Published online Oct 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i20.4993

Peer-review started: July 15, 2020

First decision: August 8, 2020

Revised: August 10, 2020

Accepted: September 16, 2020

Article in press: September 16, 2020

Published online: October 26, 2020

Processing time: 103 Days and 0.4 Hours

Spontaneous bladder rupture is relatively rare, and common causes of spontaneous bladder rupture include bladder diverticulum, neurogenic bladder dysfunction, gonorrhea infection, pelvic radiotherapy, etc. Urinary bladder perforation caused by urinary catheterization mostly occurs during the intubation process.

Here, we describe an 83-year-old male who was admitted with 26 h of middle and upper abdominal pain and a history of long-term catheterization. Physical examination and computed tomography of the abdomen supported the diagnosis of diffuse peritonitis, most likely from a perforated digestive tract organ. Laparoscopic exploration revealed a possible digestive tract perforation. Finally, a perforation of approximately 5 mm in diameter was found in the bladder wall during laparotomy. After reviewing the patient’s previous medical records, we found that 1 year prior the patient underwent an ultrasound examination showing that the end of the catheter was embedded into the mucosal layer of the bladder. Therefore, the bladder perforation in this patient may have been caused by the chronic compression of the urinary catheter against the bladder wall.

For patients with long-term indwelling catheters, there is a possibility of bladder perforation, which needs to be dealt with quickly.

Core Tip: Here, we describe a patient, who had a long-term indwelling catheter and complained of abdominal pain, with a bladder perforation that was mistaken for a gastrointestinal perforation. We found that 1 year prior the patient underwent an ultrasound examination showing that the end of the catheter was embedded in the mucosal layer of the bladder. Therefore, the bladder perforation in this patient may have been caused by the chronic compression of the urinary catheter against the bladder wall. This case reminds us that for patients with long-term indwelling catheters, bladder perforation may occur and needs to be dealt with timely.

- Citation: Wu B, Wang J, Chen XJ, Zhou ZC, Zhu MY, Shen YY, Zhong ZX. Bladder perforation caused by long-term catheterization misdiagnosed as digestive tract perforation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(20): 4993-4998

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i20/4993.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i20.4993

Bladder perforation is commonly seen in trauma or iatrogenic injury[1], such as transurethral surgery or pelvic intraoperative injury[2,3]. Spontaneous bladder rupture is relatively rare, and common causes of spontaneous bladder rupture include bladder diverticulum, neurogenic bladder dysfunction, gonorrhea infection and pelvic radiotherapy, among others[4]. A urinary bladder perforation caused by urinary catheterization mostly occurs during the intubation process. Here, we describe a patient who had a bladder perforation combined with peritonitis due to the long-term indwelling of the catheter.

An 83-year-old male patient came to our hospital for emergency treatment due to 26 h of middle and upper abdominal pain.

The patient had mid-upper abdominal pain 26 h ago, a persistent pain, severe with nausea but no vomiting. There was no waist and back pain, no chest tightness, shortness of breath, but the patient felt palpitations and fatigue. The patient has had chills since abdominal pain occurred, and the degree of abdominal pain has been increasing since the onset. We observed that the patient had a catheter inserted, and there was about 50 mL of yellow urine in the urine bag.

After a careful medical history inquiry, the patient was found to have been bedridden for a long period of time and suffered from many diseases, including hypertension, cardiac pacemaker implantation, history of atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, prostatic hyperplasia and catheter indwelling status. The patient was diagnosed with benign prostatic hyperplasia 8 years ago due to symptoms of impaired urination, but he refused surgery. Three years ago, the patient could not rule out urination because of prostate hyperplasia, so he chose catheterization. For so many years, patients have been living with urinary catheters, so urinary tract infections often occur.

When the patient came to the hospital, his temperature was 37.2°C, heart rate was 56 bpm, respiratory rate was 19 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 197/70 mmHg and oxygen saturation was 97%. Physical examination revealed slightly swollen abdomen and no obvious prominent lumps. Abdominal palpation showed tense abdominal muscles, a platy abdomen and obvious tenderness in the whole abdomen accompanied by rebound pain. Percussion of the abdomen indicated the presence of fluid in the abdominal cavity. Auscultation of the abdomen indicated that the sound of bowel movement in the abdominal cavity was slightly weakened.

Routine blood tests showed that the patient’s leukocyte count did not increase significantly (7.38 × 109/L), and the percentage of neutrophils was 91.2% with an increased hypersensitive C-reactive protein (132.81 mg/L). The patient’s red blood cell count was normal (4.92 × 109/L), but the platelet count was low (80 × 109/L). The significant increase in troponin (50 ng/L) and brain natriuretic peptide (630.53 pg/mL) indicated that the function of the patient’s heart was poor. Prothrombin, d-dimers and partial thromboplastin times were normal.

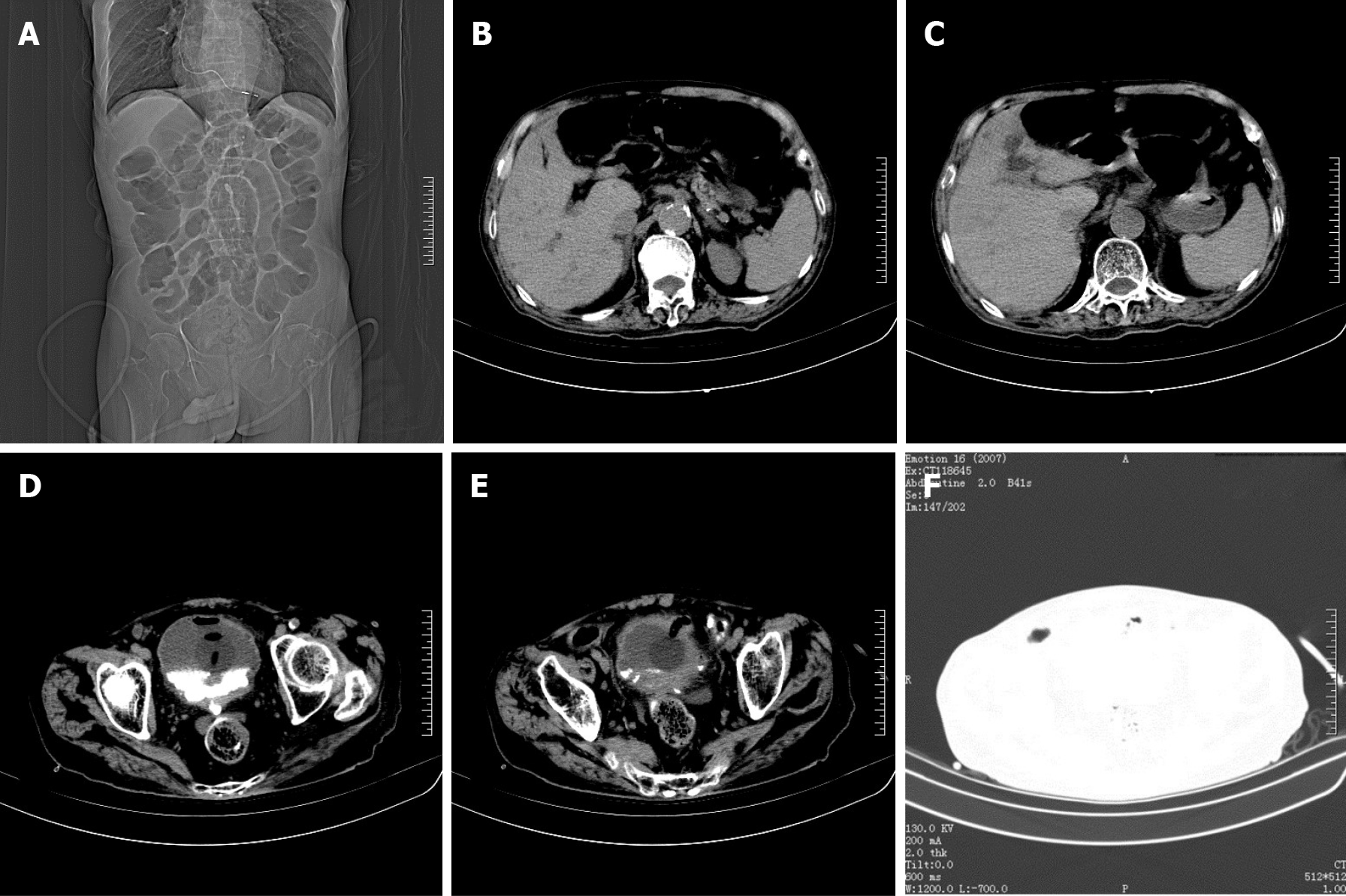

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed a small amount of free gas under the diaphragm and edema in part of the small intestine and intestinal wall with surrounding exudation. There was gas accumulation in the middle and upper abdomen and intestinal cavity, a small amount of effusion around the right liver, multiple cystic foci in the liver and cirrhosis. The distal end of the common bile duct showed calculi with multiple gallbladder calculi. The bladder wall was thickened with multiple bladder diverticulum and gas accumulation (Figure 1).

The on duty physician first considered a diagnosis of diffuse peritonitis most likely due to a perforation of the digestive tract based on the above physical examination features and imaging data.

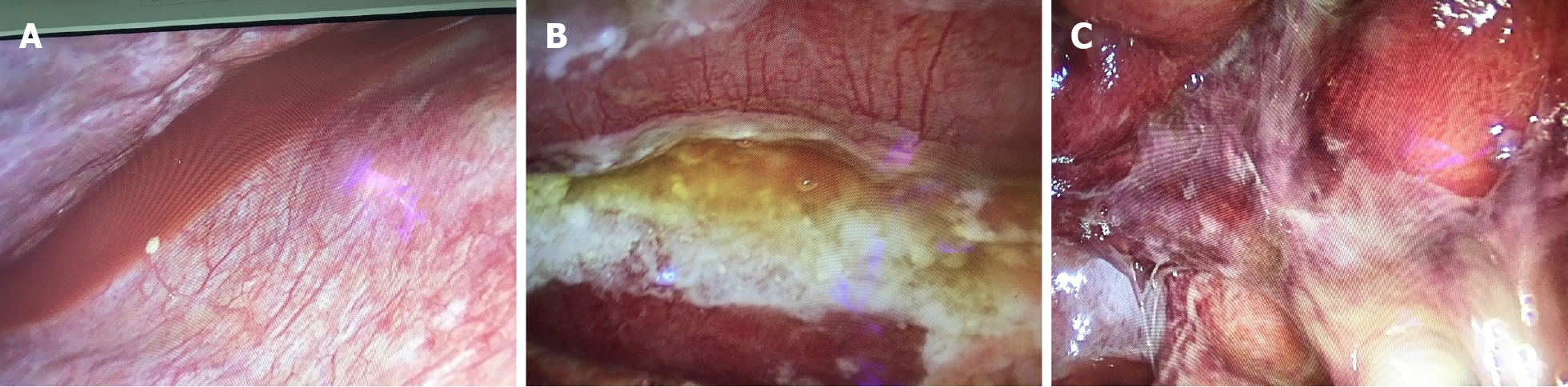

Due to the advanced age of the patient with many basic diseases, the patient was at high risk for surgical treatment. After consultation with the patient’s family, the patient underwent emergency laparoscopic exploration. During the operation, dark red fluid accumulation was observed around the liver (Figure 2A) and a large amount of purulent fluid and pus adhesions were observed in the abdominal cavity (Figure 2B and C) when the laparoscope was inserted into the abdominal cavity, indicating that a digestive tract perforation was more likely. We performed exploratory laparotomy in the hope of finding the location of the perforation.

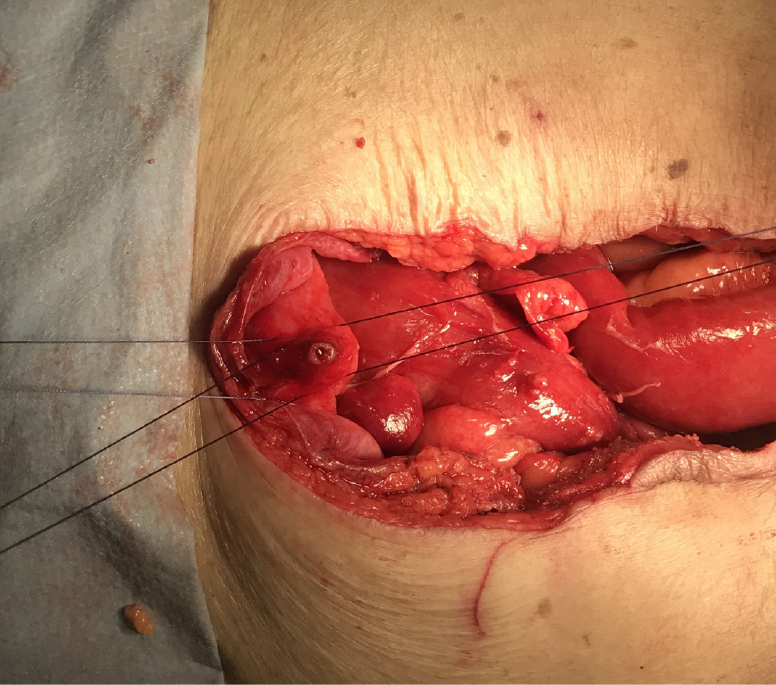

Finally, a hole of approximately 5 mm in diameter was found in the bladder wall (Figure 3). We repaired the hole using this method to suture all layers of bladder wall with 2-0 absorbable thread. We replaced a new catheter (18F Foley catheter) and kept it in the bladder to drain urine. Finally, we washed the abdominal cavity with normal saline, and closed the abdominal cavity with an indwelling drainage tube. It is a pity that the patient chose to continue the indwelling catheter because of poor cardiopulmonary function and unable to withstand partial prostatectomy. After more than a month, the patient recovered and left the hospital.

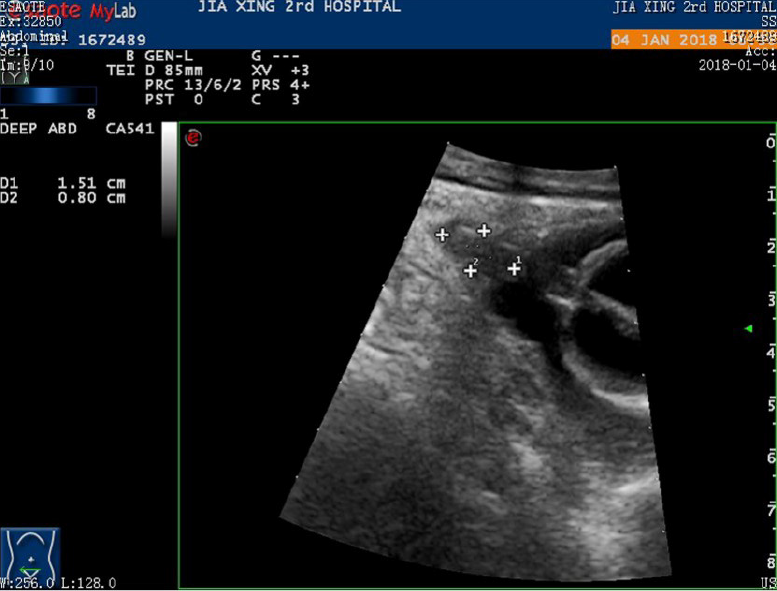

After reviewing the patient’s previous medical records, we found that 1 year prior, the patient underwent an ultrasound examination showing that the end of the catheter was embedded in the mucosal layer of the bladder (Figure 4). Therefore, the bladder perforation in this patient may have been caused by the chronic compression of the urinary catheter against the bladder wall. This bladder perforation may not occur if the ultrasound results were taken seriously and appropriate action had been taken by the physician.

In this case, the patient had a bladder perforation combined with peritonitis due to a long-term indwelling urinary catheter. Although it was not a spontaneous rupture of the bladder, it is rare in clinical practice. With the aging of the population, there is an increasing number of elderly and high-risk patients with long-term indwelling urinary catheters. Long-term indwelling urethral catheters are associated with many risks, including urinary tract infection, catheter shedding, difficult extubation, urethral stricture and bladder mucosal damage, among others. Serious cases lead to urethral perforation, which is extremely rare[5]. This is because the balloon catheter is left in the bladder normally. Long-term continuous catheterization causes the bladder to be nonfilled, which reduces the bladder volume. The top of the catheter becomes embedded in the bladder mucosa, resulting in local ischemia, mucosal damage and chronic inflammation, which can lead to bladder structure abnormalities, bladder wall necrosis and perforation.

In this case, an ultrasound examination showed that the urethral catheter end was embedded into the mucosal layer of the bladder 1 year before. It is not clear whether this injury was the site of the perforation. It should be noted that patients who require long-term indwelling catheterization tend to be frail elderly patients with poor reactivity and insensitivity to pain. In the early stage, the bladder perforation is small, the pressure in the bladder is low and the speed and volume of urine outflow are small. Therefore, the patient often has no obvious symptoms, the disease progresses slowly and it is easy to delay treatment resulting in diffuse peritonitis, which is life-threatening[6,7].

In this case, there was still a large amount of urine outflow through the catheter, and diffuse peritonitis had occurred indicating that the bladder perforation of this patient was a chronic process. Therefore, it is difficult to diagnose such cases and led to a misdiagnosis of digestive tract perforation. Schein et al[8] considered the diagnosis of spontaneous bladder perforation to be challenging and usually made during open surgery[8]. A patient with T1 paraplegia had a bladder perforation due to intermittent self-catheterization reported by Martin et al[9]. This case highlighted the fact that a preoperative diagnosis of bladder perforation in T1 paraplegics with no abdominal sensation is very difficult[9], and the delay in diagnosis and treatment is the main cause of death in patients with bladder perforation[10,11].

Some researchers have suggested that cystostomy should be performed in patients with a long-term indwelling catheter. The possible complications of long-term indwelling catheters can be avoided. However, the proportion of patients with cystostomy is very low clinically, which may be related to the high age of most patients and the high risk of operation. Some have also proposed that the urethral catheter should be intermittently closed in the process of catheterization so that the bladder is in the filling state for most of the time thus reducing the pressure of the urethral catheter on the bladder mucosa.

Regular replacement of urinary catheters can reduce urinary tract infections and avoid compression of the bladder mucosa in the same area, but the optimal time to replace urinary catheters is still unclear and needs to be confirmed by more clinical studies. The use of a catheter with a smooth, flexible end can also reduce injury to the bladder wall. When the patient has mild symptoms or the bladder mucosa is found to be slightly injured by ultrasound examination, timely treatment should be provided to avoid misdiagnosis and delay the disease[12]. In this case, if a preoperative ultrasound examination[13] or cystography[14] is performed, then it may be helpful to locate the perforation during surgery. Of course, the possibility of a bladder perforation should be considered in patients with this kind of long-term indwelling catheter combined with peritonitis.

For patients with long-term indwelling catheters, there is a possibility of bladder perforation, which needs to be dealt with quickly.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tander B, Tenreiro N, Tsujinaka S S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Matlock KA, Tyroch AH, Kronfol ZN, McLean SF, Pirela-Cruz MA. Blunt traumatic bladder rupture: a 10-year perspective. Am Surg. 2013;79:589-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Grzybowski JS, Simon ER, Borden SB. Iatrogenic Bladder Perforation During Laparoscopy: Revisiting the "Catheter Bag" Sign: A Case Report. A A Pract. 2019;13:423-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Johnsen NV, Young JB, Reynolds WS, Kaufman MR, Milam DF, Guillamondegui OD, Dmochowski RR. Evaluating the Role of Operative Repair of Extraperitoneal Bladder Rupture Following Blunt Pelvic Trauma. J Urol. 2016;195:661-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sawalmeh H, Al-Ozaibi L, Hussein A, Al-Badri F. Spontaneous rupture of the urinary bladder (SRUB); A case report and review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;16:116-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Chan VSH, Kwok WM, Cheung SCW. Catheterised hutch diverticulum masquerading as intraperitoneal bladder perforation. Hong Kong Med J 2019; 25: 159.e1-159. e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pohlman GD, Wilcox DT, Hankinson TC. Erosive bladder perforation as a complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt with extrusion from the urethral meatus: case report and literature review. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2011;47:223-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rausch S, Amend B, Adam M, Stenzl A, Bedke J. [Urinary bladder injuries. Diagnosis and treatment]. Urologe A. 2016;55:466-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schein M, Weinstein S, Rosen A, Decker GA. Spontaneous rupture of the urinary bladder--delayed sequel of pelvic irradiation. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1986;70:841-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Martin J, Convie L, Mark D, McClure M. An unusual cause of abdominal distension: intraperitoneal bladder perforation secondary to intermittent self-catheterisation. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Anderson PA, Rickwood AM. Detrusor hyper-reflexia as a factor in spontaneous perforation of augmentation cystoplasty for neuropathic bladder. Br J Urol. 1991;67:210-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Couillard DR, Vapnek JM, Rentzepis MJ, Stone AR. Fatal perforation of augmentation cystoplasty in an adult. Urology. 1993;42:585-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Karim T, Topno M. Bedside sonography to diagnose bladder trauma in the emergency department. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3:305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wu TS, Pearson TC, Meiners S, Daugharthy J. Bedside ultrasound diagnosis of a traumatic bladder rupture. J Emerg Med. 2011;41:520-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Johnsen NV, Dmochowski RR, Guillamondegui OD. Clinical Utility of Routine Follow-up Cystography in the Management of Traumatic Bladder Ruptures. Urology. 2018;113:230-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |