Published online Dec 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i48.8605

Peer-review started: August 31, 2017

First decision: September 13, 2017

Revised: September 27, 2017

Accepted: October 18, 2017

Article in press: October 18, 2017

Published online: December 28, 2017

Processing time: 119 Days and 5.8 Hours

To describe the development and implementation of a person-centered endoscopy safety checklist and to evaluate the effects of a “checklist intervention”.

The checklist, based on previously published safety checklists, was developed and locally adapted, taking patient safety aspects into consideration and using a person-centered approach. This novel checklist was introduced to the staff of an endoscopy unit at a Stockholm University Hospital during half-day seminars and team training sessions. Structured observations of the endoscopy team’s performance were conducted before and after the introduction of the checklist. In addition, questionnaires focusing on patient participation, collaboration climate, and patient safety issues were collected from patients and staff.

A person-centered safety checklist was developed and introduced by a multi-professional group in the endoscopy unit. A statistically significant increase in accurate patient identity verification by the physicians was noted (from 0% at baseline to 87% after 10 mo, P < 0.001), and remained high among nurses (93% at baseline vs 96% after 10 mo, P = nonsignificant). Observations indicated that the professional staff made frequent attempts to use the checklist, but compliance was suboptimal: All items in the observed nurse-led “summaries” were included in 56% of these interactions, and physicians participated by directly facing the patient in 50% of the interactions. On the questionnaires administered to the staff, items regarding collaboration and the importance of patient participation were rated more highly after the introduction of the checklist, but this did not result in statistical significance (P = 0.07/P = 0.08). The patients rated almost all items as very high both before and after the introduction of the checklist; hence, no statistical difference was noted.

The intervention led to increased patient identity verification by physicians - a patient safety improvement. Clear evidence of enhanced person-centeredness or team work was not found.

Core tip: With increasing indications and more technically advanced gastrointestinal endoscopy, finding strategies to prevent adverse events is important. Standardized methods, such as checklists and promoting patient involvement, are strategies for augmented patient safety. This paper describes the development of a novel endoscopy checklist that combined patient safety and a person-centeredness approach. After the introduction of the checklist, physicians’ verifications of patients’ identities before their examinations increased significantly. However, compliance to the checklist was suboptimal, possibly due to insufficient training. With more team training for all staff members, the checklist could be a tool for increased person-centeredness and safety.

- Citation: Dubois H, Schmidt PT, Creutzfeldt J, Bergenmar M. Person-centered endoscopy safety checklist: Development, implementation, and evaluation. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(48): 8605-8614

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i48/8605.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i48.8605

In 1999, the United States Institute of Medicine (IOM) published the report “To Err is Human”[1], which raised awareness of major flaws in the American healthcare system and called for increased patient safety. In 2015, almost two decades later, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare[2] estimated that one in ten hospital patients suffered harm due to adverse events during their stay. Therefore, it is clear that this is an ongoing issue and that healthcare professionals worldwide are still seeking strategies to prevent mistakes being made in patient care and to improve their facilities’ cultures of safety.

Indications for gastrointestinal endoscopy are increasing, and endoscopic examinations are becoming more technically advanced. However, possible complications during endoscopy procedures still include cardiopulmonary complications, sedation-related complications, allergic reactions, perforation, and bleeding[3,4]. Knowledge about a patient’s health condition and proper monitoring of his or her vital functions are crucial to assess risks and prevent adverse events[3,4]. In addition, patient misidentification is a known safety risk[5,6] to which endoscopy teams should give special consideration as endoscopy is often a high-volume service.

One of the most well-known improvements of patient safety using standardized methods was the release of the World Health Organization’s Surgical Safety Checklist in 2009 (WHO SSC)[7], which has been shown to contribute to improved surgical outcomes[8]. Improved communication in surgical teams, a factor known to be associated with improved patient outcomes[9], was another positive effect of the WHO SSC[10,11]. However, compliance with the WHO SSC varies widely among hospitals[12-14]. In a study by Conley et al[15] the quality of implementation was an important factor in the effectiveness of the checklist. In addition, “explaining why” and “showing how” were of great importance in motivating checklist use. Matharoo et al. came to a similar conclusion when assessing compliance to a checklist used in an endoscopy unit in the United Kingdom; they recommended that adherence to the checklist could be better maintained by continued re-assessment and feedback[16].

Another method for improving healthcare quality is promoting patient participation. In a systematic review, McMillan et al[17] found that a patient-centered model seemed to increase patient satisfaction and their perceived quality of health. In addition, Greene et al[18] found a relationship between patient activation and positive health-related outcomes. Indeed, patient participation has been recognized as one of the key factors to patient safety[19,20]; therefore, healthcare professionals working directly with patients need training in facilitating patient participation and creating an open and safety-focused culture[21].

Person-centered care (PCC) views the patient as an accountable and capable individual who is an expert on his/her own condition. This approach to care emphasizes patient participation and empowerment[22]. One view of PCC is that the patient and the healthcare professionals should establish a partnership where the patient narrative - the personal account of the patient’s life situation and illness - is given key importance for shared decision making[23]. Despite the lack of a universal definition of PCC in the literature, it has been described as a collaborative and respectful partnership between healthcare professionals and the patient, including information exchange with both parts actively involved in the planning and the delivery of care with shared specified goals and strategies[24].

The aim of this study was twofold: Firstly, to describe the development and implementation of an endoscopy checklist at an inpatient and outpatient endoscopy unit that combined safety and person-centeredness, and secondly, to evaluate this “checklist intervention” in terms of patient safety, person-centeredness, and teamwork.

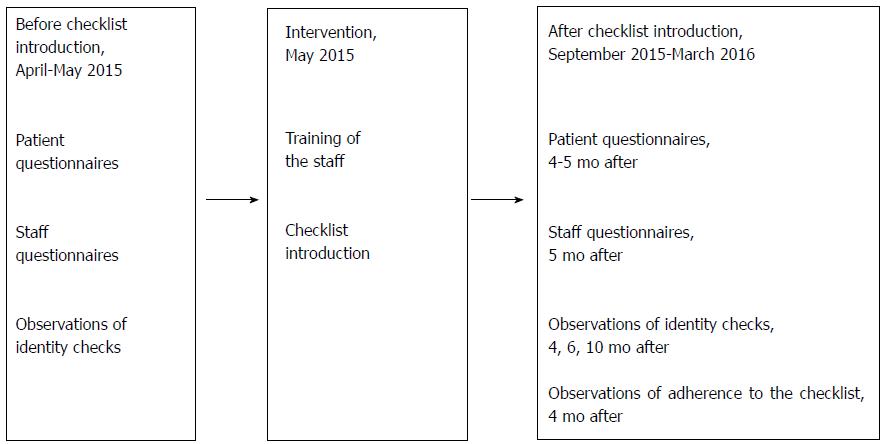

The study was conducted in one of two endoscopy units at the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden, as a part of a quality improvement project. At the unit, approximately 5000 endoscopic examinations are conducted each year. At the time of the study, ten nurses were employed at the unit (including the first author). Approximately 30 different physicians worked at the unit in varying degrees of frequency. The study design is presented in Figure 1.

The checklist was developed by a multi-professional group consisting of endoscopy nurses, senior physicians, and experts in person-centered care and teamwork. The WHO SSC[7] and the only endoscopy safety checklist found in the current literature and available at the time[25] were reviewed. Items considered relevant for endoscopy and of high impact for patient safety (i.e., those that were in line with the hospital’s incident reporting system) were incorporated into the endoscopy checklist. Local safety issues and routines were also taken into consideration. However, none of the reviewed checklists involved the patient; thus, a person-centered focus was introduced.

The implementation of the checklist was thoroughly planned and included factors identified as “enablers” to checklist uptake (i.e., to explain why and show how)[15]. The project was supported by local management, and attendance at the checklist introduction seminars and team training sessions was mandatory for all endoscopy staff.

The checklist was introduced to the staff during three half-day sessions in multi-professional groups of five to seven members in May 2015. The sessions included oral presentations on safety culture, person-centered care, and the new checklist, which was illustrated with a short motivational instruction film. Scenario-based team training was then overseen by instructors from the hospital’s Center for Advanced Medical Simulation and Training. The training focused on compliance to the checklist, non-verbal communication such as body language, and addressing the patient during the “summary” to enhance person-centeredness. Group discussions followed each training session.

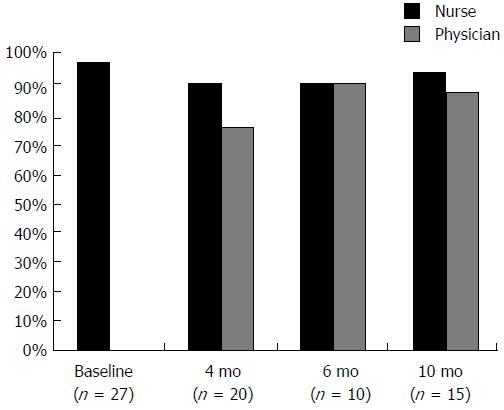

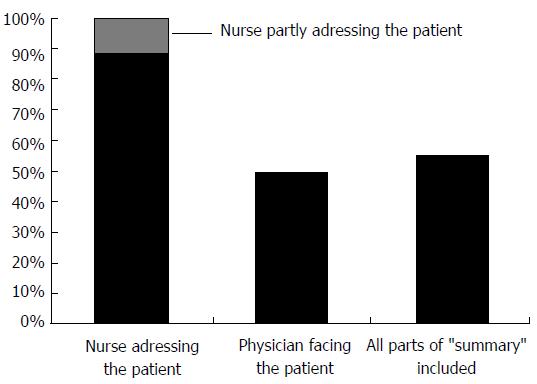

The identity verifications of patients (i.e., checking a patient’s identity number against his or her medical record) performed by the nurses and physicians before an endoscopy were observed at baseline and at 4, 6, and 10 mo after the checklist was introduced. Staff were regularly informed that quality improvement observations were going to be performed but not told explicitly what was being observed or when the observations would take place. The observations were performed by the first author or by a research nurse who was in the examination room for other purposes. At 4 mo after the checklist intervention, adherence to the checklist was also observed using a standardized protocol, with a focus on the “summary” since it incorporated both safety issues and a person-centered approach. One of the purposes of the “summary” observations was to monitor if the staff addressed the patient and directly looked at him or her (Figure 2). The teams observed consisted of at least one physician and one nurse. The observations were performed on random days, with the ambition of observing as many different physician-nurse combinations as possible.

An 18-item patient questionnaire was developed; its face validity was tested with patients (n = 10), revisions were made, and then a final version was implemented. It included questions regarding (1) information (about the procedure and findings); (2) patient participation; (3) identity check; (4) staff’s behavior toward the patient; (5) perception of safety; (6) repeated questions from staff members; and (7) the perception of teamwork and safety measures within the medical team.

For 12 of the items, the response format was a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Six questions had the response options of “yes,” “no,” or “partly/don’t remember.”

After their endoscopic examination, patients were asked if they would be part of the study and informed, both verbally and in writing, that the participation was voluntary and anonymous. The inclusion criteria for patients receiving a questionnaire were that they were older than 18 years and fluent in Swedish. Exclusion criteria were the following: (1) patients unable to fill out the questionnaire due to cognitive failure, poor general condition, or heavy sedation; (2) patients who had already filled out the questionnaire in the past month; and (3) patients who had already been examined during the observations of the first author were excluded from completing the questionnaire to rule out the risk of influence on patient experiences. Nurses working in the unit collected the questionnaires at the very end of the patients’ visits.

Prior to the introduction of the checklist, a baseline questionnaire was distributed to both inpatients and outpatients at the endoscopy unit over a 7-d period. In September to October 2015, patient questionnaires were randomly collected again.

In addition, a 14-item staff questionnaire contained questions/statements regarding (1) team collaboration; (2) working climate; (3) patient participation; and (4) patient safety. Items were partly adopted and incorporated from the validated Safety Attitudes Questionnaire[26]. The staff questionnaire was developed and tested in two steps: first by its face validity on the physicians (n = 3) and nurses (n = 2) at the hospital’s other endoscopy unit and then revising and testing through a test-retest process using physicians (n = 5) and nurses (n = 5) at the “twin unit.” No need to further revise the questionnaire was found.

Staff was informed that their contributions via the questionnaire were voluntary and anonymous. Inclusion criteria for the staff questionnaire were that they worked at least 4 shifts per year in the unit and were fluent in Swedish. One nurse endoscopist at the unit was excluded from completing the questionnaire since she would not be able to participate anonymously. The baseline questionnaire was collected a few weeks prior to the intervention start, and the follow-up questionnaire was collected 5 months after the start of the intervention.

Observations: The frequency of identity checks performed by the nurses and the physicians was compared before and 10 months after the “checklist intervention” using the Fischer’s exact test.

Patient questionnaires: Data are presented as medians and 25-75 percentiles. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to test for statistically significant differences before and after the intervention. For the dichotomous responses, Fischer’s exact test and χ2, when appropriate, were used. The frequencies and proportions of responses to the questionnaires were calculated including only the response alternatives “Yes” or “No”.

Staff questionnaires: Data are presented as medians and 25-75 percentiles. The Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed-ranks test was used to test for statistically significant differences before and after the intervention. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

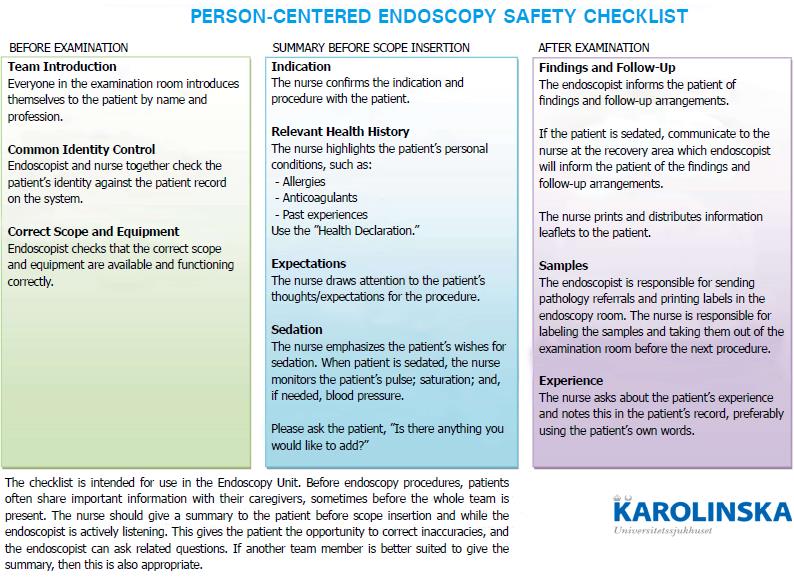

In the final checklist, the patients’ individual conditions, experiences, expectations, and/or fears were highlighted in addition to safety-related items. Most importantly, the “summary,” which corresponded to the “timeout” in the WHO SSC, directly addressed the patient before scope insertion was performed, giving him or her an opportunity to correct any inaccuracies. This “summary” always preceded any sedation of the patient and was performed by the nurse/endoscopy assistant who had followed the patient from the onset of the visit. The physician participated by first actively listening to the “summary” and then, if necessary, posing additional questions. The summary was ended by asking the patient if he or she had questions or wanted to add anything.

The checklist was displayed on large posters on the walls in all examination rooms; they were therefore visible to both the medical teams and the patients. In Figure 2, an English translation of the checklist is presented.

All nurses in the unit (n = 9), including the nurse endoscopist, attended the checklist introduction training. Out of the 20 physicians scheduled in the endoscopy department during the study period, seven participated in the training and two at attended an open lunch seminar. The remaining 11 physicians were briefed on the checklist by the first author and/or by viewing the instruction film.

During the baseline observations (n = 27), none of the physicians performed identity checks, while nurses did so for 96% of the observations. Follow-up observations (n = 45) were performed at 4, 6, and 10 mo after the intervention. The rate of identity checks for both the physicians and nurses remained high during the study period, reaching 87% at 10 mon (P < 0.001) for the physicians and 93% for the nurses (P = n.s.). Observations regarding the identity verifications are illustrated in Figure 3.

At 4 mo after the introduction of the checklist, a “summary” was initiated for 18 of 20 of the observations (90%) but with a varying degree of completeness (Figure 4). All parts of the “summary” box were included in 56% of the observations. The nurses fully addressed the patients during the “summaries” 89% of the time and partly addressed the patient 11% of the time. The physicians faced the patients 50% of the observed “summaries.”

Out of 168 patients examined during the baseline data collection period, 104 patients (62 %) completed the questionnaires. Reasons for not completing the questionnaires were the following: (1) The patient did not meet the criteria; (2) the patient declined to participate; or (3) the patient did not receive the questionnaire due to a heavier-than-normal workload for the nurses. At baseline data are missing regarding the number of patients per reason not to participate. During the follow-up, 183 patients were examined at the unit. Questionnaires were distributed to 141 patients; 42 patients did not receive the questionnaires due to a heavier-than-normal workload for the nurses collecting questionnaires. Out of the 141 patients, 30 did not meet the study criteria, leaving a sample of 111. Eleven patients declined participation. Completed questionnaires were received from 100 patients. Thus, the response rate was 55% if calculated according to the baseline and 90% if calculated based on eligible patients who received a questionnaire. Patient background factors are shown in Table 1. Missing values are not presented.

| Baseline questionnaire,n = 104 | Follow-up questionnaire,n = 100 | |

| Men | 49 (47) | 38 (38) |

| Women | 50 (48) | 57 (57) |

| Age 18-29 yr | 7 (7) | 7 (7) |

| Age 30-64 yr | 62 (60) | 52 (52) |

| Age > 64 yr | 34 (33) | 37 (37) |

| Inpatients | 10 (10) | 17 (17) |

On the patient questionnaire, both at baseline and at follow-up, all Likert-scale ratings were 7 in median. The 25-75 percentiles were 7-7 for all responses but one, where it was 6-7. Data from these statements in the questionnaire are not presented further. The proportions (%) of patients’ responses to the questions with the response options of “yes” or “no” are presented in Table 2.

| Baseline questionnaire,n = 104 Yes/No(% Yes) | Follow-up questionnaire, n = 100 Yes/No(% Yes) | P value | |

| I was offered sedatives before my examination | 97/2 (98%) | 95/2 (98%) | NS |

| I was given sedatives and/or analgesic drugs during my examination | 77/26 (75%) | 75/23 (76%) | NS |

| I was asked by the staff in the examination room to state my social security number/show identification | 96/6 (94%) | 97/1 (99%) | NS |

| I had to answer the same questions several times while I was in the examination room | 29/49 (37%) | 47/33 (59%) | 0.011 |

| I received information concerning the result of the examination/treatment | 74/5 (94%) | 81/6 (93%) | NS |

| The nurse asked me how I experienced the examination | 79/7 (92%) | 79/7 (92%) | NS |

The baseline staff questionnaire was distributed to nurses (n = 8) and physicians (n = 20) a few weeks prior to the intervention. The follow-up staff questionnaire was distributed 5 mo after the checklist introduction to the nurses (n = 8) and physicians (n = 18) who were eligible for inclusion at that time. The response rate for the nurses was 100% both before and after the implementation. All nurses were women. The response rate for the physicians was 65% (n = 13) at baseline and 72% (n = 13) in the follow-up period. Among physicians at the baseline, 3 respondents were women and 10 were male; at the follow-up, 2 physicians were women, 10 were men, and 1 did not report his or her gender. The staff questionnaire is presented in Table 3. No significant differences were found between the nurses’ and physicians’ answers; thus, they are presented together. In 2 of the 14 questions the changes were close to reaching statistical significance; i.e., there were signs of increased quality in collaboration with nurses (P = 0.07) and an increased perception of the importance of patient participation (P = 0.08) after checklist implementation.

| All Staff (Physicians and Nurses) | P value | ||

| Baseline,n = 21 (Nurses n = 8,Physicians n = 13) | Follow-Up,n = 21 (Nurses n = 8, Physicians n = 13) | ||

| Response options on a 7-point Likert-type scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree | Median (25-75 percentiles) | ||

| The doctors and nurses work together as a well-coordinated team at the endoscopy unit | 5 (4-6) | 6 (6-7) | NS |

| I know the staff I worked with during my most recent shift at the endoscopy unit by first and last name | 6 (3.5-7) | 7 (3.25-7) | NS |

| Patient participation is considered important at the endoscopy unit | 5 (5-6.5) | 7 (6-7) | P = NS (0.08) |

| Patient safety is considered important at the endoscopy unit | 7 (6-7) | 7 (6-7) | NS |

| It is easy for patients to ask the staff questions at the endoscopy unit if there is something they do not understand | 6 (5-6) | 6 (5-7) | NS |

| It is easy for the staff to ask each other questions if there is something they do not understand | 5.5 (5-7) | 6 (5-7) | NS |

| We have clear routines for working in a patient-safe manner at the endoscopy unit | 5 (4-6.5) | 6 (6-7) | NS |

| I feel comfortable expressing a dissenting opinion to a colleague with another profession | 5 (4.5-6) | 6 (5-6.75) | NS |

| I feel comfortable expressing a dissenting opinion to a colleague with the same profession | 6 (5-6) | 6 (5-7) | NS |

| I would feel safe here as a patient | 6 (5-7) | 6 (5.25-7) | NS |

| Response options of very low, low, adequate, high, and very high aretranslated into numbers 1 to 5 below, with very low = 1 and very high = 5 | |||

| Describe the quality of your cooperation with the doctors at the endoscopy unit (answer also if you are a doctor) | 4 (4-5) | 4 (3.25-5) | NS |

| Describe the quality of the communication with the doctors at the endoscopy unit (answer also if you are a doctor) | 4 (3-4) | 4 (3-5) | NS |

| Describe the quality of your collaboration with the nurses at the endoscopy unit (answer also if you are a nurse) | 4 (4-5) | 5 (5-5) | P = NS (0.07) |

| Describe the quality of the communication with the nurses at the endoscopy unit (answer also if you are a nurse) | 4 (4-4.5) | 5 (4-5) | NS |

The aim of this study was to develop and implement a person-centered safety checklist at an endoscopy unit and to evaluate the “checklist intervention” in terms of patient safety, person-centeredness, and teamwork. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first checklist in an endoscopy setting that has combined patient safety with a person-centered approach. It was designed as a quality improvement project. During the team training, body language was emphasized, although non-verbal communication was not clearly incorporated into the checklist. The team training was mandatory for those working in the unit during the scheduled training days. Physicians not scheduled to work in the unit on those days were invited to attend either the team training or the open lunch seminar. Despite this invitation, however, only 7 physicians attended the training and 2 attended the lunch seminar. Therefore, one possible explanation for the physicians’ deficient participation during the “summaries” could have been their lack of training. Previous research has shown that team training in non-technical skills is effective for increasing patient safety attitudes and situation awareness[27]. We therefore regard the team training and group discussions as crucial parts of the implementation process.

The most prominent finding was the increase in identity checks performed by the physicians, an effect that remained throughout the first year after the checklist introduction. In endoscopy, as well as any other type of healthcare, patient misidentification can lead to serious harm. Photo documentation and pathology referrals are two of the tasks that physicians are exclusively responsible for at the unit, and by minimizing the risk of patient misidentification by physicians, important safety improvements can be achieved.

Previous studies have shown improvements in collaborative climate and communication when using the WHO SSC[10,11], and a good working climate can have an indirect positive effect on patient safety. In addition, the perceived quality of communication among staff has previously been linked to improved patient outcomes[9]. Although one question on the staff questionnaire indicated improved collaboration in this study, statistical significance could not be shown, most likely due to the small number of participants; hence, this result should be interpreted cautiously.

Although the checklist developed for this study is new, it contains similarities to the WHO SSC. Haynes et al[8] found that the WHO SSC improved patient outcomes, although other researchers have not noted this association[14]. In the current study, besides the increase in identity checks by the physicians, another positive effect on patient safety was the addition of the checklist “summaries,” which most likely contributed to increased team situation awareness and possibly reduced the threshold for speaking up[28]. Other similar projects[16,29] have found that compliance to checklists is suboptimal. This can be seen in the physicians’ lack of participation in half of the observed “summaries” in the current study. We concur with Catchpole and Russ[30], who consider safety checklists to be “complex socio-technical interventions” that should not be seen as quick solutions to safety issues. The implementation of new routines is a time-consuming process, and the implementation of this endoscopy checklist is not an exception. However, if properly used, this new endoscopy checklist could serve as a tool for improved patient safety, with a team training and group discussions serving as a basis for behavioral change.

Can a checklist enhance a person-centered approach? Since there are no clear definitions of person-centered care, we selected aspects of this approach that have been noted as important in the literature[23,24] and included them on the checklist and in the team training sessions. Our ambition was to evaluate if the checklist intervention could enhance person-centered care, but neither the staff questionnaire nor the patient questionnaire shed light on this matter. Although the staff reported an increased importance of patient participation at the unit, which might indicate a greater awareness of this important aspect of person-centered care, the P-value was just slightly over the cut-off value (P = 0.05).

Associations between multi-professional teamwork and patients’ perceptions of quality of care have previously been identified[31]. However, a similar effect could not be shown in this study since the patient baseline questionnaire - with maximal median scores on all items - did not leave room for improvement. Statistical significance was found for one item on the patient questionnaire, namely regarding the repetition of questions by the staff. However, due to the low number of responders to this specific item, it is not clear if this finding is fully representative.

In general patients tend to report high levels of satisfaction[32], which is why other research methods, such as qualitative interviews, might be useful to better understand patients’ views on person-centered care in endoscopy settings.

Some of the strengths in our study design were the inclusion of both patients and staff and the use of observations in addition to questionnaires for data collection. This quality improvement project was implemented and evaluated in a clinical setting with immediate consequences for patients and staff.

In our study, the observations contributed to an understanding of how the checklist was used by the staff. People who are being observed tend to perform differently than normal, so to minimize this bias, a research nurse performed parts of the observations simultaneously with her ordinary tasks.

Suitable existing questionnaires for our study could not be found, and we therefore developed our own based partly on existing validated instruments. Our questionnaires were tested for their usability and relevance. However, the lack of solid validation of the questionnaires is a limitation to our study.

As a quality improvement project, it was important that the implementation leaders were endoscopy staff members as this would increase their buy-in and sense of ownership of the checklist. However, our personal engagement in the research study could have affected the internal validity and generalizability of the findings. In addition, a one-group pretest-posttest design is vulnerable to internal validity threats. In future studies, a standardized model of implementation at multiple sites, together with validated instruments for measuring patient outcomes and potentially qualitative methods, could result in a greater understanding of the complexity of an endoscopy checklist that combines patient safety and person-centeredness and its effects.

In conclusions, the most prominent finding of this study was a statistically significant improvement in patient identity verification by physicians, which is an important patient safety measure. Compliance with the checklist was suboptimal. The staff questionnaires highlight a possible increase in staff’s awareness of patient participation and improved collaboration. The patient questionnaires did not shed light on the study aims; therefore, further investigations at multiple units using a standardized implementation model and more sensitive instruments are needed to further evaluate this concept.

One of the most well-known tools for improving patient safety is the World Health Organization’s Surgical Safety Checklist (WHO SSC), which has been extensively evaluated. Studies have shown that implementing the WHO SSC contributes to better patient outcomes. Improved communication in surgical teams, a factor known to be associated with better patient outcomes, is another positive effect of the WHO SSC.

Within the field of endoscopy, the number of examinations continues to increase; at the same time, this diagnostic process has become more technically advanced. Therefore, knowledge about a patient’s health condition and proper monitoring of the patient’s vital functions are crucial to prevent complications. Safety checklists similar to the WHO SSC that are specific to endoscopy have been described in the literature.

Another approach to improve healthcare quality and patient safety is promoting patient participation. Person-centered care has been described as a collaborative and respectful partnership between healthcare professionals and the patient. This study describes an attempt to combine patient safety with a person-centered approach in the endoscopy field, which to our knowledge has not been done before.

Our motivation was to explore if patient safety aspects could be combined with a person-centered approach in an endoscopy checklist. We also wanted to evaluate the impact of such a checklist. Would this novel checklist contribute to improved team communication and enhanced patient safety as previous checklists have done? Would the addition of a person-centered approach contribute to increased patient participation? Would the staff use the checklist as intended? The study contributes to the current literature through an innovative approach that could be adopted by other high-volume service areas in the medical field.

The main objectives of the study were to describe the development and implementation of a novel person-centered safety checklist and to evaluate the “checklist intervention” in terms of patient safety, person-centeredness, and teamwork.

The intervention in this study was a newly developed endoscopy checklist at a university hospital’s endoscopy unit in Sweden. The checklist was developed by a multi-professional group, and the introduction consisted of half-day sessions including lectures, a team training, and group discussions.

The intervention was evaluated using two methods: structured observations and pre/post questionnaires. The questionnaires were developed by the authors and were tested for their usability and relevance. Questionnaires were collected from both patients and staff. The structured observations included endoscopy teams of physicians and nurses. Anonymized data were analyzed using, when appropriate, the Mann-Whitney U-test, Fischer’s exact test, the χ2, and the Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed-ranks test.

Our observations showed frequent attempts by the physicians and nurses to use the checklist, but with suboptimal compliance.

The most salient result in the study was the increase of patient identity verifications performed by physicians. At baseline, none of the physicians performed identity checks before scope insertion. At 10 mo after the intervention, the identity verifications performed by physicians were observed at 87%.

Neither the staff nor patient questionnaires had statistically significant differences. However, the staff reported an increased awareness of the importance of patient participation, which might indicate a greater emphasis on this important aspect of person-centered care (the P-value was slightly over the cut off value of P = 0.05). These results should be interpreted carefully and need to be investigated further in future studies using validated instruments or other research methods.

This new endoscopy checklist, if properly used, could be a tool for improved patient safety, with a team training and group discussions serving as a basis for behavioral changes. The combination of patient safety aspects and a person-centered approach has been carried out and implemented with immediate positive consequences for patients and staff. However, further research is needed to evaluate the effects of the checklist, especially regarding a teamwork culture and person-centeredness.

Since no suitable questionnaires were found for this context, the authors developed their own. Although this was an educative process, this method was not sufficient to draw conclusions for some of our research objectives. In future work, solid validation is necessary for such questionnaires. Qualitative methods could bring a deeper understanding of patient and staff experiences regarding patient participation and a teamwork culture. To measure patient safety, the checklist should be implemented using standardized methods at multiple sites and by using other patient outcome measures, such as complication rates or near misses.

We are grateful for the participation of patients, nurses, and physicians at the Karolinska University Hospital. A special thanks to research nurses Karin Thourot Nouchi and Lisa Sundin Zarouki, who were of great help in the data collection, and to Donal Barrett, for his expertise in the data analyses.

| 1. | Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press 2000; . |

| 2. | Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare [Socialstyrelsen]. Situation report on patient safety 2015 [Lägesrapport inom patientsäkerhetsområdet 2015]. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen 2015; Available from: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/19753/2015-4-1.pdf. |

| 3. | Amornyotin S. Sedation-related complications in gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:527-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 4. | Blero D, Devière J. Endoscopic complications--avoidance and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:162-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Björkstén KS, Bergqvist M, Andersén-Karlsson E, Benson L, Ulfvarson J. Medication errors as malpractice-a qualitative content analysis of 585 medication errors by nurses in Sweden. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bolton-Maggs PH, Wood EM, Wiersum-Osselton JC. Wrong blood in tube - potential for serious outcomes: can it be prevented? Br J Haematol. 2015;168:3-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | World Health Organization. Patient safety – WHO Surgical Safety Checklist. World Health Organization, 2017. Accessed Mar 28. 2017; Available from: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/checklist/en/. |

| 8. | Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Breizat AH, Dellinger EP, Herbosa T, Joseph S, Kibatala PL, Lapitan MC. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3703] [Cited by in RCA: 3483] [Article Influence: 204.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Davenport DL, Henderson WG, Mosca CL, Khuri SF, Mentzer RM Jr. Risk-adjusted morbidity in teaching hospitals correlates with reported levels of communication and collaboration on surgical teams but not with scale measures of teamwork climate, safety climate, or working conditions. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:778-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Russ S, Rout S, Sevdalis N, Moorthy K, Darzi A, Vincent C. Do safety checklists improve teamwork and communication in the operating room? A systematic review. Ann Surg. 2013;258:856-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Takala RS, Pauniaho SL, Kotkansalo A, Helmiö P, Blomgren K, Helminen M, Kinnunen M, Takala A, Aaltonen R, Katila AJ. A pilot study of the implementation of WHO surgical checklist in Finland: improvements in activities and communication. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55:1206-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Levy SM, Senter CE, Hawkins RB, Zhao JY, Doody K, Kao LS, Lally KP, Tsao K. Implementing a surgical checklist: more than checking a box. Surgery. 2012;152:331-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Russ S, Rout S, Caris J, Mansell J, Davies R, Mayer E, Moorthy K, Darzi A, Vincent C, Sevdalis N. Measuring variation in use of the WHO surgical safety checklist in the operating room: a multicenter prospective cross-sectional study. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:1-11.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Urbach DR, Govindarajan A, Saskin R, Wilton AS, Baxter NN. Introduction of surgical safety checklists in Ontario, Canada. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1029-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 428] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Conley DM, Singer SJ, Edmondson L, Berry WR, Gawande AA. Effective surgical safety checklist implementation. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:873-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Matharoo M, Sevdalis N, Thillai M, Bouri S, Marjot T, Haycock A, Thomas-Gibson S. The endoscopy safety checklist: A longitudinal study of factors affecting compliance in a tertiary referral centre within the United Kingdom. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2015;4:pii: u206344.w2567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | McMillan SS, Kendall E, Sav A, King MA, Whitty JA, Kelly F, Wheeler AJ. Patient-centered approaches to health care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70:567-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:520-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 693] [Cited by in RCA: 723] [Article Influence: 51.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schiffinger M, Latzke M, Steyrer J. Two sides of the safety coin?: How patient engagement and safety climate jointly affect error occurrence in hospital units. Health Care Manage Rev. 2016;41:356-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | World Health Organization. Exploring patient participation in reducing health-care related safety risks. Copenhagen: World Health Organization 2013; Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/185779/e96814.pdf. |

| 21. | Sahlström M, Partanen P, Rathert C, Turunen H. Patient participation in patient safety still missing: Patient safety experts’ views. Int J Nurs Pract. 2016;22:461-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Leplege A, Gzil F, Cammelli M, Lefeve C, Pachoud B, Ville I. Person-centredness: conceptual and historical perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1555-1565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, Lindseth A, Norberg A, Brink E, Carlsson J, Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Johansson IL, Kjellgren K. Person-centered care--ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10:248-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 890] [Cited by in RCA: 1147] [Article Influence: 76.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | De Silva D. Helping measure person-centred care. London: The Health Foundation 2014; . |

| 25. | Matharoo M, Thomas-Gibson S, Haycock A, Sevdalis N. Implementation of an endoscopy safety checklist. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2014;5:260-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB, Rowan K, Vella K, Boyden J, Roberts PR, Thomas EJ. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 923] [Cited by in RCA: 1065] [Article Influence: 53.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Matharoo M, Haycock A, Sevdalis N, Thomas-Gibson S. Endoscopic non-technical skills team training: the next step in quality assurance of endoscopy training. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17507-17515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Gaba DM, Howard SK, Small SD. Situation awareness in anesthesiology. Hum Factors. 1995;37:20-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Erestam S, Haglind E, Bock D, Andersson AE, Angenete E. Changes in safety climate and teamwork in the operating room after implementation of a revised WHO checklist: a prospective interventional study. Patient Saf Surg. 2017;11:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Catchpole K, Russ S. The problem with checklists. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:545-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Muntlin Athlin Å, Farrokhnia N, von Thiele Schwarz U. Teamwork - a way to improve patient perceptions of the quality of care in an emergency department: An intervention study with follow-up. Eur J Pers Cent Healthc. 2016;4:509-519. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Williams B, Coyle J, Healy D. The meaning of patient satisfaction: an explanation of high reported levels. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1351-1359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Sweden

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Contini S, Richter JM S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma YJ