Published online Jan 28, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i4.504

Peer-review started: November 29, 2017

First decision: December 13, 2017

Revised: January 1, 2018

Accepted: January 1, 2018

Article in press: January 1, 2018

Published online: January 28, 2018

Processing time: 58 Days and 0.9 Hours

To evaluate the safety and feasibility of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) for total laparoscopic uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy.

The clinical data of 42 patients who were divided into an ERAS group (n = 20) and a control group (n = 22) were collected. The observed indicators included operation conditions, postoperative clinical indexes, and postoperative serum stress indexes. Measurement data following a normal distribution are presented as mean ± SD and were analyzed by t-test. Count data were analyzed by χ2 test.

The operative time, volume of intraoperative blood loss, and number of patients with conversion to open surgery were not significantly different between the two groups. Postoperative clinical indexes, including the time to initial anal exhaust, time to initial liquid diet intake, time to out-of-bed activity, and duration of hospital stay of patients without complications, were significantly different between the two groups (t = 2.045, 8.685, 2.580, and 4.650, respectively, P < 0.05 for all). However, the time to initial defecation, time to abdominal drainage-tube removal, and the early postoperative complications were not significantly different between the two groups. Regarding postoperative complications, on the first and third days after the operation, the white blood cell count (WBC) and C reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels in the ERAS group were significantly lower than those in the control group.

The perioperative ERAS program for total laparoscopic uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy is safe and effective and should be popularized. Additionally, this program can also reduce the duration of hospital stay and improve the degree of comfort and satisfaction of patients.

Core tip: For gastric cancer, uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy is still the most important treatment. However, the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol for the safety of gastric surgery is not clear. Therefore, we conducted a long-term follow-up and observation with a large sample. Our study demonstrated that the use of the perioperative ERAS program for total laparoscopic uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy is safe and effective and should be popularized.

- Citation: Zang YF, Li FZ, Ji ZP, Ding YL. Application value of enhanced recovery after surgery for total laparoscopic uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(4): 504-510

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i4/504.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i4.504

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) is a concept promoted by some countries in Europe and America in recent years[1,2]. It can shorten the hospitalization time and improve the recovery rate after surgery[3]. This concept has been used by surgical centers in Europe and America for herniorrhaphy[4], gastrointestinal surgery[5,6], gynecologic operations[7], and other applications. The ERAS concept emphasizes the reduction of postoperative stress and trauma to the patient due to the surgery during the perioperative period, thereby promoting the rehabilitation of patients[8].

The uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy closure of the proximal jejunum without interruption is based on Billroth II + Braun anastomosis. It was first reported by Van Stiegmann et al[9] in 1988. Then, Uyama et al[10], in 2005, and Ahn et al[11], in 2014, reported laparoscopic-assisted and single-incision laparoscopic non-interrupted Roux-en-Y anastomoses. The incidence of Roux stasis syndrome (RSS) is 10%-30% after traditional Roux-en-Y anastomosis[12,13]. The advantages of the uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy during digestive tract reconstruction include a reduction of the steps involved in freeing the jejunum during the operation, reduced mesangial damage and interference, retention of nerves and normal pacemakers, and significantly reduced occurrence of RSS. Thus, for obese patients or those with short-term mesothelioma, the procedure is particularly applicable[14,15].

This study evaluated the safety and feasibility of ERAS in the uncut operation.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Shandong University. Patients or their families signed informed consent forms.

A total of 42 consecutive patients undergoing total laparoscopic uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy (uncut operation) from July 2015 to November 2016 at the Second Hospital of Shandong University in China were included in this study. The data were analyzed in a retrospective cohort study. The patients were randomly divided into an ERAS group and a control group. No significant difference was found between the two groups in sex, age, body mass index, or operation method (Table 1) (P > 0.05). Throughout the study period, the same group of surgeons treated all patients and were responsible for all procedures, including the surgical techniques as well as the choice of surgical instruments.

| Clinical information | ERAS group (n = 20) | Control group (n = 22) | Statistics | P value |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 71.5 ± 8.1 | 72.9 ± 6.7 | t = 0.613 | > 0.05 |

| Sex (male/female) | 14/6 | 17/5 | χ2 = 0.287 | > 0.05 |

| Body mass index, (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 23.6 ± 3.4 | 22.8 ± 4.6 | t = 0.636 | > 0.05 |

The inclusion criteria were: (1) Age ≥ 18 yr old; (2) Patients who preferred to undergo uncut surgery; (3) Gastrointestinal biopsy and CT examination confirmed gastric malignant tumors before the operation. The clinical stage was assessed by CT examination and found to be T1-3N1-3M0 (7th edition of the UICC-AJCC TNM classification of gastric cancer); and (4) No significant swollen fusion of metastatic lymph nodes was present. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients who refused to participate in the study; (2) Patients who had serious underlying diseases; (3) Patients with distant metastases or unresectable tumors; (4) Patients who had serious complications and could not continue to undergo the ERAS procedure; (5) Patients who had a history of other major abdominal surgeries; and (6) Patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy before surgery.

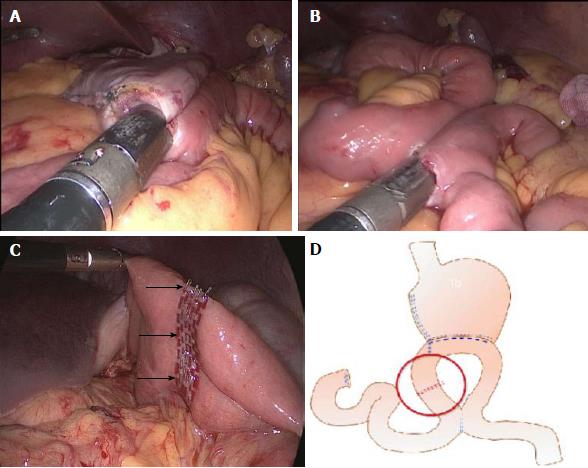

Patients in the ERAS group underwent a series of perioperative treatment regimens. The control group underwent a conventional perioperative treatment protocol (Table 2). After routine resection of the D2 group lymph nodes, the duodenum was cut 2 cm from the pylorus, and the stomach was cut 5 cm from the upper edge of the tumor. Then, a side-to-side gastrojejunostomy was performed on the jejunum, which was approximately 20 cm from the ligament of Treitz and the residual stomach (Figure 1A). Approximately 10 cm to 30 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz, a side-to-side jejunojejunostomy via a Braun anastomosis was performed to divert the duodenal fluid (Figure 1B). The jejunal occlusion site (uncut reconstruction) was approximately 3 cm from the jejunum (Figure 1C). A schematic diagram of the uncut reconstruction is shown in Figure 1D.

| Perioperative treatment program | ERAS Group | Control group |

| Preoperative | ||

| Preparation | ERAS-related health education to alleviate tension in patients performed by both surgeons and anesthesiologists. The definition of the visual analog scale was explained to patients. | Regular preoperative education and preoperative conversation only with surgeons, and the definition of the visual analogue scale was explained to patients. |

| Diet | Patients drank 1000 mL of a 10% glucose solution 10 h before surgery and 500 mL of the 10% glucose solution 2 h before surgery. | Fasting for 12 h before surgery No drinking for 6 h before surgery |

| Bowel preparation | None | The bowel was cleaned twice the day before surgery and the day of surgery. |

| Intraoperative | ||

| Nasogastric tube | Not used | Removed after exhaust |

| Body temperature | Intraoperative warm-air body heating | None |

| Urinary catheter | Removed after waking from anesthesia | 1 d after surgery |

| Postoperative | ||

| Anesthesia and analgesics | Local anesthesia at surgical incision + PCIA + NSAIDs | PCIA |

| Diet | Patients chewed gum after waking from anesthesia, drank water 6 h after surgery, and were encouraged to remain on a liquid diet until return to a normal diet. | Patients drank water after anal exhaust and gradually returned to a normal diet. |

| Activity | Patients were encouraged to get out of bed for more than 6 h a day and walk the length of the ward. | Decided by patients |

Observation indicators included: (1) Operation conditions, including operative time, blood loss, and conversion to open surgery; (2) Postoperative clinical indexes, including time to initial anal exhaust, time to initial liquid diet intake, time to out-of-bed activity, time to initial defecation, time to abdominal drainage tube removal, duration of hospital stay of patients without complications, early postoperative complications, and visual analogue scale scores on the first and third days after the operation; and (3) Postoperative serum stress indexes, including detection of the white blood cell count (WBC) and C reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels at 1 d and 3 d after the operation.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 19.0. Measurement data following a normal distribution are presented as mean ± SD and were analyzed by t-test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The operative time (t = 0.422), volume of intraoperative blood loss (t = 2.006), and number of patients with conversion to open surgery (χ2 = 0.01) were not significantly different between the two groups (P > 0.05 for all), which indicated that the ERAS program did not affect the surgical results, as illustrated in Table 3.

| Operation parameter | ERAS group (n = 20) | Control group (n = 22) | Statistics | P value |

| Operative time (min, mean ± SD) | 217.9 ± 52.5 | 225.4 ± 61.7 | t = 0.422 | > 0.05 |

| Volume of intraoperative blood loss (mL, mean ± SD) | 166.1 ± 12.5 | 150.9 ± 31.7 | χ2 = 2.006 | > 0.05 |

| Open surgery | 2 | 1 | t = 0.01 | > 0.05 |

The time to initial anal exhaust, time to initial liquid diet intake, time to out-of-bed activity, duration of hospital stay of patients without complications, and visual analog scale score on the first and third days after the operation were 2.9 ± 1.1 d, 1.6 ± 0.7 d, 2.3 ± 0.8 d, 7.5 ± 1.6 d, 4.0 ± 1.4, and 3.5 ± 1.8, respectively, in the ERAS group and 3.7 ± 1.4 d, 4.1 ± 1.1 d, 4.2 ± 3.2 d, 10.2 ± 2.1 d, 5.4 ± 1.6, and 4.8 ± 1.5 in the control group, respectively, resulting in statistically significant differences between the two groups (t = 2.045, 8.685, 2.580, 4.650, 2.361, and 2.551, respectively; P < 0.05 for all). However, the time to initial defecation, time to abdominal drainage-tube removal, and the early postoperative complications were not significantly different between the two groups.

The rates of anastomotic leakage, postoperative ileus, pneumonia, cardiac disorders, and overall complications did not significantly differ between the two groups, which indicated the safety of the procedure. In addition, the perioperative ERAS program effectively reduced the pain and hospitalization time of patients. Overall compliance with ERAS protocols was good, as illustrated in Table 4.

| Index | ERAS group (n = 20) | Control group (n = 22) | Statistics | P value |

| Time to initial anal exhaust (d, mean ± SD) | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 1.4 | t = 2.045 | < 0.05 |

| Time to initial liquid diet intake (d, mean ± SD) | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 4.1 ± 1.1 | t = 8.685 | < 0.05 |

| Time to out-of-bed activity (d, mean ± SD) | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 4.2 ± 3.2 | = 2.580 | < 0.05 |

| Time to initial defecation (d, mean ± SD) | 4.2 ± 1.7 | 4.9 ± 2.0 | t = 1.216 | > 0.05 |

| Time to abdominal drainage tube removal (d, mean ± SD) | 7.3 ± 2.6 | 8.7 ± 3.2 | t = 1.546 | > 0.05 |

| Duration of hospital stay of patients without complications (d, mean ± SD) | 7.5 ± 1.6 | 10.2 ± 2.1 | t = 4.650 | < 0.05 |

| Early postoperative complications | 1 | 1 | χ2 = 0.430 | > 0.05 |

| VAS POD1 (points, mean ± SD) | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 5.4 ± 1.6 | = 2.361 | < 0.05 |

| VAS POD3 (points, mean ± SD) | 3.5 ± 1.8 | 4.8 ± 1.5 | = 2.551 | < 0.05 |

Postoperative serum stress indexes are summarized in Table 5. On the first and third days after the operation, the WBC and CRP and IL-6 levels in the ERAS group were significantly lower than those in the control group, which suggested that the ERAS program significantly reduced the postoperative stress responses.

| Stress index (mean ± SD) | ERAS group (n = 20) | Control group (n = 22) | Statistics | P value |

| WBC POD1 (× 109/L) | 12.7 ± 3.1 | 15.2 ± 4.2 | t = 2.176 | < 0.05 |

| WBC POD3 (× 109/L) | 9.5 ± 2.6 | 12.4 ± 3.3 | t = 3.141 | < 0.05 |

| CRP POD1 (mg/dL) | 7.5 ± 2.9 | 11.2 ± 3.4 | = 3.775 | < 0.05 |

| CRP POD3 (mg/dL) | 5.3 ± 3.1 | 7.3 ± 2.8 | = 2.197 | < 0.05 |

| IL-6 PDO1 (pg/dL) | 55.2 ± 21.9 | 85.7 ± 35.6 | t = 3.303 | < 0.05 |

| IL-6 POD3 (pg/dL) | 20.3 ± 5.7 | 24.1 ± 6.2 | t = 2.061 | < 0.05 |

Currently, it is unclear whether the introduction of the ERAS concept benefits the Chinese population. Gastrectomy involving the reconstruction of the digestive tract is extremely specialized, and the application of ERAS after gastrectomy is uncommon. In the present study, the ERAS protocol was novel for gastric surgery[16]. However, the ERAS concept advocates giving patients adequate preoperative preparation (good preoperative communication, nutritional treatment, and comfortable gastrointestinal preparation) to reduce preoperative stress[17,18] The use of warming, planned rehydration, and increased postoperative analgesia after surgery reduces postoperative traumatic stress responses[16]. The ERAS concept emphasizes that patients get out of bed, ingest a liquid diet, and undergo removal of the gastrointestinal decompression tube and catheter earlier to promote postoperative intestinal function recovery and accelerated rehabilitation[19,20]. In the present study, we demonstrated that the ERAS concept can be applied for gastric cancer treatment. This concept can help achieve faster patient recovery without increasing postoperative morbidity.

Surgical treatment of gastric cancer consists of two important parts. The first part is tumor resection. At present, the use of D2 radical surgery has achieved consensus in the field. The second part is the reconstruction of the digestive tract. Due to the development of chemotherapy and targeted drugs, the survival of patients with gastric cancer has significantly improved[21,22]. The uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy does not involve cutting the jejunum, which reduces the time needed for dissociation of the jejunum. Therefore, the blood supply of the jejunum remains intact, which reduces intraoperative bleeding and ensures that the function of the intestinal wall nerve is not damaged[12,13]. Simultaneously, this technique can reduce the incidence of RSS[23,24]. Scholars worldwide have applied the coincidence method to endoscopic assisted gastrointestinal reconstruction and total laparoscopic digestive reconstruction and confirmed its safety and effectiveness[10,25]. Uncut surgery in conjunction with the ERAS concept can achieve early recovery in patients.

In this study, the perioperative administration of the ERAS concept showed obvious advantages when intraoperative parameters, postoperative clinical indicators, and postoperative stress responses were compared. The ERAS concept of perioperative treatment significantly shortened the hospital stay after surgery (approximately 2.7 d), significantly improved patient comfort during the perioperative period, and reduced pain without increasing the operating time and blood loss during surgery. The time to initial liquid diet intake, time to out-of-bed activity, and time to postoperative gastrointestinal function recovery were significantly shorter than those in the control group under the premise of the same recovery effect[26,27]. Additionally, the ERAS concept can effectively reduce the level of postoperative stress in patients. However, some reports have suggested that a delayed return to a normal diet can reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal anastomotic fistula[28]. However, most patients in the study were able to tolerate early postprandial feeding. A large-sample, multicenter, randomized controlled study confirmed the safety for patients with upper gastrointestinal tract surgery to begin a normal diet early. Further research regarding whether the ERAS concept has potential benefits for other patients is necessary. The above results show that health education, the development of a detailed diet, and encouraging patients to eat as soon as possible can effectively promote recovery and shorten hospital stay.

In conclusion, through the optimization and improvement of the traditional perioperative treatment program in this study, our results suggest that the use of the perioperative ERAS program for total laparoscopic uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy is safe and effective and should be popularized. This program can also reduce the duration of the hospital stay and improve the degree of comfort and satisfaction of patients.

For gastric cancer, uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy is still the most important treatment. However, the safety of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol for gastric surgery is not clear.

Only a few studies have focused on the use of the perioperative ERAS program for total laparoscopic uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy. It is unclear whether introduction of the ERAS concept benefits the Chinese population.

This study aimed to evaluate the safety and feasibility of ERAS for total laparoscopic uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy. We can use the ERAS protocol for these patients to reduce the duration of the hospital stay and improve the degree of comfort and satisfaction of patients.

The clinical data of 42 patients who were divided into a control group of 22 patients and an ERAS group of 20 patients were collected. The observed indicators included operation conditions, postoperative clinical indexes, and postoperative serum stress indexes. Measurement data following a normal distribution are presented as mean ± SD and were analyzed by t-test. Count data were analyzed by chi-squared test.

The operative time, volume of intraoperative blood loss, and number of patients with conversion to open surgery were not significantly different between the two groups. Postoperative clinical indexes, including the time to initial anal exhaust, time to initial liquid diet intake, time to out-of-bed activity, and duration of hospital stay of patients without complications, were significantly different between the two groups. However, the time to initial defecation, time to abdominal drainage-tube removal, and the early postoperative complications were not significantly different between the two groups. Regarding postoperative complications, on the first and the third days after the operation, the white blood cell count and C reactive protein and interleukin-6 levels in the ERAS group were significantly lower than those in the control group.

We found that the perioperative ERAS program for total laparoscopic uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy is safe and effective and should be popularized. In this study, we carried out long-term follow-up and prognosis analysis of patients with gastric cancer who received uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy at our center to provide a theoretical basis for prognosis improvement of the patients.

From this study, we can find that ERAS can be used not only for herniorrhaphy, gastrointestinal surgery, gynecologic operations, and other applications, but also for gastric surgery. The direction of the future research is that an effective perioperative management program specific for gastric cancer is needed to be developed. The best method is to conduct a large-scale clinical trial to verify it.

| 1. | Fearon KC, Ljungqvist O, Von Meyenfeldt M, Revhaug A, Dejong CH, Lassen K, Nygren J, Hausel J, Soop M, Andersen J. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a consensus review of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clin Nutr. 2005;24:466-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1001] [Cited by in RCA: 1058] [Article Influence: 50.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Bona S, Molteni M, Rosati R, Elmore U, Bagnoli P, Monzani R, Caravaca M, Montorsi M. Introducing an enhanced recovery after surgery program in colorectal surgery: a single center experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17578-17587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gravante G, Elmussareh M. Enhanced recovery for non-colorectal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:205-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Callesen T, Bech K, Kehlet H. One-thousand consecutive inguinal hernia repairs under unmonitored local anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1373-1376, table of contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Delaney CP, Fazio VW, Senagore AJ, Robinson B, Halverson AL, Remzi FH. ‘Fast track’ postoperative management protocol for patients with high co-morbidity undergoing complex abdominal and pelvic colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1533-1538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schwenk W, Neudecker J, Raue W, Haase O, Müller JM. “Fast-track” rehabilitation after rectal cancer resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:547-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Recart A, Duchene D, White PF, Thomas T, Johnson DB, Cadeddu JA. Efficacy and safety of fast-track recovery strategy for patients undergoing laparoscopic nephrectomy. J Endourol. 2005;19:1165-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mariani P, Slim K. Enhanced recovery after gastro-intestinal surgery: The scientific background. J Visc Surg. 2016;153:S19-S25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Van Stiegmann G, Goff JS. An alternative to Roux-en-Y for treatment of bile reflux gastritis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1988;166:69-70. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Uyama I, Sakurai Y, Komori Y, Nakamura Y, Syoji M, Tonomura S, Yoshida I, Masui T, Inaba K, Ochiai M. Laparoscopy-assisted uncut Roux-en-Y operation after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2005;8:253-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Ahn SH, Son SY, Lee CM, Jung DH, Park do J, Kim HH. Intracorporeal uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy reconstruction in pure single-incision laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: unaided stapling closure. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:e17-e21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tu BL, Kelly KA. Surgical treatment of Roux stasis syndrome. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:613-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pan Y, Li Q, Wang DC, Wang JC, Liang H, Liu JZ, Cui QH, Sun T, Zhang RP, Kong DL. Beneficial effects of jejunal continuity and duodenal food passage after total gastrectomy: a retrospective study of 704 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:17-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Park JY, Kim YJ. Uncut Roux-en-Y Reconstruction after Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy Can Be a Favorable Method in Terms of Gastritis, Bile Reflux, and Gastric Residue. J Gastric Cancer. 2014;14:229-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Morton JM, Lucktong TA, Trasti S, Farrell TM. Bovine pericardium buttress limits recanalization of the uncut Roux-en-Y in a porcine model. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:127-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yamada T, Hayashi T, Cho H, Yoshikawa T, Taniguchi H, Fukushima R, Tsuburaya A. Usefulness of enhanced recovery after surgery protocol as compared with conventional perioperative care in gastric surgery. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:34-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Stowers MD, Lemanu DP, Hill AG. Health economics in Enhanced Recovery After Surgery programs. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62:219-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Song JX, Tu XH, Wang B, Lin C, Zhang ZZ, Lin LY, Wang L. “Fast track” rehabilitation after gastric cancer resection: experience with 80 consecutive cases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nanavati AJ. Fast Track Surgery in the Elderly: Avoid or Proceed with Caution? J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:2292-2293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Williamsson C, Karlsson N, Sturesson C, Lindell G, Andersson R, Tingstedt B. Impact of a fast-track surgery programme for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2015;102:1133-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sasako M, Sakuramoto S, Katai H, Kinoshita T, Furukawa H, Yamaguchi T, Nashimoto A, Fujii M, Nakajima T, Ohashi Y. Five-year outcomes of a randomized phase III trial comparing adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 versus surgery alone in stage II or III gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4387-4393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 869] [Cited by in RCA: 1119] [Article Influence: 74.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, Lordick F, Ohtsu A, Omuro Y, Satoh T. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5823] [Cited by in RCA: 5528] [Article Influence: 345.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 23. | Miedema BW, Kelly KA. The Roux stasis syndrome. Treatment by pacing and prevention by use of an ‘uncut’ Roux limb. Arch Surg. 1992;127:295-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fan KX, Xu ZF, Wang MR, Li DT, Yang XS, Guo J. Outcomes for jejunal interposition reconstruction compared with Roux-en-Y anastomosis: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3093-3099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kim JJ, Song KY, Chin HM, Kim W, Jeon HM, Park CH, Park SM. Totally laparoscopic gastrectomy with various types of intracorporeal anastomosis using laparoscopic linear staplers: preliminary experience. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:436-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lassen K, Kjaeve J, Fetveit T, Tranø G, Sigurdsson HK, Horn A, Revhaug A. Allowing normal food at will after major upper gastrointestinal surgery does not increase morbidity: a randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2008;247:721-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Yermilov I, Jain S, Sekeris E, Bentrem DJ, Hines OJ, Reber HA, Ko CY, Tomlinson JS. Utilization of parenteral nutrition following pancreaticoduodenectomy: is routine jejunostomy tube placement warranted? Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1582-1588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tatsuishi W, Kohri T, Kodera K, Asano R, Kataoka G, Kubota S, Nakano K. Usefulness of an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol for perioperative management following open repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Surg Today. 2012;42:1195-1200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Emi M, Hanaoka N, Shin T S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma YJ