Published online Nov 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i31.9623

Peer-review started: May 6, 2021

First decision: July 5, 2021

Revised: July 11, 2021

Accepted: September 8, 2021

Article in press: September 8, 2021

Published online: November 6, 2021

Processing time: 176 Days and 0.7 Hours

Bilateral perirenal hematoma is rarely reported in endoscopic management of horseshoe kidney stones, and there are few studies reporting the formation of bilateral hematoma following tubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) for unilateral horseshoe kidney calculi.

A 32-year-old man was admitted to our hospital because of repeated intermittent hematuria for 10 years. Plain abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed calculi in the horseshoe kidney; the largest being 2 cm in diameter. Tubeless PCNL was performed to remove the stones. Three days after the operation, the patient was discharged in a stable situation. Three days after discharge, the patient presented to our emergency department because of right low back pain and vomiting. Emergent CT scan revealed subcapsular and perirenal hematocele and exudates in both kidneys. Ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage of perirenal effusion were performed. After the temperature stabilized, the patient received low-pressure injection of urokinase 100000 U for 3 d. His routine blood indexes and the renal function returned to normal in 3 wk. CT re-examination 3 mo after lithotripsy showed that the subcapsular and perirenal hematoma and exudates in both kidneys were significantly absorbed as compared with those before. The patient was followed up for 1 year, during which no flank pain or hematuria recurred.

This is the first case report on the formation of bilateral hematoma following tubeless PCNL for unilateral horseshoe kidney calculi.

Core Tip: Minimally invasive urological techniques, such as retrograde intrarenal surgery, percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, have been applied for the treatment of horseshoe kidney stones, but they all have their respective advantages and disadvantages in terms of efficacy and postoperative complications. To the best of our knowledge, there is no study reporting the formation of bilateral hematoma following tubeless PCNL for unilateral horseshoe kidney calculi. Our experience in treating this patient can be summarized as six points, which are a good reference for readers.

- Citation: Zhou C, Yan ZJ, Cheng Y, Jiang JH. Bilateral hematoma after tubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomy for unilateral horseshoe kidney stones: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(31): 9623-9628

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i31/9623.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i31.9623

The traditional treatment for horseshoe kidney stones is open surgery[1], during which the ureter or isthmus is released so that the kidney and the ureter restore their normal positions. Minimally invasive urological techniques, such as retrograde intrarenal surgery, percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, have been applied for the treatment of horseshoe kidney stones[2], but they all have their respective advantages and disadvantages in terms of the efficacy and postoperative complications. In August 2019, a patient with a horseshoe kidney complicated with kidney stones was admitted to our hospital. One week after tubeless PCNL on one side, the patient developed massive subcapsular bleeding on the affected side and subcapsular bleeding on the other side, which is a rarely encountered situation in clinical practice.

A 32-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital because of repeated intermittent hematuria for 10 years.

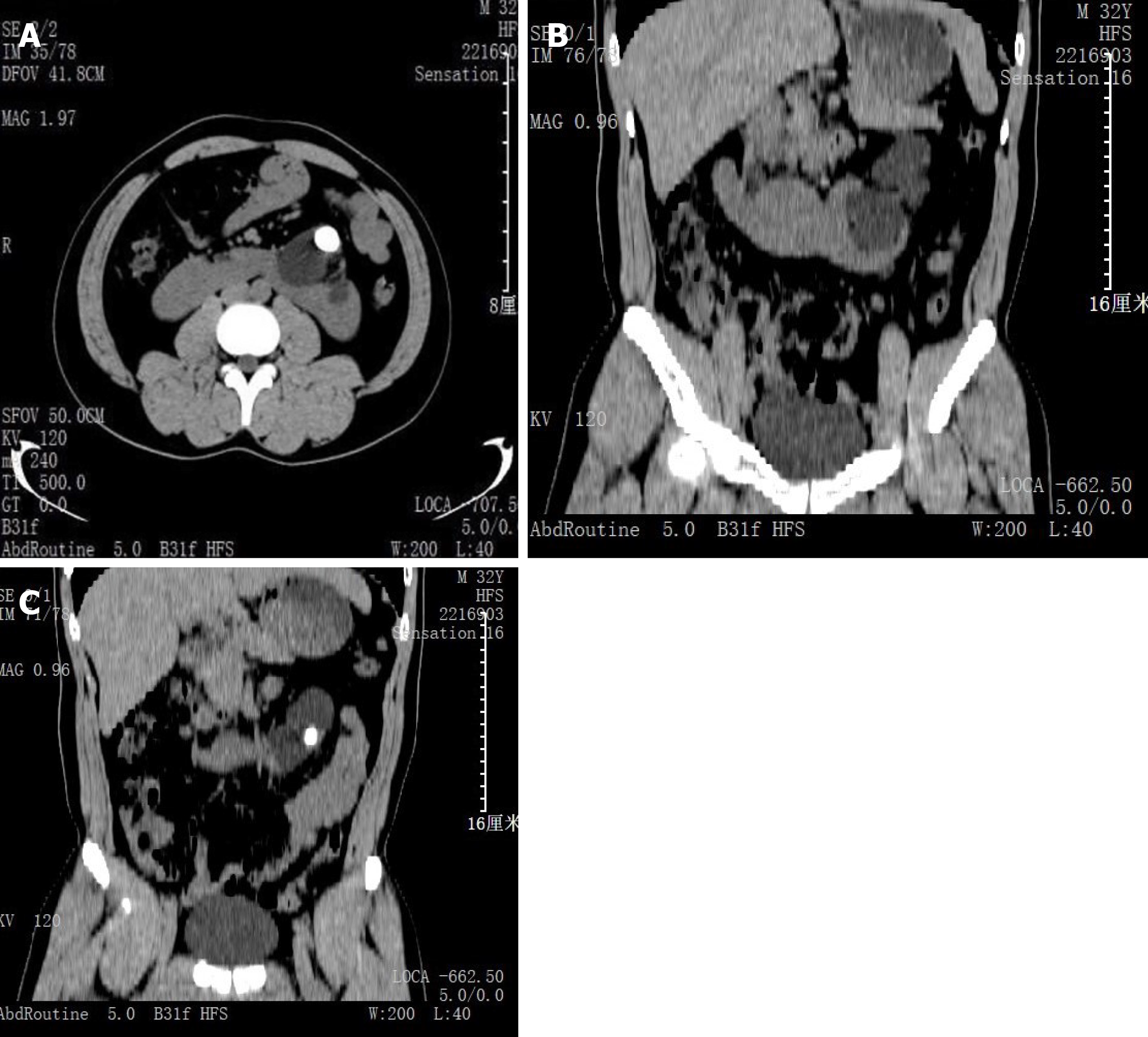

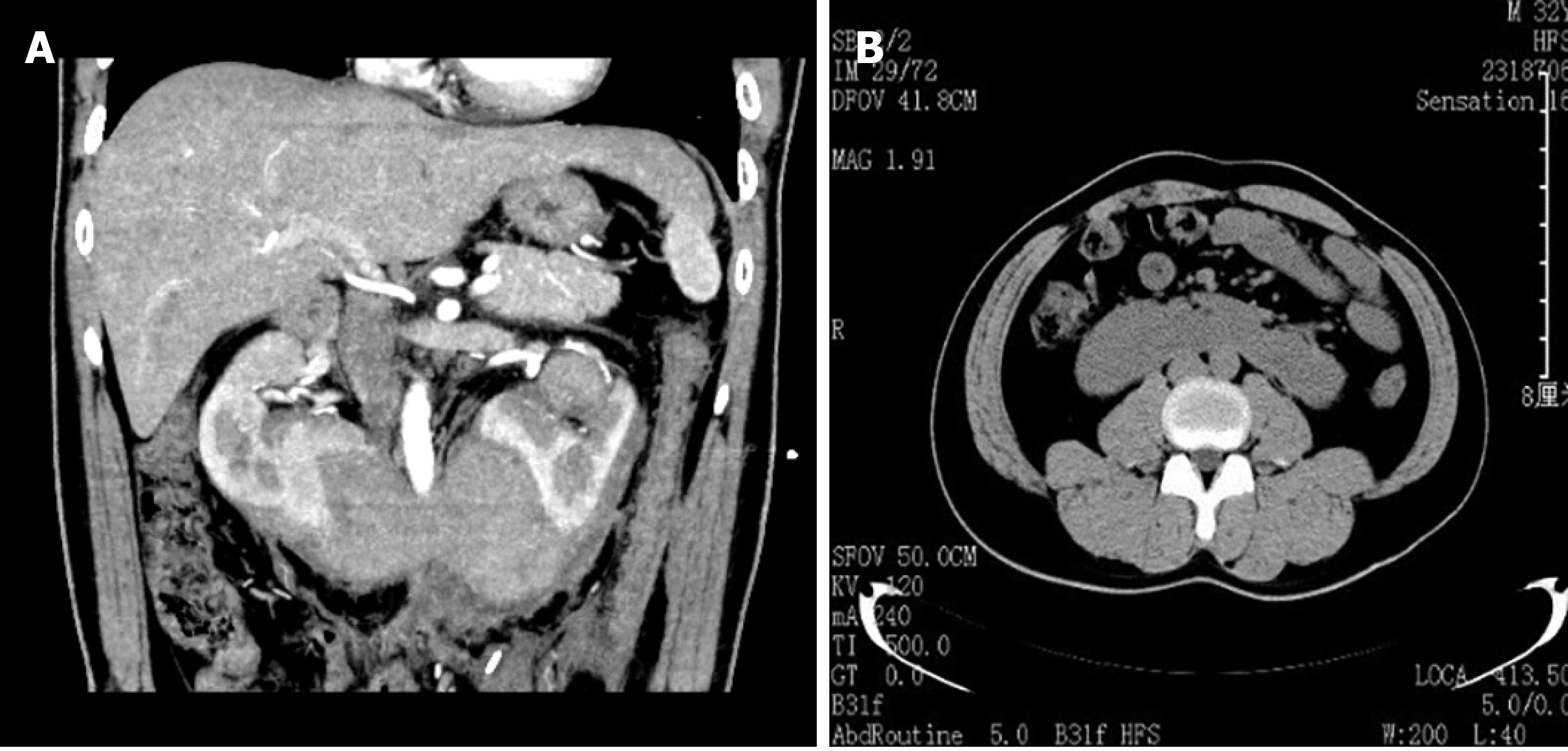

Plain computed tomography (CT) scan of the urinary system showed a horseshoe kidney with left renal pelvis calculi; the largest being 2.0 cm (Figure 1A). Coronal CT slide displayed the lower pole fusion and location of the stone in the pelvis (Figure 1B, C). Flexible ureteroscopic (F-URS) lithotripsy was performed under lumbar anesthesia. During the operation, the upper ureteral segment was found to be severely twisted and narrowed, making it impossible to pass through the flexible ureteroscope; therefore, PCNL was used instead. With the patient in the prone position, the operation tract of F14 was successfully established by puncturing in the 11th subcostal ultrasonography at the left posterior axillary line. An F8/9.8 ureteroscope was placed along the tract, and a golden stone measuring about 2.5 cm × 2.0 cm was seen at the ureteropelvic junction. The stone was smashed with a holmium laser, and the F6 double J stent tube was indwelled. There was a small amount of blood loss during the operation. The lithotripsy procedure lasted 30 min without placing the nephrostomy tube. The patient presented no significant postoperative gross hematuria or discomfort such as backache. The kidney, ureters and bladder (KUB) re-examination 1 d after the operation showed no residual stones (Figure 2). The catheter was removed 3 d after the operation and the patient was discharged from the hospital uneventfully. On day 6 after surgery, the patient complained of nausea and vomiting with right low back pain with no obvious gross hematuria. Plain abdominal CT scan revealed a subcapsular and perirenal hematoma in both kidneys (Figure 3A), and the patient was readmitted to hospital. Routine blood examination showed white blood cells (WBCs) 21 × 109/L, hemoglobin 7.9 g/dL, and creatinine 273.5 μmol/L. The subcapsular and perirenal hematocele of both kidneys was considered to be associated with infection and renal insufficiency. On day 8 after lithotripsy, ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage of perirenal effusion were performed, and a 10F drainage tube was indwelled, draining out 100 mL bloody fluid. About 50 mL blood fluid was drained every day for four consecutive days, during which, the patient ran a fever (38.2°C), for which anti-infective treatment was prescribed. Routine blood examination on day 7 after drainage showed WBCs 9.86 × 109/L, hemoglobin 6.9 g/dL and creatinine 211.7 μmol/L, and 1.5 U blood was transfused. On day 9 after drainage, the temperature became normal, and routine blood examination showed WBCs 12.63 × 109/L, hemoglobin 9 g/dL and cretinine 131.2 μmol/L. After the body temperature stabilized for 3 d, the patient received low-pressure injection of urokinase 100000 U (in 10-mL normal saline via the perirenal drainage tube). On day 22, the routine blood indexes and the renal function became normal. CT re-examination 3 mo after lithotripsy showed that the subcapsular and perinephric hematoma and exudates of both kidneys were significantly absorbed as compared with those before (Figure 3B).

No special personal and family history.

On day 6 after surgery, the patient complained of nausea and vomiting with right low back pain with no obvious gross hematuria.

Routien blood examination showed WBCs 21 × 109/L, hemoglobin 7.9 g/ dL and creatinine 273.5 μmol/L.

Abdominal CT scan revealed a subcapsular and perirenal hematoma in both kidneys.

The subcapsular and perirenal hematoceles of both kidneys were considered to be associated with infection and renal insufficiency. Ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage of perirenal effusion should be performed.

The subcapsular and perirenal hematoceles of both kidneys were considered to be associated with infection and renal insufficiency.

On day 8 after lithotripsy, ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage of perirenal effusion were performed, and a 10F drainage tube was indwelled, draining out 100 mL bloody fluid. About 50 mL blood fluid was drained every day for four consecutive days, during which the patient ran a fever (38.2°C), for which anti-infective treatment was prescribed. Routine blood examination on day 7 after drainage showed WBCs 9.86 × 109/L, hemoglobin 6.9 g/dL and creatinine 211.7 μmol/L, and 1.5 U blood was transfused. On day 9 after drainage, the temperature became normal, and routine blood examination showed WBCs 12.63 × 109/L, hemoglobin 9 g/dL and creatinine 131.2 μmol/L. After the body temperature stabilized for 3 d, the patient received low-pressure injection of urokinase 100 000 U (in 10-mL normal saline via the perirenal drainage tube).

On day 22, the routine blood indexes and the renal function became normal. CT re-examination 3 mo after lithotripsy showed that the subcapsular and perinephric hematoma and exudates of both kidneys were significantly absorbed as compared with those before.

Treatment strategies for horseshoe kidney stones include extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy[2], laparoscopic lithotripsy[3], F-URS lithotripsy[4], and percutaneous nephrolithotripsy[5,6].

Given the high recurrence rate of horseshoe kidney stones, F-URS flexible ureteroscopy with holmium laser has become the treatment of choice for horseshoe kidney stones due to its advantages of minimal invasiveness and repeatability[7]. In this case, we initially used F-URS lithotripsy. However, as two attempts of ureteroscopy (F8-9.8) and F-URS lithotripsy (F8) failed to pass through the ureteral stricture, we used PCNL instead.PCNL is commonly used to treat kidney stones or upper ureteral calculi. However, the anatomy of the horseshoe kidney and its surrounding organs is different from that in normal patients, and the special anatomy of the renal pelvis and calyces makes it difficult to identify percutaneous nephrolithotomy in the process of puncture and endoscopy, which increases the complication risk of horseshoe kidney PCNL[8]. In this case, bilateral renal subcapsular hemorrhage has its own particularity. Firstly, the bilateral kidneys and isthmus are connected as a whole; once exudation and subcapsular hemorrhage occur, the hematoma area is three times as large as the normal kidney, making the condition even worse. Secondly, the increase in the overall area of the horseshoe kidney makes the capsule loose compared with the ordinary kidney. Once subcapsular hemorrhage occurs, it is not easy to form compression and hemostasis, resulting in more serious bleeding. Mild urine extravasation can be absorbed by itself. Mass urinary exosmosis can lead to a chain of symptoms such as low back pain, infection and anemia, accompanied by infection and even rare spontaneous isthmus rupture[2].

To the best of our knowledge, there is no study reporting the formation of bilateral hematoma following tubeless PCNL for unilateral horseshoe kidney calculi. In treating this patient, we learned some lessons. The calculi of this patient were located at the ureteropelvic junction, and the stone burden was medium. We tried ureteroscopy (F8-9.8) and PolyscopeTM flexible ureteroscopy (F8) but were unable to pass through the stenotic ureter. Failure of flexible ureteroscopy was attributed to ureteric stenosis. However, studies have shown that horseshoe kidney is associated with a significant rate of ureteropelvic obstruction. At this time, especially for the horseshoe kidney, the double-J (DJ) stent should be placed 2–4 wk in advance to facilitate the passage of the endoscope and the outflow of irrigation while the stones are being crushed. If the F6/7.5 ureteroscope or visible precise puncture system (F4.8) is replaced, the ratio of endoscope-sheath diameter (RESD) can be reduced, thus increasing the outflow of the irrigative fluid and reducing the intrarenal pressure, which could effectively reduce the risk of renal capsule hemorrhage. Our colleagues[9] reported that RESD should be kept below 0.75 to maintain a low intrapelvic pressure and an acceptable flow rate during endoscope lasertripsy. In the present case, we evaluated the effect of lithotripsy by KUB, not by CT. In our opinion, it is necessary to evaluate postoperative perirenal exudation and capsule hemorrhage routinely by CT scan to prevent possible complications. As there was no residual stone during the operation, we did not place the nephrostomy tube in this patient in view of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS). Some recent publications[10,11] indicate that tubeless PCNL is an available and safe option in carefully evaluated and selected patients. Our patient had a horseshoe kidney and his renal function was lower than that in ordinary patients. As the cortex was thin and had lost the systolic function, the fistula was not easy to close, which may have aggravated urinary extravasation. Therefore, for complex cases such as horseshoe kidney stones after PCNL, safety is a precondition of ERAS. The nephrostomy tube and DJ stent should be routinely placed to reduce urinary extravasation and subcapsular bleeding, even in patients with a high stone-free rate and no need for a secondary procedure. The urethral catheter was removed on day 3 after lithotripsy. The hypertension caused by the bladder fullness may lead to vesicoureteric reflux, which may also be the probable cause of elevation of the bilateral intrarenal pressure, which may aggravate subcapsular hemorrhage. Therefore, we believe that the time of postoperative catheterization in such special cases can be appropriately prolonged. Timely injection of urokinase, a protease extracted from fresh human urine, via the perirenal drainage tube can dissolve and drain the perirenal blood clots and should preferably be performed at the time when the renal hematoma is no longer enlarged and body temperature returns normal for 3 d.

| 1. | Etemadian M, Maghsoudi R, Abdollahpour V, Amjadi M. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in horseshoe kidney: our 5-year experience. Urol J. 2013;10:856-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Blackburne AT, Rivera ME, Gettman MT, Patterson DE, Krambeck AE. Endoscopic Management of Urolithiasis in the Horseshoe Kidney. Urology. 2016;90:45-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Breish MO, Sarnaik S, Sriprasad S, Hamdoon M. Laparoscopic Nephrolithotomy in a Horseshoe Kidney. Cureus. 2020;12:e7099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Andreoni C, Portis AJ, Clayman RV. Retrograde renal pelvic access sheath to facilitate flexible ureteroscopic lithotripsy for the treatment of urolithiasis in a horseshoe kidney. J Urol. 2000;164:1290-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Symons SJ, Ramachandran A, Kurien A, Baiysha R, Desai MR. Urolithiasis in the horseshoe kidney: a single-centre experience. BJU Int. 2008;102:1676-1680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Purkait B, Sankhwar SN, Kumar M, Patodia M, Bansal A, Bhaskar V. Do Outcomes of Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy in Horseshoe Kidney in Children Differ from Adults? J Endourol. 2016;30:497-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vicentini FC, Mazzucchi E, Gökçe Mİ, Sofer M, Tanidir Y, Sener TE, de Souza Melo PA, Eisner B, Batter TH, Chi T, Armas-Phan M, Scoffone CM, Cracco CM, Perez BOM, Angerri O, Emiliani E, Maugeri O, Stern K, Batagello CA, Monga M. Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy in Horseshoe Kidneys: Results of a Multicentric Study. J Endourol. 2021;35:979-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen H, Chen G, Pan Y, Zhu Y, Xiong C, Chen H, Yang Z. No Wound for Stones <2 cm in Horseshoe Kidney: A Systematic Review of Comparative Studies. Urol Int. 2019;103:249-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fang L, Xie G, Zheng Z, Liu W, Zhu J, Huang T, Lu Y, Cheng Y. The Effect of Ratio of Endoscope-Sheath Diameter on Intrapelvic Pressure During Flexible Ureteroscopic Lasertripsy. J Endourol. 2019;33:132-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee JY, Jeh SU, Kim MD, Kang DH, Kwon JK, Ham WS, Choi YD, Cho KS. Intraoperative and postoperative feasibility and safety of total tubeless, tubeless, small-bore tube, and standard percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials. BMC Urol. 2017;17:48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Xun Y, Wang Q, Hu H, Lu Y, Zhang J, Qin B, Geng Y, Wang S. Tubeless vs standard percutaneous nephrolithotomy: an update meta-analysis. BMC Urol. 2017;17:102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cassell III AK S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Xing YX