Published online Aug 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6768

Peer-review started: November 5, 2020

First decision: December 13, 2020

Revised: December 26, 2020

Accepted: July 5, 2021

Article in press: July 5, 2021

Published online: August 16, 2021

Processing time: 273 Days and 0.1 Hours

Pylephlebitis is a rare condition, poorly recognized by clinicians and with few references. In this case, the clinical appearance resembled the clinical course of a pancreatic cancer and was originated by the ingestion of a fish bone, making the case more interesting and rare.

A 79-year-old female presented to the emergency department with fever, loss of appetite and jaundice. Tenderness in the right upper quadrant was present. Inflammation marker were high. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed gallstones and aspects compatible with acute pancreatitis. The patient was admitted to surgery ward and has her condition aggravated. A magnetic resonance revealed multifocal liver lesions. Later, a cholangiopancreatography and an endoscopic ultrasound (US) were able to diagnose the condition. Specific treatment was implemented and the patient made a complete recovery.

In conclusion, this case report demonstrates for the first time the diagnosis of an unusual case of pylephlebitis complicated by the migration of a fish bone, mimicking metastatic pancreatic cancer. Clinical presentation and traditional imaging studies, such as transabdominal US and CT, remain the standard for diagnosing this condition.

Core Tip: Pylephlebitis refers to septic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein or its branches, which is a rare and potentially lethal complication of an intra-abdominal infection. A female patient was studied clinical and imagiologically and was diagnosed with pylephlebitis arising from an infection of a fish bone migration. This condition is an extremely rare cause of pylephlebitis and, in this case, mimicked the clinic of a metastatic pancreatic cancer.

- Citation: Bezerra S, França NJ, Mineiro F, Capela G, Duarte C, Mendes AR. Pylephlebitis — a rare complication of a fish bone migration mimicking metastatic pancreatic cancer: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(23): 6768-6774

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i23/6768.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6768

Pylephlebitis refers to septic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein (PV) and/or its branches, and is considered a rare and serious complication of intra-abdominal infection[1]. It was Waller, in 1846, who discovered it during autopsy as a source of pyogenic intrahepatic abscesses[2]. Although pylephlebitis is a rare disease, mortality rates remain as high as 25%[3] due to its nonspecific symptoms that often delay the diagnosis. A fast diagnosis is essential to start treatment immediately.

The authors present an extremely rare and interesting case of pylephlebitis and subsequent pyogenic liver abscesses secondary to perforation and posterior migration of a fish bone.

The main complaints were a 7-d history of fever, weakness, decreased appetite and progressive jaundice with icteric conjunctiva.

A 79-year-old Caucasian female presented to our emergency department with a 7-d history of fever, weakness, decreased appetite and progressive jaundice with icteric conjunctiva. She denied nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain.

Her past medical history was remarkable for hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

Home medications include hydrochlorothiazide, losartan and simvastatin. She denied any family history of deep venous thrombosis, hypercoagulable states, known liver disease or risk factors for liver disease. There was no weight loss, bowel habits alteration or previous contact with sick individuals or recent travel.

The relevant findings of the physical examination were skin jaundice with icteric conjunctiva and tenderness in the right upper quadrant. There were no evidence of splenomegaly, ascites, peripheral edema or lymphadenopathy on physical exam

Laboratory results showed increased white blood cell counts 16.92 × 109/L and increased C-reactive protein 29.70 mg/L. Liver enzyme levels were elevated (aspartate aminotransferase 77 U/L; alanine aminotransferase 110 U/L; gamma-glutamyl transferase 325 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase 747 IU/L). Liver function was abnormal with total bilirubin (Tbrb) of 11.90 mg/dL. Creatinine (Cr) was elevated at 1.8 mg/dL. Serum amylase (Amy) was 216 U/L.

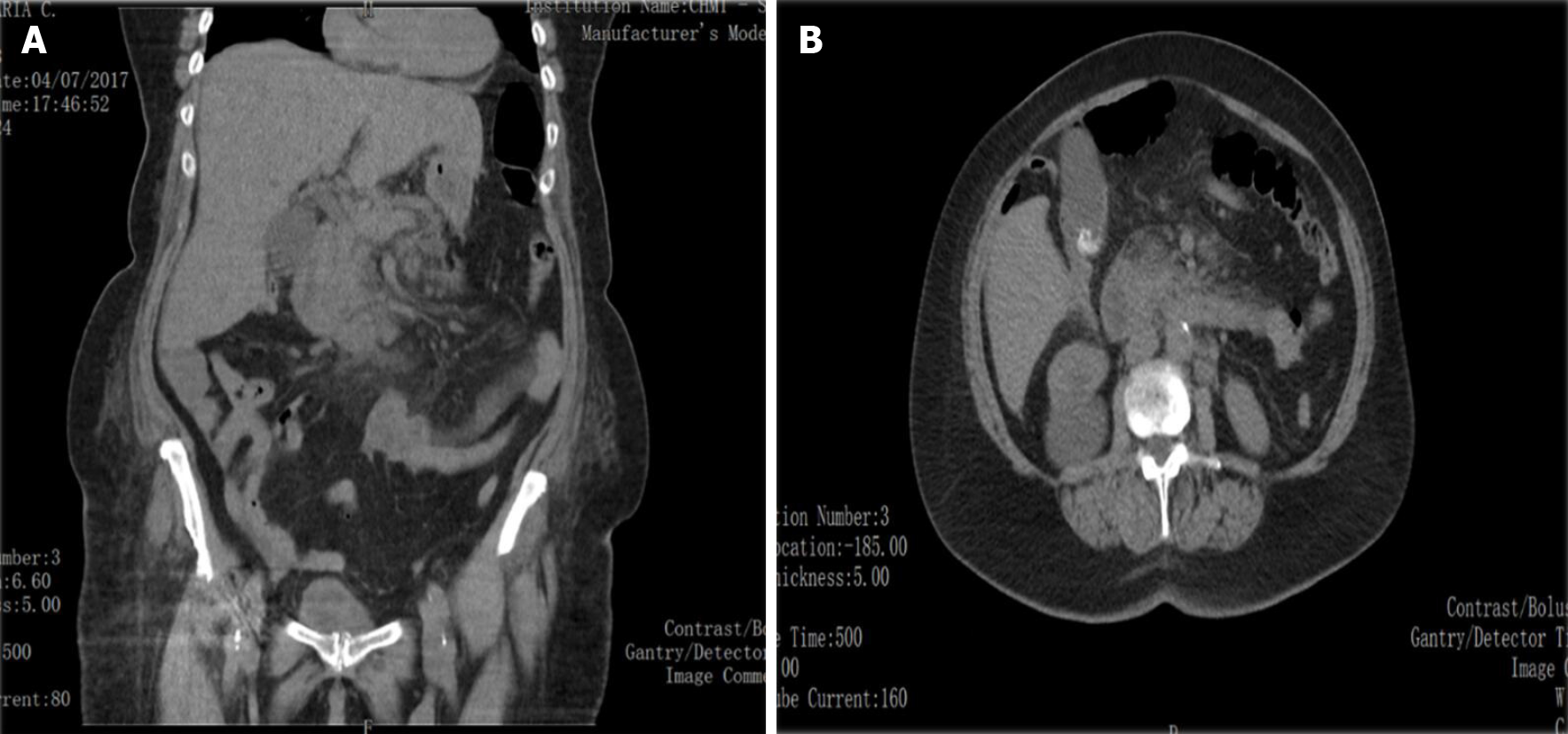

As there was no ultrasound (US) available in the Emergency Department, an abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan was conducted revealing minimum peritoneal leaking, gallstones with no biliary tract dilation and heterogeneous contour of the pancreas, with focal pancreatic fatty infiltration (Figure 1).

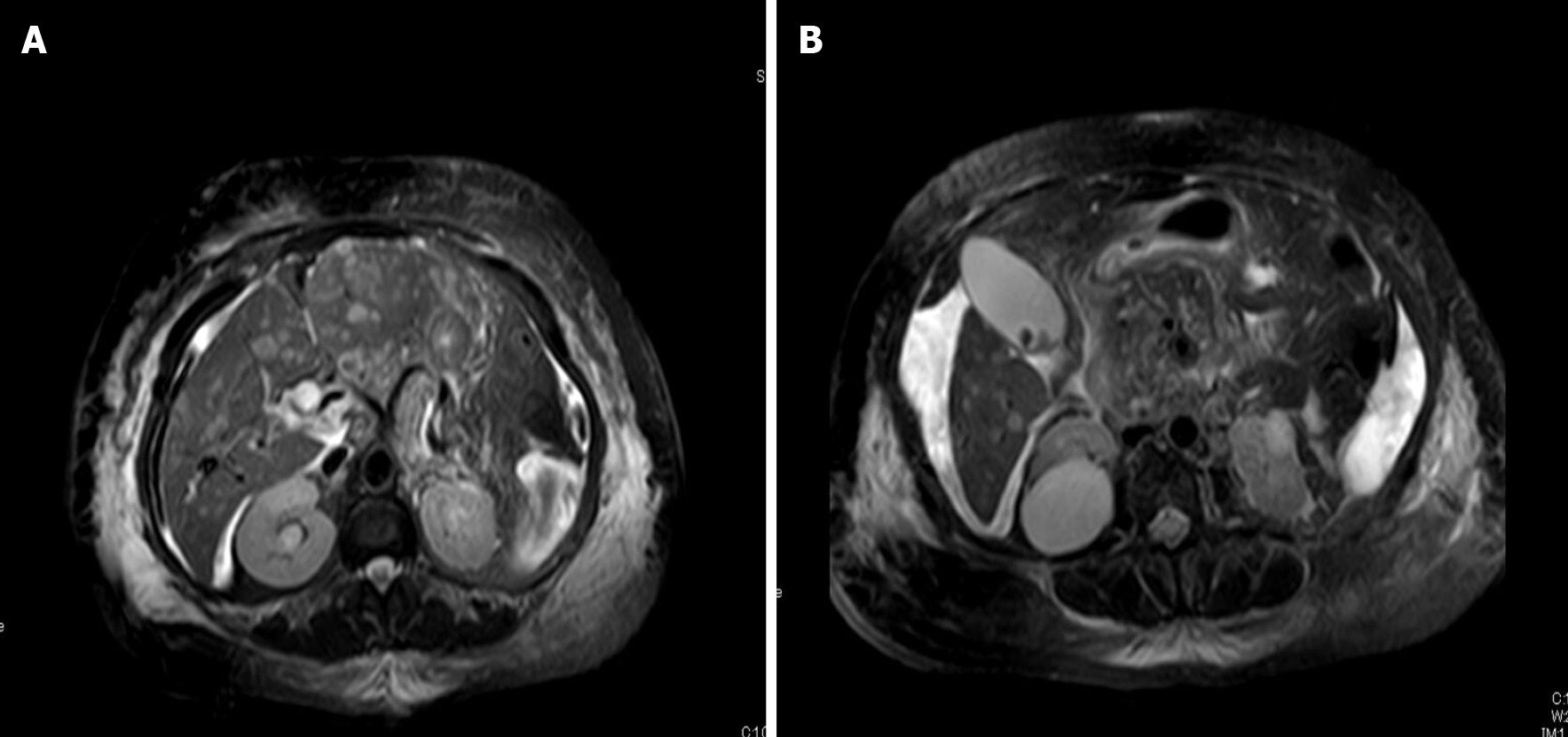

The patient was admitted to the hospital and observed; no antibiotics were administered. She persisted with skin jaundice, but no fever was registered. Considering the spectrum of elevated Tbrb, mainly direct bilirubin (Dbrb) levels, a magnetic resonance cholangiography was performed, which showed globosity of the head and uncinate process of the pancreas, with no notorious heterogeneity, associated with multifocal and multicentric altered pattern of liver parenchyma, mostly periportal, with suspicion of metastatic disease and stenosis of the distal main bile duct with dilation of the biliary tract to be further studied with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). At this point CEA levels were normal 2.09 ng/mL but elevated CA125 of 90.9 U/mL and CA19.9 of 59.2 U/mL were registered (Figure 2).

Suspecting neoplastic disease, the CT scan was repeated on hospital day 10, showing multiple hypodense liver lesions and heterogeneity of the pancreas head with nodular lesions. The intrahepatic duct and pancreatic duct were not dilated. The common bile duct showed 8-10-mm dilatation.

On day 14, an ERCP was performed. It showed distal common bile duct stenosis, suspicious of pancreatic head tumor with metastatic hepatic lesions, as shown in the CT study. However, the patient had no history of weight loss, along with improvement in cholestatic pattern, and these findings were against the hypothesis of neoplastic disease. Subsequently, the patient was evaluated with endoscopic US (EUS) for further pancreatic biopsy. The EUS showed thrombus within the main PV concerning an infected thrombophlebitis and left hepatic lobe with multiple lesions suggesting pyogenic liver abscesses, the larger one with a 5-cm diameter. An US-percutaneous guided biopsy of the left hepatic lesion was performed since a thin linear solid liver lesion was present.

The histology showed the finding of an intrahepatic abscess and a 6-mm filiform fragment, confirmed as a fish bone.

Infected thrombophlebitis resulting in pyogenic liver abscesses.

The findings of the case seemed as secondary to fish bone ingestion, perforating the gastrointestinal tract and migrating into the liver, resulting in pylephlebitis and multifocal hepatic abscesses. On retrospective inquiry, the patient confirmed ingestion of fish a few weeks prior. Blood cultures were conducted, and empiric antibiotic therapy was initiated with intravenous piperacillin and tazobactam, as well as anticoagulation. The antibiotic regimen was changed to ceftriaxone once the blood cultures were positive for Streptococcus intermedius.

The patient showed a dramatic improvement, and more than 1 mo later, the patient had clinical remission and was discharged with recommendation to take anticoagulation with Enoxaparin 60 mg for at least six months. She has been followed regularly at our medical center, with monotoration of her clinical condition.

Defined as infective suppurative thrombosis of the PV, pylephlebitis is an uncommon complication of intra-abdominal infections carrying significant morbidity and mortality. Firstly reported in 1846, when it was found on necropsy by Waller as the source of pyogenic liver abscess[2]. Starting with thrombophlebitis in the PV and mesenteric veins (MV), pylephlebitis is caused by an uncontrolled infection in the portal system or intra-abdominal infection, leading to hematogenous dissemination of sepsis. Subsequently, thrombosis of the MV can lead to ischemia. Thrombus extension is associated to this condition in 42% of patients to the superior MV, and in 12% to the splenic vein[1].

Recent antibiotic therapy made pylephlebitis a rare condition. Rapid perfusion of broad-spectrum antibiotics and accurate diagnostic imaging were responsible for a decline in the mortality rate from 75% to 25%[1,3,4]. Nonspecific findings leading to delayed diagnosis are responsible for the high mortality rate of this condition[1,5-9].

As in our case, abdominal pain and fever are the most common presenting symptoms of pylephlebitis[10,11]. Except in cases where multiple liver abscesses are present, jaundice is a rare symptom[7]. Bacteremia is reached in the majority of patients and is the leading cause of death, followed by peritonitis, bowel ischemia, intestinal bleeding, or rupture of the PV[1,9].

In regards to etiology, pylephlebitis occurs most commonly in association with diverticulitis and appendicitis[9,12]; however, in a retrospective review performed by Choudhry et al[5] of 95 cases, pancreatitis was the main etiology[1,5]. In a small proportion of cases, inflammatory bowel disease was revealed to be the predisposing factor. In a study by Waxman et al[13], no primary source of infection could be identified up to 70% of patients. No age or gender predilection has been reported[1,6].

A CT scan showing thrombosis of the PV among with suppurative bacteriemia is the basis of the diagnosis, although US and MRI have also been used for the same purpose. There are no pathognomonic signs. The CT scan is helpful to determine clot resolution during follow-up[10,14]. In our patient, not only the diagnosis was obscured by the fact that the CT did not visualize the thrombophlebitis, but also the alternative diagnosis of metastatic pancreatic cancer seemed to be very convincing. Regarding the demonstration of a thrombus in the PV, contrast CT, US, MRI and MR angiography are usually considered to be very helpful.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of pylephlebitis following fish bone migration into the PV. In analyzing the sequence of events in this case, it would seem that the portal infection had already developed sometime prior to her admission to the hospital. However, the possibility of pylephlebitis was not even considered prior to EUS for further pancreatic biopsy. Considering that the patient had no history of weight loss, along with improvement in cholestatic pattern, other causes were sought, in addition to the hypothesis of neoplastic disease.

Regarding the pathological standpoint, the evidence was clear that the origin of the infection was fish bone ingestion, with perforation of the gastrointestinal tract and migration into the liver.

A high clinical suspicion for the diagnosis of patients presenting with unexplained fever and gastrointestinal symptoms is required, once that clinical manifestations are often confusing and nonspecific.

In 23%-88%, multiple organisms are isolated from blood cultures of patients[1,3,15]. The most common bloodstream isolate is usually normal bowel flora, such as Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli and Streptococcus sp.[8]. Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species, Aeromonas hydrophila, Clostridium species, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, yeasts, Citrobacter species and Enterococcus species have been described as well[3,15]. In contrast, in the retrospective series study performed by Choudhry et al[5], S. viridans was the most common microorganism cultured from blood samples.

After suspecting of pylephlebitis is suspected, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered immediately while waiting for cultures to be available. As no specific antibiotic therapy has been defined to this date, in cases where liver abscesses are present, current recommendations include 4 wk to 6 wk of antibiotic therapy with the inclusion of metronidazole, gentamicin, piperacillin, ceftizoxime, imipenem or ampicillin[6,8,14,16].

Quite often a hypercoagulable state, malignancy, or acquired immune deficiency syndrome are found in patients with this condition[2]. PV thrombosis may lead to fatal MV thrombosis. However, due to the limited data available, the role of anticoagulation therapy remains controversial. Anticoagulation minimizes sequelae and promotes recanalization, as well as reduce the incidence of septic embolization. Baril et al[11] suggested that patients with pylephlebitis and a hypercoagulable state, e.g., protein S deficiency, should be anticoagulated. According to a retrospective case series studies performed by Plemmons et al[8] and Kanellopoulou et al[1], the results suggested that patients who received both antibiotics and heparin had a better outcome than those who only received antibiotics. Three to six months of treatment is recommended by the studies, if no other underlying thrombotic disease is present[17]. In our case, we decided to treat with anticoagulation, and the patient was transitioned to complete a 6-mo course of enoxaparin on discharge.

Another severe complication is the development of hepatic abscess. With an incidence of 2.3 per 100000, pyogenic liver abscess is considered rare, which is higher in immunodeficient and diabetic patients. Due to the introduction and wide use of antibiotics and to the better understanding and operative techniques advancement, there has been a remarkable decline in the morbidity and mortality of pyogenic liver abscess. However, mortality ranges from 10%-12%[14].

Invasive procedures like thrombectomy and infection focus drainage may have a role in the treatment of pylephlebitis[8]. Single abscess smaller than 3 cm can be treated with antibiotics alone, but if larger than 3 cm, either percutaneous catheter drainage or needle aspiration should be provided[4]. Surgical thrombectomy grants higher rates of thrombosis recurrence[1,11], although it can be performed in patients who are non-responsive antibiotic and anticoagulation therapy[1].

In patients with suspicion of pylephlebitis, the diagnosis of thrombosis of the portal venous system has never been previously performed by using EUS. In suspected cases of thrombosis, the reliability of EUS in identifying the intra-abdominal vessels in normal volunteers or in assessing the patency of these vessels was investigated by Wiersema et al[18]. Duplex EUS was able to provide the correct diagnosis in 10 of 11 patients with nondiagnostic transabdominal US and suspected thrombosis of the portal system. The accuracy of EUS in 16 patients with PV system thrombosis (PVST) and in 29 patients without PVST as proven by surgery and/or CT scanning were determined by Lai and Brugge[19]. For the findings of PVST, the sensitivity and specificity of EUS were 81% and 93%, respectively[19]. In this setting, a good diagnostic quality of EUS is confirmed by the results. As demonstrated by our case, the correct diagnosis was performed by EUS, once it was apparent that the CT could not adequately show the intra-abdominal vessels. The close proximity of the mesenteric vasculature to the stomach and duodenum allows detailed imaging of these structures with EUS.

It is essential to recognize this uncommon yet dangerous complication. A prompt diagnosis of pylephlebitis leads to early treatment, which consists of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, along with consideration of anticoagulation., and more successful clinical outcomes. Although rare, it is important to keep in mind in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with unexplained fever and gastrointestinal symptoms.

This case report demonstrates for the first time the diagnosis of an unusual case of pylephlebitis complicated by the migration of a fish bone, mimicking metastatic pancreatic cancer. Clinical findings, traditional imaging studies, such as transabdominal US and CT, remain the standard for diagnosing this condition. However, for an alternative instrument in suspected cases with established methods, EUS offers an alternative.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Portugal

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yang F S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Kanellopoulou T, Alexopoulou A, Theodossiades G, Koskinas J, Archimandritis AJ. Pylephlebitis: an overview of non-cirrhotic cases and factors related to outcome. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42:804-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bolt RJ. Diseases of the hepatic blood vessels. In: Bockus HL. Gastroenterology. 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1985: 3259-3277. |

| 3. | Mailleux P, Maldague P, Coulier B. Pylephlebitis complicating peridiverticulitis without hepatic abscess: early detection with contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen. JBR-BTR. 2012;95:13-14. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Balthazar EJ, Gollapudi P. Septic thrombophlebitis of the mesenteric and portal veins: CT imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:755-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Choudhry AJ, Baghdadi YM, Amr MA, Alzghari MJ, Jenkins DH, Zielinski MD. Pylephlebitis: a Review of 95 Cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:656-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hoffman HL, Partington PF, Desanctis AL. Pylephlebitis and liver abscess. Am J Surg. 1954;88:411-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nobili C, Uggeri F, Romano F, Degrate L, Caprotti R, Perego P, Franciosi C. Pylephlebitis and mesenteric thrombophlebitis in sigmoid diverticulitis: medical approach, delayed surgery. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:1088-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Plemmons RM, Dooley DP, Longfield RN. Septic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein (pylephlebitis): diagnosis and management in the modern era. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1114-1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee BK, Ryu HH. A case of pylephlebitis secondary to cecal diverticulitis. J Emerg Med. 2012;42:e81-e85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saxena R, Adolph M, Ziegler JR, Murphy W, Rutecki GW. Pylephlebitis: a case report and review of outcome in the antibiotic era. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1251-1253. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Baril N, Wren S, Radin R, Ralls P, Stain S. The role of anticoagulation in pylephlebitis. Am J Surg. 1996;172:449-452; discussion 452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lerman B, Garlock JH, Janowitz HD. Suppurative pylephlebitis with multiple liver abscesses complicating regional ileitis: review of literature--1940-1960. Ann Surg. 1962;155:441-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Waxman BP, Cavanagh LL, Nayman J. Suppurative pyephlebitis and multiple hepatic abscesses with silent colonic diverticulitis. Med J Aust. 1979;2:376-378. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Kaewlai R, Nazinitsky KJ. Acute colonic diverticulitis in a community-based hospital: CT evaluation in 138 patients. Emerg Radiol. 2007;13:171-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wong K, Weisman DS, Patrice KA. Pylephlebitis: a rare complication of an intra-abdominal infection. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2013;3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nishimori H, Ezoe E, Ura H, Imaizumi H, Meguro M, Furuhata T, Katsuramaki T, Hata F, Yasoshima T, Hirata K, Asai Y. Septic thrombophlebitis of the portal and superior mesenteric veins as a complication of appendicitis: report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34:173-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Allaix ME, Krane MK, Zoccali M, Umanskiy K, Hurst R, Fichera A. Postoperative portomesenteric venous thrombosis: lessons learned from 1,069 consecutive laparoscopic colorectal resections. World J Surg. 2014;38:976-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wiersema MJ, Chak A, Kopecky KK, Wiersema LM. Duplex Doppler endosonography in the diagnosis of splenic vein, portal vein, and portosystemic shunt thrombosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:19-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lai L, Brugge WR. Endoscopic ultrasound is a sensitive and specific test to diagnose portal venous system thrombosis (PVST). Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:40-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |