Published online Feb 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i6.1416

Peer-review started: October 9, 2020

First decision: December 3, 2020

Revised: December 15, 2020

Accepted: December 22, 2020

Article in press: December 22, 2020

Published online: February 26, 2021

Processing time: 119 Days and 7.7 Hours

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), or sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a benign histiocytic disorder. Extranodal involvement is common, occurring in > 40% of patients, but bone involvement occurs in < 10% of cases. In addition, primary bone RDD is extremely rare. The majority of patients are adolescents and young adults, and the mean age at onset is 20-years-old.

We report an 8-year-old Chinese girl who presented to our hospital with an insidious onset of swelling and pain in the middle shaft of her right tibia for 4 mo. We performed total surgical resection of the right tibia lesion and allograft transplantation. A good prognosis was confirmed at the 6 mo follow-up. Pain and swelling symptoms were totally relieved, range of motion of her right knee and ankle returned to normal, and there was no clinical evidence of lesion recurrence at last follow up. Our case is the second reported case of osseous RDD without lymphadenopathy in the shaft of the tibia of a child.

Extranodal RDD is a rare disease and can be misdiagnosed easily. Lesion resection and allograft transplantation are an option to treat extranodal RDD in children with good short term result. Pediatric orthopedist should be aware of this rare disease, especially extranodal involvement.

Core Tip: Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD) is a rare disease and can be misdiagnosed easily. We report an 8-year-old Chinese female case. We performed total surgical resection of the right tibia lesion and allograft transplantation. A good prognosis was confirmed at the 6 mo follow-up. Pain and swelling symptoms were totally relieved, movement range of right knee and ankle return to normal, and there was no clinical evidence of lesion recurrence at last follow up. Our case is the second reported case of osseous RDD without lymphadenopathy in the shaft of tibia of a child.

- Citation: Vithran DTA, Wang JZ, Xiang F, Wen J, Xiao S, Tang WZ, Chen Q. Osseous Rosai-Dorfman disease of tibia in children: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(6): 1416-1423

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i6/1416.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i6.1416

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD) was first described in the literature by Destombes in 1965[1] and was recognized by Rosai and Dorfman as a distinct clinicalopathological entity in 1969[2]. The etiology of this disease remains uncertain, with theories based on a histiocytic reaction caused by cytokines or an unexplained infection[3]. Traditionally, it belongs to non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis, which refers to uncommon conditions characterized by accumulation and overproduction of macrophage-dendritic lineage cells. A recent update of this classification suggested that the symptoms of RDD are sufficiently special for it to warrant one group of its own in histiocytosis disorders[4].

Large, painless cervical lymphadenopathy is the most common clinical presentation of this condition, mainly in kids, adolescents, or young adults[2]. Extranodal involvement is widespread, from which nearly 40% of patients suffer, and is very common in the elderly. The skin, upper respiratory tract, orbits, central nervous system, and sometimes the gastrointestinal tract are the most common sites of extranodal involvement[5]. In less than 10% of patients, bone is the secondary site of RDD[6]. Osseous involvement without lymphadenopathy (primary bone disease) is rarer, and there are few reported cases[7]. There are different symptoms and physical findings in RDD depending on the different areas of the body that are affected.

The etiology of RDD is unclear, and diagnosis involves thorough pathological examination of the tissue involved. No matter which area is involved, most cases have spontaneously relieved months to years after diagnosis. We report another case of extranodal RDD with a solitary bone lesion, and our case is the second reported case of osseous RDD without lymphadenopathy in the right tibial shaft of a child.

An 8-year-old girl presented with swelling and pain in the right leg for 4 mo without lymphadenopathy.

She initially presented with the same symptoms in the right leg at a local hospital for treatment, and X-ray showed a lesion in the middle shaft of the right tibia. The patient was admitted to our hospital after a 3 mo delay. There has been no history of sweating at night, diminished appetite, or weight loss.

The patients presented with low-grade fever, swelling, and obvious pain in the middle side of the right tibia. There was limited movement of the adjacent joints and normal blood supply of the extremities, with normal neurological sensation of the tibia. There was no cervical, axillary, popliteal, or inguinal lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory examination data were within normal ranges, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, rheumatoid factor, tumor markers, and urinary routine test.

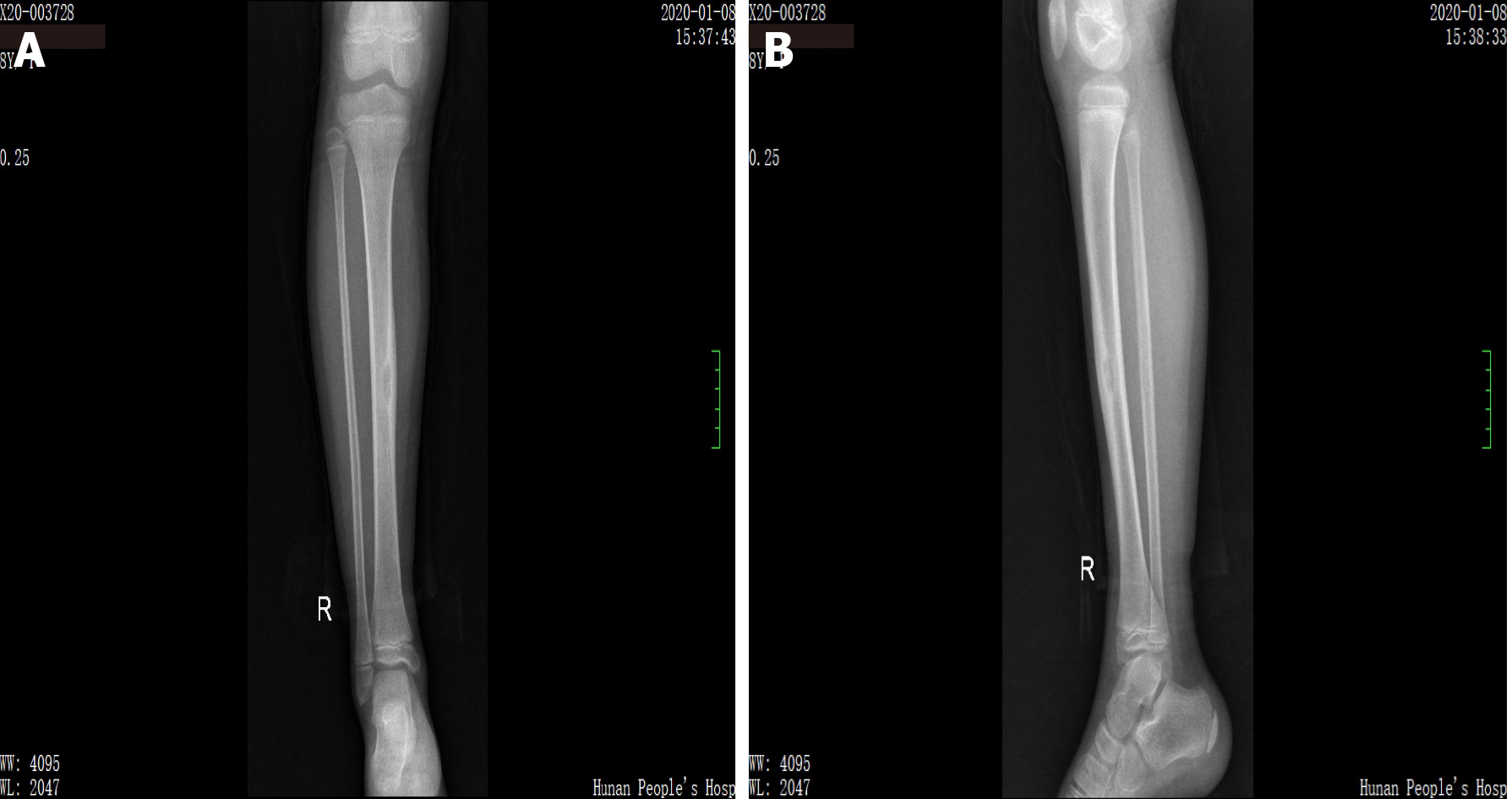

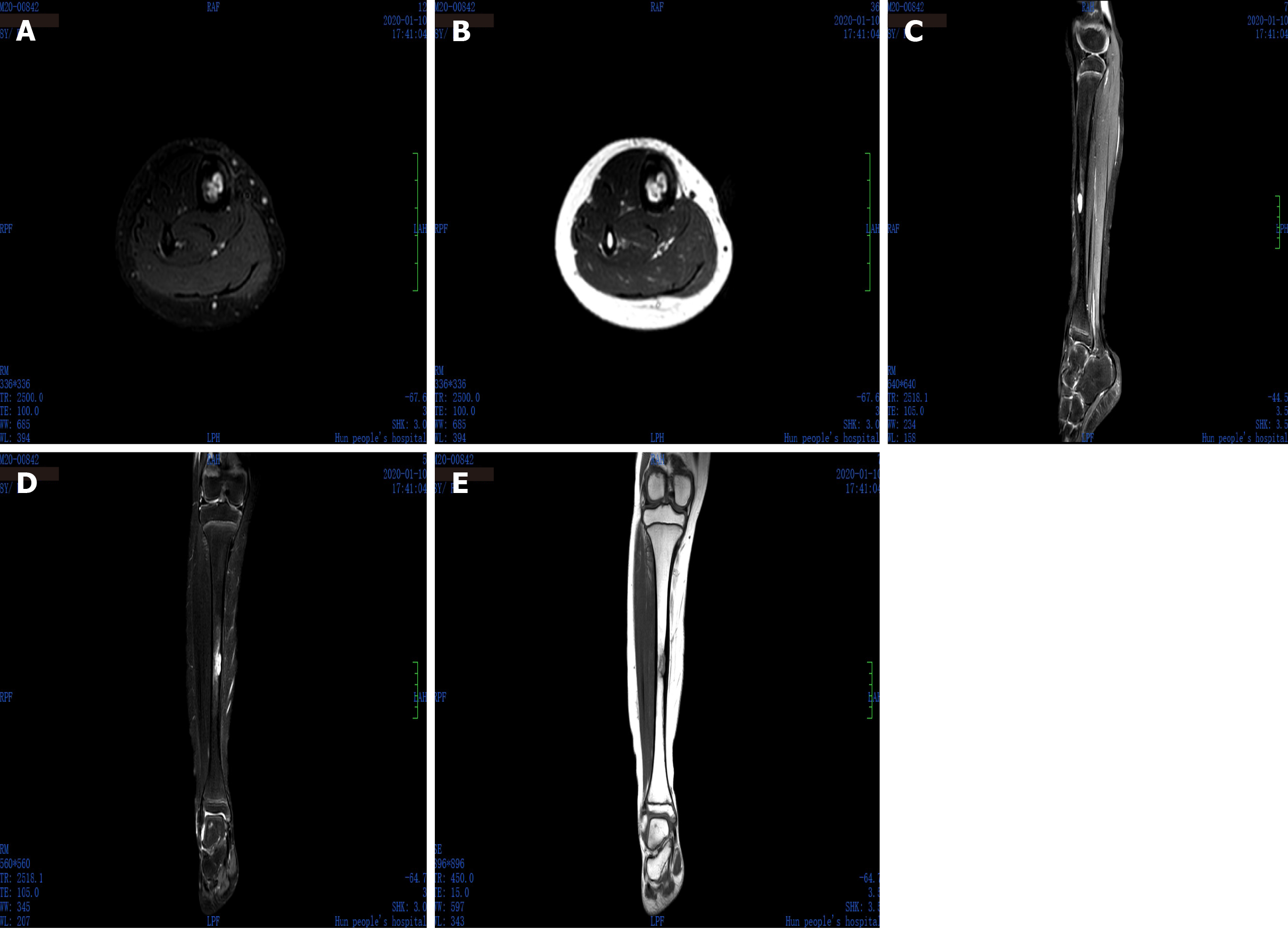

X-ray showed right tibial lesion (Figure 1). Computed tomography revealed a similar round cystic bone defect area with sclerotic margins, the range was about 10 mm × 9 mm × 18 mm, the adjacent bone cortex was obviously thickened, periosteal reaction was visible, and no definite swelling was found in the surrounding soft tissue (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance images shows a well-defined intra-osseous lesion extending close to the posterior tibial cortex (Figure 3).

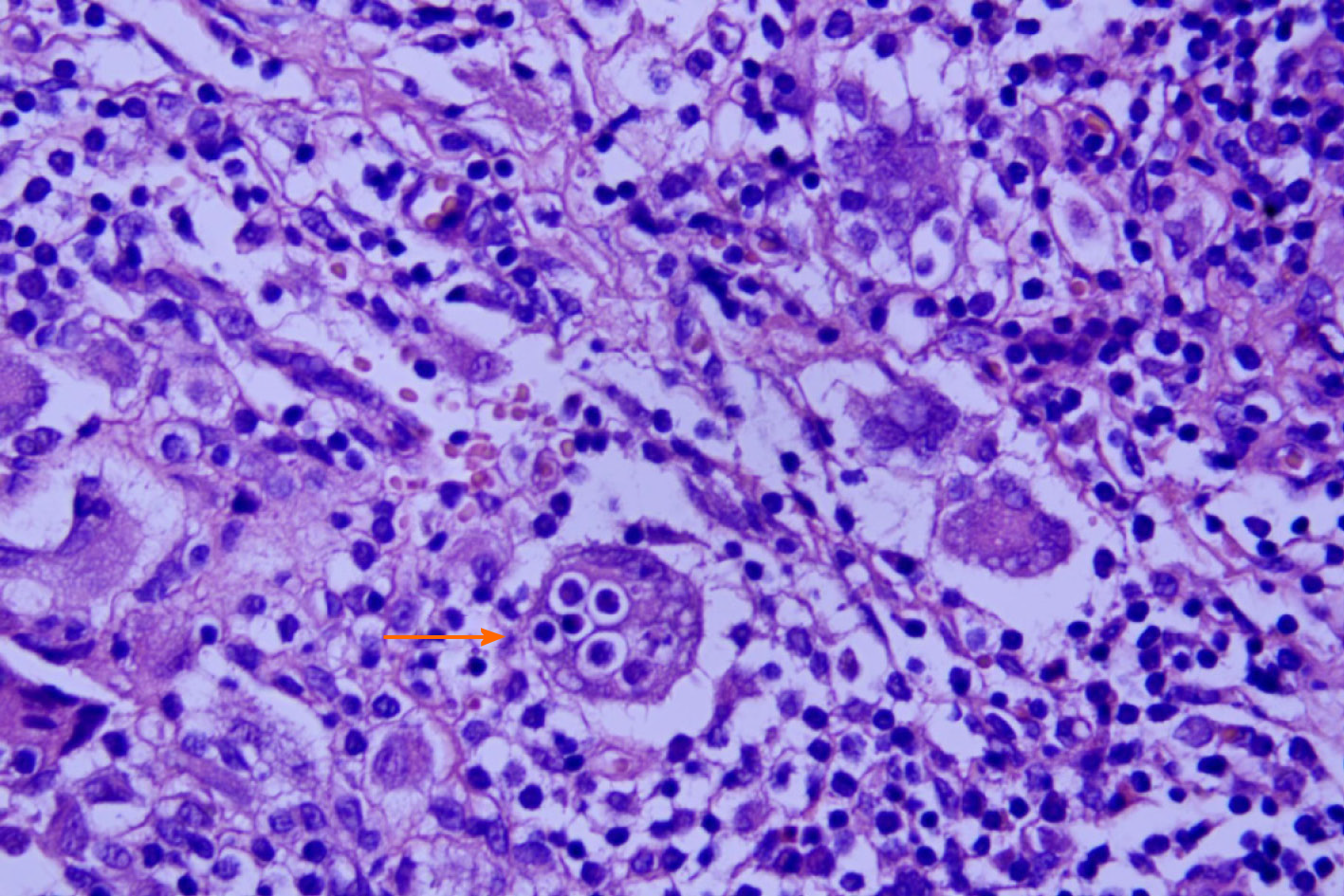

The results of the biopsy confirm osseous RDD (Figure 4); immunohistochemistry result: CD207 (+), S-100 (+), CD1a (-), CD68 (+), CD163 (+), Ki67 (inflammatory cell +), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (-), CD30 (-), CD5 (+), and CD20 (+); special staining: Hexamine silver (-).

The patient received an open biopsy and curettage of the lesion under general anesthesia via a longitudinal anterior approach of the right middle tibia. The medial cortex of the tibia was removed by osteotome for 3 cm × 1 cm. The lesion tissue in the cavity was curetted for a biopsy. After the cavity was thoroughly irrigated, allograft bone was filled into it. Sufficient allograft bone transplant was confirmed by fluoroscopy. After the operation, the patient was given a cast for 6 wk.

Knee pain and swelling were relieved significantly after surgery. At the 6 mo follow-up, there was no clinical evidence of lesion recurrence; radiology test showed that the lesion had disappeared. Allograft induced osteogenesis, and the function of the right tibia was fully recovered.

More than 1282 cases have been reported with this rare condition, but only 12 cases of primary intra-osseous tibia RDD have been identified in English literature (Table 1). There has been previously only one case of intra-osseous RDD of the tibia without lymphadenopathy in a young patient[8]. RDD is much more commonly seen in males, African-Americans, and in infancy or young adult[5], and the average age of onset is 20 years. Foucar, Rosai, and Dorfman published the largest RDD analysis in 1990 and included 423 cases with a histopathological diagnosis of RDD[9]. The incidence of RDD along with primary bone involvement is rare at 2%-8%[10].

| Ref. | Year | Case | Age | Site | Classification |

| Patterson et al[26] | 1997 | 1 | 17 | Tibia | Extranodal |

| Goel et al[8] | 2003 | 1 | 7 | Shaft of tibia | Extranodal |

| Mota Gamboa et al[27] | 2004 | 1 | 19 | Tibia | Extranodal |

| Demicco et al[18] | 2010 | 6 | 11-22 | Proximal tibia | Extranodal/nodal |

| Orvets et al[21] | 2013 | 1 | 56 | Tibia | Extranodal |

| Mannelli et al[28] | 2015 | 1 | 49 | Left proximal tibia | Extranodal |

| Xu et al[29] | 2015 | 1 | 56 | Right proximal tibia | Extranodal |

Although it is an idiopathic disorder, the occurrence of RDD frequently arises following infectious disease. Therefore, some authors suggested potential viral etiologies, including Epstein-Barr virus, human herpes virus 6, parvovirus B19, and polyomavirus Klebsiella, according to immunohistochemistry, polymerase chain reaction, and in situ hybridization studies[4,5]. Without the immunohistochemistry and molecular findings obtained in these studies, the relationship between both the virus and RDD etiology stays unclear[4].

In general, the onset of RDD is subtle, with an average interval of 3-6 mo between the appearance of signs and symptoms and diagnosis. Nonspecific systemic symptoms as fever, malaise, weight loss, and nighttime sweating can be present. The clinical image in the case of extranodal localizations depend on the organ or apparatus affected. The only systemic symptom of the patient was low-grade fever and swelling of the tibia.

Multiple large histiocytes containing abundant eosinophilic cytoplasms, including a variable cellular, combined inflammatory infiltrate composed of plasma cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, foamy macrophages, and unusual eosinophils, are distinguished as the pathological findings of RDD in the present case. The significant characteristic of major histiocytes in RDD is prominent emperipolesis, namely lymphocytophagocytosis, with intracellular lymphocytes, plasma cells, or neutrophils[11].

The differential diagnosis of extranodal RDD of the bone is occasionally difficult because of the occurrence of clinical signs and symptoms that are nonspecific and because of lesion rarity and the less classic radiologic features observed at times[12]. Skeletal pain is common, but pathological fractures are rare[13]. Bone lesions usually occur in metaphysis or diaphysis, are osteolytic or combined lytic/sclerotic, and have a slender transition zone, and soft tissue expansion can occur. Medical differential diagnosis of pediatric bone tumors involves chronic osteomyelitis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, fibrous dysplasia, lymphoma, and Ewing sarcoma. Femur and tibia lesions should raise questions about Erdheim-Chester disease. The prognosis of bone RDD is usually good[14]. Immunohistochemistry staining for S-100 and CD68 is helpful in separating RDD from the above described diseases[15]. In the current case, the microscopic results showed emperipolesis inside the cytoplasm of histiocytes. Immunohistochemistry was CD207 (+), S-100 (+), CD1a (-), CD68 (+), CD163 (+), Ki67 (inflammatory +), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (-), CD30 (-), CD5 (+), CD20 (+).

According to World Health Organization classification of tumors, these lesions are categorized as a reactive condition of unknown etiology[4]. In 2016, histiocytoses have been differentiated into five types: C, H, L, M, and R. Type R included RDD, non-Langerhans histiocytosis cells, and miscellaneous non-cutaneous. RDD itself has been divided into subtypes associated with neoplasia-associated, classical (nodal), extranodal, familial, and immune disease[16].

Extranodal RDD accompanied by lymphadenopathy is seen in almost half of the cases; however, extranodal manifestation of RDD in the absence of lymphadenopathy is extremely rare in adolescents[17]. The skin, respiratory tract, orbital cavity, and the central nervous system are the main extranodal sites involved, followed by skeleton solitary bone involvement in the absence of lymphadenopathy that has been noted in extremely few cases. Primary RDD of bone is usually solitary and was described in the skull, tibia, clavicle, sacrum, femur, and bones of the hands and feet[18,19]. In recent studies, cranium (31%), facial bones (22%), and tibia (18%) were most commonly affected, followed by the spine/sacrum, femur, and pelvis. In addition, the primary bone disease mostly occurred in adulthood and usually affected only one or two bones[7]. We have diagnosed this patient with a primary osseous RDD without lymphadenopathy or other extranodal findings, and biopsy confirmed the diagnosis. The presence of macrophages, known as Rosai-Dorfman cell histologic findings, confirm because of the aspects that are mixed together with lymphocytes, plasma cell infiltration of the lymph nodes, which is the same as mentioned in other articles[16].

For many patients, spontaneous recovery of RDD occurs within months or years. Clinical non-treatment observation should be considered as the first choice no matter what. The natural history of RDD remain controversial; but it is accepted by most authors to have a benign, proliferative, and self-limiting mechanism with an excellent prognosis[9,20]. There is no accepted treatment protocol for primary RDD of bone in children and young adults. Generally, patients of RDD often do not need treatment and can recover spontaneously in nearly 80% cases[21,22]. However, the existence of vital organ involvement and secondary involvement of bone, which has been reported as a marker of increased risk of death, may indicate high mortality[9], specifically in extreme extranodal forms in children with central nervous system, renal, or respiratory tract involvement[23]. In cases of systemic implication, therapeutic options comprise possible surgical resection, corticosteroids, rituximab, and diverse chemotherapeutic agents[5,24]. Primary RDD of bone is believed not to increase mortality risk, so the treatment may relieve the pain or prevent complications, especially in children that can have growth disturbance due to a pathological fracture.

The most frequent therapy mentioned in these instance include surgical lesion resection, curettage, and bone grafting[18]. The post-operative relapse is very uncommon and can be caused by incomplete debulking and multiple organ implication[25]. In our case, the patient underwent surgical resection of the lesion and allograft transplantation; after 6 mo follow-up, the allograft induced osteogenesis and the patient was able to use her right tibia with full function.

RDD is a rare disorder that is not only nodal but also extranodal. Extranodal involvement in RDD is uncommon, and bone involvement occurs in less than 10% of cases. This rare disease should be known by all pediatric orthopedists and should be regarded as a differential diagnosis when osteolytic lesions, particularly extranodal implications, occur in children. In order to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of these surgical procedures for children with RDD of the tibia, further research is required.

| 1. | Destombes P. [Adenitis with lipid excess, in children or young adults, seen in the Antilles and in Mali. (4 cases)]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1965;58:1169-1175. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. A newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Chan JK, Tsang WY. Uncommon syndromes of reactive lymphadenopathy. Semin Oncol. 1993;20:648-657. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Fu X, Jiang JH, Tian XY, Li Z. Isolated spinal Rosai-Dorfman disease misdiagnosed as lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma by intraoperative histological examination. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2015;32:72-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dalia S, Sagatys E, Sokol L, Kubal T. Rosai-Dorfman disease: tumor biology, clinical features, pathology, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2014;21:322-327. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Mehraein Y, Wagner M, Remberger K, Füzesi L, Middel P, Kaptur S, Schmitt K, Meese E. Parvovirus B19 detected in Rosai-Dorfman disease in nodal and extranodal manifestations. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:1320-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mosheimer BA, Oppl B, Zandieh S, Fillitz M, Keil F, Klaushofer K, Weiss G, Zwerina J. Bone Involvement in Rosai-Dorfman Disease (RDD): a Case Report and Systematic Literature Review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Goel MM, Agarwal PK, Agarwal S. Primary Rosai-Dorfman disease of bone without lymphadenopathy diagnosed by fine needle aspiration cytology. A case report. Acta Cytol. 2003;47:1119-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Duijsens HM, Vanhoenacker FM, ter Braak BP, Hogendoorn PC, Kroon HM. Primary intraosseous manifestation of Rosai-Dorfman disease: 2 cases and review of literature. JBR-BTR. 2014;97:84-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46:95-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 505] [Cited by in RCA: 692] [Article Influence: 57.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schein C, Kluskens L, Gattuso P. Fine-needle aspiration of primary Rosai-Dorfman disease of the bone without peripheral lymphadenopathy: a challenging diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:230-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sasaki K, Pemmaraju N, Westin JR, Wang WL, Khoury JD, Podoloff DA, Moon B, Daver N, Borthakur G. A single case of rosai-dorfman disease marked by pathologic fractures, kidney failure, and liver cirrhosis treated with single-agent cladribine. Front Oncol. 2014;4:297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Paryani NN, Daugherty LC, O'Connor MI, Jiang L. Extranodal rosai-dorfman disease of the bone treated with surgery and radiotherapy. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:5531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shi SS, Sun YT, Guo L. Rosai-Dorfman disease of lung: a case report and review of the literatures. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009;122:873-874. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, Horne A, Haroche J, Donadieu J, Requena-Caballero L, Jordan MB, Abdel-Wahab O, Allen CE, Charlotte F, Diamond EL, Egeler RM, Fischer A, Herrera JG, Henter JI, Janku F, Merad M, Picarsic J, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Rollins BJ, Tazi A, Vassallo R, Weiss LM; Histiocyte Society. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in RCA: 1047] [Article Influence: 104.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Shulman S, Katzenstein H, Abramowsky C, Broecker J, Wulkan M, Shehata B. Unusual presentation of Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD) in the bone in adolescents. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2011;30:442-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Demicco EG, Rosenberg AE, Björnsson J, Rybak LD, Unni KK, Nielsen GP. Primary Rosai-Dorfman disease of bone: a clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1324-1333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Baker JC, Kyriakos M, McDonald DJ, Rubin DA. Primary Rosai-Dorfman disease of the femur. Skeletal Radiol. 2017;46:129-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lima FB, Barcelos PS, Constâncio AP, Nogueira CD, Melo-Filho AA. Rosai-Dorfman disease with spontaneous resolution: case report of a child. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2011;33:312-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Orvets ND, Mayerson JL, Wakely PE Jr. Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease as solitary lesion of the tibia in a 56-year-old woman. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2013;42:420-422. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Pulsoni A, Anghel G, Falcucci P, Matera R, Pescarmona E, Ribersani M, Villivà N, Mandelli F. Treatment of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): report of a case and literature review. Am J Hematol. 2002;69:67-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Warrier R, Chauhan A, Jewan Y, Bansal S, Craver R. Rosai-Dorfman disease with central nervous system involvement. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2012;10:196-198. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Abla O, Jacobsen E, Picarsic J, Krenova Z, Jaffe R, Emile JF, Durham BH, Braier J, Charlotte F, Donadieu J, Cohen-Aubart F, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Allen C, Whitlock JA, Weitzman S, McClain KL, Haroche J, Diamond EL. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and clinical management of Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease. Blood. 2018;131:2877-2890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 51.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Huang BY, Zong M, Zong WJ, Sun YH, Zhang H, Zhang HB. Intracranial Rosai-Dorfman disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;32:133-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Patterson FR, Rooney MT, Damron TA, Vermont AI, Hutchison RE. Sclerotic lesion of the tibia without involvement of lymph nodes. Report of an unusual case of Rosai-Dorfman disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:911-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mota Gamboa JD, Caleiras E, Rosas-Uribe A. Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease. Clinical and pathological characteristics in a patient with a pseudotumor of bone. Pathol Res Pract. 2004;200:423-6; discussion 427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mannelli L, Monti S, Love JE, Kussick SJ, McLuen A, Behnia F. Primary Rosai-Dorfman disease of the bone in a patient with history of breast cancer: appearance on 99mTc-MDP scintigraphy, CT, and X-ray. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:247-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Xu J, Liu CH, Wang YS, Chen CX. Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman Disease as Isolated Lesion of the Tibia Diagnosed by Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology: A Case Report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nussler AK S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH