Published online Oct 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.9205

Peer-review started: May 12, 2021

First decision: June 15, 2021

Revised: June 24, 2021

Accepted: August 30, 2021

Article in press: August 30, 2021

Published online: October 26, 2021

Processing time: 161 Days and 23.1 Hours

Dizziness is a common symptom in adults and usually due to peripheral causes affecting semicircular canal function or central causes affecting the pons, medulla, or cerebellum. Arrhythmia is a recognized cause of dizziness in people with structural or ischemic heart disease. We report a case of exercise-induced transient ventricular tachycardia and dizziness in a man with no evidence of organic heart disease.

A 42-year-old man presented with a 6 mo history of transient exercise-induced dizziness and prodromal palpitations. The patient was otherwise asymptomatic. Physical examination, otoscopy, vestibular tests, cerebellar tests, laboratory investigations, and imaging investigations were all unremarkable. Twenty-four hour Holter monitoring revealed four episodes of transient ventricular tachycardia during exercise. The patient was started on metoprolol and subsequently underwent radiofrequency catheter ablation. The patient reported a full recovery and no dizziness during daily activities. These results were maintained at the 6 mo follow-up.

Ventricular tachycardia is an uncommon but potentially serious cause of dizziness. The outcome of this case illustrates the benefits of careful clinical examination and communication with specialized centers. High clinical suspicion of arrhythmia in a patient with dizziness merits consultation with a cardiologist and referral to a specialized center to ensure timely diagnosis and treatment.

Core Tip: Ventricular tachycardiais an uncommon but potentially serious cause of dizziness. High clinical suspicion of arrhythmia in a patient with dizziness merits consultation with a cardiologist and referral to a specialized center to ensure timely diagnosis and treatment.

- Citation: Gao LL, Wu CH. Transient ventricular arrhythmia as a rare cause of dizziness during exercise: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(30): 9205-9210

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i30/9205.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.9205

Dizziness is a general term for a sense of disequilibrium that encompasses a range of symptoms such as light-headedness, vertigo (characterized by rotational dizziness), unsteadiness, presyncope (‘near-fainting’), and syncope. Dizziness affects around 20% of the adult population and is more common in women.Its prevalence increases with age[1,2]. Classically, dizziness is attributed to abnormal or unmatched signals from sensory systems including the visual, somatosensory, and vestibular systems. The differential diagnosis of dizziness includes peripheral causes affecting the function of the semicircular canals in the inner ear and central causes affecting the pons, medulla, or cerebellum. The most common peripheral causes of dizziness include paroxysmal positional vertigo, vestibular neuritis, Menière’s disease, and otosclerosis, while frequent central causes include vestibular migraine, cerebrovascular disease, and meningioma affecting the cerebellopontine angle and posterior fossa[3]. Most cases of dizziness are diagnosed on the basis of the clinical history and a thorough physical examination (including full neurologic and cardiovascular assessments), although laboratory investigations (e.g., glucose and electrolyte measurements), computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, electronystagmography, the bithermal caloric test, and audiometry are useful in some patients[3].

Cardiac arrhythmia is a recognized cause of dizziness, presyncope, and syncope[4]. However, published data describing ventricular tachycardia (VT) as a cause of dizziness in patients without structural heart disease are limited. Here, we report a case of a 42-year-old man who experienced transient dizziness during exercise and was diagnosed with VT.

The patient reported experiencing transient symptoms of dizziness and prodromal palpitations while taking exercise.

On arrival at the neurology unit, the patient was conscious, calm, and asymptomatic, and he looked well. He described being pale and sweaty at the onset of the event, but the episode was not associated with any jerky body movements. The patient did not complain of chest pain, dyspnea, or visual changes. The patient was not taking any regular medications, and there was no medical history of note. He had smoked 40 cigarettes per day for 20 years but reported no use of other drugs or alcohol.

A 42-year-old man (Han nationality) was admitted to the neurology unit of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Traditional Chinese Medical University on February 13, 2018 with a 6 mo history of dizziness.

There was no history of syncope, epilepsy, or ill health and no family history of sudden cardiac death.

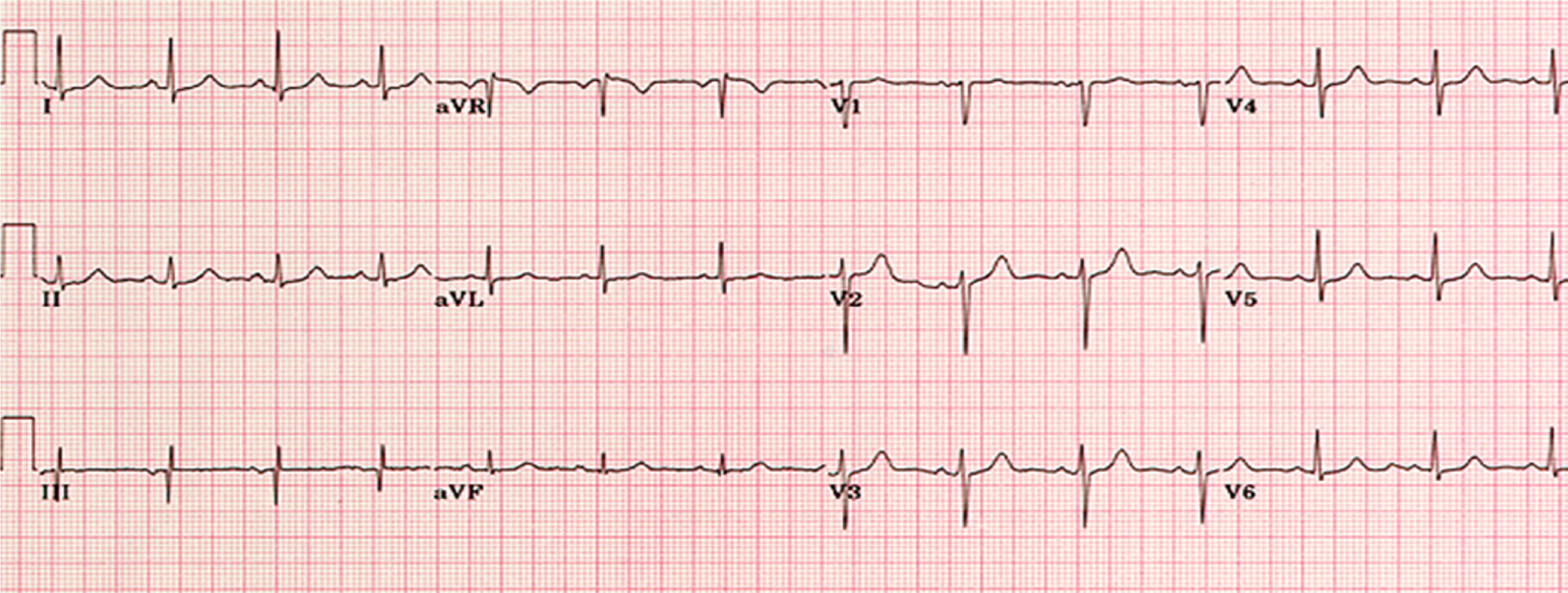

At admission, the patient’s blood pressure was 115/80 mmHg with no orthostatic hypotension, his pulse rate was 88 beats/min, and his respiration rate was 18 breaths/min. The physical examination was unremarkable. His presenting electrocardiogram demonstrated sinus rhythm with no ischemic changes (Figure 1).

Serum laboratory findings were normal.

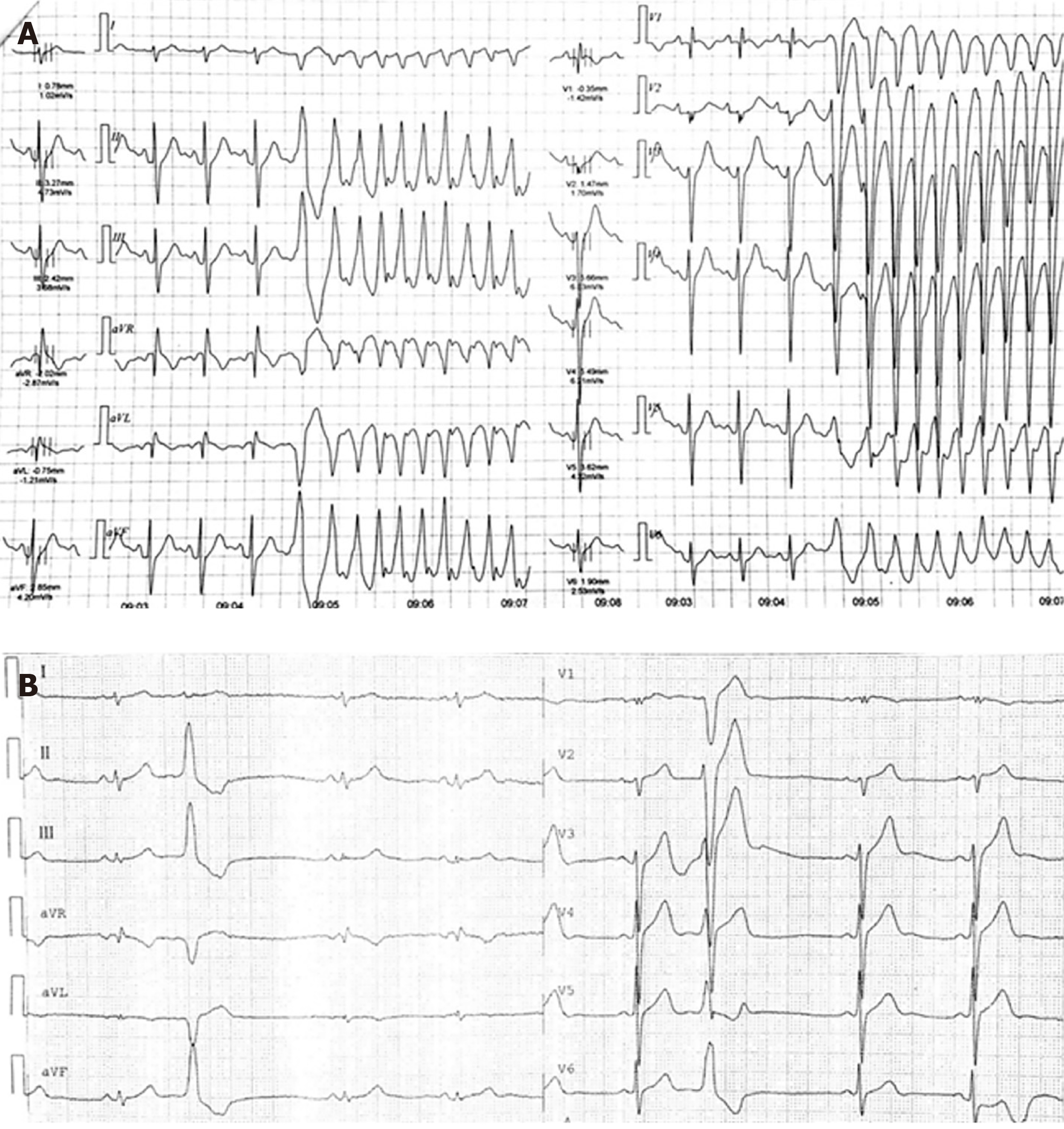

Computed tomography (Somatom Definition AS, Siemens, Germany), magnetic resonance imaging (Magnetom Skyra, Siemens, Germany), and magnetic resonance angiography of the brain did not reveal any abnormalities. Otoscopy, vestibular tests, and cerebellar tests returned normal results. He did not have spontaneous, positional, or movement induced nystagmus. Echocardiography (EPIQ7, Philips, Netherlands) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging did not demonstrate any abnormalities. However, 24 h Holter monitoring revealed four episodes of transient VT during exercise (Figure 2A).

Based on the results of 24 h Holter monitoring and the exclusion of other central or peripheral causes of dizziness, the patient was diagnosed with exercise-induced VT.

The patient was started on beta-blockers(metoprolol12.5 mg bd; Alyscon, United Kingdom) on February 16, 2018. He underwent radiofrequency catheter ablation on February 27, 2018. One month after admission, the patient reported that the symptoms of dizziness during exercise had improved and that he was no longer experiencing prodromal palpitations. Follow-up 24 h Holter monitoring at 1 mo (Figure 2B) demonstrated some ventricularprematurebeats but no VT.

Two months later, the patient reported no symptoms of dizziness, and 24 h Holter monitoring showed sinus rhythm without the occurrence of transient VT. These results were maintained at the 6 mo follow-up.

Both bradycardia and tachycardia can precipitate dizziness, and the arrhythmia is more commonly supraventricular than ventricular[4]. The patient described in this case report suffered from transient dizziness during exercise that was caused by a sudden fall in cardiac output secondary to the onset of VT. The patient was otherwise in sinus rhythm and hence asymptomatic. Although exercise-induced VT is not uncommon in patients with myocardial ischemia or structural heart disease, few published studies have described this arrhythmia in patients without these underlying conditions. A very recent case report described a 51-year-old woman without structural heart disease who presented with symptoms of mild chest discomfort and developed sustained VT during an exercise tolerance test[5]. However, to the best of our knowledge, our report is the first to describe transient VT as the cause of exercise-induced dizziness.

VT is a potentially lethal arrhythmia characterized by the occurrence of regular, wide QRS complexes at a rate exceeding 100 beats/min. Although VT is usually associated with organic heart disease, a study in the United States found that 1.1% of asymptomatic people developed exercise-induced VT during a treadmill test, the majority of who were older than 65 years of age[6]. Another study in the United States detected VT in 1.5% of people undergoing routine exercise testing[7]. Most cases of VT in people without evidence of heart disease are thought to originate in the ventricular outflow tract[8].

The case described here highlights the complexity of diagnosing the cause of dizziness in patients presenting to the neurology department. Dizziness is not an uncommon complaint among individuals and is typically related to disorders of the vestibular system in the inner ear, central vestibular lesions, or other neurologic factors[3]. Nevertheless, it is imperative that physicians recognize that not all cases of dizziness are due to peripheral or central causes. Although dizziness is often a transient symptom and benign disorder, it can also be a manifestation of a more serious condition. A thorough history and physical examination are key to guiding the use of appropriate investigations (where necessary) to prevent a delay in diagnosis and treatment. A cardiovascular lesion should be considered in young patients with persistent dizziness, an absence of other neurologic or peripheral symptoms (such as nystagmus, nausea, vomiting, severe ataxia or diplopia), and/or the presence of cardiovascularsymptoms or signs. We recommend 24 h Holter monitoring as a first-choice investigation for patients with a suspected cardiac cause of dizziness, although a more thorough cardiovascular workup may be needed in some cases.

The patient in this study was successfully managed initially with medical therapy (metoprolol) and then with catheter ablation therapy. Beta-blockers are generally considered the first-line option for VT, especially in patients with outflow tract VT, although drugs such as amiodarone, procainamide, and lidocaine can also be used[9]. Catheter-based ablation is an effective treatment for VT and is associated with a reduction of VT burden, improved quality of life, and improved survival in select patients[10-12]. Furthermore, catheter ablation was shown to be better at eliminating recurrent VT than dose escalation of antiarrhythmic drugs[10]. Notably, a meta-analysis of 980 patients concluded that the outcomes of catheter ablation to prevent VT recurrence were better in patients referred earlier[13], emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis and intervention.

The outcome of this case illustrates the benefits to the patient of a careful and thorough clinical examination and appropriate communication with specialized centers. When the clinical suspicion of arrhythmia is high, consultation with a cardiologist and referral to a specialized center may be vital to ensure that patients with potentially serious conditions are treated as soon as possible.

The authors would like to thank the patient and his family for their cooperation in relation to this report.

| 1. | Neuhauser HK. The epidemiology of dizziness and vertigo. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;137:67-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chang J, Hwang SY, Park SK, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Chae SW, Song JJ. Prevalence of Dizziness and Associated Factors in South Korea: A Cross-Sectional Survey From 2010 to 2012. J Epidemiol. 2018;28:176-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Muncie HL, Sirmans SM, James E. Dizziness: Approach to Evaluation and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95:154-162. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Susanto M. Dizziness: if not vertigo could it be cardiac disease? Aust Fam Physician. 2014;43:264-269. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Darmadi MA, Duval A, Khadraoui H, Romero AN, Simon B, Watkowska J, Saint-Jacques H. Exercise-Induced Sustained Ventricular Tachycardia without Structural Heart Disease: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e928242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fleg JL, Lakatta EG. Prevalence and prognosis of exercise-induced nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in apparently healthy volunteers. Am J Cardiol. 1984;54:762-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yang JC, Wesley RC Jr, Froelicher VF. Ventricular tachycardia during routine treadmill testing. Risk and prognosis. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:349-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Biffi A, Pelliccia A, Verdile L, Fernando F, Spataro A, Caselli S, Santini M, Maron BJ. Long-term clinical significance of frequent and complex ventricular tachyarrhythmias in trained athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:446-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tang PT, Do DH, Li A, Boyle NG. Team Management of the Ventricular Tachycardia Patient. ArrhythmElectrophysiol Rev. 2018;7:238-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sapp JL, Wells GA, Parkash R, Stevenson WG, Blier L, Sarrazin JF, Thibault B, Rivard L, Gula L, Leong-Sit P, Essebag V, Nery PB, Tung SK, Raymond JM, Sterns LD, Veenhuyzen GD, Healey JS, Redfearn D, Roux JF, Tang AS. Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation vs Escalation of Antiarrhythmic Drugs. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:111-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 496] [Cited by in RCA: 648] [Article Influence: 64.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Marchlinski FE, Haffajee CI, Beshai JF, Dickfeld TL, Gonzalez MD, Hsia HH, Schuger CD, Beckman KJ, Bogun FM, Pollak SJ, Bhandari AK. Long-Term Success of Irrigated Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation of Sustained Ventricular Tachycardia: Post-Approval THERMOCOOL VT Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:674-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kitamura T, Maury P, Lam A, Sacher F, Khairy P, Martin R, Vlachos K, Frontera A, Takigawa M, Nakatani Y, Thompson N, Massouillie G, Cheniti G, Martin CA, Bourier F, Duchateau J, Klotz N, Pambrun T, Denis A, Derval N, Cochet H, Hocini M, HaissaguerreM, Jais P. Does Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation Targeting Local Abnormal Ventricular Activity Elimination Reduce Ventricular Fibrillation Incidence? Circ ArrhythmElectrophysiol. 2019;12:e006857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Romero J, Di Biase L, Diaz JC, Quispe R, Du X, Briceno D, Avendano R, Tedrow U, John RM, Michaud GF, Natale A, Stevenson WG, Kumar S. Early Versus Late Referral for Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia in Patients With Structural Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Outcomes. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;4:374-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dye DC S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yu HG