Published online Feb 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i4.970

Peer-review started: November 10, 2020

First decision: November 29, 2020

Revised: December 3, 2020

Accepted: December 11, 2020

Article in press: December 11, 2020

Published online: February 6, 2021

Processing time: 75 Days and 23.9 Hours

Aortic dissection (AD) is an emergent and life-threatening disorder, and its in-hospital mortality was reported to be as high as 24.4%-27.4%. AD can mimic other more common disorders, especially acute myocardial infarction (AMI), in terms of both symptoms and electrocardiogram changes. Reperfusion for patients with AD may result in catastrophic outcomes. Increased awareness of AD can be helpful for early diagnosis, especially among younger patients.

We report a 28-year-old man with acute left side chest pain without cardiovascular risk factors. He was diagnosed with acute inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), which, based on illness history, physical examination, and intraoperative findings, was eventually determined to be type A AD caused by Marfan syndrome. Emergent coronary angiography revealed the anomalous origin of the right coronary artery as well as eccentric stenosis of the proximal segment. Subsequently, computed tomography angiography (CTA) showed intramural thrombosis of the ascending aorta. Finally, the patient was transferred to the cardiovascular surgery department for a Bentall operation. He was discharged 13 d after the operation, and aortic CTA proved a full recovery at the 2-year follow-up.

It is essential and challenging to differentiate AD from AMI. Type A AD should be the primary consideration in younger STEMI patients without cardiovascular risk factors but with outstanding features of Marfan syndrome.

Core Tip: We report a 28-year-old man who presented with acute chest pain and was diagnosed with acute inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction that was later found to be aortic dissection (AD) induced by Marfan syndrome. Differentiating AD from acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remains difficult. Suspicion of Marfan syndrome in young patients without risk factors for atherosclerosis increases the likelihood of AD over AMI. Difficulty in engaging the coronary artery or the presence of proximal eccentric stenosis is suggestive of type A AD.

- Citation: Zhang YX, Yang H, Wang GS. Acute inferior wall myocardial infarction induced by aortic dissection in a young adult with Marfan syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(4): 970-975

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i4/970.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i4.970

Aortic dissection (AD) is one of the leading cardiovascular causes of death, with an incidence of 4.3/100000-4.4/100000 per year[1,2]; Marfan syndrome accounted for 1.5% of all cases[1]. AD has variable manifestations, of which acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is rare, especially among younger patients. However, misdiagnosis of AD as AMI and subsequent thrombolysis can be a catastrophe. It is essential and challenging to differentiate AD from AMI. We present a 28-year-old man with acute inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) that was later found to have type A AD caused by Marfan syndrome.

A 28-year-old man presented to our emergency department with acute left side chest pain accompanied by palpitation and sweating.

The patient’s symptoms started 60 min ago.

The patient had no relevant past history.

No significant personal or family history was identified.

Vital signs showed a blood pressure of 170/132 mmHg and heart rate of 70 beats per minute.

The laboratory results showed a serum troponin T level of 0.01 ng/mL and a D-dimer level of 0.10 µg/mL.

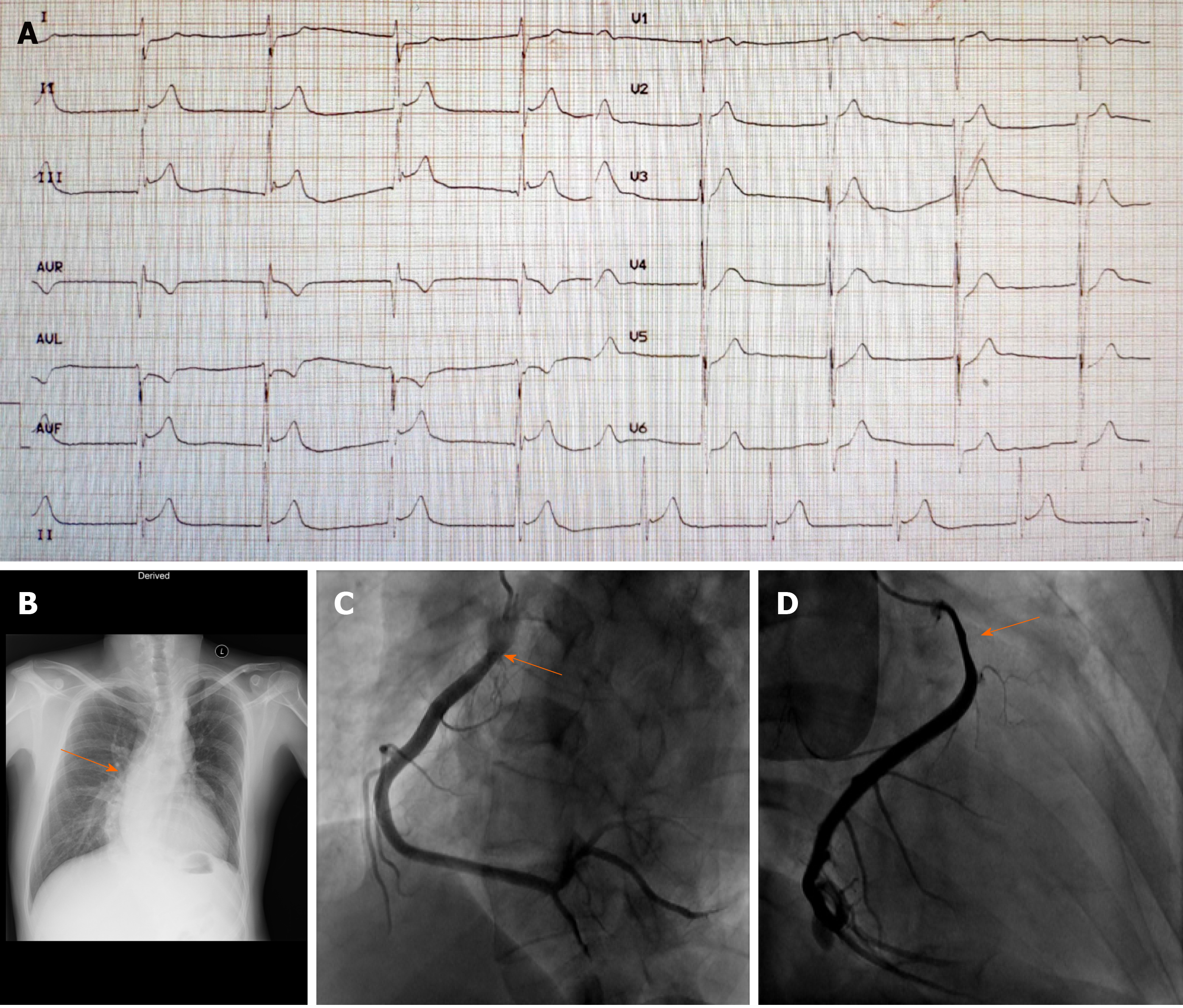

Twelve lead electrocardiograms (ECGs) showed ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF and deep reciprocal ST depression in leads I and aVL (Figure 1A). Chest X-rays showed scoliosis (Figure 1B). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed mild inferior wall hypokinesia and moderate aortic regurgitation.

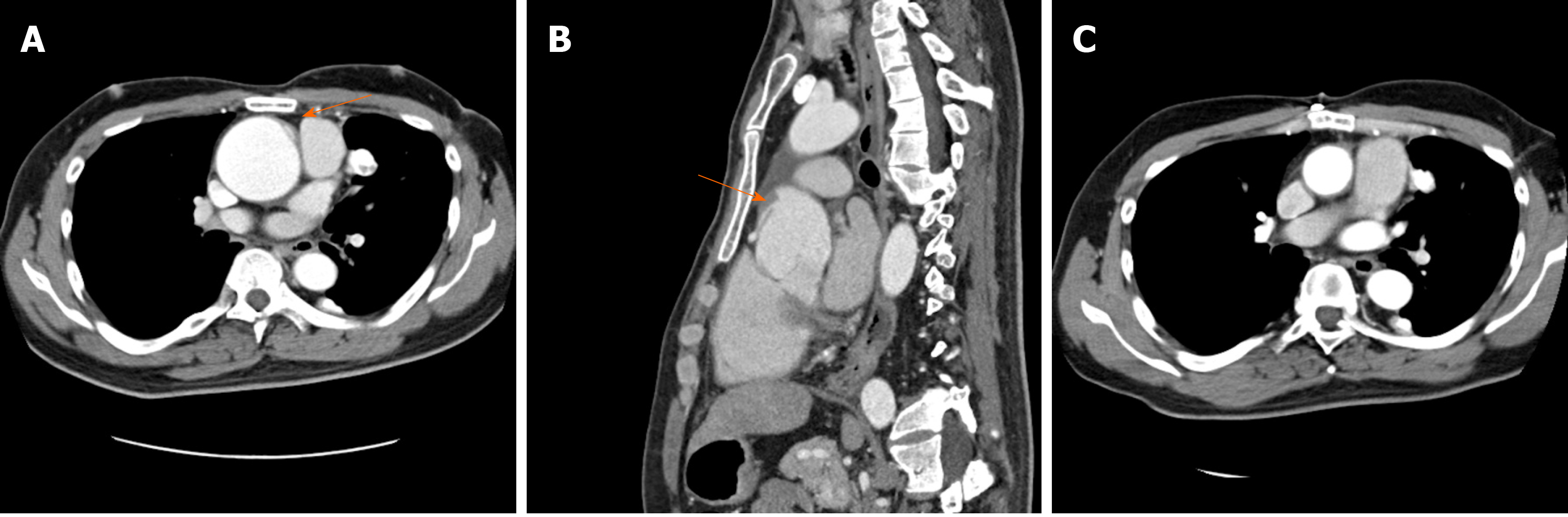

Under the impression of STEMI, the patient was sent promptly for emergent coronary angiography. The initial attempt to engage the right coronary ostium failed. Finally, right coronary angiography was performed using a multipurpose catheter, and it revealed the anomalous origin of the right coronary artery (RCA) as well as eccentric stenosis of the proximal segment where neither a thrombus nor dissection flap was seen (Figure 1C and D). Subsequent computed tomography angiography (CTA) revealed irregularities in the ascending aortic intima with a concomitant linear low-density shadow, which was highly suspected of thrombosis from type A AD. (Figure 2A and B).

The RCA originated from the junction of the left and right coronary sinus above the ostium of the left coronary artery. An extended aneurysm of the ascending aortic root (58 mm in diameter) and avulsion of the aortic wall accompanied by localized intramural thrombosis close to the ostium of the RCA were observed with direct visualization during the operation.

With a history of pneumothorax, diastolic murmur in the aortic area, thumb sign, wrist sign, pectus excavatum, scoliosis, and myopia 4 diopter, the patient was diagnosed with Marfan syndrome.

The patient underwent a Bentall operation with replacement of the ascending aorta and the aortic valve.

The patient fully recovered and was discharged 13 d after the operation. The aortic CTA proved a full recovery at the 2-year follow-up (Figure 2C).

In this case, STEMI was associated with an unusual etiology, type A AD, which was induced by Marfan syndrome. AD is one of the leading cardiovascular causes of death, with an incidence of 4.3/100000-4.4/100000 per year[1,2] and in-hospital mortality of 24.4%-27.4%[3,4]. The presentations of AD can mimic AMI in terms of both symptoms and ECG findings. Additionally, coronary involvement is present in 10%-15% of patients with AD[5]. The proposed mechanisms of AMI due to AD were: (1) Compression by a false lumen or hematoma; (2) Ostium obstruction by an intimal flap; (3) Coronary artery dissection; (4) Coronary artery spasm; or (5) Avulsion[6]. Reperfusion therapy along with misdiagnosis, especially thrombolysis, may lead to catastrophic outcomes[7,8]. Therefore, it is essential to identify AMI that was induced by type A AD and not coronary thrombosis-associated plaque rupture[9,10].

For the 28-year-old man, the few risk factors for atherosclerosis, accompanied by physical signs of Marfan syndrome, provided clues to suggest AD over AMI. The Framingham Heart Study[11] suggested that the 10-year incidence of MI was as high as 51.1/1000 in young male patients, making it more challenging to differentiate AD from AMI in the first place. However, the individuals with increased MI risk had a higher prevalence of smoking and family history of premature CHD and hyperlipidemia[6,12]. For this patient, who lacked cardiovascular risk factors, the AD risk score was reviewed as 2 (high risk) based on high-risk predisposing conditions and examination features[13]. In the IRAD study[14], AD patients younger than 40 years of age were less likely to have a prior history of hypertension (34% vs 72%) or atherosclerosis (1% vs 30%) but more likely to have Marfan syndrome (50% vs 2%) than those who were older. In summary, it is essential to be aware of AD in patients at low risk for atherosclerosis who present with suspected AMI, especially in younger adults.

The outstanding feature of this patient on TTE was the extended ascending aorta dimensions and moderate aortic regurgitation. The typical feature of AD on TTE is an intimal flap separating two lumina. Aortic regurgitation and pericardial effusion are also present in AD[5]. Aortic regurgitation occurred in 40%-76% of cases of type A AD. Possible mechanisms are dilation of the aortic annulus secondary to dilation of the ascending aorta[15]. Naturally, the absence of an intimal flap on TTE alone is less reliable for ruling out AD.

In this case, we found it initially difficult to engage the right coronary ostium and finally revealed eccentric stenosis of the proximal segment of the RCA with an anomalous origin. In a study by Wang et al[16], increased resistance while advancing the diagnostic catheter was felt in 60% of cases with STEMI secondary to AD. To a large extent, ostium involvement of the left or RCA is also suggestive of aortic root dissection. In addition, Huang et al[17] found a marked pressure difference between the radial artery and the ascending aorta, suggesting AD. We propose that difficulty in engaging coronary ostium or detection of proximal eccentric stenosis of the coronary artery could be suggestive of type A AD.

Generally, it is challenging to differentiate AD from AMI. In the emergency department, AD should be the principal differential diagnosis in patients with chest pain, especially in those with few risk factors for atherosclerosis. Suspicion of Marfan syndrome increases the possibility of AD over AMI. Difficulty in engaging the coronary artery or the presence of proximal eccentric stenosis raises suspicion of type A AD.

| 1. | Yu HY, Chen YS, Huang SC, Wang SS, Lin FY. Late outcome of patients with aortic dissection: study of a national database. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25:683-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | DeMartino RR, Sen I, Huang Y, Bower TC, Oderich GS, Pochettino A, Greason K, Kalra M, Johnstone J, Shuja F, Harmsen WS, Macedo T, Mandrekar J, Chamberlain AM, Weiss S, Goodney PP, Roger V. Population-Based Assessment of the Incidence of Aortic Dissection, Intramural Hematoma, and Penetrating Ulcer, and Its Associated Mortality From 1995 to 2015. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:e004689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pape LA, Awais M, Woznicki EM, Suzuki T, Trimarchi S, Evangelista A, Myrmel T, Larsen M, Harris KM, Greason K, Di Eusanio M, Bossone E, Montgomery DG, Eagle KA, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, O'Gara P. Presentation, Diagnosis, and Outcomes of Acute Aortic Dissection: 17-Year Trends From the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:350-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 827] [Article Influence: 75.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, Bruckman D, Karavite DJ, Russman PL, Evangelista A, Fattori R, Suzuki T, Oh JK, Moore AG, Malouf JF, Pape LA, Gaca C, Sechtem U, Lenferink S, Deutsch HJ, Diedrichs H, Marcos y Robles J, Llovet A, Gilon D, Das SK, Armstrong WF, Deeb GM, Eagle KA. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA. 2000;283:897-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2417] [Cited by in RCA: 2393] [Article Influence: 92.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, Bossone E, Bartolomeo RD, Eggebrecht H, Evangelista A, Falk V, Frank H, Gaemperli O, Grabenwöger M, Haverich A, Iung B, Manolis AJ, Meijboom F, Nienaber CA, Roffi M, Rousseau H, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Allmen RS, Vrints CJ; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: Document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2873-2926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2374] [Cited by in RCA: 3212] [Article Influence: 267.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Goran KP. Suggestion to list acute aortic dissection as a possible cause of type 2 myocardial infarction (according to the universal definition). Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2819-2820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tsigkas G, Kasimis G, Theodoropoulos K, Chouchoulis K, Baikoussis NG, Apostolakis E, Bousoula E, Moulias A, Alexopoulos D. A successfully thrombolysed acute inferior myocardial infarction due to type A aortic dissection with lethal consequences: the importance of early cardiac echocardiography. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Koracevic GP. Prehospital thrombolysis expansion may raise the rate of its inappropriate administration in ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction induced by aortic dissection. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:628-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, White HD; Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Circulation. 2018;138:e618-e651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1019] [Cited by in RCA: 2414] [Article Influence: 344.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rigatelli G, Zuin M, Ngo TT, Nguyen HT, Nanjundappa A, Talarico E, Duy LCP, Nguyen T. Intracoronary Cavitation as a Cause of Plaque Rupture and Thrombosis Propagation in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Computational Study. J Transl Int Med. 2019;7:69-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kannel WB, Abbott RD. Incidence and prognosis of unrecognized myocardial infarction. An update on the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1144-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 738] [Cited by in RCA: 652] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shah N, Kelly AM, Cox N, Wong C, Soon K. Myocardial Infarction in the "Young": Risk Factors, Presentation, Management and Prognosis. Heart Lung Circ. 2016;25:955-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rogers AM, Hermann LK, Booher AM, Nienaber CA, Williams DM, Kazerooni EA, Froehlich JB, O'Gara PT, Montgomery DG, Cooper JV, Harris KM, Hutchison S, Evangelista A, Isselbacher EM, Eagle KA; IRAD Investigators. Sensitivity of the aortic dissection detection risk score, a novel guideline-based tool for identification of acute aortic dissection at initial presentation: results from the international registry of acute aortic dissection. Circulation. 2011;123:2213-2218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Januzzi JL, Isselbacher EM, Fattori R, Cooper JV, Smith DE, Fang J, Eagle KA, Mehta RH, Nienaber CA, Pape LA; International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Characterizing the young patient with aortic dissection: results from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:665-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Movsowitz HD, Levine RA, Hilgenberg AD, Isselbacher EM. Transesophageal echocardiographic description of the mechanisms of aortic regurgitation in acute type A aortic dissection: implications for aortic valve repair. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:884-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang JL, Chen CC, Wang CY, Hsieh MJ, Chang SH, Lee CH, Chen DY, Hsieh IC. Acute Type A Aortic Dissection Presenting as ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Referred for Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2016;32:265-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Huang CY, Hung YP, Lin TH, Chang SL, Lee WL, Lai CH. Catheter directed diagnosis of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction induced by type A aortic dissection: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e18796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Osuga T, Parolin M S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX