Published online Dec 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i48.8615

Peer-review started: September 3, 2017

First decision: September 13, 2017

Revised: September 29, 2017

Accepted: November 21, 2017

Article in press: November 21, 2017

Published online: December 28, 2017

Processing time: 117 Days and 8.3 Hours

To assess the cleansing efficacy and safety of a new Colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) bowel preparation regimen.

This was a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled study comparing two CCE regimens. Subjects were asymptomatic and average risk for colorectal cancer. The second generation CCE system (PillCam® COLON 2; Medtronic, Yoqneam, Israel) was utilized. Preparation regimens differed in the 1st and 2nd boosts with the Study regimen using oral sulfate solution (89 mL) with diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium solution (“diatrizoate solution”) (boost 1 = 60 mL, boost 2 = 30 mL) and the Control regimen oral sulfate solution (89 mL) alone. The primary outcome was overall and segmental colon cleansing. Secondary outcomes included safety, polyp detection, colonic transit, CCE completion and capsule excretion ≤ 12 h.

Both regimens had similar cleansing efficacy for the whole colon (Adequate: Study = 75.9%, Control = 77.3%; P = 0.88) and individual segments. In the Study group, CCE completion was superior (Study = 90.9%, Control = 76.9%; P = 0.048) and colonic transit was more often < 40 min (Study = 21.8%, Control = 4%; P = 0.0073). More Study regimen subjects experienced adverse events (Study = 19.4%, Control = 3.4%; P = 0.0061), and this difference did not appear related to diatrizoate solution. Adverse events were primarily gastrointestinal in nature and no serious adverse events related either to the bowel preparation regimen or the capsule were observed. There was a trend toward higher polyp detection with the Study regimen, but this did not achieve statistical significance for any size category. Mean transit time through the entire gastrointestinal tract, from ingestion to excretion, was shorter with the Study regimen while mean colonic transit times were similar for both study groups.

A CCE bowel preparation regimen using oral sulfate solution and diatrizoate solution as a boost agent is effective, safe, and achieved superior CCE completion.

Core tip: Current bowel preparation boost agents for colon capsule endoscopy have associated risks and contraindications. This paper describes a new boost agent comprised of two very low dose hyperosmotic agents, oral sodium sulfate and diatrizoate solution, which appears to be an acceptable alternative regimen for colon capsule endoscopy.

- Citation: Kastenberg D, Jr WCB, Romeo DP, Kashyap PK, Pound DC, Papageorgiou N, Sainz IFU, Sokach CE, Rex DK. Multicenter, randomized study to optimize bowel preparation for colon capsule endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(48): 8615-8625

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i48/8615.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i48.8615

Colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) is a non-invasive procedure which effectively visualizes the entire colon. While CCE technology has advanced, the preparation regimen remains a challenge. Not only is a clean and fluid filled colon requisite, but the capsule must reach the hemorrhoidal plexus within its 12-h battery life. Furthermore, the capsule must dwell for a sufficient period of time within the colon as rapid transit (< 40 min) in combination with sub-optimal cleansing may lower the sensitivity for detecting polyps[1].

The CCE preparation regimen before capsule ingestion focuses on cleansing the colon, whereas post-capsule ingestion measures are aimed at propelling the capsule through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and providing additional cleansing. A full dose purgative, typically polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution (PEG-ELS), is administered as a split dose prior to capsule ingestion. After capsule ingestion, a pro-kinetic medication - in the United States metoclopramide - may be administered if the capsule does not exit the stomach within an hour. Upon entering the duodenum, and then typically 3 and 5 h later if the capsule has not exited the colon, an agent (“boost”) is administered to accelerate capsule transit and augment cleansing.

Generally the first and second boost consists of a hyperosmotic agent and, to date, sodium phosphate liquid (NaP) has most commonly been used[2-10]. However, numerous contraindications to the use of NaP makes it a non-viable option in the United States[11,12]. As an alternative to NaP, a large prospective CCE study used oral sulfate solution (OSS) for the first 177 mL (6 oz.) and second 89 mL (3 oz.) boost[1]. While overall bowel preparation adequacy was acceptable, an unexpected limitation of this regimen was a higher than expected rate of technically inadequate studies due to the combination of rapid colonic transit and inadequate colon cleansing.

Diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium solution (“diatrizoate solution”) is a hyperosmotic agent used in radiologic imaging, and when orally administered causes an influx of fluid into the GI tract resulting in diarrhea[13]. A small CCE study used diatrizoate solution alone as a boost agent and found high rates of adequate colon cleansing and CCE completion, while rapid colonic transit (< 40 min) was rare[14]. A larger study combined diatrizoate solution with NaP as a boost agent and observed adequate colon cleansing in 83%, and CCE completion in 98%, of subjects[15].

This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of a new CCE preparation regimen that combines low dose OSS with diatrizoate solution as a boost agent. The study was conducted at six centers in the United States.

This was a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled study designed to assess the superiority of a new colon cleansing regimen for CCE. Six centers (2 academic) participated, and subjects were enrolled between 5/18/15 and 9/23/15. Each center obtained IRB approval prior to study initiation, and this protocol was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (ID# NCT02481219).

The second generation CCE system (PillCam® COLON 2; Medtronic, Yoqneam, Israel), was used in this study. This consists of an ingestible capsule, sensors attached to the abdominal wall that receive capsule signals, a data recorder, and software (RAPID, version 8.3) enabling image display and creation of reports.

The primary outcome was overall and segmental colon cleansing. Secondary outcomes included polyp detection (≥ 6 mm, ≥ 10 mm, and total), colonic transit time, CCE completion (defined as visualization of the hemorrhoidal plexus), excretion of capsule within 12 h of ingestion, and safety. Colon cleansing was assessed using a validated 4-point grading scale of excellent, good, fair, and poor for individual colon segments and for the overall colon[16]. Adequate cleansing was defined as a combination of good and excellent.

Subjects were asymptomatic and average risk for colorectal cancer (CRC), and ranged in age from 50-75 years. Average risk was defined using the American Gastroenterology Association Guidelines on Colorectal Cancer Screening[17]. Subjects did not have a personal history of CRC or adenoma or inflammatory bowel disease, a first degree family member with CRC under age 60 or two or more first degree relatives with CRC at any age, or a personal or family history of a genetic syndrome high risk for CRC.

Furthermore, subjects were excluded if they had a negative colon evaluation within 5 years (colonoscopy, CTC, flexible sigmoidoscopy, barium enema, or stool testing for blood and/or DNA); a history of GI bleeding, heme positive stool, or iron deficiency; a contraindication to capsule technology including dysphagia or any swallowing disorder, a cardiac pacemaker or implanted electromedical device, anticipation of magnetic resonance imaging within 7 d of capsule ingestion, or increased risk for capsule retention including a suspected or known GI motility disorder, bowel obstruction, stricture or fistula; a history of renal disease; an allergy or contraindication to any component of the study regimens; pregnancy or active breast feeding; participation in another investigational study within 30 d that may interfere with the subject’s safety or ability to participate in this study; a member of a vulnerable population (prisoner, intellectually challenged, etc.); or a severe medical condition such that participation is not appropriate due to increased risk, lack of benefit of screening, or survival anticipated to be less than 6 mo.

Subjects underwent a screening visit to assess eligibility. Demographic information as well as medical and surgical history was obtained, and an assessment of pregnancy potential was performed. Subjects of childbearing potential underwent a urine pregnancy test at the time of screening. During the screening visit, if eligibility criteria were satisfied, informed consent was obtained and subsequently subjects were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive the study bowel preparation regimen (Study) or the comparator control bowel preparation regimen (Control) (see bowel preparation regimen section below and Table 1). This study utilized randomization blocks using a standard envelope procedure. The CCE was performed within 45 days of the screening visit.

| Time | Study regimen | Control regimen |

| 2 d prior | ≥ 2400 mL (10 glasses) of liquid during the day; 4 senna tablets at bedtime | |

| 1 d prior | Clear liquid diet all day; 2 L sulfate-free PEG-ELS1 at about 7-9 pm (one 237 mL-296 mL cup (8-10 oz. cup) every 10-15 min) | |

| Day of capsule procedure | ||

| 45-75 min prior to capsule ingestion | 2 L sulfate-free PEG-ELS | |

| 1 h after capsule ingestion | Optional prokinetics (only if capsule in stomach > 1 h): 10 mg metoclopramide or 250 mg erythromycin | |

| 1st boost: After capsule entry into small bowel2 | 89 mL (3 oz) OSS plus 60 mL diatrizoate solution1 | 89 mL (3 oz.) OSS |

| 2nd boost: 3 h after 1st boost, only if capsule not excreted | 89 mL (3 oz) OSS plus 30 mL diatrizoate solution1 | 89 mL (3 oz.) OSS |

| 3rd boost: 2 h after 2nd boost, only if capsule not excreted | 10 mg bisacodyl suppository | |

| 2 h after 3rd boost, or after capsule passes (whichever occurs first) | Standard full meal |

The CCE videos were read remotely by two readers who had extensive experience reading CCE studies and were unassociated with any study site. Video assignment to centralized readers utilized a 1:1 randomization stratified by bowel preparation group to minimize bias using MDT data manager (Medtronic, Mansfield, MA, United States). Videos were read within 3 wk of CCE completion, and no more than 5 videos per week were read by a single reader.

Readers used the aforementioned four-point scale to grade cleansing for 5 colon segments - cecum, right colon, transverse colon, left colon, and rectum. Additionally, readers provided an overall cleansing grade for the entire colon.

For each polyp, the location and size, as determined by the longest dimension using a software measuring tool, was recorded. The time for the capsule to reach the cecum, hepatic and splenic flexures, and exit the rectum was also measured using software. The cecum and last rectum image was identified by the reader, and then the other colon landmarks were identified by either the software or the reader.

The completed report was provided to the primary investigator at each enrollment site within 3 months of the capsule procedure. Follow-up of capsule findings was left to the discretion of the primary investigator at each site.

The Study and Control bowel preparation regimens are summarized in Table 1. For both regimens, all subjects took 4 senna tablets the evening of Day -2, and 2 L of sulfate-free PEG-ELS (NuLYTELY®, Braintree Laboratories Inc., Braintree, MA, United States) the night before the capsule procedure and again the next morning with completion 45-75 min before capsule ingestion. If the capsule remained in the stomach more than 1 h, subjects in both study arms took metoclopramide 10 mg or erythromycin 250 mg orally.

All subjects (Study and Control) received a 1st boost once the capsule entered the duodenum, and a 2nd boost 3 h later if the capsule had not been excreted. Study and Control regimens differed in the composition of these boosts. For the 1st boost, the Study regimen used 89 mL (3 oz.) of OSS (SUPREP® Braintree Laboratories Inc., Braintree, MA) diluted to 237 mL (8 oz.) with water and 59 mL (2 oz.) of diatrizoate solution (Gastrografin®, Bracco Diagnostics Inc., Monroe Township, NJ, United States) diluted to 207 mL (7 oz.) with water, and for the 2nd boost 89 mL (3 oz.) of OSS diluted to 237 mL (8 oz.) with water and 30 mL (1 oz.) of diatrizoate solution diluted to 89 mL (3 oz.) with water. For both the 1st and 2nd boosts, the Control regimen used 89 mL (3 oz.) of OSS diluted to 237 mL (8 oz.) with water. Subjects in both study arms drank at least 946 mL (32 oz.) of water with the first and second boosts.

Two hours after the 2nd boost, if the capsule had not been excreted, subjects in both study arms received a 3rd boost consisting of a 10 mg bisacodyl suppository. Diet was identical for subjects in both study arms.

Adverse events were recorded throughout the CCE preparation regimen. Subjects were called 5-9 d after completion of the capsule procedure to confirm capsule excretion and record any additional adverse events. Adverse events were classified as serious or non-serious. Non-serious adverse events were characterized and then classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Preparation adequacy, CCE completion, capsule transit times, and polyp detection were compared between the study and control regimens and similar regimens used in two published CCE studies[1,15].The Study regimen was compared to Spada et al[15] as both used the combination of diatrizoate solution and a hyperosmotic purgative for the 1st and 2nd boosts. However, instead of OSS and diatrizoate solution, Spada et al[15]. used NaP in combination with diatrizoate solution [1st boost = 40 mL (1.4 oz.) NaP and 50 mL (1.7 oz.) diatrizoate solution in 1 L (34 oz.) of water; 2nd boost = 25 mL (0.8 oz.) NaP and 25 ml (0.8 oz.) diatrizoate solution in 0.5 L (17 oz.) of water].

The Control regimen was compared to a CCE preparation regimen used by Rex et al[1]. Both regimens were similar except for the OSS dose used for the 1st boost [Control = 89 mL (3 oz.) diluted to 237 mL (8 oz.) plus an additional 946 mL (32 oz.) of water, Rex et al[1] = 177 mL (6 oz.) diluted to 473 mL (16 oz.) plus an additional 946 ml (32 oz.) of water].

Similar to the Study and Control regimens, both Spada et al[15] and Rex et al[1] administered 4 senna tablets two days prior to CCE, split dose 4 L PEG-ELS beginning the night prior to CCE, and a prokinetic agent if the capsule remained in the stomach for more than 1 h.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Mathilde Lourd, a biostatistician from Medtronic Inc.

Primary outcome: A sample size of 500 patients would provide > 80% power to detect a difference between the study groups for overall colon preparation adequacy with a two-sided test at a significance level of 0.05 (adequacy assumptions: 83% Study, 71% Control). Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, was performed to compare proportions of good and excellent cleansing between the two preparation regimens. Non-visualized colon segments were not graded for cleansing and not included in the colon segment preparation grading analysis.

Secondary outcomes: Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used for analyzing polyp detection (≥ 6 mm, ≥ 10 mm, and any polyp) in total for the whole colon and by colon segment, CCE completion rate, adverse events in relation to administration of diatrizoate solution, and colon capsule excretion within 12 h of ingestion. Colon capsule completion was defined as excretion of the capsule within 12 h of ingestion and complete visualization of the colon. t-tests for continuous variables were performed to evaluate the difference between the two preparation regimens for capsule transit time by colon segment and for the entire colon.

Plan for interim analyses: Interim analyses were planned after each group of 50 subjects until a final enrollment of 500. Pre-specified criteria were established for measures of performance and safety that would allow discontinuation of the trial. These included the following: (1) an increased prevalence (> 10%) of polyps (≥ 6 mm and ≥ 10 mm) in the Study group; (2) an increased incidence of adequate (good/excellent) cleansing (> 12%) for the whole colon in the Study group; and (3) adverse events in fewer than 10% of subjects in the Control group.

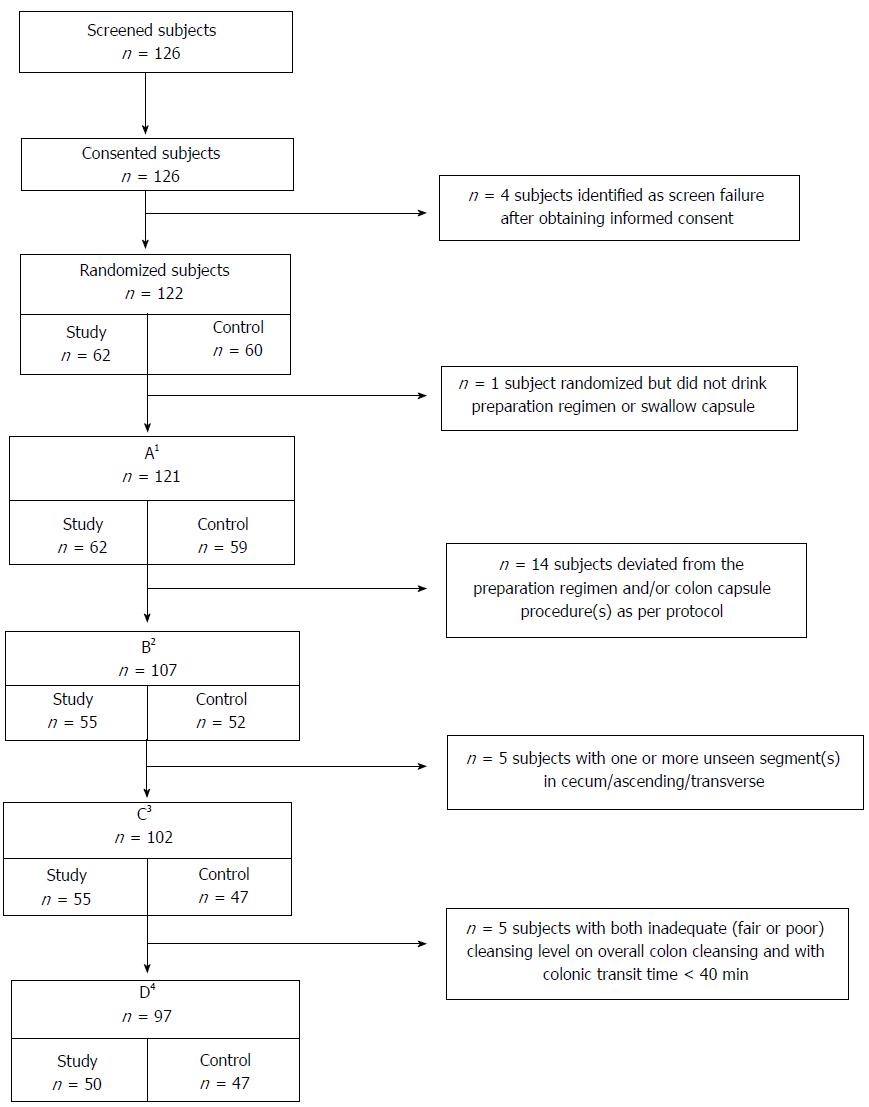

Subject flow is summarized in Figure 1. There were 126 subjects screened and consented, 122 subjects met eligibility criteria, and 121 ingested any of the preparation and were included in the analyses for subject characteristics and safety. After excluding 14 subjects for protocol deviations, 107 were included in the analyses for colon cleansing and polyp detection by colonic segment, CCE completion and transit times, and comparisons between the Control regimen and Rex et al[1]. for colon cleansing by segment. Both study groups were similar with regard to age, gender, and body mass index (BMI) (Table 2).

| Study regimen, n = 62 | Control regimen, n = 59 | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 55.20 | 55.10 | 0.888 |

| Gender (male:female) | 45:55 | 49:51 | 0.660 |

| BMI (mean) | 28.50 | 28.50 | 0.978 |

After excluding 5 additional subjects with ≥ 1 unseen colon segment (cecum, ascending, or transverse), 102 subjects were analyzed for overall colon cleansing, polyp detection for the whole colon, and comparisons between the Study regimen and Spada et al[15] and the Control regimen and Rex et al[1] for overall cleansing of the colon. Five additional subjects were excluded who had both inadequate (fair or poor) overall colon cleansing and colonic transit < 40 min. The exclusions for this final group matched Spada et al[15] and Rex et al[1] to allow comparisons for polyp detection for the whole colon.

The a priori criteria for early termination of this study were met after the first group of 50 subjects. Because enrollment was rapid, by the time the analyses had been completed and the decision to halt the study made, more than 100 subjects were enrolled and the results are presented herein.

For overall colon cleansing, there was no significant difference between the Study and Control regimens using the 4-point scale of excellent, good, fair or poor (Table 3). Overall adequate cleansing (good and excellent combined) of the whole colon was similar for both study groups (Adequate: Study = 75.9%, Control = 77.3%, P = 0.88). When the 4-point scale was used to grade individual colon segments, in no segment was there a significant difference between the Study and Control regimens for any grade (Supplementary Tables 1-4).

| Overall cleansing assessment [95%CI] | Study regimen, n = 55 | Control regimen, n = 52 | P value |

| Adequate1 | 75.9 [62.4; 86.5] | 77.3 [62.2; 88.5] | 0.876 |

| Excellent | 16.7 [7.9; 29.3] | 6.8 [1.4; 18.7] | 0.216 |

| Good | 59.3 [45.0; 72.4] | 70.5 [54.8; 83.2] | 0.243 |

| Fair | 24.1 [13.5; 37.6] | 22.7 [11.5; 37.8] | 0.875 |

| Poor | 0.0 [0.0; 5.9] | 0.0 [0.0; 6.6] | -- |

| Polyp size [95%CI] | Study regimen, n = 55 | Control regimen, n = 52 | P value |

| ≥ 6 mm | 36.4 [23.8; 50.4] | 21.3 [10.7; 35.7] | 0.096 |

| ≥ 10 mm | 14.6 [6.5; 26.7] | 8.5 [2.4; 20.4] | 0.346 |

| Any polyp | 58.2 [44.1; 71.3] | 46.8 [32.1; 61.9] | 0.251 |

Table 4 summarizes overall polyp detection for both study groups. There was a trend toward higher polyp detection for the whole colon with the Study regimen, although this was not statistically significant for any size category. When evaluated by colon segment, detection of polyps of all sizes (≥ 6 mm, ≥ 10 mm, and any polyp) was not significantly different between the Study and Control regimens (Supplementary Tables 5-7).

| Study regimen, n = 55 | Control regimen, n = 52 | P value | |

| CCE completion [95%CI] | 90.9 [80.0; 97.0] | 76.9 [63.2; 87.5] | 0.0482 |

| CCE excretion ≤ 12 h [95%CI] | 90.9 [80.0; 97.0] | 80.4 [66.9; 90.2] | 0.121 |

| GI tract transit - Ingestion to excretion1, mean (SD) [95%CI] | 5:54 (6:00) [4:18; 7:30] | 9:00 (11:48) [5:36; 12:24] | 0.107 |

| Colonic transit time1, mean (SD) [95%CI] | 2:12 (1:36) [1:48; 2:42] | 2:36 (1:30) [2:06; 3:06] | 0.262 |

| Colonic Transit < 40 min [95%CI] | 21.8 [11.8; 35.0] | 4.0 [0.5; 13.7] | 0.0072 |

| Adverse event | Study regimen, n = 62 | Control regimen, n = 59 | P value |

| Subjects with ≥ 1, n (%) [95%CI] | 12 (19.4) [10.4; 31.4] | 2 (3.4) [0.4; 11.7] | 0.0062 |

| Occurring in > 2% of subjects, n (%) [95%CI] | |||

| Headache | 2 (3.2) [0.4; 11.2] | 1 (1.7) [0.0; 9.1] | |

| Nausea | 4 (6.5) [1.8; 15.7] | 2 (3.4) [0.4; 11.7] | |

| Vomiting | 2 (3.2) [0.2; 38.5] | 0 (0) [0.0; 77.6] | |

| Maximum AE severity1, n (%) [95%CI] | |||

| Mild | 6 (50) [21.1; 78.9] | 2 (100) [22.4; 100.0] | |

| Moderate | 5 (41.7) [15.2; 72.3] | 0 (0) [0.0; 77.6] | 0.308 |

| Severe | 1 (8.3) [0.2; 38.5] | 0 (0) [0.0; 77.6] |

| Parameter | Study regimen | Spada et al (4)1 | P value |

| Adequate preparation-whole colon (% [95%CI]) | 75.9 [62.4; 86.5] | 78.0[64.0; 88.5] | 0.820 |

| CCE completion (% [95%CI]) | 90.2 [79.8; 96.3] | 96.0 [86.3; 99.5] | 0.291 |

| GI transit time2, mean (SD) [95%CI] | 6:00 (6:12) [4:24; 7:36] | 6:06 (4:48) [4:46; 7:26] | 0.925 |

| Polyp detection (% [95%CI]) | |||

| ≥ 6 mm | 36.0 [22.9; 50.8] | 25.0 [13.6; 39.6] | 0.233 |

| ≥ 10 mm | 16.0 [7.2; 29.1] | 12.5 [4.7; 25.2] | 0.619 |

Colon capsule completion and transit times are summarized in Table 5. Superior completion of the CCE procedure was achieved with the Study regimen (Study = 90.9%, Control = 76.9%; P = 0.048). Mean transit time through the entire GI tract, from ingestion to excretion, was shorter with the Study regimen while mean colonic transit times were similar for both study groups. Significantly more Study regimen subjects experienced capsule transit through the colon in less than 40 min (Study = 21.8%; Control = 4%, P = 0.007). Five subjects (9%) in the Study regimen arm had both inadequate colon cleansing and colonic transit < 40 min.

Adverse events occurred more often in subjects receiving the Study regimen [Study = 12 (19.4%), Control = 2 (3.4%); P = 0.0061], and these were primarily related to bowel preparation [Study = 8 (12.9%), Control = 1 (1.7%); P = 0.0327] and were gastrointestinal in nature (Table 6). The incidence of adverse events in Study regimen subjects was similar before and after administration of diatrizoate solution (before diatrizoate solution = 9.7%, after diatrizoate solution = 6.5%; P = 0.4142.) One serious adverse event occurred with the Study regimen (sinusitis), and this was judged unrelated to the preparation regimen or the capsule procedure. All adverse events in the Control regimen arm were graded as mild, and there was a non-significant trend toward a higher level of adverse event severity experienced by Study regimen subjects (Table 6).

Study regimen: The Study regimen demonstrated no significant difference as compared to Spada et al[15] for overall cleansing of whole colon, CCE completion, capsule transit through the entire GI tract, and overall polyp detection (Table 7).

Control regimen: The Control and Rex et al[1] regimens had similar overall cleansing efficacy for the whole colon and for individual colon segments. However, the Control regimen had a significantly lower rate of completion (Control = 77.6%, Rex et al[1] = 89%; P = 0.041) and a longer mean colonic transit time (Control = 2 h 48 min, Rex et al[1] = 1 h 52 min; P < 0.001). Polyp detection was not significantly different between the two regimens, but there was a trend toward higher detection for polyps ≥ 6 mm with the Rex et al[1] bowel preparation regimen (Table 8).

| Parameter | Control regimen | Rex et al (7)1 | P value |

| Adequate preparation–whole colon (% [95%CI]) | 77.3 [62.2; 88.5] | 71.4 [68.1; 74.5] | 0.369 |

| CCE completion (% [95%CI]) | 77.6 [64.7; 87.5] | 89.0 [86.8; 91.0] | 0.0413 |

| GI transit time2, mean (SD) [95%CI] | 2:48(1:36) [2:18; 3:18] | 1:52 (1:40) [1:45; 1:59] | < 0.0013 |

| Polyp detection (% [95%CI]) | |||

| ≥ 6 mm | 21.3 [10.7; 35.7] | 31.5 [28.1; 35.1] | 0.100 |

| ≥ 10 mm | 8.5 [2.4; 20.4] | 11.4 [9.1; 14.0] | 0.810 |

A new CCE preparation regimen using OSS + diatrizoate as a boost agent did not improve colon cleansing as compared to low dose OSS alone. The OSS + diatrizoate regimen resulted in more rapid transit of the capsule with a trend toward faster transit through the entire GI tract, superior CCE completion, and more frequent colonic transit less than 40 min. There was also a trend toward higher polyp detection with OSS + diatrizoate. More subjects receiving OSS + diatrizoate experienced adverse events which were primarily related to the bowel regimen and GI in nature, but did not appear to be related to diatrizoate solution. Patient related factors, not identified in this study, may have accounted for this difference in adverse events between the Study and Control arms.

The combination of a hyperosmotic colon purgative (NaP) and hyperosmotic diatrizoate solution for use as a boost agent has previously been shown to be effective[15]. The study reported herein evaluated the use of OSS as an alternative hyperosmotic colon purgative. As a boost agent, OSS + diatrizoate performed similarly to the combination of NaP and diatrizoate solution with respect to colon cleansing adequacy, CCE completion, overall GI transit time, and polyp detection. While these results support OSS as a boost agent in place of NaP, use of a historical comparator is a limitation.

A large prospective CCE study by Rex et al[1] found an unexpectedly high number of capsule studies (approximately 10%) could not be evaluated due to a combination of inadequate preparation and rapid (< 40 min) colonic transit. A similar frequency (approximately 9%) of CCE studies with both inadequate cleansing and colon transit < 40 min was observed with the Study regimen. It is unknown whether this trend would have continued had enrollment not been terminated early. Our Control regimen differed from Rex et al[1] only in the OSS dose for the 1st boost [Control = 89 mL (3 oz.), Rex et al[1] = 177 mL [6 oz.)]. As compared to Rex et al[1] boosts comprised of low dose OSS alone did slow transit but at a cost of inferior CCE completion. These data suggest that while CCE transit is too often fast with the Rex et al[1]. regimen, transit may be too slow when the 1st and 2nd boost utilize low dose OSS alone [1]. Again, these conclusions are limited by the use of a historical comparator.

Like colonoscopy, CCE’s effectiveness depends on a complete colon exam and adequate preparation. Achieving these endpoints with colon capsule is a complicated endeavor in that the preparation regimen must both cleanse the colon and propel the capsule. The lumen must be fluid filled and clear of debris, and the capsule needs to traverse the entire colon within the limits of its battery life - but not too quickly such that findings could be missed. And, just like colonoscopy, complete passage through the colon and adequate preparation are basic requirements and no guarantee that lesions will not be missed. Using colonoscopy as the gold standard, a meta-analysis showed that the second-generation colon capsule utilized in our study had high sensitivity and specificity for polyps ≥ 6 mm[18]. The acceptable standards for CCE completion and adequate bowel preparation remain to be determined, but it is reasonable to believe that higher thresholds will translate into better outcomes.

Our study has some additional limitations. While enrollment was terminated early using pre-specified criteria, outcomes may have varied if full enrollment was achieved. While the difference between the Study and Control regimens for polyp detection seen after the first interim analysis at 50 subjects persisted after enrollment closed, this was not the case for preparation adequacy or adverse event incidence. Colon cleansing was graded per segment and overall (primary endpoint), but a preparation receiving an overall grade of adequate could have one or more individual segments graded as graded as fair or poor. Looking to colonoscopy and the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale for guidance, a total colon score of > 5 is associated with both superior polyp detection and high adherence to guidelines for screening and surveillance[19]. Yet, individual colon segment scores are important, and segments scored < 2 are at greater risk for missing polyps[20]. For colon capsule, whether an overall cleansing grade of adequate is sufficient for quality measures such as polyp detection and compliance with interval performance of this procedure remains to be determined. Finally, in the study we have presented, polyp detection by CCE was not confirmed with colonoscopy. However, a meta-analysis demonstrating high sensitivity and specificity for polyps ≥ 6 mm and ≥ 10 mm with the colon capsule utilized for this study provides reassurance regarding its accuracy for polyp detection[18].

In summary, a CCE preparation regimen combining two hyperosmotic agents, OSS and diatrizoate solution, as a boost agent was not superior to low dose OSS alone for achieving adequate overall colon cleansing. The OSS + diatrizoate regimen did achieve a high rate of colon capsule completion, was associated with trend toward higher polyp detection, and performed similarly to a historic comparator boost regimen comprised NaP + diatrizoate. The combination of inadequate preparation and rapid colonic transit seen in some subjects receiving OSS + diatrizoate, which may lower the accuracy of CCE, is a potential limitation of this regimen and requires additional investigation. Future research efforts should continue to focus on improving cleansing efficacy and patient tolerance while maintaining high rates of colon capsule completion. While permitting sufficient capsule dwell time in the colon is important to minimize the risk for missing lesions, the effect of rapid colonic transit may be mitigated with adequate cleansing.

The technical performance of colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) has made great strides, but this technology remains highly dependent on the purgative procedure. The ideal capsule preparation would (1) adequately cleanse the colon; (2) propel the capsule through the GI tract within its battery life; (3) enable sufficient dwell time within the colon for accurate visualization; (4) be tolerable and safe; (5) be easily generalizable for the vast majority of patients. Each of these areas require improvement, and this study’s significance is that it moves this field forward by evaluating a new boost agent.

Tailoring the preparation procedure based on patient characteristics and real-time capsule feedback (“personalized” medicine) will likely improve CCE performance, tolerability, safety, and subsequently acceptance. Technological advancements that reliably visualize mucosa obscured by debris, and assist in the detection of polyps, would be immensely helpful as well.

The main objective was to evaluate the efficacy of new boost agent consisting of low dose sulfate solution combined with diatrizoate solution (“Study” regimen), and comparing this to low dose sulfate solution alone (“Control” regimen). We found that colon cleansing was similar between the two regimens, but CCE completion and the proportion of subjects in which the capsule passed through the colon in less than 40 min were significantly greater with the Study regimen. Also observed was numerically greater, not statistically superior, polyp detection with the Study regimen. This suggests that it is reasonable to incorporate the boost regimen of low dose sulfate solution and diatrizoate solution into the preparation procedure for CCE.

This was a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled study comparing two preparation regimens for CCE at six United States sites, 2 of which were academic centers. CCE studies were read centrally by experienced readers who were blinded to subject randomization, and a validated cleansing scale for CCE was utilized.

The study regimen did not result in superior colon cleansing, but did result in a superior rate of CCE completion and higher proportion of studies with colonic transit less than 40 min. Increased polyp detection, though not significant, was observed in the Study arm suggesting that polyp detection was not compromised in this group. However, this study was not powered for polyp detection. We also observed a greater incidence of adverse events, primarily GI, in the Study group. This observation in the Study group did not appear to be related to the boost agent. Progress needs to be made in further improving the efficacy of colon cleansing, with the goal for CCE being more closely aligned with that established for traditional colonoscopy. Further, simplifying the regimen, shortening overall GI transit time, and lessening the incidence of adverse events related to the preparation regimen are all worthy of further study.

Diatrizoate solution augments the performance of sulfate solution to create an effective and very low dose hyperosmotic boost agent for CCE. The combination of low dose sulfate solution and diatrizoate solution was superior to low dose sulfate solution alone with respect to CCE completion and the frequency that the capsule traversed the colon in less than 40 minutes. These findings, along with a trend toward higher polyp detection with the combination Study regimen, support the use of low dose sulfate solution combined with diatrizoate solution as a boost agent in place of low dose sulfate solution alone.

While our findings represent an improvement in the preparation regimen for CCE, there is still much progress to be made in this arena. In particular, the rate of preparation adequacy needs to increase. Personalized medicine may play a role in optimizing the regimen for CCE. Using patient characteristics and real time capsule data, individual adjustments might include varying the volume of PEG-ELS, utilizing additional agents, adjusting the frequency and timing of medication administration, and more.

| 1. | Rex DK, Adler SN, Aisenberg J, Burch WC Jr, Carretero C, Chowers Y, Fein SA, Fern SE, Fernandez-Urien Sainz I, Fich A, Gal E, Horlander JC Sr, Isaacs KL, Kariv R, Lahat A, Leung WK, Malik PR, Morgan D, Papageorgiou N, Romeo DP, Shah SS, Waterman M. Accuracy of capsule colonoscopy in detecting colorectal polyps in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:948-957.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Eliakim R, Yassin K, Niv Y, Metzger Y, Lachter J, Gal E, Sapoznikov B, Konikoff F, Leichtmann G, Fireman Z. Prospective multicenter performance evaluation of the second-generation colon capsule compared with colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:1026-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Spada C, Hassan C, Munoz-Navas M, Neuhaus H, Deviere J, Fockens P, Coron E, Gay G, Toth E, Riccioni ME. Second-generation colon capsule endoscopy compared with colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:581-589.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Eliakim R, Fireman Z, Gralnek IM, Yassin K, Waterman M, Kopelman Y, Lachter J, Koslowsky B, Adler SN. Evaluation of the PillCam Colon capsule in the detection of colonic pathology: results of the first multicenter, prospective, comparative study. Endoscopy. 2006;38:963-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schoofs N, Devière J, Van Gossum A. PillCam colon capsule endoscopy compared with colonoscopy for colorectal tumor diagnosis: a prospective pilot study. Endoscopy. 2006;38:971-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Van Gossum A, Munoz-Navas M, Fernandez-Urien I, Carretero C, Gay G, Delvaux M, Lapalus MG, Ponchon T, Neuhaus H, Philipper M. Capsule endoscopy versus colonoscopy for the detection of polyps and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:264-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sacher-Huvelin S, Coron E, Gaudric M, Planche L, Benamouzig R, Maunoury V, Filoche B, Frédéric M, Saurin JC, Subtil C. Colon capsule endoscopy vs. colonoscopy in patients at average or increased risk of colorectal cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1145-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pilz JB, Portmann S, Peter S, Beglinger C, Degen L. Colon Capsule Endoscopy compared to Conventional Colonoscopy under routine screening conditions. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Spada C, Riccioni ME, Hassan C, Petruzziello L, Cesaro P, Costamagna G. PillCam colon capsule endoscopy: a prospective, randomized trial comparing two regimens of preparation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:119-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rondonotti E, Borghi C, Mandelli G, Radaelli F, Paggi S, Amato A, Imperiali G, Terreni N, Lenoci N, Terruzzi V. Accuracy of capsule colonoscopy and computed tomographic colonography in individuals with positive results from the fecal occult blood test. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1303-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Desmeules S, Bergeron MJ, Isenring P. Acute phosphate nephropathy and renal failure. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1006-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Markowitz GS, Nasr SH, Klein P, Anderson H, Stack JI, Alterman L, Price B, Radhakrishnan J, D’Agati VD. Renal failure due to acute nephrocalcinosis following oral sodium phosphate bowel cleansing. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:675-684. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Borthne AS, Dormagen JB, Gjesdal KI, Storaas T, Lygren I, Geitung JT. Bowel MR imaging with oral Gastrografin: an experimental study with healthy volunteers. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:100-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Togashi K, Fujita T, Utano K, Waga E, Katsuki S, Isohata N, Endo S, Lefor AK. Gastrografin as an alternative booster to sodium phosphate in colon capsule endoscopy: safety and efficacy pilot study. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E659-E661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Spada C, Hassan C, Barbaro B, Iafrate F, Cesaro P, Petruzziello L, Minelli Grazioli L, Senore C, Brizi G, Costamagna I. Colon capsule versus CT colonography in patients with incomplete colonoscopy: a prospective, comparative trial. Gut. 2015;64:272-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Leighton JA, Rex DK. A grading scale to evaluate colon cleansing for the PillCam COLON capsule: a reliability study. Endoscopy. 2011;43:123-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond J, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Johnson D. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1423] [Cited by in RCA: 1461] [Article Influence: 81.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Spada C, Pasha SF, Gross SA, Leighton JA, Schnoll-Sussman F, Correale L, González Suárez B, Costamagna G, Hassan C. Accuracy of First- and Second-Generation Colon Capsules in Endoscopic Detection of Colorectal Polyps: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1533-1543.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 930] [Cited by in RCA: 991] [Article Influence: 58.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Clark BT, Protiva P, Nagar A, Imaeda A, Ciarleglio MM, Deng Y, Laine L. Quantification of Adequate Bowel Preparation for Screening or Surveillance Colonoscopy in Men. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:396-405; quiz e14-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Hauser G, Lorenzo-Zuniga V, Stanciu C S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y