Published online Dec 18, 2025. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v13.i4.108681

Revised: June 9, 2025

Accepted: December 10, 2025

Published online: December 18, 2025

Processing time: 242 Days and 2.3 Hours

Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) has been a cornerstone treatment for mild to moderate ulcerative colitis (UC), traditionally used to maintain remission. With the rise of advanced therapies (biologics and small molecules), the role of 5-ASA has come under renewed scrutiny. While earlier systematic reviews affirmed its efficacy compared to placebo, these did not account for the advent of advanced therapies.

To assess the efficacy and safety of oral 5-ASA in maintaining remission in quie

It was systematically searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library, alongside conference proceedings (European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation, British Society of Gastroenterology), for randomized controlled trials published between 2003 and 2024 in English. Eligible studies involved oral 5-ASA therapies for quiescent UC with a minimum treatment duration of six months. Outcomes included failure to maintain remission, adverse events, and serious adverse events (SAEs). Data were analyzed using Cochrane methods, with GRADE assessing evidence certainty.

From 44 studies (9967 participants), 5-ASA was superior to placebo in maintaining remission, with 37% of 5-ASA users relapsing at 6-12 months compared to 55% of placebo users [risk ratios (RR): 0.68; 95%CI: 0.61-0.76; high-certainty evidence]. SAEs were rare and comparable between groups (RR: 0.60; 95%CI: 0.19-1.84; low-certainty evidence). Comparative analyses suggested 5-ASA remains a viable option alongside advanced therapies, with notable differences in cost and safety profiles.

5-ASA remains effective and safe for maintaining remission in quiescent UC, even in the advanced therapy era. However, tailored approaches are needed to balance efficacy, safety, and cost in clinical practice. This study provides critical insights to guide therapeutic strategies and underscores the enduring relevance of 5-ASA.

Core Tip: Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) has long been a cornerstone treatment for maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis (UC). This systematic review and meta-analysis of 44 randomized controlled trials, involving nearly 10000 patients, demonstrates that 5-ASA is significantly more effective than placebo in sustaining remission in quiescent UC, with a favorable safety profile. Despite the emergence of advanced therapies such as biologics and small molecules, 5-ASA remains a viable and cost-effective option. These findings underscore the enduring relevance of 5-ASA and highlight the need for tailored therapeutic approaches in the modern management of UC.

- Citation: Mudege T, Soldera J. Reevaluating aminosalicylates role in maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis in the era of biologics. World J Meta-Anal 2025; 13(4): 108681

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v13/i4/108681.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v13.i4.108681

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease characterized by mucosal inflammation primarily affe

Management of UC requires a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies aimed at inducing and maintaining remission. First-line treatments typically involve 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) compounds for mild to moderate disease, with corticosteroids reserved for acute flares[4]. In refractory cases, advanced therapies such as immunomodulators and biologics—including tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors, integrin inhibitors, and interleukin inhibitors—are employed[4-7]. Small molecule agents, notably Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, offer an oral alternative for moderate-to-severe UC[8]. Despite the development of these advanced therapies, 5-ASA remains central to treatment due to its established efficacy, safety profile, and longstanding use in maintaining remission[9]. The mechanism of action of 5-ASA involves inhibition of prostaglandin and leukotriene synthesis, reduction of leukocyte migration, and scavenging of free radicals, with its activity being predominantly topical[9,10].

Remission in UC is defined across several dimensions: Clinical remission (absence of symptoms), endoscopic remission (normal or near-normal mucosa), histologic remission (minimal or no microscopic inflammation), and biochemical remission (reduced inflammatory markers)[11-14]. Achieving deep remission—a composite of these measures—is critical for minimizing flare-ups, complications, and the risk of colorectal cancer[1,13,14]. Relapse, the re-emergence of symptoms following remission, is influenced by factors such as non-adherence to maintenance therapy, infections, psychological stress, dietary triggers, and gut dysbiosis[1,15-18]. Management of relapse requires tailored interventions, with mild flares often managed by escalating 5-ASA dosages, while moderate to severe episodes may necessitate corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, or biologic agents[4,15].

The rationale for this systematic review and meta-analysis is rooted in ongoing debates regarding the necessity of continuing 5-ASA therapy in patients with quiescent UC in the era of advanced therapies. Recent evidence indicates that while 5-ASA is effective for maintaining remission, its benefit when combined with biologics or small molecules remains uncertain[19-21]. Relapse rates following therapeutic de-escalation remain substantial, underscoring the need for further investigation into optimal maintenance strategies[22-26]. This review aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral 5-ASA compared with placebo and advanced therapies for sustaining remission in UC, addressing a critical gap in the current treatment paradigm.

A protocol was developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2024 guidelines[27,28] and registered with PROSPERO ID 1036484. Criteria for inclusion were defined a priori. Although the original intent was to include comparisons involving advanced therapies, no eligible randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing 5-ASA with biologics or small molecules were identified. Therefore, the review focuses on comparisons among 5-ASA regimens and placebo.

Study design: We included only prospective, RCTs with a parallel-group design and a minimum intervention period of six months.

Participants: Eligible studies enrolled adult participants (≥ 18 years) with mild-to-moderate UC in remission, defined by guideline-updated Truelove–Witts criteria and confirmed using Mayo score[4].

Interventions: Trials were required to evaluate oral 5-ASA used for maintenance of remission in UC, in comparison with either placebo or advanced therapeutic agents.

Outcomes: Primary outcome: Clinical or endoscopic relapse, according to the definitions provided by each individual study.

Secondary outcomes: Clinical or endoscopic remission rates; adherence to assigned treatment; incidence of adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs); and rates of treatment discontinuation or participant withdrawal due to AEs or other causes following study enrollment.

A thorough literature search was conducted across MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, the Cochrane IBD Specialized Register, and ClinicalTrials.gov, covering all records from database inception up to December 11, 2024. No filters were applied for language or publication type. The complete search strategy was as follows: (("advanced therapy"[All Fields] OR "biologics"[All Fields] OR "small molecules"[All Fields] OR "integrin inhibitors"[All Fields] OR "tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors"[All Fields] OR "tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors"[All Fields] OR "adalimumab"[MeSH Terms] OR "golimumab"[MeSH Terms] OR "infliximab"[MeSH Terms] OR "interleukin inhibitors"[All Fields] OR "ustekinumab"[MeSH Terms] OR "mirikizumab"[All Fields] OR "risankizumab"[All Fields] OR "vedolizumab"[MeSH Terms] OR "janus kinase inhibitors"[MeSH Terms] OR "JAK inhibitors"[All Fields] OR "tofacitinib"[MeSH Terms] OR "upadacitinib"[All Fields] OR "filgotinib"[All Fields] OR "sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator"[All Fields] OR "ozanimod"[MeSH Terms] OR "thiopurine"[MeSH Terms] OR "azathioprine"[MeSH Terms] OR "mercaptopurine"[MeSH Terms]) AND ("ulcerative colitis"[MeSH Terms] OR "ulcerative colitis"[All Fields]) AND ("remission"[All Fields] OR "quiescent"[All Fields]) AND ("5-aminosalicylic acid"[MeSH Terms] OR "5-ASA"[All Fields] OR "mesalazine"[All Fields] OR "mesalamine"[All Fields] OR "mesalasine"[All Fields] OR "5-aminosalicylates"[All Fields])).

Review articles and conference abstracts were also screened. Study selection was performed independently by two clinicians; discrepancies were resolved by consensus and, if necessary, by contacting original authors for clarifications on methodology and outcome measures.

Data were extracted independently using a standardized form and recorded on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis. Extracted data included baseline characteristics (e.g., sex, age, disease location, disease duration), details of the intervention (dose, route), comparators (placebo, active control), and pre-specified primary and secondary outcomes. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Studies were included for assessment only if published in English.

The risk of bias in each study was assessed using the Cochrane ‘Risk of Bias’ tool[29]. Domains evaluated included sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential sources of bias. Each domain was judged as ‘yes’ (low risk), ‘no’ (high risk), or ‘unclear’. The assessment was conducted independently by both authors, in consultation with a senior research methods consultant. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. Several studies were conducted with open-label or single-blind designs. The lack of double blinding in these trials introduces a potential for performance and detection bias, particularly in outcomes such as clinical relapse, which may be influenced by patient or investigator expectations.

For dichotomous outcomes, risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using a fixed-effect model, provided that participants, interventions, and outcomes were sufficiently similar. For continuous outcomes, either the mean difference or standardized mean difference with 95%CI was computed. Z scores were calculated when appropriate.

For multi-arm trials, the placebo group was split across comparisons to allow independent analysis[23,30]. In cross-over studies, only data before the first cross-over were used. For outcomes measured at multiple time points, fixed intervals for follow-up were predetermined. Recurring events were analyzed as the proportion of participants experiencing at least one event.

Missing dichotomous outcomes were analyzed on an ITT basis, assuming missing participants as treatment failures. For continuous outcomes, only data from completers were used without imputation.

Heterogeneity was evaluated using the χ² test (P < 0.10) and the I² statistic[29]. If significant heterogeneity was present, a random-effects model was employed. Reporting biases were assessed by comparing study protocols with final manuscripts; if protocols were unavailable, methods sections were compared with results. Funnel plots were planned for analyses including more than 10 studies.

Data were synthesized using Microsoft Excel and the R statistical environment, employing the meta and metafor packages. Planned comparisons included 5-ASA vs placebo, once-daily vs conventional dosing, and 5-ASA vs alternative 5-ASA formulations. Subgroup analyses were prespecified based on dosing regimens and specific 5-ASA compounds.

Sensitivity analyses excluded studies with a high risk of bias. The overall certainty of evidence was rated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach, considering risk of bias, indirectness, inconsistency, imprecision, and reporting bias[27-29]. Summary of findings tables were prepared for primary outcomes and selected secondary outcomes.

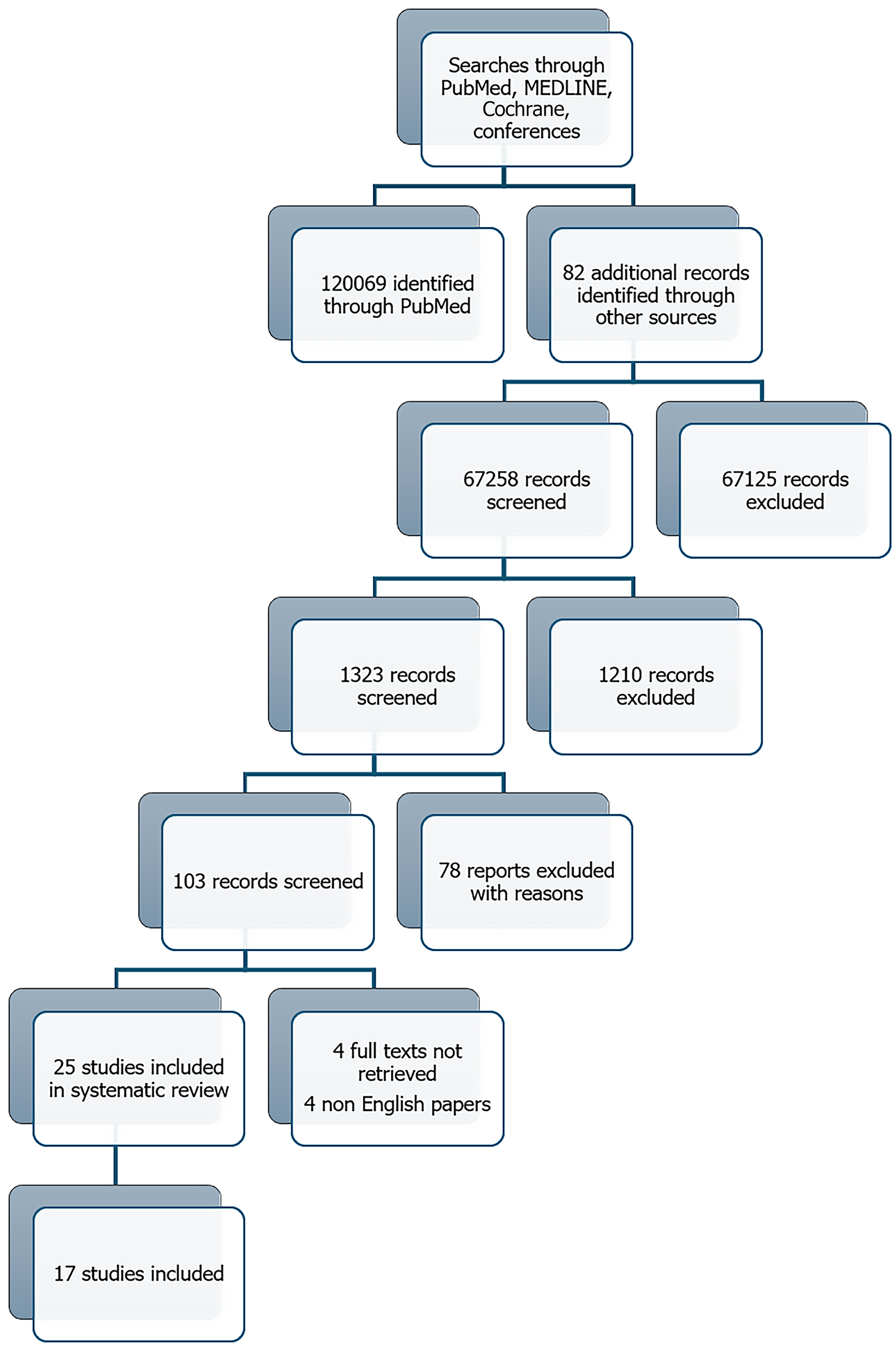

The literature search conducted on December 11, 2024 initially yielded 120069 records, with an additional 82 records were identified through reference list screening. This number reflects the use of broad search terms and multiple databases to ensure comprehensive coverage. However, we applied filters and automatic exclusions (e.g., by publication type and subject relevance) to improve specificity. After these refinements, and following duplicate removal, 2321 records remained for title and abstract screening. A total of 17 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis (totaling 5934 participants) evaluating oral 5-ASA maintenance treatment for quiescent UC were selected for full-text review (Figure 1), of which 14 were eligible for quantitative meta-analysis.

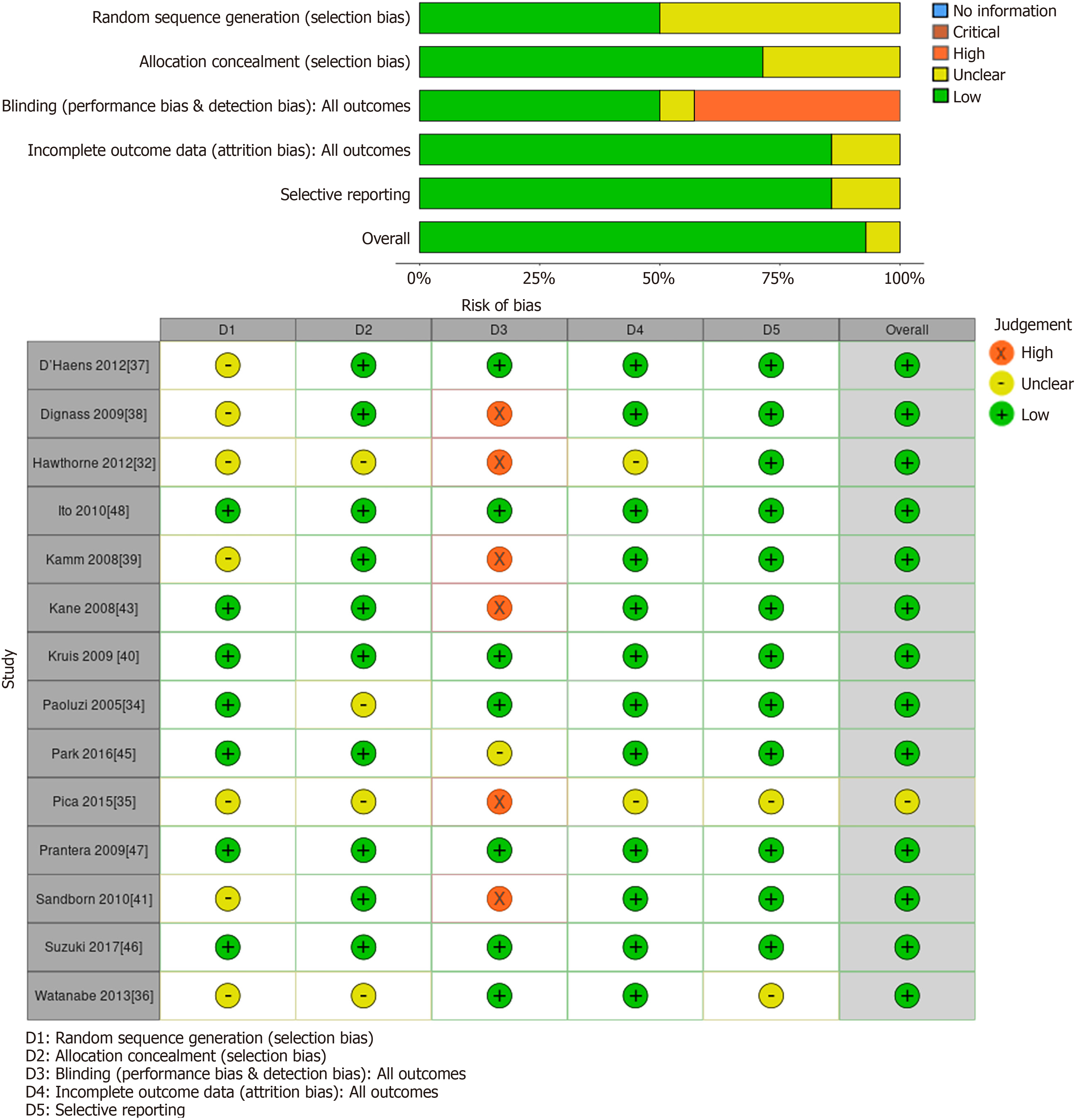

Allocation: Six studies did not describe the methods used for allocation concealment and were rated as unclear for this item[31-36]. The remaining studies were judged to have a low risk of allocation bias. Eleven studies[31-41] did not specify the method of randomization and were rated as unclear for randomization bias. The remainder of the studies were at low risk of randomization bias.

Blinding: Five trials adopted a single-blind methodology, in which the investigators responsible for evaluating outcomes were blinded to treatment allocation[32,38,41-43]. Two other studies followed an open-label approach, with both investigators and participants aware of the assigned interventions[35,39,44]. Notably, one of the open-label trials[39] and three single-blind trials[32,38,43] incorporated investigator-conducted endoscopy as an outcome measure, potentially limiting bias provided the endoscopist remained blinded. All remaining studies were considered to have a low risk of both performance and detection bias.

Two studies were rated as unclear for incomplete outcome data because the reasons for withdrawal were not adequately described[32,35].

Most studies were judged to be at low risk for selective outcome reporting. Kamm 2008, an open-label method might have influenced performance bias to reduced clinical relapse reporting. Sandborn 2010 single-blind method might have influenced detection bias due to a lack of baseline comparator or consideration of potential confounders. Additionally, no other potential sources of bias were identified (Table 1, Figures 2 and 3).

| Ref. | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding (performance bias & detection bias): All outcomes | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): All outcomes | Selective reporting | Other bias |

| D'Haens et al[37], 2012 | ? | + | + | + | + | + |

| Dignass et al[38], 2009 | ? | + | - | + | + | + |

| Hawthorne et al[32], 2012 | ? | ? | - | ? | + | + |

| Ito et al[48], 2010 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Kamm et al[39], 2008 | ? | + | - | + | + | + |

| Kane et al[43], 2008 | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| Kruis et al[40], 2009 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Paoluzi et al[34], 2005 | ? | ? | + | + | + | + |

| Park et al[45], 2016 | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Pica et al[35], 2015 | ? | ? | - | ? | ? | ? |

| Prantera et al[47], 2009 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Sandborn et al[41], 2010 | ? | + | - | + | + | + |

| Suzuki et al[46], 2017 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Watanabe et al[36], 2013 | ? | ? | + | + | ? | + |

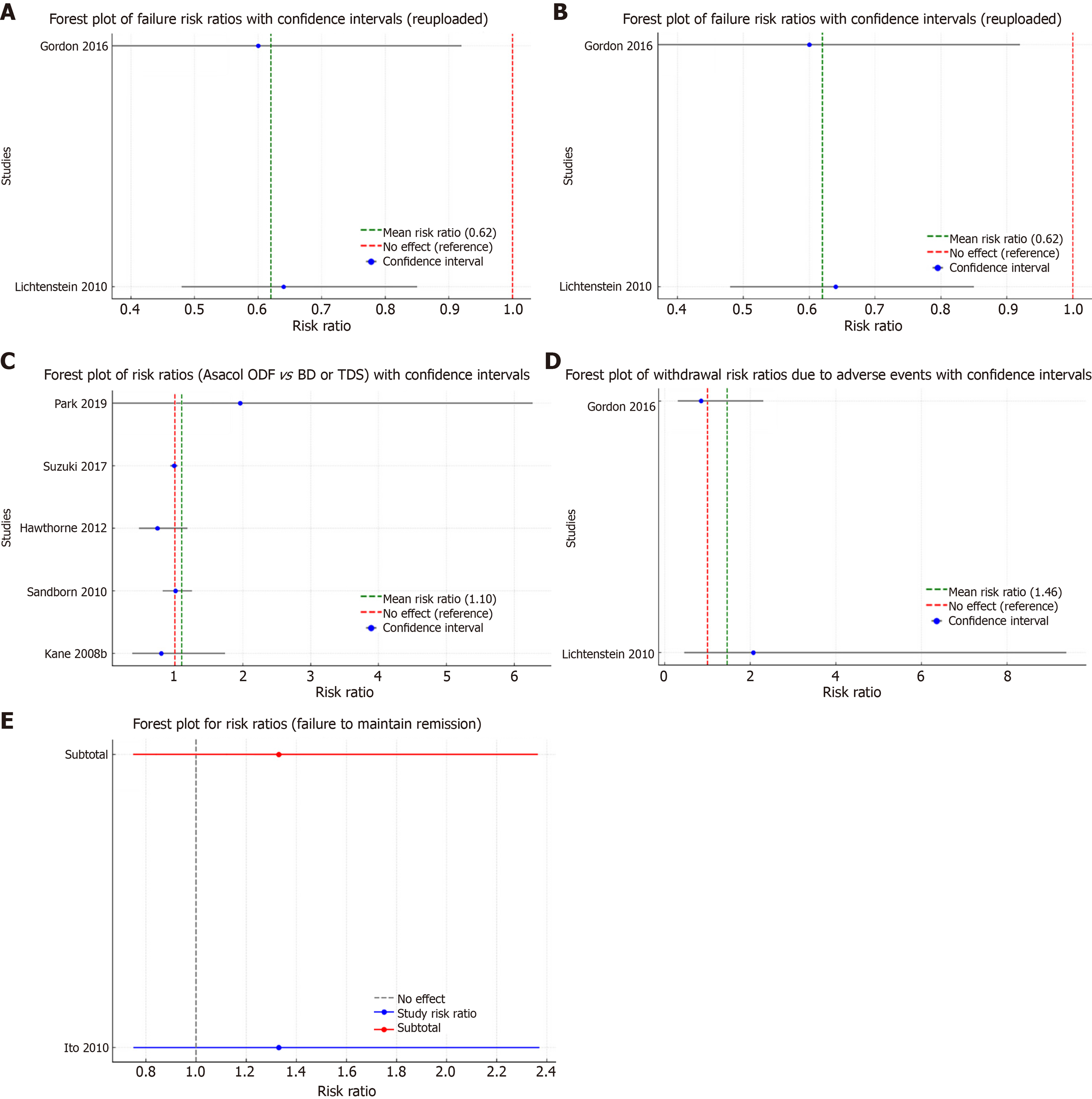

5-ASA vs placebo: Endoscopic or clinical relapse: Two trials (n = 562) reported outcomes regarding failure to maintain clinical or endoscopic remission at six to 12 months[31,33]. Relapse occurred in 26% (98/373) of 5-ASA participants vs 52% (98/189) of placebo participants (RR: 0.63, 95%CI: 0.50-0.79; I² = 10%; high-certainty evidence; Figure 2A).

AEs: Two studies (n = 458) reported that approximately 59% (220/373) of 59% (220/373) of 5-ASA participants and 63% (119/189) of placebo participants experienced at least one adverse event (RR 0.93, 95%CI: 0.81-1.07; χ² = 1.66, P = 0.20; I² = 0%; Z = -0.97, P = 0.33; Figure 2B), indicating no statistically significant difference[31,33]. Frequent adverse events reported across the studies comprised headache, nausea, abdominal discomfort, dyspepsia, abdominal distension, flu-like symptoms, rhinitis, diarrhea, and nasopharyngitis.

Serious AEs: Two studies (n = 562) observed that 1% (4/373) of 5-ASA participants experienced at least one SAE compared to 2% (4/189) in the placebo group (RR: 0.93, 95%CI: 0.81-1.07; I² = 0%; analysis 1.4)[31,33]. SAEs included UC exacerbation, acute pancreatitis, moderate ventricular dysfunction, esophagitis, and intestinal obstruction.

Withdrawals due to adverse events: Two studies (n = 458) reported withdrawals due to adverse events in 5% (18/373) of 5-ASA participants vs 4% (8/189) in placebo participants (RR: 1.12, 95%CI: 0.48-2.58; χ² = 0.92, P = 0.33; analysis 1.5)[31,33].

Withdrawals after study entry: One study (n = 498) reported exclusion or withdrawal after entry in 9% (18/209) of 5-ASA participants compared to 10% (18/189) of placebo participants (RR: 1.22, 95%CI: 0.59-2.53; I² = 0%; Z = 0.54, P = 0.60; analysis 1.7)[33].

Endoscopic or clinical relapse: Two trials (n = 1045) reported that 15% (85/524) of once-daily dosing participants relapsed compared to 18% (76/521) of conventional-dosing participants at six months (RR: 1.10, 95%CI: 0.83-1.46; I² = 0%; Figure 2C)[41,42]. Five trials (n = 2139) reported outcomes at 12 months to 13 months[32,41,43,45,46], with 8% (85/1020) relapse in once-daily dosing and 7% (77/1119) in conventional dosing (RR: 0.98, 95%CI: 0.91-1.06; χ² = 3.18, df = 6, P = 0.50; high-certainty evidence; analysis 2.2.1). A subgroup analysis for time-dependent mesalamine (Pentasa) favored once-daily dosing [28% (91/321) vs 75% (127/169); RR: 0.90, 95%CI: 0.60-0.93], while other formulations (MMX OD vs BD) showed no significant differences (analyses 2.2.2 and 2.2.3).

Adherence to medication regimen: Nine trials (n = 2306) reported adherence at study endpoints[32,36,38-40,42,43,45,47]. Non-adherence was 9% (106/1152) in the once-daily group compared to 7% (84/1154) in the conventional-dosing group (RR: 1.12, 95%CI: 0.85-1.46; I² = 57%; analysis 2.3.1). Notably, the Kamm 2008 trial contributed significant heterogeneity due to markedly lower adherence in once-daily dosing[39]. Hawthorne et al[32] reported higher compliance in the once-daily group (97.1%) compared to the thrice-daily group (85.5%) (analysis 2.3.2).

AEs: Eight studies (n = 3497) reported that 48% of once-daily dosing and 49% of conventional-dosing participants experienced at least one adverse event at six to 13 months (RR: 1.09, 95%CI: 0.68-1.77; χ² = 0.74, P = 0.94; analysis 2.5)[36-40,45-47].

Serious AEs: Six studies (n = 3196) indicated that 3% of once-daily participants experienced at least one SAE compared to 2% in conventional dosing (RR: 1.09, 95%CI: 0.68-1.77; χ² = 0.74, P = 0.95; Figure 2D)[38-40,45-47]. These included hospitalization due to disease relapse or complications, severe infections, and infrequent occurrences of pancreatitis and hypersensitivity reactions. Overall, the incidence of SAEs was low and comparable between the 5-ASA and control groups.

Withdrawals due to AEs: Eight studies (n = 4340) reported withdrawals due to AEs in 2% of once-daily and 2% of conventional-dosing participants (RR: 1.09, 95%CI: 0.68-1.77; χ² = 0.74; analysis 2.5)[36-41,46,47].

Withdrawals after study entry: Seven studies (n = 4340) found that approximately 15% of participants in both groups were excluded or withdrawn after entry (RR: 1.09, 95%CI: 0.68-1.77; χ² = 0.74, P = 0.94; analysis 2.5.2)[36-41,47]. One trial (Dignass 2009a) reported a notably higher withdrawal due to adverse effects in the once-daily group (43% vs 2%; RR: 5.34, 95%CI: 0.63-45.28).

Endoscopic or clinical relapse: One study (n = 130) compared various formulations of 5-ASA [e.g., balsalazide, time-dependent mesalamine (Pentasa), olsalazine] vs comparators (e.g., Asacol, Salofalk)[48]. Relapse rates were 31% (20/65) in the 5-ASA group and 23% (15/65) in the comparator group (RR: 1.33, 95%CI: 0.75-2.37; χ² = 0, P = 1; Z = 0, P = 0.35; Figure 2E).

Adherence: None of the studies in this comparison reported adherence data.

AEs: The same study reported that 95% of participants in both groups experienced at least one adverse event (RR: 1.00, 95%CI: 0.93-1.08; Z = 0; analysis 3.2)[48]. Reported adverse events included dyspepsia, abdominal pain, nausea, distension, diarrhea, headache, nasopharyngitis, respiratory infections, influenza-like disorder, and rash.

Serious AEs: No serious adverse events were reported in this study.

Withdrawals due to AEs: In the study[48,49], 5% (3/65) of the 5-ASA group were withdrawn due to adverse events compared to 2% (1/65) in the comparator group (RR: 3.00, 95%CI: 0.32-28.09; Z = 0.96, P = 0.34; analysis 2.7).

Withdrawals after study entry: One study reported that 28% (18/65) of participants in the 5-ASA group were excluded or withdrawn after entry vs 2% (1/65) in the comparator group (RR: 1.13, 95%CI: 0.63-2.01; Z = -0.33, P = 0.73; analysis 2.8)[48].

This systematic review confirms and refines the findings of previous meta-analyses by incorporating 17 studies with a total of 5934 participants[19,23]. Although the overall effect size is slightly smaller than that reported in the previous Cochrane review (17 studies vs 44 studies), the current review maintains adequate statistical power to support robust conclusions. Unlike the Cochrane review, which comprehensively assessed 5-ASA efficacy, our study places this evidence in the context of evolving treatment paradigms. While head-to-head RCTs comparing 5-ASA and advanced therapies are lacking, our findings remain relevant for populations where biologics and small molecules are not accessible, affordable, or clinically appropriate. The evidence demonstrates that oral 5-ASA preparations are effective for maintaining remission in quiescent UC, as the relapse rate in placebo-treated patients was approximately double that in those receiving 5-ASA. Furthermore, no significant differences in efficacy were observed between once-daily and conventional dosing regimens, indicating that dosing frequency does not impact the therapeutic effectiveness of 5-ASA. Similarly, comparisons among various 5-ASA formulations—such as time-dependent mesalamine (Pentasa), Asacol, Salofalk, balsalazide, and olsalazine—revealed no significant differences in relapse rates, although this conclusion is based on a single study[48,49].

The safety profile of 5-ASA is consistently favorable. The incidence of AEs, SAEs, and withdrawals due to AEs were low and did not differ significantly between 5-ASA and placebo groups, nor between once-daily and conventional dosing regimens. Gastrointestinal symptoms were the most commonly reported adverse events and the primary reason for study withdrawal. Adherence was also robust, with no significant impact of dosing frequency on patient compliance, likely attributable to the self-motivated nature of study participants and the rigorous monitoring implemented throughout the clinical trials[32,38-40,47].

The findings of this review are generalizable to a wide spectrum of individuals with mild-to-moderate UC, whether in active or quiescent phases. It provided a thorough evaluation of multiple treatment comparisons, including 5-ASA vs placebo, different 5-ASA dose ranges, and once-daily vs conventional dosing schedules. The evidence supporting relapse prevention was of moderate to high certainty, offering meaningful guidance for clinical decision-making[2,4,9]. Nonetheless, a significant evidence gap persists—specifically, the absence of prospective randomized trials assessing the impact of de-escalating from advanced therapies once remission has been achieved, an issue of considerable clinical importance.

In comparing 5-ASA with advanced therapies, including thiopurines, biologics, and small molecules, it is evident that while advanced therapies have revolutionized UC management, 5-ASA continues to offer comparable benefits in terms of remission maintenance in quiescent UC. Thiopurines such as azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine maintain remission rates of 60%-70% over one year, albeit with a need for close monitoring due to potential adverse effects[50,51]. Infliximab, as demonstrated in pivotal trials, provides durable remission, mucosal healing, and corticosteroid-sparing effects, thereby reducing colectomy rates[52,53]. Similarly, adalimumab has shown robust efficacy in achieving and sustaining remission, with the added convenience of subcutaneous administration that enhances patient adherence[54]. Emerging therapies, including small molecules like tofacitinib and upadacitinib, as well as novel agents such as ozanimod and etrasimod, offer additional options; however, their long-term safety profiles necessitate vigilant monitoring[13,54-58].

Overall, 5-ASA remains a safe and effective option for the maintenance of remission in patients with mild to moderate UC, supported by strong evidence of its efficacy and favorable safety profile. The comparable clinical significance of 5-ASA and advanced therapies, particularly regarding remission rates, suggests that 5-ASA continues to have a pivotal role in UC management. Nevertheless, the absence of direct head-to-head comparison studies between 5-ASA and advanced therapies warrants caution in interpretation. Future well-designed RCTs are needed to definitively elucidate the relative benefits of 5-ASA in patients who have achieved remission through either conventional or advanced therapies.

While this review focused exclusively on 5-ASA therapies, it is important to acknowledge that multiple biologics and small molecules have emerged as maintenance options in UC. Among anti-TNF agents, golimumab has demonstrated efficacy in the PURSUIT-M study, offering logistical convenience with a favorable immunogenicity profile[59,60]. Vedolizumab, a gut-selective anti-integrin agent, has shown corticosteroid-free remission and mucosal healing in GEMINI 1, with reduced systemic immunosuppression via α4β7-MAdCAM-1 inhibition[11,61,62]. Ustekinumab, targeting the IL-12/23 pathway, achieved durable remission in the UNIFI trial and may suit patients who fail anti-TNF or anti-integrin therapies[11,63,64].

New IL-23p19 inhibitors such as mirikizumab and risankizumab have demonstrated remission and mucosal healing in trials like LUCENT-2 and INSPIRE, with tolerable safety profiles[65-69]. Oral agents such as ozanimod and etrasimod, selective S1P modulators, showed remission in TRUE NORTH and ELEVATE UC, offering the advantage of oral administration[58,70,71]. Tofacitinib, a JAK inhibitor, has confirmed efficacy in the OCTAVE program but requires caution due to known risks[13,72,73]. These therapies reflect evolving strategies in UC management, yet none were evaluated in our meta-analysis. Therefore, the discussion is limited to contextualizing the continued relevance of 5-ASA within this expanding treatment landscape.

While head-to-head trials comparing 5-ASA to advanced therapies are lacking, indirect comparisons provide useful context. For example, golimumab achieved a 47% clinical remission rate at week 54 in the PURSUIT-M trial[59], vedolizumab showed sustained remission in 41.8% of patients in GEMINI 1[61], and ustekinumab achieved 44% remission at week 44 in UNIFI[63]. By contrast, our review found relapse rates in the 5-ASA arms ranging from 17%-40% depending on formulation and dosing. Although not directly comparable due to population and endpoint differences, these figures support the continued utility of 5-ASA in patients with mild-to-moderate disease or those unable to access advanced therapies.

In aggregate, these therapies reflect a paradigm shift towards individualized, mechanism-based treatment strategies in UC. Treatment selection should be guided by disease severity, prior therapeutic exposure, comorbidities, patient preference, and safety considerations. While anti-TNF agents remain foundational, newer biologics and small molecules provide alternatives that may reduce systemic risk or improve convenience. The shared goal across these agents is sustained corticosteroid-free remission, mucosal healing, and enhanced quality of life.

In the era of increasingly frequent combination advancedtherapy regimens—such as antiTNF agents with thiopurines or the addition of JAK inhibitors—the risk of infection or drugrelated gastrointestinal symptoms is amplified, making a meticulous differential diagnosis essential[74]. Before escalating or layering treatments, clinicians must distinguish IBD flares[75-77] from mimickers such as celiac disease[78-80], microscopic colitis[81], chronic and parasitic infections including tuberculosis, Cytomegalovirus, Blastocystis, Clostridioides difficile and Giardia[82-88], ingested foreign bodies[89], smallbowel or colonic neoplasms[90], pellagra[91], and druginduced diarrhoea from antibiotics, NSAIDs, or chemotherapeutics[92-94]. The presence of alarm features—unintentional weight loss, rectal bleeding, nocturnal symptoms, or a family history of colorectal cancer or IBD—should prompt targeted investigations (endoscopy, serologies, stool studies) to unmask the true etiology. Accurate diagnosis not only avoids unnecessary or potentially harmful therapies but also ensures that patients receive the most appropriate, mechanismbased intervention. Furthermore, recent case reports and systematic reviews have drawn attention to rare but severe complications in IBD—namely primary sclerosing cholangitis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome[95] and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis[96]—highlighting the necessity of a comprehensive diagnostic approach.

This review has several limitations that warrant consideration. Although a comprehensive search strategy was employed, publication bias cannot be excluded, particularly since most analyses included fewer than ten studies, limiting formal assessment via funnel plots. Several included trials were judged to be at unclear or high risk of bias in critical domains such as random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding. The lack of blinding in particular may have introduced performance and detection bias, especially for subjective outcomes like clinical relapse. Additionally, adherence to medication—a clinically important outcome—was not reported in any of the included studies, limiting insight into real-world effectiveness. This concern is amplified by known adherence challenges with 5-ASA regimens requiring multiple daily doses, which could further reduce effectiveness in routine clinical practice.

Clinical and methodological heterogeneity—including differences in study design, dosing regimens, and outcome definitions—limited the ability to pool data across studies and restricted subgroup comparisons (e.g., low- vs high-dose 5-ASA or once-daily vs conventional dosing). Subgroup analyses such as comparisons between specific 5-ASA formulations (e.g., Pentasa vs others) were underpowered due to the small number of contributing studies, and should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating rather than definitive. The use of a fixed-effects model, while appropriate given low statistical heterogeneity, may nonetheless underestimate uncertainty in the presence of clinical variability. Lastly, while dichotomous outcomes were analyzed using ITT principles, missing continuous data were not imputed, which may introduce attrition bias and affect the robustness of some estimates. These limitations collectively underscore the need for cautious interpretation of our findings and highlight the importance of future trials that report on adherence, apply robust blinding methods, and include head-to-head comparisons with advanced therapies to better reflect real-world treatment conditions.

Future research should focus on comparative effectiveness, real-world durability of response, and strategies for sequencing and combining therapies. Additionally, biomarker-driven approaches may refine patient stratification and improve response prediction, ultimately guiding clinicians towards a more tailored and efficacious management paradigm for UC.

This systematic review and meta-analysis supports the use of oral 5-ASA as an effective maintenance therapy for patients with quiescent UC, significantly reducing the risk of clinical or endoscopic relapse compared to placebo. Despite the emergence of advanced therapies, these findings affirm the continued relevance of 5-ASA in the maintenance of remission for mild to moderate UC. While the study design precludes direct comparison with biologics or small molecules, the consistent benefit and benign safety profile of 5-ASA support its role as a first-line maintenance agent—particularly in patients without high-risk features, those newly diagnosed, or in resource-limited settings where access to advanced therapies may be constrained.

The available evidence suggests a favorable safety profile, with no significant increase in adverse or serious adverse events. However, the overall strength of the evidence is tempered by methodological limitations in some included studies and the absence of adherence data. Future trials with standardized outcome measures, analyzing the risk of developing colorectal cancer, clearer reporting of methodology, and real-world adherence data are needed to strengthen the evidence base and inform optimal dosing strategies. The findings also highlight the need for future studies comparing de-escalation strategies and real-world outcomes in patients transitioning from advanced therapies, to clarify whether 5-ASA can maintain remission in this subset.

Until such data emerge, 5-ASA remains a cost-effective, safe, and effective option within the modern therapeutic armamentarium for UC—especially in patients for whom safety, cost, and accessibility are major considerations.

We extend our appreciation to the Faculty of Life Sciences and Education at the University of South Wales in association with Learna Ltd. for the Gastroenterology MSc program and their invaluable support in our work. We sincerely acknowledge the efforts of the University of South Wales and commend them for their commitment to providing life-long learning opportunities and advanced life skills to Healthcare professionals.

| 1. | Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389:1756-1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2199] [Cited by in RCA: 2729] [Article Influence: 303.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, Hendy PA, Smith PJ, Limdi JK, Hayee B, Lomer MCE, Parkes GC, Selinger C, Barrett KJ, Davies RJ, Bennett C, Gittens S, Dunlop MG, Faiz O, Fraser A, Garrick V, Johnston PD, Parkes M, Sanderson J, Terry H; IBD guidelines eDelphi consensus group, Gaya DR, Iqbal TH, Taylor SA, Smith M, Brookes M, Hansen R, Hawthorne AB. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68:s1-s106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1929] [Cited by in RCA: 1726] [Article Influence: 246.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2019] [Cited by in RCA: 1983] [Article Influence: 132.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, Karmiris K, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Kucharzik T, Molnár T, Raine T, Sebastian S, de Sousa HT, Dignass A, Carbonnel F; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 2: Current Management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:769-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1016] [Cited by in RCA: 912] [Article Influence: 101.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Amiot A, Seksik P, Meyer A, Stefanescu C, Wils P, Altwegg R, Vuitton L, Plastaras L, Nicolau A, Pereira B, Duveau N, Laharie D, Mboup B, Boualit M, Allez M, Rajca S, Chanteloup E, Bouguen G, Bazin T, Goutorbe F, Richard N, Moussata D, Vicaut E, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Top-down infliximab plus azathioprine versus azathioprine alone in patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis responsive to intravenous steroids: a parallel, open-label randomised controlled trial, the ACTIVE trial. Gut. 2025;74:197-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Van Assche G, Axler J, Kim HJ, Danese S, Fox I, Milch C, Sankoh S, Wyant T, Xu J, Parikh A; GEMINI 1 Study Group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1576] [Cited by in RCA: 1971] [Article Influence: 151.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, O'Brien CD, Zhang H, Johanns J, Adedokun OJ, Li K, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Van Assche G, Danese S, Targan S, Abreu MT, Hisamatsu T, Szapary P, Marano C; UNIFI Study Group. Ustekinumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 498] [Cited by in RCA: 923] [Article Influence: 131.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, D'Haens GR, Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Danese S, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Niezychowski W, Friedman G, Lawendy N, Yu D, Woodworth D, Mukherjee A, Zhang H, Healey P, Panés J; OCTAVE Induction 1, OCTAVE Induction 2, and OCTAVE Sustain Investigators. Tofacitinib as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-1736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 896] [Cited by in RCA: 1299] [Article Influence: 144.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Le Berre C, Roda G, Nedeljkovic Protic M, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Modern use of 5-aminosalicylic acid compounds for ulcerative colitis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2020;20:363-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Singh S, Proudfoot JA, Dulai PS, Jairath V, Fumery M, Xu R, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ. No Benefit of Concomitant 5-Aminosalicylates in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis Escalated to Biologic Therapy: Pooled Analysis of Individual Participant Data From Clinical Trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1197-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | D'Haens G, Rieder F, Feagan BG, Higgins PDR, Panés J, Maaser C, Rogler G, Löwenberg M, van der Voort R, Pinzani M, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S; International Organization for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Fibrosis Working Group. Challenges in the Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Intestinal Fibrosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:26-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bressler B, Marshall JK, Bernstein CN, Bitton A, Jones J, Leontiadis GI, Panaccione R, Steinhart AH, Tse F, Feagan B; Toronto Ulcerative Colitis Consensus Group. Clinical practice guidelines for the medical management of nonhospitalized ulcerative colitis: the Toronto consensus. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1035-1058.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sands BE. Biomarkers of Inflammation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1275-1285.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Bemelman W, Bryant RV, D'Haens G, Dotan I, Dubinsky M, Feagan B, Fiorino G, Gearry R, Krishnareddy S, Lakatos PL, Loftus EV Jr, Marteau P, Munkholm P, Murdoch TB, Ordás I, Panaccione R, Riddell RH, Ruel J, Rubin DT, Samaan M, Siegel CA, Silverberg MS, Stoker J, Schreiber S, Travis S, Van Assche G, Danese S, Panes J, Bouguen G, O'Donnell S, Pariente B, Winer S, Hanauer S, Colombel JF. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1487] [Cited by in RCA: 1474] [Article Influence: 134.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (116)] |

| 15. | Kornbluth A, Sachar DB; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College Of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:501-23; quiz 524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 899] [Cited by in RCA: 956] [Article Influence: 59.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mak WY, Zhao M, Ng SC, Burisch J. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: East meets west. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:380-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 76.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Glassner KL, Abraham BP, Quigley EMM. The microbiome and inflammatory bowel disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:16-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 631] [Article Influence: 105.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Harbord M, Annese V, Vavricka SR, Allez M, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Boberg KM, Burisch J, De Vos M, De Vries AM, Dick AD, Juillerat P, Karlsen TH, Koutroubakis I, Lakatos PL, Orchard T, Papay P, Raine T, Reinshagen M, Thaci D, Tilg H, Carbonnel F; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation. The First European Evidence-based Consensus on Extra-intestinal Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:239-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 573] [Article Influence: 57.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 19. | Murray A, Nguyen TM, Parker CE, Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8:CD000543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | d'Albasio G, Pacini F, Camarri E, Messori A, Trallori G, Bonanomi AG, Bardazzi G, Milla M, Ferrero S, Biagini M, Quaranta S, Amorosi A. Combined therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid tablets and enemas for maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis: a randomized double-blind study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1143-1147. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Barberio B, Segal JP, Quraishi MN, Black CJ, Savarino EV, Ford AC. Efficacy of Oral, Topical, or Combined Oral and Topical 5-Aminosalicylates, in Ulcerative Colitis: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:1184-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang Y, Parker CE, Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016:CD000544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Murray A, Nguyen TM, Parker CE, Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8:CD000544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Doherty G, Katsanos KH, Burisch J, Allez M, Papamichael K, Stallmach A, Mao R, Berset IP, Gisbert JP, Sebastian S, Kierkus J, Lopetuso L, Szymanska E, Louis E. European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation Topical Review on Treatment Withdrawal ['Exit Strategies'] in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:17-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Herfarth H, Vavricka SR. 5-Aminosalicylic Acid Chemoprevention in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Is It Necessary in the Age of Biologics and Small Molecules? Inflamm Intest Dis. 2022;7:28-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mikami Y, Tsunoda J, Suzuki S, Mizushima I, Kiyohara H, Kanai T. Significance of 5-Aminosalicylic Acid Intolerance in the Clinical Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Digestion. 2023;104:58-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11058] [Cited by in RCA: 16369] [Article Influence: 909.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 28. | Schünemann H, Hill S, Guyatt G, Akl EA, Ahmed F. The GRADE approach and Bradford Hill's criteria for causation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:392-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6581] [Cited by in RCA: 19031] [Article Influence: 2718.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Higgins PD, Rubin DT, Kaulback K, Schoenfield PS, Kane SV. Systematic review: impact of non-adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid products on the frequency and cost of ulcerative colitis flares. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:247-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 31. | Lightner AL. Stem Cell Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019;21:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hawthorne AB, Stenson R, Gillespie D, Swarbrick ET, Dhar A, Kapur KC, Hood K, Probert CS. One-year investigator-blind randomized multicenter trial comparing Asacol 2.4 g once daily with 800 mg three times daily for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1885-1893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Farrell RJ. Biologics beyond Anti-TNF Agents for Ulcerative Colitis - Efficacy, Safety, and Cost? N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1279-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Paoluzi OA, Iacopini F, Pica R, Crispino P, Marcheggiano A, Consolazio A, Rivera M, Paoluzi P. Comparison of two different daily dosages (2.4 vs. 1.2 g) of oral mesalazine in maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis patients: 1-year follow-up study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1111-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Pica R, Cassieri C, Cocco A, Zippi M, Marcheggiano A, De Nitto D, Avallone EV, Crispino P, Occhigrossi G, Paoluzi P. A randomized trial comparing 4.8 vs. 2.4 g/day of oral mesalazine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:933-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Watanabe M, Nishino H, Sameshima Y, Ota A, Nakamura S, Hibi T. Randomised clinical trial: evaluation of the efficacy of mesalazine (mesalamine) suppositories in patients with ulcerative colitis and active rectal inflammation -- a placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:264-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | D'Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Barrett K, Hodgson I, Streck P. Once-daily MMX(®) mesalamine for endoscopic maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1064-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Dignass AU, Bokemeyer B, Adamek H, Mross M, Vinter-Jensen L, Börner N, Silvennoinen J, Tan G, Pool MO, Stijnen T, Dietel P, Klugmann T, Vermeire S, Bhatt A, Veerman H. Mesalamine once daily is more effective than twice daily in patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:762-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kamm MA, Lichtenstein GR, Sandborn WJ, Schreiber S, Lees K, Barrett K, Joseph R. Randomised trial of once- or twice-daily MMX mesalazine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2008;57:893-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kruis W, Kiudelis G, Rácz I, Gorelov IA, Pokrotnieks J, Horynski M, Batovsky M, Kykal J, Boehm S, Greinwald R, Mueller R; International Salofalk OD Study Group. Once daily versus three times daily mesalazine granules in active ulcerative colitis: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Gut. 2009;58:233-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Sandborn WJ, Korzenik J, Lashner B, Leighton JA, Mahadevan U, Marion JF, Safdi M, Sninsky CA, Patel RM, Friedenberg KA, Dunnmon P, Ramsey D, Kane S. Once-daily dosing of delayed-release oral mesalamine (400-mg tablet) is as effective as twice-daily dosing for maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1286-1296, 1296.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kane S, Huo D, Magnanti K. A pilot feasibility study of once daily versus conventional dosing mesalamine for maintenance of ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:170-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kane S, Holderman W, Jacques P, Miodek T. Once daily versus conventional dosing of pH-dependent mesalamine long-term to maintain quiescent ulcerative colitis: Preliminary results from a randomized trial. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2008;2:253-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Mahmud N, O'Toole D, O'Hare N, Freyne PJ, Weir DG, Kelleher D. Evaluation of renal function following treatment with 5-aminosalicylic acid derivatives in patients with ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:207-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Park S, Abdi T, Gentry M, Laine L. Histological Disease Activity as a Predictor of Clinical Relapse Among Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1692-1701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Suzuki Y, Iida M, Ito H, Nishino H, Ohmori T, Arai T, Yokoyama T, Okubo T, Hibi T. 2.4 g Mesalamine (Asacol 400 mg tablet) Once Daily is as Effective as Three Times Daily in Maintenance of Remission in Ulcerative Colitis: A Randomized, Noninferiority, Multi-center Trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:822-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Prantera C, Kohn A, Campieri M, Caprilli R, Cottone M, Pallone F, Savarino V, Sturniolo GC, Vecchi M, Ardia A, Bellinvia S. Clinical trial: ulcerative colitis maintenance treatment with 5-ASA: a 1-year, randomized multicentre study comparing MMX with Asacol. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:908-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Ito H, Iida M, Matsumoto T, Suzuki Y, Sasaki H, Yoshida T, Takano Y, Hibi T. Direct comparison of two different mesalamine formulations for the induction of remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a double-blind, randomized study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1567-1574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Ito H, Iida M, Matsumoto T, Suzuki Y, Aida Y, Yoshida T, Takano Y, Hibi T. Direct comparison of two different mesalamine formulations for the maintenance of remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a double-blind, randomized study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1575-1582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Timmer A, McDonald JW, Macdonald JK. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD000478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Aithal GP, Mansfield JC. Review article: the risk of lymphoma associated with inflammatory bowel disease and immunosuppressive treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1101-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, de Villiers WJ, Present D, Sands BE, Colombel JF. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462-2476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2744] [Cited by in RCA: 2954] [Article Influence: 140.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 53. | Perrier C, Rutgeerts P. Cytokine blockade in inflammatory bowel diseases. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:1341-1352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Panaccione R, Schreiber S, Byczkowski D, Li J, Kent JD, Pollack PF. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn's disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:52-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1598] [Cited by in RCA: 1657] [Article Influence: 87.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Shimizu H, Aonuma Y, Hibiya S, Kawamoto A, Takenaka K, Fujii T, Saito E, Nagahori M, Ohtsuka K, Okamoto R. Long-term efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in patients with ulcerative colitis: 3-year results from a real-world study. Intest Res. 2024;22:369-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Danese S, Vermeire S, Zhou W, Pangan AL, Siffledeen J, Greenbloom S, Hébuterne X, D'Haens G, Nakase H, Panés J, Higgins PDR, Juillerat P, Lindsay JO, Loftus EV Jr, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Chen MH, Sanchez Gonzalez Y, Huang B, Xie W, Liu J, Weinreich MA, Panaccione R. Upadacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from three phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, randomised trials. Lancet. 2022;399:2113-2128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 103.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Hanauer S, Vermeire S, Ghosh S, Liu WJ, Petersen A, Charles L, Huang V, Usiskin K, Wolf DC, D'Haens G. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Ozanimod in Moderately to Severely Active Ulcerative Colitis: Results From the Open-Label Extension of the Randomized, Phase 2 TOUCHSTONE Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:1120-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Dubinsky MC, Panes J, Yarur A, Ritter T, Baert F, Schreiber S, Sloan S, Cataldi F, Shan K, Rabbat CJ, Chiorean M, Wolf DC, Sands BE, D'Haens G, Danese S, Goetsch M, Feagan BG. Etrasimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (ELEVATE): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies. Lancet. 2023;401:1159-1171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 78.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, Zhang H, Strauss R, Johanns J, Adedokun OJ, Guzzo C, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, Gibson PR, Collins J, Järnerot G, Hibi T, Rutgeerts P; PURSUIT-SC Study Group. Subcutaneous golimumab induces clinical response and remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:85-95; quiz e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 563] [Cited by in RCA: 711] [Article Influence: 59.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Reinisch W, Gibson PR, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Strauss R, Johanns J, Padgett L, Adedokun OJ, Colombel JF, Collins J, Rutgeerts P, Tarabar D, Marano C. Long-Term Benefit of Golimumab for Patients with Moderately to Severely Active Ulcerative Colitis: Results from the PURSUIT-Maintenance Extension. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:1053-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Perin RL, Damião AOMC, Flores C, Ludvig JC, Magro DO, Miranda EF, Moraes AC, Nones RB, Teixeira FV, Zeroncio M, Kotze PG. VEDOLIZUMAB IN THE MANAGEMENT OF INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASES: A BRAZILIAN OBSERVATIONAL MULTICENTRIC STUDY. Arq Gastroenterol. 2019;56:312-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV Jr, Danese S, Colombel JF, Törüner M, Jonaitis L, Abhyankar B, Chen J, Rogers R, Lirio RA, Bornstein JD, Schreiber S; VARSITY Study Group. Vedolizumab versus Adalimumab for Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 560] [Cited by in RCA: 545] [Article Influence: 77.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, D'Haens G, Panés J, Kaser A, Ferrante M, Louis E, Franchimont D, Dewit O, Seidler U, Kim KJ, Neurath MF, Schreiber S, Scholl P, Pamulapati C, Lalovic B, Visvanathan S, Padula SJ, Herichova I, Soaita A, Hall DB, Böcher WO. Induction therapy with the selective interleukin-23 inhibitor risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2017;389:1699-1709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 41.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 64. | Parra RS, Chebli JMF, de Azevedo MFC, Chebli LA, Zabot GP, Cassol OS, de Sá Brito Fróes R, Santana GO, Lubini M, Magro DO, Imbrizi M, Moraes ACDS, Teixeira FV, Alves Junior AJT, Gasparetti Junior NLT, da Costa Ferreira S, Queiroz NSF, Kotze PG, Féres O. Effectiveness and Safety of Ustekinumab for Ulcerative Colitis: A Brazilian Multicentric Observational Study. Crohns Colitis 360. 2024;6:otae023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | D'Haens G, Dubinsky M, Kobayashi T, Irving PM, Howaldt S, Pokrotnieks J, Krueger K, Laskowski J, Li X, Lissoos T, Milata J, Morris N, Arora V, Milch C, Sandborn W, Sands BE; LUCENT Study Group. Mirikizumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:2444-2455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 76.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Kierkus J, Higgins PDR, Fischer M, Jairath V, Hirai F, D'Haens G, Belin RM, Miller D, Gomez-Valderas E, Naegeli AN, Tuttle JL, Pollack PF, Sandborn WJ. Efficacy and Safety of Mirikizumab in a Randomized Phase 2 Study of Patients With Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:495-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Ferrante M, D'Haens G, Jairath V, Danese S, Chen M, Ghosh S, Hisamatsu T, Kierkus J, Siegmund B, Bragg SM, Crandall W, Durand F, Hon E, Lin Z, Lopes MU, Morris N, Protic M, Carlier H, Sands BE; VIVID Study Group. Efficacy and safety of mirikizumab in patients with moderately-to-severely active Crohn's disease: a phase 3, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active-controlled, treat-through study. Lancet. 2024;404:2423-2436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Efficacy of Risankizumab Maintenance Therapy by Clinical Remission and Endoscopic Improvement Status in Patients With Moderately to Severely Active Ulcerative Colitis: Post Hoc Analysis of the COMMAND Phase 3 Study. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2024;20:8-9. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Louis E, Schreiber S, Panaccione R, Bossuyt P, Biedermann L, Colombel JF, Parkes G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, D'Haens G, Hisamatsu T, Siegmund B, Wu K, Boland BS, Melmed GY, Armuzzi A, Levine P, Kalabic J, Chen S, Cheng L, Shu L, Duan WR, Pivorunas V, Sanchez Gonzalez Y, D'Cunha R, Neimark E, Wallace K, Atreya R, Ferrante M, Loftus EV Jr; INSPIRE and COMMAND Study Group. Risankizumab for Ulcerative Colitis: Two Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA. 2024;332:881-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Imbrizi M, Magro F, Coy CSR. Pharmacological Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Narrative Review of the Past 90 Years. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16:1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Regueiro M, Siegmund B, Yarur AJ, Steinwurz F, Gecse KB, Goetsch M, Bhattacharjee A, Wu J, Green J, McDonnell A, Crosby C, Lazin K, Branquinho D, Modesto I, Abreu MT. Etrasimod for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis: Analysis of Infection Events from the ELEVATE UC Clinical Programme. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18:1596-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Perin RL, Magro DO, Andrade AR, Argollo M, Carvalho NS, Damião AOMC, Dotti AZ, Ferreira SDC, Flores C, Ludvig JC, Nones RB, Queiroz NSF, Parra RS, Steinwurz F, Teixeira FV, Kotze PG. Effectiveness and Safety of Tofacitinib in the Management of Ulcerative Colitis: A Brazilian Observational Multicentric Study. Crohns Colitis 360. 2023;5:otac050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Parra RS, de Sá Brito Fróes R, Magro DO, da Costa Ferreira S, de Mello MK, de Azevedo MFC, Damião AOMC, de Sousa Carlos A, Barros LL, de Miranda MLQ, Vieira A, Sales MPM, Zabot GP, Cassol OS, Tiburcio Alves AJ Jr, Lubini M, Machado MB, Flores C, Teixeira FV, Coy CSR, Zaltman C, Chebli LA, Sassaki LY, Féres O, Chebli JMF. Tofacitinib for ulcerative colitis in Brazil: a multicenter observational study on effectiveness and safety. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025;25:184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Soldera J. Navigating treatment resistance: Janus kinase inhibitors for ulcerative colitis. World J Clin Cases. 2024;12:5468-5472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Hu T, Wu X, Hu J, Chen Y, Liu H, Zhou C, He X, Zhi M, Wu X, Lan P. Incidence and risk factors for incisional surgical site infection in patients with Crohn's disease undergoing bowel resection. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2018;6:189-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Cassol OS, Zabot GP, Saad-Hossne R, Padoin A. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:4174-4181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 77. | Amadu M, Soldera J. Duodenal Crohn's disease: Case report and systematic review. World J Methodol. 2024;14:88619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Kakkar C, Bonaffini PA, Singh A, Narang V, Mahajan R, Verma S, Singla S, Sood A. MR enterography in Crohns disease and beyond: a pictorial review : Beyond Crohn's: a pictorial guide to MR enterography in small bowel disease. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2025;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Shah Q, Soldera J. Exploring effectiveness of metronidazole, bismuth, and rifaximin in treating small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. World J Methodol. 2026;16(1):107169. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Moghal SS, Soldera J. Comparative Effectiveness of Urine vs. Stool Gluten Immunogenic Peptides Testing for Monitoring Gluten Intake in Coeliac Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life (Basel). 2025;15:1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | El Hage Chehade N, Ghoneim S, Shah S, Pardi DS, Farraye FA, Francis FF, Hashash JG. Efficacy and Safety of Vedolizumab and Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors in the Treatment of Steroid-refractory Microscopic Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2024;58:789-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Jarovsky D, Abreu Almiro MM, Ofenhejm Gotfryd Ben Ezri T, Naaman Berezin E, Almeida FJ, Palazzi Sáfadi MA. Is It Inflammatory Bowel Disease?: A Case of Pediatric Intestinal Paracoccidioidomycosis Resembling Crohn's Disease in an Immunocompetent Infant. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2025;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Mourad FH, Hashash JG, Kariyawasam VC, Leong RW. Ulcerative Colitis and Cytomegalovirus Infection: From A to Z. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:1162-1171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Shah Q, Soldera J. Exploring effectiveness of Metronidazole, Bismuth, and Rifaximin in treating small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. World J Methodol. 2025;In press. |

| 85. | Dagli AJ. Colonic tuberculosis mimicking ulcerative colitis. J Assoc Physicians India. 1999;47:939. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Shojaei E, Walsh JC, Sangle N, Yan B, Silverman MS, Hosseini-Moghaddam SM. Gastrointestinal Histoplasmosis Mimicking Crohn's Disease. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Amoak S, Soldera J. Blastocystis hominis as a cause of chronic diarrhea in low-resource settings: A systematic review. World J Meta-Anal. 2024;12:95631. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Garcia PG, Chebli LA, da Rocha Ribeiro TC, Gaburri PD, de Lima Pace FH, Barbosa KVBD, Costa LA, de Almeida Cruz W, de Assis IC, Moraes BRM, Zanini A, Chebli JMF. Impact of superimposed Clostridium difficile infection in Crohn's or ulcerative colitis flares in the outpatient setting. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:1285-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Visagan R, Grossman R, Dimitriadis PA, Desai A. 'Crohn'z meanz Heinz': foreign body inflammatory mass mimicking Crohn's disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Pellino G, Marcellinaro R, Candilio G, De Fatico GS, Guadagno E, Campione S, Santangelo G, Reginelli A, Sciaudone G, Riegler G, Canonico S, Selvaggi F. The experience of a referral centre and literature overview of GIST and carcinoid tumours in inflammatory bowel diseases. Int J Surg. 2016;28 Suppl 1:S133-S141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Jarrett P, Duffill M, Oakley A, Smith A. Pellagra, azathioprine and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:44-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Lai T, Frugoli A, Barrows B, Salehpour M. Sevelamer Carbonate Crystal-Induced Colitis. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2020;2020:4646732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Del Val A, García Campos M, García Morales N. Sprue-like enterophaty asscociated with valsartan. Med Clin (Barc). 2018;150:329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Aver GP, Ribeiro GF, Ballotin VR, Santos FSD, Bigarella LG, Riva F, Brambilla E, Soldera J. Comprehensive analysis of sodium polystyrene sulfonate-induced colitis: A systematic review. World J Meta-Anal. 2023;11:351-367. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Ballotin VR, Bigarella LG, Riva F, Onzi G, Balbinot RA, Balbinot SS, Soldera J. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome associated with inflammatory bowel disease: A case report and systematic review. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:4075-4093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Brambilla B, Barbosa AM, Scholze CDS, Riva F, Freitas L, Balbinot RA, Balbinot S, Soldera J. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Case Report and Systematic Review. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2020;5:49-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/