: To explore the potential risk factors for gastric neuroendocrine tumors (gNETs) in autoimmune gastritis, 303 patients (116 with and 187 without gNETs) were analyzed. Patients in gNETs group were younger, had a higher rate of vitamin B12 deficiency, lower pepsinogen I levels and pepsinogen I/II ratios, fewer prior Helicobacter pylori infections, oxyntic mucosal remnants, gastric hyperplastic polyps, and patchy antral redness. The features selected using the Boruta algorithm included age, Helicobacter pylori infection status, vitamin B12 level, gastric hyperplastic polyps, and patchy antral redness. The identified predictors may facilitate risk stratification of gNETs in patients with autoimmune gastritis.

- Citation: Li YM, Guo WJ, Deng C, Luo J, Shi YF, Zhu D, Wei QL, Zhang MG, Du SY, Tan HY. Risk assessment of type I gastric neuroendocrine tumors based on endoscopic and clinical features of autoimmune gastritis. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(41): 111449

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i41/111449.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i41.111449

Autoimmune gastritis (AIG) is a chronic and progressive inflammatory disorder of the gastric oxygen mucosa induced by an autoimmune response. It predominantly targets the parietal cells, thereby resulting in hypochlorhydria and vitamin B12 deficiency[1]. AIG is frequently associated with one or more comorbidities such as iron-deficiency anemia, pernicious anemia, neuropathy, gastric hyperplastic polyps, and type I gastric neuroendocrine tumors (gNETs)[2]. Specifically, hypochlorhydria stimulates gastrin secretion by gastric antral G cells. Continuous secretion of gastrin leads to enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell hyperplasia, which in turn contributes to the pathogenesis of gNETs[3-5]. The prevalence of gNETs among patients ranges from 0.4% to 7%. The prognosis of type I gNETs is generally favorable after endoscopic or surgical tumor resection[6]. Nevertheless, the recurrence rate remains notably high, reaching 41.2%, as per data from our hospital’s previous report[7]. Studying the risk factors for gNETs is important for early diagnosis and formulation of screening strategies, especially for patients in primary hospitals or those with limited access to repeated gastroscopy.

Currently, research on the risk factors of type I gNETs in patients with AIG is relatively scarce. A study on the North American population reported that among patients with AIG, those with gNETs had significantly higher gastrin levels than those without gNETs (1859.8 pg/mL vs 679.5 pg/mL, P < 0.001)[8]. Vitamin B12 or iron deficiency and higher levels of thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) are associated with gNETs in patients[9,10]. Vanoli et al[11] demonstrated that severe ECL cell hyperplasia, consisting of more than six chains of linear hyperplasia per millimeter, and ECL cell dysplasia increased the risk of gNETs in patients with AIG. These studies either included a relatively small number of patients or did not collect endoscopic imaging data using a novel descriptive method. Therefore, their conclusions require further validation.

In 2022, Japanese researchers summarized the typical endoscopic manifestations in patients with AIG, namely reverse atrophy, remnants of oxyntic mucosa (ROM), sticky adherent dense mucus, hyperplastic polyps, and antral findings[12,13]. These typical endoscopic features were integrated into the diagnostic criteria for AIG by 2023[14]. However, their application in patients with AIG, particularly in historical cases, remains limited, and their predictive value for the risk of gNETs development is uncertain. In this study, patients with AIG were classified into gNETs and non-gNETs groups, and their clinical and endoscopic features were analyzed. These analyses aimed to predict gNETs risk in patients with AIG and facilitate the early identification of high-risk individuals.

This study used a cross-sectional design. Patient data from the China-Japan Friendship Hospital, China, between January 2017 and January 2025, were retrospectively collected in January 2025 through outpatient and inpatient medical records as well as the endoscopic database. AIG diagnosis was based on the criteria established in 2023 by workshops of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society and the Committee of the AIG Research Project[14]. Confirmed cases were defined as patients meeting the AIG criteria via endoscopic and/or histological examination and testing positive for gastric autoantibodies, including parietal cell antibodies (PCA) and/or intrinsic factor antibodies (IFAb). ECL cell nodules are diagnosed as gNETs when they exceed 0.5 cm in diameter or infiltrate beyond the submucosa, according to the 2010 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the digestive system. Eligible patients aged 18-85 years were diagnosed with AIG. Patients with missing key data (gastroscopy, pathology, PCA, and IFAb test results), without gastroscopy images, or with unclear images were excluded. All patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled.

The medical records of all patients were reviewed. General patient information was collected, including sex, age, concomitant diseases, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection status, and administration of vitamin B12 and iron supplements.

The results of the following tests were determined: Serum PCA [indirect immunofluorescence, negative (< 1:100), weak positive (1:100), positive (> 1:100)], IFAb [chemiluminescence immunoassay, negative (< 1.2 AU/mL), weak positive (1.2-1.53 AU/mL), positive (≥ 1.53 AU/mL)], serum vitamin B12 (pmol/L), gastrin-17 (chemiluminescence immunoassay, pmol/L), pepsinogen I (PGI, ng/mL), the ratio of PGI/II, as well as ferritin (ng/mL), hemoglobin (HGB, g/L), thyroid-stimulating hormone (μIU/mL), homocysteine (μmol/L), TPOAb (IU/mL), thyroglobulin antibody (IU/mL), white blood cell (WBC, × 109/L), mean corpuscular volume (fL), and platelet count (× 109/L).

Information related to H. pylori infection was collected from medical records, including the results of H. pylori evaluation using the 13C urea breath test, serum antibody test, pathological examination, treatment for H. pylori, and endoscopy findings. H. pylori infection status was defined as follows: (1) Probably uninfected: No eradication history and negative antibody test, urea breath test, or pathological examination, and corpus-restricted inflammation and antrum-sparing atrophy were observed; (2) Previously infected: With a history of positive antibody test or pathological examination; (3) Currently infected: Positive antibody test without eradication history or positive pathological examination; and (4) No records: No eradication history or detection records. The status of H. pylori was confirmed based on endoscopic findings.

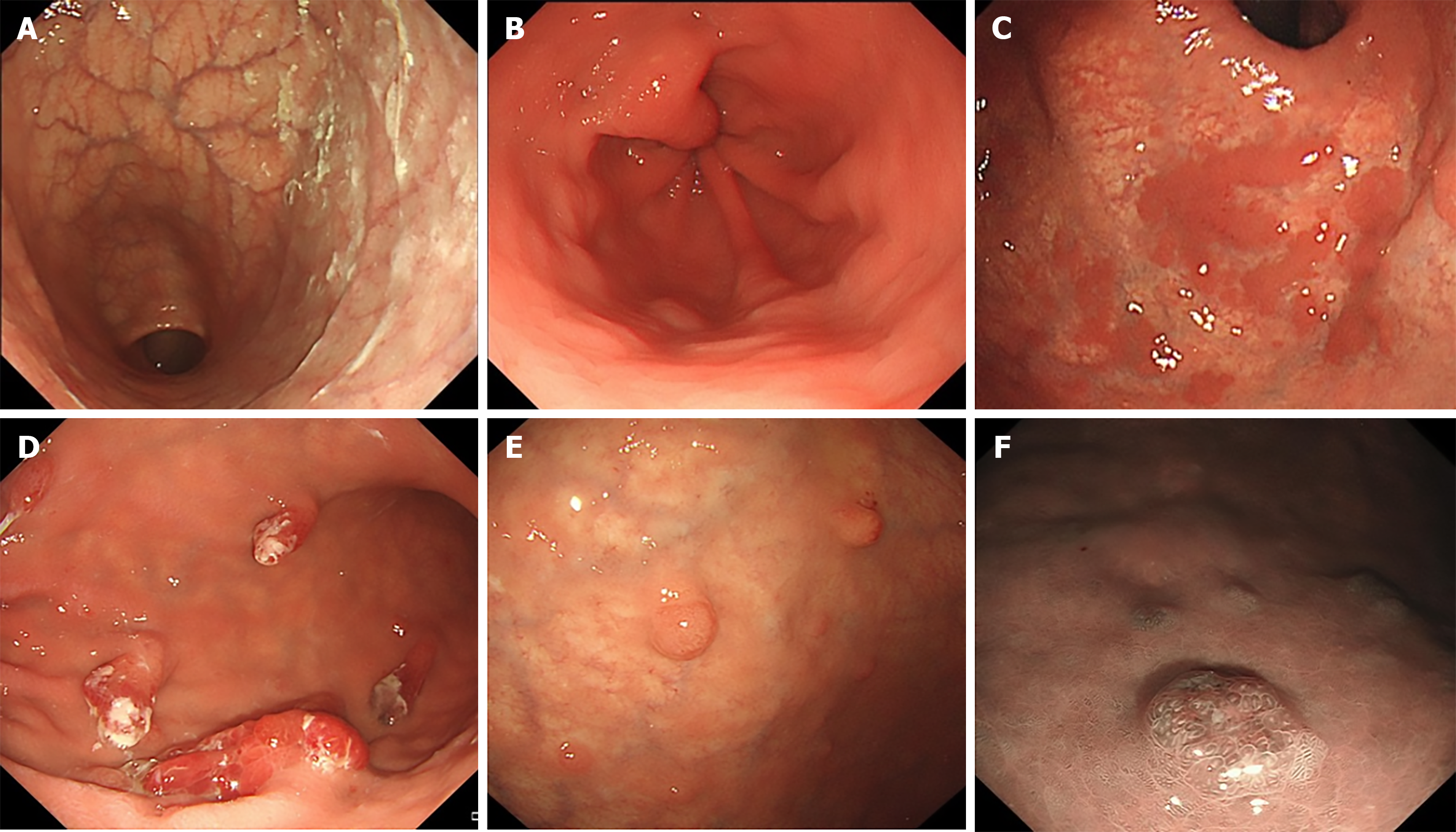

All patients in this study underwent endoscopy at China-Japan Friendship Hospital. All endoscopy images were thoroughly reevaluated and double-checked in a blinded manner by two physicians with extensive endoscopic experience. They independently analyzed all gastroscopy images to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the endoscopic results. The following manifestations under gastroscopy were evaluated and recorded: Reverse atrophy, sticky adherent dense mucus, ROM, types of ROM (flat localized, pseudo-polyp-like, island-shaped, extensive, and granular), hyperplastic polyps, gNETs, and findings in the gastric antrum, including patchy redness, red streaks, and a circular wrinkle-like pattern of the mucosa.

Patients with AIG were categorized into two groups: GNETs and non-gNETs. All collected data, including demographic information, comorbid diseases, endoscopic appearance, and laboratory test results, were examined. Missing data were handled by using an imputation method with chained equations[15]. Quantitative data showing a normal distribution was presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons between two groups were performed using the t-test. The median (interquartile range) was used to describe data with a skewed distribution, and the Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to compare differences. For qualitative data, rate (95% confidence interval), χ2 test, or the exact probability method were used to compare the differences between groups. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical comparisons of ROM types because of the small sample sizes of some subtypes. The Boruta algorithm was employed for variable selection to identify the influential predictors. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to evaluate risk factors. The discriminative ability of the model in recognizing gNETs was evaluated using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 4.2.2) and the Free Statistics analysis platform (version 2.1.1, Beijing, China). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

A total of 467 patients with suspected AIG were identified using the outpatient and endoscopy database. Among them, 330 patients met the diagnostic criteria for AIG. A further 12 patients with missing laboratory data and nine patients with unclear endoscopic images were excluded. Ultimately, 303 patients with AIG were enrolled in this study, of whom 116 were in the gNETs group and 187 in the non-gNETs group. Given that our hospital’s oncology department is a renowned research center for gNETs, the proportion of patients with gNETs is considerably high. Table 1 shows the general patient data. The mean age of the patients was 54.3 years in the gNETs group and 60.6 years in the non-gNETs group (P < 0.001). Among all patients with AIG, 64% were female and 36% were male.

| Variables | Total (n = 303) | Non-gNETs group (n = 187) | gNETs group (n = 116) | P value |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 58.2 ± 11.7 | 60.6 ± 11.5 | 54.3 ± 10.8 | < 0.001b |

| Sex | 0.421 | |||

| Male | 109 (36.0) | 64 (34.2) | 45 (38.8) | |

| Female | 194 (64.0) | 123 (65.8) | 71 (61.2) | |

| Concomitant diseases | ||||

| Gastric mucosal neoplasia | 10 (3.3) | 8 (4.3) | 2 (1.7) | 0.327 |

| Tumors other than gastric mucosal neoplasia | 32 (10.6) | 24 (12.8) | 8 (6.9) | 0.102 |

| Anemia | 142 (46.9) | 78 (41.7) | 64 (55.2) | 0.022a |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 88 (40.9) | 36 (34) | 52 (47.7) | 0.04a |

| Other autoimmune diseases | 21 (7.0) | 15 (8.1) | 6 (5.2) | 0.337 |

| H. pylori | < 0.001b | |||

| Probably uninfected | 240 (79.2) | 131 (70.1) | 109 (94) | |

| Previously infected | 44 (14.5) | 40 (21.4) | 4 (3.4) | |

| Currently infected | 12 (4.0) | 9 (4.8) | 3 (2.6) | |

| No records | 7 (2.3) | 7 (3.7) | 0 (0) | |

| B12 supplement | 163 (53.8) | 86 (46) | 77 (66.4) | 0.001b |

| Iron supplement | 77 (25.4) | 43 (23) | 34 (29.3) | 0.22 |

In terms of comorbid diseases, 10 patients (3.3%) had gastric mucosal neoplasia, and 21 patients (6.9%) had tumors other than gastric mucosal neoplasia, with no significant difference between the two groups. These tumors included colorectal cancer (five cases), thyroid cancer (eight cases), breast cancer (two cases), and one case each of cervical cancer, esophageal cancer, mediastinal squamous cell carcinoma, lung cancer, endometrial cancer, and ovarian cancer. A total of 142 patients (46.9%) had anemia, with the gNETs group showing a significantly higher proportion (55.2%). Patients with autoimmune thyroiditis accounted for 40.9%, with a higher proportion (47.4%) in the gNETs group (P = 0.04), and 21 patients (7%) had other autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (five cases), vitiligo (four cases), type I diabetes mellitus (three cases), Sjogren’s syndrome (two cases), idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (two cases), and one case each of autoimmune hepatitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, primary biliary cholangitis, oral lichen planus, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis, necrotizing myositis, and IgA kappa monoclonal gammopathy.

A total of 191 patients underwent pathological examination for H. pylori evaluation, 85 underwent breath tests, 12 underwent serum antibody assays, and 15 reported a history of infection, without specifying the testing modality. Among the 44 patients with prior H. pylori treatment, nine were considered refractory eradication cases. H. pylori status was determined by integrating endoscopic assessments for all subjects. Among these patients, most (79.2%) were classified as probably uninfected, 14.5% were previously infected, 4.0% were currently infected, and 2.3% had no records. Among all the patients, 53.8% received vitamin B12 supplementation, with a significantly higher proportion in the gNETs group (66.4%). Iron supplementation was administered to 25.4% of patients, with no significant intergroup difference.

Endoscopic findings are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. Among the patients enrolled in this study, 98.3% showed reverse atrophy, and 35.0% showed sticky mucus during endoscopy, with no significant difference between the two groups. In patients with ROM, flat localized (35.2%), pseudopolyp-like (22.2%), island-shaped (5.6%), extensive (33.3%), and granular (3.7%) types showed no intergroup differences. Gastric antrum findings showed that 52.1% of patients had relatively normal mucosa, 20.5% had patchy redness, 12.5% had red streaks, and 14.9% showed circular wrinkle-like patterns. More patients in the gNETs group showed red streaks and circular wrinkle-like patterns, whereas more patients in the non-gNETs group showed patchy redness (P < 0.001). Gastric hyperplastic polyps were present in 27.3% of the non-gNETs patients, which was significantly higher than that in 9.5% of the gNETs patients (P < 0.001).

| Variables | Total (n = 303) | Non-gNETs group (n = 187) | gNETs group (n = 116) | P value |

| Reverse atrophy | 298 (98.3) | 182 (97.3) | 116 (100) | 0.161 |

| Sticky adherent dense mucus | 106 (35.0) | 65 (34.8) | 41 (35.3) | 0.917 |

| ROM | 54 (17.8) | 42 (22.5) | 12 (10.3) | 0.007b |

| Types of ROM | 0.734 | |||

| Flat localized | 19 (35.2) | 14 (33.3) | 5 (41.7) | |

| Pseudopolyp-like | 12 (22.2) | 10 (23.8) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Island-shaped | 3 (5.6) | 3 (7.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Extensive | 18 (33.3) | 14 (33.3) | 4 (33.3) | |

| Granular | 2 (3.7) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Findings in antrum | < 0.001b | |||

| Relatively normal | 158 (52.1) | 93 (49.7) | 65 (56) | |

| Patchy redness | 62 (20.5) | 53 (28.3) | 9 (7.8) | |

| Red streak | 38 (12.5) | 16 (8.6) | 22 (19) | |

| Circular wrinkle-like pattern | 45 (14.9) | 25 (13.4) | 20 (17.2) | |

| Hyperplastic polyps | 62 (20.5) | 51 (27.3) | 11 (9.5) | < 0.001b |

The laboratory test results are presented in Table 3. There were statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of PCA, vitamin B12, WBC, HGB, PGI, and PGI/II. Among them, 92.5% had positive or weakly positive PCA. The concentration of vitamin B12 in the non-gNETs group was higher than that in the gNETs group (P < 0.001). Accordingly, the proportion of patients with vitamin B12 deficiency (< 133 pmol/L) was significantly higher in the gNETs group than in the non-gNETs group (77.2% vs 55.8%, P < 0.001). Serum gastrin-17 Levels were measured in 74 patients (22 patients in the gNETs group). The median gastrin-17 Level was 55.3 (40.0-71.4) pmol/L in the non-gNETs group and 49.8 (35.3-62.1) pmol/L in the gNETs group (P = 0.257).

| Variables | Total (n = 303) | Non-gNETs group (n = 187) | gNETs group (n = 116) | P value | Missing |

| PCA | 0.019a | 9 (2.97) | |||

| Positive (≥ 1:160) | 144 (48.8) | 89 (49.7) | 55 (47.4) | ||

| Weak positive (1:100) | 129 (43.7) | 71 (39.7) | 58 (50) | ||

| Negative (< 1:100) | 22 (7.5) | 19 (10.6) | 3 (2.6) | ||

| IFAb (AU/mL) | 0.572 | 11 (3.63) | |||

| Positive (≥ 1.53) | 135 (46.2) | 85 (47.5) | 50 (44.2) | ||

| Weak positive (1.2-1.53) | 63 (21.6) | 35 (19.6) | 28 (24.8) | ||

| Negative (< 1.2) | 94 (32.2) | 59 (33) | 35 (31) | ||

| Gastrin-17 (pmol/L) | 51.3 (6.9, 64.4) | 55.3 (40.0, 71.4) | 49.8 (35.3, 62.1) | 0.257 | 229 (75.58) |

| Vitamin B12 (pmol/L) | < 0.001b | 22 (7.26) | |||

| ≤ 133 | 184 (64.3) | 96 (55.8) | 88 (77.2) | ||

| 133-223 | 41 (14.3) | 27 (15.7) | 14 (12.3) | ||

| > 223 | 61 (21.3) | 49 (28.5) | 12 (10.5) | ||

| TPOAb or TGAb positive | 111 (51.9) | 52 (50) | 59 (53.6) | 0.595 | 89 (29.37) |

| Other antibody positive | 50 (17.0) | 37 (20.6) | 13 (11.4) | 0.042a | 9 (2.97) |

| IFAb (AU/mL) | 1.3 (1.2, 32.8) | 1.3 (1.2, 57.5) | 1.3 (1.2, 11.5) | 0.257 | 11 (3.63) |

| Vitamin B12 (pmol/L) | 124.0 (80.0, 221.0) | 152.0 (83.0, 275.0) | 102.0 (79.5, 151.2) | < 0.001b | 22 (7.26) |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 23.1 (9.2, 63.4) | 30.6 (9.1, 68.8) | 19.6 (9.2, 39.6) | 0.077 | 23 (7.59) |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 5.5 ± 1.6 | 5.7 ± 1.6 | 5.3 ± 1.4 | 0.035a | 15 (4.95) |

| HGB (g/L) | 125.1 ± 25.1 | 122.1 ± 25.9 | 129.6 ± 23.2 | 0.012a | 9 (2.97) |

| MCV (fL) | 87.7 ± 10.4 | 88.3 ± 11.9 | 86.8 ± 7.6 | 0.208 | 13 (4.29) |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 224.3 ± 71.2 | 228.0 ± 75.2 | 218.9 ± 64.9 | 0.292 | 18 (5.94) |

| PGI (ng/mL) | 5.9 (3.5, 9.6) | 7.4 (4.3, 16.3) | 4.3 (3.0, 7.0) | < 0.001b | 110 (36.30) |

| PGI/II | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | 1.1 (0.6, 1.6) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) | < 0.001b | 112 (36.96) |

| TSH (μIU/mL) | 2.1 (1.3, 3.4) | 2.1 (1.5, 3.7) | 2.1 (1.3, 3.1) | 0.227 | 86 (28.38) |

| TPOAb (IU/mL) | 26.2 (9.9, 258.0) | 20.0 (9.4, 166.0) | 53.2 (10.2, 357.8) | 0.167 | 90 (29.70) |

| TGAb (IU/mL) | 24.9 (14.7, 102.8) | 23.1 (14.1, 59.7) | 25.0 (15.0, 163.2) | 0.191 | 89 (29.37) |

| HCY (μmol/L) | 11.3 (9.1, 15.8) | 12.3 (9.1, 17.5) | 11.2 (9.1, 14.3) | 0.142 | 149 (49.17) |

Compared with the non-gNETs group, the WBC level was lower, while the HGB level was higher in the gNETs group (129.6 g/L vs 122.1 g/L, P = 0.012). Owing to the susceptibility of blood HGB and WBC counts to fluctuations resulting from vitamin B12/iron supplementation and the significantly higher B12 supplementation in patients with gNETs, these variables were excluded from the risk factor analysis. The value of PGI and PGI/II in the gNETs group were significantly lower than those in the non-gNETs group (4.3 ng/mL vs 7.4 ng/mL, P < 0.001; 0.7 vs 1.1, P < 0.001, respectively). There were no significant differences in the IFAb, ferritin, mean corpuscular volume, thyroid-stimulating hormone, TPOAb, thyroglobulin antibody, or homocysteine levels between the two groups.

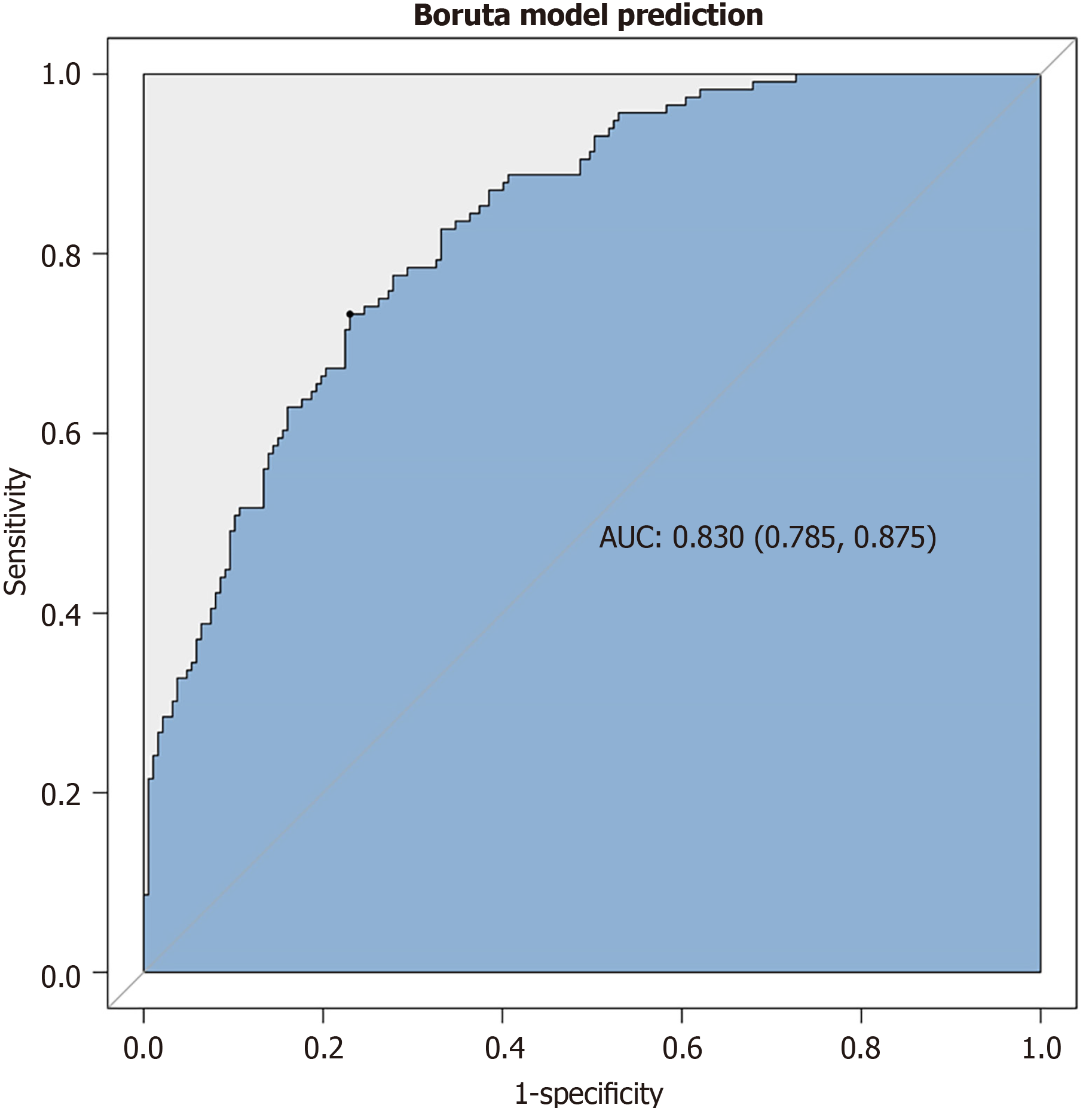

The Boruta algorithm was used to assess the relative significance of multiple variables in forecasting gNETs outcomes based on the disease characteristics of AIG and the results of univariate analysis (Figure 2). The variables are ranked based on their predictive importance. Eight key variables were identified for gNETs discrimination: Age, PGI/II, H. pylori infection status, vitamin B12 Level, PGI, presence of hyperplastic polyps, and antrum findings. Following multivariate analysis, five variables were found to be statistically significant, as shown in Table 4: Age, previous H. pylori infection, vitamin B12, gastric hyperplastic polyps, and patchy redness in the gastric antrum. All patients exhibited an inverse association with gNETs risk (odds ratio < 1). Figure 3 shows the ROC curve of this multivariate model with an area under the curve of 0.830.

| Variables | Crude OR (95%CI) | Crude P value | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted P value |

| Age, years | 0.95 (0.93-0.97) | < 0.001 | 0.95 (0.92-0.97) | < 0.001b |

| PGI/II | 0.3 (0.17-0.5) | < 0.001 | 0.45 (0.2-1.01) | 0.052 |

| H. pylori infection status | ||||

| Probably uninfected | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Previously infected | 0.12 (0.04-0.35) | < 0.001 | 0.11 (0.03-0.37) | < 0.001b |

| Currently infected | 0.23 (0.06-0.79) | 0.02 | 0.24 (0.06-1.01) | 0.051 |

| Vitamin B121, pmol/L | 0.96 (0.94-0.98) | < 0.001 | 0.97 (0.94-1) | 0.02a |

| PGI (ng/mL) | 0.91 (0.87-0.95) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.93-1.05) | 0.737 |

| Hyperplastic polyps | 0.28 (0.14-0.56) | < 0.001 | 0.3 (0.13-0.66) | 0.003b |

| Findings of antrum | ||||

| Relatively normal | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Patchy redness | 0.24 (0.11-0.53) | < 0.001 | 0.39 (0.16-0.95) | 0.038a |

| Red streak | 1.97 (0.96-4.03) | 0.065 | 1.59 (0.69-3.67) | 0.275 |

| Circular wrinkle-like pattern | 1.14 (0.59-2.23) | 0.692 | 0.99 (0.44-2.23) | 0.984 |

Type I gNETs are significant in patients with AIG[16,17]. However, it remains unclear which patients with AIG are more susceptible to developing gNETs, particularly regarding endoscopic features. In this study, data from a single center over 8 years were analyzed, and endoscopic characteristics were reevaluated in all patients. The results revealed significant differences in endoscopic and clinical characteristics between the gNETs and non-gNETs groups. These predictive variables may facilitate risk stratification for gNETs development in patients with AIG.

Endoscopic evaluation revealed that the gNETs group had less ROM and hyperplastic polyps, with antral red streaks and circular wrinkle-like patterns more prevalent and patchy redness less common than in the non-gNETs group. Although both hyperplastic polyps and gNETs may be linked to gastric mucosal hyperplasia caused by elevated gastrin levels[18], the findings of this study suggest that these two lesions may have distinct pathogenic mechanisms, and further research is required to elucidate these differences.

ROM was more prevalent in the non-gNETs group than in the gNETs group, suggesting that ROM may be associated with a lower risk of gNETs development. To the best of our knowledge, no similar findings have been previously reported. Japanese researchers proposed a classification for the extent of AIG atrophy based on the proportion of ROM in the gastric oxyntic area[19]. ROM typically indicates that a portion of the normal acid-secreting glands remain functional in the gastric mucosa, which may be associated with lower gastrin levels and a subsequent lower risk of gNETs. Whether the ROM area is negatively correlated with the occurrence of gNETs requires further investigation. Clinically, compared to the non-gNETs group, patients in the gNETs group had lower levels of PGI and PGI/PGII, a higher percentage of autoantibodies, anemia, vitamin B12 deficiency, and vitamin B12 supplementation.

Patients in the gNETs group had a lower mean age at enrollment, suggesting that AIG in this subgroup either had an earlier onset or was diagnosed earlier, although the exact reason remains unclear. AIG is often underdiagnosed in clinical practice and on endoscopy. Certain factors may facilitate the diagnosis of AIG in patients with concurrent gNETs, whereas patients without gNETs may be more prone to a delayed diagnosis. In this study, patients with AIG and type I gNETs exhibited lower PGI levels, PGI/II ratios, and a lower incidence of ROM, indicating more severe gastric atrophy. As nodular lesions, gNETs are readily identifiable during gastroscopy, which may improve the endoscopic diagnostic rate for AIG. These patients also have a higher rate of vitamin B12 deficiency and anemia, thus potentially presenting with more symptoms that prompt earlier medical evaluation. On the other hand, AIG pathogenesis involves multiple factors, including genetic susceptibility, immune dysregulation, and H. pylori infection. In this study, patients with AIG and gNETs had a higher incidence of autoimmune thyroiditis and a lower rate of prior H. pylori infection, suggesting that AIG patients with distinct pathogenesis may present with varied disease progression, rendering certain patients with AIG more susceptible to gNETs. Further studies are needed to elucidate the pathogenesis and progression of patients with AIG[2].

The association between H. pylori infection and risk of gNETs in patients with AIG requires further clarification. In the present study, H. pylori-probably uninfected individuals were more prevalent in the gNETs group, whereas infected patients, particularly those with previous infections, were less prevalent. Mechanistically, H. pylori infection may precipitate oxyntic atrophy, resulting in hypochlorhydria and subsequent hypergastrinemia, which have been found to contribute to the development of gNETs[20,21]. Additionally, H. pylori can modulate the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway to promote gastrin expression[22], with modest gastrin levels and uncommon carcinoids. In a previous study, H. pylori infection was detected in 28.7% of AIG cases and was not associated with gNETs[23]. Furthermore, H. pylori eradication has been reported to improve AIG by reducing associated antibody levels and gastric mucosal atrophy and has proven effective in treating early-stage AIG[24-26]. This study, along with previous research, suggests that eradicating H. pylori might protect against gNETs in patients with AIG. This study included a multivariate model of factors associated with gNETs. Patients who were previously infected with H. pylori, were older, had higher vitamin B12 Levels, had gastric hyperplastic polyps, and exhibited patchy redness in the antrum were at a lower risk of developing gNETs. The ROC curve showed a high discrimination ability of the gNETs prediction model (area under the curve 0.830).

This study has some limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional, single-center study. Some clinical data were absent from the archived records, which inevitably introduced a selection bias. Second, the generalizability of the predictive model to broader populations is limited by the high proportion of gNETs cases in this study due to referral center bias. Such bias could potentially overestimate the predictive accuracy of the model. Future multicenter studies with population-based sampling are required to validate these findings. Third, the diagnosis of AIG in this study predominantly depended on the endoscopic findings and laboratory test results. Consequently, patients with early stage or suspected AIG were excluded. Moreover, indirect immunofluorescence was employed for the PCA test in this study, and its accuracy may be lower than that of fluorescent enzyme immunoassay. Fourth, owing to the absence of routine gastrin testing in hospital laboratories, gastrin-17 measurements were only performed in a subset of patients, resulting in a relatively small sample size. Future studies incorporating unified gastrin measurements may enhance our understanding of this disease. Fifth, the gNET predictive model proposed in this study is exploratory and requires validation through prospective studies with longitudinal follow-up data to assess its prognostic value and long-term clinical relevance. Finally, an external validation in an independent patient cohort is required to confirm the applicability of the model in diverse settings and populations.

This study investigated the clinical and endoscopic data of patients with AIG with and without gNETs. The results suggest an association between prior H. pylori infection, older age, higher vitamin B12 Levels, gastric hyperplastic polyps, patchy antral erythema, and lower gNET risk in this cohort. These findings may aid in the risk stratification of patients with AIG, warranting further validation for their potential clinical utility in gNET screening and surveillance.

| 1. | Vavallo M, Cingolani S, Cozza G, Schiavone FP, Dottori L, Palumbo C, Lahner E. Autoimmune Gastritis and Hypochlorhydria: Known Concepts from a New Perspective. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:6818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen Y, Ji X, Zhao W, Lin J, Xie S, Xu J, Mao J. A real-world study on the characteristics of autoimmune gastritis: A single-center retrospective cohort in China. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2025;49:102556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vannella L, Sbrozzi-Vanni A, Lahner E, Bordi C, Pilozzi E, Corleto VD, Osborn JF, Delle Fave G, Annibale B. Development of type I gastric carcinoid in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1361-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cockburn AN, Morgan CJ, Genta RM. Neuroendocrine proliferations of the stomach: a pragmatic approach for the perplexed pathologist. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20:148-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Boeriu A, Dobru D, Fofiu C, Brusnic O, Onişor D, Mocan S. Gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms and precursor lesions: Case reports and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e28550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hoibian S, Ratone JP, Solovyev A, Dahel Y, Mitry E, Poizat F, Guiramand J, Caillol F, Giovannini M. Effective endoscopic management of gastric neoplastic complications in patients with autoimmune gastritis: results of a monocentric study of 88 patients. Ann Gastroenterol. 2025;38:163-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen YY, Guo WJ, Shi YF, Su F, Yu FH, Chen RA, Wang C, Liu JX, Luo J, Tan HY. Management of type 1 gastric neuroendocrine tumors: an 11-year retrospective single-center study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jove A, Lin C, Hwang JH, Balasubramanian V, Fernandez-Becker NQ, Huang RJ. Serum Gastrin Levels Are Associated With Prevalent Neuroendocrine Tumors in Autoimmune Metaplastic Atrophic Gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025;120:1140-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lenti MV, Miceli E, Lahner E, Natalello G, Massironi S, Schiepatti A, Zingone F, Sciola V, Rossi RE, Cannizzaro R, De Giorgi EM, Gregorio V, Fazzino E, Gentile A, Petrucci C, Dilaghi E, Pivetta G, Vanoli A, Luinetti O, Paulli M, Anderloni A, Vecchi M, Biagi F, Repici A, Savarino EV, Joudaki S, Delliponti M, Pasini A, Facciotti F, Farinati F, D'Elios MM, Della Bella C, Annibale B, Klersy C, Corazza GR, Di Sabatino A. Distinguishing Features of Autoimmune Gastritis Depending on Previous Helicobacter pylori Infection or Positivity to Anti-Parietal Cell Antibodies: Results From the Autoimmune gastRitis Italian netwOrk Study grOup (ARIOSO). Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:2408-2417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li B, Jiang H, Cai C, Chen H. TPOAb indicates neuroendocrine tumor in autoimmune gastritis: A retrospective study of 91 patients. Am J Med Sci. 2025;369:183-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vanoli A, La Rosa S, Luinetti O, Klersy C, Manca R, Alvisi C, Rossi S, Trespi E, Zangrandi A, Sessa F, Capella C, Solcia E. Histologic changes in type A chronic atrophic gastritis indicating increased risk of neuroendocrine tumor development: the predictive role of dysplastic and severely hyperplastic enterochromaffin-like cell lesions. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1827-1837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kishino M, Nonaka K. Endoscopic Features of Autoimmune Gastritis: Focus on Typical Images and Early Images. J Clin Med. 2022;11:3523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Terao S, Suzuki S, Yaita H, Kurahara K, Shunto J, Furuta T, Maruyama Y, Ito M, Kamada T, Aoki R, Inoue K, Manabe N, Haruma K. Multicenter study of autoimmune gastritis in Japan: Clinical and endoscopic characteristics. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Kamada T, Watanabe H, Furuta T, Terao S, Maruyama Y, Kawachi H, Kushima R, Chiba T, Haruma K. Diagnostic criteria and endoscopic and histological findings of autoimmune gastritis in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:185-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Buuren SV, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations inR. J Stat Soft. 2011;45:1-67. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3242] [Cited by in RCA: 3278] [Article Influence: 218.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shah SC, Piazuelo MB, Kuipers EJ, Li D. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Atrophic Gastritis: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1325-1332.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 64.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 17. | Saund MS, Al Natour RH, Sharma AM, Huang Q, Boosalis VA, Gold JS. Tumor size and depth predict rate of lymph node metastasis and utilization of lymph node sampling in surgically managed gastric carcinoids. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2826-2832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hongo M, Fujimoto K; Gastric Polyps Study Group. Incidence and risk factor of fundic gland polyp and hyperplastic polyp in long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy: a prospective study in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:618-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Maruyama Y, Yasuda K, Baba S, Yoshii S, Kageoka M, Ohata A, Terai T, Hoshino H, Inagaki K, Inui W, Baba K, Maruyama T. [Endoscopic diagnosis of disease stage of autoimmune gastritis using a proposed autoimmune gastritis atrophic stage]. Stomach Intest. 2024;59:34-46. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Dacha S, Razvi M, Massaad J, Cai Q, Wehbi M. Hypergastrinemia. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2015;3:201-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hirschowitz BI, Haber MM. Helicobacter pylori effects on gastritis, gastrin and enterochromaffin-like cells in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and non-Zollinger-Ellison syndrome acid hypersecretors treated long-term with lansoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:87-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gunawardhana N, Jang S, Choi YH, Hong YA, Jeon YE, Kim A, Su H, Kim JH, Yoo YJ, Merrell DS, Kim J, Cha JH. Helicobacter pylori-Induced HB-EGF Upregulates Gastrin Expression via the EGF Receptor, C-Raf, Mek1, and Erk2 in the MAPK Pathway. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Magris R, De Re V, Maiero S, Fornasarig M, Guarnieri G, Caggiari L, Mazzon C, Zanette G, Steffan A, Canzonieri V, Cannizzaro R. Low Pepsinogen I/II Ratio and High Gastrin-17 Levels Typify Chronic Atrophic Autoimmune Gastritis Patients With Gastric Neuroendocrine Tumors. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020;11:e00238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Minalyan A, Benhammou JN, Artashesyan A, Lewis MS, Pisegna JR. Autoimmune atrophic gastritis: current perspectives. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2017;10:19-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Faller G, Winter M, Steininger H, Lehn N, Meining A, Bayerdörffer E, Kirchner T. Decrease of antigastric autoantibodies in Helicobacter pylori gastritis after cure of infection. Pathol Res Pract. 1999;195:243-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kotera T, Nishimi Y, Kushima R, Haruma K. Regression of Autoimmune Gastritis after Eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2023;17:34-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/