Published online Oct 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i29.8763

Peer-review started: June 11, 2021

First decision: June 25, 2021

Revised: June 26, 2021

Accepted: August 31, 2021

Article in press: August 31, 2021

Published online: October 16, 2021

Processing time: 126 Days and 5.1 Hours

Midazolam is commonly used for sedation during gastrointestinal procedures. However, some patients experience paradoxical reactions characterized by excessive movement or excitement.

To investigate the rate of recurrence of paradoxical reactions to midazolam during an upper endoscopy.

We retrospectively reviewed 122152 sedative endoscopies among a total of 58553 patients at the Seoul National University Hospital, Healthcare System Gangnam Center, from July 2013 to December 2018. Among them, 361 patients with a history of paradoxical reaction during sedative upper endoscopy were enrolled. The characteristics of patients in the recurrent and non-recurrent groups were compared via multivariable analysis using logistic regression.

Paradoxical reactions occurred in 0.86% (1054/122152) of endoscopies, and in 1.51% (888/58553) of patients. Among the 361 subjects with previous paradoxical reactions in sedative endoscopies, 111 (30.7%) experienced further paradoxical reactions. Univariable analysis revealed that the total midazolam dose used was higher in the recurrent group (6.74 ± 2.58 mg) than in the non-recurrent group (5.49 ± 2.04 mg; P < 0.0001). Patients were administered a lower dose of midazolam than previous doses: 1 mg less in the recurrent group and 2 mg less in the non-recurrent group. Multivariable analysis showed that the midazolam dose difference was an independent risk factor for recurrent paradoxical reaction (odds ratio: 1.213, 95%CI: 1.099-1.338, P = 0.0001).

The rate of recurrence of paradoxical reactions is significantly associated with midazolam dosage. The dose of midazolam administered to patients with previous paradoxical reactions should be less than that previously used.

Core Tip: A paradoxical reaction refers to an unexpectedly increased excitement and excessive movement, as opposed to the anxiolytic or sedative effect of midazolam. This is the first study to investigate the recurrence rate of paradoxical reactions to midazolam during upper endoscopy under sedation. We report that the rate of recurrence of paradoxical reactions is significantly associated with the dose of midazolam administered. To avoid the recurrence of such reactions, we recommend reducing the total dose of midazolam administered to patients with previous paradoxical reactions by ≥ 2 mg compared to the dose previously used.

- Citation: Jin EH, Song JH, Lee J, Bae JH, Chung SJ. Midazolam dose is associated with recurrence of paradoxical reactions during endoscopy. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(29): 8763-8772

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i29/8763.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i29.8763

Sedation is provided during gastrointestinal endoscopy to relieve anxiety and discomfort, improve patient cooperation and satisfaction, and increase repeat endoscopy compliance[1,2]. Although a number of sedatives are available, midazolam is one of the most commonly used sedatives for gastrointestinal endoscopy because of its rapid onset, short duration of action, and potent amnestic properties[3]. The use of propofol has recently increased as its action and recovery is quicker than that associated with midazolam, although adverse respiratory or cardiovascular events often occur and propofol-induced sedation cannot be reversed[4]. With regard to safety, midazolam remains the best sedative for upper endoscopy as the specific benzodiazepine receptor antagonist flumazenil can be used to reverse any midazolam-associated adverse effects[5].

Unfortunately, some patients who receive midazolam may experience unexpectedly increased excitement and excessive movement. This is known as a “paradoxical reaction” because the effect is opposite to that commonly associated with sedatives and anxiolytics[6]. Paradoxical reactions are characterized by increased loquacity, emotional release, excitement, excessive movement, and even hostility[7]. Patients with severe paradoxical reactions may become dangerous to themselves and the endoscopy team, and the procedure may be interrupted. The incidence of paradoxical reactions to midazolam vary greatly among different reports, ranging from 1% to 24%[8]. In addition, the pathophysiological mechanism of paradoxical reactions remains unclear, although several predisposing risk factors are suggested, including age, gender, history of alcohol consumption, genetic predisposition, previous unsuccessful sedation, previous upper endoscopy, and high midazolam dose used[6-8].

In our experience, paradoxical reactions to intravenous midazolam are occasionally observed clinically but have rarely been reported in the literature. Furthermore, the recurrence rate and risk factors associated with recurrent paradoxical reactions are unknown. Doctors treating patients with a history of paradoxical reactions to midazolam may be concerned about the use of sedatives during endoscopic procedures. In this study, we aimed to elucidate the recurrence rate of paradoxical reactions to midazolam in adults undergoing upper endoscopy. Furthermore, we evaluated the risk factors associated with recurrent paradoxical reactions.

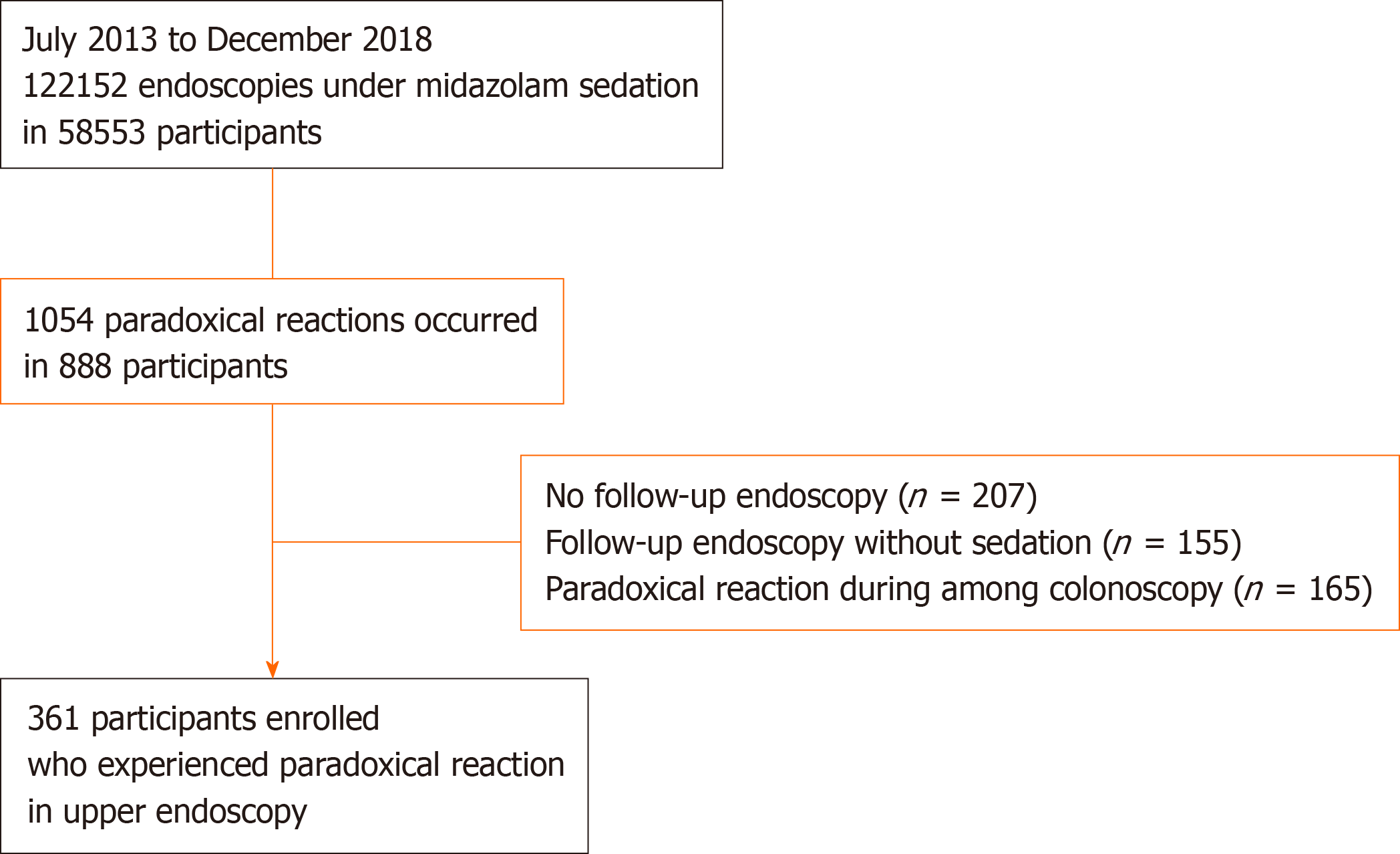

We retrospectively reviewed 122152 cases of sedative endoscopy at the Seoul National University Hospital, Healthcare System Gangnam Center, from July 2013 to December 2018. We identified 1054 cases (888 subjects) of paradoxical reactions to midazolam during sedative endoscopy. Exclusion criteria were as follows: No follow-up endoscopy (n = 207), follow-up endoscopy without sedation (n = 155), and paradoxical reaction during colonoscopy only (n = 165). Finally, a total of 361 subjects with a history of paradoxical reaction during sedative upper endoscopy were enrolled in this study (Figure 1). All participants underwent endoscopy as a routine health check-up and completed self-reported questionnaires describing comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia), medication use (antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics), smoking status (never, ex-, or current smoker), alcohol consumption (none to minimal, < 70 g/wk; moderate, 70-279 g/wk; or heavy, > 280 g/wk). This study protocol conformed with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions and was approved by the relevant institutional review board (No. H-1710-023-890).

All upper gastrointestinal endoscopies were carried out using a conventional white-light video endoscope (GIF-H260 or H290 series endoscopes, Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) by one of 16 board-certified gastroenterologists. Clinicians were divided into three groups based on their level of endoscopic experience: Highly expert (> 15 years of experience), expert (10-15 years), and less experienced (< 10 years). All participants received midazolam under supervision after topical anesthesia using a pharyngeal spray containing lidocaine. The initial dose of midazolam was 2.0-3.0 mg and was administered slowly intravenously and titrated with additional 0.5-1.0 mg midazolam every 2 min until adequate sedation was achieved. Smaller doses may be used in elderly patients. The target level of sedation for upper endoscopy is moderate sedation, during which patients should be able to make purposeful responses to verbal or tactile stimulation. A trained registered nurse monitored the patient’s blood pressure, heart rate, pulse oximetry, and ventilator status during the procedure, and recorded the midazolam dose used (initial and additional dose), sedation level. Both attending physicians and nurses judged the presence or absence of paradoxical reactions after the procedure. If a subject displayed a paradoxical reaction, the severity, number of assistants required, and flumazenil administration were recorded in the “paradoxical reaction report.”

A paradoxical reaction was defined as unexpected behavior after midazolam injection with at least one of the actions described here. Furthermore, we categorized the severity of paradoxical reactions using modified cooperation scores[9]: (1) Mild: Increased talkativeness, irrational talking, or brief spontaneous movement while remaining in position; (2) Moderate: restlessness, loss of cooperation, or spontaneous movements requiring repositioning without need of restraint; and (3) Severe: agitation and hostile movements requiring restraint by three or more assistants. Moderate and severe paradoxical reactions were recorded in the “paradoxical reaction report.” In cases of severe paradoxical reactions that compromised the safety of the procedure, the attending endoscopist administered flumazenil.

All participants showed previous paradoxical reactions to midazolam during upper endoscopy. We calculated the midazolam dose difference by subtracting the dose of midazolam administered during the previous procedure from that administered during the current procedure: Δ midazolam dose difference = current midazolam dose (mg) - previous midazolam dose (mg). Categorical data analysis was conducted using a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, and continuous data were analyzed using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Multivariable analysis by logistic regression was performed to identify independent predictors of recurrent paradoxical reactions to midazolam during upper endoscopy. P values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All calculations were performed using R software version 3.6.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

We performed a total of 122152 gastrointestinal endoscopies under sedation using midazolam in 58553 participants [49.4 ± 11.6 years, male: 29915 (51.1%), female: 28628 (48.9%)]. Paradoxical reactions occurred in 1054 cases and in 888 participants [53.2 ± 9.7 years, male: 480 (60.5%), female: 314 (39.5%)]. The overall incidence of paradoxical reaction was 0.86% (1054/122152 endoscopic cases), occurring in 1.51% of patients (888/58553). Among the 361 subjects with a history of paradoxical reactions in sedative upper endoscopy, 111 subjects experienced recurring paradoxical reactions during follow-up upper endoscopy under sedation. Therefore, the recurrence rate for paradoxical reactions was 30.7% (111/361). No subjects showed bradycardia, hypotension, or hypoxemia during sedation.

In the recurrent group, 31 patients (27.9%) showed moderate paradoxical reactions, demonstrating excessive movement requiring repositioning, and 80 (72.1%) showed severe paradoxical reactions, with agitation and hostile movement requiring restraint by three or more assistants. Flumazenil was administrated to 26 subjects when the attending endoscopist decided that the paradoxical reaction severely limited the performance of the endoscopy. After flumazenil administration, upper endoscopies were successfully completed in 88.5% of cases (23/26). The procedure could not be completed in three cases as the participants refused to undergo further endoscopy after awaking from flumazenil sedation.

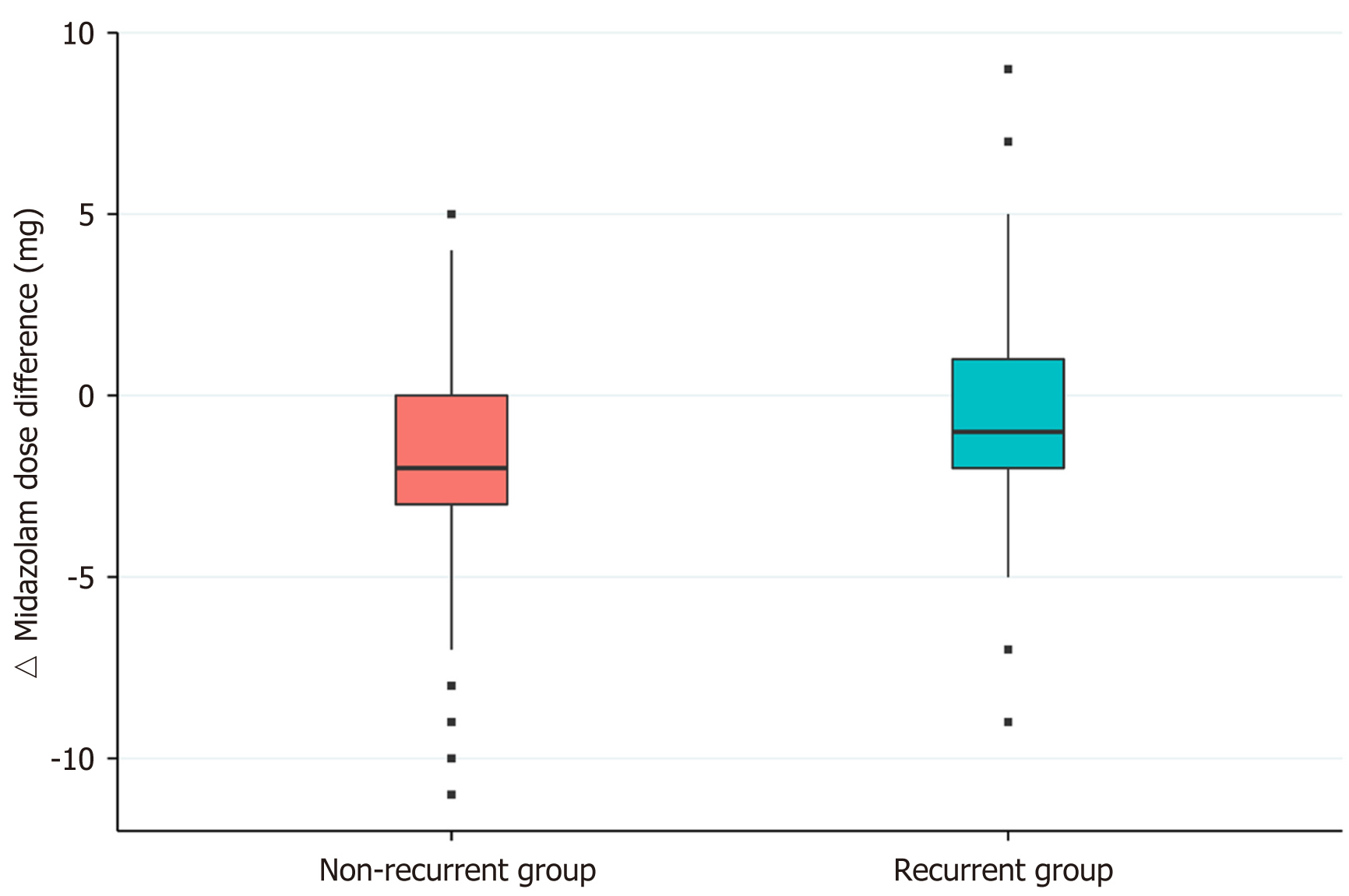

The baseline characteristics of patients in the non-recurrent and recurrent groups are summarized in Table 1. Age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and underlying disease were not significantly different between the two groups. Table 2 presents the results of a univariate analysis of procedure-related factors for recurrent paradoxical reactions. The initial doses administered did not differ between the recurrent and non-recurrent groups. The total midazolam dose was higher in the recurrent group (6.74 ± 2.58 mg) than in the non-recurrent group (5.49 ± 2.04 mg, P < 0.0001). Compared to that in the previous study, the non-recurrent group received a median 2 mg reduced dose of midazolam and the recurrent group received a median 1 mg reduced dose (P < 0.0001). In a multivariable analysis, this midazolam dose difference was an independent risk factor for recurrent paradoxical reactions (odds ratio: 1.213, 95%CI: 1.099-1.338, P = 0.0001; Table 3, Figure 2).

| Non-recurrent group (n = 250), n (%) | Recurrent group (n = 111), n (%) | P value | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 49.57 ± 9.22 | 51.15 ± 9.67 | 0.1395 |

| Sex, male | 165 (66) | 67 (60.36) | 0.3022 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD) | 23.74 ± 3.3 | 24.3 ± 3.69 | 0.1552 |

| Smoking | 0.8010 | ||

| Never | 82 (40.39) | 33 (37.93) | |

| Ex-smoker | 68 (33.5) | 28 (32.18) | |

| Current smoker | 53 (26.11) | 26 (29.89) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.9465 | ||

| None to minimal (< 70 g/wk) | 120 (51.28) | 51 (52.58) | |

| Moderate (70-279 g/wk) | 82 (35.04) | 34 (35.05) | |

| Heavy (> 280 g/wk) | 32 (13.68) | 12 (12.37) | |

| Medication1 | 8 (3.4) | 3 (3.09) | 1.000 |

| HTN (Yes) | 54 (21.6) | 30 (27.03) | 0.2601 |

| DM (Yes) | 19 (7.6) | 6 (5.41) | 0.4485 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 56 (22.4) | 29 (26.13) | 0.4413 |

| Non-recurrent group (n = 250) | Recurrent group (n = 111) | P value | |

| Endoscope type, n (%) | 0.0765 | ||

| H260 | 157 (62.8) | 59 (53.64) | |

| H290 | 90 (36) | 51 (46.36) | |

| Endoscopist experience, n (%) | 0.4251 | ||

| Less experienced | 75 (30) | 41 (36.94) | |

| Expert | 106 (42.4) | 43 (38.74) | |

| Highly expert | 69 (27.6) | 27 (24.32) | |

| Midazolam dose (mean ± SD) | |||

| Initial (mg) | 3.98 ± 1 | 4.19 ± 1.16 | 0.1804 |

| Initial (mg/kg) | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.4070 |

| Total (mg) | 5.49 ± 2.04 | 6.74 ± 2.58 | < 0.0001 |

| Total (mg/kg) | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.1 ± 0.04 | < 0.0001 |

| Midazolam dose administered in previous endoscopy1 (mean ± SD) | |||

| Initial (mg) | 3.78 ± 0.95 | 3.84 ± 1.04 | 0.7277 |

| Initial (mg/kg) | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.8448 |

| Total (mg) | 7.43 ± 2.79 | 7.4 ± 2.37 | 0.6087 |

| Total (mg/kg) | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.4360 |

| Δ Midazolam dose difference (total) (mg) | |||

| Median value (quartile 25%, 75%) | -2 (-3, 0) | -1 (-2, 1) | < 0.0001 |

| OR | 95%CI | P value1 | ||

| Age | 1.005 | 0.978 | 1.034 | 0.7025 |

| Female gender (vs male) | 1.521 | 0.731 | 3.164 | 0.262 |

| BMI | 1.072 | 0.992 | 1.158 | 0.0797 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Ex-smoker (vs never smoker) | 1.07 | 0.484 | 2.366 | 0.8673 |

| Current smoker (vs never smoker) | 1.311 | 0.572 | 3.007 | 0.522 |

| Alcohol | ||||

| Moderate (vs none to minimal) | 1.283 | 0.683 | 2.409 | 0.438 |

| Heavy (vs none to minimal) | 0.925 | 0.413 | 2.075 | 0.8504 |

| Medication2: Yes (vs no) | 1.055 | 0.242 | 4.598 | 0.9436 |

| Endoscope type: H260 (vs H290) | 1.405 | 0.854 | 2.312 | 0.1808 |

| Endoscopist experience | ||||

| Expert (vs less experienced) | 0.712 | 0.403 | 1.256 | 0.2407 |

| Highly expert (vs less experienced) | 0.822 | 0.434 | 1.557 | 0.5477 |

| Δ Midazolam dose difference (total) (mg) | 1.213 | 1.099 | 1.338 | 0.0001 |

In this study, we investigated the recurrence rate of paradoxical reactions occurring during upper endoscopy under midazolam sedation and showed that a high dose of midazolam was a risk factor for recurrent paradoxical reactions. Paradoxical reactions recurred in 30.7% of participants who had previously experienced paradoxical reactions to midazolam during upper endoscopy. Our study showed that the incidence of paradoxical reactions was higher in participants who had previously experienced paradoxical reaction than in 1.51% of the general population. Thus, sedatives should be used with care in patients with previous paradoxical reactions to midazolam.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the recurrence rate of paradoxical reactions to midazolam during upper endoscopy under sedation. In Korea, upper endoscopy is recommended biennially for gastric cancer prevention in subjects aged > 40 years because of the high prevalence of gastric cancer. Therefore, many individuals have visited our health check-up center for repeated upper endoscopies annually or biennially according to their risk stratification for gastric cancer. By reviewing sedative endoscopy records and paradoxical reaction reports accumulated over 6 years, we evaluated the incidence of paradoxical reactions to midazolam as well as the recurrence rate in patients having undergone multiple endoscopies. The overall incidence reported here is 1.51% in the general population, which is similar to that reported in a previous study conducted in Korea (59/4140 patients, 1.4%)[8]. However, previous studies have reported very different incidence rates, ranging from 1% to 24%[10,11]. Because paradoxical reactions are mostly uncharacteristic, no defining diagnostic criteria have been established. Diagnosis therefore usually relies on the clinician’s subjective judgment. This leads to important differences in the reported incidence of paradoxical reactions defined by detailed behaviors. In our study, both attending physicians and nurses judged the occurrence of paradoxical reactions according to modified cooperation scores to compensate for ambiguous diagnostic limitations.

Our study showed that the total dose of midazolam administered was higher in the recurrent group (6.74 ± 2.58 mg) than in the non-recurrent group (5.49 ± 2.04 mg). However, during the previous sedative endoscopy in which all participants showed paradoxical reactions, there was no significant difference in the total dose of midazolam administered in the recurrent (7.4 ± 2.37 mg) and non-recurrent groups (7.43 ± 2.79 mg). Compared to the previous endoscopy, patients in both groups were administered a lower dose of midazolam. The median dose difference was 2 mg in the non-recurrent group and 1 mg in the recurrent group. In the multivariable analysis, this midazolam dose difference was significantly associated with recurrent paradoxical reactions. It has been suggested that recurrent paradoxical reactions to midazolam are dose-dependent. Similar to that reported here, previous studies reported that a higher dose of midazolam was an independent risk factor for paradoxical reactions[6,8]. Additionally, our study also showed that recurrent paradoxical reactions were dose-dependent. Therefore, the use of a lower dose of midazolam may help to reduce the recurrence of paradoxical reaction.

The mechanism of paradoxical reaction to midazolam is not yet fully understood. Several factors including age, gender, history of alcohol consumption, dose administrated, underlying emotional and psychiatric disorders, and genetic predisposition are thought to increase the risk of paradoxical reaction[6,8,12,13]. Notably, one study reported that identical twin men experienced similar paradoxical reactions[14]. Recently, Park et al[15] reported that genetic polymorphism of the multidrug resistance 1 gene was associated with plasma midazolam concentration and sedation grade after midazolam administration. These reports supported the genetic predisposition of paradoxical reactions.

Midazolam is known to act via gamma-amino-butyric acid (GABA), one of the main inhibitory neurotransmitters in the central nervous system[16]. Midazolam binds to GABAA receptors, increasing the influx of chloride ions into neurons and inhibiting depolarization, resulting in sedation[13]. Some patients may have genetic variability in the benzodiazepine-GABA-chloride receptor associated with multiple allelic forms, and thus experience an abnormal pharmacodynamic response[7,15]. Additionally, our study showed a high recurrence rate in participants with a history of paradoxical reactions, and it is suggested that this reaction may be related to genetic predisposing factors. Therefore, large-scale studies investigating various genetic factors are needed to elucidate the mechanism of paradoxical reactions.

Flumazenil is a selective GABAA receptor antagonist that acts as an antidote to benzodiazepines via competitive inhibition, particularly in cases of overdose[5]. Previous studies have reported the use of flumazenil to manage paradoxical reactions to midazolam[7,17]. In one study, procedures were successfully completed in 93.3% of cases among patients receiving flumazenil for paradoxical reactions[8]. Similarly, in our study, endoscopy was successfully completed in 23/26 participants (88.0%) who received flumazenil for recurring paradoxical reactions. Because paradoxical reactions are usually unpredictable, physicians should be prepared for prompt management with flumazenil.

Moderate sedation is recommend for routine endoscopy to achieve adequate anxiolysis, high satisfaction in both physicians and patients, and low risk of serious adverse events[18]. Although we aim for moderate sedation during endoscopy, many patients may achieve a lighter or deeper sedation level. Inadequate sedation may therefore be mistaken for a paradoxical reaction, and it is necessary to identify excessive behavior caused by pain or discomfort, and to check the state of con

This study has several limitations. First, this retrospective study might have selection bias as only 361/888 enrolled participants had a history of paradoxical reaction. We only evaluated risk factors for recurrent paradoxical reactions in upper endoscopy, excluding colonoscopy. Second, there is the possibility of a confounding bias owing to the retrospective nature of the study; however, we adjusted for potential confounders including age, sex, and alcohol consumption. Third, we classified the severity of paradoxical reactions as mild, moderate, or severe. However, the “paradoxical reaction report” only recorded moderate or severe cases. Therefore, the incidence of recurrent paradoxical reactions may have been underestimated as mild cases were not reported in this study. In addition, 17.4% of participants (155/888) were excluded because they underwent follow up endoscopy without sedation. This may also affect the recurrence rate of paradoxical reaction, allowing them to be underestimated. Fourth, we investigated lifestyle risk factors such as drinking and smoking via self-reported questionnaires, which may be subject to recall bias.

In conclusion, paradoxical reactions recurred in 30.7% of participants who experienced a paradoxical reaction to midazolam during a previous upper endoscopy. Multivariable analysis revealed that administration of a high dose of midazolam was a risk factor for recurrent paradoxical reactions. Therefore, sedatives should be used with caution in patients with previous paradoxical reactions to midazolam. Considering the high recurrence rate, it may be best to perform endoscopy without sedation. However, if the patient refuses or is anxious about the examination, the total dose of midazolam should be reduced by ≥ 2 mg compared to that administered previously. Because paradoxical reactions are usually unpredictable, physicians should be prepared for prompt management with flumazenil. Finally, large-scale prospective studies investigating genetic factors among others are needed to elucidate the mechanism of paradoxical reactions.

Some patients experience paradoxical reactions characterized by excessive movement or excitement during midazolam sedation.

Because paradoxical reactions of midazolam are specific to an individual, they are likely to recur on the next endoscopy. However, there are only a few studies on the recurrence of paradoxical reactions.

We investigated the recurrence rate and risk factors associated with recurrent paradoxical reactions. Our findings may be helpful when patients with a history of paradoxical reactions undergo endoscopy under sedation again.

We enrolled 361 patients with a history of paradoxical reactions during a sedative upper endoscopy. At a follow-up examination, patients with recurrent paradoxical reactions (recurrent group) and those without recurrence (non-recurrent group) were compared.

We report, for the first time, that the rate of recurrence of paradoxical reactions is significantly associated with the dose of midazolam administered.

To avoid the recurrence of such reactions, we recommend reducing the total dose of midazolam administered to patients with previous paradoxical reactions by ≥ 2 mg compared to the dose previously used.

Large-scale prospective studies investigating genetic factors are needed to elucidate the mechanisms of paradoxical reactions.

We acknowledge Jung GC, a biomedical statistician from the Healthcare Research Institute, Seoul National University Hospital Healthcare System Gangnam Center, for performing the statistical analyses in this study.

| 1. | Abraham NS, Fallone CA, Mayrand S, Huang J, Wieczorek P, Barkun AN. Sedation vs no sedation in the performance of diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a Canadian randomized controlled cost-outcome study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1692-1699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jin EH, Hong KS, Lee Y, Seo JY, Choi JM, Chun J, Kim SG, Kim JS, Jung HC. How to improve patient satisfaction during midazolam sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy? World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:1098-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Early DS, Lightdale JR, Vargo JJ 2nd, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Evans JA, Fisher DA, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH, Khashab MA, Muthusamy VR, Pasha SF, Saltzman JR, Shergill AK, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. Guidelines for sedation and anesthesia in GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:327-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 402] [Article Influence: 50.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu J, Liu X, Peng LP, Ji R, Liu C, Li YQ. Efficacy and safety of intravenous lidocaine in propofol-based sedation for ERCP procedures: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:293-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Whitwam JG, Amrein R. Pharmacology of flumazenil. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand Suppl. 1995;108:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shin YH, Kim MH, Lee JJ, Choi SJ, Gwak MS, Lee AR, Park MN, Joo HS, Choi JH. The effect of midazolam dose and age on the paradoxical midazolam reaction in Korean pediatric patients. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;65:9-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mancuso CE, Tanzi MG, Gabay M. Paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines: literature review and treatment options. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:1177-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tae CH, Kang KJ, Min BH, Ahn JH, Kim S, Lee JH, Rhee PL, Kim JJ. Paradoxical reaction to midazolam in patients undergoing endoscopy under sedation: Incidence, risk factors and the effect of flumazenil. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:710-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ng JM, Kong CF, Nyam D. Patient-controlled sedation with propofol for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yi SY, Shin JE. Midazolam for patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a prospective, single-blind and randomized study to determine the appropriate amount and time of initiation of endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1873-1879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Massanari M, Novitsky J, Reinstein LJ. Paradoxical reactions in children associated with midazolam use during endoscopy. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1997;36:681-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kirkpatrick D, Smith T, Kerfeld M, Ramsdell T, Sadiq H, Sharma A. Paradoxical Reaction to Alprazolam in an Elderly Woman with a History of Anxiety, Mood Disorders, and Hypothyroidism. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016;2016:6748947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moallemy A, Teshnizi SH, Mohseni M. The injection rate of intravenous midazolam significantly influences the occurrence of paradoxical reaction in pediatric patients. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19:965-969. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Short TG, Forrest P, Galletly DC. Paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines--a genetically determined phenomenon? Anaesth Intensive Care. 1987;15:330-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Park JY, Kim BJ, Lee SW, Kang H, Kim JW, Jang IJ, Kim JG. Influence of midazolam-related genetic polymorphism on conscious sedation during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in a Korean population. Sci Rep. 2019;9:16001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | van der Bijl P, Roelofse JA. Disinhibitory reactions to benzodiazepines: a review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:519-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fulton SA, Mullen KD. Completion of upper endoscopic procedures despite paradoxical reaction to midazolam: a role for flumazenil? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:809-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | McQuaid KR, Laine L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of moderate sedation for routine endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:910-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Nusrat S, Madhoun MF, Tierney WM. Use of diphenhydramine as an adjunctive sedative for colonoscopy in patients on chronic opioid therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88:695-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kamran M S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor:A P-Editor: Zhang YL