Published online Sep 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i27.8268

Peer-review started: June 13, 2021

First decision: June 25, 2021

Revised: July 6, 2021

Accepted: July 27, 2021

Article in press: July 27, 2021

Published online: September 26, 2021

Processing time: 94 Days and 17.3 Hours

Major hip surgery usually requires neuraxial or general anesthesia with tracheal intubation and may be supplemented with a nerve block to provide intraoperative and postoperative pain relief.

This report established that hip surgical procedures can be performed with a fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB) and monitored anesthesia care (MAC) while avoiding neuraxial or general anesthesia. This was a preliminary experience with two geriatric patients with hip fracture, American Society of Anesthesiologists status III, and with many comorbidities. Neither patient could be operated on within 48 h after admission. Both general anesthesia and neuraxial anesthesia were high-risk procedures and had contraindications. Hence, we chose nerve block combined with a small amount of sedation. Intraoperative analgesia was provided by single-injection ultrasound-guided FICB. Light intravenous sedation was added. Surgical exposure was satisfactory, and neither patient complained of any symptoms during the procedure.

This report showed that hip surgery for geriatric patients can be performed with FICB and MAC, although complications and contraindications are common. The anesthetic program was accompanied by stable respiratory and circulatory system responses and satisfactory analgesia while avoiding the adverse effects and problems associated with either neuraxial or general anesthesia.

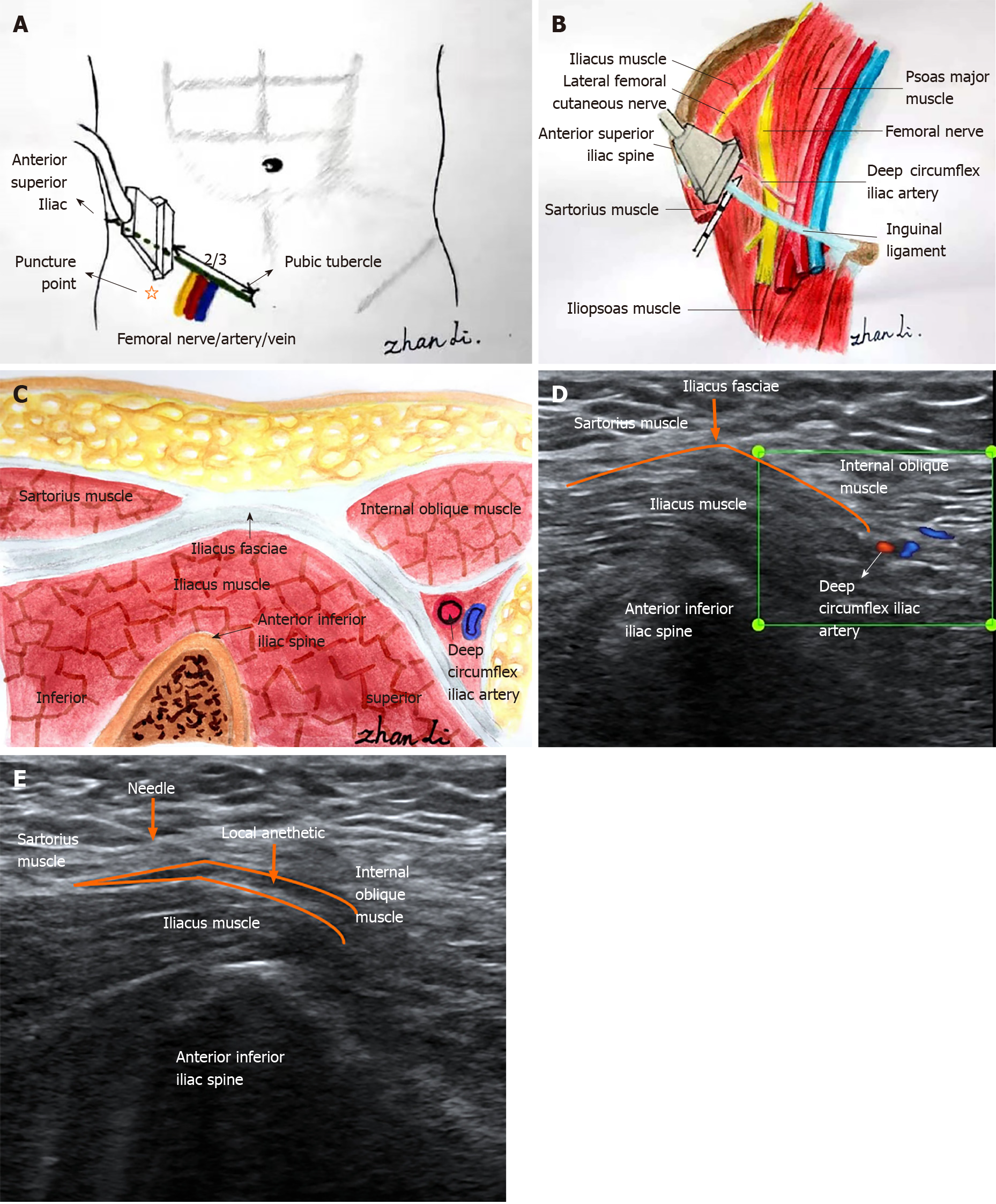

Core Tip: In clinical practice, we may encounter some elderly patients with many complications. As both general anesthesia and neuraxial anesthesia have high risks and contraindications, we chose nerve block combined with small amount of sedation. In this report, we describe administration of fascia iliaca compartment block in combination with low dose intravenous anesthesia to two geriatric patients, with satisfactory anesthetic effect. Anatomical diagrams and ultrasound imaging can, at a glance, promote this technique.

- Citation: Zhan L, Zhang YJ, Wang JX. Combined fascia iliaca compartment block and monitored anesthesia care for geriatric patients with hip fracture: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(27): 8268-8273

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i27/8268.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i27.8268

Hip fracture is a potentially devastating condition for older adults, and the primary mode of treatment is surgical repair. Evidence-based clinical practice in geriatric anesthesia shows a difference in mortality and postoperative complications depending on anesthesia techniques. A retrospective study of geriatric patients with hip fractures by Desai et al[1] concluded that regional anesthetic approaches are preferred to reduce all-cause readmission and in-hospital mortality. Regional anesthesia, especially peripheral nerve block, is the preferred method to achieve safe and effective anesthesia management[2].

Herein, we describe an alternative method, i.e. a combination of ultrasound-guided fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB) with monitored anesthesia care (MAC) as in two geriatric patients (Figure 1). Because of aging of the organs in the elderly, geriatric patients have a poor tolerance of surgery and an increased risk of perioperative complications of anesthesia. Contraindications have also been reported for general or neuraxial anesthesia, and attempts at using only nerve blockers for hip surgery have had poor effectiveness. Therefore, this anesthesia technique can serve as an alternative approach.

Case 1: The patient was admitted with severe left hip pain and limited activity 12 h after a fall.

Case 2: The patient was admitted with right hip swelling and pain with limited activity 2 d after a fall.

Case 1: Twelve hours before admission, the patient accidentally fell, with his left hip landing on the ground. He felt severe pain and swelling in his left hip and was unable to stand and walk. Therefore, he came to our hospital for an X-ray examination, which indicated a fracture of the proximal left femur. He was admitted to hospital for a left intertrochanteric femoral fracture. During the course of the disease, the patient had no disturbance of consciousness, no nausea and vomiting, no fever, no chest tightness, no dyspnea, and no gatism.

Case 2: The patient accidentally fell 2 d previously, and her right hip landed on the ground. At that time, she felt a slight pain in right hip and could not walk. The pain in the right hip did not improve after bed rest, so she came to our hospital for X-ray examination, which indicated fracture of the right femoral neck. She was admitted to hospital for a right femoral neck fracture. During the course of the disease, the patient was lucid, without coma, dizziness, headache, chest tightness, dyspnea, gatism, and no recent significant change in weight.

Case 1: He had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for 20 years.

Case 2: She had a history of cerebral infarction 5 years previously, but no sequelae after treatment. Hypertension and diabetes were also present in the patient for years; they were addressed by self-medication and a normal control routine.

Cases 1 and 2: There was no history of smoking, drinking, or drug abuse. The parents were deceased; a family genetic history was denied.

Case 1: The patient was lucid and had a painful expression. The patient was pushed into the ward on a flat gurney. His blood pressure was 127/78 mmHg, he cooperated with the physical examination and his answers were relevant. No yellow staining was found in the sclera, the superficial lymph nodes were not enlarged, the respiratory sounds in both lungs were rough, his heart rate was 96 beats/min, harmonized, and a systolic murmur could be heard at the apex. Abdominal tenderness, no obvious tenderness and rebound pain were found. Specialized examination revealed physiological spinal curvature, no obvious spinous process or paravertebral tenderness, the pelvic compression separation test was negative. The left hip was swollen, local tenderness was positive, and the left lower limb flexion and external rotation reached 90 degrees. The left lower limb was 1 cm shorter than the opposite side, the peripheral blood flow and feeling in both lower limbs were normal, and the foot dorsal artery was accessible.

Case 2: The patient was lucid and appeared to be in pain. She was moved into the ward in a wheelchair. The head form was normal, bilateral pupils showed large, equal circles sensitive to light reflection. The abdomen was soft, with no tenderness and rebound pain. A specialized examination revealed physiological bending of the spine, no obvious spinous process and paravertebral tenderness, the chest compression and pelvic compression tests were negative. There was hip swelling, short contraction spin deformity of the right lower limb, right groin area tenderness (+), right "four" word test (+), peripheral blood flow and feeling in both lower limbs were normal, and the foot dorsal artery was accessible.

Case 1: The most recent laboratory examination before surgery showed that the level of brain natriuretic peptide was 1253.50 pg/mL and that D-dimer was 3.88 μg/mL.

Case 2: The hemoglobin level was 62 g/L. After the infusion of three units of packed red blood cells, the hemoglobin level rose to 82 g/L.

Case 1: The ejection fraction was 42%. The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed frequent premature ventricular contractions. Color Doppler ultrasound suggested the occurrence of thrombosis in the lower femoral vein and popliteal vein of the left lower extremity.

Case 2: The ECG showed atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular rate.

The final diagnosis of the presented cases was hip fracture.

The anesthesia program was FICB combined with MAC.

This anesthesia method met the surgical needs and neither patient complained of any symptoms during the procedure.

As both patients also had a variety of severe diseases, COPD for 20 years and frequent premature ventricular contractions in case 1, and anemia and atrial fibrillation in case 2, regional anesthesia was scheduled. Antiplatelet therapy precluded neuraxial anesthesia and deep regional nerve block, such as parasacral sciatic nerve or paravertebral lumbar plexus block.

The hip joint and its muscles are innervated by the lumbar and sacral plexuses[3], and most nerve roots of interest are in the L2–L4 region of the lumbar plexus[4]. The anterior aspect of the hip capsule is densely innervated, suggesting that periarticular infiltration of the area plays a vital role in reducing perioperative pain during hip surgery. Thus, FICB is considered an anterior approach of the lumbar plexus[5] and is thought to block most nerves during hip surgery; some other nerves should also be blocked for complete anesthesia in hip surgery. The anesthesia can be effectuated by intravenous drugs. Sedation anesthesia was indispensable for the safe and effective placement of the FICB in the two patients. The physiology of geriatric patients causes pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes that should be considered when planning and providing anesthetic care. The increased sensitivity is multifactorial and related to changes in metabolism that occur with normal physiological aging and changes in drug bioavailability and distribution[6]. We thus administered FICB combined with low dose MAC to the two geriatric patients. The technique involved the administration of balanced anesthesia without an endotracheal tube or laryngeal mask. In case 1, we attempted the anesthesia scheme and prepared the required materials for the tracheal cannula as required. When the operation began, we found that the approach was suitable for proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA) surgical anesthesia without endotracheal intubation. As this type of anesthesia can be used for PFNA surgery, it was used for total hip arthroplasty in case 2, although the surgical wound had a large area, and the procedure required a prolonged duration. A satisfactory anesthetic effect was achieved.

Based on general consensus, frailty is defined as a clinical state in older patients with an increased vulnerability of multiple organ systems, compromised ability to respond to stressors, and negative outcomes[7]. Because of the vulnerability of geriatric patients, regional anesthesia administered carefully has significant benefits, such as hemodynamic stability, less deep vein thrombosis, increased postoperative cognition, fewer adverse effects from systemic pain medications, and a decrease in polypharmacy interactions[8]. Ultrasound-guided FICB is an optimal approach for hip surgery because of the relative ease of administration and reduced pain triggered by changes in posture[9].

Intriguingly, this anesthetic technique has been used for routine hip surgery in geriatric patients with debilitating comorbidities[10]. Drugs and instruments prepared for tracheal intubation in emergency cases were used. In that clinical study, geriatric patients in whom FICB combined with low dose MAC did not meet the surgical needs, intubation was performed under general anesthesia. Because FICB had been carried out, the general anesthetic and intraoperative blood loss were decreased, postoperative deep vein thrombosis was prevented, and the incidence of postoperative delirium, nausea, vomiting, regional pain syndrome, and cardiovascular complications were reduced[10].

Improving trends in global health care have led to a steady increase of the geriatric population. If hip surgery patients have contraindications of neuraxial anesthesia and general anesthesia, a combination of ultrasound-guided FICB with MAC is an alternative for patients that has a stable perioperative period and improved quality of life. Herein, we reported our experience with two patients, and their cases can be used for reference by other anesthesiologists.

| 1. | Desai V, Chan PH, Prentice HA, Zohman GL, Diekmann GR, Maletis GB, Fasig BH, Diaz D, Chung E, Qiu C. Is Anesthesia Technique Associated With a Higher Risk of Mortality or Complications Within 90 Days of Surgery for Geriatric Patients With Hip Fractures? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476:1178-1188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Perlas A, Chan VW, Beattie S. Anesthesia Technique and Mortality after Total Hip or Knee Arthroplasty: A Retrospective, Propensity Score-matched Cohort Study. Anesthesiology. 2016;125:724-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ke X, Li J, Liu Y, Wu X, Mei W. Surgical anesthesia with a combination of T12 paravertebral block and lumbar plexus, sacral plexus block for hip replacement in ankylosing spondylitis: CARE-compliant 4 case reports. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17:86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Amin NH, Hutchinson HL, Sanzone AG. Infiltration Techniques for Local Infiltration Analgesia With Liposomal Bupivacaine in Extracapsular and Intracapsular Hip Fracture Surgery: Expert Panel Opinion. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32 Suppl 2:S5-S10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Desmet M, Vermeylen K, Van Herreweghe I, Carlier L, Soetens F, Lambrecht S, Croes K, Pottel H, Van de Velde M. A Longitudinal Supra-Inguinal Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block Reduces Morphine Consumption After Total Hip Arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42:327-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lin C, Darling C, Tsui BCH. Practical Regional Anesthesia Guide for Elderly Patients. Drugs Aging. 2019;36:213-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shem Tov L, Matot I. Frailty and anesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017;30:409-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Scurrah A, Shiner CT, Stevens JA, Faux SG. Regional nerve blockade for early analgesic management of elderly patients with hip fracture - a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2018;73:769-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yu B, He M, Cai GY, Zou TX, Zhang N. Ultrasound-guided continuous femoral nerve block vs continuous fascia iliaca compartment block for hip replacement in the elderly: A randomized controlled clinical trial (CONSORT). Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Perrier V, Julliac B, Lelias A, Morel N, Dabadie P, Sztark F. [Influence of the fascia iliaca compartment block on postoperative cognitive status in the elderly]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2010;29:283-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Iida H S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Guo X