Published online Oct 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4544

Peer-review started: April 15, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Revised: August 4, 2020

Accepted: August 20, 2020

Article in press: August 20, 2020

Published online: October 6, 2020

Processing time: 165 Days and 22.8 Hours

Globally, although the jellyfish population has increased in recent years, ocular jellyfish stings remain an uncommon ophthalmic emergency, and have been rarely reported. According to a few previous reports, ocular jellyfish stings may cause anterior segment disorders, and most of these injuries were self-limited and spontaneously resolved within 24 to 48 h.

A brother and sister both presented with severe fundus complications several years after ocular jellyfish stings and both had prolonged blurred vision. To our knowledge, such fundus lesions induced by jellyfish stings have not been reported previously.

The fundus status of patients following ocular jellyfish stings should be carefully monitored in cases of irreversible ocular damage.

Core Tip: Ocular jellyfish stings may cause severe fundus complications and result in prolonged blurred vision, which is different from previous reports on jellyfish injuries.

- Citation: Zheng XY, Cheng DJ, Lian LH, Zhang RT, Yu XY. Severe fundus lesions induced by ocular jellyfish stings: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(19): 4544-4549

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i19/4544.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4544

Jellyfish are distributed in oceans and costal zones worldwide. They consist of a bell-shaped body and several tentacles which contain nematocysts. The nematocysts contain venom which is toxic to humans[1]. The venom can cause potential systemic symptoms including gastrointestinal, muscular, cardiac, neurological and allergic manifestations when the toxins enter the general circulation[2]. In addition, the venom is also toxic to ocular tissue and can cause conjunctiva injection, punctate epithelial keratitis, corneal stromal edema, endothelial cell swelling, mild anterior chamber flare, atypical severe iritis and increased intraocular pressure[3-6]. However, ocular fundus disease caused by jellyfish stings has not yet been reported.

Here we report two patients who developed severe fundus complications including optic atrophy, retinal vascular occlusion, thinning of the retina and scar formation in the macular area after ocular jellyfish stings.

A 13-year-old boy accompanied by his father and sister, presented to the Ophthalmology Department in August 2019, complaining of conjunctival injection and blurred vision in his right eye for more than a year.

He had suffered a jellyfish sting in the right eye about two years ago, and experienced severe pain in his right eye and decreased visual acuity after the accident. After a short-term treatment (irrigation of the conjunctiva with normal saline, eye drops and oral drugs), the pain disappeared, but his best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) did not recover. His parents were unaware of his injury; thus, he did not receive any further treatment, and his vision gradually decreased.

His elder sister also coincidentally had a jellyfish sting in the left eye four years ago, and her visual acuity in the left eye decreased one year later, and no other etiology except the jellyfish sting was confirmed after many detailed examinations in a number of hospitals.

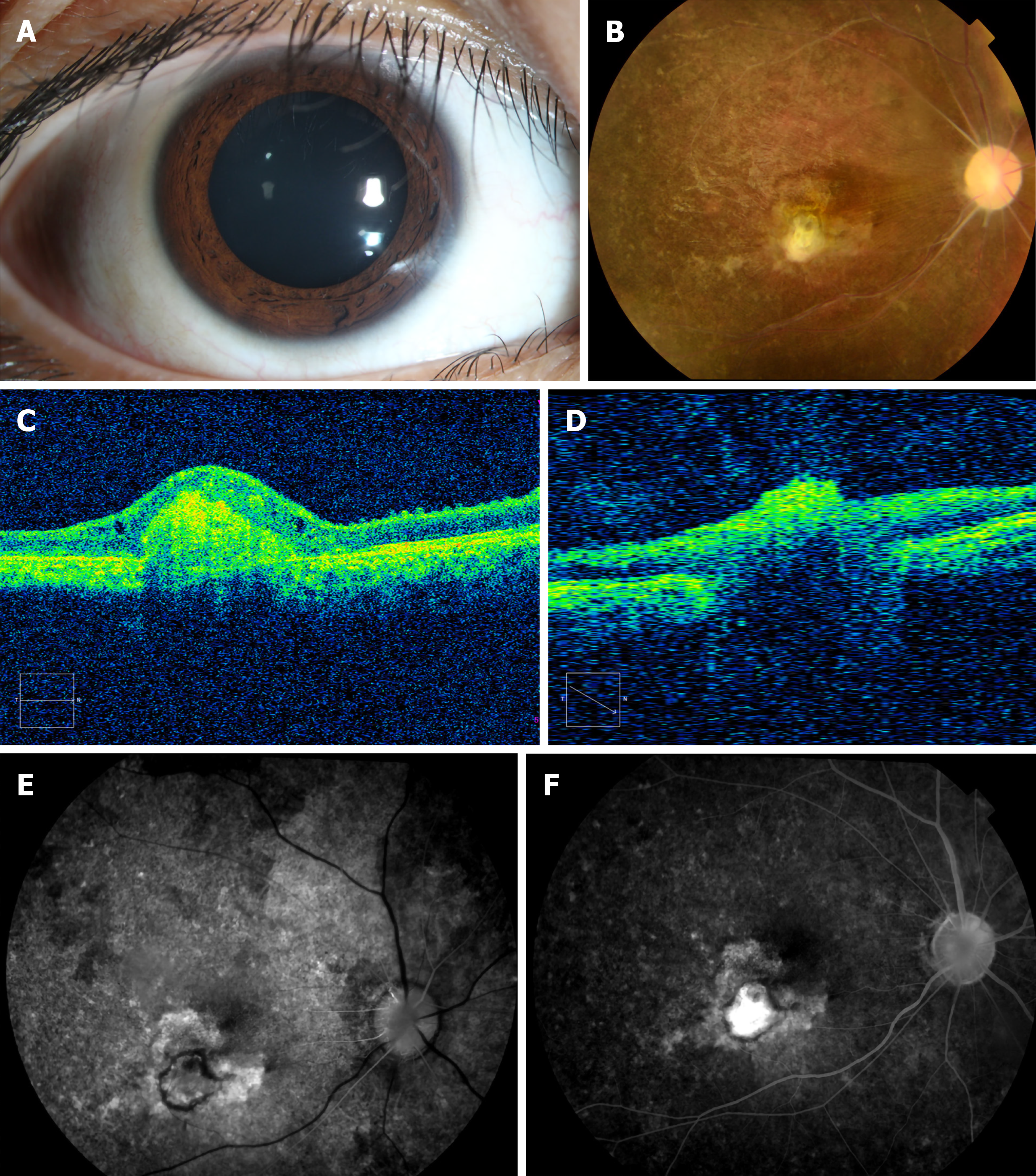

On examination, his BCVA was hand movement in the right eye and 1.0 in the left eye, and intraocular pressures were normal. The low vision in his right eye came as shock to his father, as he was unaware of the jellyfish sting, which also attracted our attention. Further examinations of his right eye were carried out to make a definitive diagnosis. Slit-lamp examination of his right eye confirmed that the anterior segment was normal except that the conjunctiva was 1+ injected and the pupil measured 3 mm with a relative afferent pupil defect (Figure 1A). Unexpectedly, the posterior segment examination of his right eye revealed diffuse optic disc pallor, partial retinal vascular occlusion, pigmentation of the retina and a gray-white lesion (scar) inferior to the fovea (Figure 1B). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the left eye showed diffuse thinning of the whole retinal layer, OCT B-scans passing through the gray-white lesion showed an elevated hyperreflective signal with disruption of retinal pigment epithelium integrity and mild outer retinal edema. When passing through the optic disk, OCT scans demonstrated a severely reduced peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer compared with the left eye (Figure 1C and D). Fundus fluorescein angiography examinations of the right eye revealed that the retinal arterial blood filling time and venous blood return time were prolonged, the gray-white lesion was characterized by hyperfluorescence in the early phase, fluorescein staining in the late phase, and stippled areas of hyperfluorescence indicating retinal pigment epithelium dysfunction (Figure 1E and F).

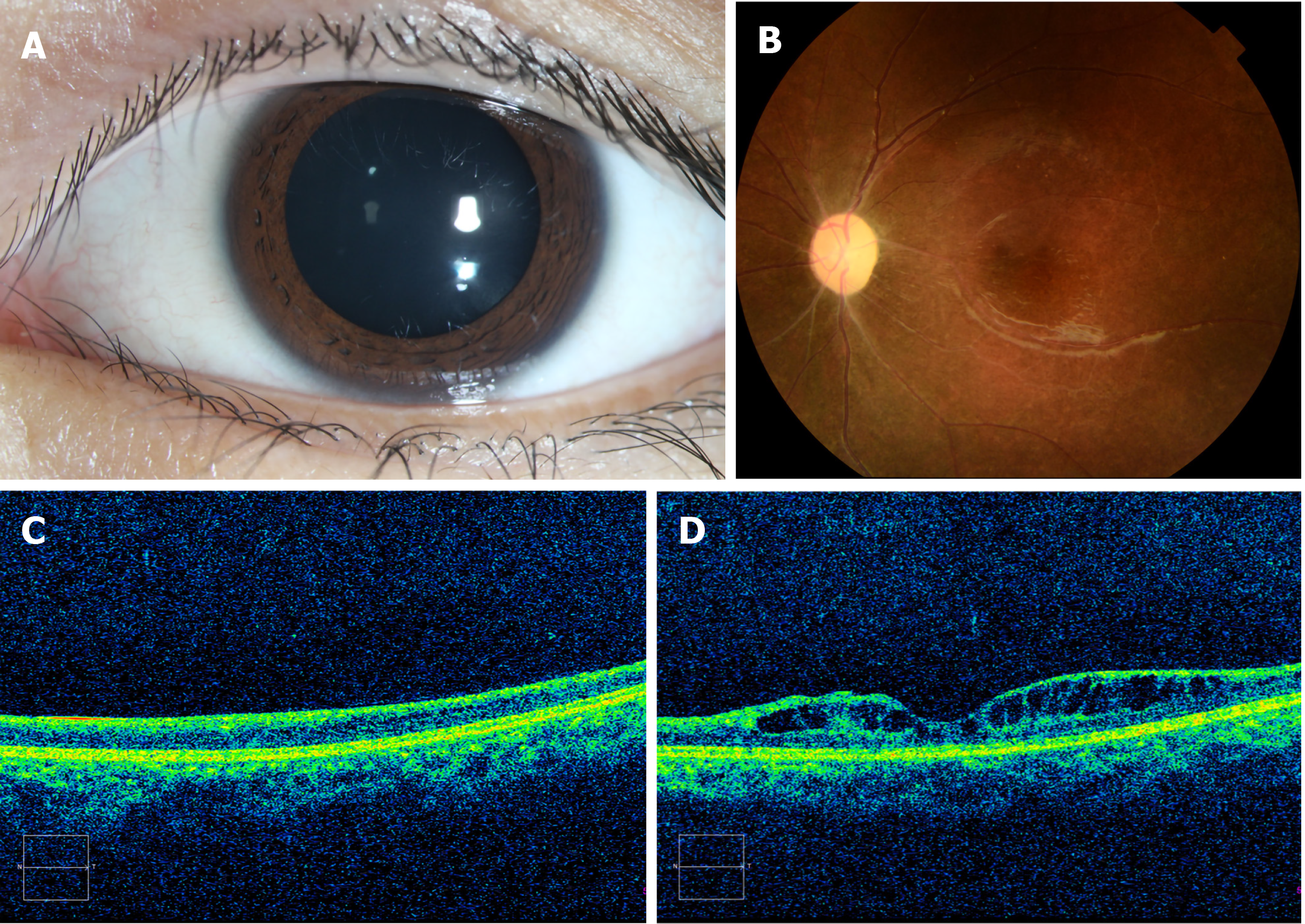

In order to obtain a further understanding of the disease, we carried out a detailed examination of his sister with her consent, and found that the anterior segment was normal except for a relative afferent pupil defect. Therefore, we performed a posterior segment examination of the girl’s left eye, which also showed optic disc pallor, partial retinal vascular occlusion, and pigmentation in the peripheral retina (Figure 2A and B). OCT images also confirmed diffuse thinning of the whole retinal layer with cystoid macular edema (Figure 2C and D), and BCVA in her left eye was finger count. The brother and sister, who both suffered from ocular jellyfish stings, showed similar presentations.

In order to determine the etiology, further examinations were performed. He was tested for toxoplasmosis, other agents, rubella, cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex infections, which showed that cytomegalovirus IgG was 12.416 U/mL, rubella IgG was 49.182 IU/mL, and herpes simplex virus-I/II IgG was 22.423 U/mL. Blood analysis of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid for Leber hereditary optic neuropathy was also performed, and no mutations of G3460A, G11778A, and T14484C were detected in the mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid analyses.

As the brother and sister had similar ocular lesions, we suggested that genetic testing should be carried out to exclude genetic diseases, but their father refused. He stated that three years ago when his daughter’s vision decreased after a jellyfish sting in the left eye, in order to exclude genetic diseases, all other members of the family (the girl’s parents and grandparents, and two sisters and a brother) had undergone ocular examinations in a local hospital, which were verified to be normal.

An orbit magnetic resonance imaging scan revealed that the optic nerve in the right eye was thinner than that in the left eye, and there were no obvious brain abnormalities.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was optic atrophy, partial retinal vascular occlusion, pigmentation of the retina and a macular scar, which were thought to have been induced by ocular jellyfish stings.

Treatment included improvement of the ocular blood circulation and protection of the optic nerve for one week.

After one week of treatment, he was discharged from hospital without obvious improvement in his condition (the possible poor prognosis had been explained to the family before treatment). The patient subsequently received the same treatment for 6 mo, and during a total follow-up period of 12 mo, there was still no improvement in his eyesight or fundus characteristics.

According to previous reports, jellyfish stings can induce ocular manifestations, such as diseases of the eyelid, conjunctiva, cornea and anterior chamber with severe pain, photophobia and lacrimation[3-5,7]. Most injuries were self-limited and spontaneously resolved within 24 to 48 h[8]. However, the potential for long-term sequelae exists. As reported by Glasser et al[6], complications infrequently occur after ocular jellyfish stings, and can include iritis, chronic unilateral glaucoma, mydriasis and loss of accommodation. We are not aware of previous reports of ocular jellyfish stings resulting in ocular fundus diseases. The cases in our report developed severe fundus complications including optic atrophy, retinal vascular occlusion, thinning of the retina and scar formation in the macular area, which resulted in persistent visual impairment. To our knowledge, this report is the first to describe these reactions following ocular jellyfish stings. However, the detailed pathological mechanism remains unclear and requires further investigation.

According to reports, the nematocysts eject their threads with an approximate force of 40000 g to strike the skin or the cornea[9]. Mao et al[8] suggested that stings due to this weak energy level were incapable of penetrating the full thickness of the skin and cornea. Therefore, most patients recovered without permanent sequelae. Burnett et al[5] concluded that this energy enables the threads to penetrate the upper dermis, which diffuse into the circulation and produce several syndromes. However, these conclusions need to be confirmed. In our cases, both patients suffered from ocular jellyfish stings and then developed ocular fundus diseases, unlike most patients who were reported to recover without permanent sequelae. This may be due to venom penetrating the intraocular area. As reported, the diameter of a jellyfish bell ranges from 2 to 30 cm, and the severity and energy of the sting is correlated with the size of the creature, with small jellyfish (5-7 cm diameter bell) causing less severe stings than larger jellyfish (> 15 cm diameter bell)[10], which may indicate that the jellyfish which stung the boy was large and the venom may have penetrated the intraocular area and resulted in his poor outcome.

Contact with a jellyfish tentacle causes millions of nematocysts to pierce the skin and inject venom. The venom is a mixture of toxic and antigenic polypeptides and enzymes[11], and evenomation can lead to harmful consequences and even death[10,12]. Choudhary et al[12] identified around 150 proteins in jellyfish venom, and considered that some of the components play an important role in the hematological, cytotoxic and allergenic effects of the venom. In addition, it has been reported that the venom can induce vasospasm, ischemia and vasculitis which are likely to be caused by inflammatory mediators or vasoactive substances[11]. As reported, jellyfish stings can induce severe ischemia and gangrene and result in permanent disability if treatment is delayed, and several cases have been reported[11,13]. Similarly, if the venom is injected into the eyes, it is possible that this can cause retinal ischemia and even atrophy of retinal tissues as reported in this study.

Although it is possible that the ocular lesions were caused by genetic disorders, taking into consideration all the relevant factors (similar experiences, similar presentations, no related genetic diseases reported and so on), we believe that the ocular lesions were likely caused by jellyfish stings, and this inference is reasonable according to previous reports. Despite the evidence being insufficient, we believe that it still has some reference value for clinical diagnosis.

Therefore, we should attach importance to the development of ocular disease following jellyfish stings, as jellyfish venom may penetrate deep tissues under certain circumstances and cause severe fundus lesions (such as optic atrophy, partial retinal vascular occlusion, pigmentation of the retina and macular scarring) and result in prolonged blurred vision.

According to similar experiences and eye presentations, and based on related reports regarding the striking energy and toxic effects of jellyfish, it is believed that the ocular lesions in these cases were likely caused by jellyfish stings. In addition to ocular surface diseases, jellyfish stings in the eyes may also induce ocular fundus diseases which can cause severe fundus lesions and vision loss. Thus, the fundus status of these patients should be carefully monitored during a long follow-up period in cases of irreversible ocular damage even if they initially only have ocular surface diseases.

We are grateful to the patients and their parents for allowing us to report the cases.

| 1. | Cegolon L, Heymann WC, Lange JH, Mastrangelo G. Jellyfish stings and their management: a review. Mar Drugs. 2013;11:523-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tibballs J. Australian venomous jellyfish, envenomation syndromes, toxins and therapy. Toxicon. 2006;48:830-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sonmez B, Beden U, Yeter V, Erkan D. Jellyfish sting injury to the cornea. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2008;39:415-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wong SK, Matoba A. Jellyfish sting of the cornea. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;100:739-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Burnett JW, Calton GJ, Burnett HW. Jellyfish envenomation syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:100-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Glasser DB, Noell MJ, Burnett JW, Kathuria SS, Rodrigues MM. Ocular jellyfish stings. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1414-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Winkel KD, Hawdon GM, Ashby K, Ozanne-Smith J. Eye injury after jellyfish sting in temperate Australia. Wilderness Environ Med. 2002;13:203-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mao C, Hsu CC, Chen KT. Ocular Jellyfish Stings: Report of 2 Cases and Literature Review. Wilderness Environ Med. 2016;27:421-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Holstein T, Tardent P. An ultrahigh-speed analysis of exocytosis: nematocyst discharge. Science. 1984;223:830-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Auerbach PS, Gupta D, Van Hoesen K, Zavala A. Dermatological Progression of a Probable Box Jellyfish Sting. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019;30:310-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lo AH, Chan YC, Law Y, Cheng SW. Successful treatment of jellyfish sting-induced severe digital ischemia with intravenous iloprost infusion. J Vasc Surg Cases. 2016;2:31-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Choudhary I, Hwang DH, Lee H, Yoon WD, Chae J, Han CH, Yum S, Kang C, Kim E. Proteomic Analysis of Novel Components of Nemopilema nomurai Jellyfish Venom: Deciphering the Mode of Action. Toxins (Basel). 2019;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Binnetoglu FK, Kizildag B, Topaloglu N, Kasapcopur O. Severe digital necrosis in a 4-year-old boy: primary Raynaud's or jellyfish sting. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Vagholkar K S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Ma YJ