Published online Oct 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.9295

Peer-review started: June 6, 2021

First decision: June 25, 2021

Revised: July 5, 2021

Accepted: August 27, 2021

Article in press: August 27, 2021

Published online: October 26, 2021

Processing time: 137 Days and 3 Hours

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is the leading cause of acute liver failure in the United States. DILI is mainly caused by painkillers and fever reducers, and it is often characterized by the type of hepatic injury (hepatocellular or cholestatic). This report presents a case of fenofibrate-induced severe jaundice in a 65-year-old Korean male with no prior history of liver disease. We offer a strategy for patients who present signs of severe liver injury with jaundice and high elevations in serum transaminases.

A 65-year-old male visited the gastroenterology outpatient clinic of a tertiary hospital due to increased levels of liver enzyme and total bilirubin which were incidentally detected through a preoperative screening test. Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography showed no biliary obstruction or non-specific findings in the liver. Liver biopsy was performed and the patient was finally diagnosed with acute cholestatic hepatitis. Following the biopsy, steroid therapy was initiated and after 3 wk of treatment, the total bilirubin level was reduced to 7.22 mg/dL.

In patients with hyperlipidemia, treatment including fenofibric acid induces rare complications such as severe jaundice and acute cholestatic hepatitis, warranting clinical attention.

Core Tip: In patients with hyperlipidemia, treatment including fenofibric acid causes rare complications such as severe jaundice and acute cholestatic hepatitis, which requires clinical attention.

- Citation: Lee HY, Lee AR, Yoo JJ, Chin S, Kim SG, Kim YS. Biopsy-confirmed fenofibrate-induced severe jaundice: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(30): 9295-9301

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i30/9295.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.9295

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) accounts for approximately 10% of all cases of acute hepatitis, and it is the most common cause of acute liver failure in the United States[1]. DILI is usually caused by medications, herbal medications, ethanol and dietary supplements. In particular, painkillers and fever reducers taken in doses more than recommended are the main causes of DILI[2]. DILI is often characterized by the type of hepatic injury, which is divided into hepatocellular or cholestatic injury[3]. Hepatocellular injury leads to increased serum aminotransferases in comparison to alkaline phosphatase. Cholestatic liver injury causes elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels compared to serum aminotransferases. DILI cholestasis is defined as an increase in ALP > 2 × upper limit of normal (ULN) and an alanine aminotransferase (ALT)-to-ALP ratio less than 2[4].

This report presents a case of fenofibrate-induced severe jaundice in a 65-year-old Korean male patient with no prior history of liver disease. We discuss our investigative and management approach, and present a review of prior cases. A strategy for patients with signs of severe liver injury accompanied by jaundice and elevation in serum transaminases is also suggested.

A 65-year-old male with severe jaundice visited the outpatient referral university hospital.

A 65-year-old male was referred to a gastroenterology outpatient clinic of a tertiary hospital due to jaundice and increased levels of liver enzyme which were incidentally detected during a preoperative screening at a local clinic.

In early February 2021, the patient was treated with 135 mg of fenofibric acid due to hyperlipidemia. In mid-February 2021, he was incidentally diagnosed with a ureteric stone and was recommended to undergo surgery at a local hospital. In Korea, routine blood tests are performed prior to surgery in clinical practice that requires general anesthesia. The patient’s jaundice was discovered incidentally through a preoperative blood test. Prior to visiting the outpatient clinic, the patient experienced symptoms of mild itching and jaundice for 2 wk. Thus, we can assume that the patient developed jaundice during the first week of March, four weeks after the initiation of the drug.

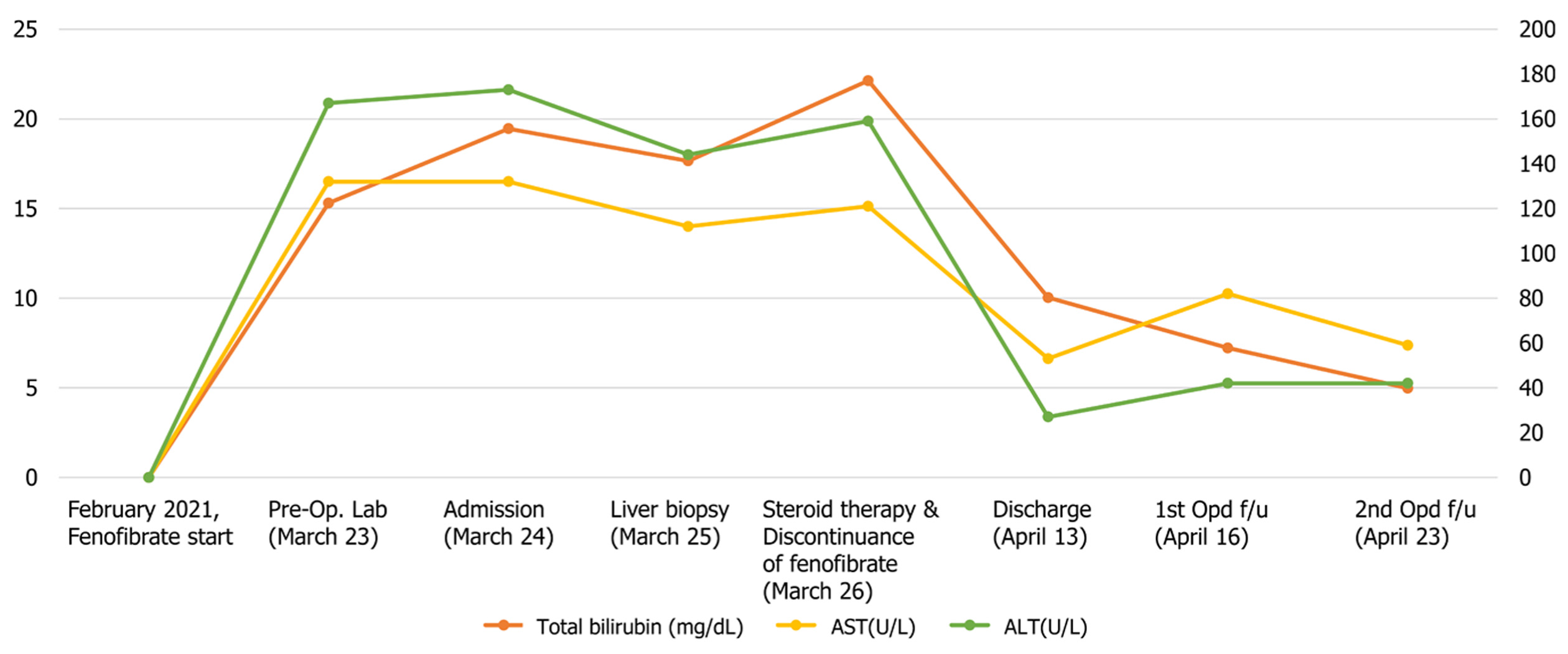

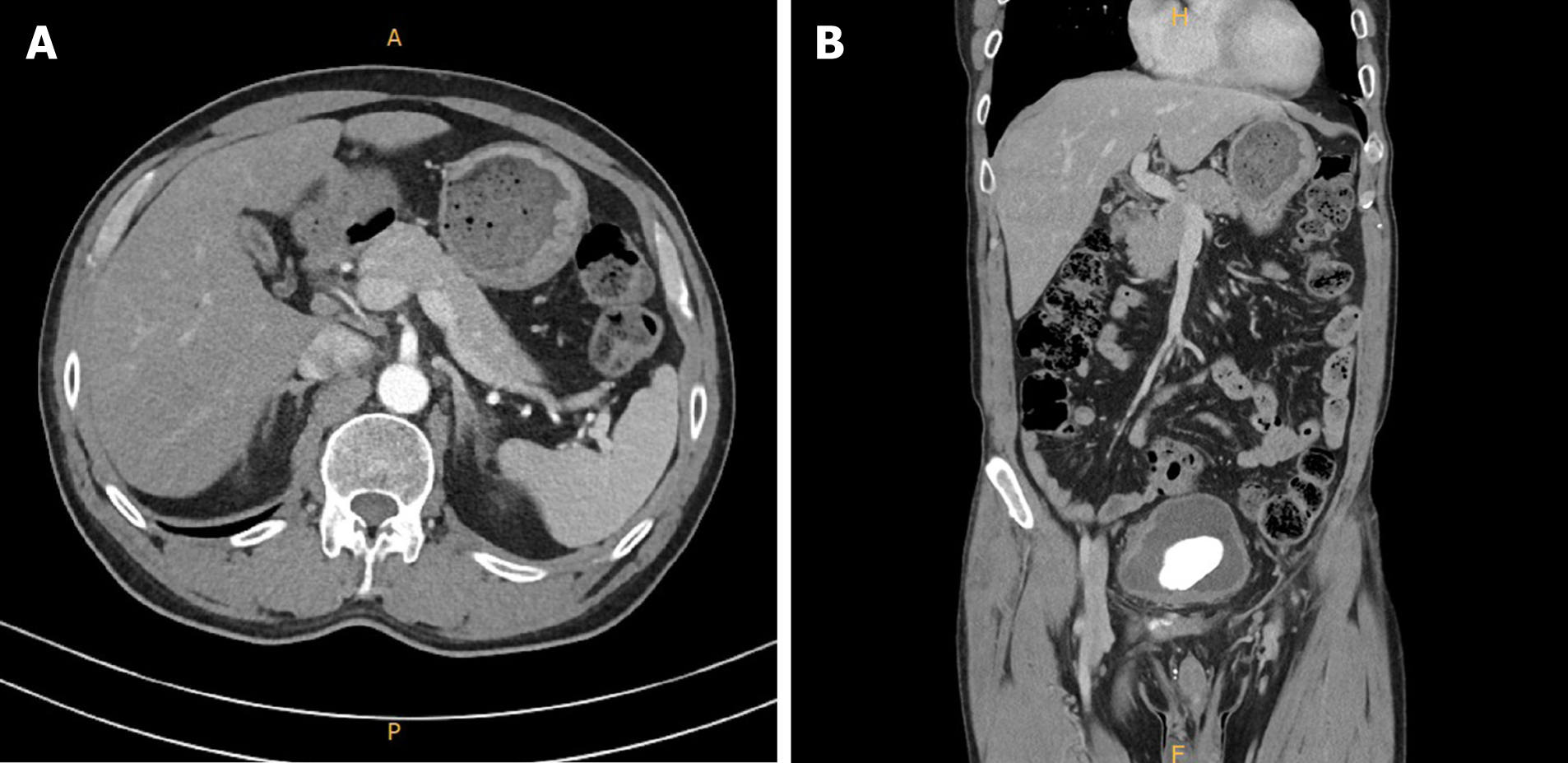

Laboratory tests showed increased ALT (172 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (133 U/L), ALP (1182 U/L), and total bilirubin (15.99 mg/dL) (Figure 1). Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (Figure 2) showed non-specific findings in the liver and no evidence of biliary obstruction.

The patient was a non-drinker and former smoker who quit smoking 10 years ago. He was diagnosed with hypertension 5 years ago and was administered with a daily dosage of amlodipine 5 mg and valsartan 160 mg.

There is no personal and family history.

At the time of admission, his height was 165.9 cm, weight 66.3kg, and BMI 24 kg/m2. His blood pressure was normal with a systolic blood pressure of 125 mmHg and a diastolic blood pressure of 80 mmHg. He had a normal body temperature (36.5°C) and normal heart rate (100 bpm). He also showed a normal breathing rate at 18 breaths per minute. He had a soft abdomen. He had a slight itching sensation and jaundice.

Before visiting our hospital, the patient underwent blood tests at a local hospital. His AST, ALT, and ALP counts were 133 U/L, 172 U/L, and 1182 U/L, respectively. Initial PT and aPTT values were 12.4 s and 34.2 s, respectively. The total bilirubin level was 15.99 mg/dL. However, after admission, the AST, ALT and ALP counts were reduced to 120 U/L, 144 U/L, and 366 U/L, respectively. Over the course of several days after admission, the patient’s serum bilirubin level rose up to a maximum of 22.13 mg/dL (Figure 1). His prothrombin time international normalized ratio (PT INR) was 0.92. All viral hepatitis markers (hepatitis B virus surface antigen, immunoglobulin M antibody to hepatitis A, hepatitis C antibody, immunoglobulin M antibody to hepatitis E virus) were negative. Serum ferritin and ceruloplasmin were in the normal range at 128 ng/mL and 36.9 mg/dL, respectively. All of the following autoantibody tests showed negative results: anti-nuclear antibody, anti-mitochondrial antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-liver/kidney microsomal antibodies type 1. Factor V levels were not determined.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography revealed a few small cysts in both liver lobes. The patient’s gall bladder was not well expanded and the wall showed diffuse thickening, without bile duct obstruction (Figure 2).

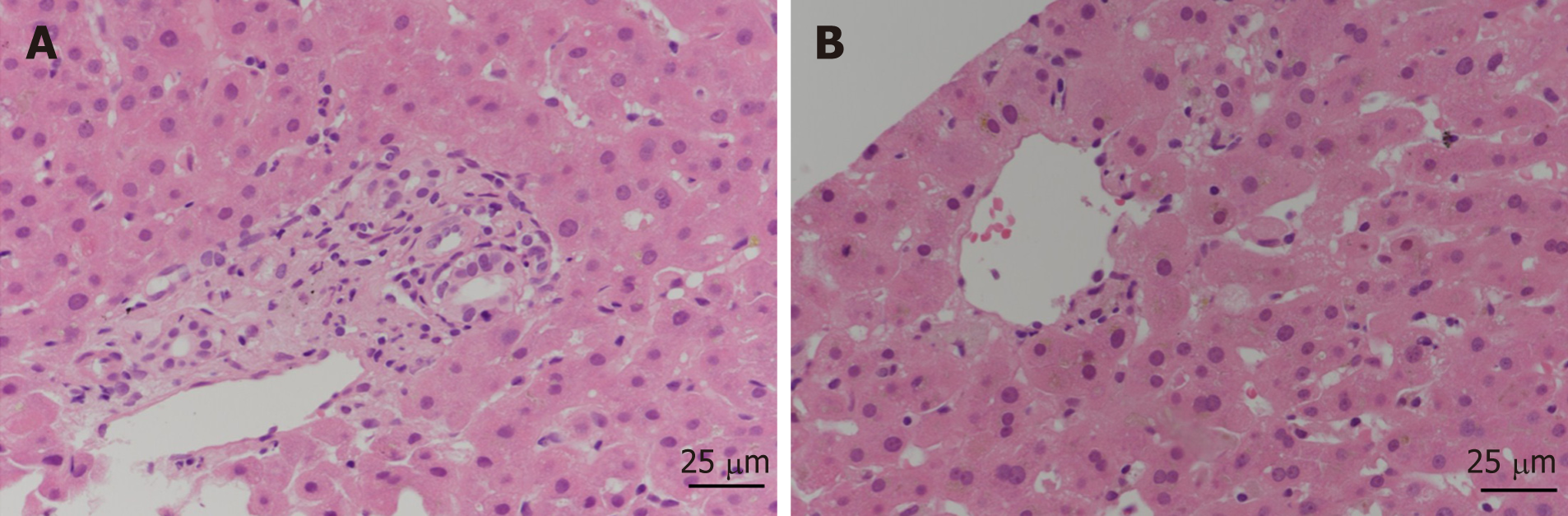

A liver biopsy to establish the cause of jaundice was performed. Liver biopsy showed acute cholestatic hepatitis consistent with toxic hepatitis (Figure 3). The Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method score was 6 (time to onset from the beginning of the drug/herb: 2 points; course of ALP after cessation of the drug/herb: 2 points; risk factors such as age: 1 point; search for alternative causes: 1 point) which indicates that fenofibrate is the probable cause of DILI. Thus, we diagnosed the patient with severe DILI due to fenofibrate.

After the biopsy, the patient was treated empirically for DILI with prednisolone 40 mg daily for one week. The dose of prednisolone was subsequently rapidly reduced.

Steroid therapy was initiated the day after liver biopsy. At the time of discharge, the AST and ALT levels of the patient were reduced to 53 U/L and 27 U/L, respectively. The total bilirubin level decreased to 10.03 mg/dL. The patient was discharged after 3 wk of inpatient treatment. After discontinuation of fibrate treatment, jaundice improved rapidly and the patient is currently being observed in the outpatient clinic (Figure 1).

Fenofibrate is a fibric acid derivative commonly used to reduce cholesterol and triglycerides[5,6]. The most common adverse effects of fibrates include gastrointestinal upset, nausea, headache and muscle cramps and rash, which are mostly mild and generally transient symptoms[5,7-9]. Despite its widespread use, fenofibrate rarely causes clinically significant hepatotoxicity[5,10-12]. Mild and transient elevations in serum aminotransferase develop in 5%-10% of patients[6]. DILI associated with fenofibrate occurs very rarely, in only 0.6% of patients[6]. Although most fenofibrate-induced liver injuries are self-limited, serious DILIs associated with fenofibrate can occur, if discontinuation of drug is delayed.

The characteristics of fibrate-induced hepatitis are not well known due to its rare occurrence. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 11 cases are presented in Table 1. Fenofibrate-induced liver injury appears to afflict older men. Seven of the 11 patients were male (63.6%) and the median age was 54 years, with an age range of 37-74 years[6,7,13,14]. BMI was reported in 7 patients. All patients reported BMI values which were either overweight [body mass index (BMI) 25–30 kg/m2] or obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2)[6]. Four out of the 11 total patients had diabetes mellitus. The onset of injury was variable. Latency was short (2 d to 8 wk) in 7 patients [7,8,13], and prolonged up to 2 years (18 wk-2 years) in the other 4 patients[6,14].

| Ref. | Demographic and clinical characteristics | Course of illness | Initial values | ||||||||

| Location | Sex | Age, yr | Daily dose (mg) | Symptoms | Latency | Outcome | ALT(U/L) | ALP(U/L) | Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | INR | |

| Present case | South Korea | M | 65 | 135 mg | Jaundice, pruritis | 6 wk | Recovery, 3 wk | 172 | 1182 | 15.99 | 0.92 |

| Ma et al[13], 2019 | China | M | 65 | 200 mg | Epigastric discomfort, nausea,fatigue | 2 d | Recovery, 2 wk | 1136.7 | 279.7 | 1.91 | NA |

| Dohmen et al[7], 2005 | Japan | F | 66 | 150 mg | Fever, anorexia, hypochondrial discomfort | 11 d | Recovery, 2 wk | 216 | 537 | 1.8 | NA |

| Rigal et al[14], 1989 | France | F | 74 | 200 mg | Jaundice | 2 yr | Recovery, 2 mo | 1430 | 315 | 4.6 | NA |

| Ho et al[8], 2004 | Taiwan | M | 61 | 300 mg | Jaundice, dark urine, fatigue | 2 wk | Recovery, 2 mo | 249 | 259 | 9.3 | NA |

| Case 1 (Ahmad et al[6], 2017) | Caucasian | M | 43 | 145 mg | Jaundice, dark urine, pale stool, pruritis | 6 wk | Recovery | 533 | 440 | 20.6 | 1.04 |

| Case 2 (poor prognosis) (Ahmad et al[6], 2017) | Caucasian | M | 61 | 48 mg | Jaundice, rash, pruritis | 8 wk | Death (renal failure) at 26 mo | 83 | 518 | 4.7 | 1.40 |

| Case 3 (Ahmad et al[6], 2017) | Hispanic | F | 37 | 160 mg | Jaundice, nausea, fatigue, myalgia, abdo pain | 5 wk | Recovery | 332 | 344 | 8.4 | 0.80 |

| Case 4 (Ahmad et al[6], 2017) | Caucasian | M | 43 | 145 mg | Jaundice, nausea, fatigue, dark urine, pale stool, fever, pruritis | 7 wk | Unknown | 100 | 218 | 5.9 | 1.00 |

| Case 5 (poor prognosis) (Ahmad et al[6], 2017) Jaward et al. 2017[6] | Caucasian | M | 41 | 160 mg | Jaundice, abdominal pain, nausea | 40 wk | Liver Transplant, at 8 mo | 78 | 195 | 8.0 | 4.3 |

| Case 6 (Ahmad et al[6], 2017) | Hispanic | M | 54 | 134 mg | Fatigue | 56 wk | Recovery | 584 | 106 | 0.5 | NA |

| Case 7 (Ahmad et al[6], 2017) | Caucasian | F | 44 | 48 mg | Jaundice, dark urine, fatigue | 18 wk | Recovery | 1197 | 79 | 5.1 | 1.00 |

Biochemically, the initial pattern of liver injury (based on the R ratio) was variable but patients who manifested initial cholestatic patterns of liver injury showed severe clinical outcomes. In particular, the clinical prognosis was poor when the initial prolongation of PT INR was high. Both patients with severe injury and PT prolongation were characterized by delayed drug discontinuation. In the case of death, PT INR was 1.4 and in the case of liver transplantation 4.3. Data from published cases reflect an average elevation of ALT of 13 × ULN (539.88), ALP 3 × ULN (373), and total bilirubin of 6 × ULN (7.23).

Patients with high levels of serum total bilirubin at the time of admission were hospitalized longer and showed delayed recovery. Of the 4 cases with prolonged hospital stay or slow recovery, one recovered in a relatively short time, and all of them showed acute hepatitis on biopsy. In this case, the total bilirubin level rose to 22.13 mg/dL, but recovered within 3 wk, and histological findings showed acute hepatitis.

The common pathological findings of toxic hepatitis include necrosis and cholestasis, although these are not specific to toxic hepatitis. Five of the 11 cases reviewed underwent liver biopsy. Liver biopsy showed diverse patterns of injury, based on published literature, with most of the cases showing cholestasis. The clinical prognosis was worse in the case of chronic cholestasis in the liver biopsy than in the case of acute cholestasis. Chronic cholestasis was associated with duct injury that was characterized by reactive epithelial changes rather than direct inflammation[6].

While the majority of DILIs resolve with prompt discontinuation of the offending drug, DILIs can worsen and progress to liver failures that require transplantation or result in death, particularly if drug withdrawal is delayed. Nine of the 11 cases with acute hepatotoxicity fully recovered and 2 developed a severe clinical course. One underwent liver transplantation at 8 mo and the other eventually died of renal failure at 26 mo. Both severe cases had delayed cessation of fenofibrate therapy, which resulted in chronic progressive cholestatic liver injury[6]. Reported cases of fenofibrate-induced hepatitis appear to be idiosyncratic. The mechanism of idiosyncratic DILI remains unresolved. However, sufficient evidence exists that most idiosyncratic cases are mediated by adaptive immune systems which depend on stimulation of the innate immune system, although the triggering factors are unknown. One of the patients receiving the minimal recommended dose (48 mg) died.

Possible risk factors for severe hepatic injury may include older age, prolonged PT, cholestatic pattern of initial liver injury, multiple gallstones and history of cholecystectomy. In patients with these risk factors, delayed drug discontinuation can lead to poor outcomes. However, well-controlled studies are needed to corroborate these findings.

High BMI is frequently reported in patients with fibrate-induced liver injury. Hyperlipidemia is one of the metabolic syndrome items, and such patients are often accompanied by obesity. In fact, in most of the previous case reports of fibrate-induced jaundice, the majority of patients were obese with a BMI of 25 mg/m2 or higher. However, it is not yet known whether high BMI is a simple bias or a real risk factor. Further research is needed to determine whether the two factors have a simple association or a temporal causal relationship. In our case as well, the patient's BMI was 24, demonstrating that fibrate-induced jaundice can sufficiently occur even in patients with low BMI.

Fenofibrate is widely prescribed for patients with hypertriglycemia to decrease the risk of cardiovascular diseases. Fenofibrate-induced hepatitis is a rare type of DILI. However, fenofibrate–induced DILI can be severe and prolonged with the potential for chronicity due to delayed discontinuation. Older males with high BMI, prolonged PT, cholestatic pattern of liver injury, and history of cholestatic hepatobiliary disease are more likely to develop severe liver injury associated with jaundice and high elevations in serum transaminases.

Routine liver biochemistry monitoring is recommended at least 2 wk after initial fenofibrate ingestion followed by regular monitoring every 3 mo within the first 1 to 2 years of therapy. Discontinuation is recommended if liver enzymes persist at levels above 3 times the ULN or if jaundice is detected. Clinicians need to discontinue treatment in patients with jaundice and highly elevated liver enzymes during fenofibrate therapy.

| 1. | Ghabril M, Chalasani N, Björnsson E. Drug-induced liver injury: a clinical update. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:222-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kumar N, Surani S, Udeani G, Mathew S, John S, Sajan S, Mishra J. Drug-induced liver injury and prospect of cytokine based therapy; A focus on IL-2 based therapies. Life Sci. 2021;278:119544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yu YC, Mao YM, Chen CW, Chen JJ, Chen J, Cong WM, Ding Y, Duan ZP, Fu QC, Guo XY, Hu P, Hu XQ, Jia JD, Lai RT, Li DL, Liu YX, Lu LG, Ma SW, Ma X, Nan YM, Ren H, Shen T, Wang H, Wang JY, Wang TL, Wang XJ, Wei L, Xie Q, Xie W, Yang CQ, Yang DL, Yu YY, Zeng MD, Zhang L, Zhao XY, Zhuang H; Drug-induced Liver Injury (DILI) Study Group; Chinese Society of Hepatology (CSH); Chinese Medical Association (CMA). CSH guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of drug-induced liver injury. Hepatol Int. 2017;11:221-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Katarey D, Verma S. Drug-induced liver injury. Clin Med (Lond). 2016;16:s104-s109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bhardwaj SS, Chalasani N. Lipid-lowering agents that cause drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Clin Liver Dis. 2007;11:597-613, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ahmad J, Odin JA, Hayashi PH, Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Barnhart H, Cirulli ET, Kleiner DE, Hoofnagle JH. Identification and Characterization of Fenofibrate-Induced Liver Injury. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:3596-3604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dohmen K, Wen CY, Nagaoka S, Yano K, Abiru S, Ueki T, Komori A, Daikoku M, Yatsuhashi H, Ishibashi H. Fenofibrate-induced liver injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7702-7703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ho CY, Kuo TH, Chen TS, Tsay SH, Chang FY, Lee SD. Fenofibrate-induced acute cholestatic hepatitis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2004;67:245-247. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kiskac M, Zorlu M, Cakirca M, Karatoprak C, Peru C, Erkoc R, Yavuz E. A case of rhabdomyolysis complicated with acute renal failure after resumption of fenofibrate therapy: a first report. Indian J Pharmacol. 2013;45:305-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Parra JL, Reddy KR. Hepatotoxicity of hypolipidemic drugs. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:415-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chitturi S, George J. Hepatotoxicity of commonly used drugs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antihypertensives, antidiabetic agents, anticonvulsants, lipid-lowering agents, psychotropic drugs. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22:169-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Keech A, Simes RJ, Barter P, Best J, Scott R, Taskinen MR, Forder P, Pillai A, Davis T, Glasziou P, Drury P, Kesäniemi YA, Sullivan D, Hunt D, Colman P, d'Emden M, Whiting M, Ehnholm C, Laakso M; FIELD study investigators. Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1849-1861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2540] [Cited by in RCA: 2269] [Article Influence: 108.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ma S, Liu S, Wang Q, Chen L, Yang P, Sun H. Fenofibrate-induced hepatotoxicity: A case with a special feature that is different from those in the LiverTox database. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;45:204-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rigal J, Furet Y, Autret E, Breteau M. [Severe mixed hepatitis caused by fenofibrate? Rev Med Interne. 1989;10:65-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Malnick SDH S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL