Published online Nov 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i33.10315

Peer-review started: July 4, 2021

First decision: July 26, 2021

Revised: August 8, 2021

Accepted: September 22, 2021

Article in press: September 22, 2021

Published online: November 26, 2021

Processing time: 141 Days and 2.4 Hours

Acute gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is a life-threatening medical emergency with high morbidity and mortality. Transcatheter embolization with endovascular coils under digital subtraction angiography guidance is a common and effective method for the treatment of GIB with high technical success rates. Duodenal ulcers caused by coils wiggled from the branch of the gastroduodenal artery, which is a rare complication, have not previously been reported in a patient with right intrathoracic stomach.

A 62-year-old man had undergone thoracoscopy-assisted radical resection of esophageal cancer and gastroesophageal anastomosis 3 years ago, resulting in right intrathoracic stomach. He was admitted to the hospital 15 mo ago for dizziness and suffered acute GIB during his stay. Interventional surgery was urgently performed to embolize the branch of the gastroduodenal artery with endovascular coils. After 15 mo, the patient was re-admitted with a chief complaint of melena for 2 d, esophagogastroduodenoscopy and abdominal computed tomography revealed that some endovascular coils had migrated into the duodenal bulb, leading to a deep ulcer. Bleeding was controlled after conservative treatment. Seven months later, duodenal balloon dilatation was performed to relieve the stenosis after the removal of a few coils, and the patient was safely discharged with only one coil retained in the duodenum due to difficulties in complete removal and risk of bleeding. Mild melena recurred once during the long-term follow-up.

Although rare, coil wiggle after interventional therapy requires careful attention, effective precautionary measures, and more secure alternative treatment methods.

Core Tip: Acute gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is a life-threatening medical emergency with high mortality. Transcatheter embolization under digital subtraction angiography guidance is a common treatment for GIB. Herein, we report a rare case of duodenal ulcer due to coil wiggle after digital subtraction angiography-guided embolization in a patient with acute GIB who had an intrathoracic stomach due to radical resection of esophageal cancer. This case highlights that coil displacement should be considered in patients with recurrent bleeding or new gastrointestinal ulcers after interventional treatment.

- Citation: Xu S, Yang SX, Xue ZX, Xu CL, Cai ZZ, Xu CZ. Duodenal ulcer caused by coil wiggle after digital subtraction angiography-guided embolization: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(33): 10315-10322

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i33/10315.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i33.10315

Acute gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is a life-threatening medical emergency associated with a mortality rate of 8%-14%[1]. Transcatheter embolization under digital subtraction angiography (DSA) guidance has been widely considered a first-line intervention for severe GIB after failed endoscopic treatment[2]. It is a safer alternative treatment with the advantages of rapid positioning and efficiency in high-risk patients who are intolerant to surgery[3]. Endovascular coils are commonly used in DSA-guided embolization for the occlusion of targeted vessels to prevent and treat GIB due to the diversity of their size, ease of use, and better fluoroscopic visibility[4]. According to reports, the overall technical success rates of interventional transcatheter embolization in patients with active bleeding reaches 100%[5,6], whereas the clinical success rate ranges from 52% to 98%[2]. This is a widely used and mature technique in clinical practice, and the incidence and severity of complications are generally well managed. The most common complications include groin hematomas and contrast-related adverse reactions, with rates of 3%-17% and 0.04%-12.7%, respectively[7].

Coil wiggle after DSA-guided embolization has rarely been reported. Herein, we report a case of duodenal ulcer (DU) due to coil wiggle after DSA-guided embo

A 62-year-old man was admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology with melena for 2 d. Gastroscopic examination during hospitalization revealed a deep concave ulcer in the duodenal bulb with a coil-like object covered with yellow moss.

The patient passed a small amount of dark and tarry stools without obvious induction 2 d before presentation, without abdominal pain or hematemesis.

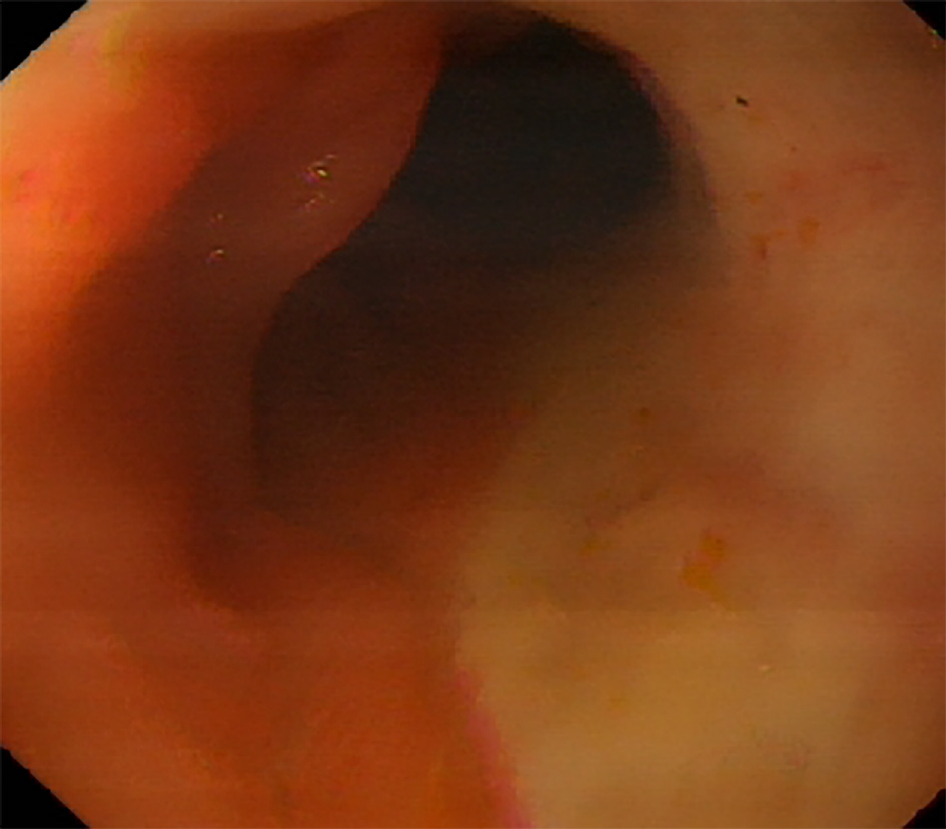

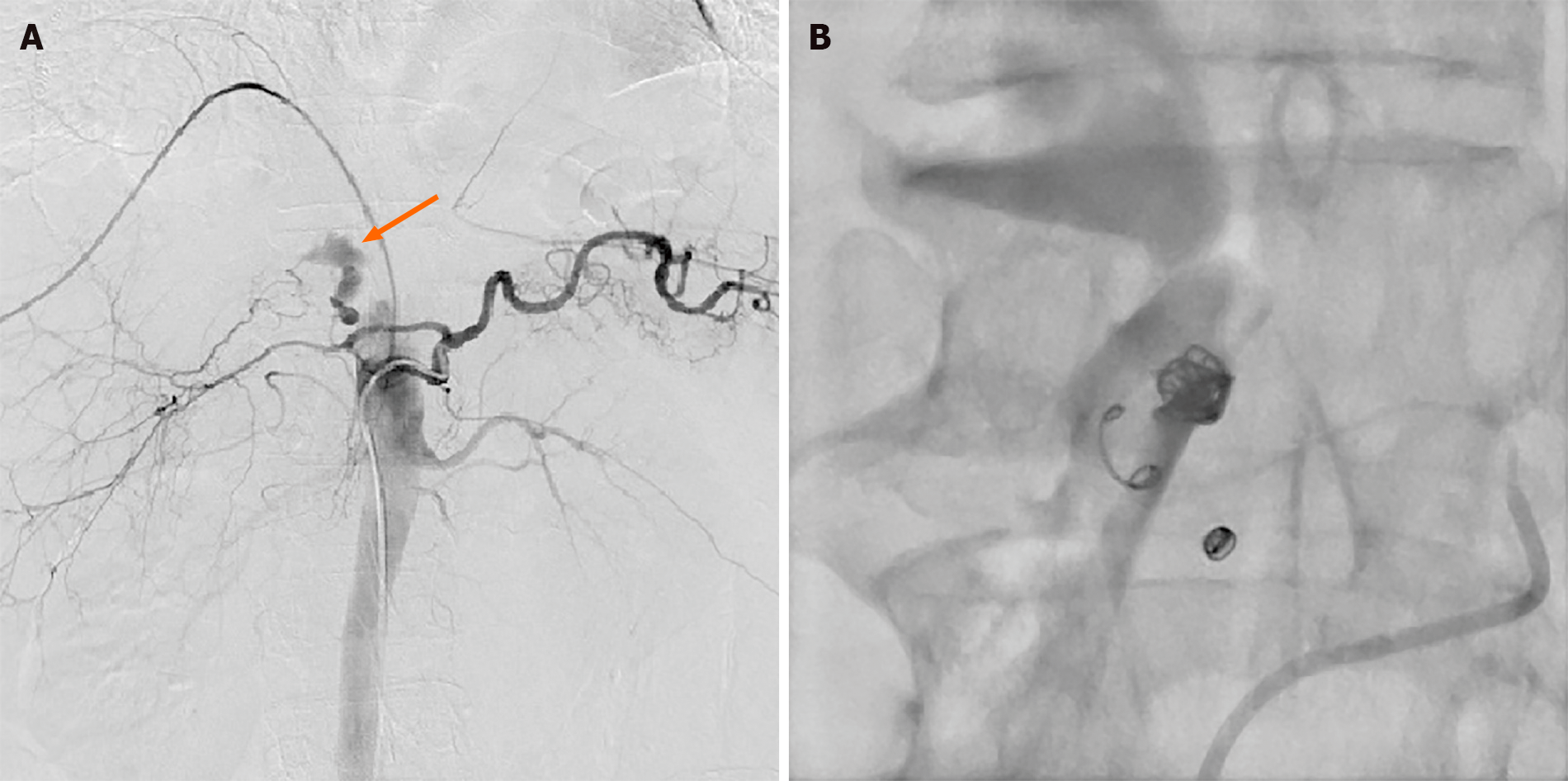

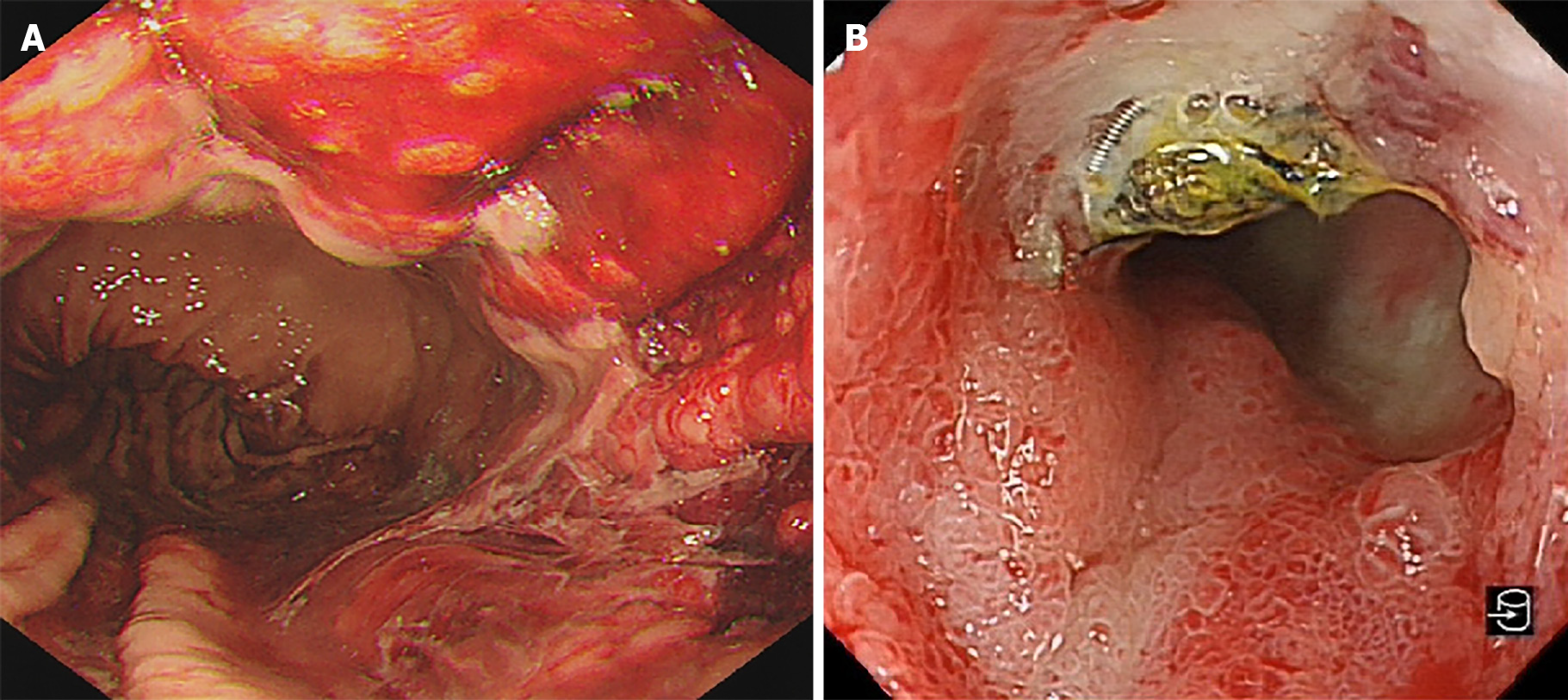

The patient underwent thoracoscopy-assisted radical resection of esophageal cancer and gastroesophageal anastomosis 3 years ago, in which the stomach and part of the duodenum were lifted to the right thorax. Approximately 15 mo before the current hospitalization for GIB, he was admitted to the oncology radiochemotherapy department due to dizziness. On admission, the patient had a hemoglobin level of only 37 g/L and a positive fecal occult blood test finding, which suggested the possibility of GIB. The patient underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy, which showed that the duodenal bulb was covered with a layer of dirty yellow moss, but no signs of bleeding were found (Figure 1). With the transfusion of blood products, the patient's hemoglobin gradually recovered to 96 g/L, and his condition seemed to improve significantly. However, the patient experienced an episode of acute hematochezia and hematemesis on post-treatment day 9. After losing 2200 mL blood in just 30 min, his blood pressure dropped to 8.0/5.3 kPa and he entered a state of shock. Consultation with the gastroenterology and DSA departments indicated the possibility of acute hemorrhage in the small intestine, reaching a consensus that interventional treatment would be more likely to be beneficial. After receiving anti-shock treatment in the ward, the patient was rushed to the DSA room. Angiography showed extravasation of the contrast agent into the branch of the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) (Figure 2A). After selective probing of the bleeding artery, four embolization microcoils sized 3 mm × 3.3 mm, two embolization microcoils sized 4 mm × 3.7 mm, and two embolization microcoils sized 6 mm × 6.7 mm were selected to embolize the bleeding vessel. Complete occlusion was validated using DSA (Figure 2B). Gastroscopic examination on the following day revealed diffuse congestion and swelling of the mucosa in the gastric corpus, accompanied by diffuse erosion. Venous congestion formed a clear boundary with bloody fluid attached to the surface (Figure 3A). No active bleeding was observed after rinsing with ice-cold water. Unfortunately, due to the presence of bloody fluid and yellow mucus, pictures of the duodenal bulb were not obtained. No postoperative GIB occurred, and the patient was discharged 19 d later.

The patient had a free personal and family history.

At admission, the patient's temperature was 36.5 °C, pulse was 78 beats/min, respiratory rate was 20 beats/min, and blood pressure was 15.7/9.4 kPa. The abdomen was flat and soft, and there was no tenderness or rebound pain in the entire abdomen. The spleen and liver were not palpable, and no blood vessel noise was observed. The borborygmus was slightly active.

Hospitalization for dizziness: On admission, routine blood tests showed severe hemoglobin reduction of only 39 g/L, red blood cell (RBC) count of 1.43 × 1012/L, and white blood cell (WBC) and platelet counts within the normal range. C-reactive protein level was not elevated. Blood biochemical results indicated normal transaminase, creatinine, and alkaline phosphatase levels. No abnormal coagulation indices were observed. After transfusion and fluid replacement, the hemoglobin level increased to 96 g/L and RBC count increased to 3.10 × 1012/L. Seven days after severe GIB, hemoglobin level again decreased to 66 g/L, C-reactive protein level peaked at 58.3 g/L, and WBC count increased to 27.6 × 109/L. Fortunately, with active treatment, the patient's anemia improved significantly, inflammatory marker levels returned to normal, and the patient was discharged under acceptable conditions.

Hospitalization for melena: Blood analysis revealed that neutrophil granulocytes increased to 81.8% with hemoglobin level, blood platelet count, and RBC count in the normal range. Prothrombin level, d-dimer level, and partial thromboplastin time were normal. Further, serum C-reactive protein level increased at 17.74 mg/L (normal range, < 8 mg/L).

Chest computed tomography (CT) showed the right intrathoracic stomach and a small amount of effusion in both pleural cavities. After he was transferred to the operating room due to GIB, DSA was performed on the celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery, and inferior mesenteric artery. Since the stomach and part of the duodenum were in the thoracic cavity, the vessels supplying to the stomach and duodenum flowed in the direction of the diaphragm on the angiographic image, and extravasation of contrast agent was found in the branch of the GDA during the operation (Figure 2A). After selective probing of the bleeding artery, four embolization microcoils sized 3 mm × 3.3 mm, two embolization microcoils sized 4 mm × 3.7 mm, and two embolization microcoils sized 6 mm × 6.7 mm were selected to embolize the bleeding vessel. Complete occlusion was validated using angiography (Figure 2B).

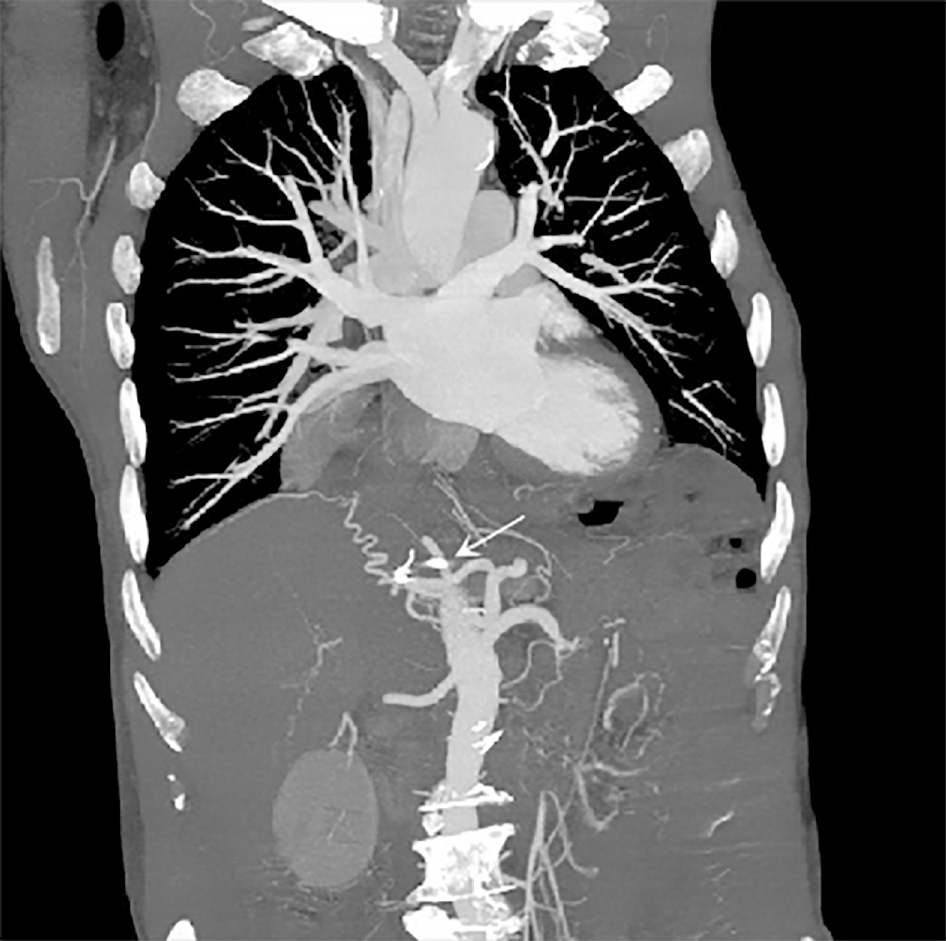

The patient was hospitalized for GIB again 15 mo later, and esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a deep concave ulcer in the deformed and stenotic duodenal bulb with a coil-like object covered with yellow moss (Figure 3B). It was hypothesized that the ulcer was caused by the wiggle of coils. This was confirmed by abdominal CT that revealed two radiating metallic dense shadows, one of which was located in the duodenal bulb. However, the exact number of displaced coils could not be estimated (Figure 4).

Hospitalization for dizziness: DSA imaging showed extravasation of contrast agent in the branch of the GDA, but esophagogastroduodenoscopy performed before the hemorrhage failed to identify bleeding source. The cause of the first episode of acute GIB was considered and discussed by doctors. However, based on the available evidence, doctors could not draw firm conclusions. The following hypotheses were proposed: First, there was a bleeding spot covered by yellow moss that was temporarily inactive and could not be detected by examiners. Second, the presence of a bleeding spot in the distal duodenum or small intestine, which cannot be reached by esophagogastroduodenoscopy, was another hypothesis.

Hospitalization for melena: According to the patient's history of DSA-guided embolization, with the results of this esophagogastroduodenoscopy examination and CT report, the abnormally dark, tarry stool was due to the ulcer caused by the coil displacement into the duodenal bulb.

Considering the significant bleeding risk associated with coil removal during endoscopy, we conducted a multidisciplinary discussion. The DSA surgeon indicated that they were unable to provide further treatment and recommended consultation with the gastrointestinal surgery department, which believed that the coil could be removed by surgery. However, after careful consideration, the patient's family refused surgical treatment and chose conservative treatment. After treatment with fasting, fluid rehydration, proton pump inhibitor treatment, and gastric mucosal protectant, the patient was discharged after 9 d in the hospital.

The patient visited our hospital for esophagogastroduodenoscopy reexamination 7 mo later and was in good condition without GIB symptoms. After evaluation by the DSA department, the risk of bleeding was considered to be small, and endoscopic treatment was attempted. Two of the coils were removed without incident by an experienced endoscopic physician, leaving only one visible coil in the duodenal bulb due to difficulties in complete removal and risk of bleeding. Coils that could not be observed by endoscopy were not removed.

Subsequently, balloon dilation was performed to relieve duodenal bulb stenosis. The patient recovered well after coil removal and was discharged safely. At the follow-up visit, mild melena recurred, but was well controlled by medication. The patient expressed gratitude and satisfaction with treatment.

GIB is a common clinical emergency that may be fatal in severe cases with high morbidity and mortality. GIB management includes drug therapy, endoscopy, intervention, and surgery. The efficacy of drug therapy is definite. Patients can achieve cost-effective outcomes after regular medication, especially those with a likelihood of high-risk lesions, reducing the need for endoscopic therapy[8,9]. Endoscopy is the best initial method for the diagnosis and treatment of upper GIB. GIB can be diagnosed through endoscopy in 95% of cases, with a therapeutic effect achieved in 90% of cases[10]. For management of severe or refractory GIB, intervention or surgery may be required instead of repeat therapeutic endoscopy[11]. In a hemodynamically unstable state with the possibility of lower GIB, transcatheter arteriography or intervention treatment could be a safer choice.

DSA and arterial embolization techniques can provide less invasive options for patients with mass GIB, for which the primary success rate is quite high. Further, 10%-20% of patients with recurrent bleeding require repeated embolization[12]. Common complications of arterial embolization include recurrent bleeding and gastrointestinal ischemia[13]. Coil wiggle after DSA-guided embolization has rarely been reported as a complication. In a report by Kao et al[14], a 65-year-old woman developed a pseudoaneurysm after cholecystectomy with T-tube choledochostomy, which resulted in biliary hemorrhage. The patient eventually underwent embolization. Eight years later, abdominal CT revealed a coil-like density in the hilar area with dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts. The patient underwent percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage due to obstructive jaundice. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) revealed five microcoils around the hepatic hilum. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation was performed, several mixed stones were removed by the basket, and a microcoil was found in one of the stone fragments[14]. Our case reported the first case of coil displacement in a patient with right intrathoracic stomach and GIB, but similar events have been reported in patients with normal anatomical structures. In a report by Skipworth et al[15], a 55-year-old man was discharged from the hospital after receiving coil embolization for a gastroduodenal aneurysm. During outpatient follow-up, the doctor found tenderness in the patient's upper abdomen. Gastrograffin indicated a pyloric outlet and duodenal obstruction. ERCP indicated coils in the pyloric area, accompanied by ulcer formation. Unable to remove the coils endoscopically, the doctors performed sphincterotomy. The patient was safely discharged after symptom remission[15]. The patient in our case report experienced an acute attack of GIB and hemorrhagic shock, but esophagogastroduodenoscopy performed 7 d earlier failed to identify any bleeding site. Consultation of the gastroenterology and DSA department suggested the possibility of small intestinal bleeding. Hematemesis, hematochezia, and even hemorrhagic shock may also occur in severe cases with massive bleeding in the small intestine. According to the ACR Appropriateness Criteria[16], transcatheter arteriography or intervention treatment is likely more appropriate and beneficial for a hemodynamically unstable patient with small intestinal bleeding. In this condition, intervention is considered the safest. Hemostatic measures could be initiated immediately after the bleeding site was identified using DSA, regardless of the presence of upper or lower GIB. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was riskier because of the time lost during the procedure if the bleeding site failed to be identified in the upper digestive tract. Therefore, the patient underwent interventional treatment and had several coils embolized into the branch of the GDA. Fifteen months later, esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed that several endovascular coils have incarcerated in the duodenum and caused ulceration. Doctors did not rule out the possibility that the coil gradually wiggled from the initial location to the position near the duodenal bulb and caused the rupture of the blood vessels. Owing to the thin wall of the duodenal bulb, the coil gradually penetrated and settled down. The phenomenon of coil displacement in this patient may be due to the fact that the esophagus surgery changed the anatomical position of the digestive tract and the normal vascular distribution structure, and the curved blood vessels were straightened, thus facilitating movement of the coil. Since the bleeding stopped after the drug treatment, there was no special treatment for the coil. Seven months later, the patient underwent endoscopic therapy after assessing the risk of bleeding, and two migrated coils in the duodenum were removed.

This case report has several limitations. First, images of the duodenal bulb on the day after interventional treatment were not obtained because of obscurity caused by the bloody fluid and yellow moss, which resulted in our inability to estimate if there was ulcer formation or ischemic change after interventional therapy. Second, the coils removed with the endoscope were not recorded or retained, so we were unable to confirm which embolized coils were penetrating the duodenum. Obviously, information regarding the migrated coils could be useful in developing effective measures.

Patients may develop imprudent arterial embolization in the long term. Therefore, its indications and surgical modalities should be clearly defined and scrutinized, and new interventions and materials such as vascular filters should be considered and expedited to cope with potential coil wiggle. The possibility of coil displacement may be greater in patients with changes in the anatomic position of blood vessels. Surgeons should carefully select the embolization site and coil size. The placement of coils of the proper size in the winding vessels could possibly reduce the risk. For recurrent bleeding or ulcers after DSA surgery, doctors should be cautious about the possibility of coil displacement.

Although coil wiggle after interventional therapy is rare, it still requires attention. For recurrent bleeding or ulcers after DSA surgery, caution should be given to the possibility of embolic displacement. The research and development of new interventional methods and materials should be accelerated to reduce the probability of such events and improve patient prognosis.

I sincerely thank Ye MS for her discovery of this case and Ni RJ for beautifying the pictures.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shimodaira Y, Yoshikawa T S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Guo X

| 1. | Choi C, Lim H, Kim MJ, Lee BY, Kim SY, Soh JS, Kang HS, Moon SH, Kim JH. Relationship between angiography timing and angiographic visualization of extravasation in patients with acute non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Loffroy R, Favelier S, Pottecher P, Estivalet L, Genson PY, Gehin S, Cercueil JP, Krausé D. Transcatheter arterial embolization for acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Indications, techniques and outcomes. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96:731-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Loffroy R, Guiu B, Cercueil JP, Lepage C, Latournerie M, Hillon P, Rat P, Ricolfi F, Krausé D. Refractory bleeding from gastroduodenal ulcers: arterial embolization in high-operative-risk patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:361-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shin JH. Recent update of embolization of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13 Suppl 1:S31-S39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shi ZX, Yang J, Liang HW, Cai ZH, Bai B. Emergency transcatheter arterial embolization for massive gastrointestinal arterial hemorrhage. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e9437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Spiliopoulos S, Inchingolo R, Lucatelli P, Iezzi R, Diamantopoulos A, Posa A, Barry B, Ricci C, Cini M, Konstantos C, Palialexis K, Reppas L, Trikola A, Nardella M, Adam A, Brountzos E. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization for Bleeding Peptic Ulcers: A Multicenter Study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41:1333-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Loffroy R, Rao P, Ota S, De Lin M, Kwak BK, Geschwind JF. Embolization of acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage resistant to endoscopic treatment: results and predictors of recurrent bleeding. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:1088-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Al-Sabah S, Barkun AN, Herba K, Adam V, Fallone C, Mayrand S, Pomier-Layrargues G, Kennedy W, Bardou M. Cost-effectiveness of proton-pump inhibition before endoscopy in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:418-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gralnek IM, Dumonceau JM, Kuipers EJ, Lanas A, Sanders DS, Kurien M, Rotondano G, Hucl T, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Marmo R, Racz I, Arezzo A, Hoffmann RT, Lesur G, de Franchis R, Aabakken L, Veitch A, Radaelli F, Salgueiro P, Cardoso R, Maia L, Zullo A, Cipolletta L, Hassan C. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:a1-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Foltz G, Khaddash T. Embolization of Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Complicated by Bowel Ischemia. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2019;36:76-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Laine L, Jensen DM. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:345-60; quiz 361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 498] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Loffroy R, Guiu B, D'Athis P, Mezzetta L, Gagnaire A, Jouve JL, Ortega-Deballon P, Cheynel N, Cercueil JP, Krausé D. Arterial embolotherapy for endoscopically unmanageable acute gastroduodenal hemorrhage: predictors of early rebleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:515-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mensel B, Kühn JP, Kraft M, Rosenberg C, Ivo Partecke L, Hosten N, Puls R. Selective microcoil embolization of arterial gastrointestinal bleeding in the acute situation: outcome, complications, and factors affecting treatment success. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:155-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kao WY, Chiou YY, Chen TS. Coil migration into the common bile duct after embolization of a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E364-E365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Skipworth JR, Morkane C, Raptis DA, Kennedy L, Johal K, Pendse D, Brennand DJ, Olde Damink S, Malago M, Shankar A, Imber C. Coil migration--a rare complication of endovascular exclusion of visceral artery pseudoaneurysms and aneurysms. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:e19-e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Expert Panel on Interventional Radiology; Karuppasamy K, Kapoor BS, Fidelman N, Abujudeh H, Bartel TB, Caplin DM, Cash BD, Citron SJ, Farsad K, Gajjar AH, Guimaraes MS, Gupta A, Higgins M, Marin D, Patel PJ, Pietryga JA, Rochon PJ, Stadtlander KS, Suranyi PS, Lorenz JM. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Radiologic Management of Lower Gastrointestinal Tract Bleeding: 2021 Update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18:S139-S152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |