Published online Aug 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6450

Peer-review started: March 21, 2021

First decision: April 29, 2021

Revised: May 11, 2021

Accepted: June 1, 2021

Article in press: June 1, 2021

Published online: August 6, 2021

Processing time: 125 Days and 22.8 Hours

Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors (PHNETs) are rare hepatic tumors. Their diagnosis, which is based on radiological findings, is difficult.

We present a case of PHNET in a 79-year-old man with no clinical symptoms. Computed tomography (CT) and 2-Deoxy-2-[fluorine-18] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT (18F-FDG PET/CT) were performed for further evaluation. A hypoattenuating mass with rim-like enhancement in segment 6 of the liver was detected on contrast-enhanced CT imaging. Increased uptake was also observed on 18F-FDG PET/CT. Histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations, which revealed a grade 2 neuroendocrine tumor (NET), confirmed the diagnosis.

Diagnosing PHNET is challenging, and must be distinguished from other liver tumors. Metastatic NETs should be excluded.

Core Tip: Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are rare hepatic tumors. The diagnosis of these tumors, based on radiological observations, is difficult, and requires distinguishing them from other liver tumors and excluding metastasized NETs. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography is helpful when excluding extrahepatic diseases and evaluating the prognosis. Pathological diagnosis based on histological and immunohistochemical evaluation is regarded as the standard diagnosis. Complete surgical resection is the only curative option. For inoperable cases, transarterial chemoembolization, chemotherapy, and radiofrequency ablation are alternative treatment methods.

- Citation: Rao YY, Zhang HJ, Wang XJ, Li MF. Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumor — 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography findings: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(22): 6450-6456

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i22/6450.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6450

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are relatively rare. Their incidence in the general population depends on the specific anatomic location. NETs can arise at almost any anatomical site of the body, and it most commonly develops in the gastrointestinal tract and bronchopulmonary system (73.7% and 25.1%, respectively)[1]. Metastases are the most common diagnostic considerations for hepatic NETs[2]. Primary hepatic NETs (PHNETs) are rare, with a low incidence of 0.3% among all NET cases[3]. Little is known about it because of its rarity. We present the case of a patient with PHNET who underwent 2-deoxy-2-[fluorine-18] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT).

A 79-year-old man presented to our hospital with an incidentally identified liver mass during a routine health checkup.

The patient had no clinical symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, fever, flushing, or abdominal pain.

The patient had a 10-year history of diabetes.

The patient had no remarkable family history.

The physical examination revealed no abnormal findings.

The blood serum levels of CEA (5.4 ng/mL; reference range 0-4.7), CA19-9 (52.4 U/mL; reference range 0-27), and CA12-5 (141 U/mL; reference range 0-35) were elevated. The alpha fetoprotein serum level was normal.

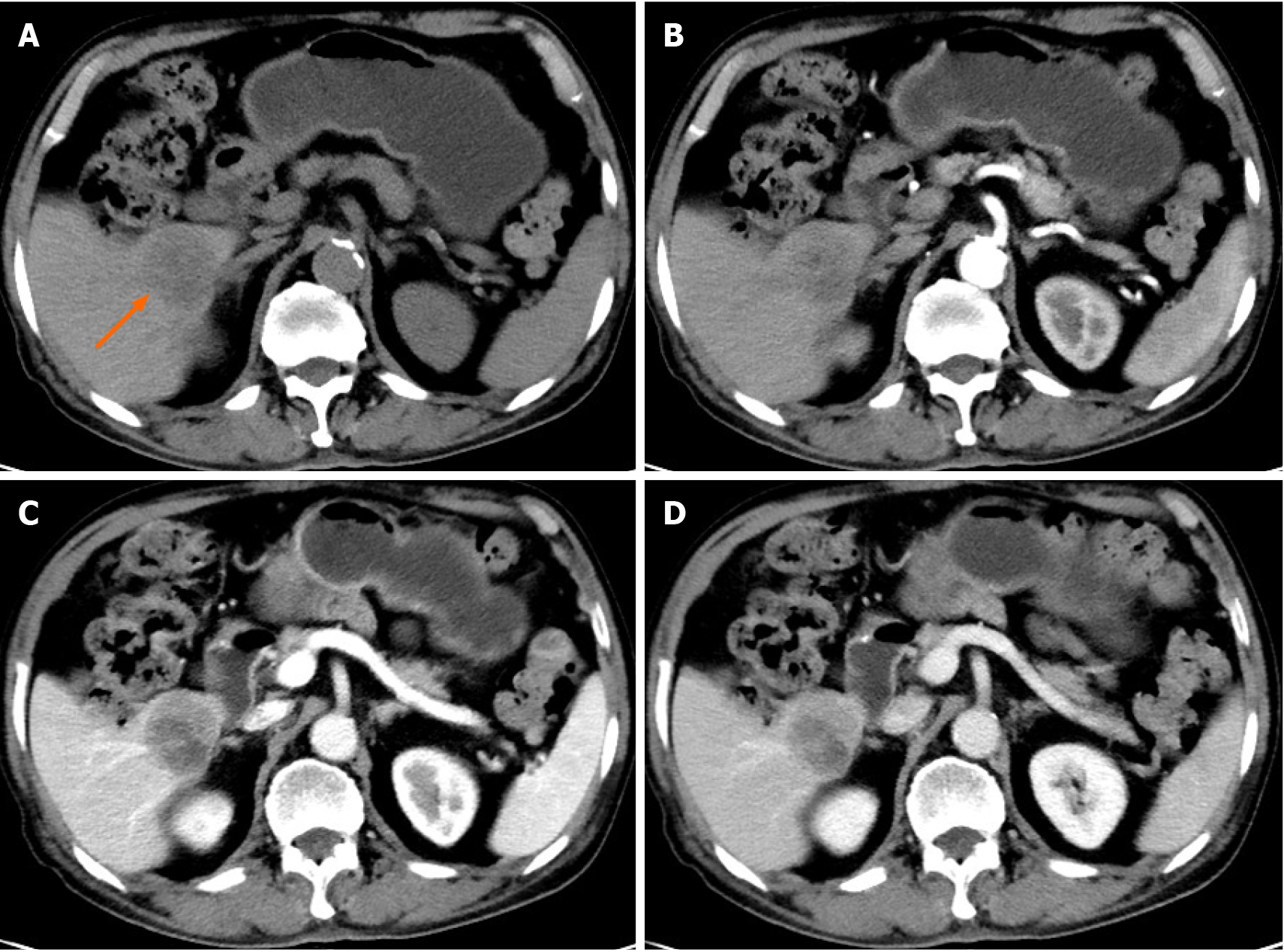

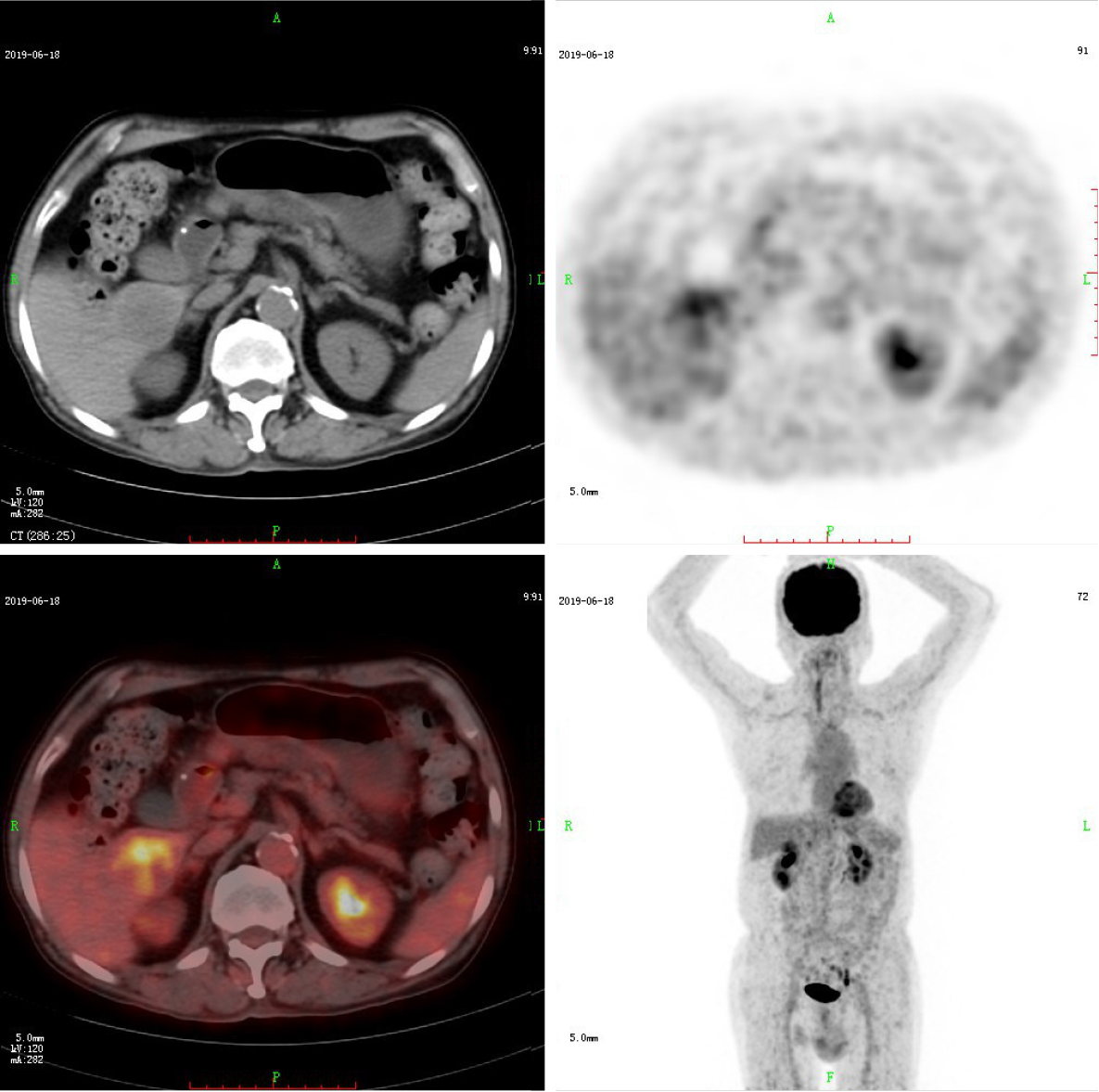

CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT demonstrated a solitary mass measuring 40 mm × 37 mm in the liver’s right lower lobe. Multidetector abdominal CT showed a well-circumscribed, heterogeneous, hypoattenuating mass. After contrast material was injected, the tumor was less enhanced than the adjacent normal liver with mild to moderate peripheral enhancement during the arterial, portal venous, and equilibrium phases (Figure 1). No cirrhosis was observed. 18F-FDG PET/CT images were obtained using a Gemini TF 64 PET/CT scanner (Philips, The Netherlands). 18F-FDG PET/CT showed increased uptake in the liver mass with a maximal standard uptake value (SUVmax) of 5.1. The SUVmax of the liver background was 2.0 (Figure 2). Except for the liver lesion, no extrahepatic abnormal activities were found on whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT.

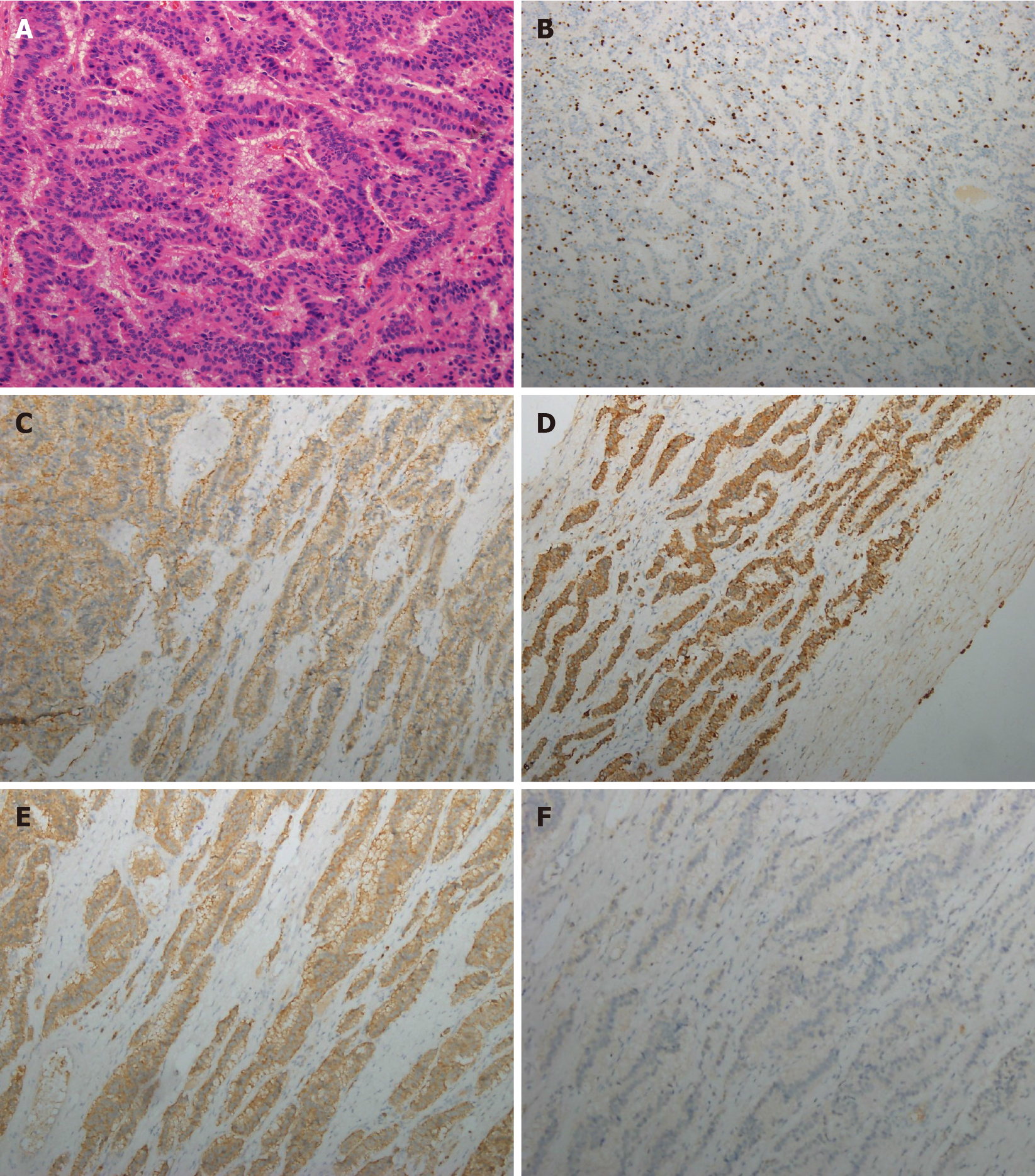

An ultrasound-guided liver biopsy was performed. Histological examination demon

Due to severe pulmonary dysfunction, the patient could not tolerate surgery. He underwent one course of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) with epirubicin (total dose of 50 mg) mixed with gelatin sponge particles and lipiodol. The patient’s blood serum levels of CEA (5.9 ng/mL; reference range 0-4.7), CA19-9 (109.2 U/mL reference range 0-27), and CA12-5 (166 U/mL reference range 0-35) were elevated. Abdominal magnetic resonance images showed no decrease in tumor size. Thus, the patient was treated by three courses of chemotherapy.

Partial response was achieved, and no extrahepatic lesions were radiologically found during the 18-mo follow-up. The patient was finally diagnosed with PHNET.

PHNET is a rare NET entity arising from Kulchitsky cells originating from the neural crest[2]. The total number of PHNET cases reported in the English literature is less than 200[5]. Due to its rarity, the clinical features and image findings are not well understood.

A classification system for neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) was established in 2000 and updated in 2019. Based on their molecular differences, NENs are divided into well-differentiated NETs and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas[1]. NETs are classified into three grades (G1, G2, and G3) according to their mitotic rate (mitoses/2 mm²) and Ki-67 proliferation index[4].

PHNETs are considered foregut carcinoid tumors, which typically grow slowly and have no function. They are commonly detected incidentally, occur in patients between 40-50 years of age, and are located in the liver’s right lobe[2,6].

Previous studies have shown that tumor markers such as alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and CA 19-9 have no diagnostic value for PHNET[5]. Imaging examinations, such as ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging, also have low sensitivity and specificity for PHNET. Both primary tumors and metastases appear at a low density on plain CT imaging. Hepatic metastases of NETs demonstrate rim enhancement in the arterial phase with washout in the portal venous and equili

The pathological diagnosis, which is based on histological and immunohistochemical evaluations, is the standard diagnosis. Liver metastases of NETs are more common than PHNETs, and no significant radiological difference is found between them. Thus, diagnosing PHNET is challenging, and metastatic NETs should have been excluded[8].

In this study, immunohistochemical examinations revealed positive immunoreactivities for CD56, CK AE1/AE3, Syn, which confirmed the tumor was a NEN. Negative expressions of CDX-2 and TTF-1 helped rule out the possibility of small bowel, appendix, lung, and thyroid origins. Thus, we confirmed the diagnosis by histology and imaging methods, such as 18F-FDG PET/CT.

A previous study investigated the utility of 18F-FDG PET in patients with NET grades 1 and 2. The results of 18F-FDG PET examinations were positive in 57% of patients with NET G1, and 66% of patients with NET G2[9]. Sansovini et al[10] demonstrated that patients with negative FDG PET results had better outcomes than those with positive scans. FDG PET was an independent prognostic factor in advanced pancreatic NETs. Binderup et al[11] showed that compared to traditional markers, such as the Ki-67 index, 18F-FDG PET had a higher prognostic value. Despite its low diagnostic sensitivity, 18F-FDG PET/CT has a high prognostic value for NETs. Whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT is helpful for excluding extrahepatic diseases[12].

Complete surgical resection is the only curative option, and it results in a 5year survival rate of 74%-78%. Up to 85% of tumors are resectable[3,13]. Alternative treatment methods for inoperable cases include TACE, chemotherapy, and radiofrequency ablation. Yao et al[14] reported that hepatic chemoembolization for NETs effectively improved clinical symptoms and achieved tumor control. In our case, the patient had severe pulmonary dysfunction, and surgery was not considered. There

In conclusion, PHNET is a rare liver tumor that presents with nonspecific clinical symptoms. Its diagnosis should be made based on immunohistochemistry findings, and metastatic NETs need to be excluded. 18F-FDG PET/CT can help exclude extra

| 1. | Rindi G, Klimstra DS, Abedi-Ardekani B, Asa SL, Bosman FT, Brambilla E, Busam KJ, de Krijger RR, Dietel M, El-Naggar AK, Fernandez-Cuesta L, Klöppel G, McCluggage WG, Moch H, Ohgaki H, Rakha EA, Reed NS, Rous BA, Sasano H, Scarpa A, Scoazec JY, Travis WD, Tallini G, Trouillas J, van Krieken JH, Cree IA. A common classification framework for neuroendocrine neoplasms: an International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and World Health Organization (WHO) expert consensus proposal. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:1770-1786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 546] [Cited by in RCA: 774] [Article Influence: 96.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Baxi AJ, Chintapalli K, Katkar A, Restrepo CS, Betancourt SL, Sunnapwar A. Multimodality Imaging Findings in Carcinoid Tumors: A Head-to-Toe Spectrum. Radiographics. 2017;37:516-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shah D, Mandot A, Cerejo C, Amarapurkar D, Pal A. The Outcome of Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Single-Center Experience. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2019;9:710-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 2748] [Article Influence: 458.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Li YF, Zhang QQ, Wang WL. Clinicopathological Characteristics and Survival Outcomes of Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumor: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Population-Based Study. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e923375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Baek SH, Yoon JH, Kim KW. Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumor: gadoxetic acid (Gd-EOB-DTPA)-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Radiol Short Rep. 2013;2:2047981613482897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang LX, Liu K, Lin GW, Jiang T. Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors: comparing CT and MRI features with pathology. Cancer Imaging. 2015;15:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ichiki M, Nishida N, Furukawa A, Kanasaki S, Ohta S, Miki Y. Imaging findings of primary hepatic carcinoid tumor with an emphasis on MR imaging: case study. Springerplus. 2014;3:607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Severi S, Nanni O, Bodei L, Sansovini M, Ianniello A, Nicoletti S, Scarpi E, Matteucci F, Gilardi L, Paganelli G. Role of 18FDG PET/CT in patients treated with 177Lu-DOTATATE for advanced differentiated neuroendocrine tumours. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:881-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sansovini M, Severi S, Ianniello A, Nicolini S, Fantini L, Mezzenga E, Ferroni F, Scarpi E, Monti M, Bongiovanni A, Cingarlini S, Grana CM, Bodei L, Paganelli G. Long-term follow-up and role of FDG PET in advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine patients treated with 177Lu-D OTATATE. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:490-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Binderup T, Knigge U, Loft A, Federspiel B, Kjaer A. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts survival of patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:978-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mitamura K, Yamamoto Y, Tanaka K, Sanomura T, Murota M, Nishiyama Y. (18)F-FDG PET/CT Imaging of Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumor. Asia Ocean J Nucl Med Biol. 2015;3:58-60. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Morishita A, Yoneyama H, Nomura T, Sakamoto T, Fujita K, Tani J, Miyoshi H, Haba R, Masaki T. Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumor: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;4:954-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yao KA, Talamonti MS, Nemcek A, Angelos P, Chrisman H, Skarda J, Benson AB, Rao S, Joehl RJ. Indications and results of liver resection and hepatic chemoembolization for metastatic gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery. 2001;130:677-682; discussion 682-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Garcia-Carbonero R, Rinke A, Valle JW, Fazio N, Caplin M, Gorbounova V, O Connor J, Eriksson B, Sorbye H, Kulke M, Chen J, Falkerby J, Costa F, de Herder W, Lombard-Bohas C, Pavel M; Antibes Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Systemic Therapy 2: Chemotherapy. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;105:281-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zhang X S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yuan YY