Published online Oct 21, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i39.110288

Revised: July 20, 2025

Accepted: September 15, 2025

Published online: October 21, 2025

Processing time: 130 Days and 1.1 Hours

Circumferential prolapsed hemorrhoids (CPHs) necessitate surgical intervention. While Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy (MMH) remains widely used, it compromises functional preservation and associates with significant post

To optimize CPH resection and anal function preservation through comparative efficacy-safety evaluation of TILL vs MMH.

A total of 180 patients were retrospectively reviewed in China. The patients were divided into two groups of 90 based on the surgical methods. The treatment group underwent the TILL procedure, while the control group underwent MMH. The main observation index was the evaluation of clinical efficacy after wound healing. Secondary outcomes included the recurrence rate and wound healing time. Safety measurements were also evaluated.

The TILL group showed a significant difference compared to the MMH group (P = 0.022), indicating better overall treatment effects. The time for wound healing in the TILL group was shorter than that in the MMH group (P = 0.001). Compared to those who underwent MMH, those who underwent TILL experienced significantly reduced postoperative pain, with lower average scores for anal edema and anal stenosis (both P < 0.05).

TILL demonstrates superior efficacy to MMH for advanced CPH, reducing recovery times and postoperative pain, edema, and stenosis while preserving anal function.

Core Tip: This study compared transverse incision with longitudinal ligation procedure (TILL) and Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy (MMH) in 180 grade III/IV circumferential prolapsed hemorrhoid patients. Results showed TILL had superior clinical efficacy (P = 0.022), faster wound healing (P = 0.001), and less postoperative pain, anal edema, and stenosis (all P < 0.05) vs MMH. TILL provided more thorough hemorrhoid removal, shorter recovery, and better anal function preservation. The findings suggest TILL is safer and more effective than traditional MMH for advanced circumferential prolapsed hemorrhoid, reducing complications like pain and stenosis while improving surgical outcomes. TILL represents a significant advancement in hemorrhoidectomy technique.

- Citation: Song XB, Wang YZ, Wang YM, Sun H, Li JN, Ma HF, Li X, Sui TT, Liu RH, Lai LX. Optimizing circumferential prolapsed hemorrhoid surgery: Transverse incision with longitudinal ligation procedure delivers superior radicality compared to Milligan-Morgan technique. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(39): 110288

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i39/110288.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i39.110288

Hemorrhoids are a common disease in proctology. An epidemiological survey in Austria showed that 39% of adults suffer from symptomatic hemorrhoids[1]. In China, the prevalence of anal and rectal diseases among residents aged ≥ 18 years in both urban and rural areas is 50.10%, with hemorrhoids accounting for 98.08%[2]. Circumferential prolapsed hemorrhoids (CPHs) often originate from grade III/IV mixed hemorrhoids and are classified as a severe, with surgery as the most effective treatment method. Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy (MMH) is widely used as a classic surgical technique, but finding a balance between completely removing the lesions and preserving the skin bridge of the anal canal remains a challenge in clinical practice[3]. After years of clinical practice, we found that in the surgical treatment of circumferential hemorrhoids, the MMH technique focuses on preserving the skin bridge but fails to completely remove severe hemorrhoids, resulting in significant postoperative pain, noticeable edema, and prolonged healing time, as well as risks of anal stenosis and anal incontinence[4]. Therefore, our research team conducted a systematic and standardized innovative study on the surgical removal of circumferential hemorrhoids, addressing the shortcomings of MMH and exploring a new balance between complete excision and preservation of the skin bridge, making it more suitable for the treatment of severe circumferential hemorrhoids.

Our research team innovatively proposed the transverse incision with longitudinal ligation procedure (TILL), based on the anal cushion descent theory and the theory of the mother hemorrhoid area, introducing the surgical concept of “dividing one into two and two into four”[5]. Through a transverse incision, TILL allows for precise handling of the hemorrhoidal nodules, while longitudinal ligation preserves the normal anatomical structure of the anal canal, with an emphasis on adjusting anal canal tension as part of a holistic treatment approach. In the surgical treatment of circumferential hemorrhoids, TILL has innovated the incision approach with its horizontal “I” shape design, cleverly addressing pressure at the anal opening, maximizing treatment effectiveness while protecting the physiological and anatomical function of the anus. TILL achieves a balance between aesthetic and therapeutic outcomes for anal health by breaking through key technical challenges, significantly reducing the risk of postoperative pain, edema, stenosis, and other complications. This study reports on the efficacy and safety of the TILL procedure and the traditional MMH procedure in the treatment of grade III/IV CPHs.

A computer-generated block randomization sequence was used to allocate 180 eligible CPH patients (1:1 ratio) to receive TILL (n = 90) or MMH (n = 90), following the guidelines of the Clinical Guidelines for Common Diseases in Proctology of Chinese Medicine[6]. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Patients met the criteria of grade III/IV CPHs; and (2) Aged between 18 and 60 years, with no history of anal surgery. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Severe cardiovascular diseases, liver or kidney dysfunction, or other intestinal and anal disorders; (2) Women who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or menstruating, as well as individuals with a history of epilepsy, severe depression, anxiety, or other mental disorders; and (3) Patients with allergies or scarring.

The treatment group underwent the TILL procedure, and the control group underwent MMH. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants following full disclosure of procedural risks and benefits. All surgical interventions were performed by two board-certified anorectal physicians (> 10 years’ experience in anorectal procedures) adhering to standardized protocols.

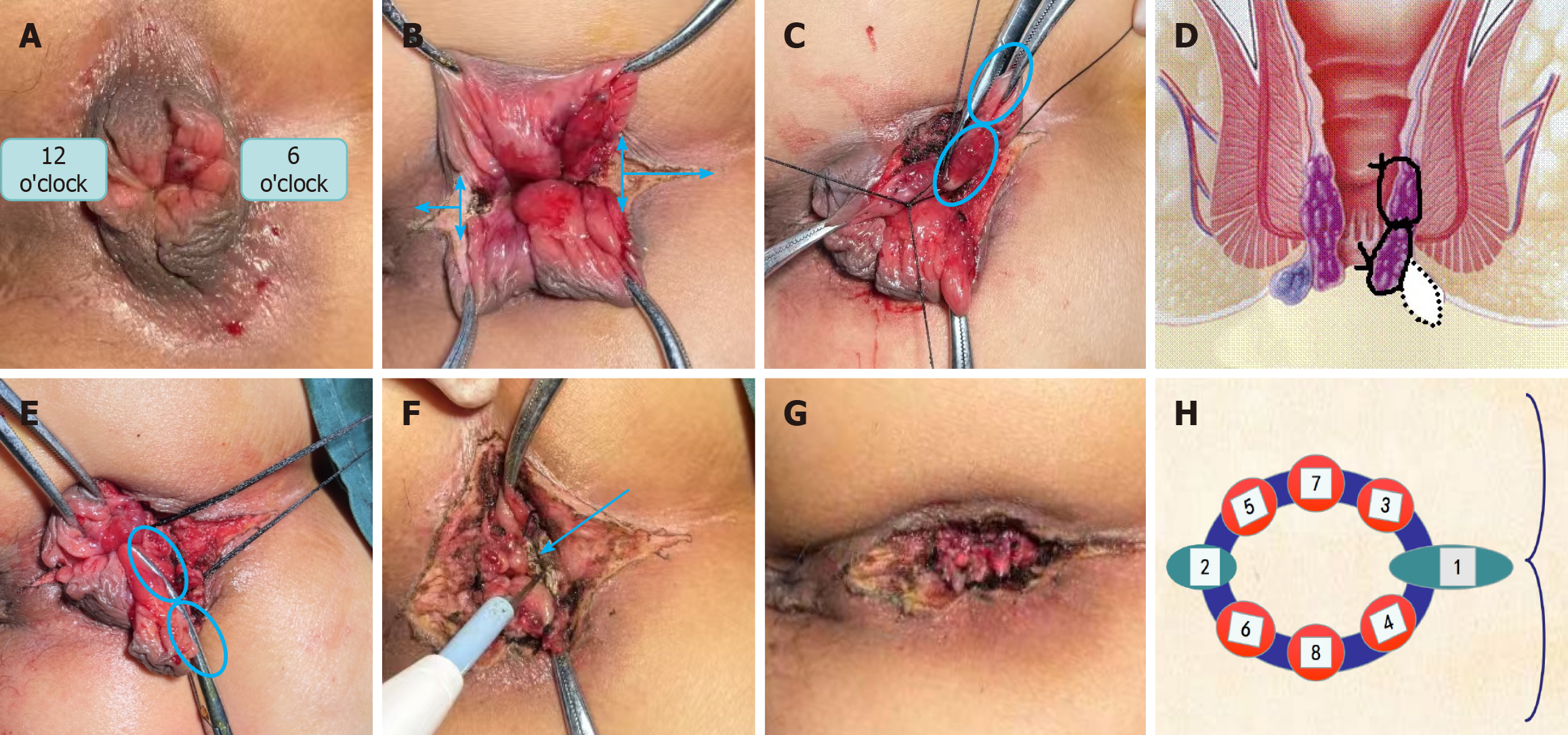

The patient was in a right lateral position. After general anesthesia was established, sterile towels were set up for disinfection, and surgery began after local anesthesia helped relax the anal canal. The main incision was designed at the 6 o’clock and 12 o’clock positions in a horizontal “I” shape with the front and rear of the anal region: (1) Using hemostatic forceps to pull up and down, a larger connected external hemorrhoid at the 6 o’clock position was cut radially and horizontally with an electric scalpel. When cutting into the internal hemorrhoid, the incision extended inward 0.5-1 cm above the dentate line, with the depth depending on the size of the hemorrhoid, which could reach the lower edge of the internal sphincter. The external incision at the 6 o’clock position extended 1-2 cm to the distal end of the external hemorrhoid, and the length of the external was extended based on the size of the external hemorrhoid to prevent early adhesion that could lead to false healing. The same method was used to transversely cut the anterior 12 o’clock connected hemorrhoid, being careful not to cut too deep at the 12 o’clock position where the muscle was thin. This step formed a transverse “I” incision in front and behind the anus, called a horizontal incision, which divided the large hemorrhoid transversely into two (Figure 1A and B); (2) From both sides of the 6 o’clock position, the mixed hemorrhoid was longitudinally separated at the 5 or 7 o’clock position to 0.5-1 cm above the dentate line, ensuring not to cut into the muscle layer while separating. Hemostatic forceps were used to clamp the base of the corresponding hemorrhoid longitudinally, and two No. 7 silk threads were passed through the base under the clamp with a No. 45 round needle to tie a longitudinal ligation with an “8” knot, cutting off the excess ends. This step was called longitudinal ligation, which divided the already horizontally separated hemorrhoid into four, while adjusting the tension of the anal canal in accordance with its anatomical shape, effectively avoiding bleeding during the period of thread detachment (Figure 1C-E); (3) The same method was used to handle the hemorrhoids on both sides of the 12 o’clock transverse incision, with attention to lifting and suspending at the 11 o’clock position. Based on the granular boundary line of the hemorrhoids, other mixed hemorrhoid parts were processed from large to small, ensuring that all ligation points were staggered in the anal canal area to prevent excessive tension at the base of the ligation line, which might have caused too much scarring. At the end of surgery, it was important to adjust the tension and tightness of the anus, which can be done by relaxing both internally and externally at the 6 o’clock transverse incision position (Figure 1F); and (4) Finally, the wound edges were trimmed, ensuring adequate hemostasis, and the look of the wound edges was adjusted (Figure 1G and H).

The control cohort received standard MMH performed in strict accordance with the original technique specifications: Complete excision of hemorrhoidal complexes with ligation at the pedicle base; preservation of intact skin bridges (≥ 0.5 cm width); and primary open wound management as detailed in the foundational surgical atlas[7].

Postoperative treatment was the same in both groups: (1) Antimicrobial prophylaxis: Oral tinidazole (500 mg twice daily) was administered for 7 days to prevent anaerobic infections; (2) Herbal sitz bath: A standardized Chinese herbal decoction (composition: 15 g Cortex Phellodendri, 12 g Herba Portulacae, 12 g Rhizoma Atractylodis, 10 g Tuber Bletillae, 12 g Cortex Moutan, 9 g Pericarpium Zanthoxyli per liter) was applied for 5 minutes following each bowel movement, maintained at 38-40 °C; and (3) Wound treatment: After routine cleaning and disinfection, the wound was bandaged with sterile gauze.

Baseline data collection included basic information such as patient gender, age, duration of illness, and clinical symp

The primary outcome was evaluation of clinical efficacy following wound healing, consisting of four levels: Cured, markedly effective, effective, and ineffective, according to the standards for syndrome diagnosis and efficacy outlined in Traditional Chinese Medicine[6]. Cured: Symptoms disappeared, hemorrhoids disappeared. Markedly effective: Symp

The secondary outcomes included recurrence rate and wound healing time. Recurrence rate was assessed through standardized multimodal surveillance at 6 months postoperatively. This comprehensive evaluation incorporated three validated methods: In-person proctoscopic verification of hemorrhoidal recurrence (classified as grade ≥ II via the Golig

(1) Postoperative pain intensity was assessed using the VAS on postoperative days 1, 3 and 7, with scores from 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximum pain)[8]; (2) On postoperative day 7, anal edema severity was classified into four grades: 0 indicated no edema; 1 described mild localized edema at the wound margin with slight erythema; 2 represented moderate edema with clear demarcation and erythematous margins; and 3 indicated severe widespread edema with tissue induration and dark red margins[9]; (3) On postoperative day 7, anal tenesmus severity was measured using scores from 0 to 3. A score of 0 indicated absence of distension, 1 represented mild tolerable sensation without functional impairment; moderate dis

Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS 26.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous variables, such as age, disease duration, symptom indices, and wound healing time, were reported as mean ± SD. Comparisons between groups for these variables were conducted using the Z test. Categorical data, such as gender, were analyzed with the Pearson χ2 test. In contrast, ranked data, such as efficacy evaluation, were assessed using the χ2 test for trends when applicable. A two-sided P < 0.05 was deemed significant for all analyses.

There were no significant differences in gender, age, and disease duration between the TILL and MHH groups (all P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Variables | TILL group | MMH group | Z/χ2 | P value |

| Gender, male | 39 | 42 | 0.202 | 0.653 |

| Female | 51 | 48 | ||

| Age (years) | 41.71 ± 9.26 | 40.53 ± 9.00 | -0.899 | 0.369 |

| Disease duration (years) | 4.67 ± 2.49 | 4.86 ± 2.38 | -0.685 | 0.494 |

In the TILL group, 82 patients were classified as cured, seven as markedly effective, one as effective, and none as ineffective. In the MMH group, 70 cases were classified as cured, nine as markedly effective, nine as effective, and two as ineffective. There was a significant comparison of the main therapeutic effects between the two groups (χ2 = 9.597, P = 0.022), and the treatment group was superior to the control group (Table 2).

| Grade | TILL group | MMH group | χ2 | P value |

| Ineffective | 0 (0.00) | 2 (2.22) | 9.597 | 0.022 |

| Effective | 1 (1.11) | 9 (10.00) | ||

| Markedly effective | 7 (7.78) | 9 (10.00) | ||

| Cured | 82 (91.1) | 70 (77.80) | ||

| Total | 90 (100.00) | 90 (100.00) |

In the MMH group, two patients (2.22%) had recurrence within 6 months following surgery. No recurrence was observed in the TILL group, and there was no significant difference in the recurrence rate between the two groups (P = 0.155). Wound healing time was significantly shorter in the TILL group compared to the MMH group (33.24 ± 4.06 days vs 35.94 ± 5.38 days; P = 0.001; Table 3).

| Variables | TILL group | MMH group | Z/χ2 | P value |

| Rate of recurrence, n (%) | 0 | 2 (2.22) | 2.022 | 0.155 |

| Healing time (days), mean ± SD | 33.24 ± 4.06 | 35.94 ± 5.38 | -3.216 | 0.001 |

The safety parameters, including postoperative pain, anal edema, anal tenesmus, anal stenosis, and anal incontinence, are detailed in Tables 4 and 5. Postoperative anal pain is an important aspect for evaluating the safety of anorectal surgery and the rapid recovery of the wound surface. The statistical analysis showed significant differences in the VAS scores for anal pain on the postoperative days 1, 3 and 7 between the two groups (P < 0.05). The treatment group demonstrated a significant reduction in postoperative pain. The mean anal edema scores differed significantly between the two groups: 1.02 ± 0.69 for the TILL group and 1.39 ± 0.68 for the MMH group (P = 0.000). The mean anal tenesmus scores were 0.91 ± 0.65 for the TILL group and 0.96 ± 0.63 for the MMH group, indicating no significant difference (P = 0.636). The mean anal stenosis score was 0.14 ± 0.38 in the TILL group, which was significantly lower than 0.39 ± 0.56 in the MMH group (P = 0.001). The mean anal incontinence score was 0.20 ± 0.43 in the TILL group and 0.18 ± 0.41 in the MMH group, with no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.701).

| Group | n | Anal pain (day 1) | Anal pain (day 3) | Anal pain (day 7) |

| TILL group | 90 | 1.01 ± 0.95 | 2.60 ± 1.15 | 4.01 ± 1.12 |

| MMH group | 90 | 1.23 ± 0.84 | 2.98 ± 0.79 | 4.47 ± 1.19 |

| Z | -2.119 | -2.667 | -2.249 | |

| P value | 0.034 | 0.008 | 0.025 |

| Group | Cases | Anal edema | Anal tenesmus | Anal stenosis | Anal incontinence |

| TILL group | 90 | 1.02 ± 0.69 | 0.91 ± 0.65 | 0.14 ± 0.38 | 0.20 ± 0.43 |

| MMH group | 90 | 1.39 ± 0.68 | 0.96 ± 0.63 | 0.39 ± 0.56 | 0.18 ± 0.41 |

| Z | -3.488 | -0.474 | -3.455 | -0.384 | |

| P value | 0.000 | 0.636 | 0.001 | 0.701 |

CPHs are a severe type of hemorrhoids that present challenges in surgical treatment. MMH is considered the gold standard for hemorrhoid surgery[12,13]. However, MMH has limitations in treating grade III/IV circumferential hemorrhoids, which are larger and lack clear boundaries, making it difficult to completely excise the diseased tissue while preserving anal function[14,15]. Following the MMH principle of completely excising the hemorrhoidal tissue may lead to severe pain, prolonged wound healing, and even anal stenosis[16]. However, over-preserving these skin and mucosal bridges can result in incomplete treatment, with leftover skin bridges causing edema, pain, and recurrence of new hemorrhoids, creating a significant psychological and economic burden on patients. Therefore, it is crucial to effectively remove and prevent complications after surgery in the treatment of CPHs, and there is an urgent need for colorectal specialists to rethink the surgical approach and removal techniques for these hemorrhoids[17]. The innovative application of TILL focuses on the overall treatment of hemorrhoids, aiming to remove all hemorrhoidal tissue in one go, while also emphasizing the anterior and posterior release of the anal canal through a linear incision during surgery, which helps prevent anal stenosis and reduces pain and edema after surgery, promoting rapid wound healing.

The results of this study show that TILL outperforms MMH, effectively alleviating symptoms and improving signs. The primary outcomes indicate that TILL has clear advantages over the traditional classic MMH in treating CPHs. Secondary outcomes also suggest that TILL promotes wound healing more quickly and has a lower recurrence rate. The anal area is unique, facing daily defecation stimulation and contamination, and postoperative anal pain is a core concern for both doctors and patients. This study monitored anal pain at three key intervals: On postoperative days 1, 3 and 7. The TILL group had significantly lower VAS scores than the MMH group, which means they experienced less pain and more comfort. Therefore, TILL demonstrates an advantage in reducing postoperative anal pain. Additionally, in terms of evaluating the safety of surgical efficacy, the TILL group had a lower incidence of anal edema and stenosis during recovery compared to the MMH group. This related to how anal canal tension was adjusted during surgery, which allowed for rapid restoration of normal blood and lymphatic flow in the wound area, thereby reducing the occurrence of postoperative anal edema and stenosis. Both groups showed no significant difference in anal tenesmus, possibly due to both groups experiencing relatively severe conditions, with stimulation from the ligation suture ends inside the anal canal and unavoidable defecation stimulation leading to noticeable tenesmus. The Wexner score for anal incontinence is an important safety indicator for anal surgery. In this study, there was no significant difference in Wexner scores between the two groups, and no obvious risk of anal incontinence was found postoperatively, confirming the safety of MMH as a widely used and trusted surgical method. It also supports that while TILL involves partial release of the anal sphincter’s lower edge during surgery, the results after wound healing show that TILL does not carry a risk of anal incontinence.

In this study, the key technology of TILL is the dual control and preventive adjustment of tension between hemor

This study also had limitations. Firstly, participants were enrolled during clinical observation, which may have introduced potential selection bias in this study. Secondly, the study was done at a single center with a small sample size. Finally, the follow-up period was limited to 6 months, requiring long-term follow-up. We hope that future research will include multicenter clinical studies to provide more data support and evidence-based rationale for the implementation of TILL.

This study highlights the advantages of the TILL technique over MMH for the treatment of grade III/IV CPHs. TILL overcomes the limitations of traditional techniques and demonstrates better outcomes, including more complete removal of hemorrhoids, shorter healing time, less postoperative anal pain, and improved anal canal function.

We would like to express our gratitude to Sun ZG, Yang HW, and Jie JZ, for their invaluable guidance, patience and continuous support throughout this research project. Their expert advice, rigorous scrutiny and encouragement have been instrumental in shaping this work and fostering my academic growth.

| 1. | Riss S, Weiser FA, Schwameis K, Riss T, Mittlböck M, Steiner G, Stift A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang HC, Wang L. [Latest epidemiological survey results of anorectal diseases in China released in Beijing]. Zhongguo Yiyao Daobao. 2015;12:175. |

| 3. | Lohsiriwat V. Approach to hemorrhoids. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15:332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Picchio M, Greco E, Di Filippo A, Marino G, Stipa F, Spaziani E. Clinical Outcome Following Hemorrhoid Surgery: a Narrative Review. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:1301-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Li X, Li JN, Yu Q, Lai LX, Ma HF, Wang YM. [Comparison of efficacy and safety between transverse division and longitudinal ligation versus external excision and internal ligation for circular hemorrhoids with grade III-IV internal hemorrhoids]. Jiezhichang Gangmen Waike. 2020;26:298-302. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | China Association of Chinese Medicine. [Clinical Guidelines for Common Diseases in Proctology of Chinese Medicine]. Beijing: China Press of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2012. |

| 7. | Milligan E, Naunton Morgan C, Jones L, Officer R. Surgical anatomy of the anal canal, and the operative treatment of hæmorrhoids. Lancet. 1937;230:1119-1124. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yu Q, Zhi C, Jia L, Li H. Efficacy of Ruiyun procedure for hemorrhoids combined simplified Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy with dentate line-sparing in treating grade III/IV hemorrhoids: a retrospective study. BMC Surg. 2021;21:251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tao L, Wei J, Ding XF, Ji LJ. Evaluation of the clinical efficacy and safety of TST33 mega hemorrhoidectomy for severe prolapsed hemorrhoids. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:6060-6068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chiarelli M, Guttadauro A, Maternini M, Lo Bianco G, Tagliabue F, Achilli P, Terragni S, Gabrielli F. The clinical and therapeutic approach to anal stenosis. Ann Ital Chir. 2018;89:237-241. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2089] [Cited by in RCA: 2024] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Law WL, Chu KW. Triple rubber band ligation for hemorrhoids: prospective, randomized trial of use of local anesthetic injection. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:363-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Idrees JJ, Clapp M, Brady JT, Stein SL, Reynolds HL, Steinhagen E. Evaluating the Accuracy of Hemorrhoids: Comparison Among Specialties and Symptoms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:867-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lu M, Shi GY, Wang GQ, Wu Y, Liu Y, Wen H. Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy with anal cushion suspension and partial internal sphincter resection for circumferential mixed hemorrhoids. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5011-5015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Brusciano L, Gambardella C, Terracciano G, Gualtieri G, Schiano di Visconte M, Tolone S, Del Genio G, Docimo L. Postoperative discomfort and pain in the management of hemorrhoidal disease: laser hemorrhoidoplasty, a minimal invasive treatment of symptomatic hemorrhoids. Updates Surg. 2020;72:851-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Theodoropoulos GE, Michalopoulos NV, Linardoutsos D, Flessas I, Tsamis D, Zografos G. Submucosal anoderm-preserving hemorrhoidectomy revisited: a modified technique for the surgical management of hemorrhoidal crisis. Am Surg. 2013;79:1191-1195. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Katdare MV, Ricciardi R. Anal stenosis. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:137-145, Table of Contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/