Published online Oct 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i29.8938

Peer-review started: June 21, 2021

First decision: July 5, 2021

Revised: July 7, 2021

Accepted: September 2, 2021

Article in press: September 2, 2021

Published online: October 16, 2021

Processing time: 115 Days and 19.2 Hours

Massive upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is usually urgent and severe, and is mostly caused by GI diseases. Aortoesophageal fistula (AEF) after thoracic aortic stent grafting is a rare cause of this condition, and has a poor prognosis with a high mortality rate. The clinical symptoms of AEF are usually nonspecific, and the diagnosis is often difficult, especially when upper GI bleeding is absent. Early identification, early diagnosis, and early treatment are very important for improving prognosis.

A 74-year-old man was admitted to the infectious disease department with > 10-d fever and 10-mo prior history of thoracic aortic stent grafting for thoracic aortic penetrating ulcers. Blood tests revealed elevated inflammatory indicators and anemia. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed postoperative changes of the aorta after endovascular stent graft implantation, pulmonary infection and pleural effusion. Pleural effusion tests showed empyema. After 1 wk of anti-infective treatment, temperature returned to normal and chest CT indicated improvement in pulmonary infection and reduction of pleural effusion. Esophageal endoscopy was performed because of epigastric discomfort, and showed a large ulcer with blood clot in the middle esophagus. However, on day 11, hematemesis and melena developed suddenly. Bleeding stopped temporarily after hemostatic treatment and bedside endoscopic hemostasis. Thoracic and abdominal aortic CT angiography confirmed AEF. Later that day, he suffered massive hemorrhage and hemorrhagic shock. Eventually, his family elected to discontinue treatment.

AEF should be strongly considered in patients with a history of aortic intervention who present with fever, especially with empyema.

Core Tip: Aortoesophageal fistula (AEF) is a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. We present a case of massive upper GI bleeding caused by AEF after thoracic aortic stent grafting. Fever was the main clinical manifestation in the early stage accompanied by later epigastric discomfort. Chest computed tomography showed pulmonary infection and pleural effusion; pleural effusion tests showed empyema. Esophageal endoscopy revealed a large esophageal ulcer. Pulmonary infection and empyema were controlled by antibiotics and symptomatic treatment. However, the patient developed hematemesis and melena (conservative treatment and emergency endoscopic hemostasis were ineffective), subsequently suffering hemorrhagic shock, and discontinued further treatment.

- Citation: Wang DQ, Liu M, Fan WJ. Secondary aortoesophageal fistula initially presented with empyema after thoracic aortic stent grafting: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(29): 8938-8945

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i29/8938.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i29.8938

Aortoesophageal fistula (AEF) is a rare pathologic entity that involves direct communication between the aorta and esophagus. Secondary AEF following operative treatment is rare and almost exclusively occurs in patients with a history of aortic surgery, especially thoracic endovascular aorta repair (TEVAR)[1]. Although the estimated annual incidence of secondary AEF is low at about 0.6%-2%, the associated mortality is 100% without intervention[2]. Because of its rarity, the diagnosis of AEF is often difficult, especially when upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is absent. The clinical symptoms of AEF are typically mid-thoracic pain and sentinel hemorrhage, followed by massive bleeding after a symptom-free interval[2]. However, attention should be paid to nonspecific symptoms in patients with a history of aortic inter-ventions.

Herein, we present a patient with AEF, who initially presented with fever and empyema.

In September, 2020, the patient presented to the infectious disease department of our hospital, complaining of fever for 10 d.

At 10 d before admission, the patient developed a fever, with a peak body temperature of 39.9 °C, accompanied by chills and fatigue. He did not have chest pain or cough.

The patient, a 74-year-old man, had a history of hypertension for 10 years, with the highest blood pressure of 160/90 mmHg, and took perindopril tert-butylamine 8 mg tablets and metoprolol succinate sustained-release 47.5 mg tablets orally once a day. He also had a history of diabetes for 8 years, and took gliclazide 60 mg modified release tablets once a day and metformin hydrochloride 500 mg tablets twice a day. In 2013, he underwent percutaneous transluminal coronary intervention due to coronary atherosclerotic heart disease, and five stents were implanted.

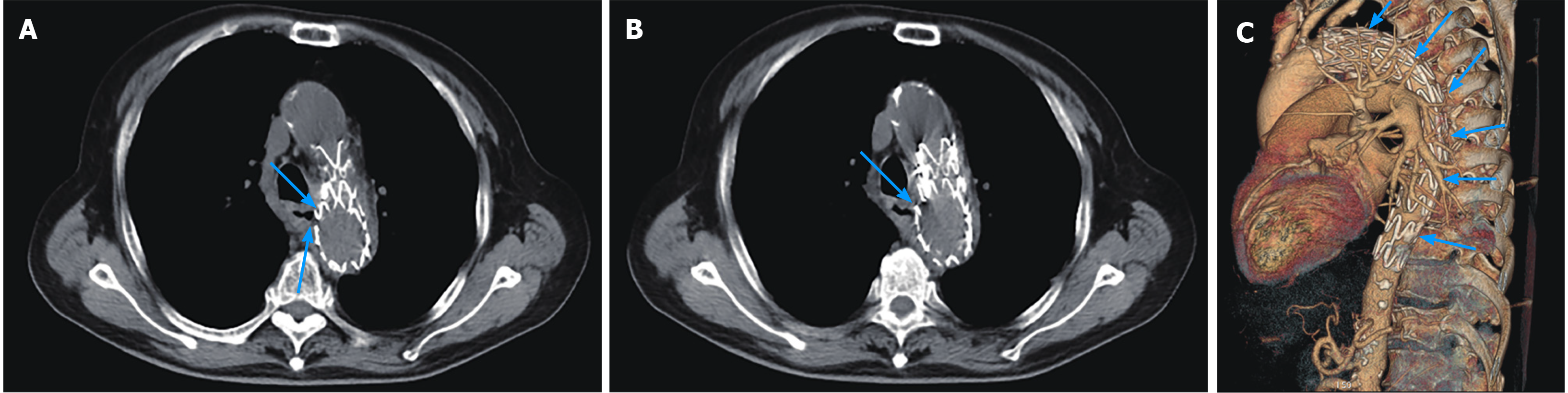

In November, 2019, the patient was admitted to the cardiovascular department in our hospital due to chest pain; thoracic and abdominal aortic computed tomography (CT) angiography showed irregular thickening of the aortic wall with multiple penetrating ulcers and intramural hemorrhage and hematoma (Figure 1). Then, endovascular stent graft implantation of the thoracic aorta was performed and he was administered long-term medication therapy of aspirin (at 100 mg orally once a day) and atorvastatin (at 20 mg orally once every night). Repeat CT angiography in June, 2020 showed postoperative changes of the aorta after endovascular stent graft implantation and reduction of hematoma.

He had a history of smoking for 50 years, with an average of 25 cigarettes per d, and quit smoking in 2019. He denied a history of allergies and had an unremarkable family history.

The patient’s temperature was 38.3 °C, heart rate was 90 beats per min, respiratory rate was 18 breaths per min, and blood pressure was 119/61 mmHg. He had crackling sounds in both lungs, without rhonchi and moist rales. Heart auscultation and abdominal examination were normal and there was no edema of the lower limbs.

Fecal occult blood test was negative. Blood analysis showed normal white blood cells (8.68 × 109/L) with mild neutrophil predominance (77.2%) and moderate anemia [red blood cell (commonly referred to as RBC): 2.73 × 1012/L; hemoglobin (commonly referred to as Hb): 75.0 g/L; hematocrit: 23.4%]. Blood biochemistry showed hypoproteinemia (28.2 g/L) and normal liver and renal function. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein was increased at 81 mg/L (< 1 mg/L) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 85 mm/H. Serum procalcitonin was increased at 1.94 ng/mL ( < 0.05 ng/mL). Infection indexes including mycoplasma, chlamydia, cytomegalovirus, T-Spot, and typhoid were negative and Epstein-Barr virus DNA levels were elevated (4.10 × 103 copies/mL). Immune indexes showed antinuclear antibody of 1:320. Thoracocentesis was performed under ultrasound guidance and the routine pleural effusion tests showed exudate and Rivalta ( + ), RBC 4500 × 106/L, karyocyte count 85000 × 106/L, neutrophil percentage 88%, glucose < 0.11 mmol/L, total protein 51.3 g/L, lactic dehydrogenase > 1867 U/L, and adenosine deaminase 68 IU/L. Pleural effusion tuberculosis smear and bacterial culture were negative and liquid-based cytology showed massive neutrophile granulocytes.

CT scan showed postoperative changes of the aorta after the endovascular stent graft implantation, and patchy soft tissue shadow adjacent to the aorta of the left lower lobe accompanied by cavity formation and pleural effusion, indicating pulmonary infection. At 5 d after admission, the patient complained of epigastric discomfort, so an esophageal endoscopy was performed and showed a large deep longitudinal ulceration (2 cm × 1 cm) with an adherent clot and white coating 25-27 cm from the incisors, and no bleeding (Figure 2A and B). During the endoscopy, a biopsy of the ulcer margin was taken and showed chronic inflammation and granulation tissue hyperplasia. After anti-infective treatment for 1 wk, repeated CT scan showed partial control of the pulmonary infection and reduction of pleural effusion. At 11 d after admission, the patient presented with hematemesis. A second bedside emergency endoscopy showed blood clots and massive bleeding (Figure 2C and D). Endoscopic hemostasis with a norepinephrine spray was performed to control bleeding. Finally, thoracic and abdominal aortic CT angiography showed intravenous contrast material outside the aortic stent graft (Figure 3C, orange arrow), indicating hematoma and extraluminal air near the aortic stent graft (Figure 3). Patchy soft tissue shadows adjacent to the aorta of the left lower lobe was accompanied by cavity and empyema formation (Figure 4). CT scan showed endovascular stent graft communication with the esophagus (Figure 5).

Upper GI hemorrhage, hemorrhagic shock, AEF, empyema, pulmonary infection, multiple penetrating ulcers in the thoracoabdominal aorta, intermural hematoma after thoracic aortic stent grafting, coronary atherosclerotic heart disease after percutaneous coronary intervention, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes.

After admission, cefoperazone and tazobactam [2250 mg every 8 h (referred to as q8h)], and teicoplanin [400 mg once a day (QD)] were given as anti-infective treatments. The patient also received albumin supplementation and fluid infusion to maintain the water and electrolyte balance. Rabeprazole (40 mg QD), hydrotalcite [0.5 g three times a day (referred to as TID)], and mosapride (5 mg TID) were used to improve epigastric discomfort. At 11 d after admission, the patient presented with hematemesis and Hb levels declined to 51.0 g/L. He was treated with terlipressin (1 mg q8h), octreotide (0.3 mg q8h), hemocoagulase atrox (2 U QD), aminomethylbenzoic acid (300 mg QD), etamsylate (2.0 g QD), rabeprazole (40 mg QD), and intravenous blood transfusion (RBC and plasma). Later, the patient presented with massive hematemesis and hemorrhagic shock (drop of blood pressure and oxygen saturation, tachyarrhythmia), and entered a coma. Nikethamide, lobeline, atropine, lidocaine, dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, isoprenaline, and a bilevel positive airway pressure ventilator were used to rescue the patient.

After episodes of hematemesis, the patient suffered from hemorrhagic shock and entered a coma. Finally, his family elected to discontinue treatment.

Upper GI hemorrhage is a common critical illness, mostly caused by diseases of the digestive system, such as peptic ulcers and esophagogastric variceal bleeding[3]. AEF is a rare cause of upper GI hemorrhage, but it is potentially fatal and has a poor prognosis. To date, the existing literature mainly consists of case reports. The first case of AEF was reported in 1818, and the first successfully treated case was reported in 1980[4]. The typical clinical manifestations of AEF are Chiari’s triad, which consists of chest pain, sentinel hemorrhage, and exsanguination after a symptom-free interval[5]. According to the literature, the most common cause of AEF is postoperative aortic disease, followed by primary aortic aneurysm, foreign body ingestion, and thoracic cancer[6]. AEF after TEVAR is rare and unusual, with an incidence of about 1.5%-1.9%. The most common clinical manifestations are unexplained fever, followed by hematemesis and shock[7,8]. The main clinical manifestation of our patient was fever and subsequent hematemesis and hemorrhagic shock, in accordance with the literature. Thoracocentesis and the routine pleural effusion tests had confirmed empyema, which we initially thought was a complication of pulmonary infection and we ignored its cause by esophageal perforation. Therefore, we suggest new-onset fever may be a clinical symptom that suggests AEF after TEVAR, especially when combined with empyema. Sometimes upper GI bleeding is absent; thus, AEF should be strongly considered in patients with a history of aortic intervention who present with a fever and elevated inflammatory markers.

AEF remains a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, and the rate of diagnosis within 10 d of hospitalization is only 15%[9]. The diagnosis of AEF mainly depends on CT and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (commonly referred to as EGD). However, the diagnostic sensitivity of endoscopy and CT for AEF is 24% and 45%, respectively[9]. CT scan results suggestive of AEF include a new heterogeneous mass with or without air entrapment between the aorta and esophagus, visible graft, swelling or hematoma around the graft, intravenous contrast within the GI lumen or around the aorta, and loss of calcification or tear in the aortic wall[7,10]. Findings that are indicative of AEF on EGD include visible graft, bleeding, adherent clot, ulcer, and pulsatile mass in the esophagus[11,12]. In this case study, the patient went to the infectious department due to fever. Chest CT showed signs of lung infection and pleural effusion but no new hematoma between the esophagus and aorta. The first EGD showed an esophageal ulcer, which was difficult to distinguish from esophageal ulcer caused by other diseases. Fecal occult blood test was negative. Therefore, in the initial treatment plan, the doctor focused on controlling the patient’s infection with antibiotics. When the patient had hematemesis for the first time, the amount of bleeding was relatively large, and hemostatic therapy was ineffective; thus, emergency bedside endoscopic hemostasis was performed before thoracic and abdominal aortic CT angiography. After confirmation of AEF, the patient suffered from hemorrhagic shock. Due to complicated underlying diseases and high surgical risk, his family members elected to discontinue treatment. However, after carefully reviewing this case, we found that the patient had symptoms of stomach discomfort during hospitalization. Although there was no hematemesis or melena in the early stage and fecal occult blood test was negative, routine blood test indicated moderate anemia and fatigue began to appear 1 d before massive GI bleeding. These findings indicated that the patient already had blood loss before hematemesis. Thus, esophageal endoscopy should be performed carefully and the procedure should be terminated if a fistula is identified.

The mechanisms of AEF after TEVAR are unclear and may be related to the following aspects: Direct erosion of the aorta and esophagus by the relatively rigid stent-graft; continuous pressure on the stent-graft causing esophageal necrosis; stent-graft compression of the aortic side branches that feed the esophagus and cause avascular necrosis of the esophageal wall; and, stent-graft infection extending to the esophagus and eroding the esophageal wall[8,13]. In this case, we can see from Figure 5A and 5B that the aortic stent graft protruded to the esophagus, possibly due to stent direct erosion. The appearance of chronic esophageal perforation was followed by mediastinitis, empyema, and fever.

The treatment of AEF should be individualized according to the cause and patient’s condition. Treatment options include conservative treatment, TEVAR, aortic fistula repair, graft replacement for aortic lesions, esophagectomy, esophageal stent, esophageal fistula repair, and combination therapy of esophagus (esophagectomy, esophageal stent or repair) and aorta (TEVAR, graft replacement or repair)[6]. In terms of treatment, we adopted a conservative treatment and endoscopic hemostatic treatment, but they were all ineffective. Also, the surgical risk for this patient was high and his family members declined the offer to perform surgery. AEF after TEVAR is complicated and more difficult to treat. Some authors recommend treating secondary AEF with surgery. For surgical treatment, secondary TEVAR alone is not an effective treatment; in the emergency phase, it was used to seal the fistula and control bleeding but open surgery was still needed. Moreover, in the later stage, there may be adverse outcomes due to persistent mediastinal infection or sepsis and tissue adhesion after TEVAR[14-16]. Combined treatment involves removal of the infected tissue and reconstruction of the aorta and esophagus, for example, conducting vascular bypass in stage 1, stent-graft resection, and esophageal repair in stage 2[17]. However, in clinical practice, due to individual differences, not every patient is eligible for surgery, and complications during and after surgery may eventually lead to adverse outcomes. Therefore, early diagnosis and multidisciplinary cooperation are very important. AEF must be considered as a possible etiology of GI bleeding, chronic fever, and other nonspecific symptoms in patients with a history of aortic interventions.

Upper GI bleeding caused by AEF after TEVAR is rare but has a high mortality rate. The diagnosis of AEF remains a challenge, and AEF should be strongly considered in patients with a history of aortic intervention who present with a fever, elevated inflammatory markers and pleural effusion, even if upper GI bleeding is absent. Early identification, early diagnosis, and early surgical treatment are expected to further improve the outcome of AEF.

| 1. | Gomes SIM, de Campos FPF, Martines BMR, Martines JADS, Tafner E, Maruta LM. Primary aortoesophageal fistula: a rare cause of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Autops Case Rep. 2011;1:57-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Monteiro AS, Martins R, Martins da Cunha C, Moleiro J, Patrício H. Primary Aortoesophageal Fistula: Is a High Level of Suspicion Enough? Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7:001666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wuerth BA, Rockey DC. Changing Epidemiology of Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage in the Last Decade: A Nationwide Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:1286-1293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ctercteko G, Mok CK. Aorta-esophageal fistula induced by a foreign body: the first recorded survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1980;80:233-235. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Heckstall RL, Hollander JE. Aortoesophageal fistula: recognition and diagnosis in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32:502-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Takeno S, Ishii H, Nanashima A, Nakamura K. Aortoesophageal fistula: review of trends in the last decade. Surg Today. 2020;50:1551-1559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Eggebrecht H, Mehta RH, Dechene A, Tsagakis K, Kühl H, Huptas S, Gerken G, Jakob HG, Erbel R. Aortoesophageal fistula after thoracic aortic stent-graft placement: a rare but catastrophic complication of a novel emerging technique. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:570-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Czerny M, Eggebrecht H, Sodeck G, Weigang E, Livi U, Verzini F, Schmidli J, Chiesa R, Melissano G, Kahlberg A, Amabile P, Harringer W, Horacek M, Erbel R, Park KH, Beyersdorf F, Rylski B, Blanke P, Canaud L, Khoynezhad A, Lonn L, Rousseau H, Trimarchi S, Brunkwall J, Gawenda M, Dong Z, Fu W, Schuster I, Grimm M. New insights regarding the incidence, presentation and treatment options of aorto-oesophageal fistulation after thoracic endovascular aortic repair: the European Registry of Endovascular Aortic Repair Complications. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;45:452-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pipinos II, Carr JA, Haithcock BE, Anagnostopoulos PV, Dossa CD, Reddy DJ. Secondary aortoenteric fistula. Ann Vasc Surg. 2000;14:688-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Malik MU, Ucbilek E, Sherwal AS. Critical gastrointestinal bleed due to secondary aortoenteric fistula. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2015;5:29677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nazarewicz GV, Jain R. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Caused by Aortoesophageal Fistula. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:A22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Soga K, Kitamura R, Takenaka S, Kassai K, Itani K. Progressive endoscopic findings in a case of aortoesophageal fistula. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Czerny M, Rylski B, Schuster I, Kari F, Siepe M, Beyersdorf F. Secondary organ fistulation after thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2015;24:305-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Canaud L, Ozdemir BA, Bee WW, Bahia S, Holt P, Thompson M. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair in management of aortoesophageal fistulas. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:248-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dorweiler B, Weigang E, Duenschede F, Pitton MB, Dueber C, Vahl CF. Strategies for endovascular aortic repair in aortobronchial and aortoesophageal fistulas. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;61:575-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sugiyama K, Iwahashi T, Koizumi N, Nishibe T, Fujiyoshi T, Ogino H. Surgical treatment for secondary aortoesophageal fistula. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;15:251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhu Y, MacArthur JW, Lui NS, Lee AM. Surgical Management for Aortoesophageal Fistula After Endovascular Aortic Repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109:1611-1613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Raissi D S-Editor: Chang KL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ