Published online Aug 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i24.7062

Peer-review started: April 1, 2021

First decision: April 28, 2021

Revised: May 12, 2021

Accepted: July 6, 2021

Article in press: July 6, 2021

Published online: August 26, 2021

Processing time: 144 Days and 13.2 Hours

Preterm birth is on the rise worldwide. Neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) have enabled many critically ill newborns to survive. When a premature baby is admitted to the NICU, the mother–infant relationship may be interrupted, affecting the mother's mental health.

To examine the maternal emotions associated with having a child in the NICU and provide suggestions for clinical practice.

MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsychARTICLES, and PsychINFO were searched for relevant articles between 2005 to 2019, and six qualitative articles were chosen that explored the experiences of mothers who had a preterm infant in the NICU. The thematic analysis method was used to identify the most common themes.

Four main themes of the experience of mothers who had a preterm infant in the NICU were identified: Negative emotional impacts on the mother, support, barriers to parenting, and establishment of a loving relationship.

NICU environment is not conducive to mother-child bonding, but we stipulate steps that health care professionals can take to reduce the negative emotional toll on mothers of NICU babies.

Core Tip: Mothers had negative experiences when their premature infants were hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care units (NICU). These experiences are related to such factors as the condition of the infant and the NICU environment. Maternal emotions included shock, feelings of unpreparedness, fear, anxiety, and guilt, and nurses play a significant role in helping the mothers. With the help of family members, health care professionals, and religious beliefs, the mothers also had positive experiences and established loving relationships with their babies. Doctors and nurses in the NICU with appropriate social skills can help parents better understand their child’s condition, potential treatment plans, and prognosis.

- Citation: Wang LL, Ma JJ, Meng HH, Zhou J. Mothers’ experiences of neonatal intensive care: A systematic review and implications for clinical practice. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(24): 7062-7072

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i24/7062.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i24.7062

Premature births are on the rise worldwide and account for > 11% of live births annually[1]. The cause of premature delivery, either spontaneous or provider-initiated (i.e. Cesarean section) varies widely, and premature delivery may contribute to lifelong disabilities, including learning delays, somatosensory problems, and increased risk of chronic disease[2]. Preterm birth complications account for approximately 35% of neonate deaths[3] and are one of the largest single factors of global disease analysis burden due to their high mortality and risk of lifelong damage[4]. The unexpected birth of a premature infant can be shocking to the family[5] and take an emotional toll on the mother and father, particularly if complications accompany the delivery. Although current technology within neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) enables many neonates in critical condition to survive[6], several studies have suggested that the frequent invasive procedures and unpleasant environmental factors may be detrimental to both the newborn’s development[7-9] and the mother’s emotional state[10]. Indeed, preterm birth has lasting impacts on the mother’s well-being and early relationship with her infant[5]: When preterm infants are admitted to the NICU, mother-infant bonding is interrupted and results in delayed progress to the relationship formation[11]. Incubation inhibits the early development of regulatory processes (e.g., stress response) and often leads to alienation between mother and child, further exacerbating the negative emotions of the mother[10]. The psychological trauma experienced by mothers of premature infants can last for months or years after NICU discharge[12] and may permanently alter the relationship between mother and child without appropriate intervention.

Many studies on NICU babies have demonstrated the importance of active parent involvement on long-term outcomes of the family unit[13]. Early mother-infant mutual bonding helps promote the development of the infant and fortifies the mother’s physical and emotional well-being. Furthermore, the active participation of parents in their child’s NICU care has been shown to improve infant weight gain[14], shorten the length of NICU stay[15], and improve overall health outcomes[16]. The current review seeks to evaluate the emotional response of mothers after preterm delivery of a baby and suggests modifications of clinical practice to address better these experiences.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement guided the research presented in this review.

We searched for all relevant studies published between January 1, 2008, and June 28, 2019 using the following databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsychARTICLES, and PsychINFO. Terms used in the search followed the “Population-Exposure-Outcome” (PEO) framework and included: “Mother OR Maternal OR Parent OR Stepmother OR Motherhood”, “Premature Infant/baby/neonate/newborn/birth/child OR Low birth weight infant/neonate”, “NICU, Pediatric ICU/Intensive Care/Critical Care/ Intensive Therapy Unit”, and “Experience OR Perception OR Perspective OR View OR Needs”. The search strategy utilized free text searching and was limited to studies published in the English language. We also conducted a grey literature search and manual search of bibliographic references from empirical articles to reduce the possibility of omitting relevant research.

Using the PEO framework, we identified inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria based on population, exposure, and outcome, respectively, as follows: (1) Studies that identified more than or equal to six mothers who had a live, premature infant born before 37 wk gestation; (2) Studies in which the premature infant was monitored in the NICU for > 1 wk; this is because it is easier for mothers to have negative emotions when the infants stayed more than 1 wk in the NICU; and (3) Studies that provided narrative descriptions of the mothers’ experiences of having a preterm infant in the NICU.

(1) Studies that identified mothers who did not have a live, premature infant born before 37 wk gestation; (2) Studies in which the premature infant was monitored in the NICU for < 1 wk; and (3) Studies that provided active descriptions of the mothers’ experiences of having a preterm infant in the NICU. Since we aimed to evaluate qualitative empirical articles, studies that utilized survey data were excluded.

A single researcher conducted the selection of studies in three phases. In the first phase, the investigator reviewed titles and abstracts for information relevant to the inclusion criteria. In the second phase, the same investigator thoroughly read and evaluated each of the articles identified in the first phase to determine the list of final studies to be included in this systemic review. During the final phase, to reduce selection bias, the investigator utilized the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist to assess each article for specific strengths and weaknesses associated with the review question.

Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, we utilized the four stages of a narrative synthesis approach[17] to identify key findings: (1) Developed a preliminary synthesis; (2) Explored the relationships within and between the included studies; (3) Assessed the “robustness” of each study; and (4) Integrated and compared categories to identify common themes.

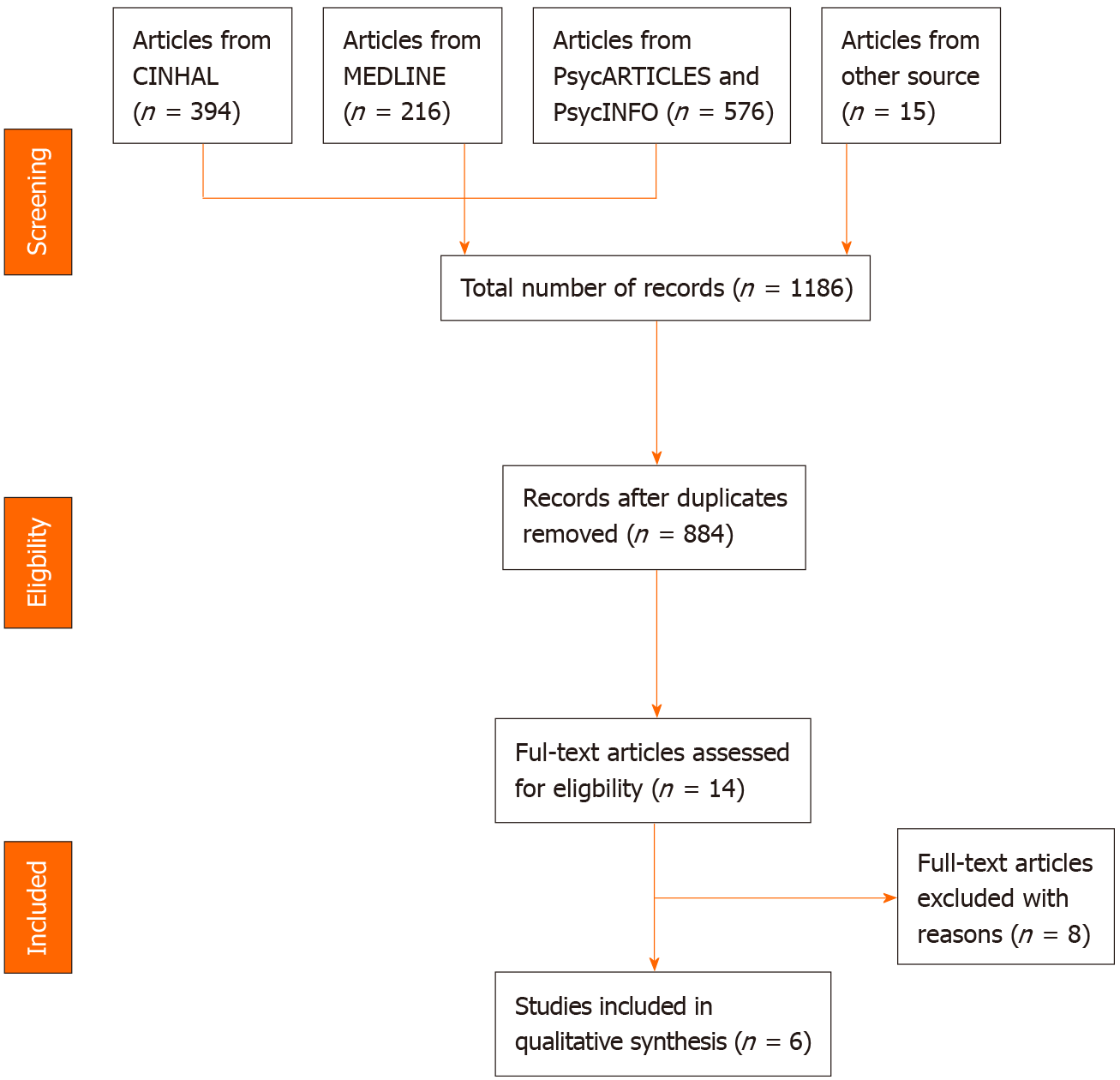

Of the 1186 articles identified in the initial database search, we identified 884 that corresponded with our search terms. The titles and abstracts of these were evaluated, and 14 studies that focused on the experiences of mothers with premature infants in the NICU was set aside for full-text analysis; six met the inclusion criteria and are discussed in this review (Figure 1).

The six studies identified as exploring the mothers’ experience of having a premature infant in the NICU were all conducted in different countries (Iran[10], Northern Sweden[18], Taiwan[19], Jordan[20], South Africa[21], and Spain[22]; Table 1). The number of participants in each study ranged from 6 to 26 and included women between the ages of 19 to 42. Gestational age of the infants ranged 25-34 wk, and time spent in the NICU was < 30 d. While all of the studies were identified as descriptive qualitative studies and relied predominately on individual in-depth interviews, the data analysis methodology differed for each: Three used phenomenological methods[10,20,22]; two used content or comparison analysis[18,19]; and one used Tesch’s method of analyzing qualitative data[21].

| Ref. | Design/data collection/data analysis | Population studied (P)/exposure (E) | Sample selection | Outcomes |

| Malakouti et al[10], Iran | Descriptive qualitative study; Individual semi-structured interviews; Phenomenological method (Colaizzi’s) | P: 20 mothers (19-37 yr) with average socioeconomic status in a NICU. No data on infants provided | - | Four main themes: (1) Sense of alienation; (2) Lack of control; (3) Care; and (4) Deprivation |

| Lindberg and Öhrling[18], Northern Sweden | Descriptive qualitative study; Narrative interviews; Content analysis | P: 6 mothers (25-35 yr); infants GA 28-34 w.E: The infants were cared for at the NICU for at least 1 wk | Purpose sample | The content analysis resulted in five categories: (1) Being a mother without being prepared; (2) Being in a situation filled with anxiety; (3) Struggling to feel close to the infant; (4) Effects on family life; (5) Being able to handle the situation |

| Lee et al[19], Taiwan | Qualitative research, ground theory; In-depth interviews and participant observations; Comparison analysis | P: 26 mothers (22-36 yr); infants GA 25-34 w, BW 530-1490 gE: The infants remained in NICU for periods of 32-120 d | - | The paradigm model comprising: (1) Casual conditions; (2) Context; (3) Intervening conditions; (4) Action/interaction strategies; and (5) Consequences |

| Obeidat and Callister[20], Jordan | Descriptive qualitative study; Individual open-ended interviews; Phenomenological method (Colaizzi’s) | P: 20 Muslim mothers (25-42 yr); Infants born before GA 28-34 w.E: The infants were hospitalized in NICU for at least 1 wk | - | Four main themes: (1) Feeling emotional instability; (2) Living with challenges in observance; (3) Finding strength through spiritual beliefs; and (4) Trying to normalize life |

| Khoza and Ntswane-Lebang[21], Africa | Descriptive qualitative study; Individual in-depth interviews; Tesch’s method of analyzing qualitative data | P: 13 mothers (15-31 yr) for at least 1 wk. No data on infants provided | - | Five major categories: (1) Emotions; (2) Subjective suffering; (3) Support; (4) desperate wishes; and (5) Expressed needs |

| Fernández Medina et al[22], London | Interpretive qualitative research; In-depth, semi-structured interviews; Gadamer's hermeneutic phenomenology | P: 16 mothers (> 18 yr); infants mean GA 25.9 w.E: The infants were hospitalized in NICU for at least 30 d | Convenience sampling | Two main themes: (1) Negative emotional impact; and (2) Learning to be a mother |

We utilized a thematic analysis technique to extract, code, organize, and report key themes from the individual studies. Four key themes were identified: “Negative emotional impact on the mother”, “Support”, “Barriers to parenting”, and “Establishing loving relationships with their baby” (Table 2).

| Ref. | The negative emotional impact on mother | Support | Barriers to parenting | Establishing loving relationships with their baby | ||||

| Shock and unpreparedness | Fear and anxiety | Guilt | Support from religious or spiritual beliefs | Support from family members | Support from health professionals | |||

| Lindberg and Öhrling[18], Northern Sweden | √ | √ | ||||||

| Khoza and Ntswane-Lebang[21], Africa | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Lee et al[19], Taiwan | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Malakouti et al[10], Iran | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Obeidat and Callister[20], Jordan | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Fernández Medina et al[22], London | √ | √ | √ | |||||

The arrival of negative emotions that inundate parents upon learning their child will be admitted to the NICU has been well documented[23,24]: Worry, shock, and anxiety are just several emotions that may cloud the joy many mothers experience upon childbirth. All six studies in this review also identified negative emotional experiences, specifically of the mother, after their infant was admitted to the NICU. Three sub-themes were identified: “Shock and unpreparedness”, “Fear and anxiety”, and “Guilt” (Table 2).

The expectation of giving birth to a healthy baby often accompanies a woman’s pregnancy journey. This expectation is understandably fractured upon the delivery of a premature infant. Three studies included in this review reported that mothers experienced shock and unpreparedness when they delivered a premature infant who required NICU care[18,19,21], particularly upon seeing their small stature and learning of unexpected medical complications.

Four studies reported that mothers experienced fear and anxiety during their premature infant’s stay in the NICU[10,20-22]. The sense of fear, while persistent, transitioned from fear due to small size[10] to fear of losing their baby[21,22] as time spent in the NICU increased. Furthermore, all six studies reported a sense of anxiety in the mothers as they worried about their baby’s life expectancy, future health conditions, and potential medical complications[10,18-22].

Three studies described mothers’ sense of guilt upon learning their premature infant would be admitted to the NICU[10,20,22]. The narrative synthesis approach utilized by each study allowed for the dissection of this guilt – immediately after birth, the mothers appeared to blame themselves for the premature arrival of their child and wondered if particular actions they took (e.g., working too hard; taking certain medications) led to the early delivery[10,22]. However, as time passed, the mothers’ guilt was due more to perceived negligence[10] and the inability to “…keep him inside me longer…” as if to protect the baby through the full pregnancy term[22].

During pregnancy and after childbirth, the support of family and medical professionals is often paramount in the healthy development of the mother-child bond. Three sub-themes were identified in these qualitative studies: “Support from religious or spiritual beliefs”, “support from family members”, and “support from health professionals”.

Three studies reported the importance of mothers’ belief system during their time forming a relationship with their new baby in the NICU[19-21]. The mothers expressed feelings of “hope” and “comfort” at the thought of a higher power (e.g., God[19,21]; ancestors[20]) looking over and protecting their baby from continued hardship. Notably, mothers appealed to the higher powers for both themselves and their baby, asking for guidance and courage to manage caring for a premature, often medically compromised infant.

Lee et al[19] and Khoza and Ntswane-Lebang[21] reported the importance of family in the mothers’ inner support circle. Each mother questioned in these two studies identified their husbands as critical supporters during the time their child was in the NICU[19,21]. Maternal and paternal grandmothers provided additional support, particularly during the immediate postpartum period.

Finally, two studies reported critical support, specifically from health care professionals[10,19]. Doctors and nurses alike provided information about the infants’ medical conditions and course of treatment; nurses, however, provided additional emotional support[19]. Physical support often accompanied the verbal support from the nurses, and mothers reported a sense of gratitude when nurses helped care for their newborns[10]. Informational support was also made available in several cases by social workers relaying information about financial aspects and what to expect upon discharge[19].

Four studies reported the difficult experience mothers had in forming relationship with their babies while in the NICU environment[10,18,19,22]. Most often, the mothers appeared wary of the infants’ physical appearance and small size; this resulted in apprehension to physically touch, feed, and otherwise nourish their baby[10,19,22]. Fear of further hurting their babies also accompanied the mothers’ apprehension[10] and cyclically affected feelings of fear and anxiety. The physical separation between mother and baby was also noted as a critical obstacle in the formation of mother-child relationships. In situations where babies were confined to incubators, the mothers reported feelings of alienation[18,22] and found it difficult to overcome the physical plastic barrier. Lee et al[19] also noted that maternal conditions affected the mother’s ability to bond immediately with her child: first-time mothers often lacked the knowledge required to care for their babies properly, and therefore found it difficult to nurture. Furthermore, medical complications in the mother (e.g., high-risk pregnancy factors; Cesarean section) that accompanied the delivery made it particularly challenging for the mother to engage with her newborn while simultaneously healing herself[19].

These findings are supported by recent empirical studies that demonstrate a sense of loss in the mother when nurses take their baby and provide the majority of care[25,26]. Indeed, the bonding between mother and baby is naturally interrupted upon the baby’s admittance to the NICU: Skin-to-skin contact, which aids in physical, emotional, and social development[27], becomes rare or non-existent, further reducing necessary growth and development in both mother and child. However, several studies have reported the opposite: Heinemann et al[28] argued that some mothers enjoyed spending time in the NICU, as it allowed them to feel closer to the infant and observe and communicate with the medical staff. Notably, the NICU environment of each care facility may alter the mothers’ experiences: Warm reception by the nurses, soft lighting, and dampened noises, among other factors, may contribute to the mothers’ overall sense of calm, whereas harsher conditions have been shown to contribute to anxiety[10].

Four of the six studies reviewed described situations in which mothers reported developing a loving relationship with their child despite the challenging NICU environment[18-20,22]. Notably, the multiple avenues of support described above helped mothers overcome their fears and enabled them to manage their child’s care. In each scenario, the nurses proved crucial to the successful development of this bond, as they helped guide the mothers in routine care and provided information the mothers could use at home. This facilitated the transition of support from medical professionals to parents and consequently helped the mothers establish a loving relationship with their babies.

This finding is supported by other empirical research[26,29] demonstrating that mothers who actively engage in caring for their babies (e.g., breastfeed, provide skin-to-skin contact) ultimately establish loving relationships. Even those who express initial trepidation about handling their premature infant appear to transition from feelings of ambivalence to love over time[30].

The results of this systemic review highlight the negative experiences of mothers whose infants receive NICU care across six geographic locations. The inclusion of research from different countries is particularly important here: Results were consistent across the six studies, indicating that the identified themes are likely transferrable across race, religious affiliation, and location. The four major emotional themes identified, “Negative emotional impact on the mother”, “Support”, “Barriers to Parenting”, and “Establishment of loving relationships with baby” notably mirror several clinical comorbidities, including post-partum depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Indeed, mothers who deliver premature infants may display symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (i.e. reliving the traumatic event; severe emotional distress when reminded of the event) that can last months or years after the baby’s discharge[31]. Similarly, mothers may show symptoms of post-partum depression (depressed mood; difficulty bonding with baby; severe anxiety) during and after their baby’s stay in the NICU[12].

Commonly cited maternal emotions including shock, feelings of unpreparedness, fear, anxiety, and guilt led to the development of three recommendations for clinical practice. As discussed, nurses play a significant role in helping mothers cope with challenges associated with NICU care. They provide physical and emotional front-line support to both mother and baby and provide crucial informational resources for relationship development. Hence, the following recommendations for clinical practice surround NICU nursing care.

First, the development of universal practices to minimize the negative experiences of mothers should be initiated. These practices may include inviting the mother to participate in caring for her newborn, instructing on proper diapering, feeding, and bathing methods, and providing verbal explanations during procedures or medicinal administration. Indeed, actively and effectively involving the mothers in childcare will aid in the transition to motherhood, facilitate trust in the healthcare providers, and jumpstart the formation of a loving mother-child bond. Additionally, a family-centered approach[32] should be adopted by all medical providers in NICU settings, and the continued development of appropriate social skills by doctors and nurses in the NICU would help parents better understand their child’s condition, potential treatment plans, and eventual prognosis. Indeed, the clear, concise presentation of these variables is important when communicating with mothers of premature infants, particularly given already heightened situational fear and anxiety. Finally, the authors recommend that NICU staff participate in regular intra-departmental dialogue to understand better the experiences of NICU mothers and develop appropriate clinical practice that aligns with societal and nursing standards.

Future qualitative research should explore the continued development of supportive care in the NICU and the subsequent experiences of mothers utilizing family-centered care. Family-centered care is gaining traction worldwide[32,33], and future studies will aid our understanding of the benefits and potential pitfalls of this approach. Additionally, many studies have explored the experiences of fathers and mothers who have a child in the NICU but few have addressed broader family experiences. Interviews with siblings, grandparents, extended family members, and community members of the family would help in the development of mechanisms for support for both mother and child.

The limitations of this systemic review can be viewed in two groups: Limitations in the studies themselves and limitations to the systemic review process. In the first case, the most common limitation listed in the studies themselves was a failure to assess the importance of researcher-participant support. As noted, a well-rounded support system within the NICU was essential for helping mothers ultimately develop a loving bond with their children. If the primary interviewer in each of these studies was considered part of that support system, the mothers’ answers to the research questions may have been skewed. Furthermore, many of the participants in each of the six studies were from middle-class white families; the lack of diversity of the sample population likely skews the results. Finally, none of the studies mentioned in the current review included the duration of the newborn’s stay in the NICU. This factor naturally affects the mothers’ emotions and should be considered in subsequent empirical studies.

Limitations to the systemic review aspect of this research were also present. All six studies analyzed in this review were reported in the English language. Indeed, one of the largest barriers to this work was the limited translational resources: All non-English language studies were excluded, and mothers’ experiences may notably differ in regions where English does not predominate. Future systematic reviews of the current literature may aim to translate relevant studies from each language in an effort to include representative participants from all races, cultures, religions, and socioeconomic statuses. Similarly, the current search strategy did not include studies on indigenous minorities, and notable differences may be present in the experiences of indigenous minority mothers vs urban mothers in a NICU setting.

While this particular study evaluated the emotional component of having a child in the NICU, very little research exists on maternal physical health after delivery of a preterm infant. Future research may seek to highlight the connection between emotional and physical health in mothers and how this may affect child-rearing in the NICU environment. Finally, this review focused solely on research available on mothers whose children survived after NICU admittance; families whose infants died in NICU care may be less likely to participate in research studies, further skewing the results.

We conclude that the NICU is not conducive to the formation of a mother-child bond, but a healthy bond can nevertheless be accomplished with the help of dedicated nursing staff who commit to altering standard NICU nursing practice to consider mothers’ emotions.

Worldwide, approximately 15 million infants are born each year prematurely. Complications due to premature birth is the largest direct cause of neonatal mortality and accounts for 35% of the global 3.1 million neonatal deaths each year. Mothers who have a preterm infant in the neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) often report significant negative experiences that may have far-reaching implications, although the full ramifications are not yet understood. The current review addresses this gap by systematically reviewing published articles aimed at evaluating mothers’ experiences when their infant is confined to the NICU.

Since there is no published qualitative systematic review in this area, it is necessary to explore the experiences of mothers who have a premature infant in the NICU. Notably, parents often report different experiences and responses when their preterm baby is in the NICU; usually, mothers experience more stress and other negative emotions compared with fathers.

The current study aimed to: (1) Explore mothers' experiences of having a premature baby in the NICU; (2) Identify the source of mothers' emotional stress; and (3) Provide recommendations for future research by identifying common themes in the relevant published literature.

A systematic and comprehensive electronic literature search was conducted using search terms relevant to NICU exposure and mothers’ stress. The “Population-Exposure-Outcome” framework was used to identify the inclusion and exclusion criteria based on population, exposure, study design, language, publication date, and study result. The selection of studies followed two phases: First, we determined whether the study was relevant to the current review questions and met inclusion criteria by reviewing the abstract. For relevant studies, we then analyzed the full paper for the determination of final inclusion. Finally, we utilized a narrative synthesis approach to identify key findings from each included study.

Four common themes emerged: (1) Negative emotional impact on the mother; (2) Support; (3) Barriers to parenting; and (4) Establishment of loving relationships between mother and baby.

Based on the literature review, the current study recommends that NICU staff actively involve mothers when taking care of their infants. This involvement will help the mothers in their transition to motherhood and support the well-being of infants and families alike.

Further qualitative research is needed to explore better and understand the experiences of mothers using family-centered care in the NICU. Furthermore, while this research is critical, there is still a need for research that identifies the experiences of family members when a premature infant is in the NICU, as this review focused on only the mothers' experience, and other members of the family may have different perspectives.

| 1. | Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, Adler A, Vera Garcia C, Rohde S, Say L, Lawn JE. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012;379:2162-2172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2858] [Cited by in RCA: 3183] [Article Influence: 227.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Magai DN, Karyotaki E, Mutua AM, Chongwo E, Nasambu C, Ssewanyana D, Newton CR, Koot HM, Abubakar A. Long-term outcomes of survivors of neonatal insults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0231947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McAllister DA, Liu L, Shi T, Chu Y, Reed C, Burrows J, Adeloye D, Rudan I, Black RE, Campbell H, Nair H. Global, regional, and national estimates of pneumonia morbidity and mortality in children younger than 5 years between 2000 and 2015: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e47-e57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 457] [Article Influence: 65.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bick D. Born too soon: the global issue of preterm birth. Midwifery. 2012;28:341-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Spinelli M, Poehlmann J, Bolt D. Predictors of parenting stress trajectories in premature infant-mother dyads. J Fam Psychol. 2013;27:873-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Santos LF, Souza IAd, Mutti CF, Santos NdSS, Oliveira LMdAC. Forces interfering in the mothering process in a neonatal intensive therapy unit. Texto Contexto-Enfermagem. 2017;26. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Valeri BO, Holsti L, Linhares MB. Neonatal pain and developmental outcomes in children born preterm: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:355-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schappin R, Wijnroks L, Uniken Venema MM, Jongmans MJ. Rethinking stress in parents of preterm infants: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aita M, Johnston C, Goulet C, Oberlander TF, Snider L. Intervention minimizing preterm infants' exposure to NICU light and noise. Clin Nurs Res. 2013;22:337-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Malakouti J, Jabraeeli M, Valizadeh S, Babapour J. Mother's experience of having a preterm infant in the neonatal intensive care unit: A phenomenological study. Iran J Crit Care Nurs. 2013;5:172-181. |

| 11. | Obeidat HM, Bond EA, Callister LC. The parental experience of having an infant in the newborn intensive care unit. J Perinat Educ. 2009;18:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Slomian J, Honvo G, Emonts P, Reginster JY, Bruyère O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Womens Health (Lond). 2019;15:1745506519844044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 657] [Article Influence: 109.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li XY, Lee S, Yu HF, Ye XY, Warre R, Liu XH, Liu JH. Breaking down barriers: enabling care-by-parent in neonatal intensive care units in China. World J Pediatr. 2017;13:144-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ding X, Zhu L, Zhang R, Wang L, Wang TT, Latour JM. Effects of family-centred care interventions on preterm infants and parents in neonatal intensive care units: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Aust Crit Care. 2019;32:63-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Segers E, Ockhuijsen H, Baarendse P, van Eerden I, van den Hoogen A. The impact of family centred care interventions in a neonatal or paediatric intensive care unit on parents' satisfaction and length of stay: A systematic review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019;50:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Greene J, Hibbard JH, Sacks R, Overton V, Parrotta CD. When patient activation levels change, health outcomes and costs change, too. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34:431-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 420] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N, Roen K, Duffy S. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme. Version 1. 2006. [cited 20 March 2021]. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Guidance-on-the-conduct-of-narrative-synthesis-in-A-Popay-Roberts/ed8b23836338f6fdea0cc55e161b0fc5805f9e27. |

| 18. | Lindberg B, Ohrling K. Experiences of having a prematurely born infant from the perspective of mothers in northern Sweden. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67:461-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee SN, Long A, Boore J. Taiwanese women's experiences of becoming a mother to a very-low-birth-weight preterm infant: a grounded theory study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:326-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Obeidat H, Callister L. The lived experience of Jordanian mothers with a preterm infant in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Neonatal-Perinatal Med. 2011;4:137-145. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Khoza S, Ntswane-Lebang M. Mothers' experiences of caring for very low birth weight premature infants in one public hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa. Africa J Nurs Midwifery. 2010;12:69-82. |

| 22. | Fernández Medina IM, Granero-Molina J, Fernández-Sola C, Hernández-Padilla JM, Camacho Ávila M, López Rodríguez MDM. Bonding in neonatal intensive care units: Experiences of extremely preterm infants' mothers. Women Birth. 2018;31:325-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Watson G. Parental liminality: a way of understanding the early experiences of parents who have a very preterm infant. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1462-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Al Maghaireh DF, Abdullah KL, Chan CM, Piaw CY, Al Kawafha MM. Systematic review of qualitative studies exploring parental experiences in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:2745-2756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Spinelli M, Frigerio A, Montali L, Fasolo M, Spada MS, Mangili G. 'I still have difficulties feeling like a mother': The transition to motherhood of preterm infants mothers. Psychol Health. 2016;31:184-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Moghaddam Tabrizi F, Alizadeh S, Radfar M. Barriers of parenting in mothers with a very low-birth-weight preterm infant, and their coping strategies: A qualitative study. Int J Pediatr. 2017;5:5597-5608. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N, Dowswell T. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;CD003519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Heinemann AB, Hellström-Westas L, Hedberg Nyqvist K. Factors affecting parents' presence with their extremely preterm infants in a neonatal intensive care room. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102:695-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Aagaard H, Hall EO. Mothers' experiences of having a preterm infant in the neonatal care unit: a meta-synthesis. J Pediatr Nurs. 2008;23:e26-e36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ncube RK, Barlow H, Mayers PM. A life uncertain - My baby's vulnerability: Mothers' lived experience of connection with their preterm infants in a Botswana neonatal intensive care unit. Curationis. 2016;39:e1-e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yaman S, Altay N. Posttraumatic stress and experiences of parents with a newborn in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Reproduct Infant Psychol. 2015;33:140-152. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dalvand H, Rassafiani M, Bagheri H. Family Centered Approach: A literature the review. J Modern Rehabilitat. 2014;8:1-9. |

| 33. | Lester BM, Miller RJ, Hawes K, Salisbury A, Bigsby R, Sullivan MC, Padbury JF. Infant neurobehavioral development. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35:8-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Nursing

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yang X S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH