©The Author(s) 2025.

World J Gastroenterol. Dec 7, 2025; 31(45): 112618

Published online Dec 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.112618

Published online Dec 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.112618

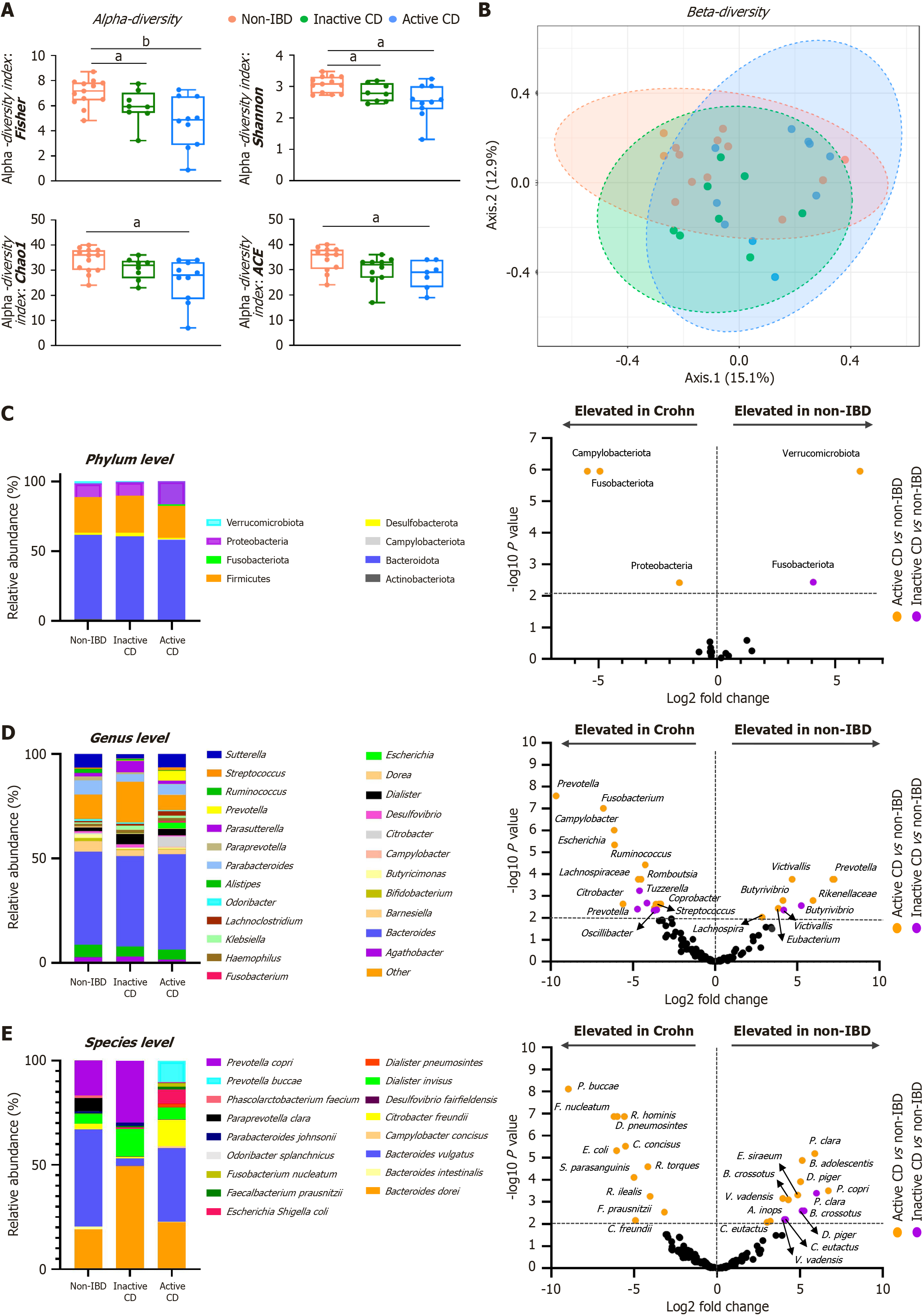

Figure 1 Microbiota composition and diversity in active and inactive Crohn’s disease and non-inflammatory bowel diseases subjects.

A: Alpha diversity analysis using the Fisher, Shannon, Chao1, and ACE diversity indices for each 16S rRNA dataset. Statistical significance was determined using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Mann-Whitney U test. aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01; B: Principal coordinates analysis based on the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index, illustrating beta diversity differences among study groups; C-E: Taxonomic differences between groups: Bar charts (left panels) represent the mean relative abundances of amplicon sequence variants, while volcano plots (right panels) highlight significantly different taxa between Crohn's disease patients and non-inflammatory bowel diseases individuals at various taxonomic ranks: Phylum (C), genus (D), and species (E) levels. CD: Crohn’s disease; IBD: Inflammatory bowel diseases.

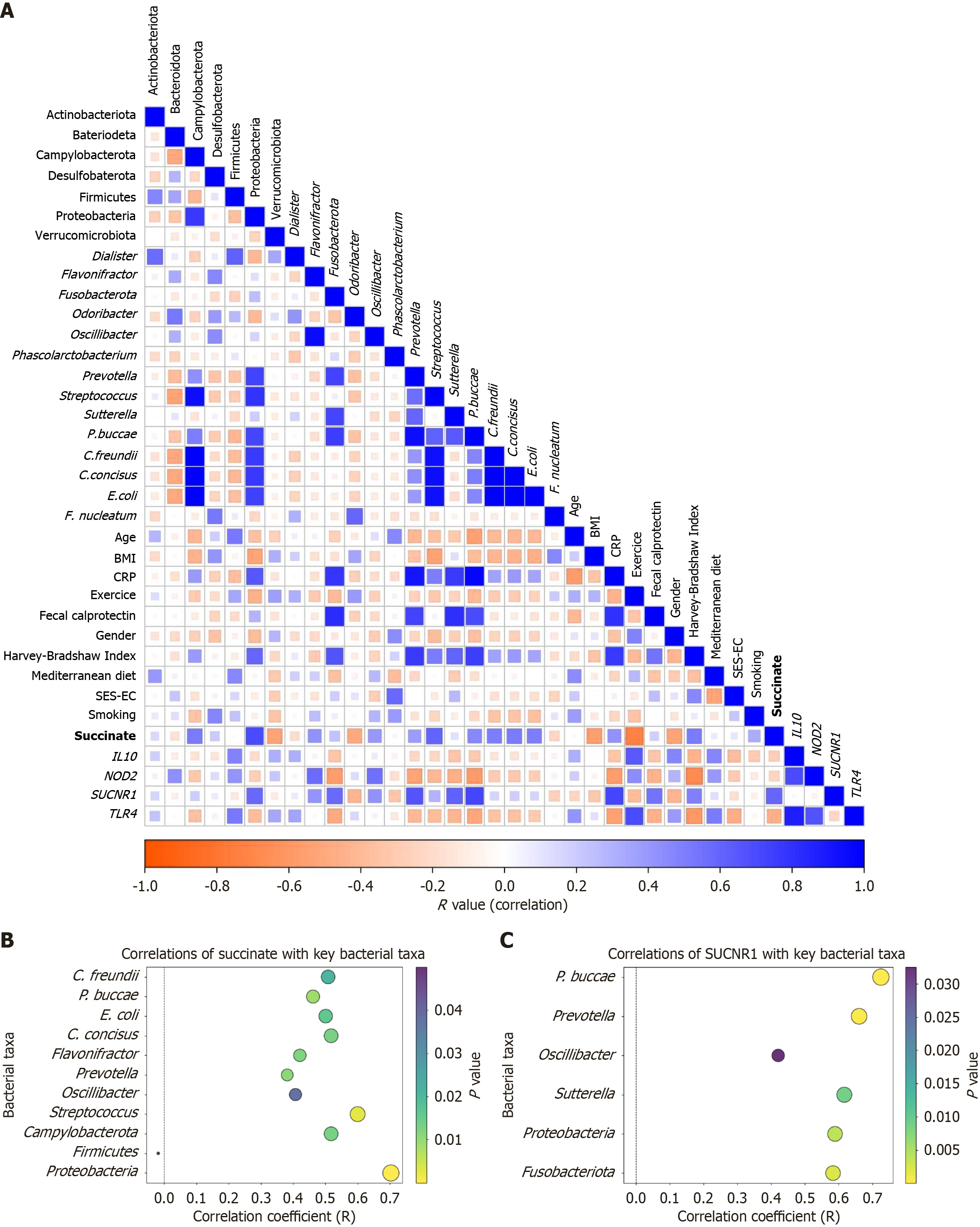

Figure 2 Correlation between gut microbiota metabolite succinate, microbial composition, and inflammatory markers.

A: Correlogram displaying Pearson’s correlation coefficients among succinate levels, microbial relative abundances, and clinical and biological parameters in the study cohort (n = 31); B: Correlation between circulating succinate levels and specific microbial taxa; C: Correlation between the succinate receptor 1 and specific microbial taxa. SUCNR1: Succinate receptor 1.

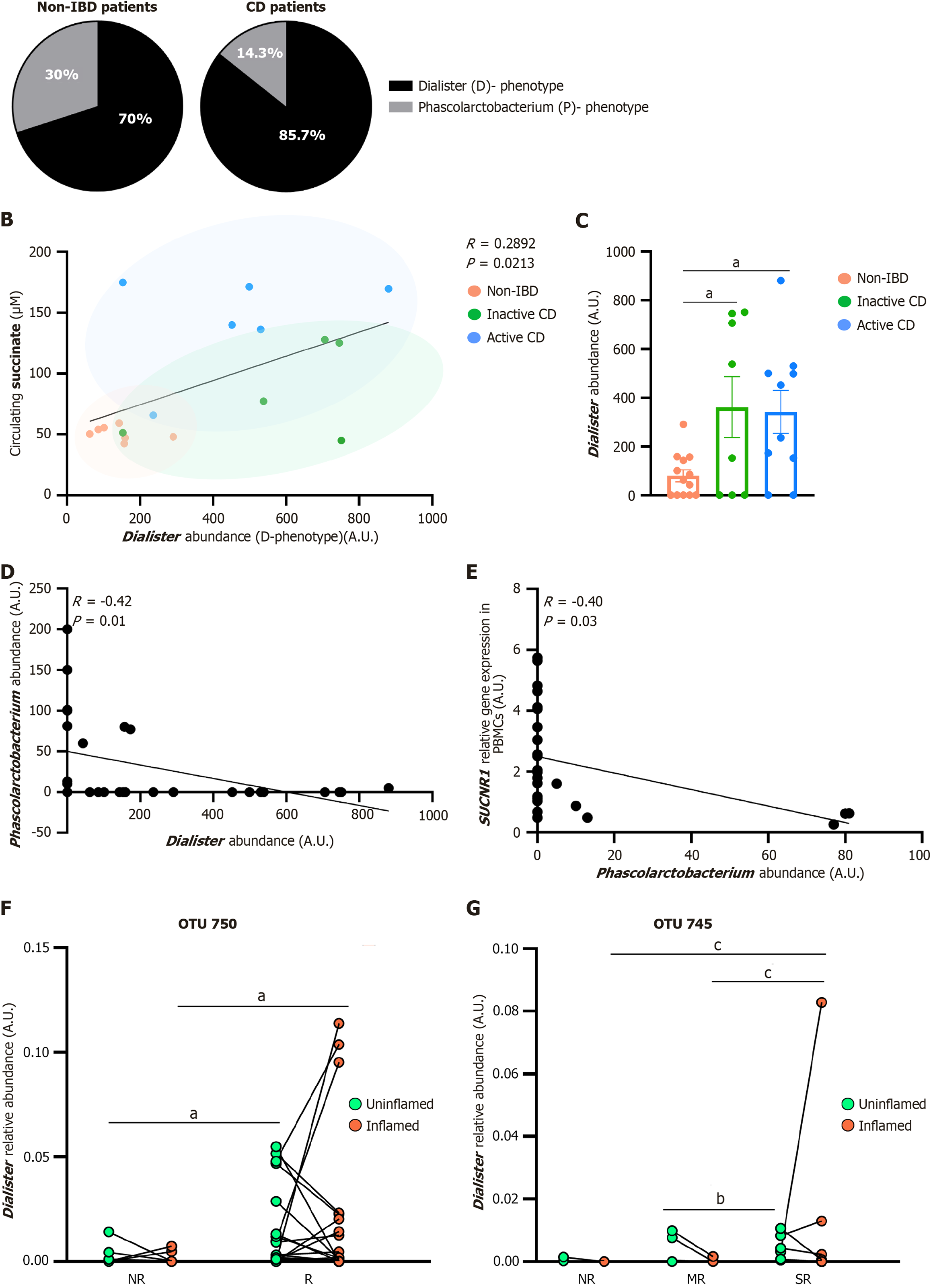

Figure 3 Dialister abundance associates with disease activity and postoperative recurrence in Crohn’s disease.

A: Classification of individuals into distinct “succinotypes” based on the relative abundances of Dialister and Phascolarctobacterium in Crohn’s disease (CD) and non-inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) subjects; B: Significant negative correlation between plasma succinate levels and Dialister abundance, a slow succinate-consuming genus (Pearson’s ρ, P value indicated in the figure); C: Comparison of Dialister abundance across active CD, inactive CD, and non-IBD subjects. aP < 0.05 vs non-IBD. Statistical analysis: Kruskal-Wallis test followed by pairwise Mann-Whitney U tests; D: Negative correlation between Dialister and Phascolarctobacterium abundances within the cohort (Pearson’s ρ); E: Negative correlation between Phascolarctobacterium abundance and succinate receptor 1 gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Pearson’s ρ); F: Mucosal Dialister operational taxonomic unit 750 levels distinguish non-recurrent from recurrent CD patients in uninflamed tissue from the validation cohort; G: Mucosal Dialister (operational taxonomic unit 745) abundance in inflamed mucosa differentiates among non-recurrent, mild-recurrent, and severe recurrent CD patients. Statistical significance was assessed using DESeq2 on non-transformed count data: aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01; cP < 0.001, as indicated in the panels. CD: Crohn’s disease; IBD: Inflammatory bowel diseases; OTU: Operational taxonomic unit; SUCNR1: Succinate receptor 1; NR: Non-recurrent; R: Recurrent; MR: Mild-recurrent; SR: Severe recurrent.

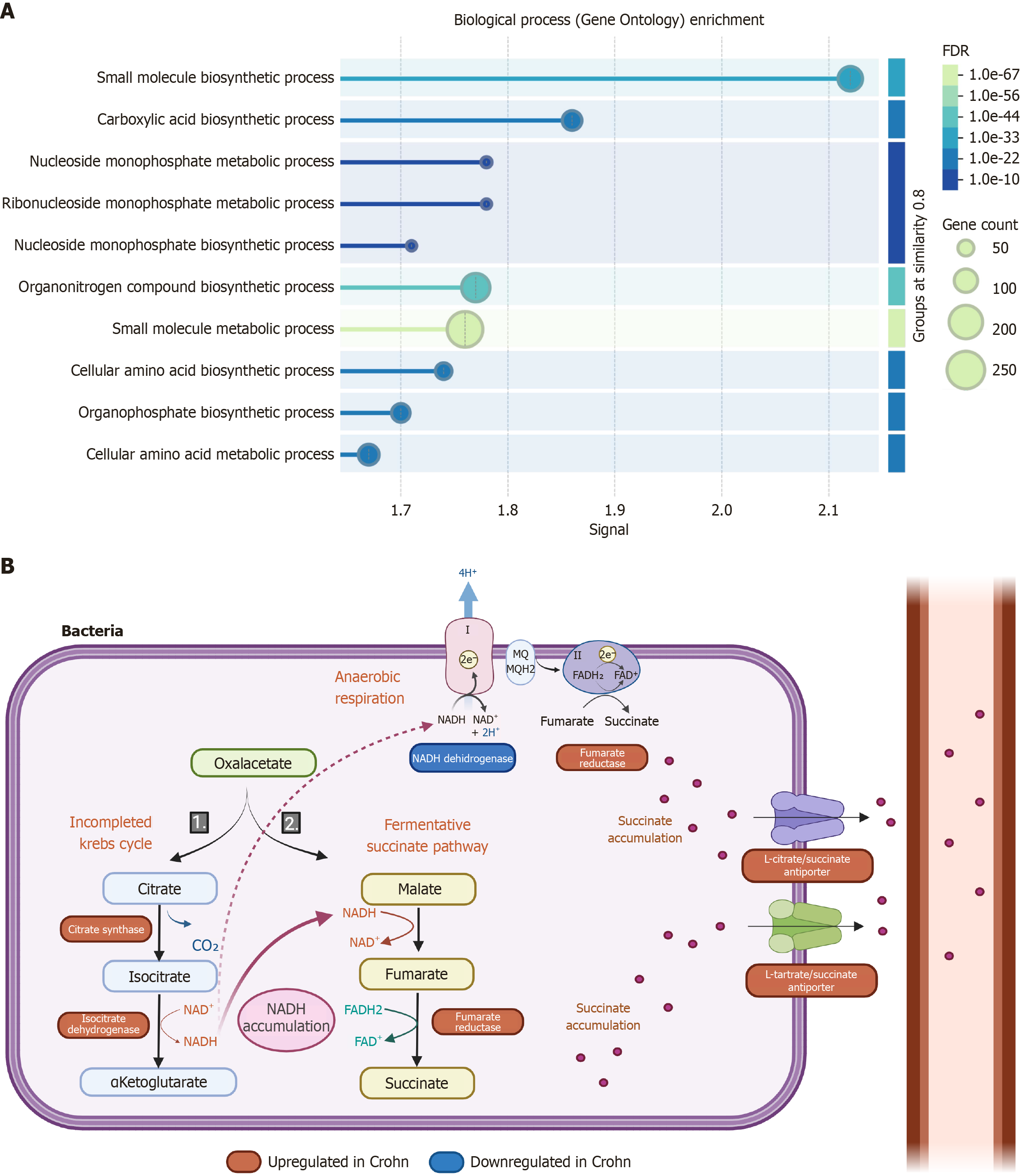

Figure 4 Functional analysis reveals succinate as a key metabolite associated with microbial dysbiosis in Crohn’s disease.

A: Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of microbial functions reveals a significant increase in carboxylic acid biosynthesis pathways in faecal microbiota from active Crohn’s disease (CD) patients compared with non-inflammatory bowel diseases controls (false discovery rate = 1 × 10-44), with succinate emerging as a central metabolite; B: Schematic representation of the main metabolic pathways active in strict anaerobic gut bacteria in CD patients. These bacteria exhibit upregulation of glycolytic enzymes and of specific enzymes of the (incomplete) tricarboxylic acid cycle - namely citrate synthase and isocitrate dehydrogenase - leading to increased NADH production. In the context of reduced NADH dehydrogenase activity, the excess NADH is diverted towards fermentative and anaerobic respiratory pathways, favouring succinate production. Fumarate reductase, an enzyme responsible for reducing fumarate to succinate, is also upregulated. Additionally, transporters such as L-citrate/succinate and L-tartrate/succinate are significantly increased, promoting succinate export from the bacterial cell. This metabolic reprogramming reflects adaptations typical of strict anaerobes and may contribute to the accumulation of microbial-derived succinate observed in CD. Figure created with BioRender.com. FDR: False discovery rate.

- Citation: Boronat-Toscano A, Queipo-Ortuño MI, Monfort-Ferré D, Suau R, Vañó-Segarra I, Valldosera G, Cepero C, Astiarraga B, Clua-Ferré L, Plaza-Andrade I, Aranega-Martín L, Cabrinety L, Abadia de Barbarà C, Castellano-Castillo D, Moliné A, Caro A, Domènech E, Sánchez-Herrero JF, Benaiges-Fernandez R, Fernández-Veledo S, Vendrell J, Ginés I, Sumoy L, Manyé J, Menacho M, Serena C. Dialister-driven succinate accumulation is associated with disease activity and postoperative recurrence in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(45): 112618

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i45/112618.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i45.112618