Published online Mar 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i12.1881

Revised: October 31, 2004

Accepted: November 29, 2004

Published online: March 28, 2005

Solitary non-parasitic liver cysts are being increasingly diagnosed due to the increased use of abdominal sonography. The majority of solitary liver cysts are asymptomatic; however, there are some complications which include infection, perforation, spontaneous hemorrhage, obstructive jaundice and neoplastic degeneration. In some cases a cystic liver lesion may mimic a tumor and is difficult to differentiate with standard imaging studies or fine needle aspiration cytology. Here in, we report a case of adenocarcinoma arising in a solitary hepatic cyst complicated with Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. High levels of CEA in the cyst fluid levels suggested malignancy, which was confirmed by pathology of the resected specimen.

- Citation: Lin CC, Lin SC, Ko WC, Chang KM, Shih SC. Adenocarcinoma and infection in a solitary hepatic cyst: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(12): 1881-1883

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i12/1881.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i12.1881

Intra-hepatic cysts are generally classified as congenital, traumatic, infectious, or neoplastic. The incidence of solitary hepatic cysts in the population at large has not been defined[1]. Adenocarcinoma arising in a solitary hepatic cyst is extremely rare, with only seven cases having been reported in the literature[2]. We report a patient with adenocarcinoma arising in a non-parasitic solitary hepatic cyst complicated with Klebsiella pneumoniae infection.

A 67-year-old male was admitted in November 2002 complaining of anorexia and upper quadrant pain for half a month. Over the previous three months, he had noted abdominal distention and about a 2 kg weight loss. His past medical history was significant for gouty arthritis and DM with chronic renal disease. Abdominal echo performed about two years ago in another medical center had found an egg-sized solitary hepatic cyst.

On admission, the patient appeared ill and had a low grade fever (37.5 °C). His abdomen was distended, and there was right upper quadrant tenderness without muscle guarding. Laboratory tests showed a normocytic anemia with a Hb of 105 g/L, white cell count 9.5×109/L with 56% neutrophils and 28% lymphocytes, serum total bilirubin 6.8 µmol/L, alkaline phosphatase 2.1 nkat/L, aspartate aminotransferase 0.32 µkat/L, alanine aminotransferase 0.41 µkat/L, creatinine 398 µkat/L, and uric acid 655 µmol/L. The serum levels of CEA (4.6 µg/L) and AFP (3.5 µg/L) were normal, but that of CA19-9 (44.3 kU/L) was mildly increased.

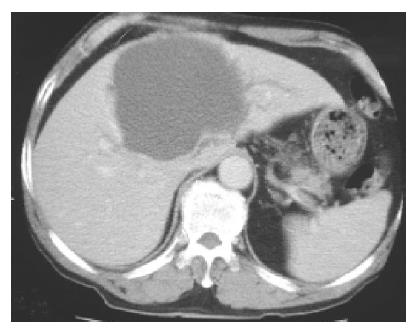

An abdominal ultrasound examination showed a solitary hepatic cyst about 10 cm×12 cm extending from the left liver segment 4 to the right liver segments 5 and 8. The cyst was filled with homogenous hyper-echoic material (Figure 1). There were no visible renal or pancreatic cysts. Our differential diagnosis based on the ultrasound appearance included infected hepatic cyst, hemorrhage into a cyst, or cystic tumor. Using echo guidance, we aspirated about 500 mL of cloudy, mucoid material. There was no foul smell to the fluid. The cyst decreased in size after aspiration. The fluid had numerous white cells with a neutrophil predominance, and a culture grew Klebsiella pneumoniae, consistent with a diagnosis of infected hepatic cyst. Although cytology was negative, tumor markers in the cystic fluid were increased (CEA 1093 µg/L, CA19-9 14237 kU/L). Despite repeated echo-guided aspiration, the cyst again grew to the previous size, with persistent elevation of CEA (835 µg/L) and CA19-9 (10661 kU/L) in the cystic fluid. Computed tomography showed a huge cystic space-occupying lesion with the largest diameter about 10 cm located in liver segments S8, S4 and S5. The mass caused mild intra-hepatic duct dilatation (Figure 2). Although we continued to suspect a simple hepatic cyst, we could not exclude a cystic biliary tumor. After echo-guided fluid aspiration, a T2-weighted liver MR image revealed a mass lesion consisting of mostly fluid density. The lower portion of this lesion, however, had low signal intensity suggestive of hemorrhage or a cystic tumor (Figure 3).

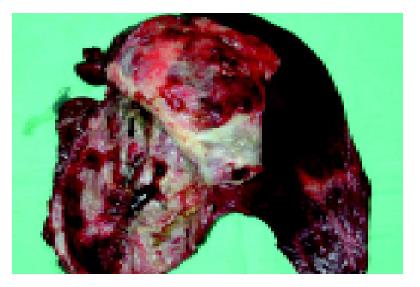

Given the progressive nature of the lesion plus the high levels of tumor markers in the fluid, malignancy was increasingly likely. The patient therefore underwent an exploratory laparotomy. A 10 cm×10 cm×10 cm cystic lesion containing turbid fluid was found in segments 4, 5, and 8 of the liver. The cyst was aspirated and then opened. Several dark red slightly papillary lesions and small dome-shaped nodules were found on the inner surface (Figure 4). Frozen section of a small portion of the cystic wall containing one nodule was reported as benign with only an inflammatory cell infiltrate. However, in view of the concern that this was not simply a benign cyst, an extended left lobectomy was performed.

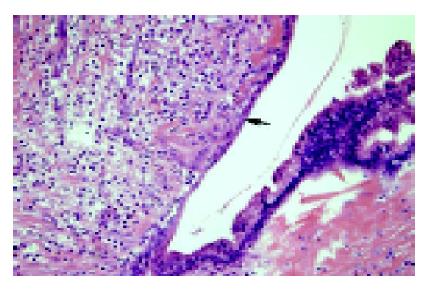

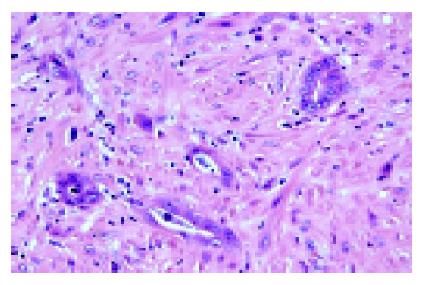

After formalin fixation, the cystic wall measured 0.2-0.6 cm in thickness. The internal surface varied from smooth to rough with areas of hemorrhage and several dome-shaped nodules on the inner surface. No bile ducts were found communicating with the cyst. Histologically, the cystic wall was lined by a single layer of biliary epithelium with focal proliferation in a slight papillary formation. There was mild nuclear atypia (Figure 5). In the nodular areas, there were scattered small round or angulated glandular structures and small cords. Some individual plump epithelial cells were noted with nuclear atypia, hyperchromatism. On larger magnification, these appeared to be infiltrating malignant cells (Figure 6). Immunostaining for CK was present not only in the luminal border, but also in the cytoplasm. The cells had increased cytoplasmic CEA and nuclear Ki-67 immunoreactivity. The neoplastic cells were confined within the cystic wall. The final pathology diagnosis was a solitary biliary cyst with focal adenocarcinomatous change. The patient had an uneventful post-operative course and has been followed for two years with no evidence of tumor recurrence.

Adenocarcinoma coexisting with solitary liver cysts is a distinct entity different from liver cystadenocarcinoma[2]. Azizah and Paradinas reported two adenocarcinomas coexisting with developmental liver cysts in 1980. Another five cases in the previous literature are considered to be adenocarcinoma arising in solitary cysts[2]. Willis described one case in a 27-year-old women in 1943, and Cruickshank and Sparshott reported two cases of cystic tumors in 1971[2,3]. Okuda et al, found simple cysts in two of their 57 cases of intra-hepatic bile duct carcinoma in 1977[3,4]. In none of these patients, however, there was an infection as complicated as that described in our case.

It is difficult to distinguish cystic focal liver lesions on imaging. Simple (bile duct) cysts, biliary cystadenoma, cystadenocarcinoma, cystic subtypes of primary liver neoplasms, cystic metastases, pyogenic and amebic abscesses, intra-hepatic hydatid cyst, extra-pancreatic pseudocyst, and intra-hepatic hematoma and biloma may all be confused with one another[5]. Our patient had only a low grade fever, with a normal white cell count and no edema or peripheral enhancement of the liver lesion on CT. It was only after echo-guided aspiration that infection was demonstrated in the cyst. Neoplasms in congenital cysts of the liver are very rare[1,6]. We suspected a malignant cystic tumor in our patient because the cyst was growing and the cystic fluid contained a high level of CEA. The findings were not compatible with biliary cystadenocarcinoma, which usually has internal separation and an irregular border between the adjacent hepatic parenchyma on CT[5]. A cystic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma was suspected, but these lesions usually have a definite irregular mass or peripheral enhancement on CT. In addition, bile ducts communicate with the cyst in cholangiocarcinoma, which was not the case in our patient’s cyst[7].

Although preoperative differentiation between simple cysts and malignant cystic tumors can be difficult, an attempt must be made to do so because the management for each is different. Fine needle aspiration cytology has rarely succeeded in yielding a preoperative diagnosis. For this reason, Marnerite and Alan studied CEA and CA19-9 levels in cystic lesions and found elevated CEA (>600 µg/L) in the fluid from biliary cystadenoma, cystadenocarcinoma, and pseudocystic metastatic carcinoma[8]. Horsmans et al[9], reported that cystic CA19-9 values were five times higher in cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma than in benign lesions. In our case, the high CEA and CA19-9 in the cystic fluid suggested malignancy.

Spontaneous infection of a hepatic cyst occurs rarely; in this case, the cause may be due to DM with renal insufficiency. The standard treatment when it does occur is drainage, which may both relieve the patient’s symptoms and lead to a definitive diagnosis of the cystic mass. We did consider percutaneous drainage in our patient, but because we were concerned about possible malignancy, we opted for surgery instead to avoid tumor seeding along the drainage tract[10].

Although the ideal is to make a definitive diagnosis preoperatively, for the reasons noted above, this is not always possible based on imaging and tumor markers alone[11]. Intra-operative pathology as well as the examination and surgeon’s gross examination are thus extremely important, as the findings may influence the type of procedure done. For example, extensive lymph node dissection is required for cholangiocarcinoma.

Adenocarcinomas from most organs have CEA immunoreactivity. In low-grade malignant tumors, CEA immunoreactivity is membrane bound, while in high-grade lesions, immunoreactivity is seen in the cytoplasm. However, because CEA immunoreactivity has also been demonstrated in a variety of normal tissues, it is not pathognomonic for malignancy.

In conclusion, an accurate diagnosis of cystic lesions of the liver that do not appear to be straightforward simple cysts remains problematic. Echo-guided fine needle aspiration may be a valuable method for differential diagnosis. In patients with symptomatic solitary liver cysts of uncertain etiology, liver resection should be considered, as one-fourth of such lesions might be malignant.

| 1. | Witzleben C. Cystic diseases of the liver. Hepatology: A Textbook of Liver Disease. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co 1996; 1631. |

| 2. | Azizah N, Paradinas FJ. Cholangiocarcinoma coexisting with developmental liver cysts: a distinct entity different from liver cystadenocarcinoma. Histopathology. 1980;4:391-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (75)] |

| 3. | Cruickshank AH, Sparshott SM. Malignancy in natural and experimental hepatic cysts: experiments with aflatoxin in rats and the malignant transformation of cysts in human livers. J Pathol. 1971;104:185-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 4. | Okuda K, Kubo Y, Okazaki N, Arishima T, Hashimoto M. Clinical aspects of intrahepatic bile duct carcinoma including hilar carcinoma: a study of 57 autopsy-proven cases. Cancer. 1977;39:232-246. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mortelé KJ, Ros PR. Cystic focal liver lesions in the adult: differential CT and MR imaging features. Radiographics. 2001;21:895-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (74)] |

| 6. | Arai H, Nagamine T, Suzuki H, Shimoda R, Abe T, Yamada T, Takagi H, Mori M. Simple liver cyst with spontaneous regression. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:755-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (73)] |

| 7. | Lee SK, Choi BI, Cho JM, Han JK, Kim YI, Han MC. Cystic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: sonography and CT. Abdom Imaging. 1995;20:131-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (75)] |

| 8. | Pinto MM, Kaye AD. Fine needle aspiration of cystic liver lesions. Cytologic examination and carcinoembryonic antigen assay of cyst contents. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:852-856. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Horsmans Y, Laka A, Gigot JF, Geubel AP. Serum and cystic fluid CA 19-9 determinations as a diagnostic help in liver cysts of uncertain nature. Liver. 1996;16:255-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (74)] |

| 10. | Kaneko T, Nakao A, Oshima K, Iizuka A. Rapid progression of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after drainage of large cystic lesions: report of a case. Surg Today. 2000;30:1049-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (76)] |

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK