Published online Oct 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i38.111549

Revised: August 3, 2025

Accepted: September 2, 2025

Published online: October 14, 2025

Processing time: 103 Days and 22.9 Hours

Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma presents with various clinical presentations and endoscopic features. While gastric lesions are primarily assessed via endoscopic forceps biopsy, pathological confirmation of MALT lymphoma is frequently challenging, with low detection rates commonly observed.

We describe a 61-year-old male patient with gastric MALT lymphoma due to intermittent abdominal discomfort lasting over six months. The initial endoscopic forceps biopsy was suggestive of gastric lymphoma. Confirmation of the MALT lymphoma diagnosis was ultimately obtained through a jumbo biopsy specimen harvested via endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

We report a case of gastric MALT lymphoma diagnosed through ESD, high

Core Tip: Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma has various clinical presentations and endoscopic features. While gastric lesions are primarily assessed via endoscopic forceps biopsy, pathological confirmation of MALT lymphoma is frequently challenging, with low detection rates commonly observed. We report a case of gastric MALT lymphoma diagnosed through endoscopic submucosal dissection, highlighting its potential as a diagnostic tool when forceps biopsy yields negative or inconclusive results.

- Citation: Li SH, Niu WW, Huo XX, Zhang H, Shi LM, Liu YT, Xing JJ, Feng ZX, Wang N. Value of endoscopic submucosal dissection in diagnosing gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(38): 111549

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i38/111549.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i38.111549

Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, a B-cell lymphoma subtype, arises from the marginal zone within extranodal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue[1]. The incidence of MALT lymphoma comprises 7%-8% of all lymphoma diagnoses annually[2]. Compared to other types of malignant tumors, MALT lymphoma exhibits a characteristically indolent progression and is associated with significantly improved survival outcomes[3]. It primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract, although it can also affect the lungs, eyes, and skin, with the stomach being the most commonly affected site[4]. MALT lymphoma typically progresses slowly and has a favorable prognosis; however, advanced disease is detected in approximately 10% of low-grade variants[5], necessitating early diagnosis and timely treatment. Clinically, non-characteristic gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, and weight loss are commonly reported in gastric MALT lymphoma cases[6]. Rarely, MALT lymphoma can predispose patients to severe clinical events, including bleeding, obstruction, or perforation[7]. Diagnostic tools, such as positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan, bone marrow aspiration biopsy, serum protein electrophoresis, or genetic testing, provide invaluable information; however, a definitive diagnosis relies on histopathological examination, immunohistochemical staining, and molecular genetic analysis[8,9]. Endoscopic findings of MALT lymphoma widely vary among cases and include erosions, erythema, discoloration, atrophy, ulcers, and subepithelial lesions[8]. While endoscopic biopsy with forceps remains the standard for diagnosing gastric MALT lymphoma, the low sensitivity of this technique warrants alternative diagnostic strategies[10], such as endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), especially in cases where biopsy results are inconclusive.

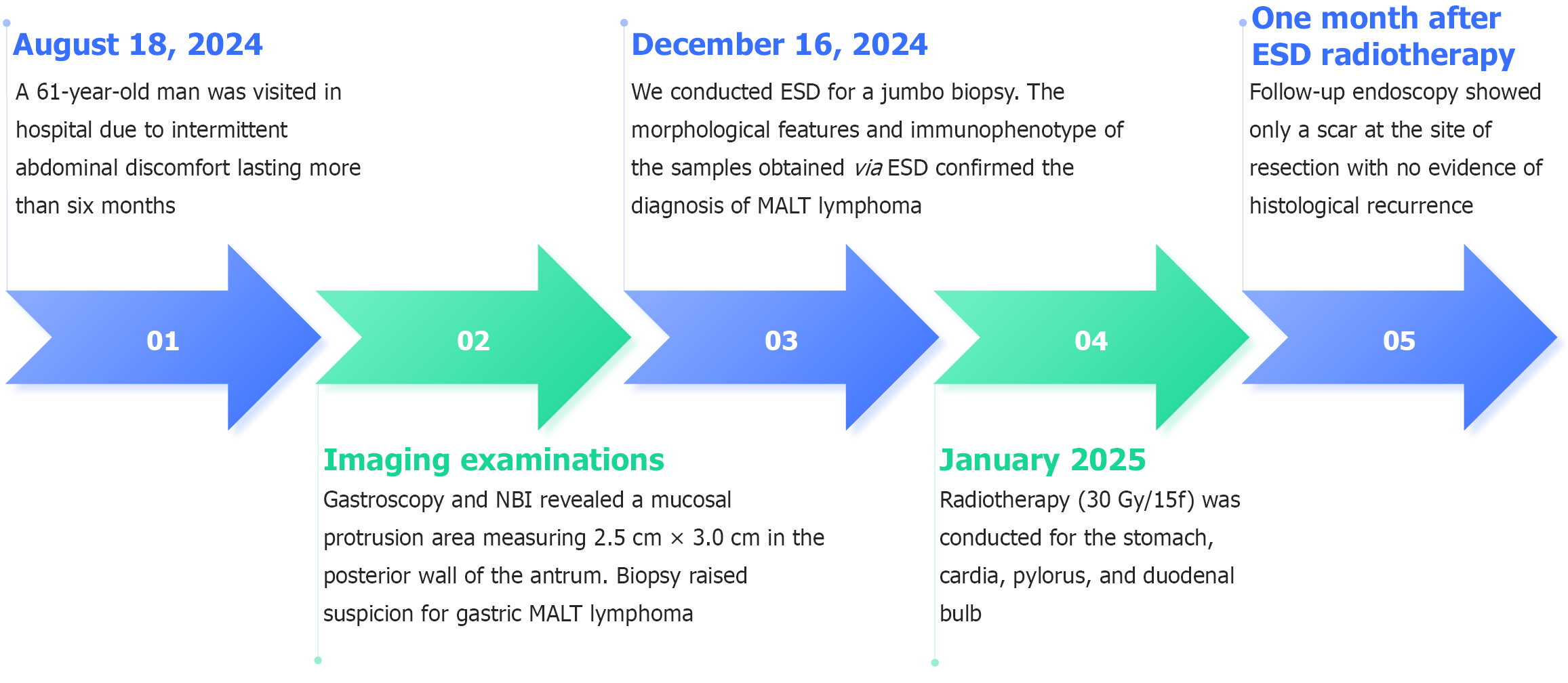

On August 18, 2024, a 61-year-old man visited in the Outpatient Department of Gastroenterology, Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University, due to intermittent abdominal discomfort lasting more than six months.

A six-month history of recurrent abdominal symptoms preceded consultation, characterized primarily by episodic dis

Past physical health.

The patient reported no familial malignancies in their medical history.

Physical examination demonstrated no clinically significant abnormalities.

The complete blood count, blood biochemical test, stool exam, occult blood test, and tumor markers were all in normal ranges. Testing for Helicobacter pylori via14C-urea breath assay yielded negative results.

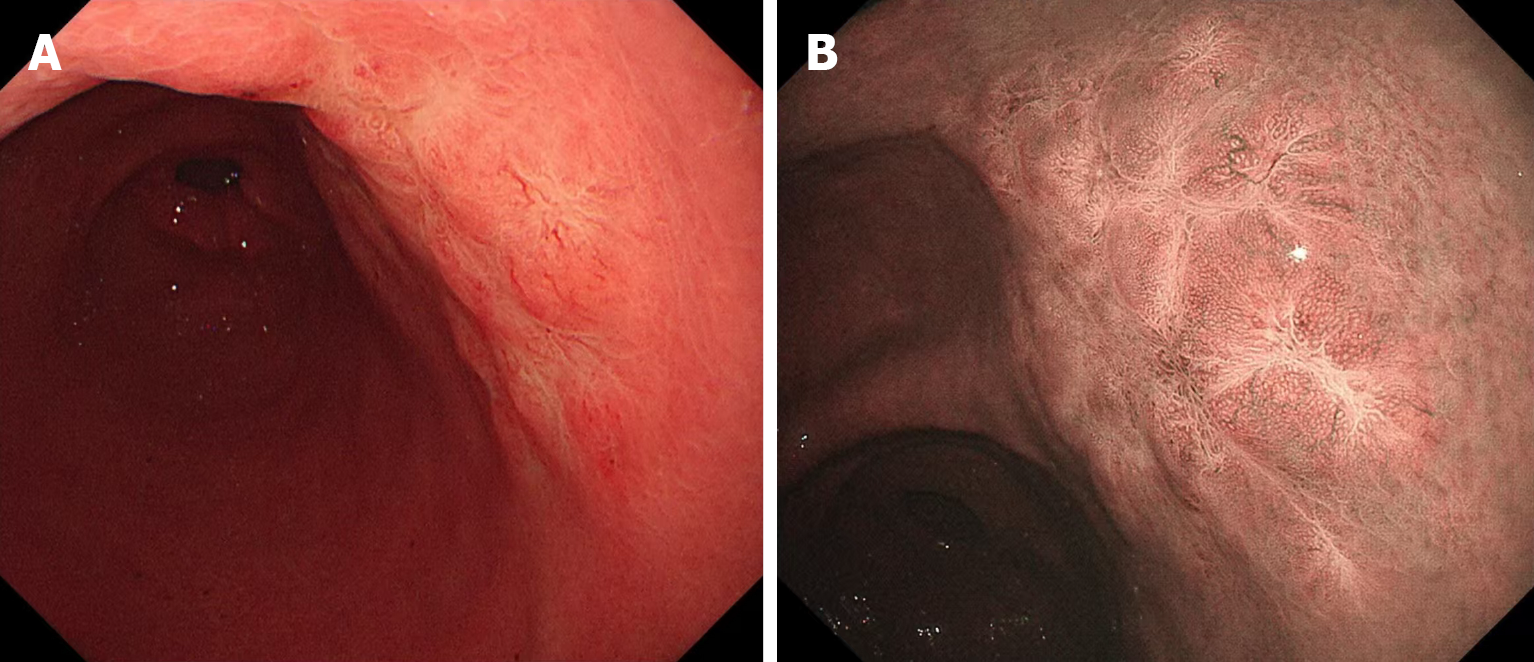

Gastroscopy and narrow band imaging revealed a mucosal protrusion area measuring 2.5 cm × 3.0 cm in the posterior wall of the antrum (Figure 1). Biopsy revealed infiltrating lymphocytes in the lamina propria with uniform morphology, raising suspicion for gastric MALT lymphoma. No evidence of hypermetabolic foci was detected on PET-CT in the stomach and other parts of the body.

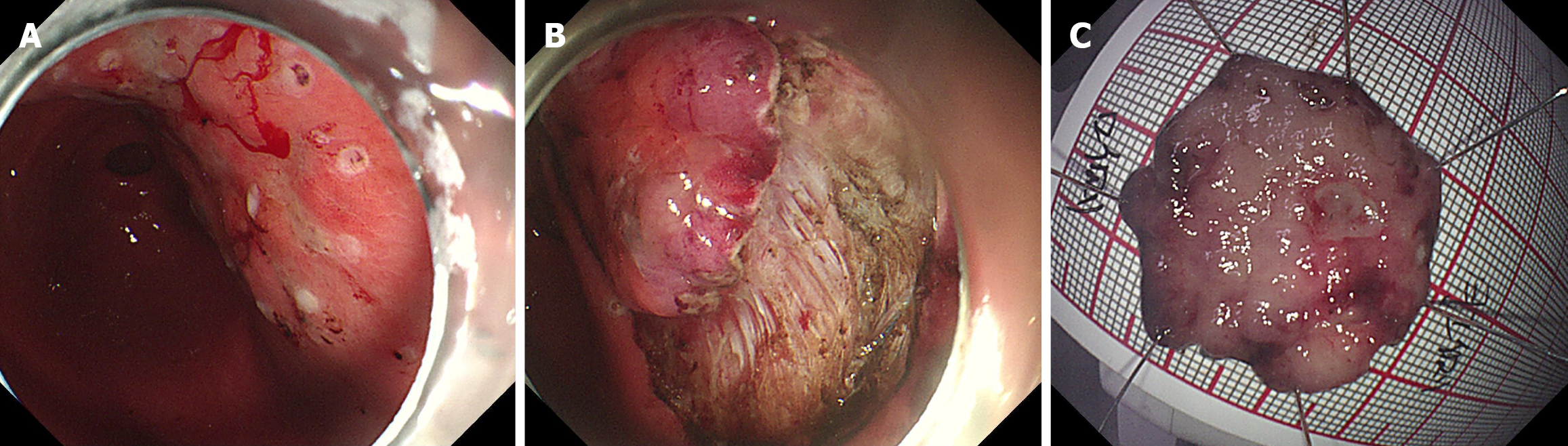

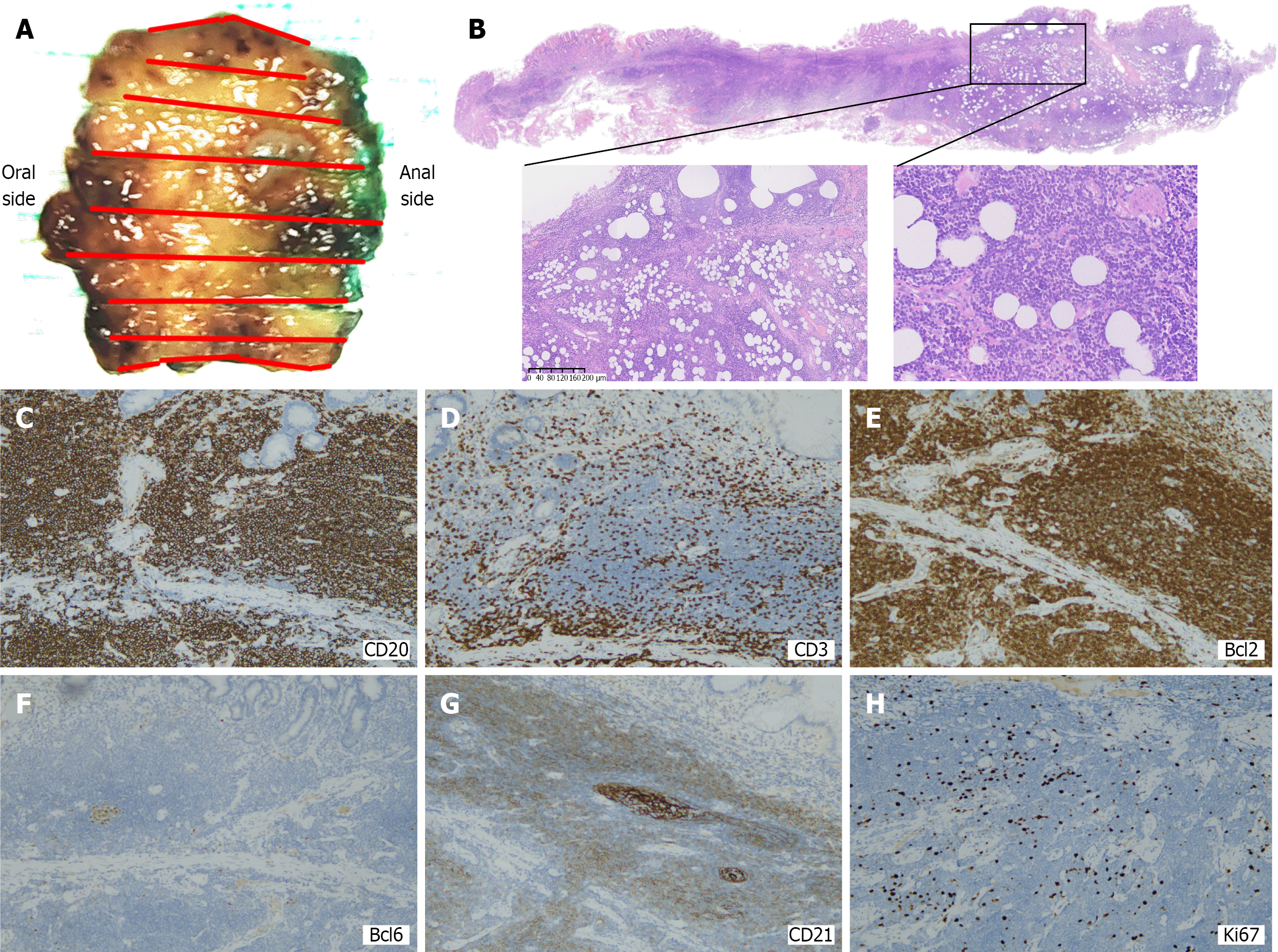

Combined with the results of gastroscopy, imaging, and pathological examination, the diagnosis of MALT was considered (Figure 2). No complications occurred due to the procedure. The morphological features and immunopheno

Gastric MALT lymphoma.

Focal positivity detected at the deep aspect of the resection specimen; therefore, radiotherapy (30 Gy/15f) was conducted for the stomach, cardia, pylorus, and duodenal bulb to improve local control, which was completed in January 2025. We also prescribed esomeprazole for the patient.

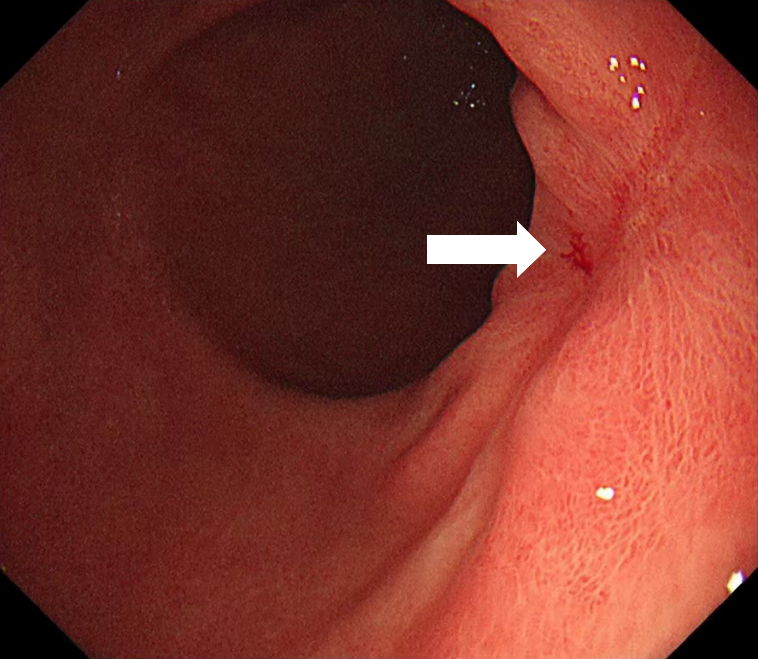

Follow-up endoscopy 4 weeks post-radiotherapy revealed mature scar tissue at the ESD site without histopathological recurrence (Figure 4). The timeline of the patient's key clinical information was shown in Figure 5.

This case represents the first instance at our center where diagnostic ESD was employed for suspected gastric MALT lymphoma. Previously, our standard diagnostic approach relied on traditional forceps biopsy, which, despite its widespread use, often resulted in inconclusive diagnoses, especially in cases with subtle mucosal changes.

Endoscopic biopsy with forceps, accompanied by histopathological examination, is a basic method for diagnosing gastric MALT lymphoma. This stems from the tumor’s deep mucosal/submucosal origin neoplastic cells proliferate without disrupting native glandular architecture, which constitutes the primary mucosal surface component targeted by superficial biopsy[11]. Given the nonspecific symptomatology, achieving diagnostic precision requires robust clinical suspicion combined with comprehensive biopsy protocols. When conventional endoscopic biopsy fails to establish a diagnosis, more invasive methods of tissue biopsies, such as ESD, may be necessary. ESD is particularly valuable for patients with inconclusive biopsy results, suspected submucosal infiltration, or other high-risk endoscopic features (e.g., submucosal tumor, multiple erosions, cobblestone mucosa, partial fold-thickening, and discoloration[8]). Although ESD is more expensive, it provides more accurate diagnoses for challenging cases, which could potentially reduce the need for further invasive procedures or surgeries, thus saving costs in the long run.

Previous studies have shown that ESD can successfully diagnose gastric MALT lymphoma[10]. A study utilized ESD for diagnostic clarification in eight biopsy-negative gastric MALT lymphoma suspects, yielding histological confirmation in five patients[12]. The absence of formal protocols for ESD application in gastric MALT lymphoma management, but this technique demonstrates high diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic value for early-stage mucosal pathologies. The Japanese Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society recommends ESD for accurate preoperative histopathological evaluation, particularly in cases where the preoperative pathological diagnosis is unclear and there is suspicion of submucosal infiltration. This approach ensures precise diagnosis and may guide treatment decisions preoperatively[13]. However, rigorous comparative studies evaluating the diagnostic sensitivity, specificity and cost-efficiency of ESD vs conventional forceps biopsy remain imperative for optimizing gastric MALT lymphoma management.

While ESD played a primary diagnostic role in this case, it also provided an opportunity for therapeutic intervention. ESD allows for tumor removal, providing not only a definitive diagnosis but also a potential curative option for localized gastric MALT lymphoma. Thus, when systemic examinations show no significant abnormalities, the lesion is considered to be in the submucosal layer, and biopsy results remain inconclusive, ESD may be considered for both diagnosis and treatment.

Although ESD offers considerable benefits in managing gastric MALT lymphoma, several procedural limitations persist. The main drawback of ESD is its invasive nature, which increases the risk of bleeding and perforation[14]. The delayed bleeding risk spans 2.6% to 8.5%, contrasted with a 2.3%-3.9% perforation probability[15]. Proton pump inhibitors therapy is recommended post-endoscopic resection to reduce ulcer-related morbidity, targeting iatrogenic injuries from the procedure[16]. ESD is generally contraindicated in patients with severe comorbidities, such as uncontrolled cardiovascular or respiratory diseases, which may complicate the procedure. Additionally, patients with high risks of bleeding or perforation, such as those with coagulopathy or a history of gastrointestinal perforations, should be excluded. For larger or more extensive gastric MALT lymphomas, ESD may not completely remove the lesion, and additional treatment methods, such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy, may be necessary. Therefore, clinicians must rigorously evaluate the patient’s comorbidities, lesion dimensions/topography, and complication risks (e.g., hemorrhage, perforation) prior to initiating ESD.

After remission, gastric MALT lymphoma may still relapse, with a long-term relapse rate of approximately 7% to 8%, and an annual relapse rate of nearly 2.2%[17,18]. Epidemiological studies indicate a six-fold increased incidence of gastric adenocarcinoma in gastric MALT lymphoma patients relative to matched population controls[19]. The lack of robust evidence regarding long-term ESD efficacy for gastric MALT lymphoma necessitates implementing standardized surveillance protocols, enabling systematic recurrence monitoring and post-therapeutic evaluation. We recommend follow-up endoscopic evaluations at 6 months and 1 year after the procedure, with additional assessments as needed based on the patient’s clinical condition. Given the heterogeneous and non-diagnostic endoscopic features of recurrent gastric MALT lymphoma[8], sufficient biopsies at multiple sites are necessary.

In conclusion, gastric MALT lymphoma does not exhibit specific clinical signs and characteristic endoscopic features. In the presence of abnormalities in endoscopic examination, gastric MALT lymphoma should be considered even when biopsy results are inconclusive. Further assessment is necessary to minimize the risk of missed or incorrect diagnoses. ESD represents a promising diagnostic and potentially therapeutic tool for gastric MALT lymphoma, particularly when biopsy results are inconclusive. Larger studies are needed to evaluate its efficacy in a broader range of patients.

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to the patient and his family for their support.

| 1. | Sagaert X, Van Cutsem E, De Hertogh G, Geboes K, Tousseyn T. Gastric MALT lymphoma: a model of chronic inflammation-induced tumor development. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:336-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Raderer M, Kiesewetter B, Ferreri AJ. Clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment of marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:153-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ma X, Qin L, Liu Y, Bian W, Sun D. Perforation caused by gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chahil N, Bloom P, Tyson J, Jazwari S, Robilotti J, Gaultieri N. Novel approach to treatment of rectal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:2969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Matysiak-Budnik T, Fabiani B, Hennequin C, Thieblemont C, Malamut G, Cadiot G, Bouché O, Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A. Gastrointestinal lymphomas: French Intergroup clinical practice recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up (SNFGE, FFCD, GERCOR, UNICANCER, SFCD, SFED, SFRO, SFH). Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zucca E, Copie-Bergman C, Ricardi U, Thieblemont C, Raderer M, Ladetto M; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Gastric marginal zone lymphoma of MALT type: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24 Suppl 6:vi144-vi148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Min GJ, Kang D, Lee HH, Kim SJ, Kim TY, Jeon YW, O JH, Choi BO, Park G, Cho SG. Long-term clinical outcomes of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma in real-world experience. Ann Hematol. 2023;102:877-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Park BS, Lee SH. Endoscopic features aiding the diagnosis of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Yeungnam Univ J Med. 2019;36:85-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gong EJ, Choi KD. [Diagnosis and Treatment of Gastric Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2019;74:304-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim GH, Choi BG, Lee JN, Park SH, Lee BE, Ryu DY, Song GA, Park DY. [2 cases of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma presenting as a submucosal tumor-like lesion]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;56:103-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Fischbach W, Aleman BM, Boot H, Du MQ, Megraud F, Montalban C, Raderer M, Savio A, Wotherspoon A; EGILS group. EGILS consensus report. Gastric extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT. Gut. 2011;60:747-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Suekane H, Iida M, Kuwano Y, Kohrogi N, Yao T, Iwashita A, Fujishima M. Diagnosis of primary early gastric lymphoma. Usefulness of endoscopic mucosal resection for histologic evaluation. Cancer. 1993;71:1207-1213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Uedo N, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Fujimoto K. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer (second edition). Dig Endosc. 2021;33:4-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 72.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Kim GH. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: It is time to consider the quality of its outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:5800-5803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Uozumi T, Abe S, Makiguchi ME, Nonaka S, Suzuki H, Yoshinaga S, Saito Y. Complications of endoscopic resection in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Clin Endosc. 2023;56:409-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Park CH, Yang DH, Kim JW, Kim JH, Kim JH, Min YW, Lee SH, Bae JH, Chung H, Choi KD, Park JC, Lee H, Kwak MS, Kim B, Lee HJ, Lee HS, Choi M, Park DA, Lee JY, Byeon JS, Park CG, Cho JY, Lee ST, Chun HJ. Clinical Practice Guideline for Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastrointestinal Cancer. Clin Endosc. 2020;53:142-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 17. | Zullo A, Hassan C, Cristofari F, Andriani A, De Francesco V, Ierardi E, Tomao S, Stolte M, Morini S, Vaira D. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on early stage gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:105-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Choi YJ, Lee DH, Kim JY, Kwon JE, Kim JY, Jo HJ, Shin CM, Kim HY, Park YS, Kim N, Jung HC, Song IS. Low Grade Gastric Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma: Clinicopathological Factors Associated with Helicobacter pylori Eradication and Tumor Regression. Clin Endosc. 2011;44:101-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Capelle LG, de Vries AC, Looman CW, Casparie MK, Boot H, Meijer GA, Kuipers EJ. Gastric MALT lymphoma: epidemiology and high adenocarcinoma risk in a nation-wide study. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2470-2476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/