Published online Jul 14, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4253

Revised: May 23, 2008

Accepted: May 30, 2008

Published online: July 14, 2008

We present the case of a 57-year-old man who underwent esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma found at barium meal and gastroscopic examination. He was diagnosed as esophageal basaloid squamous carcinoma (BSC) and gastric stromal tumor, which were associated with focal proliferation of melanocytes/pigmentophages and hair follicles in esophageal mucosa. Melanocytic hyperplasia (melanocytosis) has previously been recognized as an occasional reactive lesion, which can accompany esophageal inflammation and invasive squamous carcinoma. The present case is unusual because of its hyperplasia of not only melanocytes but also hair follicles. To our knowledge, this is the first report of esophageal blue nevus and hair follicle coexisting with BSC.

- Citation: Wang DG, Li XG, Gao H, Sun XY, Zhou XQ. Coexistence of esophageal blue nevus, hair follicles and basaloid squamous carcinoma: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(26): 4253-4256

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i26/4253.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.4253

Scattered melanocytes at the epithelio-stromal junction of esophageal mucosa are an incidental finding. This phenomenon was first described in 1963 by De la Pava, who found melanocytes in 4% of his autopsy material from the esophagus[1]. Subsequent studies showed that the incidence of esophageal melanocytes ranges 2.5%-8%[23].

The increased number of esophageal melanocytes along the epithelio-stromal junction is considered benign and has been described in association with chronic esophagitis, squamous epithelial hyperplasia and infiltrating squamous carcinoma of the esophageal mucosa[2].

In the present report, we describe a very unusual proliferation form of melanocytes and hair follicles in esophageal mucosa, which is associated with basaloid squamous carcinoma (BSC) of esophagus and gastric stromal tumor. To our knowledge, esophageal blue nevus coexisting with hair follicles is first described.

A 57-year-old man complained of feeling an aggravating obstruction when taking food for 3-mo, which was more severe and affected his normal diet when taking solid food. He had no vomiting, abdominal pain or melena. Physical examination revealed no obvious anemia. The lung and heart sounds were normal, the abdomen was soft and flat with no hepatomegaly or splenomegaly or palpable abdominal mass. Rectal examination found no abnormalities and no enlargement of the superficial lymph nodes. He had an over 30-year history of gastroesophageal reflux disease, and an over 10-year history of chronic gastritis with occasional duodenal ulcer. To cure these diseases, he took soda tablets/powder and other drugs in the past 6-7 years. The patient smoked more than twenty cigarettes and drank 100-150 mL alcohol per day. His family medical history and physical examination were negative. At the lower third esophagus, barium meal examination indicated an esophageal carcinoma, gastroscopic examination showed a 1 cm × 1 cm smooth protrusion and a 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm mucosa erosion on its top, identified by subse-quent biopsy as a low-differentiation carcinoma. The patient underwent a lower third esophagectomy with gastric tube reconstructed.

The surgical specimen including the dissected lymph nodes was fixed in a 4% buffered formalin solution. All the samples taken from the esophagus and stomach were embedded in paraffin for routine histology. All sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE).

Immunohistochemistry was performed on selected paraffin sections using a standard avidin-biotin complex method with diaminobenzidine as chromogen. Monoclonal antibodies against CD117, CD34, SMA, S100 protein (S-100), were used.

The surgical specimen consisted of the lower-third esophageal tissue and the proximal tissue of the stomach including two tumid lymph nodes around the esophagus and one lymph node from the lesser gastric curvature. Another specimen was resected from the subserosa of gastric anterior wall.

Gross examination revealed that the esophageal mucosa was regular and smooth. A 2.5 cm × 1.5 cm tumor was found 1 cm away from the lower margin and 4 cm near the upper margin. The tumor was found to be gray-white with weak mucus shine, and easy to be separated from muscularis. No visible pigmentation was found in esophageal mucosa. The specimen from the gastric part including the squamo-columnar junction appeared normal.

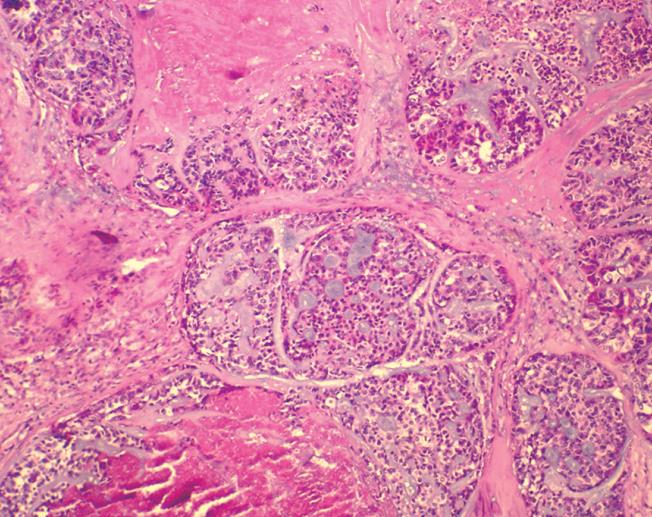

Microscopy revealed that the tumor occupied the area from lamina propria to submucosa and crossed the muscularis mucosa in the lower third of esophagus. Histologiclly, the basaloid cells were arranged mainly in the form of solid, smooth-contoured lobules, or in the form of solid sheets, anastomosing trabeculae, or microcystic structures. Eosinophilic hyaline materials were found in the intertrabecular spaces and stroma of the tumor. The microcystic spaces contained basophilic mucoid matrix. The basaloid cells were round or oval in shape with scant amphophilic cytoplasm, but sometimes they were abundant and clear. The nuclei showed either dark hyperchromatin or vacuolated nucleoplasm with 1 to 3 small distinct nucleoli. The number of mitoses was 15 under 10 high-power fields. The cells at the edges of basaloid islands tended to show peripheral nuclear palisading. Comedo necrosis was found within the basaloid lobules (Figure 1), mimicking adenoid cystic carcinoma and basaloid carcinoma without association with dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, squamous cell carcinoma, or focal squamous cell differentiation. It did not invade the muscularis. No malignant cells were observed in the two resection margins. All lymph nodes were free of malignant cells.

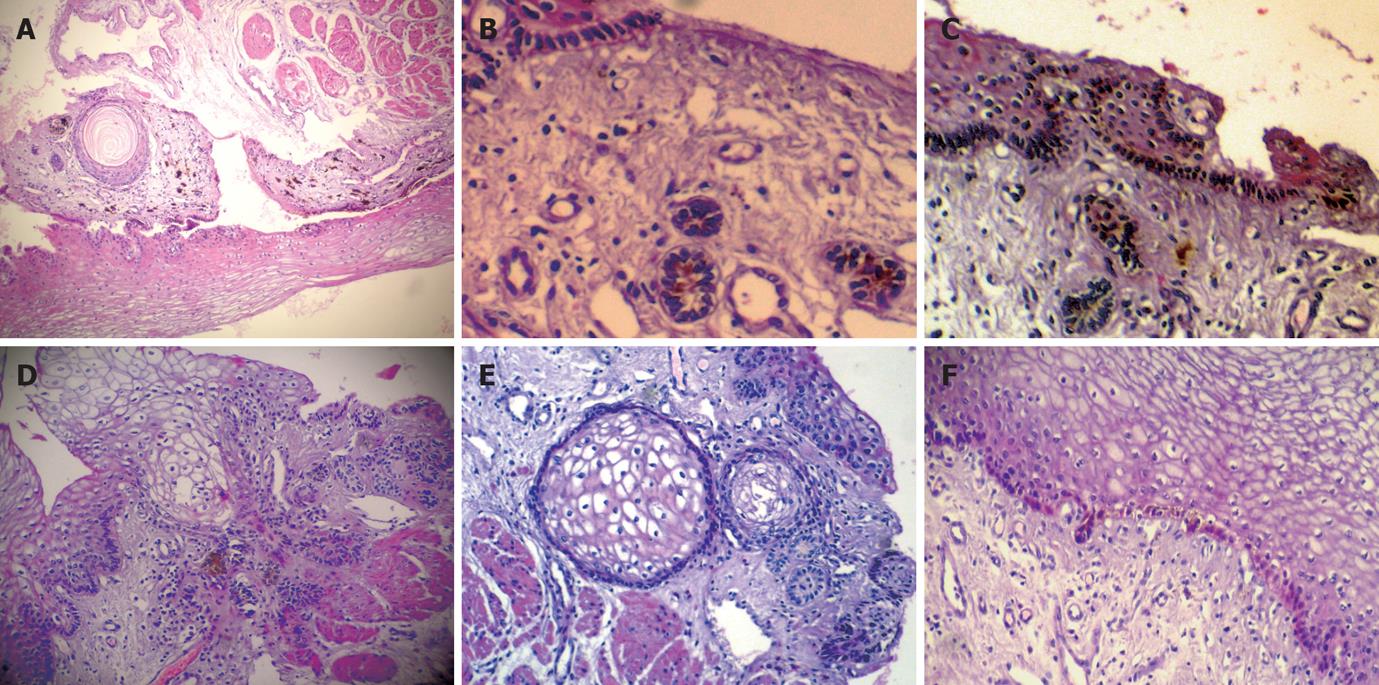

The mucosa of the upper resection margin exhibited a population of melanocytes/pigmentophages. The melanocytes were focally distributed in keratinocytes of the basal esophageal mucosa layer. Heavily pigmented, spindled or dendritic melanocytes/pigmentophages were located predominately in the superficial lamina propria, which were parallel to the covering epithelium and vertical to the long esophagus axis. The spindle and dendritic cells displayed no cytologic atypia and mitoses, in which the small nuclei were covered by the pigment. The pigmented cells occupied about 1 mm, and the thickness was no more than 1 mm. We did not find pigmented cells any more when we recut the specimen embedded in paraffin (Figure 2A). Moreover, there was single or cluster of hair follicles and horn cysts in the mucosa with melanocytes (Figure 2A-E). Similarly, below the esophageal carcinoma, melanocytes were focally distributed in keratinocytes of the basal esophageal mucosa layer, but not in hair follicles or horn cysts (Figure 2F).

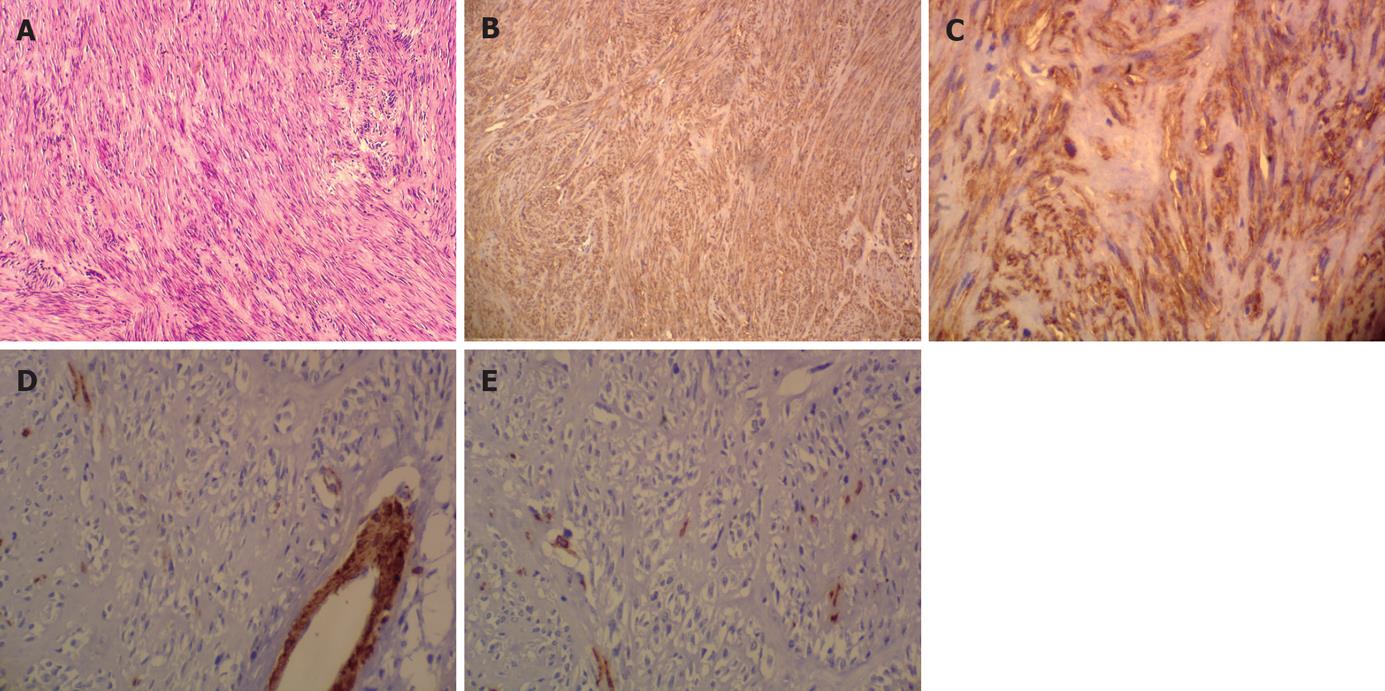

The gastric tumor consisted of basophilic spindle-cells, which were arranged in short fascicles but could be aligned in a strikingly Schwannian pattern with prominent nuclear palisading but no mitotic activity and necrosis (Figure 3A). Immunohistochemistry showed that these cells exhibited a strong immunoreactivity on CD117 (Figure 3B) and CD34 (Figure 3C). No specific reaction to the antibodies SMA (Figure 3D) and S-100 (Figure 3E) was observed.

Based on morphology and marker pattern, a diagnosis of esophageal BSC and low malignant potential gastric stromal tumor was made with blue nevus and hair follicle proliferation.

During early embryogenesis, melanocytes migrate from the neural crest to the epidermis, hair follicles, oral cavity, nasopharynx, uvea, leptomeninges and inner ear. In the normal human esophagus, scattered melanocytes may occur at the epithelio-stromal junction. In 1963, Dela Pava first described pre-existing esophageal melanocytes found in 4 out of 100 autopsies and found that they are not related to esophageal disorders[1].

In the normal esophagus, the number of intramucosal melanocytes is low and their presence can easily be overlooked, but many pathologic conditions can increase the number of melanocytes at the epithelio-stromal junction[4], suggesting that proliferation of melanocytes is based on pre-existing melanocytes in the interface between epithelium and underlying stroma. However, the proliferation of melanocytes might also arise from the scattered stromal neuroectodermal cells or from pluripotent epithelial stem cells[2]. The proliferation of melanocytes is rarely observed with an estimated incidence of about 0.07%-0.15% in patients undergoing endoscopy[3]. Results of a recent study[2] and our case, however, indicate that melanocytes are much more frequently seen in association with reactive changes in the squamous epithelium, such as chronic esophagitis. Moreover, melanocytes seem to be more frequently found in carcinoma specimens than in unselected autopsy material, which supports the notion that melanocytes may develop due to the long-standing inflammatory irritation of the mucosa. Our patient had a 30-year hist0ry of reflux, soda, smoking and alcohol which might indicate that esophageal BSC and proliferation of melanocytes are a general tissue reaction pattern in response to acid, basic and noxious stimuli. Hair follicles in the esophagus have not been reported up to now and may be due to the tissue reaction to the stimuli too, suggesting that melanocytes and hair follicles might develop from pluripotent epithelial stem cells. Up to now, no report is available on the association between esophageal BSC and hair follicles. Melanocytic nevi are uncommonly seen in esophageal mucosa. To our knowledge, only two cases of blue nevus in the esophagus are reported[5]. The blue nevus may be derived from the aboriginal melanocytes or pluripotent epithelial stem cells, and may be transformed into melanoma. What physiological and/or pathologic potential the hair follicles and blue nevus have in the esophageal mucosa needs to be further investigated.

The present case is very unusual because not only melenocytes and hair follicles proliferate in esophagus but also are associated with esophageal BSC and gastric stromal tumor. The epidemiology and etiology remain uncertain, although esophageal melanocytes are mostly located in the middle and lower thirds of the esophagus[6–9]. The intrinsic pathogenesis underlying these pathological changes in the gastrointestinal tract remains largely a mystery.

| 1. | De La Pava S, Nigogosyan G, Pickren JW, Cabrera A. Melanosis of the esophagus. Cancer. 1963;16:48-50. |

| 2. | Ohashi K, Kato Y, Kanno J, Kasuga T. Melanocytes and melanosis of the oesophagus in Japanese subjects--analysis of factors effecting their increase. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1990;417:137-143. |

| 3. | Yamazaki K, Ohmori T, Kumagai Y, Makuuchi H, Eyden B. Ultrastructure of oesophageal melanocytosis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1991;418:515-522. |

| 4. | Kreuser ED. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1979;385:49-59. |

| 5. | Lam KY, Law S, Chan GS. Esophageal blue nevus: an isolated endoscopic finding. Head Neck. 2001;23:506-509. |

| 6. | Mori A, Tanaka M, Terasawa K, Hayashi S, Shimada Y. A magnified endoscopic view of esophageal melanocytosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:479-481. |

| 7. | Yamamoto O, Yoshinaga K, Asahi M, Murata I. A Laugier-Hunziker syndrome associated with esophageal melanocytosis. Dermatology. 1999;199:162-164. |

| 8. | Jones BH, Fleischer DE, De Petris G, Heigh RI, Shiff AD. Esophageal melanocytosis in the setting of Addison's disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:485-487. |

| 9. | Walter A, van Rees BP, Heijnen BH, van Lanschot JJ, Offerhaus GJ. Atypical melanocytic proliferation associated with squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the esophagus. Virchows Arch. 2000;437:203-207. |