Published online Nov 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.10046

Peer-review started: August 12, 2021

First decision: September 2, 2021

Revised: September 8, 2021

Accepted: September 22, 2021

Article in press: September 22, 2021

Published online: November 16, 2021

Processing time: 89 Days and 17.6 Hours

Jaundice is a major manifestation of posthepatectomy liver failure, a feared complication after hepatic resection. Herein, we report a case of posthepatectomy jaundice that was not caused by liver failure but by paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH)-induced hemolysis.

A 56-year-old woman underwent right hepatectomy and biliary tract exploration surgery due to hepatic duct stones. Prior to surgery, the patient was mildly anemic. The direct antiglobulin test was negative. A bone marrow biopsy showed mild histiocyte hyperplasia. After surgery, the patient suffered a progressive increase in serum bilirubin. Meanwhile, the patient developed hemolytic symptoms after blood transfusion. She was ultimately diagnosed with PNH. PNH is a rare bone marrow failure disorder that manifests as complement-dependent intravascular hemolysis with varying severity. After steroid treatment, the patient’s jaundice gradually decreased, and the patient was discharged on the 35th postoperative day.

PNH-induced hemolysis is a rare cause of posthepatectomy jaundice. It should be suspected in patients having posthepatectomy hyperbilirubinemia without other signs of liver failure. Steroid therapy can be considered for the treatment of PNH in such cases.

Core Tip: We report a case of posthepatectomy jaundice that was not caused by liver failure but by paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria-induced hemolysis. After confirming the diagnosis, the patient received steroid therapy, and the jaundice gradually improved.

- Citation: Liang HY, Xie XD, Jing GX, Wang M, Yu Y, Cui JF. Posthepatectomy jaundice induced by paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(32): 10046-10051

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i32/10046.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.10046

Although the safety of liver resection has improved with advanced operative techniques and perioperative management, posthepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) remains a challenge for patients undergoing hepatectomy and a concern of hepatic surgeons[1]. Postoperative hyperbilirubinemia and an increased international normalized ratio (INR) are the major manifestations of PHLF according to the definition of the International Study Group of Liver Surgery[2]. Herein, we report a case of posthepatectomy jaundice that was not caused by PHLF but by paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH)-induced hemolysis. There have been no previous reports of posthepatectomy jaundice caused by PNH.

The subject was a 56-year-old female with a chief complaint of abdominal pain and fever.

Ten days before admission, the patient visited a local hospital for acute right upper quadrant abdominal pain. The pain was moderate, tolerable, and persistent. Additionally, the patient suffered from fever, with a temperature of up to 39 degrees Celsius. She did not complain of vomiting or diarrhea. An abdominal ultrasound revealed bile duct stones. After cefoperazone anti-infection treatment, the patient’s symptoms were relieved, and the patient was transferred to our hospital.

The patient had undergone cholecystectomy for gallbladder stones 20 years prior to presentation at our hospital.

The patient had a previous history of mild anemia and did not have a remarkable family medical history.

On physical examination, the patient was conscious and cooperative. The abdominal region was flat and soft.

The patient’s preoperative laboratory examinations were only mildly abnormal: Hemoglobin (Hgb) 91 g/L, white blood cell count, 9800/μL; platelet count, 107 × 109/L; total bilirubin (TBIL), 58.6 µmol/L; direct bilirubin (DBIL), 35.3 µmol/L; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 33.5 U/L; albumin, 38.7 g/L; C-reactive protein, 32.4 mg/dL; prothrombin time, 10.8 s; INR, 0.98; indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min, 5.5%. The result of direct antiglobulin test was negative, and bone marrow biopsy showed mild histiocyte hyperplasia.

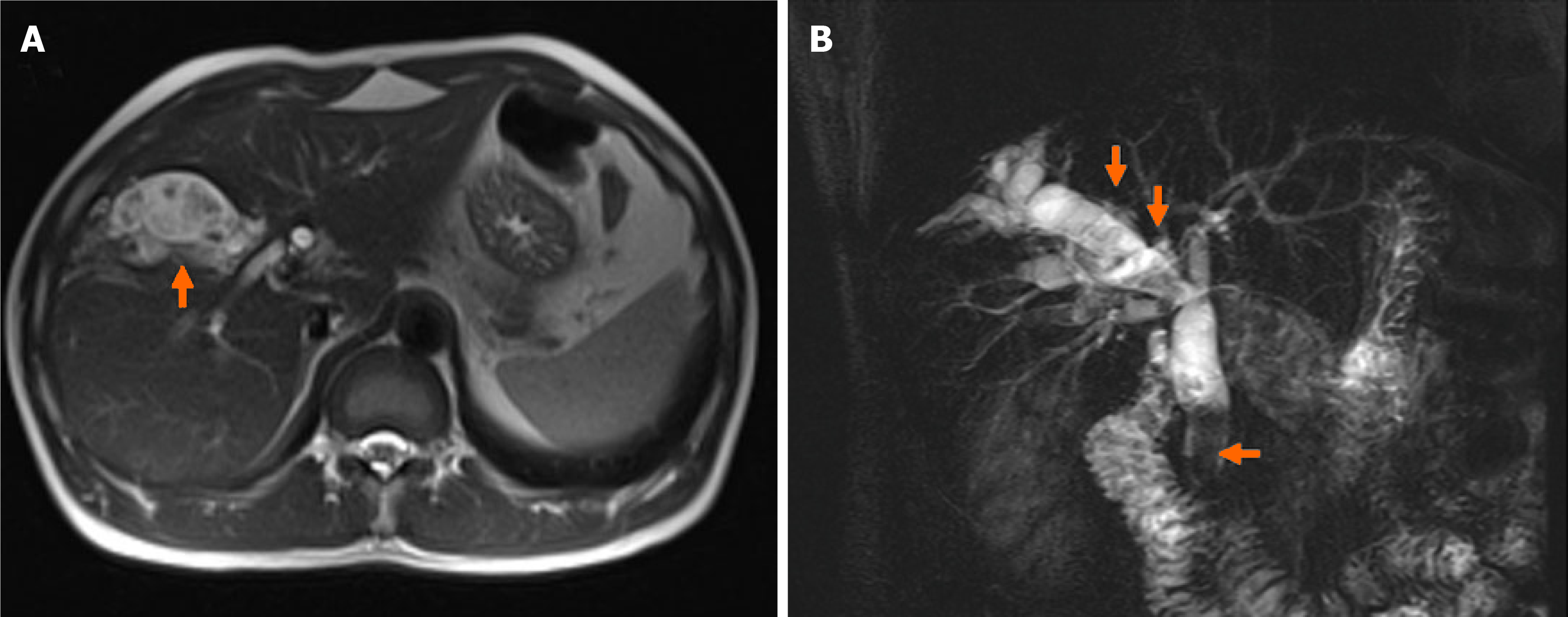

Magnetic resonance imaging revealed right intrahepatic bile duct stones and common bile duct stones (Figure 1). The future liver remnant was 49%.

The patient was diagnosed with hepatolithiasis and choledocholithiasis. After surgery, she was diagnosed to have PNH induced hemolysis causing postoperative jaundice.

Open surgery was performed after the preoperative examinations were completed. Intraoperative ultrasonography reconfirmed that the right intrahepatic bile duct was extensively dilated with stones. The common bile duct was approximately 1.4 cm. Eventually, right hepatectomy and biliary tract exploration with intraoperative choledochoscopic lithotripsy, without hepaticojejunostomy, were conducted. The operation proceeded successfully without a requirement for blood transfusion. The operating time was 250 min, and the estimated blood loss was less than 100 mL.

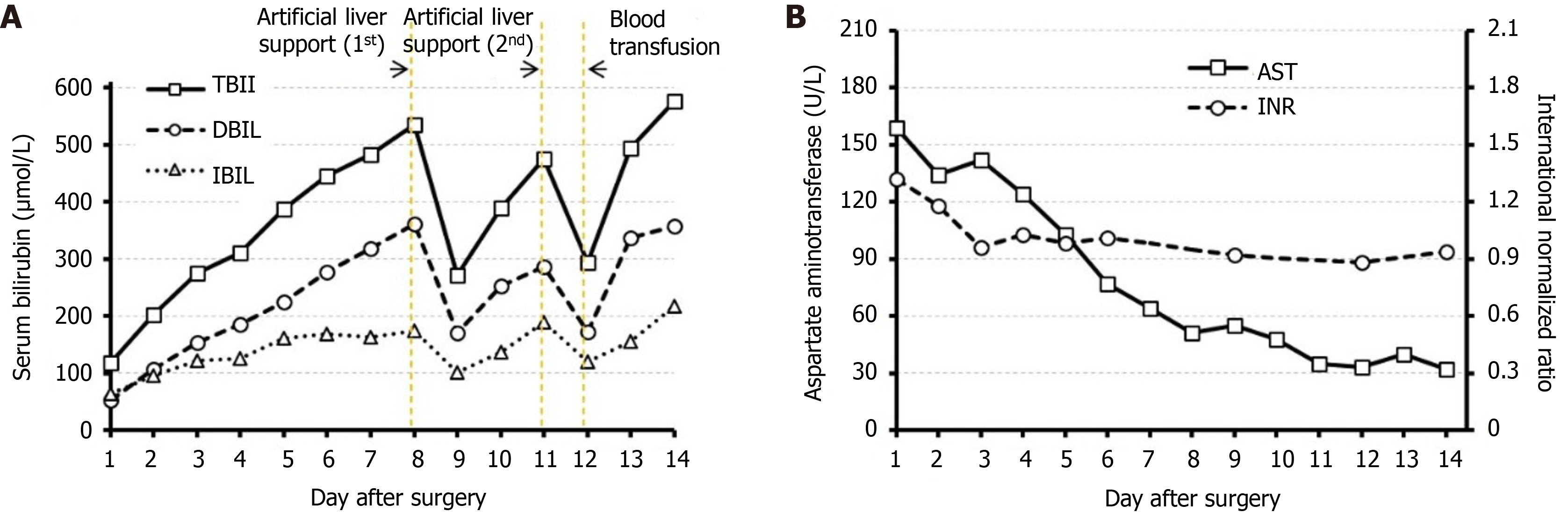

An artificial liver support system was required on the 8th and 11th postoperative days due to hyperbilirubinemia. The patient received a blood transfusion (erythrocyte suspensions, 3 U; and plasma, 400 mL) because of a decrease in Hgb to 65 g/L on the 12th postoperative day.

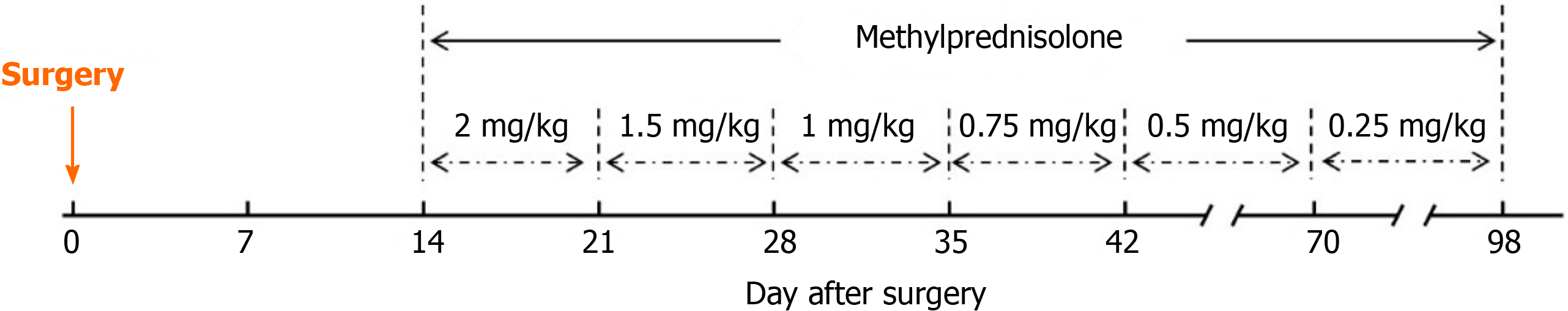

The patient was treated with steroids after the diagnosis of postoperative jaundice caused by PNH induced hemolysis was made. The treatment protocol is shown in Figure 2. On postoperative day 14, the patient started steroid treatment with methylprednisolone at a dose of 2.0 mg/kg/d. The patient's jaundice gradually stabilized. The dose of methylprednisolone was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg/d after 1 wk, 1.0 mg/kg/d after 2 wk, 0.75 mg/kg/d after 3 wk, and 0.5 mg/kg/d after 4 wk. The dose of 0.5 mg/kg/d was maintained for 4 wk, and 0.25 mg/kg/d was maintained for an additional 4 wk.

After surgery, the patient suffered a progressive increase in serum bilirubin (Figure 3A). Paradoxically, the AST and INR were mildly elevated postoperatively and declined gradually (Figure 3B). Postoperative ultrasound did not reveal intra- or extrahepatic bile duct dilatation. These results did not resemble the typical present

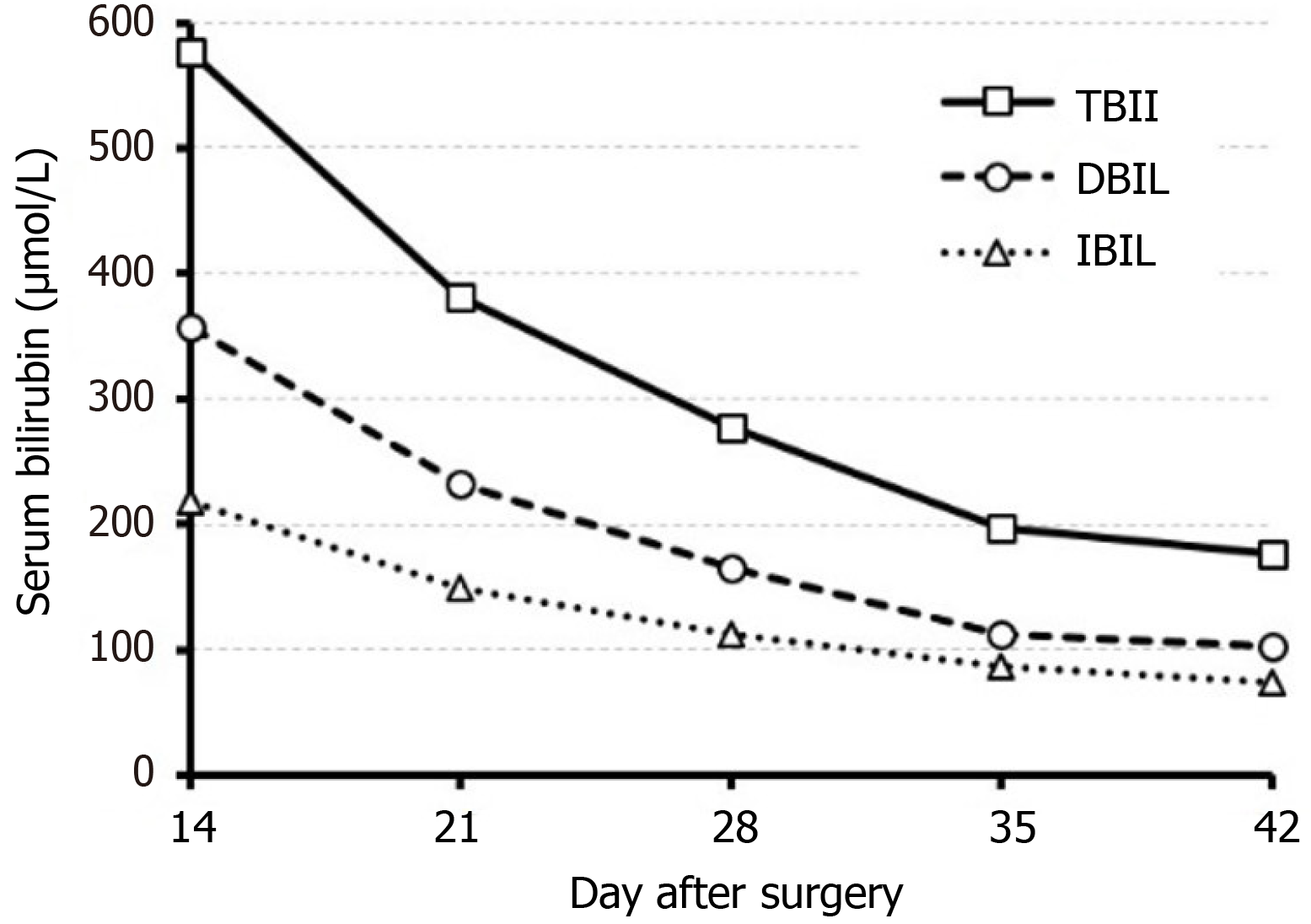

The patient's jaundice gradually improved after steroid treatment (Figure 4). The patient was discharged on the 35th postoperative day. At discharge, the TBIL of the patient had decreased to 198.3 µmol/L. When followed up at 6 mo after surgery, the patient's Hgb was 85 g/L, and TBIL was 48.3 µmol/L.

PNH is a rare and acquired hematopoietic stem cell disorder that is characterized by the destruction of blood cells via the complement system due to a deficiency of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins (GPI-APs), such as CD55 and CD59, on the blood cell surface, resulting in symptoms such as hemoglobinuria[3]. For the diagnosis of PNH, flow cytometry is recommended to identify a deficiency of GPI-APs in peripheral blood cells[4,5]. In this patient, CD59 absence on the surface of 27% of erythrocytes was an important factor in the diagnosis of PHN. In terms of treatment, complement inhibition therapy in the form of eculizumab has improved treatment prospects for PNH patients in developed countries[6,7]. However, high costs and access difficulties have limited the utilization of eculizumab in China, and steroid therapy is still the preferred treatment to control hemolytic attacks in PNH patients[8]. In this case, the patient's hyperbilirubinemia was relieved after the administration of methylprednisolone, and the treatment achieved relatively favorable outcomes.

There were several points that deserve our attention in this case.

First, the severity of hemolysis varies in PNH patients. There are some PNH patients with insidious onset that have no characteristic manifestations[9]. This patient only presented with mild anemia and elevated bilirubin preoperatively, which is also common in patients with bile duct stones. Moreover, the preoperative bone marrow biopsy showed no significant abnormalities. The patient was not diagnosed with PNH until hemolytic symptoms developed after blood transfusion.

Second, in this patient, it is possible that transfusion of plasma, rather than erythrocyte suspension, aggravated the patient’s hemolysis. PNH may induce complement-dependent intravascular hemolysis[10]. Plasma transfusion might replenish the depleted complement, thus exacerbating the occurrence of hemolysis in PNH erythrocytes. Although the use of washed red blood cells for transfusion in PNH patients has been recommended previously, recent studies have found that transfusion of homozygous red blood cells does not significantly increase the occurrence of hemolysis in PNH patients[11].

Third, it has been reported that chronic hemolysis may lead to increased bilirubin excretion, resulting in an increased incidence of hepatobiliary stones[12]. Therefore, theoretically, PNH patients have a higher chance of hepatobiliary stones. There have been reports of cholecystectomy in patients with PNH[13], but there have been no reports of hepatectomy in patients with PNH. Surgery may be one of the clinical conditions that triggers PNH-induced hemolysis[14]. Perisurgical induction of eculizumab has been reported in a patient with PNH to inhibit surgery-triggered hemolysis[13,15].

Last, the jaundice caused by hemolysis typically features elevated indirect bilirubin (IBIL)[16]. However, the postoperative DBIL elevation was more significant in this patient. The liver is the main metabolic site for bilirubin. The IBIL produced by hemolysis is transported to hepatocytes and combined with glucuronide to form DBIL, which is subsequently excreted into the bile ducts[17]. Right hemicolectomy may lead to a reduction in liver size and a decrease in the liver’s ability to metabolize and excrete bilirubin. In the event of increased IBIL production from hemolysis, it is possible that the residual hepatic capacity to metabolize DBIL is greater than the hepatic capacity to excrete DBIL. This has not been reported in previous reports and may need to be validated in further animal experiments.

PNH-induced hemolysis is a rare cause of posthepatectomy jaundice. It should be suspected in patients having posthepatectomy hyperbilirubinemia without other signs of liver failure. Steroid therapy can be considered for the treatment of PNH in such cases.

| 1. | Søreide JA, Deshpande R. Post hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) - Recent advances in prevention and clinical management. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47:216-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Rahbari NN, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Brooke-Smith M, Crawford M, Adam R, Koch M, Makuuchi M, Dematteo RP, Christophi C, Banting S, Usatoff V, Nagino M, Maddern G, Hugh TJ, Vauthey JN, Greig P, Rees M, Yokoyama Y, Fan ST, Nimura Y, Figueras J, Capussotti L, Büchler MW, Weitz J. Posthepatectomy liver failure: a definition and grading by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS). Surgery. 2011;149:713-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1224] [Cited by in RCA: 1821] [Article Influence: 121.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Devalet B, Mullier F, Chatelain B, Dogné JM, Chatelain C. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: a review. Eur J Haematol. 2015;95:190-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Parker C, Omine M, Richards S, Nishimura J, Bessler M, Ware R, Hillmen P, Luzzatto L, Young N, Kinoshita T, Rosse W, Socié G; International PNH Interest Group. Diagnosis and management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2005;106:3699-3709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Parker CJ. Update on the diagnosis and management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016;2016:208-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hillmen P, Young NS, Schubert J, Brodsky RA, Socié G, Muus P, Röth A, Szer J, Elebute MO, Nakamura R, Browne P, Risitano AM, Hill A, Schrezenmeier H, Fu CL, Maciejewski J, Rollins SA, Mojcik CF, Rother RP, Luzzatto L. The complement inhibitor eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1233-1243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 855] [Cited by in RCA: 934] [Article Influence: 46.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Loschi M, Porcher R, Barraco F, Terriou L, Mohty M, de Guibert S, Mahe B, Lemal R, Dumas PY, Etienne G, Jardin F, Royer B, Bordessoule D, Rohrlich PS, Fornecker LM, Salanoubat C, Maury S, Cahn JY, Vincent L, Sene T, Rigaudeau S, Nguyen S, Lepretre AC, Mary JY, Corront B, Socie G, Peffault de Latour R. Impact of eculizumab treatment on paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: a treatment vs no-treatment study. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:366-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fu R, Li L, Liu H, Zhang T, Ding S, Wang G, Song J, Wang H, Xing L, Guan J, Shao Z. Analysis of clinical characteristics of 92 patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: A single institution experience in China. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34:e23008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brodsky RA. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2014;124:2804-2811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Merrill SA, Brodsky RA. Complement-driven anemia: more than just paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2018;2018:371-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Brecher ME, Taswell HF. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and the transfusion of washed red cells. A myth revisited. Transfusion. 1989;29:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ebert EC, Nagar M, Hagspiel KD. Gastrointestinal and hepatic complications of sickle cell disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:483-9; quiz e70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ando K, Gotoh A, Yoshizawa S, Gotoh M, Iwabuchi T, Ito Y, Ohyashiki K. Successful cholecystectomy in a patient with aplastic anemia-paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria during eculizumab treatment. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1987-1988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kurita N, Obara N, Fukuda K, Nishikii H, Sato S, Inagawa S, Kurokawa T, Owada Y, Ninomiya H, Chiba S. Perisurgical induction of eculizumab in a patient with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: its inhibition of surgery-triggered hemolysis and the consequence of subsequent discontinuation. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24:658-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Parker CJ. Management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria in the era of complement inhibitory therapy. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:21-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rifkind JM, Nagababu E. Hemoglobin redox reactions and red blood cell aging. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:2274-2283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kosmachevskaya OV, Topunov AF. Alternate and Additional Functions of Erythrocyte Hemoglobin. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2018;83:1575-1593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kamiyama T S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH