Published online Oct 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4652

Peer-review started: April 15, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Revised: July 28, 2020

Accepted: August 25, 2020

Article in press: August 25, 2020

Published online: October 6, 2020

Processing time: 165 Days and 21.4 Hours

Gemcitabine is a chemotherapy agent with relatively low toxicities, as a valid option for elderly patients with underlying diseases. Gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicities are rare and various, ranging from self-limited episodes of bronchospasm to fatal, progressive, severe, interstitial pneumonitis and respiratory failure. Intravesical gemcitabine instillations are commonly used to reduce recurrence or progression for non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer or urothelial cancer. Few severe toxicities have been reported for the intravesical instillation is assumed to be completely separated from the systemic circulation.

A 67-year-old patient received 30 cycles of intravesical gemcitabine instillation after transurethral resection and developed a 1-wk fever, cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea. After a thorough checkup, bilateral consolidation and infiltration of the lungs were documented and a percutaneous lung biopsy confirmed organizing pneumonia after treatment with broad-spectrum empirical antibiotics failed. Tapered corticosteroids were administered, and pulmonary toxicity gradually resolved.

Gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicities present with various manifestations. In spite of the rare pulmonary involvement by the intravesical gemcitabine instillation, health care professionals who administer gemcitabine chemotherapy in this way should monitor for gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicities, particularly in patients with high-risk factors.

Core Tip: Gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicities are rare and various, ranging from self-limited episodes of bronchospasm to fatal, progressive, severe, interstitial pneumonitis and respiratory failure. Intravesical gemcitabine instillations are commonly used to reduce recurrence or progression for non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer or urothelial cancer. Few severe toxicities have been reported for the intravesical instillation is assumed to be completely separate from the systemic circulation. In spite of the rare pulmonary involvement by the intravesical gemcitabine instillation, health care professionals who administer gemcitabine chemotherapy in this way should monitor for gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicities, particularly in patients with high-risk factors.

- Citation: Zhou XM, Wu C, Gu X. Intravesically instilled gemcitabine-induced lung injury in a patient with invasive urothelial carcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(19): 4652-4659

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i19/4652.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4652

Gemcitabine, a nucleoside analog, is currently the standard chemotherapy for solid tumors, including non–small cell lung cancer and colonic, pancreatic, and bladder cancers[1,2]. Gemcitabine is generally well tolerated with few side effects, with gastrointestinal symptoms and myelosuppression most commonly occurring[3,4]. Nevertheless, pulmonary toxicities are rare and various, ranging from self-limited episodes of bronchospasm to fatal, progressive, severe, interstitial pneumonitis and respiratory failure[1,2,5]. Although in vivo experiments revealed the acute and delayed toxicity of gemcitabine administered by lung perfusion[6,7], most of the pulmonary toxicities and injuries were reported to be caused by systemic chemotherapy resulting from intravenous administration[1]. For the treatment of invasive urothelial carcinoma or bladder carcinoma, gemcitabine is given by 1- or 2-h intravesical instillation. Topical adjuvant chemotherapy is characterized by low systemic peak plasma levels; therefore, it is believed to rarely cause systemic side effects[8]. Thrombocytopenia and neutropenia were the only documented systemic grade 3 side effects in a literature review[8,9]. In this report, we describe a case of invasive urothelial carcinoma treated with a single gemcitabine intravesical instillation associated with severe gemcitabine-induced lung injury.

Fever, cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea for one week after 30 cycles of gemcitabine instillation as the standard topical chemotherapy for invasive urothelial carcinoma.

A 67-year-old man was referred to the emergency department for the fever, cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea for one week. The peak temperature was 38 °C. The cough was productive with recurrent sticky bloody sputum. Dyspnea was progressive with dyspnea at rest on admission.

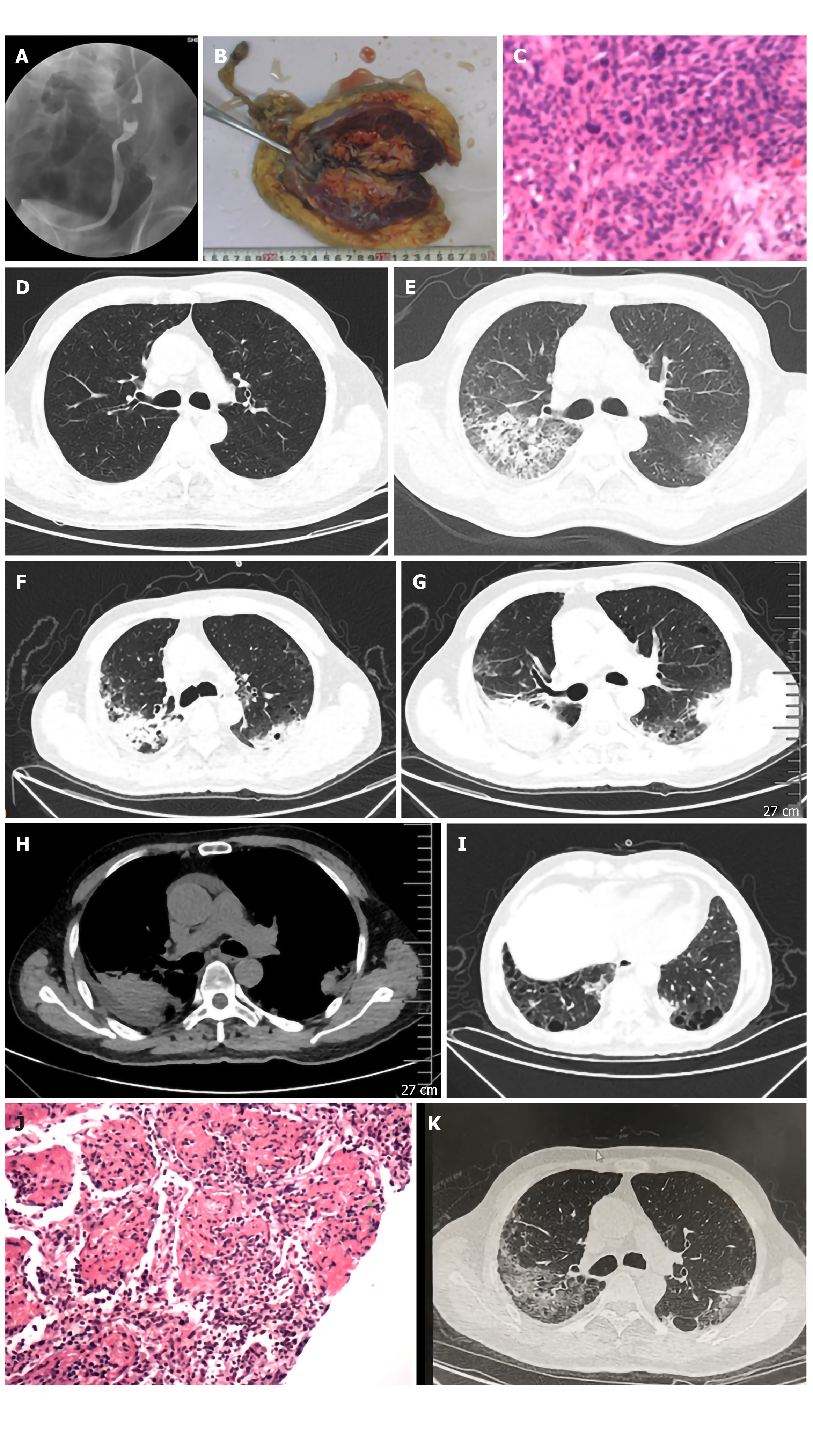

The patient presented with a history of asymptomatic hematuria for 3 mo and a left urothelial mass. The perioperative screening examination and staging indicated a left urothelial obstruction via the ureterography (Figure 1A) and a urothelial tube had been placed for urine drainage. Laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy with bladder cuff excision was performed and the pathological examination revealed invasive urothelial carcinoma with infiltration to the muscular layer (Figure 1B and C). Part of the vesical and ureteric epithelial cells exhibited atypical hyperplasia. The patient received the standard topical chemotherapy with gemcitabine via intravesical instillation at a dosage of 1.0 g per 1.75 m2 every 2 wk. During the period of 30 cycles of gemcitabine instillation, no side effects occurred.

The patient’s medical history was significant for a 40 pack-year smoking history.

On examination, the patient exhibited decreased bilateral breath sounds and bilateral fine crackles.

During the admission checkup, a pharyngeal swab was taken and tested by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction for influenza, producing a negative result. Tests for autoimmune-disease antibodies were all negative, with a ferritin level of 270.9 ng/mL (normal range: 11-336.2 ng/mL) and an IgG4 level of 0.764 g/L (normal range: 0.012-2.01 g/L). Other laboratory examination results were as follows: White blood cells 8.08 × 109/L, neutrophils 5.8 × 109/L (72.3%), lymphocytes 1.1 × 109/L (13.8%), C-reactive protein (CRP) 87.80 mg/L (normal range: ≤ 8 mg/L), interleukin-6 24.73 pg/mL (normal range: ≤ 8 pg/mL), creatinine 108.6 µmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 5.07 mmol/L, and interferon-gamma release assay was negative. Blood gas analysis showed hypoxemia with a partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) of 66 mmHg, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) of 38 mmHg, and pH of 7.44. During empirical antibiotic treatment, the patient showed no improvement. On the eighth day after admission, his respiratory distress became worse, with PO2 and PCO2 decreasing to 48 mmHg and 34 mmHg, respectively. A recurrent, sticky hemoptysis, cough, and newly emerging fever began over a 3-d period. The peak temperature was 38.4 °C. The CRP level increased to 130 mg/L along with the appearance of respiratory distress and fever, but there was no obvious change in routine blood test results. Before that, all the tests, including sputum and blood smears for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, mycoplasma, and chlamydia, were negative.

Intravesically instilled gemcitabine-induced lung injury.

In response to the patient’s worsening conditions, methylprednisolone 40 mg every 12 h was given to the patient on the 11th day. Three days later, the methylprednisolone was reduced to 40 mg/d taken orally.

The fever subsided and the respiratory distress was relieved thereafter. Three days later, the CRP decreased to 28.1 mg/L, with a PO2 of 61 mmHg (nasal cannula 2 L/min). A CT scan performed on the 11th day showed worsening of the patchy infiltration with more consolidated foci. A percutaneous lung biopsy was carried out for definitive diagnosis (Figure 1F-I). Histologic examination revealed organizing pneumonitis (Figure 1J) and the methylprednisolone was reduced to 40 mg/d taken orally. A repeated CT scan 17 d later showed slight improvement (Figure 1K) and an increased PO2 of 68 mmHg; therefore, the patient was discharged. One month later, obvious absorption of lung foci was observed on a CT scan.

It is reported that gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity is a relatively uncommon complication with significant morbidity and mortality, ranging from mild to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. However, the incidence varies quite widely from 0.02%[10] to 42%[1,11], whereas the incidence of most severe cases have been reported to be 0.002%[12,13] to 0.3%[13,14]. This variety exists for several reasons. The first one might be reporting bias, because a 10-fold increase was found in the clinical trials compared with the incidence in the spontaneous report in daily practice in one literature review involving 40 cases[5], which calls for more emphasis on the concern and the underestimate for pulmonary toxicity in the clinical use of gemcitabine. The highest incidence of gemcitabine-associated lung injury occurred in patients with Hodgkin disease receiving multidrug chemotherapeutic regimens that included gemcitabine and bleomycin (which has an especially high incidence of pulmonary fibrosis)[11]. Second, when it comes to gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity in different cancers, the incidence varies as well. A total of 178 reports of gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity were reviewed and the diagnoses were specified, revealing that the incidence of pulmonary toxicity occurred mostly in lung cancer (52%), followed by pancreatic (16%) and breast (6%) cancers[1]. Often, lung cancers are accompanied by previous tobacco exposure or underlying lung disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, or occupational lung diseases which might be risk factors for developing pulmonary toxicities. Nevertheless, other studies that included many patients with digestive organ cancer might have underestimated gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity because the related assessments have rarely been reported (particularly, a full evaluation of the significance of the correlations between high-resolution CT findings and the lung pathology)[12].

For the molecular mechanisms of the toxicity of gemcitabine, the exact pathogenesis of lung injury is not known yet. Gemcitabine has structural and metabolic similarities to cytosine arabinoside (1-b-arabinofuranosylcytosine, Ara-C), thus presents approximately the same patterns of the pulmonary toxicities as Ara-C due to the damage to the capillary endothelial cells resulting in pulmonary edema[5]. Besides, it seems that gemcitabine could induce the release of proinflammatory cytokines causing deregulation of tissue repair[15]. Specifically, in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, enhanced expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and tumor growth factor (TGF)-beta induces proliferation and transformation of the extracellular matrix in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis[16], which is similar to the mechanism of the bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis[10].

For our patient, what is different from the previous reports is that the patient received the gemcitabine by intravesical instillation. The instillation was maintained in the body for a short time as an ablative effect and then released completely, which indicated that the absorption was deemed to be quite a small amount. The safety of gemcitabine is tested in different instillation schemes, drug concentrations, and administered volumes. Its safety profile is excellent, with good tolerability and minimal toxicity up to 2000 mg per 50 mL for 2-h instillations[8]. In our case, the intravesical instillation cycle was given every 2 wk for a total of 30 cycles, which indicated the potential and probable cumulative effect of gemcitabine intravesical instillation systemically. As far as intravesically instilled gemcitabine is concerned, this is the first report of associated pulmonary toxicity. For the gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity by the endovascular route, the cumulative effect was uncertain because the median cycle of occurrence for the systemically used gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity was usually an acute phase, during the second cycle or 48 d[5], with a range of approximately 1 to 14 cycles, after initiation of gemcitabine[1]. This correlated with the physiopathological mechanism of the inflammatory reaction of the alveolar capillary wall: Cytokine-mediated abnormal permeability of its membrane as an immediate or acute rapid process with the histologic manifestations of interstitial and intra-alveolar proteinaceous edema[5,17]. For this acute toxicity, a hyperpermeability of the pulmonary capillaries known as capillary leak syndrome, it was reported to be reversible and dose-limiting with the maximal tolerant dosage in the pig model at a concentration at 320 µg/mL[7]. In some scatted cases, delayed changes including interstitial pneumonitis or pulmonary fibrosis were reported[1,5,18,19]. It should be noted that the lung perfusion of gemcitabine after 90 d in rats induced a significant increase in pulmonary fibrosis, compared with the intravenous group regardless of the dose[6]. As for the intravesical instillation, although complete exclusion might be expected after a short time of withholding and then complete release, minimal chemotherapy leaks might be responsible for the lung injury in this patient. As in one previous study, minimal chemotherapy leaks of cytostatic drugs were detected in the systemic circulation after isolated lung perfusion for pulmonary metastasis with no hepatic or renal toxicity[20].

In the presence of normal spirometry parameters, many severe and diffuse pulmonary injuries may occur with chemotherapy[21]. Due to the relatively low incidence and various manifestations of gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity, it is difficult to definitively predict the patients who may develop pulmonary toxicity. Besides the possible cumulative effect, the potential risk factors for this patient might be the main contributing reasons for the intravesical-instilled gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity. Based on an analysis of patient characteristics from published case series or clinical trials, the risk factors include age of more than 65 years; male gender[2]; previous or pulmonary concomitant disease, thoracic irradiation, or association with another drug that may damage the respiratory system[5]; performance status; and pretreatment forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) ≤ 2 L[22]. In the current case, our patient had the following predisposing factors: He is a male older than 65 years of age with a 40 pack-year smoking history and concomitant pulmonary emphysema and bullae. Combined with the postulated pathogenesis of the gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicities as deregulation of the lung tissue repair and the increased proliferation and transformation of the extracellular matrix, the predisposing factors that could imbalance the lung tissue repair and increase the release of PDGFR and TGF-beta, may accentuate or aggravate the pulmonary toxicity of gemcitabine, which is in accordance with the previous findings on the predisposing risk factors.

In our case, the radiologic and pathological changes were in accordance with the diagnosis of organizing pneumonitis. Nevertheless, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia or a hypersensitivity pneumonitis–like pattern was found to be the predominant radiologic manifestation in gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicities[12]. In one case of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, the specimens obtained by video-assisted thoracic surgery revealed a random distribution of granulomas or organizing tissue that was not relevant to the respiratory bronchiole, corresponding to the high resolution computed tomography (HRCT)-determined centrilobular nodules identified as a hypersensitivity pneumonitis pattern. In two cases confirmed by transbronchial lung biopsy, exudative inflammation found within the alveolar area correlated to the HRCT-determined centrilobular nodules[12]. Regarding the histologic examinations for gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity, widespread type-2 pneumocyte hyperplasia together with hyaline membrane formation, areas of fibrous thickening of alveolar walls, organizing exudate within alveoli, and patchy alveolar hemorrhage sometimes occurred. However, histologically, it is still difficult to differentiate from other unrecognized extrinsic causes or other potential etiologies[23]. Thus, the history and serologic, microbiologic, and microscopic examinations should be taken into consideration for the definite diagnosis, especially when the symptoms are nonspecific and rapidly progressive.

In summary, health care professionals should monitor for gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicities after gemcitabine chemotherapy, especially in patients with high-risk factors, even in the usage of intravesical instillation. With regard to the cumulative dosage and effect, and the possible delayed changes, numerous and consecutive cycles should be followed and close monitoring by chest CT should be performed.

| 1. | Belknap SM, Kuzel TM, Yarnold PR, Slimack N, Lyons EA, Raisch DW, Bennett CL. Clinical features and correlates of gemcitabine-associated lung injury: findings from the RADAR project. Cancer. 2006;106:2051-2057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gupta N, Ahmed I, Steinberg H, Patel D, Nissel-Horowitz S, Mehrotra B. Gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity: case report and review of the literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25:96-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stathopoulos GP. Cisplatin: process and future. J BUON. 2013;18:564-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Toschi L, Finocchiaro G, Bartolini S, Gioia V, Cappuzzo F. Role of gemcitabine in cancer therapy. Future Oncol. 2005;1:7-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Barlési F, Villani P, Doddoli C, Gimenez C, Kleisbauer JP. Gemcitabine-induced severe pulmonary toxicity. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2004;18:85-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Van Putte BP, Hendriks JM, Romijn S, De Greef K, Van Schil PE. Toxicity and efficacy of isolated lung perfusion with gemcitabine in a rat model of pulmonary metastases. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;54:129-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pagès PB, Derangere V, Bouchot O, Magnin G, Charon-Barra C, Lokiec F, Ghiringhelli F, Bernard A. Acute and delayed toxicity of gemcitabine administered during isolated lung perfusion: a preclinical dose-escalation study in pigs. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;48:228-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hendricksen K, Witjes JA. Intravesical gemcitabine: an update of clinical results. Curr Opin Urol. 2006;16:361-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dalbagni G, Russo P, Sheinfeld J, Mazumdar M, Tong W, Rabbani F, Donat MS, Herr HW, Sogani P, dePalma D, Bajorin D. Phase I trial of intravesical gemcitabine in bacillus Calmette-Guérin-refractory transitional-cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3193-3198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fenocchio E, Depetris I, Campanella D, Garetto L, Schianca FC, Galizia D, Grignani G, Aglietta M, Leone F. Successful treatment of gemcitabine-induced acute interstitial pneumonia with imatinib mesylate: a case report. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Friedberg JW, Neuberg D, Kim H, Miyata S, McCauley M, Fisher DC, Takvorian T, Canellos GP. Gemcitabine added to doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vinblastine for the treatment of de novo Hodgkin disease: unacceptable acute pulmonary toxicity. Cancer. 2003;98:978-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tamura M, Saraya T, Fujiwara M, Hiraoka S, Yokoyama T, Yano K, Ishii H, Furuse J, Goya T, Takizawa H, Goto H. High-resolution computed tomography findings for patients with drug-induced pulmonary toxicity, with special reference to hypersensitivity pneumonitis-like patterns in gemcitabine-induced cases. Oncologist. 2013;18:454-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Roychowdhury DF, Cassidy CA, Peterson P, Arning M. A report on serious pulmonary toxicity associated with gemcitabine-based therapy. Invest New Drugs. 2002;20:311-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vahid B, Marik PE. Pulmonary complications of novel antineoplastic agents for solid tumors. Chest. 2008;133:528-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ciotti R, Belotti G, Facchi E, Cantù A, D'Amico A, Gatti C. Sudden cardio-pulmonary toxicity following a single infusion of gemcitabine. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sabria-Trias J, Bonnaud F, Sioniac M. [Severe interstitial pneumonitis related to Gemcitabine]. Rev Mal Respir. 2002;19:645-647. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kouroussis C, Mavroudis D, Kakolyris S, Voloudaki A, Kalbakis K, Souglakos J, Agelaki S, Malas K, Bozionelou V, Georgoulias V. High incidence of pulmonary toxicity of weekly docetaxel and gemcitabine in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: results of a dose-finding study. Lung Cancer. 2004;44:363-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Van Schil PE, Hendriks JM, van Putte BP, Stockman BA, Lauwers PR, Ten Broecke PW, Grootenboers MJ, Schramel FM. Isolated lung perfusion and related techniques for the treatment of pulmonary metastases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:487-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Leo F, Pelosi G, Sonzogni A, Chilosi M, Bonomo G, Spaggiari L. Structural lung damage after chemotherapy fact or fiction? Lung Cancer. 2010;67:306-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Arrieta O, Gallardo-Rincón D, Villarreal-Garza C, Michel RM, Astorga-Ramos AM, Martínez-Barrera L, de la Garza J. High frequency of radiation pneumonitis in patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with concurrent radiotherapy and gemcitabine after induction with gemcitabine and carboplatin. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:845-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Koide T, Saraya T, Nakamoto K, Nakajima A, Ishii H, Fujiwara M, Shibata H, Oka T, Goya T, Goto H. [A case of imatinib mesylate-induced pneumonitis based on the detection of epithelioid granulomas by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery biopsy in a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2011;49:465-471. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Galvão FH, Pestana JO, Capelozzi VL. Fatal gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity in metastatic gallbladder adenocarcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;65:607-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Feinstein MB, DeSouza SA, Moreira AL, Stover DE, Heelan RT, Iyriboz TA, Taur Y, Travis WD. A comparison of the pathological, clinical and radiographical, features of cryptogenic organising pneumonia, acute fibrinous and organising pneumonia and granulomatous organising pneumonia. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68:441-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Avtanski D, Dinç T S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ