Published online Jul 14, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i26.2886

Peer-review started: March 20, 2018

First decision: April 24, 2018

Revised: May 2, 2018

Accepted: June 2, 2018

Article in press: June 2, 2018

Published online: July 14, 2018

Processing time: 115 Days and 9.9 Hours

To determine whether the number of examined lymph nodes (LNs) is correlated with the overall survival of gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) patients.

Patients were collected from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database (2004-2013) and categorized by the number of LNs into six groups: 1 LN, 2 LNs, 3 LNs, 4 LNs, 5 LNs, and ≥ 6 LNs. Survival curves for overall survival were plotted with a Kaplan-Meier analysis. The log-rank test was used for univariate comparisons.

In a cohort of 893 patients, the median number of examined LNs was two for the entire cohort. The survival for the 1 LN group was significantly poorer than those of the stage I and II disease groups and for the entire cohort. By dichotomizing the number of LNs from 1 to 6, we found that the minimum number of LNs that should be examined was four for stage I, four or five for stage II, and six for stage IIIA disease. Therefore, for the entire cohort, the number of examined LNs should be at least six, which is exactly consistent with the American Joint Committee on Cancer criteria.

The examination of higher numbers of LNs is associated with improved survival after resection surgery for N0 GBC. The guidelines for GBC surgery, which recommend that six LNs be examined at least, are statistically valid and should be applied in clinical practice widely.

Core tip: Six lymph nodes were recommended as the minimum number of examination in the 8th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor-node-metastasis criteria for gallbladder carcinoma, but the rationality has not been evaluated yet. Thus, we aimed to explore the optimal lymph node number using the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database.

- Citation: Fan DX, Xu RW, Li YC, Zhao BQ, Sun MY. Impact of the number of examined lymph nodes on outcomes in patients with lymph node-negative gallbladder carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(26): 2886-2892

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i26/2886.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i26.2886

Gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) is one of the most lethal carcinomas and has a poor prognosis[1-3]. To date, surgery remains the only radical treatment strategy for patients, translating into 5-year survival rates of approximately 5%[4-7]. Lymph node (LN) status is an important prognostic factor for GBC patients[8]. Unfortunately, LN metastases occur in more than 50% of patients, and LN-positive patients are widely known to have very poor survival[4].

The role of regional and extended lymphadenectomy for GBC has been previously investigated[9-12], but there is not a general consensus about the number of LNs that should be examined. In the 8th edition of the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system for GBC from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), the N category was defined by the number of metastatic LNs instead of the location of the metastatic LNs, as used in the previous edition, and was correlated with prognosis. These guidelines recommend examining a minimum of six LNs to accurately classify patients with GBC[13]. Thus, this study aimed to assess patients with LN-negative (N0) GBC to determine whether the number of examined LNs was correlated with overall survival of GBC patients. We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result (SEER) database to determine the influence of the number of examined LNs on prognosis in patients with N0 GBC.

The SEER database (2004-2013) was used to identify patients with GBC. Patients who met the following criteria were included: (1) Pathologically confirmed diagnosis; (2) radical surgical treatment; (3) definite cancer stage according to the 8th edition of the AJCC criteria; (4) first primary tumor; (5) number of positive LNs equal to zero; (6) no distant metastases; (7) one or more LNs examined; and (8) active follow-up. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age < 18 years; (2) unavailable follow-up data or 0 d of follow-up; (3) unknown cause of death; (4) number of LNs examined coded with SEER codes 95 to 99 (the information about the number of LN is not available); and (5) T4 disease.

The clinicopathological characteristics were compared among the stage I, II, and IIIA disease subgroups by the independent t test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Overall survival (OS) was determined from the SEER record of survival time (total number of months) and vital status. The relationship between the number of examined LNs and OS was assessed separately for the entire cohort and for stage I, II, and IIIA patients. Patients were categorized by the number of examined LNs into the following six groups: 1 LN, 2 LNs, 3 LNs, 4 LNs, 5 LNs, and ≥ 6 LNs. The optimal number of examined LNs was determined with X-tile software (Yale University, Version 3.6.1). Survival curves for OS were plotted with a Kaplan-Meier analysis. The log-rank test was used for univariate comparison. A Cox proportional hazard method was used to identify factors associated with mortality and to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The variables, including age, sex, race, radiation therapy, number of examined LNs, grade, and stage, that were significant in univariate analysis, were included in the Cox model. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 20 (Armonk, NY, United States). A two-tailed P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Among the 893 patients who were finally eligible for this analysis, 228 patients (25.5%) had stage I disease, 444 patients (49.7%) had stage II disease, and 221 patients (24.7%) had stage IIIA disease. The median age at diagnosis for the entire cohort was 67 years (range 21-96 years), and 272 patients (30.5%) were male.

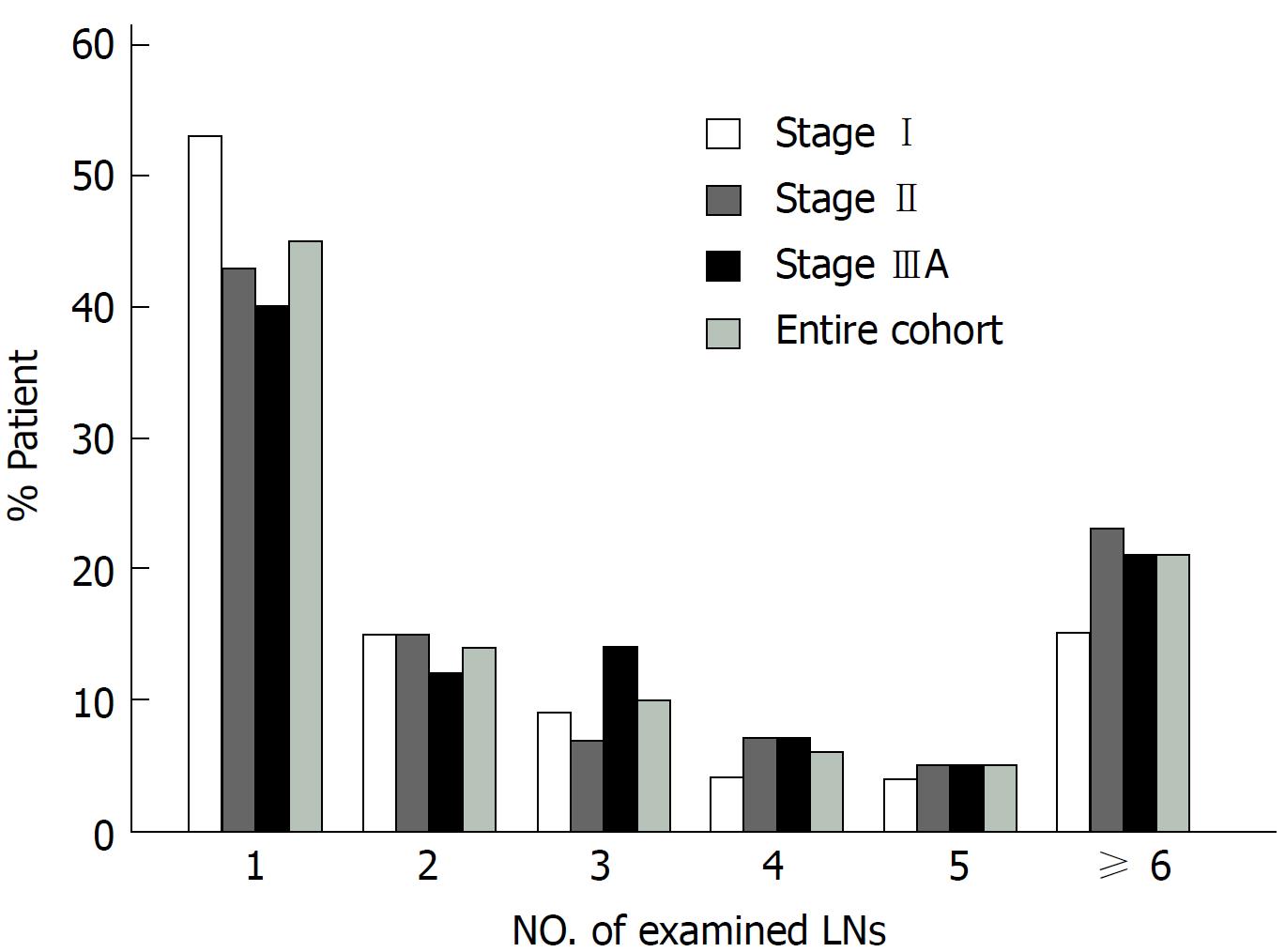

The clinical characteristics of the entire cohort and patients with stage I, II, and IIIA disease are listed in Table 1. There was no difference among patients with stage I, II, or IIIA disease in terms of age, sex, race, and number of LNs examined. In addition, compared with patients with stage I and II disease, a larger proportion of patients with stage IIIA disease had poor/undifferentiated tumors and received radiation therapy. The median number of examined LNs was 2 for the entire cohort, 1 LN for the stage I group, 2 LNs for the stage II group, and 2 LNs for the stage IIIA group. More than 40% of the patients had only 1 LN examined, and a lower proportion of patients had more LNs examined (Figure 1). The number of examined LNs did not differ by stage (P = 0.59).

| Characteristics | Entire cohortn = 893 (100%) | Stage I1n = 228 (25.5%) | Stage II1n = 444 (49.7%) | Stage IIIA1n = 221 (24.7%) | P2Value |

| Age, yr | |||||

| Median (range) | 67 (21-96) | 67 (21-92) | 67 (25-96) | 67 (35-93) | 0.575 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 272 (30.5) | 63 (27.6) | 139 (31.3) | 70 (31.7) | |

| Female | 621 (69.5) | 165 (72.4) | 305 (68.7) | 151 (68.3) | 0.559 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 675 (75.6) | 162 (71.1) | 34.1 (76.8) | 172 (77.8) | |

| Black | 106 (11.9) | 33 (14.5) | 50 (11.3) | 23 (10.4) | |

| Others | 112 (12.5) | 33 (14.5) | 53 (11.9) | 26 (11.8) | 0.261 |

| Grade1 | |||||

| Well | 187 (20.9) | 67 (29.4) | 102 (23.0) | 18 (8.1) | |

| Moderate | 414 (46.4) | 101 (44.3) | 215 (48.4) | 98 (44.3) | |

| Poor | 210 (23.5) | 26 (11.4) | 96 (21.6) | 88 (39.8) | |

| Undifferentiated | 11 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (1.1) | 5 (2.3) | |

| Unknown | 71 (8.0) | 33 (14.5) | 26 (5.9) | 12 (5.4) | < 0.001 |

| Radiation | |||||

| Yes | 151 (16.9) | 8 (3.5) | 75 (16.9) | 68 (30.8) | |

| No | 742 (83.1) | 220 (96.5) | 369 (83.1) | 153 (69.2) | < 0.001 |

| Vital status | |||||

| Alive | 547 (61.3) | 151 (66.2) | 308 (69.4) | 88 (39.8) | |

| Dead | 346 (38.7) | 77 (33.8) | 136 (30.6) | 133 (60.2) | < 0.001 |

| Number of LN | |||||

| Median (range) | 2 (1-80) | 1 (1-80) | 2 (1-40) | 2 (1-24) | 0.590 |

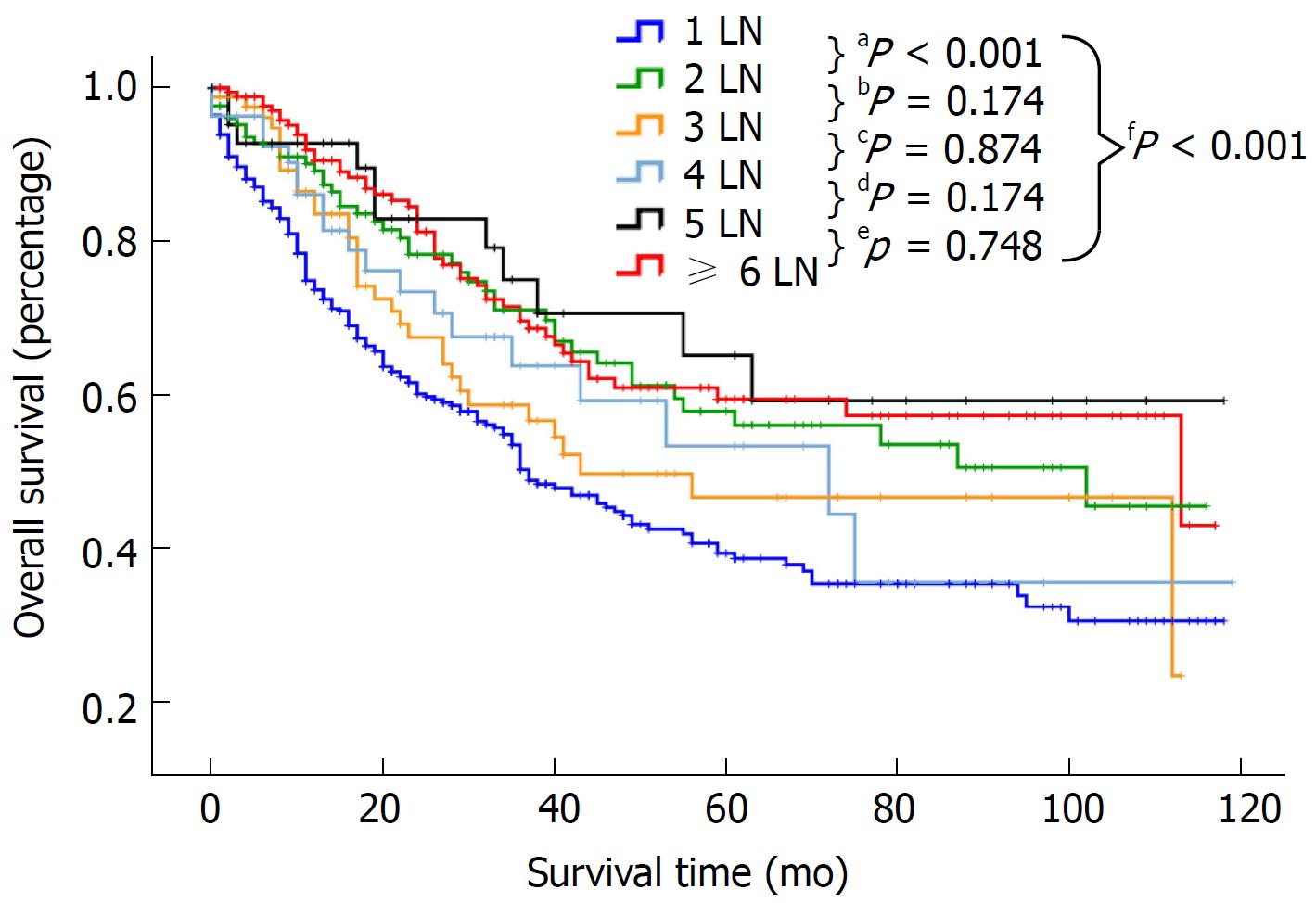

Patients were categorized by the number of examined LNs into the following 6 groups: 1 LN, 2 LNs, 3 LNs, 4 LNs, 5 LNs and ≥ 6 LNs. Survival in relation to the number of examined LNs was assessed separately for the entire cohort and patients with stage I, II and IIIA disease (Table 2). For the entire cohort, a median survival of 18 mo and a 5-year survival rate of 0.393 were noted for patients with one LN examined (n = 398). The survival for the 1 LN group was significantly poorer than that of the other groups (P < 0.001, Figure 2). However, there was no difference in survival among the other five groups (P > 0.05). For patients with stage I disease, the median survival for the 1 LN, 2 LNs, 3 LNs, 4 LNs, 5 LNs, and ≥ 6 LNs groups was 24, 43, 30, 22, 38, and 26 mo, respectively. Similar survival results according to the LN groups were demonstrated for patients with stage I and II disease but not for patients with stage IIIA disease (Table 2). However, compared with patients with stage I and II disease, the median survival and 5-year survival rate of patients with stage IIIA disease was obviously decreased in all the LN groups. For example, the 5-year survival rate in the 1 LN group was 0.473 for stage I, 0.445 for stage II, and 0.177 for stage IIIA disease. As shown in Table 3, there was no difference in survival between the stage I and II groups (HR: 1.089, 95%CI: 0.793-1.497, P = 0.598 for stage II, referred to stage I), but the survival of patients with stage IIIA disease was significantly lower than that of patients with stage I disease (HR: 3.730, 95%CI: 2.635-5.280, P < 0.0001).

| Number of LN | Entire cohort n = 893 (100%) | Stage I1n = 228 (25.5%) | Stage II1n = 444 (49.7%) | Stage IIIA1n = 221 (24.7%) |

| 1 LN | ||||

| Patients (n) | 398 | 121 | 189 | 88 |

| Median OS, mo | 18 | 24 | 20 | 10 |

| 3-yr SR (95%CI) | 0.503 (0.474-0.532) | 0.603 (0.553-0.653) | 0.608 (0.566-0.650) | 0.271 (0.217-0.325) |

| 5-yr SR (95%CI) | 0.393 (0.361-0.425) | 0.473 (0.418-0.528) | 0.445 (0.394-0.496) | 0.177 (0.128-0.226) |

| 2 LNs | ||||

| Patients (n) | 129 | 35 | 68 | 26 |

| Median OS, mo | 28 | 43 | 27 | 15 |

| 3-yr SR (95%CI) | 0.711 (0.665-0.757) | 0.808 (0.737-0.879) | 0.775 (0.713-0.837) | 0.425 (0.317-0.533) |

| 5-yr SR (95%CI) | 0.579 (0.524-0.634) | 0.725 (0.640-0.810) | 0.586 (0.504-0.668) | 0.340 (0.225-0.455) |

| 3 LNs | ||||

| Patients (n) | 85 | 20 | 33 | 32 |

| Median OS, mo | 21 | 30 | 27 | 11 |

| 3-yr SR (95%CI) | 0.587 (0.525-0.649) | 0.722 (0.603-0.841) | 0.697 (0.606-0.788) | 0.379 (0.277-0.481) |

| 5-yr SR (95%CI) | 0.466 (0.396-0.536) | 0.602 (0.454-0.750) | 0.639 (0.539-0.739) | 0.203 (0.109-0.297) |

| 4 LNs | ||||

| Patients (n) | 55 | 8 | 31 | 16 |

| Median OS, mo | 22 | 22 | 27 | 10 |

| 3-yr SR (95%CI) | 0.638 (0.560-0.716) | 0.833 (0.681-0.985) | 0.760 (0.671-0.849) | 0.295 (0.154-0.446) |

| 5-yr SR (95%CI) | 0.533 (0.438-0.628) | 0.833 (0.681-0.985) | 0.652 (0.526-0.778) | 0.148 (0.022-0.274) |

| 5 LNs | ||||

| Patients (n) | 43 | 10 | 21 | 12 |

| Median OS, mo | 24 | 38 | 24 | 18 |

| 3-yr SR (95%CI) | 0.750 (0.671-0.829) | 0.857 (0.725-0.989) | NA | 0.292 (0.133-0.451) |

| 5-yr SR (95%CI) | 0.652 (0.557-0.747) | 0.714 (0.543-0.885) | 0.857 (0.725-0.989) | 0.146 (0.016-0.276) |

| ≥ 6 LNs | ||||

| Patients (n) | 183 | 34 | 102 | 47 |

| Median OS, mo | 26 | 26 | 26 | 21 |

| 3-yr SR (95%CI) | 0.696 (0.655-0.737) | 0.817 (0.731-0.903) | 0.753 (0.701-0.805) | 0.498 (0.412-0.584) |

| 5-yr SR (95%CI) | 0.594 (0.547-0.641) | 0.817 (0.731-0.903) | 0.671 (0.610-0.732) | 0.306 (0.221-0.391) |

| Variable | Entire cohortn = 893 (100%) | Stage I1n = 228 (25.5%) | Stage II1n = 444 (49.7%) | Stage IIIA1n = 221 (24.7%) | ||||

| HR (95%CI) | aP | HR (95%CI) | bP | HR (95%CI) | cP | HR (95%CI) | dP | |

| Age, yr | 1.001 (1.000-1.002) | 0.504 | 1.001 (1.000-1.002) | 0.934 | 1.001 (1.000-1.002) | 0.449 | 1.001 (1.000-1.002) | 0.057 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 0.684 (0.532-0.879) | 0.003 | 0.317 (0.156-0.645) | 0.002 | 0.553 (0.346-0.881) | 0.013 | 0.494 (0.299-0.818) | 0.006 |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Black | 1.475 (1.008-2.160) | 0.046 | 4.593 (1.625-12.981) | 0.004 | 1.645 (0.775-3.490) | 0.195 | 2.245 (0.904-5.575) | 0.082 |

| Others | 0.821 (0.551-1.224) | 0.334 | 0.262 (1.975) | 0.719 | 0.509 (0.245-1.056) | 0.070 | 1.362 (0.609-3.047) | 0.452 |

| Grade1 | ||||||||

| Well | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Moderate | 0.840 (0.609-1.157) | 0.286 | 0.418 (0.194-0.902) | 0.026 | 1.568 (0.905-2.715) | 0.109 | 0.297 (0.125-0.704) | 0.006 |

| Poor | 1.291 (0.908-1.835) | 0.155 | 1.339 (0.449-3.994) | 0.601 | 2.412 (1.306-4.453) | 0.005 | 0.629 (0.259-1.531) | 0.307 |

| Undifferentiated | 2.101 (0.891-4.954) | 0.090 | / | / | 4.059 (1.033-15.951) | 0.045 | 1.434 (0.323-6.373) | 0.636 |

| Unknown | 0.856 (0.503-1.455) | 0.565 | 0.384 (0.134-1.106) | 0.076 | 2.376 (0.857-6.583) | 0.096 | 0.260 (0.068-1.003) | 0.050 |

| Radiation | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.727 (0.515-1.027) | 0.071 | 1.055 (0.302-3.688) | 0.933 | 0.781 (0.430-1.419) | 0.417 | 0.390 (0.215-0.708) | 0.002 |

| No. of LNs examined | 1.001 (1.000-1.002) | 0.162 | 1.001 (1.000-1.002) | 0.910 | 1.001 (1.000-1.002) | 0.382 | 1.001 (1.000-1.002) | 0.167 |

| Stage1 | ||||||||

| I | 1 | / | / | / | / | / | / | |

| II | 1.089 (0.793-1.497) | 0.598 | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| IIIA | 3.730 (2.635-5.280) | 0.000 | / | / | / | / | / | / |

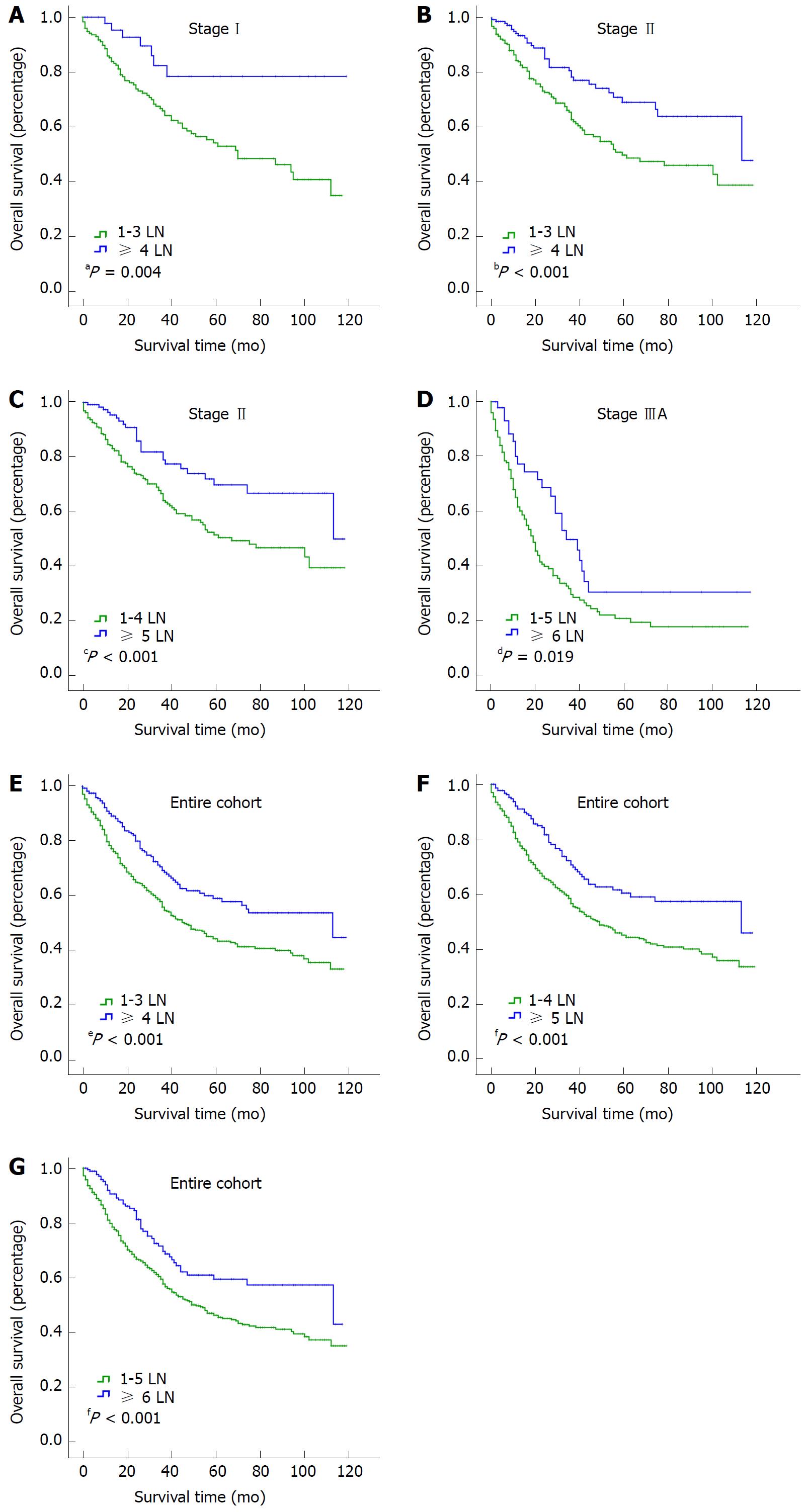

To identify the cutoff point for the optimal number of examined LNs, we compared the survival of the entire cohort with stage I, II and IIIA groups with X-tile software. The ranges for the significant dichotomization LN numbers varied among the three stages. The largest survival difference was observed at 4 LNs for stage I disease (P = 0.004; Figure 3A), at 4 or 5 LNs for stage II disease (P < 0.001 for both; Figure 3B and C), and at 6 LNs for stage IIIA disease (P = 0.019; Figure 3D). For the entire cohort, the optimal number of examined LNs was 4, 5, or 6 (P < 0.001 for all; Figure 3E-G).

A stepwise Cox regression identified race and sex as significant prognostic factors for the entire cohort (Table 3); however, race was not a significant factor for patients with stage II and IIIA disease. Grade was a significant prognostic factor for patients with stage I, II, and IIIA disease but not for the entire cohort; and radiation therapy was a significant prognostic factor only for patients with stage IIIA disease.

GBC is associated with a high incidence of invasion through the layers of the gallbladder wall into adjacent structures and LNs. The influence of LN metastases on primary GBC is supported by one series of reports, which showed that the 5-year survival rate of T1N0 patients was 33% compared with a 3% survival rate in T1N1 patients[14]. As a consequence, several large-scale studies were conducted to examine the role of extended LN dissection to determine whether the removal of additional LN basins would influence the survival of GBC patients[9,15].

Early retrospective reports suggested improved survival for late-stage GBC patients treated with extended regional lymphadenectomy compared with standard regional lymphadenectomy[9]. However, the minimum clearance and/or number of LNs that should be examined have yet to be established. In the study, we evaluated the impact of the number of examined LNs on survival in N0 GBC. Using the SEER database, we discovered that the median number of examined LNs was two for the entire cohort, one for stage I, two for stage II, and two for stage IIIA disease. We used the smallest median value, 1 LN, as the basis for our categorization of the SEER patient cohort into six groups that reflected the extent of lymphadenectomy: 1 LN, 2 LNs, 3 LNs, 4 LNs, 5 LNs, and ≥ 6 LNs. There was a significant difference in survival among the six groups for the entire cohort and for the stage I and II groups but not for the stage IIIA group. With X-tile software, we found that the minimum number of LNs that should be examined was four for stage I, four or five for stage II, and six for stage IIIA disease. Therefore, for the entire cohort, the number of examined LNs should be at least six, which is exactly consistent with the AJCC guidelines.

The general phenomenon that the more LNs are examined, the better the survival for N0 disease, has some potential explanations. For example, the final LN count may be a proxy for surgeon experience and surgical technique and may be reflective of more thorough pathological assessment and identification of nodes from the surgical specimen[16]. It is also related to the concept of stage migration, where inadequate removal of LNs may result in the misclassification of LN-positive patients as N0[17] . However, the removal of too many LNs may result in side effects such as lymphatic leakage. Our results were consistent with those of previous studies that investigated the relationship between LN count and survival in GBC patients and demonstrated that at least six LNs should be examined to improve survival after resection surgery[18]. Notably, except for LN dissection, nerve dissection may be required, especially for T3 or T4 disease[19].

In conclusion, the analysis suggests that examining higher numbers of LNs is associated with improved survival after resection surgery in N0 GBC. As recommended in the AJCC guidelines, at least six LNs should be examined for patients with N0 GBC.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor-node-metastasis staging system for gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) has been updated recently to the 8th edition. The N category is re-defined by the number of metastatic lymph nodes (LNs) instead of the location of the metastatic LNs, as defined in the 7th edition.

The new staging system for GBC has not been validated yet. Thus, we used Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result (SEER) database to evaluate its impact on clinical practice.

The primary purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of the number of examined LNs on the prognosis of N0 GBC. The secondary purpose was to verify the rationality of the guideline recommendation that at least six LNs should be harvested and evaluated.

Patients were collected from the SEER database (2004-2013) and categorized by the number of LNs into six groups: 1 LN, 2 LNs, 3 LNs, 4 LNs, 5 LNs, and ≥ 6 LNs. Survival curves for overall survival were plotted with a Kaplan-Meier analysis. The log-rank test was used for univariate comparisons.

The survival for the 1 LN group was significantly lower than that of the stage I and II disease groups and for the entire cohort. By dichotomizing the number of LNs from one to six, we found that the minimum number of LNs that should be examined was four for stage I, four or five for stage II, and six for stage IIIA disease. Thus, at least six LNs should be examined for the entire cohort, which was exactly consistent with the AJCC criteria.

The examination of higher numbers of LNs is associated with improved survival after resection surgery for N0 GBC. As recommended in the guidelines, at least six LNs should be examined for patients with N0 GBC.

The results validated the new recommendation in the AJCC guidelines, which can be applied widely in clinical practice.

| 1. | Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC, Sharma ID. Carcinoma of the gallbladder. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:167-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 480] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Randi G, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Gallbladder cancer worldwide: geographical distribution and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1591-1602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Meriggi F. Gallbladder carcinoma surgical therapy. An overview. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:333-335. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Zhu AX, Hong TS, Hezel AF, Kooby DA. Current management of gallbladder carcinoma. Oncologist. 2010;15:168-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Reid KM, Ramos-De la Medina A, Donohue JH. Diagnosis and surgical management of gallbladder cancer: a review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:671-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chan SY, Poon RT, Lo CM, Ng KK, Fan ST. Management of carcinoma of the gallbladder: a single-institution experience in 16 years. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:156-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hong EK, Kim KK, Lee JN, Lee WK, Chung M, Kim YS, Park YH. Surgical outcome and prognostic factors in patients with gallbladder carcinoma. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2014;18:129-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yamaguchi K, Chijiiwa K, Saiki S, Nishihara K, Takashima M, Kawakami K, Tanaka M. Retrospective analysis of 70 operations for gallbladder carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1997;84:200-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang JD, Liu YB, Quan ZW, Li SG, Wang XF, Shen J. Role of regional lymphadenectomy in different stage of gallbladder carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:593-596. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ott R, Hauss J. Need and extension of lymph node dissection in gallbladder carcinoma. Zentralbl Chir. 2006;131:474-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sasaki R, Takeda Y, Hoshikawa K, Takahashi M, Funato O, Nitta H, Murakami M, Kawamura H, Suto T, Yaegashi Y. Long-term results of central inferior (S4a+S5) hepatic subsegmentectomy and pancreatoduodenectomy combined with extended lymphadenectomy for gallbladder carcinoma with subserous or mild liver invasion (pT2-3) and nodal involvement: a preliminary report. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:215-218. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Niu GC, Shen CM, Cui W, Li Q. Surgical treatment of advanced gallbladder cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2015;38:5-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tang Z, Tian X and Wei M. Updates and interpretations of the 8th edition of AJCC cancer staging system for biliary tract carcinoma. Chinese Journal of Practical Surgery. 2017;37:248-254. |

| 14. | Rückert JC, Rückert RI, Gellert K, Hecker K, Müller JM. Surgery for carcinoma of the gallbladder. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:527-533. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kondo S, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, Kamiya J, Nagino M, Kanai M, Uesaka K, Yuasa N, Sano T. [Value of paraaortic lymphadenectomy for gallbladder carcinoma]. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;99:728-732. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Hellan M, Sun CL, Artinyan A, Mojica-Manosa P, Bhatia S, Ellenhorn JD, Kim J. The impact of lymph node number on survival in patients with lymph node-negative pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2008;37:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1604-1608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1124] [Cited by in RCA: 1153] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ito H, Ito K, D’Angelica M, Gonen M, Klimstra D, Allen P, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Accurate staging for gallbladder cancer: implications for surgical therapy and pathological assessment. Ann Surg. 2011;254:320-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ishihara S, Miyakawa S, Takada T, Takasaki K, Nimura Y, Tanaka M, Miyazaki M, Nagakawa T, Kayahara M, Horiguchi A. Status of surgical treatment of biliary tract cancer. Dig Surg. 2007;24:131-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Hori T, Voutsadakis IA S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Yin SY