Published online Jan 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i2.362

Peer-review started: November 9, 2019

First decision: November 19, 2019

Revised: November 30, 2019

Accepted: December 14, 2019

Article in press: December 14, 2019

Published online: January 26, 2020

Processing time: 68 Days and 15.8 Hours

Sacrococcygeal hernia is a very rare condition that is usually secondary to sacrococcygectomy, and its ideal treatment regimen is unclear. Herein, we report a case of sacrococcygeal hernia occurring in a patient who had no history of sacrococcygeal operation, present the operative procedures of mesh repair via a combined laparoscopic and sacrococcygeal approach that has not been described, and discuss our experience in diagnosis and treatment with a review of the literature.

A 54-year-old woman who chiefly complained of a 10-year history of a reversible bulge in her right sacrococcygeal region was admitted to our hospital. The physical examination revealed a bulge in the right sacrococcygeal region upon standing, which disappeared in the prone position but relapsed when performing the Valsalva manoeuvre. Computed tomography displayed an abnormality in the structure of the tissues between the midline of the sacrococcygeal region and the right gluteus muscle. The patient was diagnosed with sacrococcygeal hernia and received hernia repair with mesh through a combined laparoscopic and sacrococcygeal approach. On laparoscopy, the rectum was dissected posterolaterally, and a defect was identified in the right anterior sacrococcygeal region through which part of the rectum protruded. This was followed by the placement of a self-gripping polyester mesh via a sacrococcygeal approach. There were no postoperative complications. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 7 and was followed for more than 6 mo with no recurrence.

Laparoscopic mesh repair is recommended as a priority of surgical options for sacrococcygeal hernias, while choosing a self-gripping mesh can help avoid the risk of presacral vessel injury by reducing suture fixation.

Core tip: A 54-year-old woman was diagnosed with a sacrococcygeal hernia. The patient received hernia repair with a mesh through a combined laparoscopic and sacrococcygeal approach. On laparoscopy, the rectum was dissected posterolaterally to return the hernia content and to expose the defect in the right anterior sacrococcygeal region. This was followed by the placement of a self-gripping polyester mesh via a sacrococcygeal approach. There were no postoperative complications, and the patient was followed for more than 6 mo with no recurrence. Our experience demonstrates that laparoscopic mesh repair can serve as a priority of surgical options for sacrococcygeal hernias, while choosing a self-gripping mesh can help avoid the risk of presacral vessel injury by reducing suture fixation.

- Citation: Dong YQ, Liu LJ, Fu Z, Chen SM. Mesh repair of sacrococcygeal hernia via a combined laparoscopic and sacrococcygeal approach: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(2): 362-369

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i2/362.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i2.362

Sacrococcygeal hernia is a very rare condition with an external bulge in the body region between and flanking the sacrum and coccyx. Due to the support and stabilization of the sacrococcyx and its attached muscles, a sacrococcygeal hernia is generally secondary to sacrococcygectomy, especially in patients with a postoperative infection or repeated operations. Surgical repair is the treatment of choice, and prosthetic mesh is usually used in patients at the first occurrence. The sacrococcygeal approach and the abdominal approach have been adopted for mesh repair, while evidence on which approach is better is inconclusive. In addition, the introduction of laparoscopy in recent years has also added new factors of consideration to the selection of the surgical approach. All these factors make it difficult for the surgeon to obtain decisive guidance from the previous literature when encountering such cases. Herein, we report a case of sacrococcygeal hernia without a surgical history of the sacrococcygeal region that was successfully treated by mesh repair via a combined laparoscopic and sacrococcygeal approach, which has not been described before. For this rare disease, the simultaneous application of the two surgical approaches in one case may help us more intuitively understand and compare the similarities and differences between the two approaches. We also review the published literature and discuss the diagnosis and treatment of sacrococcygeal hernias.

A 54-year-old woman with a 10-year history of a reversible bulge in her right sacrococcygeal region presented to our outpatient clinic.

The bulge disappeared in the prone position and appeared when standing. In addition, she complained of long-term constipation. There was no regional or abdominal pain, no nausea and vomiting, and no abdominal distention in her course of disease. In the past ten years, she had not received any relevant examination or treatment. Noticing that the bulge was increasing in size gradually, she came to seek treatment and then was admitted to our inpatient ward.

The patient denied a history of chronic diseases or infectious diseases. She had a history of caesarean section 17 years ago but no trauma or blood transfusion. She also had no known drug or food allergies.

A bulge in the right sacrococcygeal region was revealed upon standing, which was approximately 8 cm × 8 cm in size and soft in palpation with no tenderness (Figure 1). In the prone position, the bulge returned spontaneously but relapsed when performing the Valsalva manoeuvre. The abdomen was flat, with an old surgical scar in the hypogastric zone.

Laboratory examinations performed in the ward included routine blood tests and biochemistry examinations. All results were within normal limits.

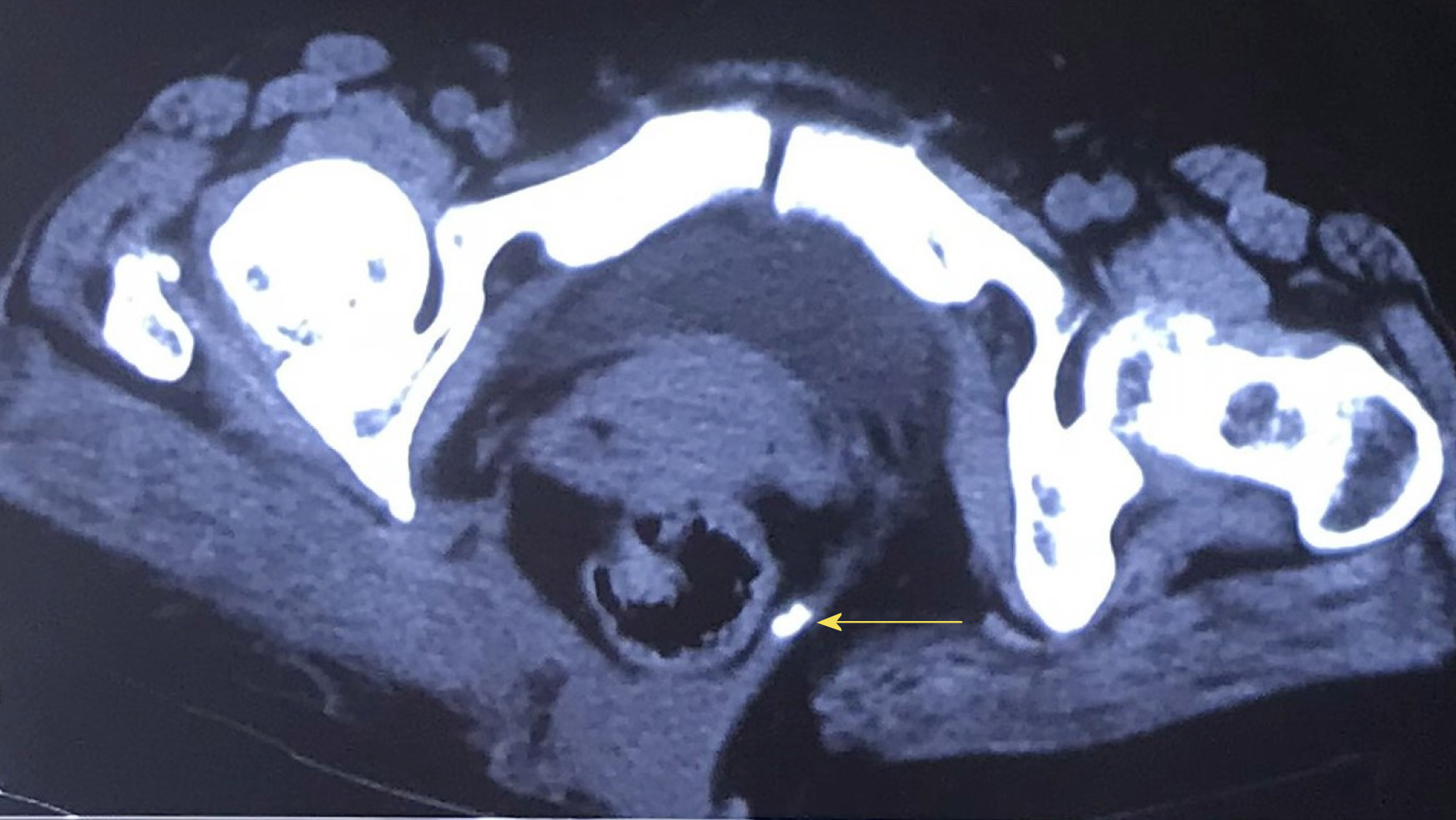

Doppler ultrasound detected a bulge in the bowel when there was an increase in abdominal pressure, which returned to the abdominal cavity after loosening. Computed tomography confirmed the Doppler ultrasound finding of rectal herniation and displayed an abnormality in the structure of the tissues between the midline of the sacrococcygeal region and the right gluteus muscle (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with hernia in the right sacrococcygeal region.

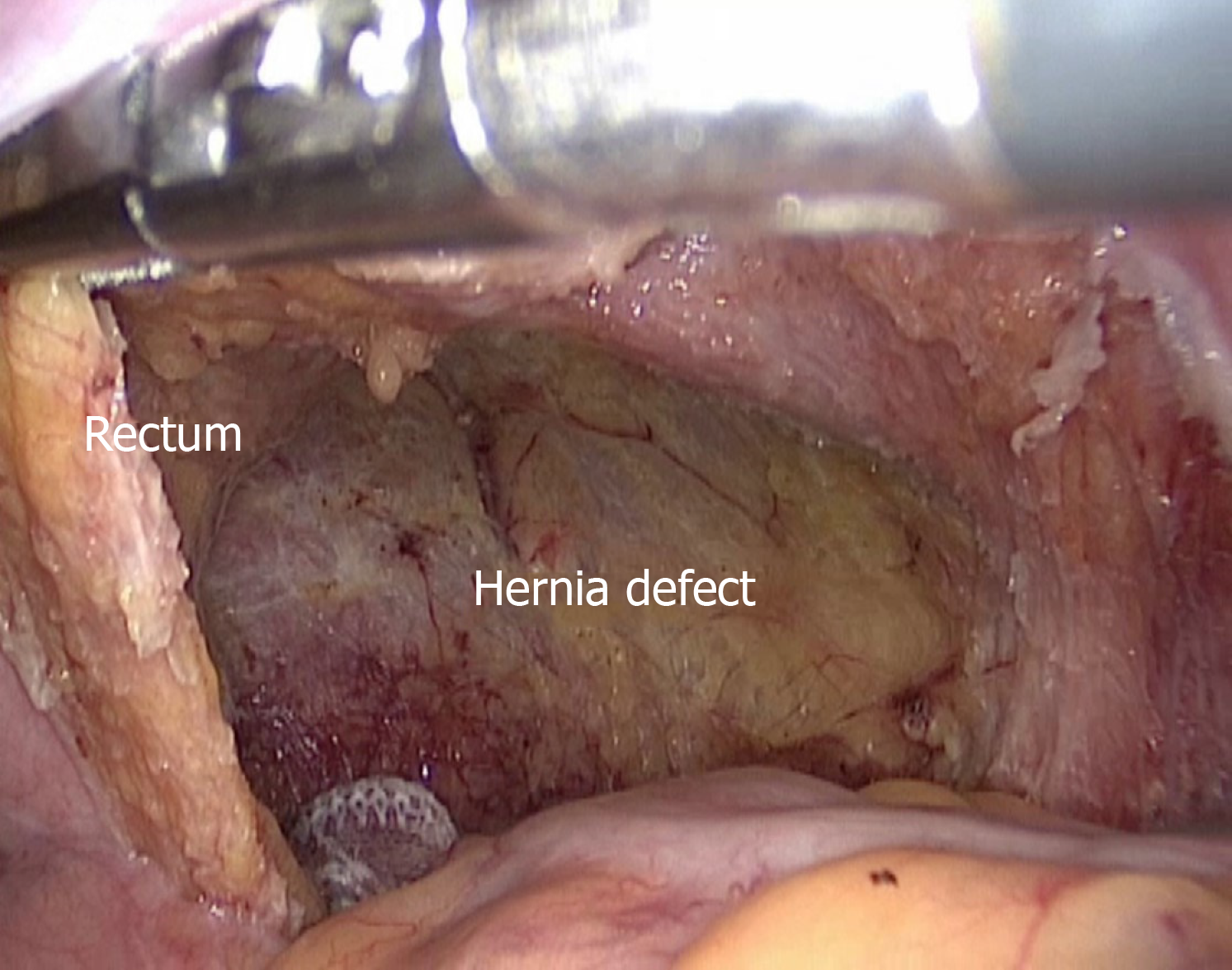

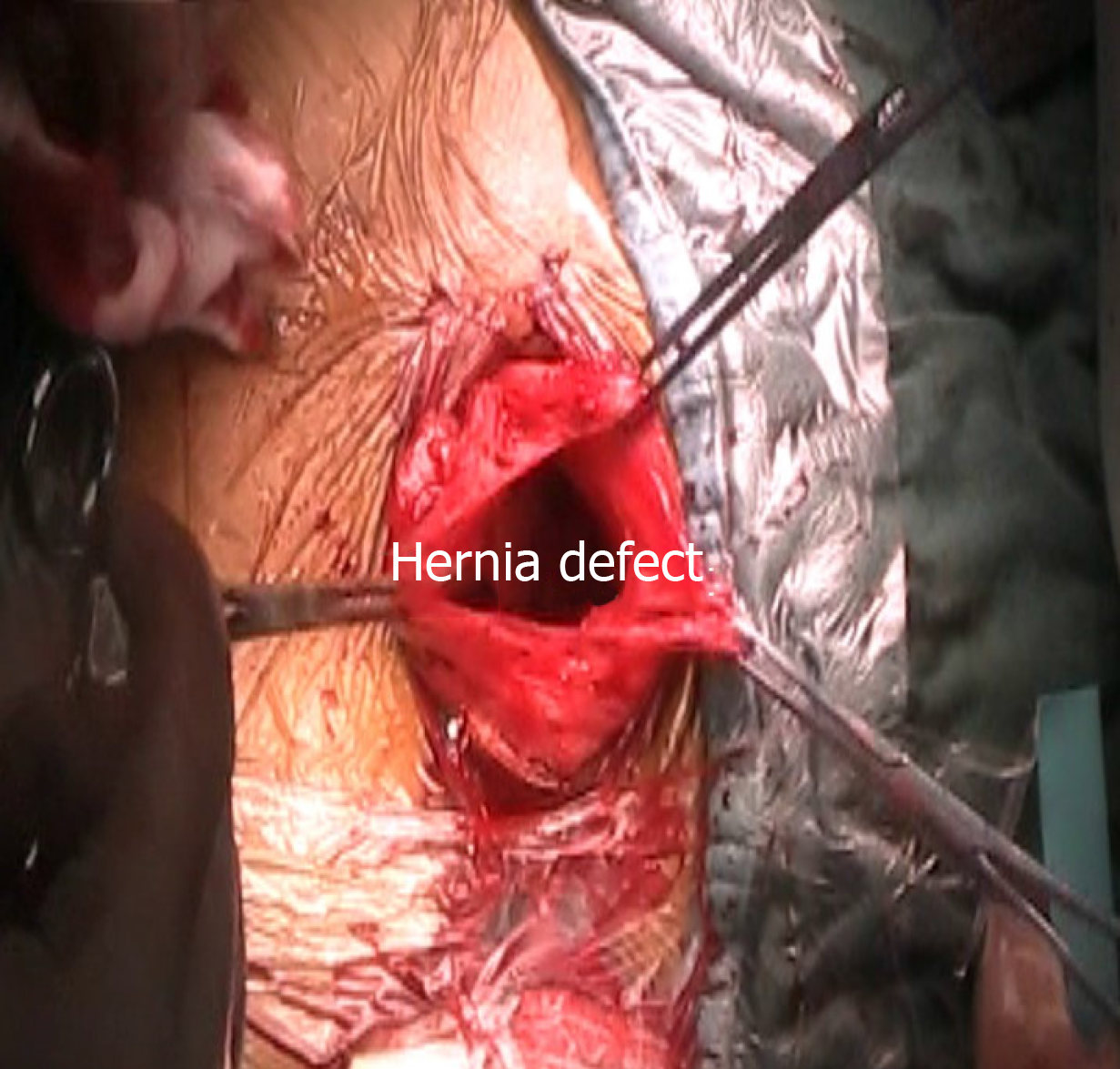

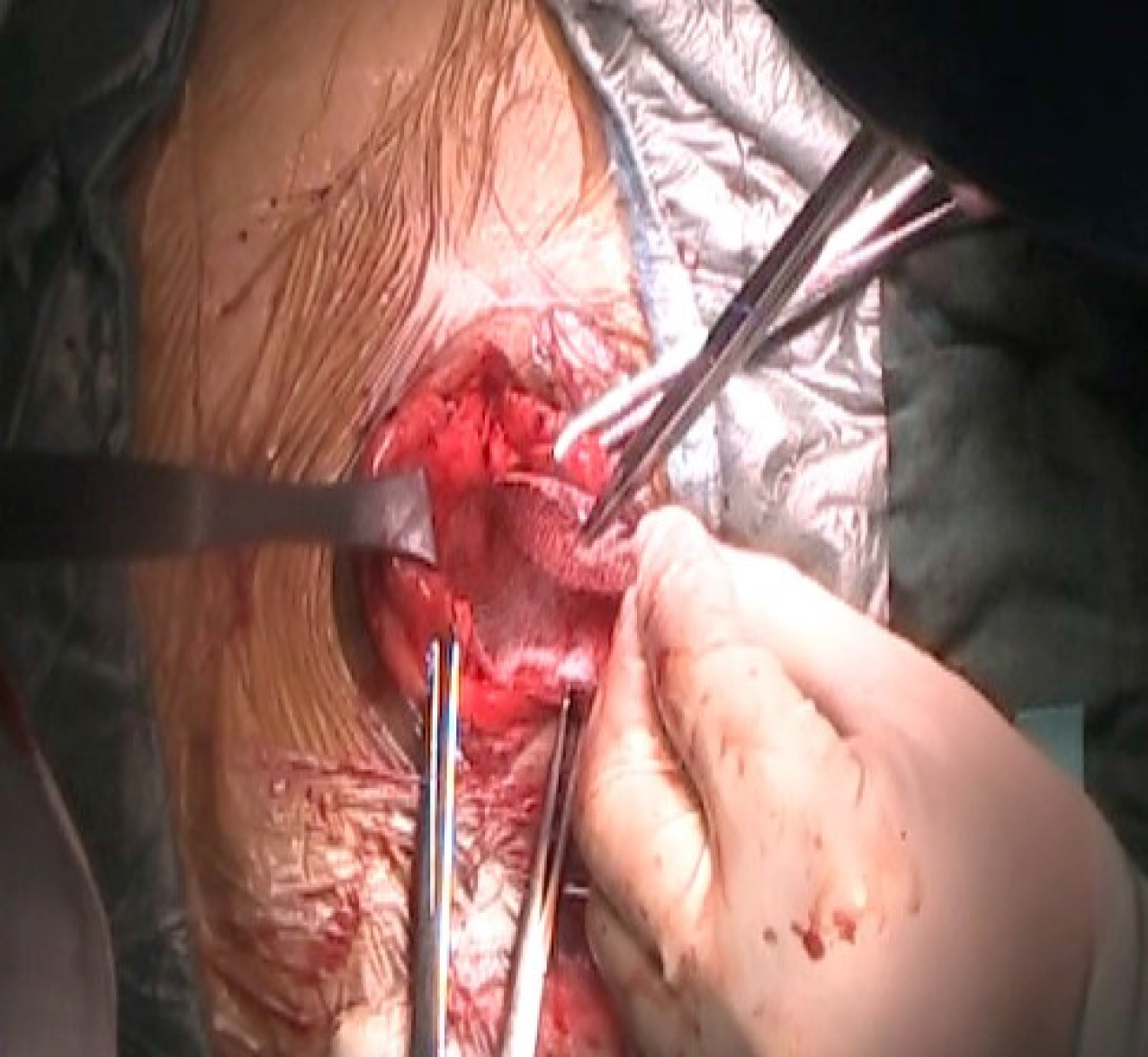

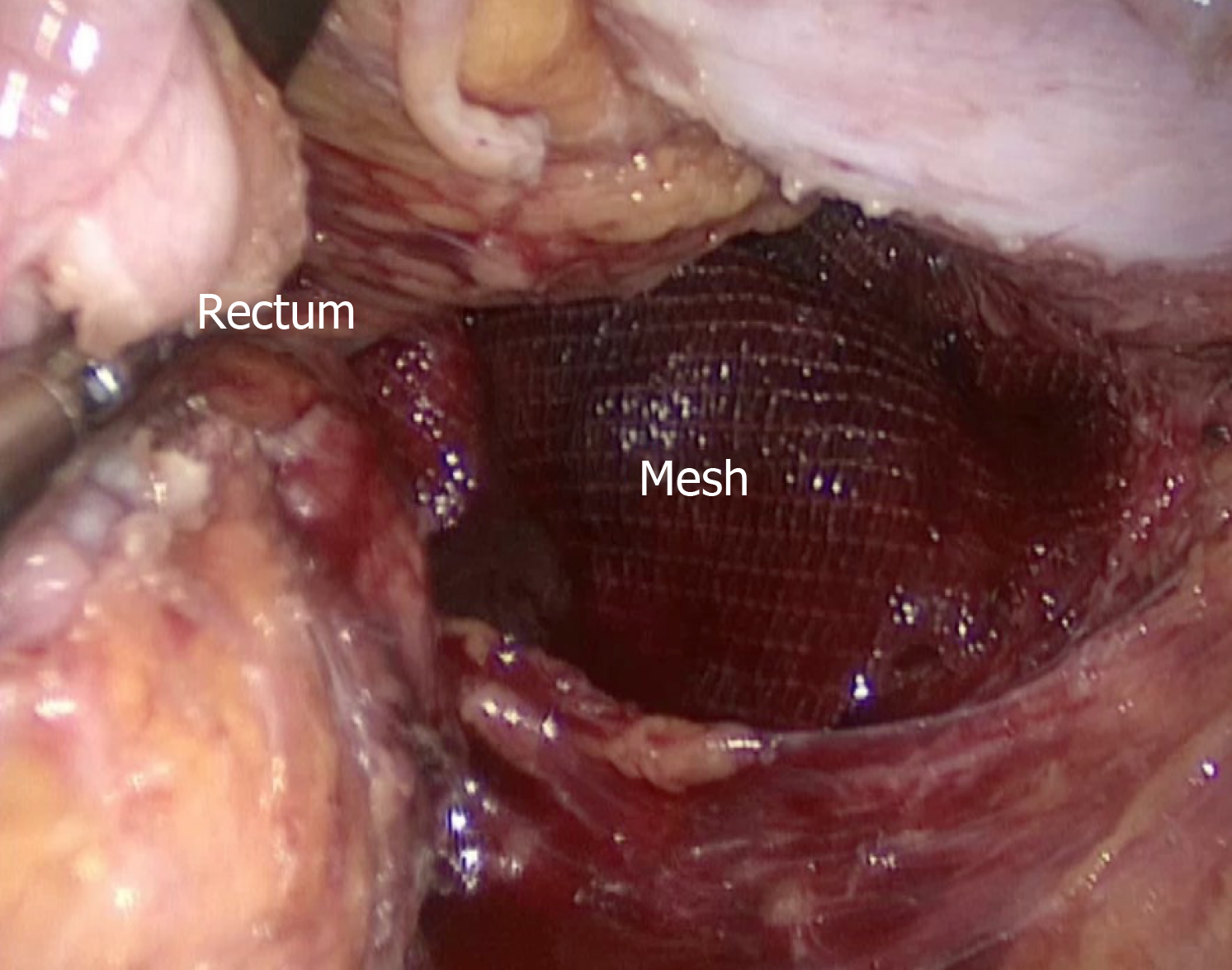

After bowel preparation, the patient received sacrococcygeal hernia repair with a mesh via a combined laparoscopic and sacrococcygeal approach under general anesthesia. During surgery, the lithotomy position was taken first. After the establishment of pneumoperitoneum at 10-12 mmHg, five trocars were inserted into the abdominal cavity: One in the infraumbilical area, two in the left lower quadrant, and two in the right lower quadrant. Under laparoscopy, the sigmoid colon was mobilized, and thereafter, the rectum was dissected posterolaterally along the mesorectum down to the plane of the levator ani muscle. In the right anterior sacrococcygeal region, a defect approximately 6 cm × 6 cm in size was identified, through which part of the rectum protruded (Figure 3). Subsequently, the patient’s position was changed to prone. An incision was made in the right paramidline of the sacrococcygeal region. After incising the subcutaneous tissues, a loose fascia was displayed. The hernia defect was visualized after opening the fascia (Figure 4). Then, a properly sized self-gripping polyester mesh (ProGrip™; Covidien) was placed deep into the defect and intermittently sutured to the sacrococcygeal periosteum medially and to the dense aponeuroses laterally (Figure 5), followed by overlapping suture of the fascia. A negative pressure drainage tube was applied on the surface of the mesh before the incision was closed. Last, the patient’s position was changed to supine again. Via laparoscopy, the implanted mesh was inspected for accommodation in a good location, and the incision of the pelvic peritoneum was closed (Figure 6). Likewise, a pelvic drainage tube was applied, followed by the closure of all trocar sites.

The patient recovered smoothly after surgery. The pelvic and sacrococcygeal drainage tubes were removed on postoperative days 4 and 5, respectively. There were no local or systemic complications, and the wounds healed well. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 7. At the time of discharge, no relapsing bulge was found either in the standing position or when performing the Valsalva manoeuvre (Figure 7). The patient was followed for more than 6 mo with no recurrence based on clinical examinations.

The present case report describes a sacrococcygeal hernia. It is extremely rare for the rectum to herniate through the sacrococcygeal region due to strong support of the sacrococcyx as well as its attached muscles. A review of the literature revealed that sacrococcygeal hernia is a rare complication after an operation in the sacrococcyx for a tumour or coccygodynia, especially in patients with repeated operations or a postoperative wound infection, increased intraabdominal pressure, and old age[1]. However, our middle-aged patient had no previous sacrococcygeal surgery, and it was found that weakness of the coccygeus caused herniation during the operation, indicating that a primary disorder of a muscle can also be a rare cause of sacrococcygeal hernia.

The clinical manifestations of sacrococcygeal hernia are mainly a reversible bulge as well as anatomic defects in the sacrococcygeal region. The hernia usually involves the rectum and occasionally involves the small intestine[1]. Due to the large defect in general and the relative fixity of the rectum, incarceration is less likely to happen. The patient can also have local pain at different levels, especially when sitting. Of particular note is that the new constipation is a common symptom and can be the most important complaint, which is considered to be caused by an abnormal rectal position and a change in the anorectal angle[2]. Imaging examinations are usually required, mainly including computed tomography, which is most commonly used to help judge hernia contents and defective anatomic structures, and magnetic resonance imaging, which is more helpful in showing soft tissue defects.

Since the sacrococcygeal region lacks strong aponeurotic tissues and the dense hernia ring of the sacrococcygeal hernia is difficult to approximate even if it exists, fascial closure is not feasible for sacrococcygeal hernias[3]. According to the literature, mesh repair is the preferred treatment option with basically reliable outcome. As for mesh selection, polypropylene and polytetrafluoroethylene[4] are the two most commonly used repair materials. In our opinion, the pathogenesis, anatomic site, and fixing requirement are three main influencing factors on the choice of mesh in such rare hernias. This case was to repair bulging, and a surgical mesh was to be placed into the extraperitoneal space of pelvic floor with minimal risk of intestinal erosion, and meanwhile in order to avoid injury of presacral venous plexus, a polyester mesh with polylactic acid grips was eventually chosen to reduce fixation with suture. In cases of severe defects, however, complex meshes may have to be considered, as this allows repair of the hernia with significant pelvic defects. For example, two crisscross meshes were transabdominally applied to repair the hernia defect and reconstruct the pelvic floor after joint excision of the sacrum below S1, anus, and rectum[5]. And more recently, the use of a biological mesh for a patient at risk of an infection has also been reported, and the patient was followed for 2 mo with no recurrence[6]. Muscle flaps are mainly used for recurrent patients after the failure of mesh repair or patients with local contamination. According to the patient’s condition, a gluteus maximus muscle flap, a tensor fasciae latae graft or a de-epithelialised rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap has been used. A gluteus maximus muscle flap was designed by freeing the muscle from the sacrum and iliac crest, and then the bilateral muscle flaps were transposed inferiorly and sutured in the midline to repair the defect[3]. A tensor fasciae latae graft was used in an onlay manner covered by a posterior fasciocutaneous thigh flap[7]. And a de-epithelialised rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap could not only eliminate the dead space within vascularized muscle tissue, but also provide adequate mechanical support similar to a prosthetic mesh with de-epithelialised dermis[1].

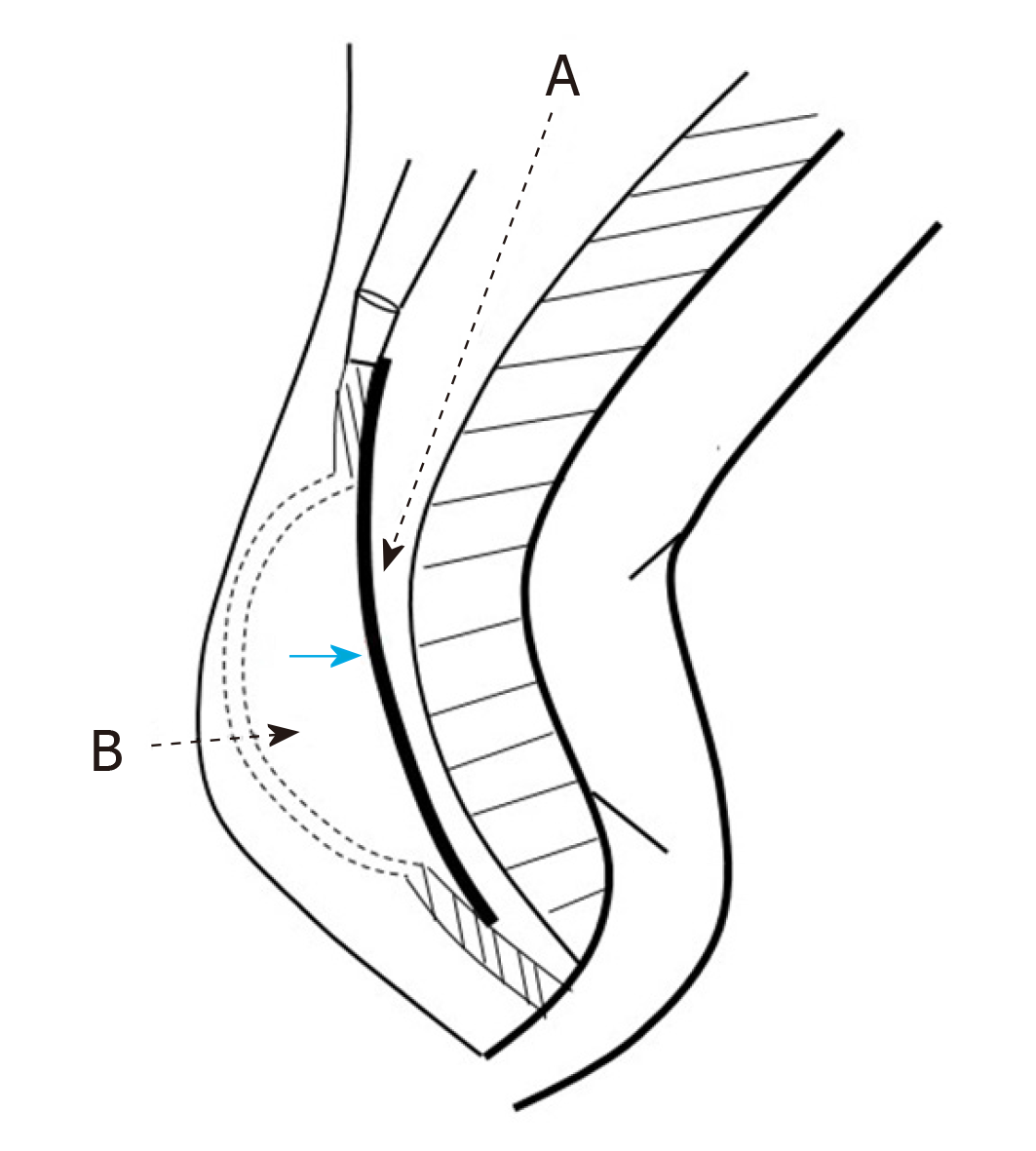

Due to its rarity, the preferred operative approach for a sacrococcygeal hernia has not yet been determined. Even for a hernia specialist, there is little chance of treating a sacrococcygeal hernia patient throughout the entire career. With reference to the treatment experience for perineal hernia, three alternative surgical approaches have been proposed: Trans-sacrococcygeal, trans-abdominal, or a combination of the two. Without entering the abdominal cavity, the sacrococcygeal procedure allows an easy, direct reach to the hernia defect by incising the skin and subcutaneous tissues. It should be noted that the loose fascia encountered through this approach is practically indistinguishable from the bowel wall, and injury to the rectum should be avoided during dividing, which can be done by inserting fingers through the anus into the rectum for confirmation. Despite a larger incision, the sacrococcygeal approach is still believed to be less traumatic considering its shallow anatomic layer[2]. The trans-abdominal approach requires mobilization of the sigmoid colon and posterolateral dissection of the rectum along the plane of the mesorectum to expose the hernia defect. It facilitates dissection and a reduction in the hernia contents, allows better identification of the hernia defect, and is convenient for placement of the mesh under direct vision. The mesorectum can keep the rectum away from direct contact with the mesh, but the incision of the peritoneum of the pelvic floor should be closed. In addition, there is less chance of an infection of the abdominal wound than that of the sacrococcygeal wound[8]. However, the procedure via the abdominal route demands a higher surgical technique of the operator and may yield a higher morbidity. The combined sacrococcygeal and abdominal approach achieves the best operative exposure among the three approaches, which guarantees a precise location and reliable repair of the hernia and is thus suitable for complicated or uncertain conditions. In the present case, it was proved that the mesh could be placed in the same correct position through both the sacrococcygeal and abdominal routes, assuming that the operative layer was reached based on the description of our case report (Figure 8). In the past ten years, the application of laparoscopic skills has brought about a new outlook for the abdominal approach. Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy is characterized by less analgesia, a quicker return of bowel function, and a shorter hospital stay with a good cosmetic effect[9]. Laparoscopy also makes the pelvic operation much easier and can thus substitute for laparotomy in the absence of contraindications. In this case, we did not fix the mesh laparoscopically because we thought that the suturing via the sacrococcygeal approach was more convenient and safe, with less concern about injury of the presacral venous plexus. But through the surgical experience of this case, we think that totally laparoscopic surgery can be a priority once the surgeons are familiar with the anatomy of the anterior sacrum and skilled at suturing under laparoscopy. Last, while we already have some experience with treatment, as described above, we know little about recurrence following different approaches. And for recurrent cases, a surgical approach different from the one before may be considered.

After treatment, the curative effect is mainly evaluated based on clinical examinations. The first is to observe whether the sacrococcygeal bulge disappears without recurrence. Then, it is necessary to inquire whether the pain has relieved and whether defecation dysfunctions, mainly constipation, have returned to normal. However, defecation dysfunctions may be irrelevant to the hernia itself sometimes and thus should be distinguished carefully before the operation.

Sacrococcygeal hernia can occasionally occur in patients with primary weakness of pelvic floor muscles. Laparoscopic mesh repair is recommended as a priority of its surgical options, while choosing a self-gripping mesh can help avoid the risk of presacral vessel injury by reducing suture fixation.

We thank Dr. Yong Wang and Dr. Yuan Li for their technical assistance.

| 1. | Miranda EP, Anderson AL, Dosanjh AS, Lee CK. Successful management of recurrent coccygeal hernia with the de-epithelialised rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:98-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zook NL, Zook EG. Repair of a long-standing coccygeal hernia and open wound. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:96-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | García FJ, Franco JD, Márquez R, Martínez JA, Medina J. Posterior hernia of the rectum after coccygectomy. Eur J Surg. 1998;164:793-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Atkin G, Mathur P, Harrison R. Mesh repair of sacral hernia following sacrectomy. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:28-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hoexum F, Vuylsteke RJ. Repair of a coccygeal hernia with a biological mesh. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;6C:259-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Maguina P, Kalimuthu R. Posterior rectal hernia after vacuum-assisted closure treatment of sacral pressure ulcer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:46e-47e. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kumar A, Reynolds JR. Mesh repair of a coccygeal hernia via an abdominal approach. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82:113-115. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Dugani S, Tran DQ, Finlayson RJ. Incidental detection of bowel herniation with ultrasonography and fluoroscopy during a caudal block. Can J Anaesth. 2011;58:551-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Feretis M S-Editor: Wang YQ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu MY