Published online Oct 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i29.8888

Peer-review started: June 8, 2021

First decision: June 25, 2021

Revised: July 8, 2021

Accepted: August 4, 2021

Article in press: August 4, 2021

Published online: October 16, 2021

Processing time: 129 Days and 3.5 Hours

Tracheal tumors are relatively rare in adults and uncommon in children. Tracheal neurilemmoma is a rare condition in adults that usually affects middle-aged people, but it can also occur in children. Because the clinical presentation is nonspecific and insidious, diagnosis is often delayed. The most common symptoms in these patients are stridor or wheezing (especially positional) and cough. A few patients are misdiagnosed and mistakenly treated for asthma.

A 10-year-old girl was admitted to our unit with a 2-mo history of recurrent cough, dyspnea, and tachypnea. Her condition was more severe after exercise. Her symptoms progressed despite treatment with inhaled fluticasone/salmeterol. Flexible electronic laryngoscopy showed a red, smooth, and round mushroom-shaped mass in the trachea, about 1 cm below the vocal cords. The surface of the mass was covered with several small and discontinuous blood vessels. About 90% of the tracheal lumen was occupied by the mass. A multidisciplinary operation was performed. The surgically resected mass was diagnosed as benign neurilemmoma by immunohistochemical analysis.

Intratracheal neurilemmoma is fairly rare in children. The main symptoms include coughing, wheezing, and dyspnea. The tumor’s size, location, and degree of intratracheal and extratracheal invasion can be measured by chest computed tomography. The main treatment strategies used for tracheal neurilemmoma are surgical resection and endoscopic excision. Long-term follow-up is warranted for the evaluation of outcomes and complications.

Core Tip: Tracheal neurilemmoma is a rare condition in children. Because the clinical presentation is nonspecific and insidious, diagnosis is often delayed. This case report describes a 10-year-old girl with tracheal neurilemmoma.

- Citation: Wu L, Sha MC, Wu XL, Bi J, Chen ZM, Wang YS. Primary intratracheal neurilemmoma in a 10-year-old girl: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(29): 8888-8893

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i29/8888.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i29.8888

Tracheal tumors are relatively rare in adults and uncommon in children[1]. About two-thirds of such tumors are malignant or moderately malignant, and the remaining one-third are benign lesions[2]. Tracheal neurilemmoma, also known as schwannoma, is a rare condition in adults that usually affects middle-aged people; however, it can also occur in children[3]. Common symptoms of this condition are stridor or wheezing and coughing. Some patients are misdiagnosed and mistakenly treated for asthma. This report describes a case involving a 10-year-old girl with tracheal neurilemmoma.

A 2-mo history of recurrent cough, dyspnea, and tachypnea.

A 10-year-old girl was admitted to our unit with a 2-mo history of recurrent cough, dyspnea, and tachypnea. Her condition was more severe after exercise. She had been hospitalized twice in a local unit and diagnosed with bronchitis and asthma. Her symptoms progressed despite treatment with inhaled fluticasone/salmeterol.

The patient had been previously healthy, and she denied a history of asthma and seasonal allergic rhinitis.

The patient had no relevant family history.

On admission, the patient was dyspneic and characterized by biphasic stridor with a percutaneous saturation of 95% on room air. An examination showed a body temperature of 36.7 ºC, a pulse rate of 92 beats/min, a respiration rate of 34 breaths/min, and a blood pressure of 107/74 mmHg.

The patient’s leukocyte count was 6.07 × 109/L (reference range: 4.0-12.0 × 109/L). Her lymphocyte count was 3.09 × 109/L (reference range: 0.7-4.9 × 109/L). An immune function test showed that her immunoglobulins were within the reference range.

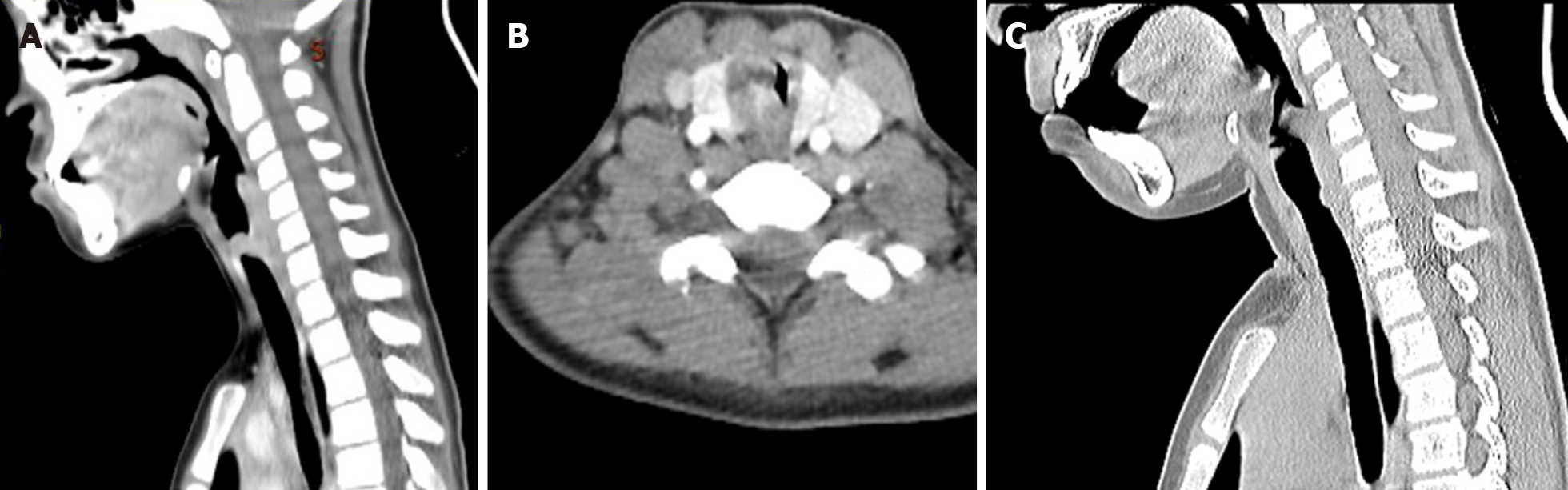

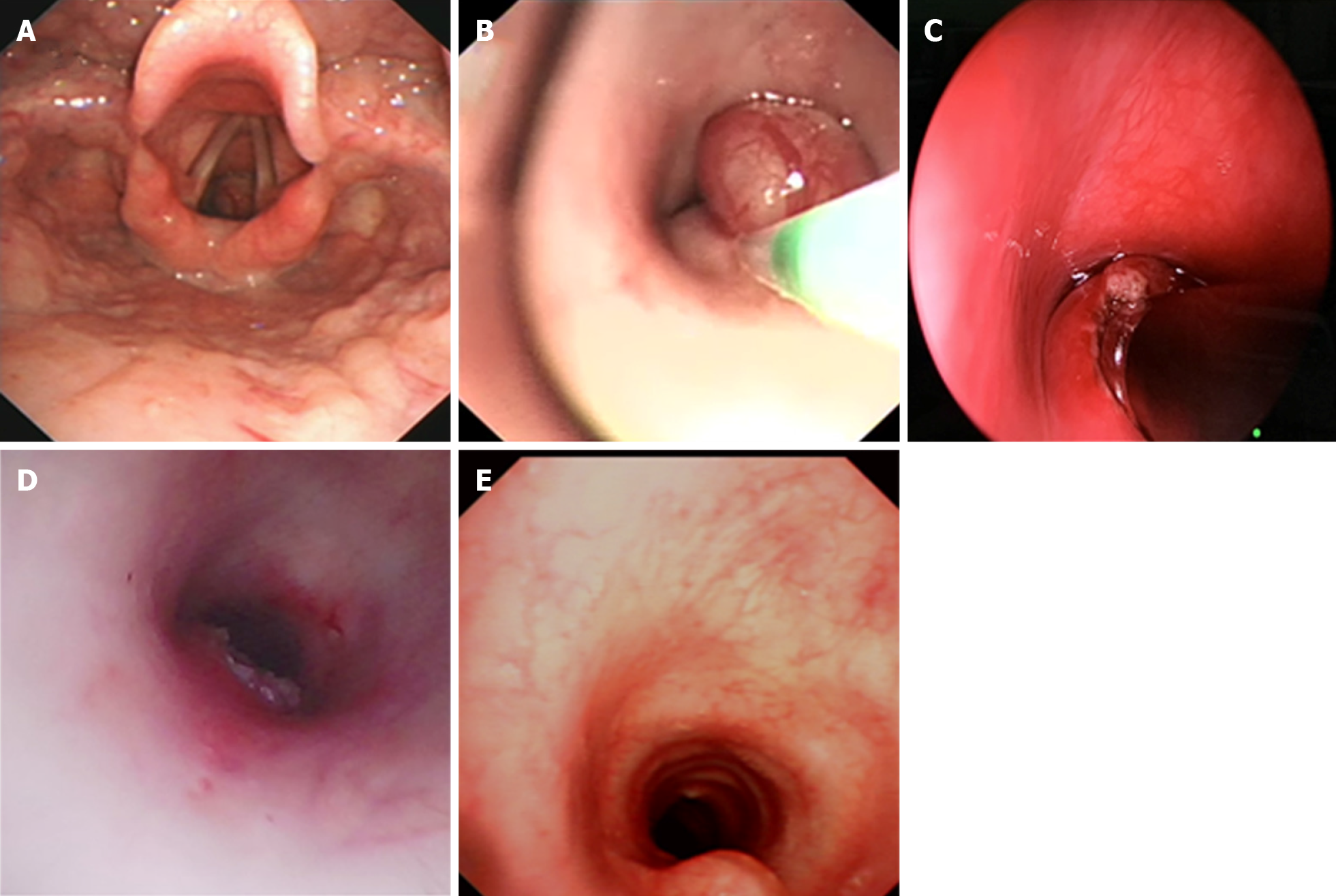

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed an obviously enhanced mass, occluding about 90% of the tracheal lumen (Figure 1A and B). Under conscious and local anesthesia, flexible electronic laryngoscopy showed a red, smooth, and round mushroom-shaped mass. The surface of the mass was covered with several small and discontinuous blood vessels. The base of the mass was in the trachea, about 1 cm below the vocal cords at the 4- to 7-o’clock position (Figure 2A).

Pulmonary function examinations indicated that the patient, who had exhibited no marked response to bronchodilators, had severe inspiratory obstructive ventilation dysfunction.

According to the pathological and immunohistochemical examination findings, the patient was diagnosed with tracheal neurilemmoma.

The multidisciplinary consensus met the performance of endoscopy for a definitive diagnosis and determined prognosis and guide management. After the patient’s parents had been fully notified of surgical options and possible complications associated with the various surgical modalities, they agreed to endoscopic tumor resection. There was a rigid bronchoscope available as well as a low-temperature plasma therapy device, argon plasma coagulation device, cryotherapy device, and holmium laser if necessary. The patient’s parents also consented that, in case of failed endoscopic tumor resection, surgical resection would be conducted instantly.

Otolaryngologists, pulmonologists, anesthesiologists, thoracic surgeons, and doctors of the pediatric intensive care department were on-call in the operating room, ensuring the patient’s safety. The loading dose of dexamethasone was 1 µg/kg, and the maintenance rate was 0.3 µg/kg/h. The patient was maintained with 3% sevoflurane inhalation, remifentanil at 0.2 µg/kg/min, intravenous methylprednisolone at 30 mg, intravenous atropine at 0.25 mg, and intravenous lidocaine at 25 mg. After deep sedation and spontaneous breathing were achieved, 10 mg of etomidate was added to deepen the anesthesia. A flexible bronchoscope (FB) with a 2.8 mm outer diameter (Olympus XP260; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was inserted into the trachea over the mass and used to guide intubation of a 4.5 mm endotracheal tube. The 4.5-mm tube could not prevent blood from flowing into the lower airway; therefore, we decided to perform a tracheotomy below the mass. The anesthesia ventilator controlled the patient’s breathing through a tracheotomy cannula. After extubation of the endotracheal tube, a laryngoscope was placed in the vallecula, exposing the supraglottic and glottic larynx. An FB with a 4.9 mm outer diameter (Olympus 260; Olympus Corp.) was then passed into the subglottic region. A flexible electrocautery snare with a 1.9 mm outer diameter (Olympus CD-6C-1; Olympus Corp.) was then inserted via the working channel of the FB. The electrocautery snare was applied in a blended way at 12 W for cutting and coagulating the spherical part of the mass (Figure 2B). Because the mass base was too wide to be removed by the electric snare, it was ablated using a low-temperature plasma therapy device (EIC7070-01; Smith and Nephew, London, United Kingdom) under the laryngoscope (Figure 2C). To prevent a tracheoesophageal fistula, the base of the tumor was not completely removed (Figure 2D). The extracorporeal membrane oxygenation team was present to administer emergency treatment if intubation was difficult or asphyxia occurred.

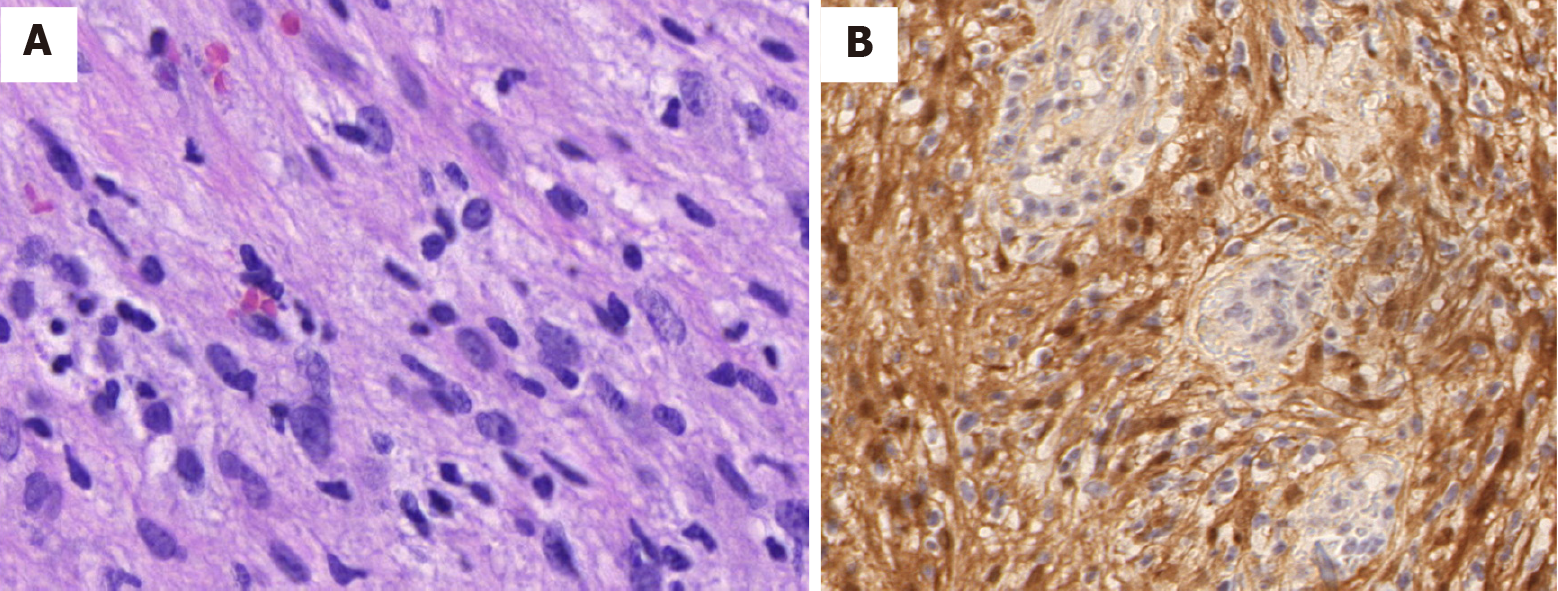

The tumor consisting of bundles of spindle cells with slender palisade nuclei, as shown by staining with hematoxylin and eosin (Figure 3A). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that the positive indicator of the tumor was S-100, and the results of CD117, desmin, smooth muscle actin, and CD34 were negative for the tumor (Figure 3B). The histological and immunohistochemical findings were consistent with benign schwannoma.

The patient’s clinical manifestations disappeared after removal of the tumor, and the tracheotomy cannula was successfully removed 1 wk after the operation. Repeat bronchoscopy and chest CT examinations were conducted for 6 mo after the procedure (Figure 1C). A slight protrusion was present at the position of the incision (Figure 2E).

Neurilemmomas, also known as schwannomas, originate from Schwann cells in the peripheral nerve tissues and are usually benign. They are more commonly reported in the head, retroperitoneum, neck, lungs, and extremities[2]. However, tracheal neurilemmomas are rare in children.

In general, neurilemmomas grow slowly. Because their clinical presentation is nonspecific and insidious, diagnosis is often delayed. Only when the tumor attains a large size can patients be diagnosed. The main symptoms include coughing, wheezing, and dyspnea[4]. Pulmonary function testing is an effective method to distinguish tracheal neurilemmomas from asthma[5,6]. Chest CT or magnetic resonance imaging can be used to measure the tumor’s size, location, and degree of intratracheal and extratracheal invasion. In this case, we reviewed the examination results before admission. Two months previously, we had discovered a mass in the upper part of the trachea. Lung function testing had also indicated an inspiratory phase obstruction, but it was initially ignored. In patients with an atypical presentation of asthma but with no response to anti-asthma treatment, bronchoscopy can detect airway tumors early and avoid misdiagnosis.

Because of the high degree of airway obstruction in this patient, extensive preoperative planning was necessary in case of an airway emergency during the operation. We planned to insert a 4.5-mm endotracheal tube under bronchoscopic guidance after anesthetic induction. Because the endotracheal intubation affected the exposure of the tumor, it would have been difficult to repeat the intubation in case of intraoperative decannulation. The 4.5-mm tube could not prevent blood from flowing into the lower airway, so we performed a tracheotomy below the tumor. If it had been difficult to intubate the patient by bronchoscopy, we would have attempted rigid bronchoscopy. Once a patient has developed obvious airway obstruction or asphyxia after induction of anesthesia, emergency tracheotomy or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation should be considered.

The tumor’s size, location, depth of tracheal wall invasion, and extratracheal involvement should be considered when treating primary tracheal neurilemmoma[7]. The main treatment strategies are surgical resection and endoscopic excision[8]. Traditionally, the best conduit for the management of endotracheal tumors is probably rigid bronchoscopy[8]. Because the tumor in our patient was in the upper trachea and occupied most of the airway, we initially attempted to use an electric snare to remove the tumor. Electrocautery snares can sever large masses quickly with concomitant hemostasis. However, because the base of the tumor was broad, the snare could not remove it. We chose coblation to remove the base of the tumor and reduce the probability of recurrence after electrocautery snaring. The advantages of coblation include rapid and precise ablation, minor thermal damage, and the integrated function of suction and coagulation[9]. Because of these characteristics of coblation technology, there was minimal surrounding tissue damage, which minimized the likelihood of postoperative stenosis.

Although a small part of the tumor remained after its removal, the patient displayed no symptoms and her parents were opposed to further invasive open surgery. Nearly one-fourth of patients who undergo endoscopic resection develop recurrence. The time of recurrence is variable, but there is a chance of late recurrence. Given that these tumors grow slowly, it is preferable to performed yearly bronchoscopic observations. If the tumor continues to grow, tracheal resection is the best option. Outcomes and complications, such as airway stenosis and tumor recurrence, should be consistently evaluated under long-term follow-up.

Intratracheal neurilemmoma is relatively rare in children. Primary symptoms include coughing, wheezing, and dyspnea. Chest CT can be used to measure the tumor’s size, location, and degree of intratracheal and extratracheal invasiveness. The primary treatment strategies used for tracheal neurilemmoma are surgical resection and endoscopic excision. Long-term follow-up is warranted for the evaluation of outcomes and complications.

| 1. | Nio M, Sano N, Kotera A, Shimanuki Y, Takeyama J, Ohi R. Primary tracheal schwannoma (neurilemoma) in a 9-year-old girl. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:E5-E7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sharma PV, Jobanputra YB, Perdomo Miquel T, Schroeder JR, Wellikoff A. Primary intratracheal schwannoma resected during bronchoscopy using argon plasma coagulation. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tang LF, Chen ZM, Zou CC. Primary intratracheal neurilemmoma in children: case report and literature review. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40:550-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hamouri S, Novotny NM. Primary tracheal schwannoma a review of a rare entity: current understanding of management and followup. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;12:105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Weiner DJ, Weatherly RA, DiPietro MA, Sanders GM. Tracheal schwannoma presenting as status asthmaticus in a sixteen-year-old boy: airway considerations and removal with the CO2 laser. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1998;25:393-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen H, Zhang K, Bai M, Li H, Zhang J, Gu L, Wu W. Recurrent transmural tracheal schwannoma resected by video-assisted thoracoscopic window resection: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e18180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ge X, Han F, Guan W, Sun J, Guo X. Optimal treatment for primary benign intratracheal schwannoma: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:2273-2276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Diaz-Mendoza J, Debiane L, Peralta AR, Simoff M. Tracheal tumors. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2019;25:336-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kitsko DJ, Chi DH. Coblation removal of large suprastomal tracheal granulomas. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:387-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Velikova TV S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH