Published online Jun 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4829

Peer-review started: February 8, 2021

First decision: April 25, 2021

Revised: May 4, 2021

Accepted: May 8, 2021

Article in press: May 8, 2021

Published online: June 26, 2021

Processing time: 122 Days and 21.9 Hours

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare and aggressive cutaneous neuroendocrine neoplasia, with high risk of recurrence and metastasis and poor survival. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, like the anti-programmed death-ligand 1 agent avelumab, were recently approved for the treatment of advanced MCC. We, herein, report the first case of advanced MCC with oligoprogression managed with avelumab and local radical treatment.

A 61-year-old man was presented to the hospital with sporadic fever and an exudative malodorous mass (10 cm of diameter), located on the right gluteal region. The final diagnosis was MCC, cT4N3M1c (AJCC, TNM staging 8th edition, 2017), with invasion of adjacent muscle, in-transit metastasis, and bone lesions. Patient started chemotherapy (cisplatin and etoposide), and after six cycles, the main tumor increased, evidencing disease progression. Two months later, the patient started second line treatment with avelumab (under an early access program). After two cycles of treatment, the lesion started to decrease, achieving a major response. Local progression was documented after 16 cycles. However, as the tumor became resectable, salvage surgery was performed, while keeping the systemic treatment with avelumab. Since the patient developed bilateral pneumonia, immunotherapy was suspended. More than 2.5 years after surgery (last 19 mo without systemic therapy), the patient maintains complete local response and stable bone lesions.

This report highlights the efficacy and long-term response of avelumab on the management of a chemotherapy resistant advanced MCC, with evidence of oligoprogression, in combination with local radical treatment.

Core Tip: This report highlights the efficacy and long-term response of avelumab on the management of a chemotherapy resistant advanced Merkel cell carcinoma. It shows also a successful approach to oligoprogression with local radical treatment, surgery, and radiotherapy, while maintaining systemic therapy with avelumab. The results support the effectiveness of this strategy for the management of unresectable Merkel cell carcinoma.

- Citation: Leão I, Marinho J, Costa T. Long-term response to avelumab and management of oligoprogression in Merkel cell carcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(18): 4829-4836

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i18/4829.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4829

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare and aggressive cutaneous neuroendocrine neoplasia, with early metastization and low survival rates[1]. The majority of patients can be included in one of the following risk groups: Elderly, immunocompromised patients, patients with history of high ultraviolet radiation exposure, and patients with hematological malignancies or other skin tumors[1-3]. MCC can also be associated with the presence of Merkel cell polyomavirus, an ubiquitous virus present in the skin of the majority of healthy people, which can be detected in about 80% of MCC tumors[3-5].

Treatment of MCC depends on both tumor characteristics and patient performance status[6]. For the management of localized resectable tumors, international guidelines recommend wide local excision. This strategy is often a challenge since most of these tumors occur across the head and neck region. Until 2016, chemotherapy was the standard of care for unresectable MCCs, with immediate response, but with early recurrence and low survival rates[7-10]. The emergence of immune checkpoint inhibitors revolutionized the therapeutic strategies adopted for several tumor types. MCC is not an exception[11], due to the frequent expression of programmed death-ligand 1 on MCC tumor cells and of programmed death 1 on Merkel cell polyo

We can only find a few reports on the use of avelumab in MCC treatment[13-15]. We, herein, report the first case of advanced MCC, with oligoprogression, managed with avelumab and local radical treatment, presenting long-term disease control after immunotherapy suspension.

A 61-year-old man was presented to the hospital with sporadic fever and an exudative mass, located on the right gluteal region.

One year before the medical oncology consultation, the patient noticed a small nodule located on the right gluteal region, which kept growing and became exudative and bloody. For several weeks the patient refused to leave his house, as he was uncomfortable due to physical constraints. When he decided to attend the emergency department, the lesion was about 9 cm in diameter and was bloody and exudative. The patient also reported episodic fever, predominantly in the morning, in the week before the consultation. A biopsy was performed on that same day, and the patient was reassessed a few weeks later on a medical oncology consultation.

The patient had a history of arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

The patient had a history of arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and COPD.

On the first medical oncology consultation, the patient presented a 10 cm (diameter) malodorous painless mass, located on the right gluteal region, with hard consistency and bloody seropurulent discharge. Upon physical examination, two painless inguinal lymph nodes were also found, both fixed, with hard consistency and diameter of 2 cm on the left side and 3.5 cm on the right side.

Anatomopathological analysis: The anatomopathological examination of the right gluteal mass confirmed the diagnosis of MCC positive for cytokeratin AE1AE3 and chromogranin.

Imaging studies were obtained. An abdomen and pelvic computed tomography highlighted a large mass in the right gluteal region measuring 9.6 cm × 3.2 cm × 9.0 cm (in transverse, anteroposterior and longitudinal diameters, respectively), and a similar nodular soft tissue lesion with 2.4 cm × 1.5 cm × 2.4 cm in the vicinity of the mass. Large inguinal heterogeneous lymph nodes were also identified, with the largest one located on the right side (2.6 cm × 1.8 cm × 5.0 cm).

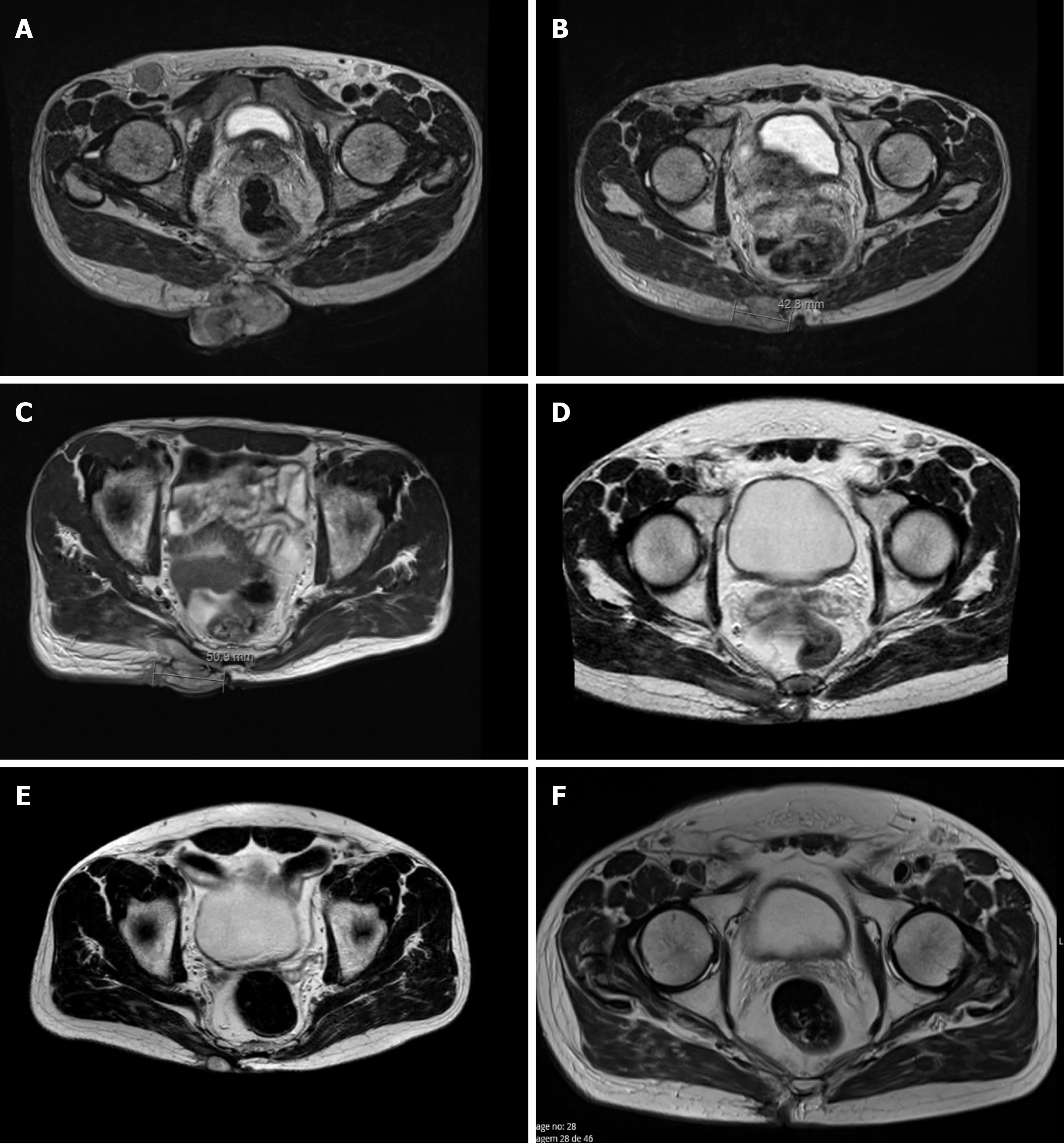

Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the existence of an expansive, heterogeneous lesion with lobulated contour and exophytic component located in the right gluteal region, involving the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and extending to the right gluteus maximus muscle in its inner portion (7.5 cm × 4.8 cm × 7.7 cm; Figure 1A). The images confirmed other subcutaneous lesion, with similar characteristics, measuring 2.4 cm × 1.2 cm, and three other small nodules, permeating the muscles between the gluteus maximus and maxillary muscles near the right hip. Bilateral inguinal lymph nodes, with 3.8 cm × 1.9 cm and 3.3 cm × 2.0 cm, were also evident and highly suspicious. The exam also revealed two bone lesions, one in the sacrum (2.8 cm) and another in the left iliac wing (2.4 cm), both compatible with bone metastasis. However, these lesions were not visible in the bone scintigraphy that was also performed, which in turn revealed two other bone lesions on the body of D11 and in the ninth right costal arch, with uncertain etiology and suspected of metastasis, in the additional MRI.

The case was discussed in the Multidisciplinary Tumor Board, with the presence of Medical Oncology, Radio-Oncology, Dermatology, and Plastic Surgery specialists. Considering the diagnosis of unresectable tumor, the Multidisciplinary Tumor Board decided for palliative chemotherapy.

The final diagnosis was MCC of the right gluteal region, cT4N3M1c (AJCC, TNM staging 8th edition, 2017), with invasion of adjacent muscle, in-transit metastasis (with regional lymph nodes), and bone metastasis.

Patient started chemotherapy, with cisplatin 75 mg/m2 D1 and etoposide 100 mg/m2

The patient started avelumab with good tolerance and no adverse events. Clinical response was reported after two cycles as the gluteal lesion started to decrease in size (6 cm × 7 cm), presenting signs of necrosis (Figure 2B), but with improvement in patient’s quality of life. By cycle 5, the lesion was significantly reduced, closed completely, and became flat and dry. Maximum clinical response was achieved after seven treatments (Figure 2C). Lymph nodes became infracentimetric, and the patient recovered appetite and reported feeling generally well. This clinical response was confirmed by MRI, which showed a reduction of the lesion located in the gluteal region (5.7 cm × 6.0 cm × 1.9 cm; Figure 1D) and evidenced a shrinkage of the infiltrative lesions involving the right wing of the sacrum (maximum diameter: 2.6 cm) and the iliac bone (maximum diameter: 2.1 cm). An MRI performed at cycle 14 confirmed further reduction of the tumoral wound (3.8 cm × 3.5 cm × 1.2 cm; Figure 1E).

However, after 16 cycles of treatment, the tumoral wound showed an increase (about 3 cm), compatible with primary tumor progression (Figure 2D). Bone and lymph node metastases were stable. Nevertheless, as the primary tumor was considered resectable at this point, the patient was proposed for surgery followed by radiotherapy.

The lesion was excised with tumor free margins (R0) and, 3 wk after surgery, the patient started radiotherapy, with a total dose of 56 Gy in 28 fractions, 2 Gy/fr, five times a week. At this time, he also resumed the systemic treatment with avelumab, at the same dose and schedule. Three months later (cycle 28), a pelvic MRI showed no evidenced of local disease (Figures 1F and 2E).

After 41 cycles of avelumab, treatment was interrupted due to a bilateral pneumococcal pneumonia, with bacteremia and respiratory failure (lung infection grade 4, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v.5.0). As the patient had a history of pulmonary chronic disease, it was not possible to assume a treatment-related adverse event. However, after discussing with the patient possible alternatives and outcomes, the medical team decided to suspend immunotherapy and maintain follow-up.

More than 40 mo after starting avelumab, the patient is alive and well. Since surgery, with more than 2.5 years of follow-up, the patient maintains complete local response (Figure 2F) and stable bone lesions, even after stopping systemic immunotherapy more than 1.5 years ago.

MCC is a rare cutaneous aggressive disease, with high risk for metastasis and increased case-fatality rate when compared to other skin cancers[1,16]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors were recently approved for the treatment of advanced MCC[17]. Avelumab is an anti-programmed death-ligand 1 monoclonal antibody, approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (2017) and the European Medicine Agency (2018) as the first line treatment for metastatic MCC, based on the results of a phase II clinical trial[18-20]. The trial included patients unresponsive to chemotherapy and reported an objective response rate of 33.0% as well as a median overall survival of 12.9 mo (95%CI: 7.5-not estimable), with a good safety profile. Since then, several studies and trials highlighted immunotherapy as a turning point in MCC patients care[21].

To the best of our knowledge, the presented case is the first report describing the evolution of an unresectable MCC with bone metastasis and its management after oligoprogression. Our patient was presented to the first oncology appointment highly debilitated and symptomatic, with an advanced stage disease, a massive irresectable primary tumor, and bone metastization. Despite undetected by bone scintigraphy, two bone lesions in the sacrum and left iliac wing were highly suspicious in MRI imaging. Since MCC bone metastasis can be osteolytic or osteoblastic, bone scintigraphy may not be the best exam to diagnose or exclude bone metastasis. Nevertheless, two other bone lesions on D11 and in the ninth right costal arch were seen in both exams.

Considering the diagnosis, we decided for a palliative care based on chemotherapy with etoposide and cisplatin. The treatment provided a good initial response but without long lasting effects, as previously described by other authors[7]. For second line treatment, the patient integrated an early access program, with avelumab. Immunotherapy had a dramatic effect on primary tumor, with downsizing of the lesion and promotion of the cicatricial process, with positive impact on patient’s symptoms and improved autonomy, allowing the patient to return to work. With these effects, the lesion became resectable and surgery became possible upon a local progression scenario. The use of avelumab, as an induction treatment strategy, followed by surgery and radiotherapy, showed to be an effective strategy to manage oligoprogressive disease.

The concept of oligoprogressive disease has been mainly discussed in lung cancer. The proposed treatment approach is based on keeping the strategy that proved to control the greater proportion of the disease, while using other strategies to treat the area of disease in progression[22,23]. In fact, this concept totally resembles our case: After 14 cycles of treatment, even though the disease was overall controlled (bone metastasis were stable and no de-novo lesions were detected), there were signs of primary tumor progression (oligoprogression). The adopted approach allowed to maintain the control of the metastatic disease, while providing conditions to manage the primary lesion with radical local therapy.

The rapid and durable response observed in this clinical case (a chemotherapy-refractory patient), along with the idea suggested by Kaufman et al[18] that the immune system may be more functional in patients who received fewer lines of therapy[18], advocates that a brief period of neoadjuvant therapy might suffice to mediate substantial tumor regression, potentially enabling surgery in patients with localized unresectable MCC, as reported in a recent clinical case report[13]. Similarly, in the CheckMate 358 Trial, Topalian et al[24] evaluated the safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant nivolumab in resectable MCC and reported that, among the 36 patients who underwent surgery, the polymerase chain reaction rate was 47.2%. However, 3 patients did not undergo surgery because of disease progression or adverse events[24].

It is estimated that about 1% of the patients treated with avelumab develop immune-related pneumonitis[18], usually in the first few months of treatment, and that COPD is a risk factor for drug-induced pulmonary toxicity[25]. Therefore, even though it is not reasonable to establish a direct causal association between immunotherapy and pulmonary disease, avelumab may have played a role in the predisposition of this patient with COPD to develop severe bacterial pneumonia. In this context, before starting immunotherapy, it might be advisable to characterize fully these types of comorbidities and perform a specialized evaluation by a pneumologist in order to optimize patients’ comorbidities, in advance.

In case of progression, it is of major importance to have a risk/benefits discussion with the patient. Due to the rarity of this disease and to the lack of solid evidence, inclusion in a clinical trial is advisable. If not available, the multidisciplinary group shall consider the possibility to resume immunotherapy with caution (because of the pulmonary adverse event reported), as avelumab was suspended more than 12 mo and the response rate and duration of response to chemotherapy are very limited[9]. Local radical treatment options may also be considered in case of oligoprogression. Furthermore, recent case reports showed optimistic results on the use of nivolumab and ipilimumab in MCC refractory to avelumab[26,27]. However, a substantial increased risk for immune-related adverse events is a major concern.

To the authors’ knowledge, the use of avelumab beyond progression in MCC or as part of oligoprogression management strategies has not been reported previously. Considering the heterogeneity of these tumors, with different location and distinct degrees of disease progression, the real potential of avelumab is yet to be known. In this context, clinicians and researchers shall share the outcomes of their clinical practice, mainly in a rare disease like MCC. This report highlights the long-term efficacy of avelumab on the management of a chemotherapy resistant advanced MCC. It also shows a successful approach to oligoprogression with local radical treatment, surgery, and radiotherapy, while maintaining systemic therapy with avelumab.

The authors thank Paula Pinto, PharmD, PhD (PMA–Pharmaceutical Medicine Academy) for providing medical writing and editorial assistance.

| 1. | Becker JC, Stang A, DeCaprio JA, Cerroni L, Lebbé C, Veness M, Nghiem P. Merkel cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P. Update on Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12:31-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kervarrec T, Samimi M, Guyétant S, Sarma B, Chéret J, Blanchard E, Berthon P, Schrama D, Houben R, Touzé A. Histogenesis of Merkel Cell Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Review. Front Oncol. 2019;9:451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2611] [Cited by in RCA: 2338] [Article Influence: 129.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | DeCaprio JA. Merkel cell polyomavirus and Merkel cell carcinoma. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2017;372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cassler NM, Merrill D, Bichakjian CK, Brownell I. Merkel Cell Carcinoma Therapeutic Update. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016;17:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Steven N, Lawton P, Poulsen M. Merkel Cell Carcinoma - Current Controversies and Future Directions. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2019;31:789-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tai PT, Yu E, Winquist E, Hammond A, Stitt L, Tonita J, Gilchrist J. Chemotherapy in neuroendocrine/Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: case series and review of 204 cases. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2493-2499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nghiem P, Kaufman HL, Bharmal M, Mahnke L, Phatak H, Becker JC. Systematic literature review of efficacy, safety and tolerability outcomes of chemotherapy regimens in patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2017;13:1263-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Villani A, Fabbrocini G, Costa C, Carmela Annunziata M, Scalvenzi M. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Therapeutic Update and Emerging Therapies. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9:209-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Seebacher NA, Stacy AE, Porter GM, Merlot AM. Clinical development of targeted and immune based anti-cancer therapies. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Specenier P, Vermorken JB. Optimizing treatments for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:901-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Abdallah N, Nagasaka M, Chowdhury T, Raval K, Hotaling J, Sukari A. Complete response with neoadjuvant avelumab in Merkel cell carcinoma - A case report. Oral Oncol. 2019;99:104350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ramachandran P, Erdinc B, Gotlieb V. An Unusual Presentation of Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a HIV Patient: A Case Report and Literature Review. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2019;7:2324709619836695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Cardis MA, Jiang H, Strauss J, Gulley JL, Brownell I. Diffuse lichen planus-like keratoses and clinical pseudo-progression associated with avelumab treatment for Merkel cell carcinoma, a case report. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Emge DA, Cardones AR. Updates on Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:489-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gaiser MR, Bongiorno M, Brownell I. PD-L1 inhibition with avelumab for metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018;11:345-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kaufman HL, Russell J, Hamid O, Bhatia S, Terheyden P, D'Angelo SP, Shih KC, Lebbé C, Linette GP, Milella M, Brownell I, Lewis KD, Lorch JH, Chin K, Mahnke L, von Heydebreck A, Cuillerot JM, Nghiem P. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a multicentre, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1374-1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 830] [Cited by in RCA: 969] [Article Influence: 96.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kaufman HL, Russell JS, Hamid O, Bhatia S, Terheyden P, D'Angelo SP, Shih KC, Lebbé C, Milella M, Brownell I, Lewis KD, Lorch JH, von Heydebreck A, Hennessy M, Nghiem P. Updated efficacy of avelumab in patients with previously treated metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma after ≥1 year of follow-up: JAVELIN Merkel 200, a phase 2 clinical trial. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | De Sousa Linhares A, Battin C, Jutz S, Leitner J, Hafner C, Tobias J, Wiedermann U, Kundi M, Zlabinger GJ, Grabmeier-Pfistershammer K, Steinberger P. Therapeutic PD-L1 antibodies are more effective than PD-1 antibodies in blocking PD-1/PD-L1 signaling. Sci Rep. 2019;9:11472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chan IS, Bhatia S, Kaufman HL, Lipson EJ. Immunotherapy for Merkel cell carcinoma: a turning point in patient care. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Laurie SA, Banerji S, Blais N, Brule S, Cheema PK, Cheung P, Daaboul N, Hao D, Hirsh V, Juergens R, Laskin J, Leighl N, MacRae R, Nicholas G, Roberge D, Rothenstein J, Stewart DJ, Tsao MS. Canadian consensus: oligoprogressive, pseudoprogressive, and oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Oncol. 2019;26:e81-e93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Rowe SP, Tran PT, Fishman EK, Johnson PT. Oligoprogression: What Radiologists Need to Know About This Emerging Concept in Cancer Therapeutic Decision-making. Acad Radiol. 2017;24:898-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Topalian SL, Bhatia S, Amin A, Kudchadkar RR, Sharfman WH, Lebbé C, Delord JP, Dunn LA, Shinohara MM, Kulikauskas R, Chung CH, Martens UM, Ferris RL, Stein JE, Engle EL, Devriese LA, Lao CD, Gu J, Li B, Chen T, Barrows A, Horvath A, Taube JM, Nghiem P. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab for Patients With Resectable Merkel Cell Carcinoma in the CheckMate 358 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2476-2487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chuzi S, Tavora F, Cruz M, Costa R, Chae YK, Carneiro BA, Giles FJ. Clinical features, diagnostic challenges, and management strategies in checkpoint inhibitor-related pneumonitis. Cancer Manag Res. 2017;9:207-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Glutsch V, Kneitz H, Goebeler M, Gesierich A, Schilling B. Breaking avelumab resistance with combined ipilimumab and nivolumab in metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma? Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1667-1668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Khaddour K, Rosman IS, Dehdashti F, Ansstas G. Durable remission after rechallenge with ipilimumab and nivolumab in metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma refractory to avelumab: Any role for sequential immunotherapy? J Dermatol. 2021;48:e80-e81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Portugal

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lee HJ S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX