Published online Jul 14, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i26.2878

Peer-review started: March 17, 2018

First decision: April 18, 2018

Revised: May 2, 2018

Accepted: June 9, 2018

Article in press: June 9, 2018

Published online: July 14, 2018

Processing time: 118 Days and 11.9 Hours

To evaluate the clinical outcomes of patients who underwent endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection (ESTD) for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and precancerous lesions.

ESTD was performed in 289 patients. The clinical outcomes of the patients and pathological features of the lesions were retrospectively reviewed.

A total of 311 lesions were included in the analysis. The en bloc rate, complete resection rate, and curative resection rate were 99.04%, 81.28%, and 78.46%, respectively. The ESTD procedure time was 102.4 ± 35.1 min, the mean hospitalization time was 10.3 ± 2.8 d, and the average expenditure was 3766.5 ± 846.5 dollars. The intraoperative bleeding rate was 6.43%, the postoperative bleeding rate was 1.61%, the perforation rate was 1.93%, and the postoperative infection rate was 9.65%. Esophageal stricture and positive margin were severe adverse events, with an incidence rate of 14.79% and 15.76%, respectively. No tumor recurrence occurred during the follow-up period.

ESTD for ESCC and precancerous lesions is feasible and relatively safe, but for large mucosal lesions, the rate of esophageal stricture and positive margin is high.

Core tip: Endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection (ESTD) is a modified technique based on endoscopic submucosal dissection. In this paper, we found ESTD is feasible and relatively safe for treating esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and precancerous lesions. The en bloc rate was high, while the adverse event rate was relatively low. When treating large mucosal lesions, ESTD has a high rate of esophageal stricture and positive margin, which requires further treatment. Furthermore, we found that the pathology of preoperative biopsies had to be upgraded after ESTD, which suggests that the accuracy of biopsy to diagnose ESCC should be reconsidered.

- Citation: Wang J, Zhu XN, Zhu LL, Chen W, Ma YH, Gan T, Yang JL. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and precancerous lesions. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(26): 2878-2885

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i26/2878.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i26.2878

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is becoming the standard treatment for early gastrointestinal cancers, as it has a higher en bloc resection rate and a lower recurrence rate than endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)[1,2] and it can be used to resect lesions with a diameter greater than 2 cm[3]. However, esophageal ESD faces many difficulties because of the narrow esophageal lumen and thin walls[4-6]. When using conventional ESD treatment for large mucosal lesions, and especially for lesions with a circumference that exceeds three fourths of the esophageal lumen, multiple submucosal injections are required, which could prolong the procedure time and thereby increase the risk of complications[5]. Even worse, with the resected mucosa blocked in the lumen, the endoscopic view becomes unclear and may increase the difficulty of complete resection[6]. To overcome these difficulties, some modified ESD techniques have been introduced, such as the line traction method[6], the clip traction method[7], and the thread-traction method[8]; however, none of these methods was suitable for extensive application.

In 2009, Linghu et al[9] used a “submucosal tunnel” to resect successfully a circumferential esophageal mucosal lesion, which was subsequently termed an endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection (ESTD)[5]. Compared with conventional ESD, ESTD has many technical advantages, as it resects the mucosal lesions by creating a submucosal tunnel between the mucosal layer and muscular layer, after which therapeutic endoscopy can enter the tunnel and acquire a clear operative view. Moreover, the CO2 injected in the operation can help the blunt dissection of the mucosal layer, thereby reducing the number of submucosal injections, shortening the procedure time, increasing the resection speed, and reducing the injury of the muscular layer[10-12]. This approach can also incise the submucosa more completely, thereby reducing the risk of tumor metastasis and recurrence, as shown in our previous study[13]. However, there are no studies that have verified the feasibility of ESTD in superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and precancerous lesions in a large sample. The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy and safety of ESTD in treating superficial ESCC and precancerous lesions in a relatively large sample.

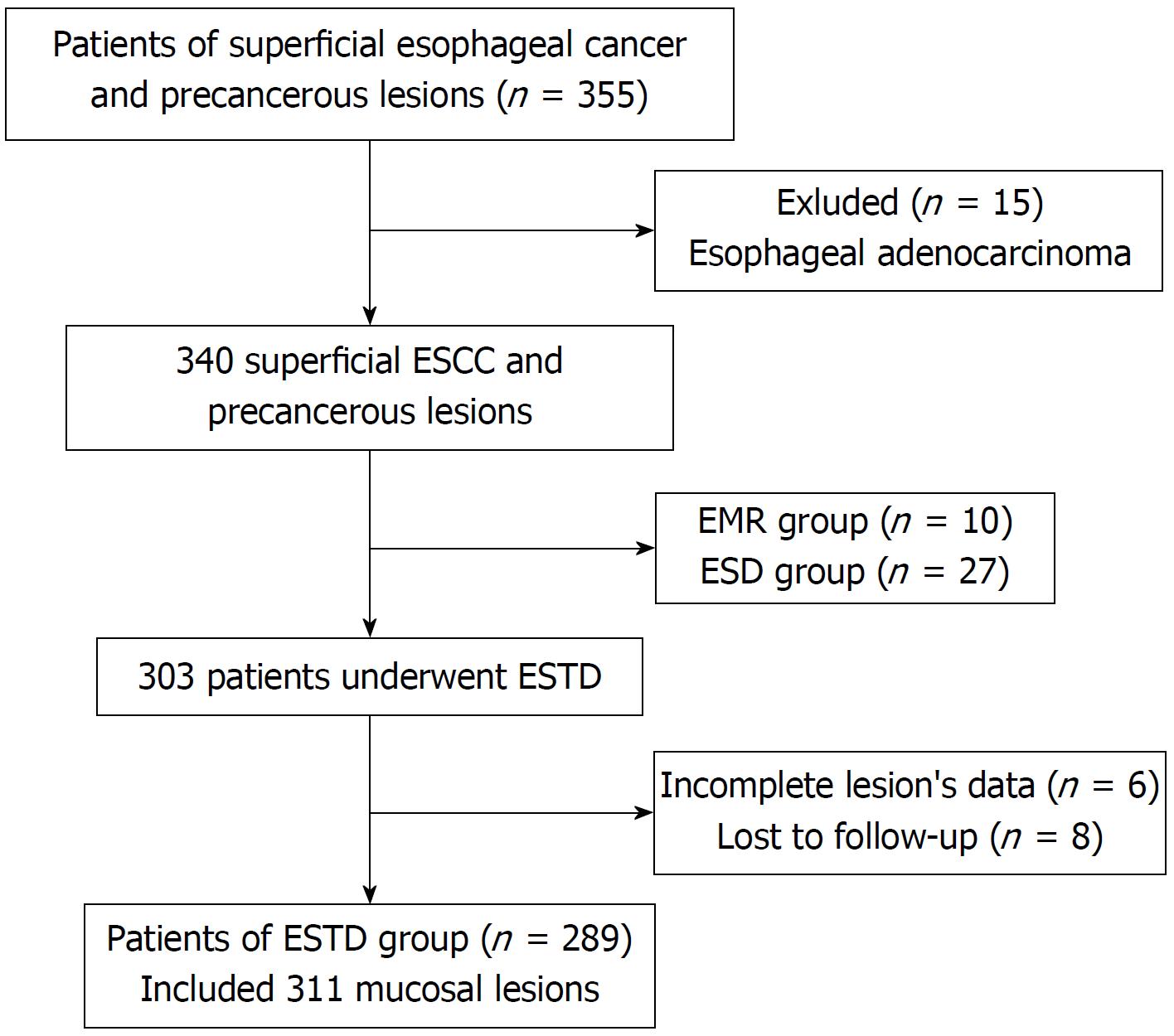

A prospectively collected endoscopic therapy database was analyzed retrospectively. All of the patients with superficial ESCC and precancerous lesions who underwent ESTD in the Digestive Endoscopy Center of West China Hospital from March 1, 2013 to May 1, 2017 were enrolled. A total of 355 patients with superficial esophageal cancer underwent endoscopic treatment. We excluded patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma, EMR/ESD procedure, and incomplete clinical data. Finally, 289 patients with 311 lesions were analyzed (Figure 1). All of the lesions were confirmed by pathological evaluation from biopsy specimens according to the Japanese classification of ESCC[14] before ESTD procedure. The clinical records and ESTD records were collected, and demographic and endoscopic characteristics were retrospectively reviewed. The endoscopic type of lesion was assessed according to the Paris endoscopic classification[15]. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University.

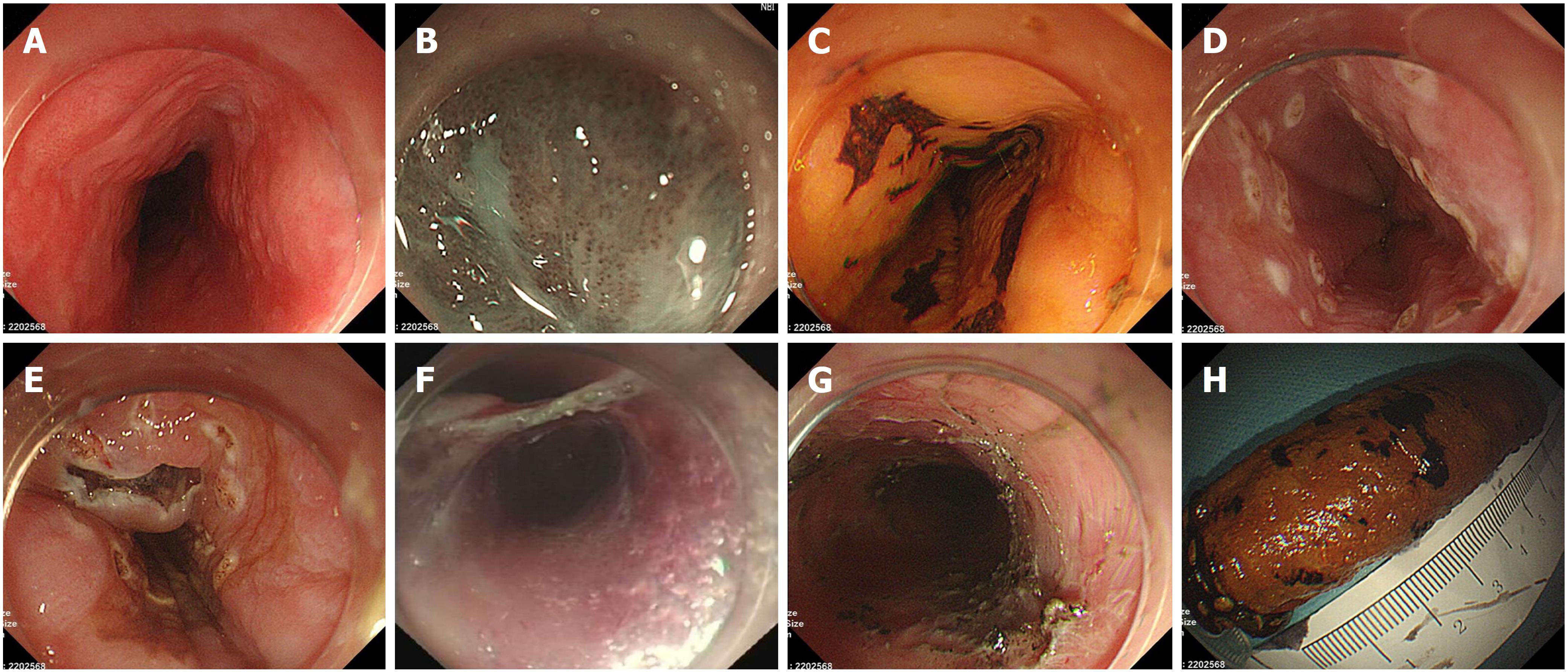

Before ESTD, all of the lesions were evaluated by endoscopy, enhanced ultrasound (EUS), and computed tomography (CT) of chest and abdomen. Prophylactic antibiotics were used in patients with large mucosal lesions (circumference ≥ 3/4) at half an hour before ESTD. ESTDs were performed by one endoscopist with an experience of more than 200 cases of ESD procedure. ESTD procedure included six steps, as shown in Figure 2. When the lesion was detected by white light endoscopy, it was carefully observed under narrow band imaging (NBI) and iodine staining. Next, the margins were marked by a dual knife (KD-650Q, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). A liquid mixture of 1:10000 adrenaline saline, sodium hyaluronate, glycerin fructose, and indigo carmine was used in submucosal injection. Both anal-side and oral-side incisions were made after submucosal injection, after which the submucosal tunnel was established from the oral side to the anal side and stopped at the anal-side incision. Thereafter, the remaining lateral margin incisions were made; thus, the lesion was completely resected. Finally, wound hemostasis was carefully performed by hemostatic forceps (FD-410LR, Olympus) or argon plasma coagulator (ERBE Corporation).

Patients were allowed to feed orally from the third day after ESTD, while treatment with proton pump inhibitors, hemostatics, and nutritional supports was initiated. The vital signs were monitored, and gas-related complications were closely detected, including subcutaneous emphysema, mediastinal emphysema, and pneumoperitoneum. All patients were asked to join in the follow-up plan, and surveillance endoscopy with iodine staining was performed at 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 mo after ESTD. Biopsies for suspicious lesions were also recommended. The patients with non-curative resection underwent either additional treatment (re-ESD, radiotherapy, surgery) or close surveillance.

The primary outcomes included en bloc resection rate, complete resection rate, and curative resection rate as well as the data acquired from ESTD procedure, such as procedure time, dissection speed, and the specimen area. The secondary outcomes were the rates of adverse events, including intraoperative and postoperative bleeding, perforation, muscular injury, postoperative infection, esophageal stricture, positive margin, and local tumor reoccurrence. The symptom score of esophageal stricture was assessed according to Stooler’s dysphagia score[16].

Procedure time was defined as the time from lesion marking to the termination of therapeutic endoscopy. Specimen area was calculated by the formula: S = (a + b)/2 × (c + d)/2, (a and b represent the maximum and minimum values of the length diameter, respectively, while c and d represent the maximum and minimum values of the width diameter, respectively). En bloc resection was defined as resection of the lesion by an entire specimen, while complete resection/R0 resection was defined as an en bloc resection with neoplasia-free margins (both horizontal and vertical margins). Curative resection was pathologically defined as a complete resection with a differentiated carcinoma with < 200 μm submucosal invasion and no lympho-vascular invasion.

Intraoperative bleeding was defined as blood volume > 50 mL and bleeding that could be effectively stopped in ESTD procedure. Postoperative bleeding was defined as the symptoms of hematemesis or/and melena, with hemoglobin levels being decreased by more than 20 g/L within 30 d after ESTD procedure[17]. Perforation was defined as a visible hole in the esophageal wall or the presence of subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax, mediastinal emphysema, or pneumoperitoneum.

Esophageal stricture was defined when the standard GIF-Q260J (Olympus) gastroscopy could not pass through the esophageal lumen and if the patient had dysphagia[18]. A positive margin was defined as the presence of a neoplastic cell in the horizontal or vertical margins. Residual tumor was defined as the presence of new tumor lesions in the primary resection site and its surrounding 1 cm area within 6 mo after ESTD. Tumor reoccurrence was defined as the presence of new tumor lesions in the primary resection site and its surrounding 1 cm area over 6 mo after ESTD.

Continuous variables are represented by average ± SD and were compared by Student’s t-test. Categorical variables are represented by the rate and evaluated by Pearson Chi square test or Fisher exact test (SPSS version 24.0, SPSS Inc, Armonk, NY, United States). P-value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

A total of 355 superficial esophageal patients underwent endoscopic treatments from March 1, 2013 to May 1, 2017, of which 66 patients were excluded for the following reasons: (1) Adenocarcinoma (n = 15); (2) EMR procedure (n = 10) or ESD procedure (n = 27); (3) incomplete lesion data (n = 6); and (4) lost to follow-up (n = 8), as shown in Figure 1. The demographic data are shown in Table 1. The average age of the patients was 61.39 ± 8.07 years with a male/female ratio of 2.17 (213/98). The lesions were mainly located in the middle third of the esophagus (64.31%). Thirty-one circumferential lesions were included in the final analysis (Table 1). The most common preoperative histological type was HGIN, as shown in Table 2.

| Category | ESTD (n = 311) |

| Sex, male/female | 213/98 |

| Age, yr, mean (range) | 61.4 ± 8.1 (40-83) |

| Tumor location | |

| Upper third | 24 (7.72) |

| Middle third | 200 (64.31) |

| Lower third | 87 (27.97) |

| Paris classification | |

| 0-I | 18 (5.79) |

| 0-IIa | 111 (35.69) |

| 0-IIb | 94 (30.23) |

| 0-IIc | 35 (11.25) |

| 0-IIa-IIc | 50 (16.08) |

| 0-III | 3 (0.96) |

| Circumferential level | |

| ≤ 1/4 | 11 (3.54) |

| ≤ 1/2 | 163 (52.41) |

| ≤ 3/4 | 65 (20.90) |

| ≤ 7/8 | 41 (13.18) |

| ≤ 1 | 31 (9.97) |

| Pathology | Pre-ESTD | Post-ESTD | Pre-ESTD and Post-ESTD coincidence |

| Inflammation | 0 | 3 (0.96) | 0 |

| LGIN | 67 (21.54) | 43 (13.83) | 36 (11.57) |

| HGIN | 159 (51.13) | 52 (16.72) | 37 (11.90) |

| M1 | 74 (23.79) | 74 (23.79) | 18 (5.79) |

| M2 | 11 (3.54) | 47 (15.11) | 3 (0.96) |

| M3 | 0 | 51 (16.40) | 0 |

| SM1 | 0 | 23 (7.40) | 0 |

| > SM1 | 0 | 18 (5.79) | 0 |

Three hundred eleven lesions were successfully resected from 289 patients. The average specimen area was 14.1 ± 3.6 cm2, the mean procedure time was 102.4 ± 35.3 min, and the mean dissection speed was 18.6 ± 2.1 mm2/min. A total of 308 (308/311) lesions were resected by en bloc (99.04%), of which 49 were diagnosed with horizontal or vertical margin involvement by pathological evaluation; thus, the R0 resection rate was 81.28% (259/311). Twelve patients were diagnosed with lympho-vascular invasion (3.86%), of which five were combined with positive margin. We evaluated the invasion depth under microscopy and observed that seven lesions had a submucosal invasion deeper than 200 μm. As a result, the curative resection rate was 78.46% (244/311). After post-ESTD pathological evaluation, three patients were diagnosed with residual cancer in horizontal margin and 12 in vertical margin, of which five patients had vascular invasion. Another seven patients simply showed vascular invasion. All of the 22 patients were recommended an additional surgery. Finally, 17 patients underwent surgery, while the other five refused and were closely observed. The mean hospitalization stay was 10.3 ± 2.8 d, while the average hospitalization expense was 3766.5 ± 846.5 dollars (Table 3).

| Category | ESTD (n = 311) |

| Specimen area, cm2, mean ± SD | 14.1 ± 3.6 |

| Tumor width diameter, cm, mean ± SD | 3.1 ± 0.6 |

| Tumor length diameter, cm, mean ± SD | 4.2 ± 0.9 |

| Procedure time, min, mean ± SD | 102.4 ± 35.3 |

| Dissection speed, mm2/ min, mean ± SD | 18.6 ± 2.1 |

| En bloc resection | 308 (99.04) |

| R0 resection | 259 (81.28) |

| Curative resection | 244 (78.46) |

| Hospitalization day, d, mean ± SD | 10.3 ± 2.8 |

| Hospitalization expense, dollars, mean ± SD | 3766.5 ± 846.5 |

After ESTD procedure, 30 patients had postoperative infection, of which 29 were pulmonary infection, and one was urinary-tract infection. All of the infections were cured by intravenous infusion of antibiotics. Moreover, 20 (6.43%) patients had intra-operative bleeding, and five patients had postoperative bleeding. All of these patients underwent endoscopic hemostasis, and no severe complications with regard to bleeding were observed. Six patients had esophageal perforation and were cured by conservative treatment. Forty-six patients had postoperative esophageal stricture, of which 36 (78.26%) underwent an average of 4.1 (2-19 times) endoscopic balloon dilations in a mean follow-up time of 20.2 mo. In addition, the dysphagia was almost relieved (Table 4), while the other 10 patients with obstinate stenosis were further managed by receiving endoscopic balloon dilatation every 2 wk till dysphagia was relieved.

| Category | ESTD (n = 311) |

| Post-operative infection | 30 (9.65) |

| Bleeding | |

| Intraoperative bleeding | 20 (6.43) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 5 (1.61) |

| Muscular injury | 98 (31.51) |

| Perforation | 6 (1.93) |

| Esophageal stricture | 46 (14.79) |

| Positive margin | |

| Horizontal margin | 35 (11.25) |

| Vertical margin | 10 (3.22) |

| Horizontal and vertical margin | 4 (1.29) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 12 (3.86) |

We analyzed the pathological change between pre-ESTD biopsies and post-ESTD specimens and observed that HGIN accounted for 51.13% (159/311) of pre-ESTD biopsies, while in post-ESTD pathology, superficial invasive carcinoma accounted for 44.70% (139/311). The pre-ESTD and post-ESTD coincidence rate was 30.23% (94/311). Also, 50.21% (117/233) of HGIN and M1 lesions had a pathological upgrade after ESTD to superficial invasive carcinoma.

This study evaluated the efficacy and complications of ESTD in 289 patients with 311 esophageal mucosal lesions. ESTD is a new technique developed from ESD and tunnel endoscopy. There are currently few studies that have reported the efficacy and complications of ESTD in large samples. Gan et al[13] reported endoscopic submucosal multi-tunnel dissection (ESMTD) for seven circumferential lesions, in which all patients achieved R0 resection but suffered from esophageal stricture. Huang et al[10] compared the efficacy and complication rate between ESD and ESTD using a propensity score matching analysis and observed that ESTD can improve procedure efficacy and reduce injury to muscular layer due to a better view, more efficient vessel coagulation, and longer lasting submucosal liquid cushion. In our previous ESD procedure, we observed that the dissected mucosa shrank and blocked the lumen, making it difficult to obtain a clear view. While ESTD can avoid this obstacle by creating a submucosal tunnel, when therapeutic endoscopy enters the submucosal tunnel, it will acquire a clear operative view to facilitate observation of the submucosal vessels and muscular layer, thereby reducing the bleeding and perforation rate. For this reason, it is especially appropriate for large mucosal lesions[11]. Zhai et al[19] obtained similar findings and noted that ESTD is indicated when (1) lesions do not invade deeper than sm1 and have no evidence of lymph node metastasis and (2) the lesion’s circumference level ≥ 1/3 or the diameter ≥ 2 cm.

The reported en bloc and R0 resection rates of ESTD were 97.8% (92%-100%) and 85.6%(81.8%-100%), which are similar to our study outcomes. However, our curative resection rate was 78.46% (244/311), mainly because we included large mucosal lesions. Also, 44.05% (137/311) of our lesions had a circumference level > 1/2, which may increase the risk of incomplete resection. Patients’ mean hospitalization stay was 10.3 ± 2.8 d, which is closely related to less hospitalization expenses (3766.5 ± 846.5 dollars) compared with surgical treatment.

We evaluated the post-ESTD specimens’ pathological features and observed that 50.21% (117/233) of HGIN and M1 lesions upgraded to superficial invasive carcinoma after ESTD. Several reasons might contribute to this: First, the heavier the lesion and the wider its range, the poorer the representativeness of the pre-ESTD biopsy. In large or multifocal lesions, even if multiple biopsies are taken, it is difficult to represent the whole picture of the lesion. Moreover, the esophagus wall is thin; thus, too deeply drawn or frequent biopsies will lead to bleeding, perforation, and other biopsy-related complications. Therefore, we think that the reference significance of preoperative biopsy requires further evaluation and should be combined with iodine staining, narrow band imaging with magnifying endoscopy (ME-NBI), and radiological examination.

Postoperative infection, bleeding, and perforation are common in ESD procedure. Previous studies reported the bleeding and perforation rates of ESD to be 0-6% and 1.7%-4.0%[20-22], respectively. In our study, the total bleeding rate and perforation rate associated with ESTD were 8.04% and 1.93%, respectively. The significant bleeding that needs postoperative hemostatic treatment is relatively low (1.61%), indicating that ESTD is a safe treatment method for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and precancerous lesions. Thirty (9.65%) patients had postoperative infection. There are no available studies that have reported on post-ESD infection, although it is relatively common especially for the elderly. We speculate that the infection is caused by the patient hypoimmunity and the history of previous pulmonary disease or inhalation pneumonia related to anesthesia; however, further studies are needed to confirm this etiology.

Esophageal stricture and positive margin are serious complications of ESTD procedure, and the incidence rates found in our study were 14.79% (46/311) and 15.76% (49/311), respectively. It was reported that the circumference level and the area of the lesion are risk factors for esophageal stricture[23,24]. The incidence rate of esophageal stricture in patients with circumference level > 3/4 is above 70%-90%[25,26]. When the lesion area is large enough, the artificial esophageal ulcer causes excess absence of epithelial cells and results in fibrous repair in the submucosa[27], which is the primary cause of esophageal stricture. To prevent esophageal stricture, the administration of steroids is useful, as previously reported[28,29], while endoscopic balloon dilation and esophageal stent implantation can also be options[30,31]. For positive margin, previous studies reported its incidence after ESD to be 3%-17%[18,32,33]. Wen reported that the lesion area and invasion depth are risk factors of positive margin[33], and hypothesized that a greater lesion area and deeper invasion level corresponded to higher positive rates of the incisal margin. When treating large and multiple lesions, the risk of positive margin is relatively high, and thus accurate preoperative labeling and intraoperative complete resection are important. There are no standard guidelines to address positive margin after endoscopic resection; therefore, we recommended additional surgery for all patients in our study with positive basal margin, horizontal margin carcinoma involvement, and vascular invasion; however, several patients refused and entered the follow-up cohort. No residual or recurrent tumor was observed during the follow-up period.

The present study is the largest sample research of ESTD technique to date, and our observation indicators are complete, the follow-up period is long, the results are credible, and there is strong reference significance in clinical work. Moreover, our study also performed a detailed evaluation of postoperative pathology and emphasized its guiding role in the postoperative management of the patients. However, this study has several limitations. Firstly, this was a retrospective study and thus has inherent case selection bias. Secondly, this was a single center study; therefore, the operation level of ESTD in this study cannot be fully represented in whole.

In conclusion, ESTD for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and precancerous lesions is effective and safe, exhibiting high en bloc resection rate as well as low bleeding and perforation rates. When using ESTD to resect large mucosal lesions, the incidence of postoperative esophageal stricture and positive margin is high, and thus other effective preventative measures should be considered. We also observed that preoperative biopsies cannot represent the whole specimen, while half of the biopsies’ pathology upgraded after ESTD procedure; therefore, the choice of therapy cases should be made cautiously before ESTD.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is becoming the standard treatment for early gastrointestinal cancers, as it has a higher en bloc resection rate and a lower recurrence rate than endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). However, when treating large mucosal lesions, ESD always faces many difficulties, such as multiple submucosal injections times, long procedure time, and low complete resection rate. To overcome these difficulties, a modified technique named endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection (ESTD) has been proposed. Compared with ESD, ESTD could reduce the number of submucosal injections, shorten the procedure time, increase the resection speed, and reduce the injury of the muscular layer. However, there are no studies that verify the feasibility of ESTD in superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and precancerous lesions in a large sample.

To our knowledge, the present study is the largest sample research of ESTD technique to date, and our observation indicators are complete, the follow-up period is long, the results are credible, and there is strong reference significance in clinical work.

This study aims to evaluate the clinical outcomes of patients who underwent ESTD for ESCC and precancerous lesions.

ESTD was performed in 289 patients with 311 lesions. The clinical outcomes of the patients and pathological features of the lesions were retrospectively reviewed.

A total of 311 lesions were included. The en bloc rate, complete resection rate, and curative resection rate were 99.04%, 81.28%, and 78.46%, respectively. The ESTD procedure time was 102.4 ± 35.1 min, the mean hospitalization time was 10.3 ± 2.8 d, and the average expenditure was 3766.5 ± 846.5 dollars. The intraoperative bleeding rate, postoperative bleeding rate, the perforation rate, and the postoperative infection rate were 6.43%, 1.61%, 1.93%, and 9.65%, respectively. Esophageal stricture and positive margin were severe adverse events, with an incidence rate of 14.79% and 15.76%, respectively. No tumor recurrence occurred during the follow-up period.

ESTD for ESCC and precancerous lesions is feasible and relatively safe, but the rates of esophageal stricture and positive margin are high for large mucosal lesions.

The present study is a retrospective study to describe the general characteristics of ESTD. In the future, case control studies and prospective studies are considered necessary to evaluate further the feasibility and safety of ESTD for treating ESCC and precancerous lesions.

| 1. | Lian J, Chen S, Zhang Y, Qiu F. A meta-analysis of endoscopic submucosal dissection and EMR for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:763-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Ishihara R, Iishi H, Uedo N, Takeuchi Y, Yamamoto S, Yamada T, Masuda E, Higashino K, Kato M, Narahara H. Comparison of EMR and endoscopic submucosal dissection for en bloc resection of early esophageal cancers in Japan. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1066-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T, Repici A, Vieth M, De Ceglie A, Amato A, Berr F, Bhandari P, Bialek A. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:829-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 817] [Cited by in RCA: 958] [Article Influence: 87.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Maeda Y, Hirasawa D, Fujita N, Obana T, Sugawara T, Ohira T, Harada Y, Yamagata T, Suzuki K, Koike Y. A pilot study to assess mediastinal emphysema after esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection with carbon dioxide insufflation. Endoscopy. 2012;44:565-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Linghu E, Feng X, Wang X, Meng J, Du H, Wang H. Endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection for large esophageal neoplastic lesions. Endoscopy. 2013;45:60-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tsao SK, Toyonaga T, Morita Y, Fujita T, Hayakumo T, Azuma T. Modified fishing-line traction system in endoscopic submucosal dissection of large esophageal tumors. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2:E119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xie X, Bai JY, Fan CQ, Yang X, Zhao XY, Dong H, Yang SM, Yu J. Application of clip traction in endoscopic submucosal dissection to the treatment of early esophageal carcinoma and precancerous lesions. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:462-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Koike Y, Hirasawa D, Fujita N, Maeda Y, Ohira T, Harada Y, Suzuki K, Yamagata T, Tanaka M. Usefulness of the thread-traction method in esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection: randomized controlled trial. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:303-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Linghu E. Therapeutics of Digestive Endoscopic Tunnel Technique. Berlin, Springer Netherlands. 2014;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Huang R, Cai H, Zhao X, Lu X, Liu M, Lv W, Liu Z, Wu K, Han Y. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a propensity score matching analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:831-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang J, Qin JY, Guo TJ, Gan T, Wang YP, Wu JC. The Efficiency and Complications of ESD and ESTD in the Treatment of Large Esophageal Mucosal Lesions. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2015;46:896-900. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Zhai Y, Linghu E, Li H, Qin Z, Feng X, Wang X, Du H, Meng J, Wang H, Zhu J. [Comparison of endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection with endoscopic submucosal dissection for large esophageal superficial neoplasms]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2014;34:36-40. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Gan T, Yang JL, Zhu LL, Wang YP, Yang L, Wu JC. Endoscopic submucosal multi-tunnel dissection for circumferential superficial esophageal neoplastic lesions (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:143-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Japan Esophageal Society. Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer, 11th Edition: part I. Esophagus. 2017;14:1-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 740] [Article Influence: 82.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-S43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1117] [Cited by in RCA: 1380] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 16. | Loizou LA, Grigg D, Atkinson M, Robertson C, Bown SG. A prospective comparison of laser therapy and intubation in endoscopic palliation for malignant dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1303-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Qumseya BJ, Wolfsen C, Wang Y, Othman M, Raimondo M, Bouras E, Wolfsen H, Wallace MB, Woodward T. Factors associated with increased bleeding post-endoscopic mucosal resection. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:140-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Joo DC, Kim GH, Park DY, Jhi JH, Song GA. Long-term outcome after endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a single-center study. Gut Liver. 2014;8:612-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhai YQ, Li HK, Linghu EQ. Endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection for large superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:435-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Oyama T, Tomori A, Hotta K, Morita S, Kominato K, Tanaka M, Miyata Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early esophageal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S67-S70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 461] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ono S, Fujishiro M, Niimi K, Goto O, Kodashima S, Yamamichi N, Omata M. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:860-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sohara N, Hagiwara S, Arai R, Iizuka H, Onozato Y, Kakizaki S. Can endoscopic submucosal dissection be safely performed in a smaller specialized clinic? World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:528-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ono S, Fujishiro M, Niimi K, Goto O, Kodashima S, Yamamichi N, Omata M. Predictors of postoperative stricture after esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial squamous cell neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2009;41:661-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Katada C, Muto M, Manabe T, Boku N, Ohtsu A, Yoshida S. Esophageal stenosis after endoscopic mucosal resection of superficial esophageal lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:165-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ezoe Y, Muto M, Horimatsu T, Morita S, Miyamoto S, Mochizuki S, Minashi K, Yano T, Ohtsu A, Chiba T. Efficacy of preventive endoscopic balloon dilation for esophageal stricture after endoscopic resection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:222-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Hashimoto S, Kobayashi M, Takeuchi M, Sato Y, Narisawa R, Aoyagi Y. The efficacy of endoscopic triamcinolone injection for the prevention of esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1389-1393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 27. | Honda M, Nakamura T, Hori Y, Shionoya Y, Yamamoto K, Nishizawa Y, Kojima F, Shigeno K. Feasibility study of corticosteroid treatment for esophageal ulcer after EMR in a canine model. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:866-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ratone JP, Bories E, Caillol F, Pesenti C, Godat S, Poizat F, Cassan C, Giovannini M. Oral steroid prophylaxis is effective in preventing esophageal strictures after large endoscopic resection. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30:62-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yamaguchi N, Isomoto H, Nakayama T, Hayashi T, Nishiyama H, Ohnita K, Takeshima F, Shikuwa S, Kohno S, Nakao K. Usefulness of oral prednisolone in the treatment of esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1115-1121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Sato H, Inoue H, Kobayashi Y, Maselli R, Santi EG, Hayee B, Igarashi K, Yoshida A, Ikeda H, Onimaru M. Control of severe strictures after circumferential endoscopic submucosal dissection for esophageal carcinoma: oral steroid therapy with balloon dilation or balloon dilation alone. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:250-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yano T, Yoda Y, Nomura S, Toyosaki K, Hasegawa H, Ono H, Tanaka M, Morimoto H, Horimatsu T, Nonaka S. Prospective trial of biodegradable stents for refractory benign esophageal strictures after curative treatment of esophageal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:492-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Repici A, Hassan C, Carlino A, Pagano N, Zullo A, Rando G, Strangio G, Romeo F, Nicita R, Rosati R. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: results from a prospective Western series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:715-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Wen J, Linghu E, Yang Y, Liu Q, Wang X, Du H, Wang H, Meng J, Lu Z. Relevant risk factors and prognostic impact of positive resection margins after endoscopic submucosal dissection of superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasia. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1653-1659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Kosugi S, Ide E S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Yin SY