Published online Dec 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i48.8597

Peer-review started: August 15, 2017

First decision: August 29, 2017

Revised: October 31, 2017

Accepted: November 14, 2017

Article in press: November 14, 2017

Published online: December 28, 2017

Processing time: 135 Days and 0.1 Hours

To describe the efficacy and safety of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation (EPLBD) in the management of bile duct stones in a Western population.

Data was collected from the endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and Radiology electronic database along with a review of case notes over a period of six years from 1st August 2009 to 31st July 2015 and incorporated into Microsoft excel. Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc for Windows, version 12.5 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). Simple statistical applications were applied in order to determine whether significant differences exist in comparison groups. We initially used simple proportions to describe the study populations. Furthermore, we used chi-square test to compare proportions and categorical variables. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test was applied in order to compare continuous variables. All comparisons were deemed to be statistically significant if P values were less than 0.05.

EPLBD was performed in 229 patients (46 females) with mean age of 68 ± 14.3 years. 115/229 (50%) patients had failed duct clearance at previous ERCP referred from elsewhere with standard techniques. Duct clearance at the Index* ERCP (1st ERCP at our centre) was 72.5%. Final duct clearance rate was 98%. EPLBD after fresh sphincterotomy was performed in 81 (35.4%). Median balloon size was 13.5 mm (10 - 18). In addition to EPLBD, per-oral cholangioscopy (POC) and electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) was performed in 35 (15%) patients at index* ERCP. 63 (27.5%) required repeat ERCP for stone clearance. 28 (44.5%) required POC and EHL and 11 (17.4%) had repeat EPLBD for complete duct clearance. Larger stone size (12.4 mm vs 17.4 mm, P < 0.000001), multiple stones (2, range (1-13) vs 3, range (1-12), P < 0.006) and dilated common bile duct (CBD) (12.4 mm vs 18.3 mm, P < 0.001) were significant predictors of failed duct clearance at index ERCP. 47 patients (20%) had ampullary or peri-ampullary diverticula. Procedure related adverse events included 2 cases of bleeding and pancreatitis (0.87%) each.

EPLBD is a safe and effective technique for CBDS removal. There is no difference in outcomes whether it is performed at the time of sphincterotomy or at a later procedure or whether there is a full or limited sphincterotomy.

Core tip: This is one of the largest published series describing the management of difficult biliary stone disease utilizing large balloon sphincteroplasty in a Western population. Our findings suggest that large balloon sphincteroplasty can be performed and repeated safely and effectively in those with a sphincterotomy irrespective of its timing and size to establish complete duct clearance.

- Citation: Aujla UI, Ladep N, Dwyer L, Hood S, Stern N, Sturgess R. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation with sphincterotomy is safe and effective for biliary stone removal independent of timing and size of sphincterotomy. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(48): 8597-8604

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i48/8597.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i48.8597

Common bile duct stones (CBDS) are diagnosed frequently throughout the world. The prevalence of CBDS in symptomatic gallstone disease is estimated between 10% and 20%[1-3]. Extraction of confirmed CBDS in symptomatic patients is recommended[4]. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is recognized as an effective treatment modality for CBDS extraction. Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) followed by stone extraction with balloon or basket has been used traditionally as a standard technique. Large or multiple stones however, may be technically challenging with standard techniques and may require additional treatment modalities including mechanical lithotripsy for successful stone extraction[5-7].

Endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation (EPBD) for biliary stones extraction was first reported in 1982[8]. EPBD without an EST has been reported but is associated with an increased risk of pancreatitis and reduced stone clearance rates[9]. In a Cochrane review, EPBD compared to EST has been associated with less risk of bleeding but increased risk of post ERCP pancreatitis[10].

EST followed by endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation (EST+EPLBD) using a balloon sized 10-20mm was reported in 2003 as an effective and safe treatment of CBDS[11]. EPLBD with limited or full EST has subsequently emerged as an established endoscopic technique in the management of CBDS mainly in Asia based on published data[12]. Interestingly, more recent data has suggested that endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation (EPLBD) alone without a preceding EST is a useful technique in CBDS removal with comparable outcomes to EST[13,14].

The safety profile and effectiveness of EPLBD with limited or full EST has been reported in most studies[15-27]. However, concerns remain regarding serious adverse events[28-32] including procedure related morbidity and mortality limiting wider application of EPLBD in the management of CBDS.

There remains a significant variation in practice when performing large balloon papillary dilatation with particular concerns to the timing and size of sphincterotomy prior to balloon dilatation. This study describes the safety profile and effectiveness of EPLBD in the management of CBDS and examines the impact of timing and size of sphincteroplasty in relation to EST in a Western population.

This study from a United Kingdom academic referral centre involved 229 patients who had EPLBD for retrieval of CBDS from 1st August 2009 to 31st July 2015. Of these, 115 (50%) patients had previous unsuccessful stone extraction elsewhere. Inclusion criteria were: adult patients with confirmed CBDS and who gave consent for the procedure. Excluded from the study were patients with coagulopathy (INR > 1.5), thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 50000/mL), and those who had distal biliary stricture.

ERCP was undertaken predominantly with benzodiazepine and opioid sedation. General anesthesia was used when per-oral cholangioscopy (POC) (SpyGlassTMDS, Boston Scientific, MA, United States) was performed.

ERCP was performed using side-viewing endoscopes (TJF-240; Olympus Optical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Standard wire guided EST was performed for native papilla. Stone extraction was attempted with extractor balloon catheter (ExtractorTM Pro RX, 2 lumen extraction balloon, Boston Scientific, Cork, Ireland and/or Multi-3V PlusTM, three lumen extraction balloon, Olympus Medical systems, Tokyo, Japan) and/or wire guided retrieval basket (TrapezoidTM, Boston Scientific Limited, Ireland).

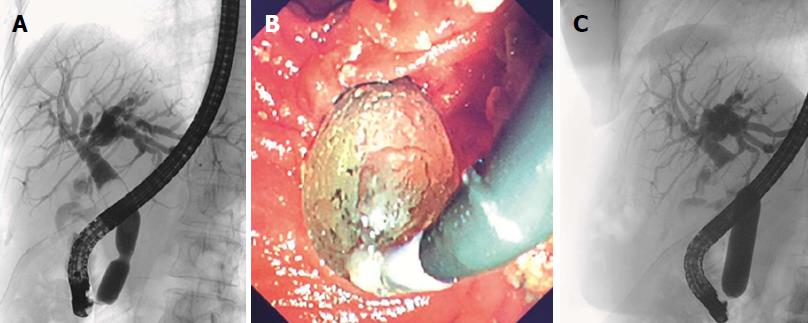

Where stone retrieval was unsuccessful with standard techniques, EPLBD (CRETM Wire guided, Boston Scientific, Cork, Ireland) was performed for stone extraction. The balloon was inflated until disappearance of the waist (Figure 1). For complex and large stones, POC supplemented with electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) (Nortech Autolith, Intracorporeal Electrohydraulic Lithotripter, Northgate Technologies INC, IL, United States) was used for stone extraction. Duct clearance was confirmed with an occlusion cholangiogram. Stone number, size and bile duct diameter were assessed with calibrated hospital radiology software tools on captured fluoroscopic images for accurate precision.

The primary endpoint was common bile duct clearance. Secondary endpoints were procedure related adverse events (pancreatitis, bleeding, cholangitis, perforation and mortality).

This was a cross-sectional study in which consecutive patients who underwent EPLBD during the defined period were evaluated based on study endpoints. Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc for Windows, version 12.5 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). Simple statistical applications were applied in order to determine whether significant differences exist in comparison groups. We initially used simple proportions to describe the study populations. Furthermore, we used chi-square test to compare proportions and categorical variables. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test was applied in order to compare continuous variables. All comparisons were deemed to be statistically significant if P values were less than 0.05.

Two hundred and twenty-nine subjects (146, females) fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Of these, 166 (72.5%) achieved duct clearance at index ERCP. In order to determine factors associated with duct clearance at index ERCP, subjects were divided into 2 groups according to duct clearance (A) and those who failed clearance (B). Only female gender was associated with failed duct clearance at index ERCP (P = 0.046).

| Variables | Group A (n = 166) | Group B (n = 63) | P value |

| Mean age | 68.4 ± 14.3 | 68.4 ± 14.1 | 0.93 |

| Sex (M: F) | 70:96 | 17:46 | 0.046 |

| HTN | 65 (39.2) | 26 (41.3) | 0.88 |

| IHD | 19 (11.4) | 7 (11.1) | 0.87 |

| DM | 14 (8.4) | 4 (6.3) | 0.80 |

| CLD | 1 (0.6) | None | 0.60 |

| COPD | 16 (9.6) | 5 (7.9) | 0.89 |

| CKD | 7 (4.2) | 2 (3.2) | 0.98 |

Large stone size, multiple stones and dilated common bile duct were significant predictors of failed duct clearance at index ERCP (Table 2). Overall median balloon diameter used was 13.5 (10-18) mm (Table 3).

| Variables | Group A (n = 166) | Group B (n = 63) | P value |

| Number of stones | 2 (1-13) | 3 (1-12) | 0.006 |

| Median diameter of stones (mm) | 12.4 (4.5-30) | 17.4 (10.1-32) | < 0.000001 |

| Median diameter of duct (mm) | 12.4 (5-30) | 18.3 (9.2-30) | 0.001 |

| Ampullary or peri-ampullary diverticulum | 37 (22.3) | 10 (15.9) | 0.370 |

| Intact GB | 117 (70.5) | 50 (79.4) | 0.240 |

| Primary stone disease | 118 (71.1) | 44 (69.8) | 0.980 |

| Recurrent stone disease1 | 48 (28.9) | 19 (30.2) | 0.900 |

| Balloon size | n | Percent |

| 10-11 mm | 62 | 27% |

| 12-15 mm | 139 | 61% |

| 16-18 mm | 28 | 12% |

EST was performed at index ERCP in 81 (35.4%) and had previously been performed in 148 (64.6%) patients. Procedure time was significantly prolonged in those who failed to achieve duct clearance at index ERCP (30.5 min vs 44 min, P < 0.001) (Table 4).

| Variables | Group A (n = 166) | Group B (n = 63) | P value |

| Procedure time (min) | 30.5 (9-160) | 44 (12-90) | 0.0010 |

| Number of ERCP (median) | 1 (1-3) | 2 (1-10) | 0.0001 |

| Pre-cut sphincterotomy | 6 (3.6) | 2 (3.2) | 0.8000 |

| Previous Sphincterotomy | 106 (63.9) | 42 (66.7) | 0.8000 |

| Fresh Sphincterotomy | 58 (35.5) | 23 (36.5) | 0.9800 |

| Median Balloon size diameter | 13 (10-18) | 13.5 (10-18) | 0.2200 |

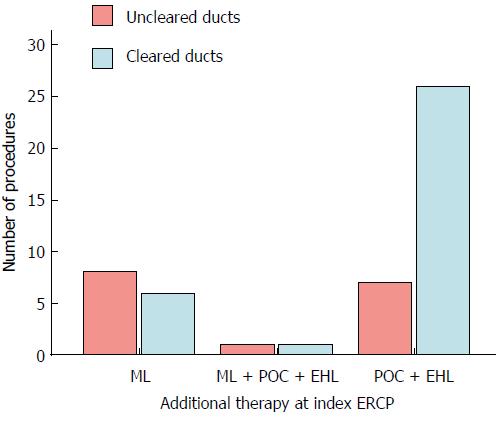

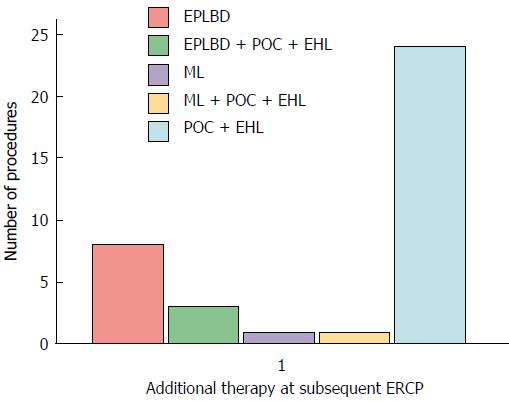

POC supplemented with EHL was the most commonly used additional treatment modality for stone extraction at index and subsequent ERCPs (Figures 2 and 3).

Initial duct clearance rate with EPLBD at index ERCP was 72.5%. However, all cases of failed duct clearance (Group B) at index ERCP underwent further ERCP for duct clearance. Final duct clearance rate was 97.8%.

The procedure related adverse events are listed in Table 5. Post ERCP pancreatitis and haemorrhage were not significantly different between groups. There was no case of procedure related mortality.

| Variables | Group A (n = 166) | Group B (n = 63) | P value |

| Pancreatitis | 0 | 2 (3.2) | 0.13 |

| Bleeding | 2 (1.2) | 0 | 0.93 |

| Cholangitis | None | None | NA |

| Perforation | None | None | NA |

| Mortality | None | None | NA |

We report an experience of EPLBD based on intention to treat analysis from an academic United Kingdom endoscopy centre. The study shows that EST followed by immediate or delayed EPLBD (EST + EPLBD) is a safe and an effective approach. Duct clearance was achieved in 73% of the patients at index ERCP and further procedures produced an overall duct clearance rate of 98%. Procedure related complications were reported in only four patients (1.7%). EPLBD was performed immediately after sphincterotomy in 35% of the patients. The study results reveal comparable and even lower rates of complications including pancreatitis, perforation and bleeding than previously reported[10,28-30,32].

This is probably the largest single centre study in a Western population reporting the use of endoscopic large volume balloon dilatation in managing CBDS, in which 229 patients were included. A recent literature review reported data from 32 studies across the globe[12]. The largest study of this review, which was from China, included 169 patients.

In contrast to other published series reporting higher initial duct clearance rates, we observed relatively lower duct clearance rates at index ERCP. The reason for this is related to the more complex nature of stone disease in a referral population. Complexity of the stone disease in our cohort may be evident with the fact that all patients required large balloon sphincteroplasty in addition to the standard endoscopic techniques for stone extraction at the index ERCP. In addition to EPLBD using POC together with EHL could not achieve duct clearance in (3.5%) of patients at the index ERCP (Figure 2). Furthermore, 45% of the patients undergoing repeat ERCP for duct clearance required POC and EHL (Figure 3).

50% of the patients with first EPLBD performed at our centre had previously failed stone extraction with standard endoscopic techniques including EST followed by stone extraction with balloon and basket performed by the referring unit. Among those 50% with previous unsuccessful stone extraction, complete duct clearance was achieved with EPLBD in approximately 70% of the cases at index ERCP. Patients with failed duct clearance at index ERCP had significantly large stone size 17.4 (10.1-32) mm vs 12.4 (4.5-30) mm, P < 0.000001, multiple stones [2, range (1-13) vs 3, range (1-12), P < 0.006] and dilated bile duct 18.3 mm (9.2-30) mm vs 12.4 mm (5-30), P < 0.001.

In a systemic review and meta-analysis[33] initial duct clearance rates for stones larger than 15mm was 77% in the EPLBD group. Initial duct clearance rates with EST + EPLBD vary from 72.7% to 100% in published series[12] which are mainly from Asia. In a recent study from Australia[34] initial duct clearance rates were 70% in immediate EPLBD group and 74% in delayed EPLBD group.

Major adverse events (AEs) related to EST and EPLBD are pancreatitis, bleeding, and perforation. A recent Australian retrospective study[34] reviewed outcomes of EPLBD and EST in 136 patients. Only one case of non-fatal pancreatitis and a perforation was observed in the delayed EPLBD group. Three cases of non-fatal haemorrhage were observed in immediate and delayed EPLBD group (P = 0.303). The safety profile of EPLBD has been corroborated by a recent meta-analysis[33] in which four randomized controlled trials (RCT) comparing EST plus EPLBD vs EST alone and EST plus mechanical lithotripsy were assessed. In the three RCTs comparing EPLBD with EST alone there were no statistical differences in terms of each form of adverse events: PEP (3% vs 3.4%); haemorrhage (0.5% vs 1%); cholangitis (1.5% vs 1.9); perforation (0% vs 1%). In the RCT comparing EPLBD with EST plus ML higher rates of cholangitis were observed 0% vs 13.3 (P = 0.026). In one of these RCTs[23] less overall adverse events were observed with EST + EPLBD than after EST alone (4.4% vs 20%, P = 0.049). This emphasises the safety profile of EPLBD.

A review of 32 studies involving 1761 patients, demonstrated overall rates of AEs related to EST combined with EPLBD including perforation, pancreatitis, bleeding and cholangitis were 0.4%, 2.7%, 2.2% and 0.9% respectively[12]. A retrospective multicenter study[28] investigating 946 patients reported 9 perforations (0.95%), resulting in 3 deaths. Distal CBD stricture (OR = 17.08, P < 0.001) was an independent predictor for perforation. In a systemic review of 30 studies[35] the overall AEs were significantly lower in EST combined with EPLBD group than in EST alone (8.3% vs 12.7%, OR = 1.60, P < 0.001).

Our AEs rates were not only comparable but even much lower than most of the published data. Pancreatitis was defined according to the consensus criteria described elsewhere. The overall pancreatitis rate in our cohort was 2/229 (0.87%). Both cases had non-fatal pancreatitis and were managed conservatively. In both these cases duct clearance was not achieved at index ERCP with EPLBD. This is one of the principal emphases of the study that in our experience EPLBD was not associated with significantly increased risk of post ERCP pancreatitis. Peri-procedural optimization of patients is our standard practice to prevent post ERCP pancreatitis. This includes providing adequate intravenous hydration, prescribing rectal diclofenac and keeping a low threshold for placement of pancreatic stents for contrast injection and wire cannulation of pancreatic duct. These preventive measures along with rich high volume experience are probably the principal factors for a very low rate of post ERCP pancreatitis. Similarly, 2 cases (0.87%) of gastrointestinal haemorrhage were observed. One patient required blood transfusion and endoscopic haemostatic therapy. The other patient required two units of blood transfusion. There was no procedure related perforation, cholangitis or mortality.

Twenty percent of the patients in our study had periampullary diverticula (PAD), which did not impact on the incidence of the adverse events or duct clearance. In patients with and without PAD, overall duct clearance and adverse events rates were similar in retrospective studies[24,36] comparing EPLBD with limited EST or EPLBD alone.

In our study, the balloon was inflated until the disappearance of the waist rather than specific time duration. Hence, the balloon inflation time would have been relatively short. A meta-analysis[37] has reported an inverse relation of pancreatitis with balloon timing but this clearly was not the case in our scenario.

POC and EHL were planned in addition to EPLBD in 35 (15.3%) of the patients at index ERCP in view of previously demonstrated complex stone disease on cholangiographic appearances. In 8 (3.5%) patients, EPLBD even supplemented with POC and EHL could not clear the bile ducts due to complex nature of stone disease at index ERCP.

Prior to the introduction of EPLBD, ML was generally used after EST. In these circumstances, ML is traditionally used after EST. However, it may be time consuming and technically challenging with an increase risk of procedure related adverse events[23]. In our practice, EPLBD was the preferred treatment modality over ML and limited its use to 7% of the procedures. Recently published international consensus guidelines for EPLBD reaffirm our findings and recommend its use as preferred and alternative modality to ML in removing large bile duct stones[38].

Our experience of EST with immediate or delayed large balloon dilatation confirms its safety and effectiveness. We conclude that the safety of large balloon sphincteroplasty is not influenced by the presence of a periampullary diverticulum or a fresh sphincterotomy. Limited or full sphincterotomy followed by EPLBD does not influence the outcomes. Our results suggest that a significant proportion of patients with multiple stones and large stones may require additional treatment modalities including cholangioscopy and EHL where large balloon sphincteroplasty remains unsuccessful in achieving duct clearance.

Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation (EPLBD) is an established technique for biliary stone extraction mainly in Asia. Serious adverse events related to EPLBD including pancreatitis, bleeding and perforation have limited its wider utility particularly in the Western world. Timing and size of preceding endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) impose significant concerns regarding serious procedure related adverse events. This study describes the safety and efficacy of EPLBD in the management of CBDS and examines the impact of timing and size of sphincteroplasty in relation to EST in a Western population.

EPLBD is being performed very frequently in day to day practice. There is insufficient data on its efficacy and safety without any standardized techniques. There is little data on timing and hence an appreciation that there is variation in practice in some centres performing a sphincteroplasty on a subsequent and further endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. The principal motive of the study was to ascertain whether EPLBD could be performed safely as an effective and preferred endoscopic modality for complex biliary stone extraction following EST.

The main objectives of the study were to describe the efficacy and safety of EPLBD in the management of bile duct stones in a Western population from the experience in a busy tertiary referral unit.

This was a retrospective observational study in which consecutive patients who underwent EPLBD during the defined period were evaluated based on study endpoints.

This study confers high safety profile of EPLBD for biliary stone extraction in relation to an EST. The study also ascertains EPLBD as an effective and preferred endoscopic modality than standard endoscopic techniques for complex bile duct stones management. The problems that remain to be solved are the predictive factors indicating the need for EPLBD and factors predicting failure.

EPLBD is a safe and effective technique for biliary stone extraction. Safety of large balloon sphincteroplasty is not influenced by the presence of a periampullary diverticulum or a fresh sphincterotomy. Limited or full sphincterotomy followed by EPLBD does not influence the outcomes. Large and multiple stones may predict need for additional treatment modalities including cholangioscopy and electrohydraulic lithotripsy where large balloon sphincteroplasty remains unsuccessful in achieving duct clearance.

This study suggests that large balloon sphincteroplasty can be performed and repeated safely and effectively in those with a sphincterotomy irrespective of its timing and size to establish complete duct clearance.

| 1. | Neuhaus H, Feussner H, Ungeheuer A, Hoffmann W, Siewert JR, Classen M. Prospective evaluation of the use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography prior to laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Endoscopy. 1992;24:745-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lacaine F, Corlette MB, Bismuth H. Preoperative evaluation of the risk of common bile duct stones. Arch Surg. 1980;115:1114-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Houdart R, Perniceni T, Darne B, Salmeron M, Simon JF. Predicting common bile duct lithiasis: determination and prospective validation of a model predicting low risk. Am J Surg. 1995;170:38-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Warttig S, Ward S, Rogers G; Guideline Development Group. Diagnosis and management of gallstone disease: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2014;349:g6241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Higuchi T, Kon Y. Endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy for the treatment of common bile duct stone. Experience with the improved double sheath basket catheter. Endoscopy. 1987;19:216-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Moriai T, Hasegawa T, Fuzita M, Kimura A, Tani T, Makino I. Successful removal of massive intragastric gallstones by endoscopic electrohydraulic lithotripsy and mechanical lithotripsy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:627-629. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Hintze RE, Adler A, Veltzke W. Outcome of mechanical lithotripsy of bile duct stones in an unselected series of 704 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:473-476. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Staritz M, Ewe K, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Endoscopic papillary dilatation, a possible alternative to endoscopic papillotomy. Lancet. 1982;1:1306-1307. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Zhao HC, He L, Zhou DC, Geng XP, Pan FM. Meta-analysis comparison of endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation and endoscopic sphincteropapillotomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3883-3891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Weinberg BM, Shindy W, Lo S. Endoscopic balloon sphincter dilation (sphincteroplasty) versus sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4) CD004890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Ersoz G, Tekesin O, Ozutemiz AO, Gunsar F. Biliary sphincterotomy plus dilation with a large balloon for bile duct stones that are difficult to extract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:156-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rouquette O, Bommelaer G, Abergel A, Poincloux L. Large balloon dilation post endoscopic sphincterotomy in removal of difficult common bile duct stones: a literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7760-7766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jeong S, Ki SH, Lee DH, Lee JI, Lee JW, Kwon KS, Kim HG, Shin YW, Kim YS. Endoscopic large-balloon sphincteroplasty without preceding sphincterotomy for the removal of large bile duct stones: a preliminary study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:915-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Oh MJ, Kim TN. Prospective comparative study of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation and endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of large bile duct stones in patients above 45 years of age. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1071-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Minami A, Hirose S, Nomoto T, Hayakawa S. Small sphincterotomy combined with papillary dilation with large balloon permits retrieval of large stones without mechanical lithotripsy. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2179-2182. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Maydeo A, Bhandari S. Balloon sphincteroplasty for removing difficult bile duct stones. Endoscopy. 2007;39:958-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Heo JH, Kang DH, Jung HJ, Kwon DS, An JK, Kim BS, Suh KD, Lee SY, Lee JH, Kim GH. Endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large-balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bile-duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:720-726; quiz 768, 771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Attasaranya S, Cheon YK, Vittal H, Howell DA, Wakelin DE, Cunningham JT, Ajmere N, Ste Marie RW Jr, Bhattacharya K, Gupta K, Freeman ML, Sherman S, McHenry L, Watkins JL, Fogel EL, Schmidt S, Lehman GA. Large-diameter biliary orifice balloon dilation to aid in endoscopic bile duct stone removal: a multicenter series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:1046-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Itoi T, Itokawa F, Sofuni A, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Moriyasu F. Endoscopic sphincterotomy combined with large balloon dilation can reduce the procedure time and fluoroscopy time for removal of large bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:560-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Kim KO, Kim TN, Lee SH. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation for the treatment of recurrent bile duct stones in patients with prior sphincterotomy. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1283-1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kurita A, Maguchi H, Takahashi K, Katanuma A, Osanai M. Large balloon dilation for the treatment of recurrent bile duct stones in patients with previous endoscopic sphincterotomy: preliminary results. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1242-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim TH, Oh HJ, Lee JY, Sohn YW. Can a small endoscopic sphincterotomy plus a large-balloon dilation reduce the use of mechanical lithotripsy in patients with large bile duct stones? Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3330-3337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Stefanidis G, Viazis N, Pleskow D, Manolakopoulos S, Theocharis L, Christodoulou C, Kotsikoros N, Giannousis J, Sgouros S, Rodias M. Large balloon dilation vs. mechanical lithotripsy for the management of large bile duct stones: a prospective randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:278-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim HW, Kang DH, Choi CW, Park JH, Lee JH, Kim MD, Kim ID, Yoon KT, Cho M, Jeon UB. Limited endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large balloon dilation for choledocholithiasis with periampullary diverticula. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4335-4340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Itoi T, Ishii K, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Sofuni A. Large balloon papillary dilation for removal of bile duct stones in patients who have undergone a billroth ii gastrectomy. Dig Endosc. 2010;22 Suppl 1:S98-S102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sakai Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Sugiyama H, Nishikawa T, Kurosawa J, Saito M, Tawada K, Mikata R, Tada M, Ishihara T. Endoscopic sphincterotomy combined with large balloon dilation for removal of large bile duct stones. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:58-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Teoh AY, Cheung FK, Hu B, Pan YM, Lai LH, Chiu PW, Wong SK, Chan FK, Lau JY. Randomized trial of endoscopic sphincterotomy with balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy alone for removal of bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:341-345.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Park SJ, Kim JH, Hwang JC, Kim HG, Lee DH, Jeong S, Cha SW, Cho YD, Kim HJ, Kim JH. Factors predictive of adverse events following endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation: results from a multicenter series. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1100-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Disario JA, Freeman ML, Bjorkman DJ, Macmathuna P, Petersen BT, Jaffe PE, Morales TG, Hixson LJ, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Endoscopic balloon dilation compared with sphincterotomy for extraction of bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1291-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Fujita N, Maguchi H, Komatsu Y, Yasuda I, Hasebe O, Igarashi Y, Murakami A, Mukai H, Fujii T, Yamao K. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation for bile duct stones: A prospective randomized controlled multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:151-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Arnold JC, Benz C, Martin WR, Adamek HE, Riemann JF. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation vs. sphincterotomy for removal of common bile duct stones: a prospective randomized pilot study. Endoscopy. 2001;33:563-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lee TH, Park SH, Lee CK, Chung IK, Kim SJ, Kang CH. Life-threatening hemorrhage following large-balloon endoscopic papillary dilation successfully treated with angiographic embolization. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E241-E242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Xu L, Kyaw MH, Tse YK, Lau JY. Endoscopic sphincterotomy with large balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:673103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Ho S, Rayzan D, Fox A, Kalogeropoulos G, Mackay S, Hassen S, Banting S, Cade R. Endoscopic sphincterotomy with sphincteroplasty for the management of choledocholithiasis: a single-centre experience. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:695-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kim JH, Yang MJ, Hwang JC, Yoo BM. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation for the removal of bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8580-8594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lee JW, Kim JH, Kim YS, Choi HS, Kim JS, Jeong SH, Ha MS, Ku YS, Kim YS, Kim JH. [The effect of periampullary diverticulum on the outcome of bile duct stone treatment with endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;58:201-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Liao WC, Tu YK, Wu MS, Wang HP, Lin JT, Leung JW, Chien KL. Balloon dilation with adequate duration is safer than sphincterotomy for extracting bile duct stones: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1101-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kim TH, Kim JH, Seo DW, Lee DK, Reddy ND, Rerknimitr R, Ratanachu-Ek T, Khor CJ, Itoi T, Yasuda I. International consensus guidelines for endoscopic papillary large-balloon dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:37-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Bramhall S, Chow WK, Tsuyuguchi T S- Editor: Chen K L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y